Abstract

Bacteria are perfect vessels for targeted cancer therapy. Conventional chemotherapy is limited by passive diffusion, and systemic administration causes severe side effects. Bacteria can overcome these obstacles by delivering therapeutic proteins specifically to tumors. Bacteria have been modified to produce proteins that directly kill cells, induce apoptosis via signaling pathways, and stimulate the immune system. These three modes of bacterial treatment have all been shown to reduce tumor growth in animal models. Bacteria have also been designed to convert nontoxic prodrugs to active therapeutic compounds. The ease of genetic manipulation enables creation of arrays of bacteria that release many new protein drugs. This versatility will allow targeting of multiple cancer pathways and will establish a platform for individualized cancer medicine.

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. While conventional therapies have reduced cancer mortality, their efficacy often falls short in preventing tumor recurrence. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are limited in their success due to the development of drug resistance, inadequate tumor penetration and poor tumor specificity [1–3]. The use of live bacteria offers a solution to these limitations.

Bacteria can be engineered to be cancerspecific therapy vectors. Tumor microenvironments provide a safe harbor for bacteria in the human body. Clearance by the immune system is limited and growth is promoted by abundant nutrients [4,5]. Bacteria specifically colonize tumor niches in ratios of 10,000:1 compared with healthy tissue [6–8]. Bacteria also have flagella that allow them to actively move in tumors and penetrate to regions far from vasculature [9]. These inherent features are essential for bacterial cancer targeting. Bacterial tumor specificity and active motility can treat regions that are currently untreatable with passively diffusing chemotherapy [10,11]. Administration of attenuated bacterial strains to tumor-bearing mice has resulted in tumor regression, tumor shrinkage and even complete tumor eradication [12–15]. By creating an infection in tumors, bacteria immunosensitize the host to the cancer, attract the immune system and induce tumor clearance [16,17]. In clinical trials, bacteria were found to localize in tumors, but did not reduce tumor volume [18]. Overcoming this limited effectiveness in humans is a major goal of current research on bacterial-based therapies.

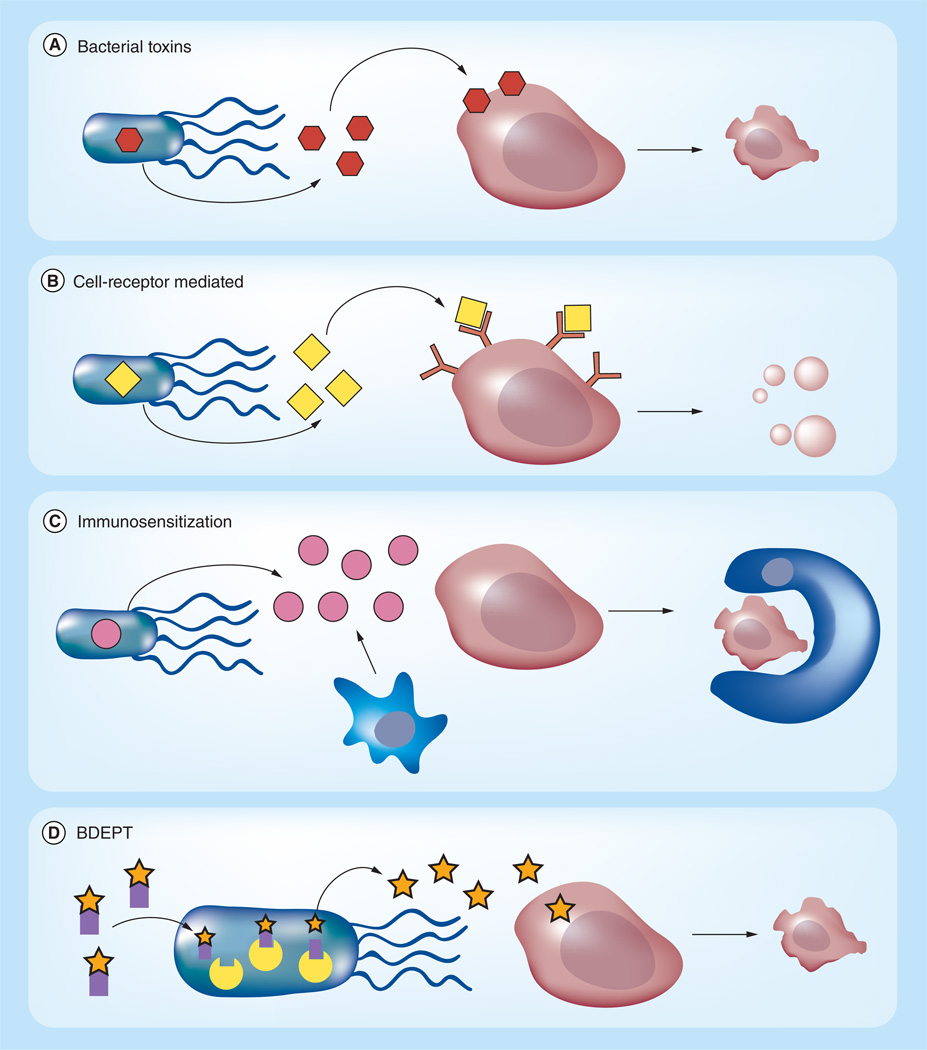

Bacteria can be armed with therapeutic drugs to increase the cytotoxic effect. Having a small haploid genome makes genetic manipulation feasible. Genetically engineered bacteria can express and release cytotoxic proteins (Figure 1), such as bacterial toxins [19–22], immunoregulatory proteins [23–26] and apoptosis-inducing factors [27,28]. Bacteria can also be engineered to carry enzymes for the conversion of nontoxic prodrugs into cytotoxic drugs [29–32]. Tumor-specific accumulation allows for higher therapeutic doses without toxic side effects. In addition, bacteria are metabolically active after colonization, which results in continuous drug production in tumors [33]. External triggers have been used to regulate transcription in order to restrict production to within tumors and minimalize side effects [21,27]. Temporal control of gene transcription can be achieved with inducible promoters that are sensitive to radiation [34–36] or external molecules [21,37].

Figure 1. Modes of bacterial protein delivery.

Bacteria can produce and release protein drugs (A–C) and convert prodrugs into active compounds (D). (A) Bacterial toxins (orange hexagons) can be expressed to kill cancer cells (blue). (B) Bacteria can produce eukaryotic proteins (yellow diamonds) that interact with receptors on the surface of cancer cells. These proteins often target cell signaling pathways that induce apoptosis. (C) Bacteria can also produce cytokines (pink circles) that attract granulocytes and dendritic cells (red amorphous). These cells use dead tumor tissue for antigen uptake and induce the innate and adaptive immune systems to kill cancer cells, often by phagocytosis. (D) Bacteria can express enzymatic catalysts (yellow) that convert nontoxic prodrugs (orange stars with purple squares) into toxic therapeutics (orange stars).

BDEPT: Bacterial-directed enzyme prodrug therapy.

For color images please see online www.future-science.com/doi/full/10.4155/TDE.14.113

Bacterial therapy has the potential to become a new and important tool for treating cancer. The combination of inherent bacterial features with gene technology allows for the use of multiple protein drugs and specialized approaches to different tumor types.

Bacteria as delivery vectors

Bacterial cancer therapy is not new. One of the pioneers of bacterial treatment of cancer was William B. Coley, who, in 1890, discovered that serious bacterial infections had a remedial effect on tumor patients. Using a vaccine derived from Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens, called Coley’s toxin, he treated advanced tumors and even induced full disease regression [38,39]. A recent study determined that the 10-year survival rate after treatment with Coley’s toxin was similar to that of a cancer patient treated in 1983 with conventional non-radiotherapeutic cancer therapy [40]. With the arrival of radiotherapy, bacterial cancer treatment was no longer implemented in clinics. Over the last 20 years, bacterial cancer targeting has been gaining scientific interest due to its potential to increase treatment efficacy with minimal toxicity [41].

Several bacterial genera have been shown to accumulate in tumor tissue. These bacteria can be divided in two groups based on their oxygen metabolism: obligate anaerobes (Bifidobacterium and Clostridium) and facultative anaerobes (Salmonella, Escherichia and Listeria) [22,42–45].

