Abstract

The Prp43 DExD/H-box protein is required for progression of the biochemically distinct pre-messenger RNA and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) maturation pathways. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Spp382/Ntr1, Sqs1/Pfa1, and Pxr1/Gno1 proteins are implicated as cofactors necessary for Prp43 helicase activation during spliceosome dissociation (Spp382) and rRNA processing (Sqs1 and Pxr1). While otherwise dissimilar in primary sequence, these Prp43-binding proteins each contain a short glycine-rich G-patch motif required for function and thought to act in protein or nucleic acid recognition. Here yeast two-hybrid, domain-swap, and site-directed mutagenesis approaches are used to investigate G-patch domain activity and portability. Our results reveal that the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patches differ in Prp43 two-hybrid response and in the ability to reconstitute the Spp382 and Pxr1 RNA processing factors. G-patch protein reconstitution did not correlate with the apparent strength of the Prp43 two-hybrid response, suggesting that this domain has function beyond that of a Prp43 tether. Indeed, while critical for Pxr1 activity, the Pxr1 G-patch appears to contribute little to the yeast two-hybrid interaction. Conversely, deletion of the primary Prp43 binding site within Pxr1 (amino acids 102–149) does not impede rRNA processing but affects small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) biogenesis, resulting in the accumulation of slightly extended forms of select snoRNAs, a phenotype unexpectedly shared by the prp43 loss-of-function mutant. These and related observations reveal differences in how the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 proteins interact with Prp43 and provide evidence linking G-patch identity with pathway-specific DExD/H-box helicase activity.

Keywords: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, spliceosome, rRNA processing, DExD/H-box protein, pre-mRNA splicing

NUMEROUS genome-wide interaction and gene expression studies identify ribosome biogenesis as a central integrative feature of Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism (see, e.g ., Mnaimneh et al. 2004; Davierwala et al. 2005; Gavin et al. 2006; Collins et al. 2007; Hu et al. 2007; Magtanong et al. 2011). In rapidly dividing organisms such as this budding yeast, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) make up the lion’s share of cellular nucleic acid by mass, while ribosomal protein transcripts can account for more than half the transcribed messenger RNA (mRNA). Because ribosome biogenesis is so energetically costly, eukaryotes have evolved multiple means to regulate rRNA and ribosomal protein production in response to changes in cellular demand and surveillance systems to remove aberrant ribosomal protein complexes formed during assembly or after environmental insult (Jorgensen et al. 2002; Fingerman et al. 2003; Fromont-Racine et al. 2003; Jorgensen et al. 2004; Marion et al. 2004; Henras et al. 2008; Kressler et al. 2010; Lafontaine 2010). The coordination of pre-mRNA processing with ribosome biogenesis is especially relevant in the intron-poor environment of the yeast genome, where the highly expressed ribosomal protein transcripts represent a disproportionate amount of the spliced mRNA (Ares et al. 1999; Staley and Woolford 2009). Our understanding of how this coordination is accomplished is limited, however, to general principles supported by a few specific examples where individual ribosomal proteins act as feedback regulators to inhibit the processing or stability of cognate ribosomal protein transcripts (Li et al. 1995, 1996; Vilardell et al. 2000; Pleiss et al. 2007; Gudipati et al. 2012).

The chemistry of pre-mRNA splicing and the initial stages of rRNA processing occur in spatially separable nuclear locations catalyzed by distinct macromolecular machineries. Pre-rRNA processing involves more than 200 proteins and includes 75 small nucleolar RNA particles (snoRNPs) composed of C/D- or H/ACA-box small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) with associated conserved sets of proteins (Grandi et al. 2002; Fromont-Racine et al. 2003; Reichow et al. 2007; Kressler et al. 2010; Phipps et al. 2011). The nuclear pre-mRNA splicing enzyme is likewise complex and composed of roughly 80 yeast proteins and 5 essential small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) (Fabrizio et al. 2009; Pena et al. 2009). Although largely nonoverlapping in composition, the pre-rRNP and spliceosomal complexes share a limited number of factors, including the essential Snu13 protein constituent of the U3 (preribosomal) snoRNP and the U4 (spliceosomal) snRNP and the phylogenetically conserved DEAH-box protein Prp43. DEAH-box proteins are structurally related members of the DExD/H-box family of RNA-dependent NTPases that resolve RNA/RNA helices or act as RNPases to dissociate protein-RNA interactions during macromolecular assembly/disassembly events (Linder and Jankowsky 2011; Cordin et al. 2012; Rodriguez-Galan et al. 2013). In vitro, DExD/H-box proteins typically act as nonspecific NTP/ATPases, with a subset showing nucleic acid strand separation or helicase activity. With few exceptions (see, e.g., Schwer 2008; Hahn et al. 2012; Mozaffari-Jovin et al. 2012), the RNA features or trans-acting factors contributing to helicase substrate specificity in vivo remain unknown.

While the 19 RNA helicases implicated in ribosome biogenesis typically are restricted to either large- or small-subunit-delimited steps, Prp43 promotes multiple RNA processing events in both 25S and 18S rRNA maturation (Lebaron et al. 2005; Combs et al. 2006; Leeds et al. 2006; Bohnsack et al. 2009; Rodriguez-Galan et al. 2013). The yeast Prp43 protein and its mammalian homolog DHX15 also act to dislodge the intron from the postcatalytic spliceosome and to recycle essential snRNP factors for use in subsequent rounds of splicing (Arenas and Abelson 1997; Martin et al. 2002; Tsai et al. 2005; Wen et al. 2008; Fourmann et al. 2013). Prp43 activity contributes to the maintenance of spliceosome integrity because reduced Prp43 function promotes the use of structurally aberrant spliceosomes and the splicing of suboptimal pre-mRNA substrates (Pandit et al. 2006; Koodathingal et al. 2010; Mayas et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2013). In addition to features of the postcatalytic spliceosome, specific changes in spliceosome composition linked to ATP hydrolysis by the Prp2, Prp16, and Prp22 DExD/H-box proteins render defective splicing complexes sensitive to Prp43 recruitment and ATP-dependent dissociation (Chen et al. 2013).

Data from several groups implicate three Prp43-interacting factors in the regulation of this protein’s role in pre-mRNA splicing (Spp382/Ntr1) and pre-rRNA processing (Sqs1/Pfa1 and Pxr1/Gno1) (Guglielmi and Werner 2002; Lebaron et al. 2005; Tsai et al. 2005; Boon et al. 2006; Pandit et al. 2006; Tanaka et al. 2007; Tsai et al. 2007; Lebaron et al. 2009; Pertschy et al. 2009; Walbott et al. 2010; Christian et al. 2014). Spp382 is an essential pre-mRNA splicing factor required for Prp43 recruitment to the spliceosome. Pxr1 is necessary for efficient rRNA maturation at the A0, A1, and A2 processing sites and plays a second, separable role in the final steps of Rrp6-dependent 3′-end processing of snoRNAs. Sqs1 is not required for efficient yeast growth but appears to play a nonessential role in 20S to 18S rRNA processing by the Nob1 endonuclease. Although otherwise dissimilar in sequence, the Spp382, Pxr1, and Sqs1 proteins each contain a weakly conserved 45- to 50-amino-acid glycine-rich G-patch motif (Pfam: PF01585) (Punta et al. 2012) found in select RNA-associated proteins (Aravind and Koonin 1999). Point mutations within the SPP382, PXR1, and SQS1 G-patch coding segments can block or weaken the corresponding protein interaction with Prp43 and inhibit pre-mRNA splicing or rRNA processing (Guglielmi and Werner 2002; Pandit et al. 2006; Tanaka et al. 2007; Lebaron et al. 2009). In addition, Spp382 and Sqs1 peptides bearing the G-patch domain stimulate the RNA-dependent helicase activity of Prp43 in vitro (Tanaka et al. 2007; Lebaron et al. 2009; Christian et al. 2014). While critical to each protein’s biological activity, prior work leaves unresolved whether the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch domains are equivalent interfaces that promote a common Prp43 activity or serve a more complex function in the pre-mRNA splicing and rRNA processing pathways.

