Abstract

Patient: Female, 16

Final Diagnosis: Castleman’s Disease

Symptoms: Chest pain • cough non-productive

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Castleman’s disease, or angiofollicular lymphoid hyperplasia, is a rare disorder and can be easily misdiagnosed as lymphoma, neoplasm, or infection. The diagnosis is challenging due to the nonspecific signs and symptoms as well as the rarity of the disease. We present an unusual case of a young girl presenting with an enlarging pulmonary mass that was believed to be infectious in origin.

Case Report:

A 16-year-old Native American female from Arizona initially presented with occasional non-productive cough and chest pain. Imaging revealed a 3-cm left upper lobe lobulated mass. This mass was thought to be due to coccidioidomycosis and was treated with fluconazole. Follow-up imaging demonstrated growth of the mass to 4.8 cm. The patient underwent a left video-assisted thoracoscopic left upper lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadenectomy. Histopathological examination revealed Castleman’s disease.

Conclusions:

Pulmonary masses in young patients can be easily misdiagnosed as infections or cancer. We present the case of a 16-year-old female misdiagnosed as having a fungal infection of the lung, which was later revealed to be Castleman’s disease of the left upper lobe.

MeSH Keywords: Coccidioidomycosis, Giant Lymph Node Hyperplasia

Background

Castleman’s disease is a rare atypical lymphoproliferative disorder of uncertain etiology [1]. Diagnosis can be challenging and treatment of unicentric Castleman’s disease often involves surgical resection. There is limited data in the literature regarding pulmonary Castleman’s disease in young patients who are otherwise healthy. We present a rare case of pulmonary Castleman’s disease in a 16-year-old patient, which was initially thought to be due to Coccidioidomycosis.

Case Report

A 16-year-old Native American female from Arizona initially presented with occasional non-productive cough and chest pain. Imaging in 2010 revealed a 3-cm left upper lobe lobulated mass. This mass was thought to be due to coccidioidomycosis and the patient was on chronic fluconazole therapy for 3 years. The details of the follow-up visits are unknown because she was referred top the thoracic surgical team after follow-up imaging revealed growth of the mass despite antifungal therapy.

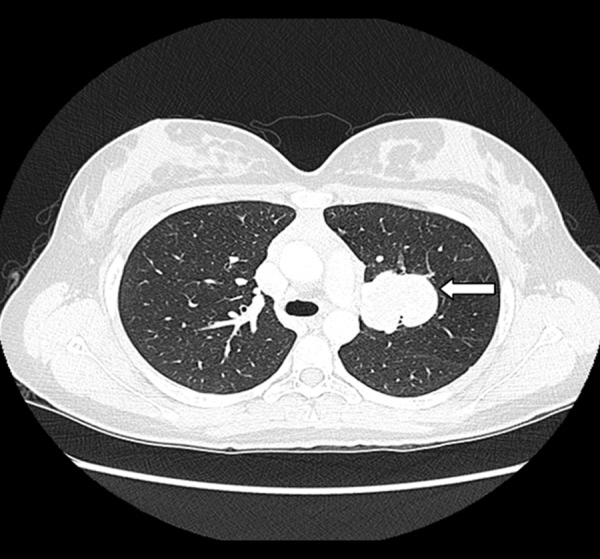

CT imaging (Figure 1) demonstrated growth of the left upper lobe mass up to 4.8 cm. Flexible bronchoscopy did not reveal any abnormalities. There was no evidence of infection. The patient underwent a left video-assisted thoracoscopic left upper lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadenectomy.

Figure 1.

CT scan showing left upper lobe mass.

Intraoperatively, significant fibrotic changes in the left lung were noted. The mass (Figure 2), which was located in the central portion of the left upper lobe, appeared fleshy. A frozen section of the mass was obtained and was negative for carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Lung mass after excision.

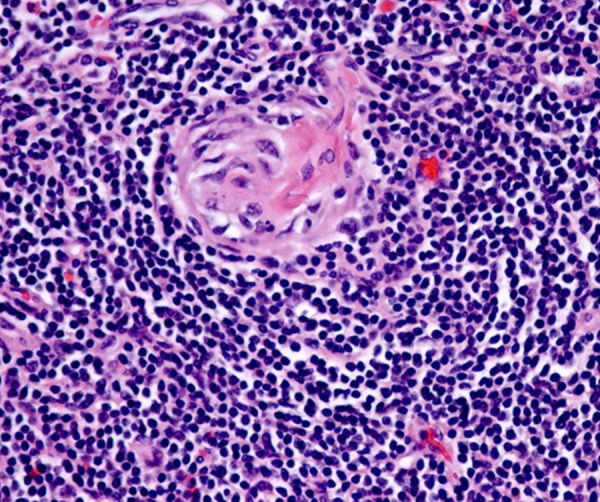

Histopathological examination revealed granuloma-like change, mainly centered in germinal centers. These germinal centers also demonstrated follicular hyperplasia and mantle zone onion skinning (Figure 3), reminiscent of Castleman’s disease. Fungal and AFB stains were negative, as were culture results.