Due to lack of anaerobic tissues in the human body, anaerobic strains only grow in the necrotic regions of tumors [46]. When administered to tumorbearing mice, both Clostridium and Bifidobacterium are only found in tumors, with virtually no bacteria in healthy tissue [47]. Several differences can be noted between these two strains. Bifidobacterium is non-toxic and a natural part of human intestinal flora. It can be administered intravenously (iv.) without inducing side effects, as it is not recognized by the immune system [47,48]. Clostridium is a human pathogen that cannot be injected iv. without toxicity. To overcome host toxicity, its spores can be administered without inducing toxic effects [49]. Due to innate production of lethal toxins that spread systemically, Clostridium has been attenuated for therapeutic purposes [49]. These attenuated bacteria remain oncolytic after deletion of the toxin genes, indicating that the toxins are not solely responsible for tumor inhibition [49]. Combination with chemotherapy and radiotherapy has been shown to increase tumor reduction in mice [49,50].

For optimal tumor treatment, a homogeneous spread of bacteria throughout tumors is necessary. Bifidobacterium proliferates in localized high-density clusters with little spread, limiting its therapeutic effect. Clostridium, however, spreads more homogeneously throughout tumors in smaller colonies, resulting in better treatment [49]. A drawback of anaerobic bacteria is their inability to target and kill oxygenated tissue close to vasculature [13,50]. Similarly, these bacteria cannot be used to target small metastasis that do not contain anoxic tissue.

Facultative anaerobic bacteria, such as Salmonella, Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes can colonize well oxygenated regions as well as necrotic regions farther from blood vessels [9]. The ability to grow independent of oxygen enables these bacteria to target both primary tumors and metastases [8,51–53]. Both Salmonella and Listeria have been shown to accumulate in tissues in ratios of 10,000:1 compared with healthy tissue [7, 8]. For E. coli, ratios up to a 100,000:1 compared with spleen and liver tissue have been observed [54]. Salmonella strains have been shown to colonize metastasis as small as five cell layers thick [55]. A downside of E. coli and Salmonella is that these organisms preferentially localize to necrotic regions [54]. To overcome this, highly motile bacteria would penetrate further into tumors, which would result in more homogeneous treatment [9].

Five key mechanisms are known to promote preferential bacterial accumulation in tumors. Intravenous administration of bacteria causes an inflammation response and production of TNF and other cytokines [56]. This induction increases blood flow and entraps bacteria in tumors [7,56]. Increasing the TNF response has been shown to increase bacterial accumulation and spread in tumors, indicating that controlling the initial inflammation can increase colonization [57]. Chemotaxis attracts bacteria to quiescent, necrotic and anaerobic regions [4,58]. Deletion of chemotaxis signal transduction inhibits tumor colonization, showing that chemotaxis is essential for the tumor localization [58]. In addition, several receptors, such as the aspartate, serine, and ribose/galactose receptors, guide bacteria to specific tumor microenvironments [58]. Bacteria proliferate in these beneficial microenvironments [4], where they are also protected from clearance by the immune system [5].

The immune system is one of the main mechanisms that ensures tumor specificity. After iv. injection, attenuated Salmonella are cleared from the bloodstream after six hours in non-human primates [59]. After seven days, non-clearance organs are free of bacteria and none are present in any organ after 41 days [59]. Tumors are privileged environments that avoid detection by the immune system, and which allow bacteria to colonize. Tumors evade the adaptive immune system by impairing antigen presentation [60]. One mechanism of evasion is reduction in level or complete loss of major histocompatibility complex-1 (MHC-1) which is necessary for antigen presentation [60]. A second mechanism is production of immunosuppressive proteins such as TGF-β, VEGF, prostaglandins and IL −10 [60].

Most bacterial strains are pathogenic and the presence of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and other virulence factors can induce a toxic immune response. To be used for clinical purposes, most tumor-targeting strains have been attenuated by modifying their LPS or making them auxotrophic [8,61–62]. Auxotrophs, such as leucine-arginine-deficient or purine-deficient strains, are dependent on external sources for these essential components and rely on the release of these nutrients from necrotic and disintegrating tumor tissue [63]. These mutations restrict bacteria to tumors and help clear them from healthy tissue [63]. Modifying LPS has been shown to decrease the TNF response in mice 10,000-fold and considerably reduce the risk of septic shock [59]. The unfortunate consequence of this modification is reduction in tumor colonization [57].

Tumor-colonizing bacteria have an endogenous oncolytic effect that results in successful tumor treatment in animal models. Bacteria in tumors sensitize the immune system, resulting in tumor clearance [16,64–66]. Intracellular invasion of bacteria does not have a direct toxic effect on cancer cells even though it is cytotoxic to macrophages [64]. Bacteria attract the innate immune system, e.g., macrophages, granulocytes, to tumors after two days and lymphocytes (B/T-cells) after six days [64]. Both B and T cells increase bacterial tumor inhibition and pretreatment with vaccines against bacteria increases the tumor-shrinking response [16,64–66]. Bacterial therapy in mice and dogs has resulted in reduction of tumor volume, prevention of metastasis formation, and complete remission [12,15,51,67–69].

Toll-like receptors (TLR) expressed by cancer cells are activated by bacteria. TLR4 is activated by Gram-negative LPS, and TLR2 is predominantly activated by Gram-positive bacteria [70]. TLR5 reacts to flagellin, a component of bacterial flagella [70]. Several studies have shown that activation of TLR by bacterial infection increases tumor proliferation and progression [71–73]. This counterproductive mechanism suggests that adaptation of bacterial LPS to limit TLR activation will increase the efficacy of bacterial cancer treatment.

Initial positive results with bacterial tumor targeting resulted in a Phase-I clinical trial [18]. In this trial, VNP20009 was safely administered to patients [12,18,62]. This strain has a partial deletion of the msbB gene, modifying its LPS, and a partial deletion of the purI gene, making the bacteria dependent on external sources of purines. Although bacterial accumulation was shown after iv. injection, no tumor regression was measured [18]. To increase the efficacy of bacterial antitumor therapy, bacteria can be armed with proteins to increase their oncolytic potential.

Bacterial delivery of proteins

After tumor colonization, bacteria remain metabolically active and continue to produce and release proteins. Using their inherent metabolic pathways, bacteria can be generated that secrete therapeutic proteins. To be successful for tumor treatment, therapeutic proteins need to be easily expressed, secreted and toxic to cancer cells [21]. Long-term release of a selected therapeutic compound will maintain a lethal concentration in tumors. For optimal production of a therapeutic protein, multiple factors need to be taken into account. Smaller proteins have higher production rates [74]. Substituting rare codons for more common ones increases translation rates [75]. Bacteria can produce high concentrations of proteins, but this can have negative effects on bacterial metabolism and growth. Non-native proteins can be toxic to bacteria by blocking the production of proteins or even by directly causing bacterial death.

After transcription and translation, proteins needs to be released into the extracellular space. This can be achieved by adding secretion sequences to the protein coding sequence or by triggered lysis. Bacteria have several secretion mechanisms that can be used for the release of recombinant proteins. Salmonella, for example, uses a Type 3 Secretion System (T3SS) to deliver proteins directly into the cytoplasm of host cells [76,77]. For this secretion pathway, a chaperone and an N-terminal peptide tag are required [78]. There are no conserved amino acid sequences between the N-terminal secretion tags of different substrates for a given secretion system, but using the N-terminal tags of known secreted proteins, sequences have been designed that increase the chance of secretion [78,79]. The concentration of the released protein depends on the protein and the specific secretion pathway. A second strategy is induced bacterial lysis. Expression of phage lysis genes has been shown to generate pores in bacterial cell walls [80]. Two examples of phage lysis systems are lysis gene E [81,82] and the lysis genes of Salmonella phage iEPS5 [37]. Placing these genes under the control of an inducible promoter allows for release at a controlled time [37]. Induced lysis releases the bacterial content into the tumor microenvironment [37]. While this mechanism releases all produced protein into the tumor, it kills the bacteria and cannot be used for a long-term treatment. In addition, if an external compound is used to trigger lysis, this compound is limited by passive diffusion and may not reach the bacteria.

Regulating protein expression

For bacterial delivery of cytotoxic compounds, control over gene expression is critical to avoid delivery to healthy tissue. After injection, bacteria are cleared out of the blood and healthy organs [7,59,63,83]. Constitutive gene expression during this initial colonization period would distribute drugs systemically and cause damaging side effects. Gene expression can be controlled using either externally inducible promoters or microenvironment-sensing promoters.

Inducible promoters can be activated by chemical compounds or by γ-irradiation. Several bacterial induction systems have been identified that respond to chemical inducers that are non-toxic and not produced by humans. These inducer molecules are necessary to prevent inadvertent expression. l-arabinose induces the pBAD system, a tightly regulated promoter that can turn on or off in minutes [84]. Both intraperitoneal and iv. administration of l-arabinose to bacterially colonized mice has been shown to induce gene expression in tumors [85,86]. IPTG is a cell-permeable allolactose that induces the lac operon [87]. Addition of IPTG to the drinking water of mice has been shown to induce gene expression [87]. The use of chemical compounds for induction is dependent, however, on passive diffusion and is subject to the same limitations as chemotherapy.