Here we report the results of experiments to investigate Prp43–G-patch protein interaction and to probe the role of the G-patch domain in Prp43-sensititive RNA biogenesis. The data show that although the G-patch is sufficient to interact with Prp43, the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch peptides differ in yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) response and in the ability to reconstitute Spp382 activity in splicing and Pxr1 activity in rRNA processing. Point mutagenesis of the G-patch domain shows that functional reconstitution of Spp382 is sequence dependent but does not directly correlate with strength of the Prp43 Y2H response. The Prp43-Pxr1 interaction was found to be largely G-patch independent and driven by an ∼50-amino-acid Pxr1 peptide found downstream of the G-patch motif. Curiously, while efficient Pxr1-dependent rRNA processing does not require this Pxr1 domain, loss of either this site or diminished Prp43 activity results in snoRNA processing defects. These observations support a model in which G-patch identity contributes pathway-sensitive information relevant to Prp43 function in the parallel processes of pre-mRNA splicing and rRNA maturation and suggest an unanticipated role for Prp43 activity in snoRNA processing.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and culture

The yeast strains used in this study are presented in Table 1. The oligonucleotides used for cloning and mutagenesis are listed in Supporting Information, Figure S1. Yeast cultures were grown in YEP medium (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, made 2% with glucose or galactose) prior to plasmid transformation by the lithium chloride method (Ito et al. 1983). For all other purposes, yeast cultures were grown on synthetic complete medium with single or double amino acid dropouts as needed (Kaiser et al. 1994).

Table 1. Yeast Strains.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SP102 | a ura3Δ0 trp1-289 leu2 Δ0 his3 Δ1 spp382::KAN and p416-GAL1::spp382-4 | Pandit et al. 2006 |

| pJ69-4a | a trp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80 Δ LYS2:: GAL1–HIS3 GAL2–ADE2 met2:: GAL7–lacZ | James et al. 1996 |

| LZΔpxr1 | a pxr1:: KAN leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 his3Δ1 | T. Zhang and B. C. Rymond, unpublished material |

| BY4742 | α his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Winzeler et al. 1999 |

| prp43H218A | α ura3-52, trp1-63, his3 Δ200, leu2-1, ade2-101, ade2-101, lys2-801, prp43::KAN, p358-prp43H218A, TRP1 | Martin et al. 2002 |

| PRP43 | α ura3-52, trp1-63, his3 Δ200, leu2-1, ade2-101, ade2-101, lys2-801, prp43::KAN, p358-PRP43, TRP1 | Martin et al. 2002 |

Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays

The SPP382 and SQS1 yeast pACT Y2H constructs were described previously (Pandit et al. 2006, 2009). The protein coding sequences of gene derivatives new to this study were fused to the GAL4 activation-domain (AD) and/or the GAL4 GAL4 DNA binding-domain (BD) sequences in the plasmids pACT2 and pAS2 (Harper et al. 1993), respectively, and transformed into yeast strain pJ69-4a (James et al. 1996). To compare the relative Y2H responses of yeast transformants, the strains were first cultured to saturation, collected by centrifugation, and washed twice with sterile water. Next, the cultures were normalized to equivalent OD600 values, and four 10-fold serial dilutions of each culture were spotted on dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan for simple growth of the double transformant or, for GAL1-HIS3 reporter-gene assay, medium lacking histidine supplemented with 5–20 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) where indicated. The two-hybrid response was scored by overall spot density and, in the most dilute samples, relative colony size after 2–4 days of incubation at 23 or 30° on selective medium.

Plasmid constructs

The spp382ΔG-patch deletion construct was made by inverse PCR from the previously described YCplac111-SPP382 plasmid (Pandit et al. 2006) using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and oligonucleotide primers with terminal SacII sites flanking G-patch domain codons 61–108. The corresponding SPP382, SQS1, and PXR1 G-patch add-back cassettes were amplified from BY4742 genomic DNA by PCR with primers containing terminal SacII sites and inserted into the SacII site of YCplac111-spp382ΔG. An equivalent PCR-based strategy was used to create the ΔG-patch and G-patch segment add-back derivatives in the pACT-SPP382 background (Pandit et al. 2009). The pxr1 G-patch point mutations were introduced by inverse PCR on a pTZ18U-PXR1 G-patch subclone, and the mutated segments were subsequently transferred into the YCplac111-spp382ΔG or into the pACT-spp382ΔG plasmid background as SacII DNA fragments. Where indicated, URA3-based plasmids were removed by plasmid shuffle on medium containing 0.75 mg/ml 5-floroorotic acid (FOA) (Boeke et al. 1987).

The wild-type (WT) PXR1 gene was amplified by PCR from BY4742 yeast genomic DNA with primers placed 300 bp upstream and downstream of the ORF (Figure S1) and cloned into the Kpn1 site of plasmid YCplac111. The G-patch domain was subsequently deleted from the YCplac111-PXR1 construct by inverse PCR with primers flanking this domain. PCR-amplified SPP382, SQS1, and PXR1 G-patch cassettes were introduced into the linearized YCplac111-pxr1ΔG plasmid as blunt-ended DNA fragments. For the Y2H study, the PXR1 ORF was inserted into the SmaI site of pACT2. The indicated PXR1 domain deletions were introduced into pACT2-PXR1 by inverse PCR. The PXR1 102–149 and 150–226 codon single-domain constructs were made similarly by PCR fragment insertion into pACT2.

The PRP43 deletions were constructed by inverse PCR on pAS2-PRP43 (Pandit et al. 2009) with domain-specific primers (Figure S1). The Prp43 single-domain Y2H constructs were amplified with oligonucleotides containing 5′-terminal NdeI sites (NTD, Ratchet, and WH domains) or BamHI sites (RecA1, RecA2, and CTD) inserted into corresponding restriction sites on pAS2. The prp43H218A mutant allele and its WT PRP43 counterpart expressed from plasmid p352 were described previously (Martin et al. 2002).

RNA methods

The yeast cultures were grown at 30° to an OD600 of 0.4 in selective dropout medium, collected by centrifugation, and washed twice with ice-cold RNA extraction (RE) buffer (100 mM LiCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 1 mM EDTA), and the pellets were stored at −80° until needed. The cold-sensitive prp43(H218A) mutant and its isogenic PRP43 control culture were grown for 15 hr at 17° prior to cell harvest. Yeast culture conditions for the isolation of RNA from the SP102 transformants after glucose repression of the GAL1::spp382-4 gene were described previously (Pandit et al. 2006).

For RNA isolation, the cell pellets were broken with a Mini-Beadbreaker (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for 4 min in 400 µl of RE buffer, 150 µl of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (PCI, 50:48:2), and 300 µl of sterile glass beads (0.5 mm diameter; Biospec Products). The cellular debris, glass beads, and PCI were removed by centrifugation at 18,000×g for 3 min at 4°. The supernatant was PCI extracted three additional times, followed by a final chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Then 20 µg of RNA was resolved on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, transferred to an Immobilon+ membrane, and then hybridized with random prime-labeled probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) against RPS17A, ADE3, or U6 snRNA under standard conditions (Sambrook et al. 1989). Alternatively, 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide probes were used to detect the rRNA precursor, intermediates, and products and snR128 and snR18 (Figure S1) using previously published conditions (Guglielmi and Werner 2002; Kos and Tollervey 2005). The bands of hybridization were visualized with a Typhoon 8600 Phosphoimager and quantified with ImageQuant software after background subtraction (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA).