Figure 3.

Histopathology slide showing follicular hyperplasia and mantle zone onion skinning.

Discussion

Castleman’s disease is a rare atypical lymphoproliferative disorder that can be easily misdiagnosed. It can occur wherever lymph nodes are present, most commonly the mediastinum [2]. Benjamin Castleman initially described this disease in mediastinal lymph nodes in 1956 [3]. Presently, there is no definitive cause of Castleman’s disease; however, HIV, HHV8, and IL6 are all thought to play a role in lymphoid hyperplasia and possibly the pathogenesis of Castleman’s disease [4,5].

The signs and symptoms of Castleman’s disease are nonspecific and include fever, night sweats, and lymphadenopathy. Many diseases such as infections and cancers can present with these symptoms, including Coccidiomycosis; thus, Castleman’s disease can mimic many different possible diagnoses. Also characterized as a pseudolymphoma, Castleman’s disease can be described as unicentric and multicentric [6], with both types have 3 histologic subtypes: hyaline vascular, plasma cell, and mixed. Unicentric Castleman’s disease is usually of the hyaline vascular type and has less symptoms and better prognosis than the multicentric disease, which is usually of the plasma cell or mixed type [7,8].

The unicentric form is seen in approximately 90% of cases [9]. The median age of diagnosis is 35, which makes this case of a 16-year-old female quite interesting [10]. In our patient, the left upper lobe mass was initially thought to be due to a coccidiomycosis infection. A key learning point is that the diagnosis should always be challenged, especially if treatment with the appropriate antifungal does not result in resolution or significant size decrease in the mass. The patient had been treated with antifungal treatment for at least 3 years with no resolution in the mass and ultimately increased growth.

Pulmonary Castleman’s disease is rarely reported in the literature and is even rarer in a young patient. The best treatment option for the unicentric Castleman’s disease is complete surgical resection. Complete resection of the involved node is curative and has been considered the gold standard approach for the treatment of unicentric Castleman’s disease. Disease-free survival rates at 3 and 5 years were 90% and 81%, respectively. Complete resection was the only significant predictor of mortality [11]. Recurrences have been reported in cases related to incomplete initial resection or missed lymph nodes [12]. Use of rituximab has been described in unresectable tumors or in neo-adjuvant treatment prior to a surgical resection to shrink the tumor [13].

Conclusions

In conclusion, pulmonary masses of Castleman’s disease in young patients can be easily misdiagnosed as infections or cancer. Diagnosis can be challenging and very difficult when limited tissue is obtained, mainly because of the lack of pathognomonic features on most imaging studies. Surgical resection is often diagnostic and therapeutic. We present the case of a 16-year-old female misdiagnosed as having a fungal infection of the lung, which was later revealed to be Castleman’s disease of the left upper lobe.

References:

- 1.Adrian YY, Becker TS, Rice DH. Giant lymph node hyperplasia of the head and neck (Castleman’s disease): a report of five cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 1995;113(4):462–66. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadir A, Colak N, Koktener A. Isolated intrapulmonary Castleman’s disease: A case report, review of the literature. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.13-00253. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castleman B, Towne VW. Case records of the Massachusetts general hospital: case 32–1984. N Engl J Med. 1954;311:388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fajgenbaum DC, van Rhee F, Nabel CS. HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Blood. 2014;123:2924–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-545087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower M, Stebbing J. Exploiting interleukin 6 in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):910–12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70333-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flendrig J. Benign giant lymphoma: clinicopathologic correlation study. The Year Book of Cancer. 1970:296–99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ota H, Kawai H, Matsuo T. Unicentric Castleman’s disease arising from an intrapulmonary lymph node. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:289089. doi: 10.1155/2013/289089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frizzera G, Peterson BA, Bayrd ED, Goldman A. A systemic lymphoproliferative disorder with morphologic features of Castleman’s disease: clinical findings and clinicopathologic correlations in 15 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(9):1202–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.9.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JR, Skarin AT. Clinical mimics of lymphoma. Oncologist. 2004;9(4):406–16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-4-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dispenzieri A. Castleman disease. Cancer Treat Res. 2008;142:293–30. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73744-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talat N, Belgaumkar AP, Schulte KM. Surgery in Castleman’s disease: a systematic review of 404 published cases. Ann Surg. 2012;255:677–84. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318249dcdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowne WB, Lewis JJ, Filippa DA. The management of unicentric and multicentric Castleman’s disease: a report of 16 cases and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1999;85(3):706–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<706::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estephan FF, Elghetany MT, Berry M, Jones DV., Jr Complete remission with anti-CD20 therapy for unicentric, non-HIV-associated, hyaline-vascular type, Castleman’s disease. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]