A second approach is the use of γ-irradiation to trigger gene expression. γ-irradiation has several advantages: it can easily penetrate tissue, it is not limited by diffusion, and treatment can be localized to cancerous regions [27,34]. A common way to construct a radiation-sensitive trigger is with the endogenous recA promoter [27]. When radiation causes double-stand breaks in the bacterial genome, the RecA protein and its promoter are activated [88]. This promoter has been used to control multiple therapeutic proteins, including TNFα and TRAIL [27,36]. A weakness of this system is high basal gene expression [27,36]. To overcome this limitation and prevent protein leakage in an uninduced state, an extra Cheo box has been incorporated into the promoter [35]. This modification reduced basal expression by 30%, rendering the promoter more specific to radiation-induced activation [35].

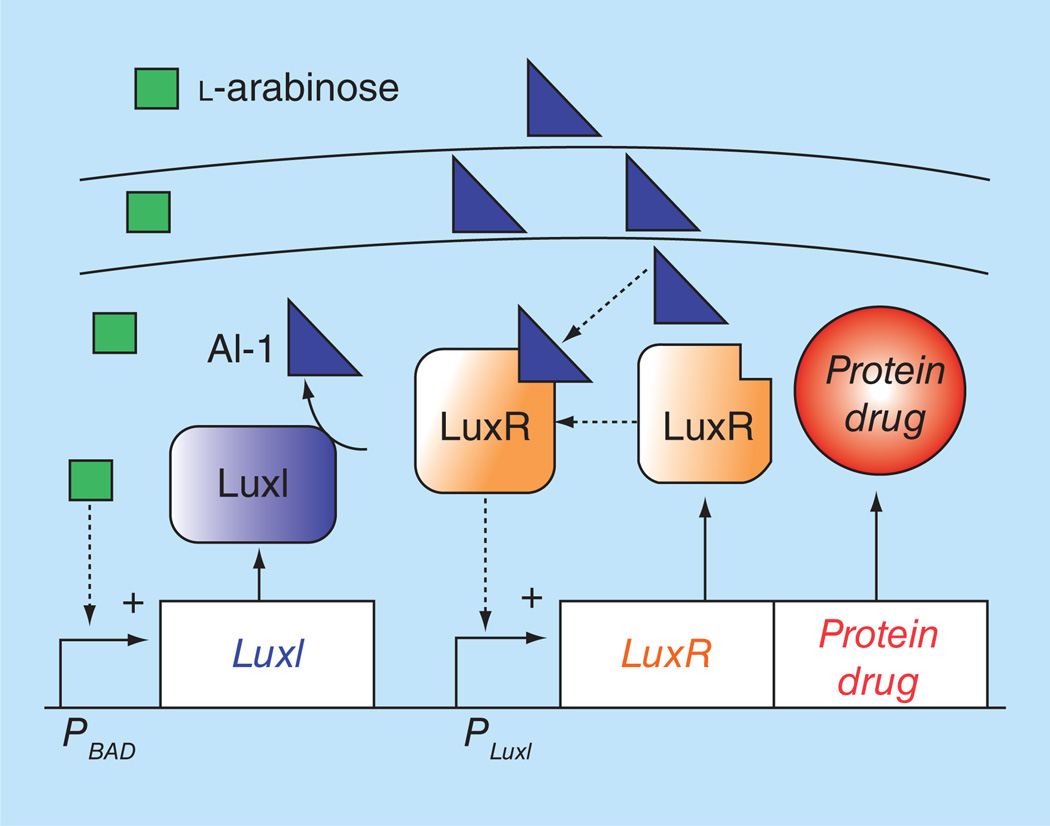

Another strategy to overcome the limitation of inducible promoters is amplification of the inducing signal. To induce transcription, an external trigger must reach a threshold concentration, but, like chemotherapy, it availability is reduced by passive diffusion. To amplify an inducing signal, our laboratory engineered a system to enable communication between individual Salmonella (Figure 2) [33]. This system is based on the quorum sensing gene circuit in Vibrio fischeri [89]. It contains two genes: luxI and luxR. LuxI catalyzes the formation of the autoinducer AI-1 (acylhomoserine lactone), which can freely cross bacterial membranes [89]. When a threshold of AI-1 is reached, LuxR is activated and binds the PluxI promoter, inducing transcription [89]. In the created system, transcription of luxI was placed under control of the PBAD promoter. Arabinose addition induces luxI transcription, which results in increased AI-1 levels and activation of PluxI [33]. Diffusion of AI-1 away from activated bacteria in turn activates PluxI in surrounding bacteria [33]. We have shown that this system increases bacterial protein production 350-fold in tumor tissue in vitro [33].

Figure 2. Amplification system based on cell-cell communication.

The system is based on the quorum-sensing machinery of Vibrio fischeri. Communication is initiated by addition of an external molecule, l-arabinose (green squares), which triggers production of an intercellular autoinducer molecule, AI-1 (blue triangles). In this system, transcription of luxI is controlled by the PBAD promoter. Arabinose addition induces luxI transcription, which enzymatically produces AI-1. The rise in AI-1 concentration activates PluxI which produces LuxR (orange boxes) and the desired protein drug (orange circle). Diffusion of AI-1 into inactivated bacteria activates PluxI thus communicating the activation with surrounding bacteria.

For color images please see online www.future-science.com/doi/full/10.4155/TDE.14.113

Another alternative to externally inducible promoters is microenvironment-sensing promoters. Bacteria can sense their microenvironment and adapt their metabolism by regulating gene transcription. These environmentally triggered gene promoters can be adapted for use in the tumor microenvironment. For example, hypoxia-sensitive promoters containing fumarate and nitrate reduction elements (nirB, pepT) can be used to confine the expression of therapeutic proteins to anoxic regions of tumors [90,91]. A drawback of these promoters is that they are limited to treating large anoxic tumors.

Different proteins, different targets

An effective protein drug is one that quickly kills cancer cells at low doses. Compounds that kill quickly are often too toxic for systemic therapy, but specific release by bacteria in tumors would eliminate this toxicity. Currently, therapeutic proteins fall in one of three categories based on their mode of action: cytotoxic compounds, such as bacterial toxins; proteins that target cancer pathways and induce cell death; and immunoregulatory proteins that activate the immune system.

Bacterial toxins

Bacterial toxins can be effective anticancer therapeutics because they indiscriminately kill cells. Local release of toxins in tumors would specifically kill cancer cells. Their broad potency makes them effective against many cell types that are resistant to current therapies, e.g., triple negative breast cancer [21]. Tumor specificity is essential for use of bacterial toxins. Systemic use would induce severe side effects. Examples of toxins that have been explored are cytolysin A (ClyA) and Staphylococcus aureus α-hemolysin (SAH). These pore-forming toxins have been shown to kill cancer cells and reduce tumor volume [19–21]. ClyA is endogenously expressed by several Escherichia and Salmonella strains and induces cellular lysis of infected cells. Both E. coli and Salmonella can readily produce and secrete this toxin. To increase the cytotoxic effect, E. coli were modified to constitutively express ClyA [19]. In multiple tumor models, these engineered organisms inhibit tumor growth and block formation of lung metastasis [19,92]

SAH is an extremely potent toxin. It induces oncosis in cancer cells in as fast as 6 min [21]. Both E. coli and Salmonella express and secrete the active form of this toxin [20,21]. SAH acts by forming heptameric pores in mammalian cells [93], after being produced and secreted as a monomer [94]. During secretion, an N-terminal secretion signal is cleaved, which enables association of the individual units and formation of pores [21,94–95]. When injected into mice, SAH-secreting bacteria reduced viable tissue in tumors to 9% of the original volume [20]. Because this toxin diffuses through tissue, its treatment area is 64-fold greater than an effect localized to bacterial colonies [20].

Pore-forming toxins have the potential to be effective cancer therapeutics, but their lack of specificity for cancer cells requires strict control of expression. Their general mode of action enables use against many different cancer types, including those resistant to current therapies [21]. However, systemic expression could be dangerous. Controlling expression of these toxins with a tightly regulated system, which has low basal expression, would ensure safety of the approach.