Protein methods

Prior to harvest, the yeast cultures were grown at 30° to an OD600 of 2–4 in selective dropout medium. Protein extraction was performed as described previously (Zhang et al. 2011). Briefly, 7 OD of culture was collected by centrifugation (14,000×g for 1 min) and the pellets resuspended in 500 µl of 2 M LiOAc for 5 min at room temperature. The cells then were recovered by centrifugation and resuspended in 500 µl of 0.4 M NaOH for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were again collected by centrifugation and finally resuspended in 250 µl of gel sample buffer [0.06 M-Tris-HC1, pH 6.8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.0025% (w/v) bromophenol blue] (Horvath and Riezman 1994) and heated at 100° for 10 min. The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation as earlier, and 75 µg of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE (7.5 or 10% polyacrylamide). The resolved proteins were electroblotted to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and Western blot images were obtained using a 1:1500 dilution of the HA.11 anti-HA antibody (Covance, Princeton, NJ) for the pACT2 and pAS2 vector constructs or an anti-Gal4 activation-domain antibody (1:500 dilution; sc-1663; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for the Spp382-bearing pACT constructs. The pAS2-Prp43 construct also was imaged using the mouse monoclonal anti-Gal4 DNA binding domain antibody (1:500 dilution; sc-577). Mouse monoclonal antibody 12G10 (1:1000 dilution; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) was used to image α-tubulin as a loading control. Secondary antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase diluted 1:1500 in PBS/5% nonfat dry milk were used for protein detection with the ECF Detection Module (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) or the BCIP/NBT In Situ Detection System (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). All antibodies were diluted in PBS made 5% w/v with nonfat dry milk. The ECF or scanned BCIP/NBT band intensities were quantified with ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Results

Isolated Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch peptides interact with Prp43 but differ in Y2H response

When the full-length G-patch proteins are scored by the Y2H assay for interaction with Prp43, we find a graded response in GAL1-HIS3 reporter-gene-dependent growth of Spp382 ≥ Sqs1 > Pxr1 > empty vector (Figure 1A). Because the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 proteins lack obvious sequence similarity beyond the G-patch (Figure 1B), this element likely functions, at least in part, as a common Prp43 binding feature. In support of this, we find that the isolated G-patch segments also interact with Prp43 by the Y2H assay in the order of Spp382 > Sqs1 > Pxr1, with the Pxr1 G-patch showing a Y2H response near that of the empty-vector control. Both the Sqs1 and Pxr1 G-patch Y2H interactions with Prp43 are lost when the assay is made more stringent for reporter-gene activation by the addition of 5 mM 3-aminotriazole (James et al. 1996), reinforcing the less robust Prp43 Y2H response of these peptides (data not shown). While some experimental variability in protein abundance was observed, the three G-patch peptides are similarly expressed, with the Sqs1 peptide generally accumulating to somewhat higher amounts (∼twofold) than the Spp382 or Pxr1 G-patch peptides (Figure S2). It is possible that G-patch peptide abundance contributes to the differential Prp43 Y2H response, although, as argued below, sequence differences also appear to affect Prp43 interaction. Regardless, the Y2H responses show that at least for the Spp382 and Sqs1 proteins, the G-patch domain is sufficient for Prp43 interaction in vivo.

Figure 1.

Differential Y2H interaction of the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch peptides with Prp43. (A) Y2H assay performed in the yeast pJ69-4a reporter strain transformed with full-length PRP43 as a GAL4 DNA binding-domain (BD) fusion and the indicated full-length or G-patch-only gene segments as GAL4 activation-domain (AD) fusions. Tenfold serial dilutions were plated on medium that selects for the double-plasmid transformants (-leu -trp, 2 days’ growth) or for reporter-gene transactivation (-his, 3.5 days’ growth) at 30°. (B) Amino acid alignment of the G-patch sequences from yeast proteins Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1. The numbers refer to the G-patch positions within each protein. The G-patch peptides show 32–34% amino acid identity in each pairwise comparison. Sequence identities are shaded and indicated as a consensus for 2/3 (lowercase) and 3/3 (uppercase) matches, respectively.

Since the isolated G-patch peptides interact with Prp43 less well than the full-length proteins, other portions of the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 proteins likely stabilize the Prp43 Y2H associations. For Sqs1, a second site of Prp43 interaction has been reported within the first 202 amino acids of this protein, and as expected, the Sqs1ΔG protein continues to interact well with Prp43 (Figure 2A) (Lebaron et al. 2009; Pandit et al. 2009). A second site of Prp43 interaction is also present in the central portion of Pxr1 (see below). The Pxr1ΔG-Prp43 Y2H response is not noticeably diminished compared with the full-length Pxr1-Prp43 interaction, consistent with limited Pxr1–G-patch contribution to this association (Figure 2A). Consistent with an earlier report by Tsai et al. (2005), deletion of Spp382 G-patch blocks all detectable Prp43 interaction. While Spp382 and Pxr1 Y2H Gal4 fusion proteins accumulate to similar levels, Sqs1 is always found at much lower abundance, roughly 5–10% of this level based on the intensities of the common Gal4 activation-domain epitope by Western blot analysis (Figure 2C; compare lanes 4 and 5 with lanes 2 and 3 and 6–10). This lower abundance is surprising given its comparatively robust Sqs1-Prp43 Y2H response, although it is possible that shorter proteolytic fragments also contribute to the Y2H response. In no case does G-patch removal destabilize the Gal4 fusion proteins. Therefore, the lack of Spp382ΔG-Prp43 Y2H interaction is not due to protein instability, and other sites of Prp43 contact, if present within Spp382, are insufficient to promote stable Y2H association.

Figure 2.

Prp43 activators differ in G-patch reliance for Y2H interaction. (A) Y2H assay as described in Figure 1A between Prp43 and the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 constructs before and after G-patch removal. (B) Y2H assay between Prp43 and full-length Spp382, the G-patch deletion derivative (spp382ΔG), and the constructs reconstituted from this deletion mutant by addition of the Spp382, Pxr1, or Sqs1 G-patch coding sequences. The -his medium used in panels A and B contained 5 mM 3-aminotriazole, and the plates were incubated for 4 days at 30°. (C) Western blot analysis of the Y2H proteins expressed as pACT-Gal4 activation fusions. The proteins were imaged with antibodies against the Gal4 activation domain (upper panel; Spp382, Spp382ΔG, Sqs1, Sqs1ΔG, Pxr1, Pxr1ΔG, and the Spp382ΔG construct reconstituted with the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch), the Gal4 DNA binding-domain panel (middle panel; Prp43), and anti-α-tubulin (lower panel). The blots were developed using BCIP/NBT (Gal4 activation-domain antibody, α-tubulin antibody) and ECF (Gal4 DNA binding-domain antibody). The asterisks in the top panel indicate the positions of the three sets of G-patch proteins. For unknown reasons, the Sqs1 fusion proteins run more slowly than the similarly sized Spp382 proteins. The numbers to the left in the top panel refer to the sizes (in kDa) of the protein markers run in lane 1. After normalization with the tubulin control, the Gal-4 activation-domain band intensities were found to vary less than twofold with the exception of the full-length Sqs1 and Sqs1ΔG proteins, which are reproducibly found at 5–10% of the Spp382 and Pxr1 levels.

Insertion of either the cognate Spp382 G-patch or the Sqs1 G-patch coding sequence into the spp382ΔG construct restores the Spp382-Prp43 interaction, showing that, at least in this assay, flexibility is permitted in G-patch motif (Figure 2B). A heterologous G-patch cassette might restore Prp43 interaction through direct contact or by changing the conformation of Spp382 in a such manner as to expose another site of interaction, possibly by acting as an appropriately configured spacer. The simple spacer model is unlikely, however, because an equivalently constructed Spp382-Pxr1 chimera is equally well expressed but fails to interact above background with Prp43 in the Y2H assay (Figure 2, B and C). Thus, a legitimate, albeit weakly interacting G-patch motif is insufficient to reconstitute stable Spp382-Prp43 association. The spp382-PXR1 two-hybrid construct also weakly inhibits growth in the absence of reporter-gene selection (Figure 2B, smaller individual colony sizes in left panel; see below), suggesting that the chimeric protein may sequester an important RNA processing factor in an inactive complex. Yeast toxicity was reported previously with SQS1 overexpression (Pandit et al. 2009), although this is less pronounced when expressed as a Y2H construct.

Spp382 G-patch identity is important for splicing-factor function

We next asked whether the differences in Prp43 Y2H interaction observed with the Spp382–G-patch chimeras correlate with changes in Spp382 biological activity. To do this, we repeated the domain-swap experiment in an otherwise intact SPP382 gene and scored the resulting chimeric derivatives for complementation of an spp382::KAN null mutation (Winzeler et al. 1999). To avoid complications from overexpression, the SPP382-chimeric genes were cloned on a single-copy LEU2-marked centromeric plasmid vector transcribed with the native SPP382 promoter. Because the spp382::KAN mutation is lethal, the chimeric genes were first transformed into yeast that coexpress the biologically active and nutritionally regulated GAL1-spp382-4 allele (Pandit et al. 2006) and subsequently scored for independent function after GAL1-spp382-4 removal by plasmid shuffle. None of the chimeric constructs cause obvious growth inhibition when coexpressed with GAL1-spp382-4 on galactose medium (Figure 3, left panel). As anticipated, deletion of the G-patch segment inactivates SPP382 and results in a lethal (FOA) phenotype, while reinsertion of the cognate SPP382 G-patch coding segment restores activity (Figure 3, right panel). Equivalent results were obtained when these constructs were scored for complementation by meiotic segregation (data not shown). Comparable to what was seen with the Prp43 Y2H response, the Spp382-Sqs1 G-patch chimeric protein is functional and supports growth, albeit at a reduced level. The reduced growth corresponds to an ∼50% increase in doubling time in liquid medium compared with the SPP382 control (Figure 3 and Figure S3). In contrast, the spp382-PXR1 G-patch chimera mimics the empty-vector control and is unable to rescue spp382::KAN lethality.

Figure 3.

G-patch identity affects Spp382 function. Complementation of the lethal spp382::KAN mutation with a LEU2-marked plasmid bearing the WT SPP382 gene, the G-patch deletion derivative, or the deletion derivative reconstituted with the SPP382, SQS1 or PXR1 G-patch coding sequences. These were initially cotransformed with the biologically active URA3-marked GAL1-spp382-4 plasmid that supports growth on a galactose-based medium. Tenfold serial dilutions were plated on galactose (left) and glucose-based medium supplemented with 5-fluoroorotic acid (right) to select for yeast that have lost the URA3-marked GAL1-spp382-4 plasmid.

Functional G-patch reconstitution of the Spp382 splicing factor does not correlate with the strength of the Y2H response

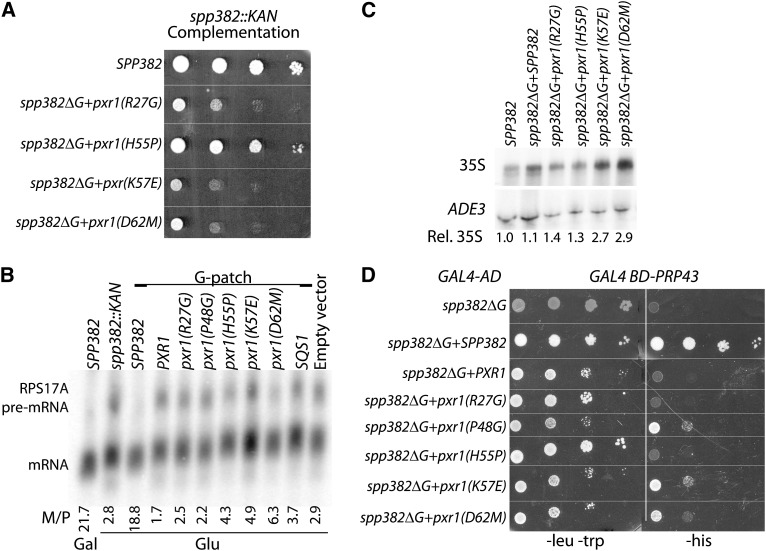

The results presented earlier show that G-patch identity contributes context-specific information and suggest a possible relationship between Prp43 binding and G-patch protein function, specifically, that strong Prp43–G-patch interaction is favored for the Spp382 protein and that weaker Prp43–G-patch interaction is favored by Pxr1. In principle, differential G-patch affinity might contribute to the dynamics of Prp43 association with (or function within) the rRNA processing and pre-mRNA splicing machineries. To further investigate this relationship, we introduced point mutations within the G-patch domain of the spp382-PXR1 G-patch chimera and scored the mutated constructs for spp382::KAN complementation. In each case, the amino acid substitution converts the Pxr1 G-patch residue into the amino acid naturally present at the same position within the Spp382 G-patch (Figure 1B). The sites of mutagenesis were guided in part by the pattern of phylogenetic conservation (Figure S4, A and B) and include residues where protein family-specific differences appear to occur (i.e., R27G, H55P, and K57E; the numbered coordinates refer to the amino acid positions within Pxr1) as well as residues where conservation is less apparent (P48G and D62M). The spp382-PXR1 (WT) and spp382-pxr1(P48G) chimeras do not support viability after removal of the cotransformed GAL1-spp382-4 gene (Figure 3, and data not show). In contrast, spp382-pxr1 G-patch chimeric constructs containing the R27G, H55P, K57E, and D62M mutations complement spp382::KAN (Figure 4A). There is considerable variation in culture growth, however, with H55P functioning much better than the others. While histidine is common at position 55 among Pxr1 homologs, approximately 65% of the 2124 G-patch peptides listed in the SMART protein domain database (Letunic et al. 2012) show proline at the equivalent location, including yeast Spp382 (P90) and Sqs1 (P750). This residue is not essential for Spp382 function, however, because alanine, histidine, or serine substitution in an otherwise WT SPP382 background has little impact on growth (Figure S5). Rather, the proline becomes critical in the context of the Spp382-Pxr1 chimera, which, in essence, contains the equivalent of a multiply mutated Spp382 G-patch.

Figure 4.

RNA splicing activity of the Spp382-Pxr1 chimeras correlates with growth but not with the relative Prp43 Y2H response. (A) Complementation of the lethal spp382::KAN mutation by SPP382 and the viable pxr1 chimeric constructs (R27G, H55P, K57E, and D62M) after removal of GAL1-spp382-4 plasmid by FOA selection. Tenfold serial dilutions were plated on synthetic complete medium and grown at 30° for 3 days. Chimeras containing the WT PXR1 G-patch or the P48G derivative are lethal (see Figure 3) and cannot be assayed in this way. (B) Northern blot analysis of RPS17A pre-mRNA splicing. The spp382::KAN mutant transformed with the functional GAL1-spp382-4 allele was assayed before (Gal) and after (Glu) transcriptional repression. The strains were cotransformed with plasmids containing the spp382ΔG plasmid reconstituted with the WT SPP382, PXR1, or SQS1 G-patch, the indicated mutant PXR1 G-patch, or an empty vector. Splicing efficiency is presented as the ratio of mRNA/pre-mRNA band intensity below each lane. The mRNA and most pre-mRNA molecules are polyadenylated and resolve as a pair of broad bands by Northern blot after transfer from a denaturing 1% agarose gel. (C) Northern blot analysis of 35S rRNA accumulation and the ADE3 loading control in WT yeast and spp382 ΔG gene reconstituted with the indicated G-patch peptide coding sequences. The 35S signal intensities relative to the WT are presented after normalization with the ADE3 control (Rel. 35S). (D) Y2H assay between PRP43 and SPP382-PXR1 G patch chimeras containing point mutations within the G-patch domain. SPP382 constructs lacking the G-patch or containing the WT SPP382 or PXR1 G-patch domains are shown as controls. Serial dilutions of saturated cultures are plated for double transformant viability (-leu, -trp) and two-hybrid reporter activation (-his supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotriazole).