A more specific cancer drug is azurin. This redox protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa is selectively taken up by cancer cells but spares healthy tissue [96]. Azurin interferes with electron transfer during denitrification [97]. In cancer cells, it stabilizes p53, leads to increased expression of Bax, and induces apoptosis [98–100]. Azurin can also bind to Eph receptor tyrosine kinases, which are upregulated in cancer [101]. Interaction with azurin blocks binding to the endogenous ligands of kinase receptor EphB, inhibiting cell signaling and cancer growth [101]. E. coli Nissle 1917, carrying mature azurin fused to the pelB leader sequence, reduces tumor proliferation in B16 mouse melanoma and 4T1 breast tumors [22]. The delivery of azurin prevents the formation of pulmonary metastasis compared with treatment with control bacteria [22]. It reduces tumor growth, but does not lead to tumor shrinkage [22].

Targeting eukaryotic cell signaling

Bacterial vectors have also been used to target cell signaling pathways. These pathways are essential in maintaining cancer cell proliferation, and cell membrane receptors are well-known cancer targets. Several bacterial strains expressing proapoptotic proteins, such as Noxa [37], TRAIL [27,91] and FAS ligand (FASL) [28], have been shown to kill cells and reduce tumor volume. Noxa is a proapoptotic protein downstream of p53 that triggers apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction [102–104]. The mitochondrial targeting domain of Noxa induces mitochondrial calcium leakage into the cytosol and causes subsequent necrosis [105]. Fusion of the mitochondrial targeting domain of Noxa to a cell penetrating peptide and expression in an attenuated Salmonella strain suppresses tumor formation and induces necrosis, when injected into mice with CT-26 colorectal cancer xenografts [37].

TRAIL is a cytokine that induces apoptosis by binding to death receptors, which are expressed more frequently on cancer cells [106]. Although TRAIL has potential to be a potent anticancer drug, it is illsuited for systemic delivery due to its short half-life [107]. Bacterial delivery can overcome this obstacle by production directly in tumors. Binding of TRAIL to death receptors 4/5 activates caspase 8-dependent apoptosis [108]. To use TRAIL as a therapeutic protein, our laboratory created an expression vector by placing TRAIL under the control of the radiation-induced promoter PrecA. Irradiating Salmonella, transformed with this construct, induced release of TRAIL. In mice, TRAIL had a synergistic effect on reducing tumor growth: the combination of TRAIL and radiation decreased the doubling time almost twofold [27]. Two doses of bacteria and radiation caused tumor volume to decrease [27]. Another group placed TRAIL under control of a hypoxia-induced nirB promoter. Salmonella with this construct caused a small suppression of melanoma, but no suppression of TRAIL-resistant RM-1 prostate cancer [91].

A third potent anticancer protein is FASL. FASL cannot be administered systemically because it induces apoptosis and lethal liver injury [109,110]. Expression of recombinant FASL in Salmonella increased its effect. These bacteria suppressed D2F2 and CT-26 tumors by 59 and 82%, respectively, and decreased the volume of D2F2 lung metastasis by 34% [28].

Another treatment modality that can target cell receptors specifically is monoclonal antibodies that block ligand binding. The discovery and purification of single domain antibodies enables bacteria to synthesize functional antibodies. Bacteria can improve antibody-based cancer therapies by delivering higher concentrations specifically to tumors. Expression and secretion of monoclonal antibodies has been shown in Clostridium novyi [111]. The coding sequence of a single domain antibody targeting HIF-1α was fused to an eglA N-terminal secretion sequence [111]. Clostridium, carrying this expression vector, produced and secreted a functional form of the HIF-1α antibody [111].

Triggering the immune system

The immune system plays an important, though complex, role in bacterial therapy. Throughout disease progression, tumors develop multiple ways to escape the immune system, including the loss of MHC class I molecules on their cell surfaces and the production of TGF and IL-10, which block immune responses [6,60]. Initial bacterial accumulation is aided by the immuneprivileged environment in tumors. Over time, however, a bacterial infection increases tumor antigenicity, induces an innate immune response and can result in tumor clearance [6,54,60,64,112]. This innate immune response can be increased by the release of specific cytokines by bacteria. Interleukins IL-2 and IL-18 stimulate lymphocyte differentiation and enhance the cytolytic function of T-cells and natural killer cells, promoting an antitumor immune response [113–117]. Systemic administration of these interleukins causes severe side effects, such as myocardial (IL-18) and renal (IL-2) dysfunction [118,119]. The release of IL-18 by Salmonella in BALB/c mice with CT-26 colon carcinoma induced leukocyte infiltration and reduced tumor progression [25]. Treating mice that have B16F10 xenograft tumors with IL-2-secreting Salmonella decreased tumor proliferation and vascularity, and increased tissue necrosis [26]. This increased necrosis was caused by a T-cell-specific antitumor mechanism, because it was not observed in nude mice that lack T-cells [26].

Two other immune triggers that have been delivered by bacteria are the chemokine CCL21 and LIGHT [23,24]. Both LIGHT and CCL21 stimulate the migration of dendritic, T, B and natural killer cells and have antiangiogenic properties [23,24]. When administered to tumor-bearing mice, bacteria that secrete these compounds increase levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10, which attracted more T-cells and induced immune clearance of tumors [23,24]. In these mice, tumor proliferation and metastasis formation were decreased.

Bacteria-mediated enzyme prodrug therapy

Using bacteria to activate prodrugs has the potential to significantly decrease side effects from treatment. Bacterial-directed enzyme prodrug therapy uses bacterial metabolism to convert nontoxic chemical compounds into cytotoxic drugs. Compared with the direct delivery of drugs, this strategy magnifies the effect of the delivered protein; one delivered enzyme can activate many prodrug molecules. Several strategies have been attempted in Clostridium, E. coli and Salmonella. Expression of nitroreductase, from Haemophilus influenza, in Clostridium converts the monofunctional DNA-alkylating agent CB1954 to a more toxic difunctional form [120,121]. Repeated cycles with this bacterial strain, interchanged with antibiotic treatments, resulted in suppressed growth of HCT116 human colon carcinoma tumors in mice [30]. Using a more potent nitroreductase, identified in Neisseria meningitides, cured 25% of colon carcinoma tumors in mice [122].

Another prodrug therapy is based on the enzyme cytosine deaminase (CDase). It converts 5-fuorocytosine into the commonly used cancer drug, 5-fuorouracil. Salmonella expressing E. coli CDase has been shown to convert 5-FC to 5-FU in colon tumors in mice and inhibit tumor growth [31]. These CDaseexpressing bacteria were tested in a small clinical trial with three patients. In this trial, Salmonella-CD stabilized tumors, but did not induce tumor regression [123]. The intratumoral injections given in these studies did not reach the maximum tolerated dose [123]. Increasing the dosage to obtain higher colonization rates might have led to tumor shrinkage.

The endogenous metabolic enzymes of bacteria can also be used to convert prodrugs. In E. coli and Salmonella, the enzyme purine nucleoside phosphorylase converts nontoxic 6-methylpurine 2’-deoxyriboside (6MePdR) into the potent antitumor drug 6-methyl-purine (6MeP) [32]. In mice with B16F10 melanoma tumors, combined administration of Salmonella-purine nucleoside phosphorylase and 6MePdR significantly decreased tumor progression [32].