We next monitored the efficiency of pre-mRNA processing in the spp382-PXR1 G-patch chimeras after transcriptional repression of the GAL1-spp382-4 gene. Yeast that express GAL1-spp382-4 on galactose-based medium splice pre-mRNA well, whereas glucose repression of GAL1-spp382-4 for 12 hr inhibits splicing and results in a fivefold or greater reduction in the ratio of processed to unprocessed RPS17A RNA (Figure 4B) (see Pandit et al. 2006). Yeast cotransformed with the spp382ΔG derivative process pre-mRNA no better than the empty-vector control, but splicing can be reconstituted with insertion of the cognate SPP382 G-patch segment. Although incomplete GAL1-spp382-4 repression overestimates splicing efficiency for the strongest mutants, the splicing patterns and growth characteristics of yeast transformed with the chimeric plasmids agree in direction, if not magnitude. Here the spp382-PXR1 chimera and the noncomplementing P48G construct behave no better than the empty-vector control, while the biologically active spp382-Sqs1 G-patch add-back and the viablepxr1 chimeric mutant chimeric derivatives (with the possible exception of the R27G) show modestly improved splicing. Two viable chimeras with weak spp382::KAN complementation activity, K57E and D62M, also show pronounced rRNA processing defects, with two- to threefold increases in 35S rRNA precursor RNA compared with the other backgrounds (Figure 4C).

The Prp43 Y2H interaction pattern does not correlate directly with the pattern of spp382::KAN complementation by the mutated spp382-pxr1 constructs. Here the H55P chimera, which best supports spp382::KAN complementation, performs similarly to the noncomplementing chimera bearing a WT PXR1 G-patch in the Y2H assay (Figure 4D). In vitro, G-patch-containing peptides expressed from spp382-PXR1 and spp382-pxr1(H55P) alleles show greater salt sensitivity for Prp43 interaction than the equivalent Spp382 peptide, consistent with lower affinity (Figure S6). In contrast, the more weakly complementing D62M and K57E chimeras and the noncomplementing P48G construct all support modestly greater Prp43 Y2H response, even though each construct is somewhat toxic when expressed without two-hybrid reporter selection (Figure 4D; compare left and right panels relative to SPP382-reconstituted and spp382ΔG control constructs). While recognizing that these are very subtle distinctions, spp382-pxr1 derivatives are similarly expressed as Y2H constructs (Figure S7), arguing against differences in Gal4 activation-domain abundance contributing to the differential Y2H response. Taken together, these data show that while G-patch identity affects Spp382-Prp43 protein interaction, effective reconstitution of the Spp382 splicing factor requires G-patch function beyond that contributing to stable Prp43 interaction.

Pxr1 G-patch chimeras show variation in rRNA processing activity

The studies presented earlier establish an overlapping but not identical contribution of the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch domains in the context of the Spp382 pre-mRNA splicing factor, with the Sqs1 G-patch being more Spp382-like in reconstituting Prp43 interaction and biological activity. We next considered G-patch portability in the context of the Pxr1 rRNA processing factor. To do this, the PXR1 G-patch sequence was first removed by inverse PCR and then replaced with the cognate PXR1 G-patch sequence or with a heterologous cassette from the SPP382 or SQS1 genes. Plasmids containing the chimeric PXR1 G-patch constructs then were assayed for complementation of the viable, albeit very slowly growing pxr1::KAN null mutant (Winzeler et al. 1999).

Deletion of the G-patch (amino acids 25–72) inactivates Pxr1 because the pxr1ΔG transformant grows no better than the untransformed pxr1::KAN parental host (Figure 5A) (see Guglielmi and Werner 2002). Reinsertion of the PXR1 G-patch or the SQS1 G-patch sequence into pxr1ΔG restores efficient growth, while substitution of the SPP382 G-patch improves growth but at a much reduced level compared to what is seen with the intact PXR1 allele. The same complementation pattern is seen when rRNA processing rather than yeast growth is monitored. As reported previously, the loss of Pxr1 activity inhibits rRNA processing, most obvious here as increased accumulation of the 35S rRNA precursor and the generally low-abundance 23S processing intermediate (Figure 5B) (see Guglielmi and Werner 2002). The pxr1::KAN parental host and the pxr1ΔG mutant display equivalent rRNA processing defects consistent with the G-patch deletion allele having a null phenotype. Protein reconstruction with the cognate Pxr1 G-patch peptide restores full activity, while insertion of either the Sqs1 or Spp382 G-patch peptides supports partial function, with the Sqs1 add-back showing a more complete recovery of rRNA processing efficiency. Thus, similar to what was seen with the Spp382 chimeras, some flexibility in G-patch structure is tolerated in Pxr1, here again with the Sqs1 G-patch serving as the preferred heterologous cassette.

Figure 5.

The Pxr1-specified G-patch is optimal for rRNA processing activity. (A) Complementation of the viable but slow-growing pxr1::KAN mutation with plasmid-borne copies of native PXR1 gene, the G-patch depletion derivative, pxr1ΔG, and reconstituted derivatives bearing the original PXR1 G-patch or chimeric SQS1 or SPP382 G-patch coding sequences. Saturated cultures of the indicated genotypes were plated as serial 10-fold dilutions on complete medium and incubated for 2 days at 30°. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from logarithmically grown cultures of the genotypes described in A. The samples were resolved by denaturing 1.2% agarose formaldehyde gel electrophoresis and probed with previously described oligonucleotides (Kos and Tollervey 2005) specific for the indicated 35S rRNA precursor, intermediates (23S, 20S, and 7S), and products (25S, 18S, and 5.8S). An ADE3 mRNA probe is used as a loading control. Samples from untransformed yeast (UT) and plasmid-transformed strains in the pxr1::KAN background indicated. After normalization with the ADE3 signals, the WT, the 35S rRNA abundance is unchanged in the pxr1ΔG-PXR1 transformant and increased 5.7-, 4.1-, 2.6-, and 1.7-fold in the pxr1::KAN, pxr1ΔG, pxr1ΔG+SPP382, and pxr1ΔG+SQS1 transformants, respectively.

The primary Prp43 binding site within Pxr1 is not required for efficient rRNA biogenesis but contributes to snoRNA processing activity

Since removal of the G-patch inactivates Pxr1 for rRNA processing but not Prp43 binding, additional sites of Prp43 contact must exist within Pxr1. To define sequences critical for Prp43 association, we created a set of PXR1 deletion derivatives guided by prior domain characterization (Figure S8) (see Guglielmi and Werner 2002) and scored each for Prp43 Y2H interaction (Figure 6A). Removal of codons 102–149 or overlapping segments almost completely blocks Prp43 interaction, although this derivative is stable and present at levels equivalent to the full-length Pxr1 or Pxr1ΔG (Figure S9). Since no other deletions greatly reduced the Y2H response, the primary Prp43 binding site of Pxr1 appears to reside within this peptide. This prediction was confirmed in a complementary experiment where the isolated 48-amino-acid peptide was found to be sufficient for Prp43 interaction when expressed at levels similar to poorly interacting Pxr1 G-patch (Figure 6B and Figure S9).

Figure 6.

Loss of main Prp43 binding site has little impact on Pxr1 rRNA processing activity. (A) Y2H assay between PRP43 and the indicated PXR1 deletion derivatives. The G-patch domain is deleted in the Δ25–72 construct, and the KKE/D domain common to certain nucleolar proteins is deleted in the Δ150–226 segment. Serial dilutions of saturated cultures are plated for cell number (-leu, -trp) and two-hybrid reporter activation (-his supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotriazole) and incubated for 2 days at 30°. (B) Y2H assay as described in A with Gal4 activation-domain constructs limited to the proposed primary Prp43 binding site (102–149), the KKE/D domain (150–226), full-length PXR1, or an empty vector. Here the histidine-deficient medium was supplemented with 20 mM 3-AT to suppress background trans-activation observed with the pxr1(150–226) construct. (C) Complementation of the pxr1::KAN growth defect by plasmid-based copies of the full-length gene (PXR1) or the indicated deletion constructs. The transformants were grown for 3 days at 30° on selective medium. (D) Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from logarithmically grown cultures shown in C probed for the 35S pre-rRNA and the ADE3 mRNA loading control. The relative 35S intensities were determined as described in Figure 5.

Surprisingly, removal of the primary Prp43 binding site (i.e., PXR1 codons 102–149) had negligible impact on pxr1::KAN complementation (Figure 6C). Likewise, this deletion does not result in excess 35S rRNA accumulation or obvious downstream defects in rRNA processing (Figure 6D and data not shown). A larger deletion, pxr1Δ102-226, inactivates Pxr1, but unlike the Pxr1Δ102–149 derivative, this protein could not be reproducibly detected by Western blot as a Y2H peptide and likely may not be stable (Figure 6, C and D, and Figure S9). While conceivable that the 102–149 and 150–226 peptides act redundantly in support of Pxr1 function, deletion of the 150–226 peptide has negligible impact on the Prp43 Y2H interaction (Figure S9). The 150–226 peptide contains a so-called KKE/D domain characteristic of certain nucleolar proteins (e.g., Nop56p, Nop58p, Cbf5p, and Dbp3p) (see Gautier et al. 1997). Consistent with earlier reports, removal of this domain does not interfere with rRNA processing (Figure 6D) (see Guglielmi and Werner 2002). The isolated 150–226 peptide segment does not appreciably interact with Prp43 by the Y2H assay, although interpretation of this observation is complicated by the fact that expression of the Pxr1(150–226) Y2H construct somewhat impairs growth (Figure 6B). Nevertheless, together these data support the surprising conclusions that although the G-patch is essential for Pxr1 function, it appears to interact poorly with Prp43, while the primary Prp43 binding site within Pxr1 is dispensable for rRNA processing activity.

Consistent with prior studies implicating Pxr1 in snoRNA 3′-end processing, deletion of the PXR1 gene or removal of the G-patch or Pxr1 150–226 domain coding sequences results in the accumulation of snR18 (U18 snoRNA, 102 nt) transcripts bearing approximately three nucleotide extensions compared to WT transcripts (Figure 7) (see Guglielmi and Werner 2002). We find that the pxr1Δ102–149 mutant behaves equivalently, showing at least three times as much of the extended form than the properly processed 102-nt snR18 transcript. Remarkably, extended-length snoRNAs also accumulate when Prp43 function is compromised by the characterized prp43(H218A) mutant with diminished ATPase activity (Martin et al. 2002) compared with an isogenic strain bearing the WT PRP43 allele. The magnitude of the extended RNA response is snoRNA specific, and longer RNA forms were not observed for the126-nt snR128 (U14 snoRNA) or the 112-nt snR6 (U6) RNAs previously reported as insensitive to the loss of Pxr1 activity (Guglielmi and Werner 2002). Thus, the impaired activity of either the Prp43 helicase or its Pxr1binding partner alters the biogenesis of certain snoRNAs.

Figure 7.

Loss of the Prp43 binding site within Pxr1 or diminished Prp43 activity alters U18 snoRNA processing. Northern blot hybridization of RNA isolated from WT yeast (lanes 2 and 4), the prp43H218A mutant (lane 3), yeast with a full PXR1 deletion (lanes 1 and 7), or the pxr1Δ150–226 (lane 5) and pxr1Δ102–149 deletion (lane 6) derivatives. The prp43H218A and its WT control are otherwise isogenic (lanes 2 and 3), as are the pxr1 mutant derivatives and their WT control (lanes 1 and 4–7). The membrane was sequentially hybridized with oligonucleotide probes specific for the snR18 (U18), snR128 (U14), and snR6 (U6) RNAs.

Prp43 domains required for stable G-patch protein interaction

To identify possible sites of G-patch protein contact, we constructed a series of PRP43 deletion derivatives and assayed each for Y2H interaction with genes that express the full-length Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 proteins (Figure 8). The endpoints of the deletions were guided by the domains described in the recently resolved Prp43 structure (He et al. 2010; Walbott et al. 2010). To stabilize potentially weak associations, the deletion derivatives were assayed at 23° rather than at the typical growth temperature of 30°. Deletions of the Prp43 N-terminal domain (amino acids 7–94), the ratchet domain (amino acids 522–635), and much of the C-terminal domain including the entire OB fold required for full RNA binding and ATPase stimulation (amino acids 649–748) (see Walbott et al. 2010) resulted in little or no decrease in Y2H-dependent growth, showing that these regions are not critical for stable Prp43 association. In contrast, removal of RecA2 (amino acids 271–457) blocks interaction with all three G-patch protein partners. Since the RecA2-deleted Prp43 protein is stably expressed (Figure S10), this domain appears critical for G-patch protein interaction by the Y2H assay. Deletion of either the RecA1 domain (amino acids 95–270) or the winged helix domain (WH; amino acids 455–542) differentially affects Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 Y2H interactions, possibly reflecting differences in non-G-patch contacts. Here, removal of RecA1 from Prp43 blocks or severely impairs Y2H interaction with Spp382 and Sqs1 but has a less profound effect on Pxr1. In contrast, removal of the WH domain blocks Pxr1 and Sqs1 association with Prp43, while Spp382 continues to interact, albeit less well than with the full-length Prp43. Each of the deletion constructs is expressed at levels roughly between 50 and 100% of full-length Prp43. Similar results were obtained when the interactions were assayed at 30°, although a weakened response was seen between the Prp43 ratchet deletion mutant and Sqs1, and all interaction was lost between Spp382 and the Prp43 WH-domain deletion constructs. Complementary Y2H experiments using the three full-length G-patch proteins failed to provide convincing evidence for independent interaction with any isolated Prp43 domain. Although the ratchet peptide was found at considerably lower abundance, the remaining Prp43 domains were stably expressed (Figure S11), suggesting that G-protein association may require multiple, perhaps discontinuous regions of Prp43 for a robust Y2H response. We note, however, that the Prp43 WH domain showed high levels of reporter-gene activation in the absence of a Y2H partner, prohibiting unambiguous assessment of this construct.

Figure 8.

G-patch protein sensitivity to Prp43 domain deletions. The numbered positions above the diagram refer to the amino acid coordinates previously used to describe Prp43 domain organization (He et al. 2010; Walbott et al. 2010). Below this diagram are bars showing the sites of deletion with amino acid coordinates for the residues removed for Y2H analysis. The Y2H results for full-length Prp43 and each deletion construct are summarized for the three G-patch proteins. In each case, growth observed with the full-length constructs is set at +++, with the deletion mutants showing equivalent growth (+++) or colonies roughly half this size (++), visible colonies one-quarter this size or smaller (+), or no visible colonies (−). The plate cultures were grown for 4 days at 23° on medium lacking histidine and supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotrazole.

Discussion

The G-patch peptide motif binds Prp43 and is required to stimulate the RNA-dependent ATPase and helicase activities of this DExD/H-box enzyme (Tanaka et al. 2007; Walbott et al. 2010; Christian et al. 2014). If this is the sole function of the G-patch, one might expect that equivalent segments of the three putative Prp43 activators would have similar properties and be interchangeable in support of enzyme function. The results presented here reveal a more nuanced situation and implicate G-patch involvement beyond service as a simple Prp43 interface.