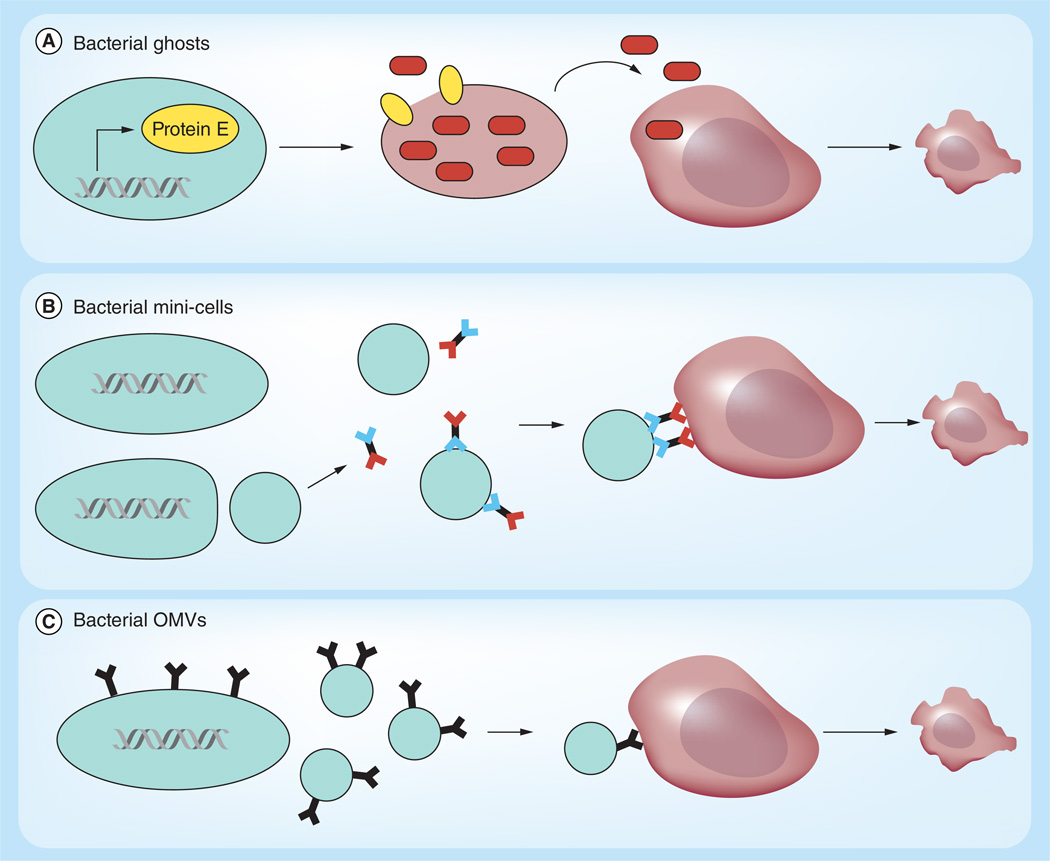

Bacterial membrane vesicles

An alternate method to deliver therapeutic drugs uses bacterial membranes as vehicles (Figure 3). Three distinct uses of bacterial membranes are bacterial ghosts, minicells and outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). Bacterial ghosts [124] are made from the envelopes of Gram-negative bacteria, after removal of their cytoplasmic content. Bacterial ghosts are produced by controlled expression of lysis gene E from bacterio-phage φX 174 [125]. This lysis gene oligomerizes into a transmembrane tunnel that spans the inner and outer membrane [126]. After the tunnel forms, the bacterial cytoplasm is released into the environment, while the periplasm remains associated with the bacterial shell [82]. Bacterial ghosts were originally designed for vaccine delivery [124]. They stimulate specific T-cells and are taken up by antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages [127]. Bacterial ghosts have also been used for drug delivery. Ghosts derived from Mannheimia haemolytica have been loaded with doxorubicin and used to treat human colon carcinoma cells [128]. The cancer cells absorbed the ghosts and a slow release of doxorubicin was observed over 8 days [128]. Doxorubicin delivery by ghosts was more effective than freely administered doxorubicin [128]. While the use of bacterial ghosts can overcome the pathogenicity associated with live bacteria, bacterial ghosts do not have the cancer-specific targeting abilities of live bacteria [128]. They have to be applied intratumorally, and due to the lack of an active metabolism, must be administered repeatedly for long-term treatment. This route of administration has advantages and disadvantages. Direct intratumoral application is not possible for hard-to-reach tumors and cannot be used for highly dispersed metastatic disease. However, intratumoral application allows for higher doses to be applied and does not require clearance of bacterial components out of the body. Direct release into tumors produces a more potent therapy with less side effects compared with free drug administration.

Figure 3. Bacterial membrane vesicles.

(A) Bacterial ghosts are cell membrane shells that can be used to delivery toxic compounds to tumors. The membrane vesicle is created by controlled expression of a phage lysis gene (here lysis protein E; blue ovals). Induction of the lysis gene creates pores in the bacterial membrane and releases the cytoplasm. The remaining membrane vesicle is loaded with doxycycline (brown ovals) and administered locally to cancer cells, where the membrane releases the drug. (B) Salmonella with a minCDE-chromosomal deletion generate 400 nm bacterial minicells. Bicistronic antibodies that recognize bacterial membrane (blue) and mammalian cell membrane (red) target bacterial minicells to cancer cells. Via endocytosis, minicells are taken up by cancer cells and the drug cargo is released in the cell cytoplasm. (C) Bacterial OMVs are discharged from Gram-negative bacteria (20–250 nm). Affibodies, expressed on the bacterial membrane, are enriched in OMVs and target the vesicles to cancer cells. Endocytosis of OMVs leads to release of the vesicle content into the cancer cell cytoplasm which results in cell death. OMV: Outer membrane vesicle.

For color images please see online www.future-science.com/doi/full/10.4155/TDE.14.113

Bacterial minicells are vesicles that specifically target tumors. Minicells are generated from Salmonella with a minCDE-chromosomal deletion that derepresses the polar sites in cell fission [129]. This deletion results in anucleate cells that are 400 nm in diameter and have no capacity for cell division. To render minicells specific to cancer cells, bispecific antibodies are attached that target LPS on the minicell surface and a specific tumor receptor, such as EGFR [129]. When administered to cells, anti-EGFR minicells access the cytoplasm via EGFR-mediated endocytosis. Minicells can also inject protein drugs into cells via the Salmonella T3SS system [130]. Each minicell can contain as many as 10 million drug molecules, which are released into the cytoplasm after degradation [131]. When administered to mice with xenograft tumors, minicell delivery of doxycycline or paclitaxel reduces tumor volume equivalent to the systemic administration of free drugs at 2000–8000 times the concentration [131]. While the administration of minicells is well tolerated, higher doses of doxycycline are also found in the liver, spleen and lungs compared to systemic administration. Accumulation in these tissues is probably due to clearance of minicells by phagocytic immune cells [131]. Clinical trials with chemotherapeutic minicells are currently ongoing. Minicells have also been developed that contain siRNA that is targeted to cancer-specific pathways [129]. In contrast to the use of live bacteria, minicell therapy needs to be administered multiple times. In mice, this repeat administration does not appear to induce an immune response [132].

A smaller version of minicells are OMVs. These 20–250 nm diameter proteoliposomes are normally discharged from the membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [133]. OMVs can be targeted to tumors by expressing tumor-specific molecules on their exterior surface. One group of targeting molecules are Her-2 affibodies, which bind upregulated HER2 receptors on breast cancer cells [134]. To localize affibodies (or other targeting molecules) to OMV membranes, they are genetically fused to the C-terminus of ClyA, a bacterial hemolysin [133]. OMVs are generated from msbB mutants that produce nonreactive LPS, to avoid an immune response [134]. Her-2-targeted OMV delivery of siRNAs to breast cancer cells depleted target proteins. When applied to mice with xenograft tumors, OMVs containing Kinesin Spindle Protein siRNA significantly reduced tumor growth [134].

Conclusion

Bacterial cancer therapy has shown promising results suppressing and eradicating tumors in animal models. Merging the inherent cancer targeting capacities of bacteria with genetic engineering has resulted in creation of bacterial vectors that have delivered a diverse array of therapeutic proteins and drug compounds to cancer cells. The specificity of bacteria allows the use of compounds that are too toxic for systemic administration. The ease with which these organisms can be genetically altered facilitates the generation of bacterial vectors targeting an array of different proteins. Combining therapies with different therapeutic targets can inhibit multiple pathways at once and achieve synergistic effects.

Future perspective

Translating these findings into clinical therapies will require reduction of bacterial toxicity to avoid side effects and ensure safety. This pathogenicity, however, also increases bacterial tumor accumulation and sensitizes the immune system to tumors. This can be a major contributor to the bacterial oncolytic effect. A fine balance needs to be achieved between these two factors to create a potent, thoroughly safe therapy. Increasing the native toxicity of bacteria by arming them with therapeutic proteins has shown to increase the anticancer effects. However, these effects were often small. Screening multiple potential protein drugs to assess their production rates and their toxicity could identify new and more potent protein drugs. The cancer treatment potential of bacteria has already been established, but this potential remains to be streamlined into effective and safe clinical therapies.

Studies over the last 20 years have shown the promise of bacterial cancer therapy for treating tumors. Clinical trials with attenuated Salmonella have demonstrated that bacteria can be safely administered and can colonize human tumors. Delivering therapeutic proteins increases the potency of bacterial therapy. Using bacteria as delivery vectors enables the release of compounds that are too toxic to administer systemically and opens up an array of new therapeutic possibilities. Bacteria can also be used to overcome drug resistance. Bacterial localization in quiescent regions enables treatment of cells that are resistant to chemotherapy. Therapeutic proteins released by bacteria would affect cells indiscriminately and be effective against all regions in a tumor. Due to the ease of genetic manipulation, bacteria can express therapies against multiple targets. Targeting multiple pathways can overcome the evolution of neoplastic cells to more drug-resistant phenotypes. Specific targeting to metastatic sites enables therapeutic bacteria to be an effective modality that reduces and treats tumor spreading [15,135]. For clinical application of bacterial therapy, several focus points still have to be addressed. Future studies should focus on the discovery of new protein therapeutics that are easily produced and secreted by bacteria at high concentrations, and are lethal to cancer cells in these concentration.