While not a highly quantitative assay, the Y2H approach provides a qualitative measure of protein interaction in vivo (Uetz and Hughes 2000). We find that Prp43 interacts with the isolated G-patch peptide domains in the Y2H response order Spp382 > Sqs1 > Pxr1. Differences in G-patch peptide expression are unlikely to account for the negligible Pxr1G-patch–Prp43 Y2H response, suggesting an intrinsically weak interaction between this peptide protein pair. This view is bolstered by the more salt-sensitive Prp43 interaction observed in vitro with the peptides bearing the Pxr1 G-patch compared with those containing the Spp383 G-patch. The negligible Pxr1 G-patch domain–Prp43 Y2H response, the failure of the Pxr1 G-patch to functionally reconstitute Spp382, and the lack of biochemical data documenting Prp43 helicase activation by Pxr1 raise the question of whether Pxr1 is a legitimate Prp43 partner. While definitive proof is still wanting, the legitimacy of this association is supported by the G-patch dependence on Pxr1 recovery in Prp43 complexes (Chen et al. 2014) and the rRNA processing defects observed in pxr1 mutants consistent with Prp43 involvement (Guglielmi and Werner 2002). In addition, the human PXR1 homolog, PINX1, has been shown to complement a yeast pxr1 null mutant, and in vitro, the PinX1 protein stimulates yeast Prp43 ATPase activity (Guglielmi and Werner 2002; Chen et al. 2014). Based on this, we think that it most likely that the Spp382, Sqs1, and Pxr1 G-patch peptides all naturally bind Prp43 but differ in apparent affinity due to optimization for cis- or trans-acting interactions distinct for each protein. Each of the three Prp43 binding partners as scored here requires sequences outside the G-patch domain for maximal Y2H response. In addition to the observations presented here, poorly conserved sequences flanking the Spp382 G-patch were shown recently to enhance G-patch-dependent Prp43 activation in vitro (Christian et al. 2014) and add to this peptide’s association with Prp43. However, extrapolating from our Y2H results, Pxr1 interaction with Prp43 association appears largely independent of the G-patch, suggesting that transient or weak association with this motif in the context of the native RNP is sufficient for helicase function.

Prp43 truncated at amino acid 657 fails to bind a Sqs1 G-patch peptide in vitro, implicating the final 15% of Prp43 as a primary contact site for G-patch association (Walbott et al. 2010). The Prp43 C-terminus contains an OB-fold oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding domain thought to interact with RNA and necessary for full G-patch-stimulated enzyme activity. Lysine residues within this domain can be chemically cross-linked with the Spp382 G-patch consistent with close and perhaps direct contact between these peptide features (Christian et al. 2014). Similar interactions are predicted to occur between the C-terminus of the Prp2 DEAH-box helicase and its G-patch activator, Spp2 (Roy et al. 1995; Silverman et al. 2004; Warkocki et al. 2015). It was surprising, therefore, that the large Prp43 C‐terminal domain (CTD) deletion scored here had no discernible impact on G-patch-dependent Spp382-Prp43 Y2H interaction. We do not think it likely that residual CTD sequences in our construct (i.e., amino acids 749–767) are sufficient for stable Spp382 contact because the final 35 amino acids of Prp43 are not needed for Prp43 activity in vivo (Tanaka et al. 2007). Functional redundancy between the CTD and RecA2 domains of Prp43 has been suggested based on identification of prp43 RecA2 missense mutations that inhibit Spp382 G-patch helicase stimulation in vitro and that exacerbate CTD lesions in vivo (Tanaka et al. 2007). This portion of the enzymatic core is especially attractive as a critical site of G-patch contact because its removal also blocks G-patch-dependent Spp382 interaction. Since Sqs1 and Pxr1 likewise fail to bind the Prp43ΔRecA2 derivative, RecA2 either directly participates in their non-G-patch interactions or indirectly fosters contact through proper folding of the Prp43 protein.

At a functional level, the Spp382 and Pxr1 G-patch domains are largely incompatible in chimeric protein reconstitution, while the equivalently dissimilar Sqs1 G-patch (Figure 1B) serves as an acceptable compromise cassette in either context. Point mutations introduced to make the Pxr1 G-patch more Spp382-like were found to modestly improve the Prp43 Y2H interaction (i.e., D62M, K57E, and P48G) or restore biological activity to the chimeric Spp382-Pxr1 splicing factor (i.e., H55P, D62M, K57E, and R27G). The H55P substitution showed the most robust response in Spp382 reconstitution, converting the otherwise nonfunctional spp382-PXR1 allele to one that supported growth at roughly half the rate of an otherwise isogenic WT control. Curiously, the HPP5 did not detectably enhance this protein’s Y2H interaction with Prp43. While both assays show that multiple G-patch residues contribute to domain specificity, there was not a tight correlation between improved Prp43 interaction and spp382::KAN complementation. However, since antibodies are not available for the native G-patch protein, differential impact on RNA processing protein stability cannot be ruled out. This caveat aside, G-patch function beyond simple Prp43 recognition provides a reasonable explanation for Spp382 and Pxr1 G-patch incompatibility. For instance, the G-patch may promote proper folding of the cognate protein through cis interactions or bind trans-acting factors specific for the splicing or rRNA processing machineries to enhance the Prp43 affinity or RNP specificity (Figure 9). Unfortunately, the only G-patch proteins for which structural data are currently available show this segment as disordered, leaving unresolved the nature of cis interactions (Frenal et al. 2006; Christian et al. 2014).

Figure 9.

Alternate models for G-patch contribution to pathway-dependent Prp43 function. In each case, Prp43 activity requires G-patch interaction for enzyme activation. Pathway specificity may be added as illustrated by (1) intramolecular interactions that alter the effectiveness of G-patch protein stimulation of Prp43, (2) direct G-patch contact with the substrate RNA, or (3) G-patch interaction with protein specificity factors guiding Prp43 recruitment to the spliceosome or pre-ribosomal particle. The G-patch is indicated by the clustered filled circles. Stable association of the G-patch protein with Prp43 is illustrated but cofactor dissociation and is also consistent with the existing literature.

For trans-acting associations, the RNA substrate is a possible G-patch target because in vitro studies conducted with the TgDRE DNA repair enzyme of Toxoplasma gondii (Frenal et al. 2006) and the mouse retroviral proteases MIA-14 and MPMV (Svec et al. 2004) suggest intrinsic G-patch affinity for nucleic acid. More directly, K67 of the Spp382 G-patch motif can be ultraviolet (UV) cross-linked to RNA in vitro when coincubated with Prp43, indicating at least transient RNA contact with this domain (Christian et al. 2014). It is conceivable that G-patch–RNA association contributes to the Prp43 Y2H responses seen here and, more important, enhances productive Prp43 interaction with its sites of cellular RNA contact in spliceosome and ribosomal complexes (Bohnsack et al. 2009).