Executive Summary.

Bacteria can produce and release bacterial toxins, immunoregulatory proteins and proapoptotic proteins specifically into tumors, reducing tumor growth and volume.

Bacteria can enzymatically convert nontoxic prodrugs into cytotoxic compounds, delivering high doses of these therapeutics specifically into tumors.

Bacterial membrane vesicles can be directed to cancer cells, where they are absorbed and release cancer drugs.

The production and release of bacterially delivered therapeutics can be temporally controlled to avoid side effects.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. R01CA188382) and the Belgian American Education Foundation.

Key term

- Immunosensitize

Tumors have several mechanisms to evade detection by the immune system. Bacterial accumulation in tumors creates an infection that attracts immune cells to tumors, overcoming the escape mechanisms of tumors

- Lipopolysaccharides

Lipopolysaccharides are lipids covalently bound to polysaccharides. These endotoxins are present in the exterior membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and induce a strong immune response

- Auxotrophs

Bacterium unable to produce a compound needed for survival and growth. Auxotrophic bacteria only grow in select environments where the specific compound is abundant. Auxotrophs are more attenuated than other strains and are used as therapeutics because they are readily cleared out of healthy tissue

- Quorum sensing

Mechanism in bacteria that uses signaling molecules to tune gene expression to population density. This can be used to trigger and maintain gene expression in entire bacterial populations. A quorum-sensing-based triggering system is activated when a threshold bacterial density is reached

- Bacterial ghosts

Expression of phage lysis protein E in Gram-negative bacteria forms a pore connecting the inner and outer membrane. This pore releases the bacterial cytoplasm and leaves a bacterial membrane shell that can be loaded with therapeutic compounds and proteins

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest;

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6(8):583–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.St Jean AT, Zhang M, Forbes NS. Bacterial therapies: completing the cancer treatment toolbox. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008;19(5):511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain RK. The next frontier of molecular medicine: delivery of therapeutics. Nat. Med. 1998;4(6):655–657. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasinskas RW, Forbes NS. Salmonella typhimurium specifically chemotax and proliferate in heterogeneous tumor tissue in vitro. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006;94(4):710–721. doi: 10.1002/bit.20883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sznol M, Lin SL, Bermudes D, Zheng LM, King I. Use of preferentially replicating bacteria for the treatment of cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105(8):1027–1030. doi: 10.1172/JCI9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Streilein JW. Unraveling immune privilege. Science. 1995;270(5239):1158–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forbes NS, Munn LL, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Sparse initial entrapment of systemically injected Salmonella typhimurium leads to heterogeneous accumulation within tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(17):5188–5193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quispe-Tintaya W, Chandra D, Jahangir A, et al. Nontoxic radioactive Listeria(at) is a highly effective therapy against metastatic pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(21):8668–8673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211287110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toley BJ, Forbes NS. Motility is critical for effective distribution and accumulation of bacteria in tumor tissue. Integr. Biol. 2012;4(2):165–176. doi: 10.1039/c2ib00091a. • Demonstrating the importance of motility in bacterial tumor-targeting.

- 10.Zhang M, Forbes NS. Trg-deficient Salmonella colonize quiescent tumor regions by exclusively penetrating or proliferating. J. Control Release. 2014;199:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganai S, Arenas RB, Sauer JP, Bentley B, Forbes NS. In tumors Salmonella migrate away from vasculature toward the transition zone and induce apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011;18(7):457–466. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo X, Li ZJ, Lin S, et al. Antitumor effect of VNP20009, an attenuated Salmonella, in murine tumor models. Oncol. Res. 2001;12(11–12):501–508. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agrawal N, Bettegowda C, Cheong I, et al. Bacteriolytic therapy can generate a potent immune response against experimental tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(42):15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406242101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao M, Yang M, Ma HY, et al. Targeted therapy with a Salmonella typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7647–7652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao M, Geller J, Ma H, Yang M, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Monotherapy with a tumor-targeting mutant of Salmonella typhimurium cures orthotopic metastatic mouse models of human prostate cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(24):10170–10174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703867104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CH, Wu CL, Tai YS, Shiau AL. Systemic administration of attenuated Salmonella choleraesuis in combination with cisplatin for cancer therapy. Mol. Ther. 2005;11(5):707–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CH, Hsieh JL, Wu CL, Hsu PY, Shiau AL. T cell augments the antitumor activity of tumor-targeting Salmonella. Appl. Microbio. Biotechnol. 2011;90(4):1381–1388. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Toso JF, Gill VJ, Hwu P, et al. Phase I study of the intravenous administration of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium to patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20(1):142–152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.142. •• First clinical trail for cancer-targeting Salmonella.

- 19.Jiang SN, Phan TX, Nam TK, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by a combination of escherichia coli-mediated cytolytic therapy and radiotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2010;18(3):635–642. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St Jean AT, Swofford CA, Brentzel ZJ, Forbes NS. Bacterial delivery of Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin causes tumor regression and necrosis in murine tumors. Mol. Ther. 2013;22(7):1266–1274. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swofford CA, St Jean AT, Panetli JT, Brentzel ZJ, Forbes NS. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus α-hemolysin as a protein drug that is secreted by anticancer bacteria and rapidly kills cancer cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013;111(6):1233–1245. doi: 10.1002/bit.25184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Xia L, Zhang X, Ding X, Yan F, Wu F. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 targets and restrains mouse B16 melanoma and 4T1 breast tumors through expression of azurin protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78(21):7603–7610. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01390-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loeffler M, Le’negrate G, Krajewska M, Reed JC. Attenuated Salmonella engineered to produce human cytokine LIGHT inhibit tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12879–12883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701959104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loeffler M, Le’negrate G, Krajewska M, Reed JC. Salmonella typhimurium engineered to produce CCL21 inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2009;58(5):769–775. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loeffler M, Le’negrate G, Krajewska M, Reed JC. IL-18-producing Salmonella inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15(12):787–794. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Ramadi BK, Fernandez-Cabezudo MJ, El-Hasasna H, Al-Salam S, Bashir G, Chouaib S. Potent anti-tumor activity of systemically-administered IL2-expressing Salmonella correlates with decreased angiogenesis and enhanced tumor apoptosis. Clin. Immunol. 2009;130(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganai S, Arenas RB, Forbes NS. Tumour-targeted delivery of TRAIL using Salmonella typhimurium enhances breast cancer survival in mice. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;101(10):1683–1691. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loeffler M, Le’negrate G, Krajewska M, Reed JC. Inhibition of tumor growth using Salmonella expressing Fas ligand. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(15):1113–1116. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theys J, Landuyt W, Nuyts S, et al. Specific targeting of cytosine deaminase to solid tumors by engineered Clostridium acetobutylicum. Cancer Gene Ther. 2001;8(4):294–297. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theys J, Pennington O, Dubois L, et al. Repeated cycles of Clostridium-directed enzyme prodrug therapy result in sustained antitumour effects in vivo. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;95(9):1212–1219. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King I, Bermudes D, Lin S, et al. Tumor-targeted Salmonella expressing cytosine deaminase as an anticancer agent. Human Gene Ther. 2002;13(10):1225–1233. doi: 10.1089/104303402320139005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen G, Tang B, Yang B, et al. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium, a natural tool for activation of prodrug 6MePdR and their combination therapy in murine melanoma model. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97(10):4393–4401. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai YM, Toley BJ, Swofford CA, Forbes NS. Construction of an inducible cell-communication system that amplifies Salmonella gene expression in tumor tissue. Biotechnol. Bioengin. 2013;110(6):1769–1781. doi: 10.1002/bit.24816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nuyts S, Theys J, Landuyt W, Van Mellaert L, Lambin P, Anne J. Increasing specificity of anti-tumor therapy: cytotoxic protein delivery by non-pathogenic clostridia under regulation of radio-induced promoters. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(2A):857–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuyts S, Van Mellaert L, Barbe S, et al. Insertion or deletion of the Cheo box modifies radiation inducibility of Clostridium promoters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67(10):4464–4470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4464-4470.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nuyts S, Van Mellaert L, Theys J, et al. Radio-responsive recA promoter significantly increases TNFalpha production in recombinant clostridia after 2 Gy irradiation. Gene Ther. 2001;8(15):1197–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong JH, Kim K, Lim D, et al. Anti-tumoral effect of the mitochondrial target domain of Noxa delivered by an engineered Salmonella typhimurium. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e80050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nauts HC, Swift WE, Coley BL. The treatment of malignant tumors by bacterial toxins as developed by the late William B. Coley, MD, reviewed in the light of modern research. Cancer Res. 1946;6(4):205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mccarthy EF. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop. J. 2006;26:154–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richardson MA, Ramirez T, Russell NC, Moye LA. Coley toxins immunotherapy: a retrospective review. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 1999;5(3):42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forbes NS. Engineering the perfect (bacterial) cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10(11):785–794. doi: 10.1038/nrc2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohwi Y, Imai K, Tamura Z, Hashimoto Y. Antitumor effect of Bifidobacterium infantis in mice. Gan. 1978;69(5):613–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malmgren RA, Flanigan CC. Localization of the vegetative form of Clostridium tetani in mouse tumor following intravenous spore administration. Cancer Res. 1955;15(7):473–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pawelek JM, Low KB, Bermudes D. Tumor-targeted Salmonella as a novel anticancer vector. Cancer Res. 1997;57(20):4537–4544. •• One of the first studies of Salmonella as a tumor-targeting therapy.

- 45.Kim SH, Castro F, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. High efficacy of a listeria-based vaccine against metastatic breast cancer reveals a dual mode of action. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5860–5866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambin P, Theys J, Landuyt W, et al. Colonisation of Clostridium in the body is restricted to hypoxic and necrotic areas of tumours. Anaerobe. 1998;4(4):183–188. doi: 10.1006/anae.1998.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kimura NT, Taniguchi S, Aoki K, Baba T. Selective localization and growth of Bifidobacterium bifidum in mouse tumors following intravenous administration. Cancer Res. 1980;40(6):2061–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Amano J, Kano Y, Taniguchi S. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for cancer gene therapy: Selective localization and growth in hypoxic tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7(2):269–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dang LH, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Combination bacteriolytic therapy for the treatment of experimental tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(26):15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251543698. • Comprehensive study of the efficiency of anaerobic bacteria as a tumor-therapy.

- 50.Bettegowda C, Dang LH, Abrams R, et al. Overcoming the hypoxic barrier to radiation therapy with anaerobic bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(25):15083–15088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036598100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayashi K, Zhao M, Yamauchi K, et al. Cancer metastasis directly eradicated by targeted therapy with a modified Salmonella typhimurium. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009;106(6):992–998. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayashi K, Zhao M, Yamauchi K, et al. Systemic targeting of primary bone tumor and lung metastasis of high-grade osteosarcoma in nude mice with a tumor-selective strain of Salmonella typhimurium. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(6):870–875. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.6.7891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu YA, Shabahang S, Timiryasova TM, et al. Visualization of tumors and metastases in live animals with bacteria and vaccinia virus encoding light-emitting proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22(3):313–320. doi: 10.1038/nbt937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Westphal K, Leschner S, Jablonska J, Loessner H, Weiss S. Containment of tumor-colonizing bacteria by host neutrophils. Cancer Res. 2008;68(8):2952–2960. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganai S, Arenas RB, Sauer JP, Bentley B, Forbes NS. Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium effectively targets breast cancer metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009;16:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Leschner S, Westphal K, Dietrich N, et al. Tumor invasion of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium is accompanied by strong hemorrhage promoted by TNF-alpha. PloS One. 2009;4:e6692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006692. • Key mechanism of inflammation and TNF induction by bacteria effect tumor colonization.

- 57.Zhang M, Swofford CA, Forbes NS. Lipid A controls the robustness of intratumoral accumulation of attenuated Salmonella in mice. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;135(3):647–657. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kasinskas RW, Forbes NS. Salmonella typhimurium lacking ribose chemoreceptors localize in tumor quiescence and induce apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3201–3209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clairmont C, Lee KC, Pike J, et al. Biodistribution and genetic stability of the novel antitumor agent VNP20009, a genetically modified strain of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181(6):1996–2002. doi: 10.1086/315497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Immune escape of tumors: apoptosis resistance and tumor counterattack. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;71(6):907–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao M, Yang M, Li X-M, et al. Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy with amino acid auxotrophs of GFP-expressing Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:755–760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408422102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Low KB, Ittensohn M, Luo X, et al. Construction of VNP20009: a novel, genetically stable antibiotic-sensitive strain of tumor-targeting Salmonella for parenteral administration in humans. Methods Mol. Med. 2004;90:47–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao M, Yang M, Ma H, et al. Targeted therapy with a Salmonella typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7647–7652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Avogadri F, Martinoli C, Petrovska L, et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on killing of Salmonella-infected tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(9):3920–3927. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee CH, Hsieh JL, Wu CL, Hsu HC, Shiau AL. B cells are required for tumor-targeting Salmonella in host. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;92(6):1251–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee CH, Hsieh JL, Wu CL, Hsu PY, Shiau AL. T cell augments the antitumor activity of tumor-targeting Salmonella. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;90(4):1381–1388. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thamm DH, Kurzman ID, King I, et al. Systemic administration of an attenuated, tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium to dogs with spontaneous neoplasia: phase I evaluation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(13):4827–4834. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yam C, Zhao M, Hayashi K, Ma H, et al. Monotherapy with a tumor-targeting mutant of S. typhimurium inhibits liver metastasis in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2010;164(2):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Momiyama M, Zhao M, Kimura H, et al. Inhibition and eradication of human glioma with tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium in an orthotopic nude-mouse model. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(3):628–632. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.3.19116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elson G, Dunn-Siegrist I, Daubeuf B, Pugin J. Contribution of Toll-like receptors to the innate immune response to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Blood. 2007;109(4):1574–1583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-032961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang B, Zhao J, Shen S, et al. Listeria monocytogenes promotes tumor growth via tumor cell toll-like receptor 2 signaling. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4346–4352. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tye H, Kennedy CL, Najdovska M, et al. STAT3-driven upregulation of TLR2 promotes gastric tumorigenesis independent of tumor inflammation. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(4):466–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kelly MG, Alvero AB, Chen R, et al. TLR-4 signaling promotes tumor growth and paclitaxel chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(7):3859–3868. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baneyx F, Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22(11):1399–1408. doi: 10.1038/nbt1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rocha EP, Danchin A. An analysis of determinants of amino acids substitution rates in bacterial proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21(1):108–116. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Galán JE. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science. 1999;284:1322–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galan JE. Salmonella interactions with host cells: type III secretion at work. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2001;17:53–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Samudrala R, Heffron F, Mcdermott JE. Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(4):e1000375. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sory MP, Boland A, Lambermont I, Cornelis GR. Identification of the YopE and YopH domains required for secretion and internalization into the cytosol of macrophages, using the cyaA gene fusion approach. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92(26):11998–12002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bernhardt TG, Roof WD, Young R. Genetic evidence that the bacteriophage phi X174 lysis protein inhibits cell wall synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(8):4297–4302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bernhardt TG, Struck DK, Young R. The lysis protein E of phi X174 is a specific inhibitor of the MraY-catalyzed step in peptidoglycan synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(9):6093–6097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Witte A, Wanner G, Lubitz W, Holtje JV. Effect of phi X174 protein E-mediated lysis on murein composition of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998;164(1):149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stritzker J, Weibel S, Hill PJ, Oelschlaeger TA, Goebel W, Szalay AA. Tumor-specific colonization, tissue distribution, and gene induction by probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in live mice. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;297(3):151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Burns MR, Wood SJ, Miller KA, Nguyen T, Cromer JR, David SA. Lysine-spermine conjugates: hydrophobic polyamine amides as potent lipopolysaccharide sequestrants. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13(7):2523–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Loessner H, Endmann A, Leschner S, et al. Remote control of tumour-targeted Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by the use of L-arabinose as inducer of bacterial gene expression in vivo. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(6):1529–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cronin CA, Gluba W, Scrable H. The lac operator-repressor system is functional in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2001;15(12):1506–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.892001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sutton MD, Smith BT, Godoy VG, Walker GC. The SOS response: recent insights into umuDC-dependent mutagenesis and DNA damage tolerance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2000;34:479–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mengesha A, Dubois L, Lambin P, et al. Development of a flexible and potent hypoxia-inducible promoter for tumor-targeted gene expression in attenuated Salmonella. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006;5(9):1120–1128. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.9.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen J, Yang B, Cheng X, et al. Salmonella-mediated tumor-targeting TRAIL gene therapy significantly suppresses melanoma growth in mouse model. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(2):325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ryan RM, Green J, Williams PJ, et al. Bacterial delivery of a novel cytolysin to hypoxic areas of solid tumors. Gene Ther. 2009;16(3):329–339. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Song LZ, Hobaugh MR, Shustak C, Cheley S, Bayley H, Gouaux JE. Structure of staphylococcal alpha-hemolysin, a heptameric transmembrane pore. Science. 1996;274(5294):1859–1866. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vandana S, Raje M, Krishnasastry MV. The role of the amino terminus in the kinetics and assembly of alpha-hemolysin of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(40):24858–24863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dinges MM, Orwin PM, Schlievert PM. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13(1):16–34. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.16-34.2000. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Taylor BN, Mehta RR, Yamada T, et al. Noncationic peptides obtained from azurin preferentially enter cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2):537–546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yamada T, Hiraoka Y, Das Gupta TK, Chakrabarty AM. Regulation of mammalian cell growth and death by bacterial redox proteins: relevance to ecology and cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(6):752–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamada T, Goto M, Punj V, et al. Bacterial redox protein azurin, tumor suppressor protein p53, and regression of cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(22):14098–14103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222539699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamada T, Hiraoka Y, Ikehata M, et al. Apoptosis or growth arrest: Modulation of tumor suppressor p53’s specificity by bacterial redox protein azurin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(14):4770–4775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400899101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Apiyo D, Wittung-Stafshede P. Unique complex between bacterial azurin and tumor-suppressor protein p53. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;332(4):965–968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chaudhari A, Mahfouz M, Fialho AM, et al. Cupredoxin-cancer interrelationship: azurin binding with EphB2, interference in EphB2 tyrosine phosphorylation, and inhibition of cancer growth. Biochemistry. 2007;46(7):1799–1810. doi: 10.1021/bi061661x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Suzuki S, Nakasato M, Shibue T, Koshima I, Taniguchi T. Therapeutic potential of proapoptotic molecule Noxa in the selective elimination of tumor cells. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(4):759–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seo YW, Shin JN, Ko KH, et al. The molecular mechanism of Noxa-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in p53-mediated cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(48):48292–48299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang L, Lopez H, George NM, Liu X, Pang X, Luo X. Selective involvement of BH3-only proteins and differential targets of Noxa in diverse apoptotic pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18(5):864–873. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Seo YW, Woo HN, Piya S, et al. The cell death-inducing activity of the peptide containing Noxa mitochondrial-targeting domain is associated with calcium release. Cancer Res. 2009;69(21):8356–8365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yagita H, Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ, Okumura K. TRAIL and its receptors as targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(10):777–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kelley SK, Harris LA, Xie D, et al. Preclinical studies to predict the disposition of Apo2L/tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in humans: characterization of in vivo efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299(1):31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leblanc HN, Ashkenazi A. Apo2L/TRAIL and its death and decoy receptors. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10(1):66–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, et al. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364(6440):806–809. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rensing-Ehl A, Frei K, Flury R, et al. Local Fas/APO-1 (CD95) ligand-mediated tumor cell killing in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25(8):2253–2258. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Groot AJ, Mengesha A, Van Der Wall E, Van Diest PJ, Theys J, Vooijs M. Functional antibodies produced by oncolytic clostridia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;364(4):985–989. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Agrawal N, Bettegowda C, Cheong I, et al. Bacteriolytic therapy can generate a potent immune response against experimental tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(42):15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406242101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Osaki T, Hashimoto W, Gambotto A, et al. Potent antitumor effects mediated by local expression of the mature form of the interferon-gamma inducing factor, interleukin-18 (IL-18) Gene Ther. 1999;6(5):808–815. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Micallef MJ, Tanimoto T, Kohno K, Ikeda M, Kurimoto M. Interleukin 18 induces the sequential activation of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes to protect syngeneic mice from transplantation with Meth A sarcoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57(20):4557–4563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Trinchieri G, Matsumoto-Kobayashi M, Clark SC, Seehra J, London L, Perussia B. Response of resting human peripheral blood natural killer cells to interleukin 2. J. Exp. Med. 1984;160(4):1147–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.4.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lanier LL, Benike CJ, Phillips JH, Engleman EG. Recombinant interleukin 2 enhanced natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity in human lymphocyte subpopulations expressing the Leu 7 and Leu 11 antigens. J. Immunol. 1985;134(2):794–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Phillips JH, Gemlo BT, Myers WW, Rayner AA, Lanier LL. In vivo and in vitro activation of natural killer cells in advanced cancer patients undergoing combined recombinant interleukin-2 and LAK cell therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1987;5(12):1933–1941. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.12.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Woldbaek PR, Sande JB, Stromme TA, et al. Daily administration of interleukin-18 causes myocardial dysfunction in healthy mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;289(2):H708–H714. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01179.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shalmi CL, Dutcher JP, Feinfeld DA, et al. Acute renal dysfunction during interleukin-2 treatment: suggestion of an intrinsic renal lesion. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990;8(11):1839–1846. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.11.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Palmer DH, Milner AE, Kerr DJ, Young LS. Mechanism of cell death induced by the novel enzyme-prodrug combination, nitroreductase/CB1954, and identification of synergism with 5-fluorouracil. Br. J. Cancer. 2003;89(5):944–950. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Knox RJ, Friedlos F, Jarman M, Roberts JJ. A new cytotoxic, DNA interstrand crosslinking agent, 5-(aziridin-1-yl)-4-hydroxylamino-2-nitrobenzamide, is formed from 5-(aziridin-1-yl)-2,4-dinitrobenzamide (CB 1954) by a nitroreductase enzyme in Walker carcinoma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1988;37(24):4661–4669. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Heap JT, Theys J, Ehsaan M, Kubiak AM, et al. Spores of Clostridium engineered for clinical efficacy and safety cause regression and cure of tumors in vivo. Oncotarget. 2014;5(7):1761–1769. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Senzer N, et al. Pilot trial of genetically modified, attenuated Salmonella expressing the E. coli cytosine deaminase gene in refractory cancer patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10(10):737–744. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Langemann T, Koller VJ, Muhammad A, Kudela P, Mayr UB, Lubitz W. The Bacterial Ghost platform system: production and applications. Bioeng. Bugs. 2010;1(5):326–336. doi: 10.4161/bbug.1.5.12540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Huter V, Szostak MP, Gampfer J, et al. Bacterial ghosts as drug carrier and targeting vehicles. J. Control Release. 1999;61(1–2):51–63. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Witte A, Wanner G, Blasi U, Halfmann G, Szostak M, Lubitz W. Endogenous transmembrane tunnel formation mediated by phi X174 lysis protein E. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172(7):4109–4114. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.4109-4114.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Felnerova D, Kudela P, Bizik J, et al. T cell-specific immune response induced by bacterial ghosts. Med. Sci. Monit. 2004;10(10):BR362–BR370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Paukner S, Kohl G, Lubitz W. Bacterial ghosts as novel advanced drug delivery systems: antiproliferative activity of loaded doxorubicin in human Caco-2 cells. J. Control Release. 2004;94(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Macdiarmid JA, Brahmbhatt H. Minicells: versatile vectors for targeted drug or si/shRNA cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011;22(6):909–916. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Carleton HA, Lara-Tejero M, Liu X, Galan JE. Engineering the type III secretion system in non-replicating bacterial minicells for antigen delivery. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1590. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Macdiarmid JA, Mugridge NB, Weiss JC, et al. Bacterially derived 400 nm particles for encapsulation and cancer cell targeting of chemotherapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(5):431–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.03.012. • In-depth study about the use of minicells for chemotherapeutical delivery.

- 132.Macdiarmid JA, Amaro-Mugridge NB, Madrid-Weiss J, et al. Sequential treatment of drug-resistant tumors with targeted minicells containing siRNA or a cytotoxic drug. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27(7):643–651. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chen DJ, Osterrieder N, Metzger SM, et al. Delivery of foreign antigens by engineered outer membrane vesicle vaccines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(7):3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805532107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gujrati V, Kim S, Kim SH, Min JJ, Choy HE, Kim SC, Jon S. Bioengineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles as cell-specific drug-delivery vehicles for cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2014;8(2):1525–1537. doi: 10.1021/nn405724x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhao M, Suetsugu A, Ma HY, et al. Efficacy against lung metastasis with a tumor-targeting mutant of Salmonella typhimurium in immunocompetent mice. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(1):187–193. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.1.18667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]