We have shown that a 48-amino-acid peptide downstream of the Pxr1 G-patch provides stable Prp43 contact in the Y2H assay. While deletion of this sequence virtually eliminates the Pxr1-Prp43 Y2H interaction, it has little impact on G-patch-dependent cell growth or rRNA processing. Removal of this element does, however, promote the accumulation of slightly extended snR18 RNAs, a characteristic seen with several other pxr1 mutant alleles and proposed to result from aberrant 3′-end processing (Guglielmi and Werner 2002). In fact, 3′-extended snoRNAs, including polyadenylated species, also accumulate when snoRNA transcriptional termination is blocked, snoRNP assembly is disrupted by Nop58 or Nop1 depletion, or exosome activity is impaired (see Allmang et al. 1999; Grzechnik and Kufel 2008; Costello et al. 2011; Garland et al. 2013). While commonly thought to target stable RNAs for degradation (Lacava et al. 2005; Vanacova et al. 2005; Wyers et al. 2005), some 3′-extended RNAs escape this fate (Grzechnik and Kufel 2008), and the snR18+3 transcripts found in the pxr1 mutants appear stable and accumulate to levels equivalent to those of the properly processed RNAs in the WT background. The presence of similarly extended snR18 RNAs in the prp43H218A mutant raises the intriguing possibility that this protein also has a role in snoRNA biogenesis. Conceivably, this could occur as an indirect consequence of impaired pre-mRNA splicing in the prp43H218A background (Martin et al. 2002). However, because snoRNP recruitment to and release from pre-ribosomal particles is directly affected by the loss of Prp43 activity (Bohnsack et al. 2009), perhaps a more likely explanation is that defects in ribosome biogenesis contribute to the extended snoRNA phenotype. Going forward, it will be important to learn whether Pxr1-Prp43 contact is required for proper snoRNA maturation and, more generally, to refine our understanding of the network of G-patch protein interactions underpinning Prp43 contribution to the pre-mRNA, rRNA, and snoRNA maturation pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Beate Schwer for providing the cloned PRP43 and prp43H281A genes, Michael Fried for valuable suggestions during the course of this work, and Martha Peterson, Stefan Stamm, Doug Harrison, and Swagata Ghosh for helpful comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by the Linda and Jack Gill Endowment and National Institutes of Health award GM-42476 to BCR.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.176461/-/DC1

Communicating editor: M. Hampsey

Literature Cited

- Allmang C., Kufel J., Chanfreau G., Mitchell P., Petfalski E., et al. , 1999. Functions of the exosome in rRNA, snoRNA and snRNA synthesis. EMBO J. 18: 5399–5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L., Koonin E. V., 1999. G-patch: a new conserved domain in eukaryotic RNA-processing proteins and type D retroviral polyproteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24: 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas J. E., Abelson J. N., 1997. Prp43: an RNA helicase-like factor involved in spliceosome disassembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 11798–11802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares M., Jr, Grate L., Pauling M. H., 1999. A handful of intron-containing genes produces the lion’s share of yeast mRNA. RNA 5: 1138–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke J. D., Trueheart J., Natsoulis G., Fink G. R., 1987. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 154: 164–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack M. T., Martin R., Granneman S., Ruprecht M., Schleiff E., et al. , 2009. Prp43 bound at different sites on the pre-rRNA performs distinct functions in ribosome synthesis. Mol. Cell 36: 583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon K. L., Auchynnikava T., Edwalds-Gilbert G., Barrass J. D., Droop A. P., et al. , 2006. Yeast ntr1/spp382 mediates prp43 function in postspliceosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 6016–6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. C., Tseng C. K., Tsai R. T., Chung C. S., Cheng S. C., 2013. Link of NTR-mediated spliceosome disassembly with DEAH-box ATPases Prp2, Prp16, and Prp22. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33: 514–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. L., Capeyrou R., Humbert O., Mouffok S., Kadri Y. A., et al. , 2014. The telomerase inhibitor Gno1p/PINX1 activates the helicase Prp43p during ribosome biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 7330–7345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian H., Hofele R. V., Urlaub H., Ficner R., 2014. Insights into the activation of the helicase Prp43 by biochemical studies and structural mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 1162–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. R., Kemmeren P., Zhao X. C., Greenblatt J. F., Spencer F., et al. , 2007. Toward a comprehensive atlas of the physical interactome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6: 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs D. J., Nagel R. J., Ares M., Jr, Stevens S. W., 2006. Prp43p is a DEAH-box spliceosome disassembly factor essential for ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 523–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordin O., Hahn D., Beggs J. D., 2012. Structure, function and regulation of spliceosomal RNA helicases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24: 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello J. L., Stead J. A., Feigenbutz M., Jones R. M., Mitchell P., 2011. The C-terminal region of the exosome-associated protein Rrp47 is specifically required for box C/D small nucleolar RNA 3′-maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 4535–4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davierwala A. P., Haynes J., Li Z., Brost R. L., Robinson M. D., et al. , 2005. The synthetic genetic interaction spectrum of essential genes. Nat. Genet. 37: 1147–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P., Dannenberg J., Dube P., Kastner B., Stark H., et al. , 2009. The evolutionarily conserved core design of the catalytic activation step of the yeast spliceosome. Mol. Cell 36: 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman I., Nagaraj V., Norris D., Vershon A. K., 2003. Sfp1 plays a key role in yeast ribosome biogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 2: 1061–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourmann J. B., Schmitzova J., Christian H., Urlaub H., Ficner R., et al. , 2013. Dissection of the factor requirements for spliceosome disassembly and the elucidation of its dissociation products using a purified splicing system. Genes Dev. 27: 413–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenal K., Callebaut I., Wecker K., Prochnicka-Chalufour A., Dendouga N., et al. , 2006. Structural and functional characterization of the TgDRE multidomain protein, a DNA repair enzyme from Toxoplasma gondii. Biochemistry 45: 4867–4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont-Racine M., Senger B., Saveanu C., Fasiolo F., 2003. Ribosome assembly in eukaryotes. Gene 313: 17–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland W., Feigenbutz M., Turner M., Mitchell P., 2013. Rrp47 functions in RNA surveillance and stable RNA processing when divorced from the exoribonuclease and exosome-binding domains of Rrp6. RNA 19: 1659–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier T., Berges T., Tollervey D., Hurt E., 1997. Nucleolar KKE/D repeat proteins Nop56p and Nop58p interact with Nop1p and are required for ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 7088–7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin A. C., Aloy P., Grandi P., Krause R., Boesche M., et al. , 2006. Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature 440: 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi P., Rybin V., Bassler J., Petfalski E., Strauss D., et al. , 2002. 90S pre-ribosomes include the 35S pre-rRNA, the U3 snoRNP, and 40S subunit processing factors but predominantly lack 60S synthesis factors. Mol. Cell 10: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzechnik P., Kufel J., 2008. Polyadenylation linked to transcription termination directs the processing of snoRNA precursors in yeast. Mol. Cell 32: 247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudipati R. K., Neil H., Feuerbach F., Malabat C., Jacquier A., 2012. The yeast RPL9B gene is regulated by modulation between two modes of transcription termination. EMBO J. 31: 2427–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi B., Werner M., 2002. The yeast homolog of human PinX1 is involved in rRNA and small nucleolar RNA maturation, not in telomere elongation inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 35712–35719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn D., Kudla G., Tollervey D., Beggs J. D., 2012. Brr2p-mediated conformational rearrangements in the spliceosome during activation and substrate repositioning. Genes Dev. 26: 2408–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. W., Adami G. R., Wei N., Keyomarsi K., Elledge S. J., 1993. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 75: 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Andersen G. R., Nielsen K. H., 2010. Structural basis for the function of DEAH helicases. EMBO Rep. 11: 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henras A. K., Soudet J., Gerus M., Lebaron S., Caizergues-Ferrer M., et al. , 2008. The post-transcriptional steps of eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65: 2334–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A., Riezman H., 1994. Rapid protein extraction from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10: 1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Killion P. J., Iyer V. R., 2007. Genetic reconstruction of a functional transcriptional regulatory network. Nat. Genet. 39: 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A., 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153: 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P., Halladay J., Craig E. A., 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two- hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144: 1425–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen P., Nishikawa J. L., Breitkreutz B. J., Tyers M., 2002. Systematic identification of pathways that couple cell growth and division in yeast. Science 297: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen P., Rupes I., Sharom J. R., Schneper L., Broach J. R., et al. , 2004. A dynamic transcriptional network communicates growth potential to ribosome synthesis and critical cell size. Genes Dev. 18: 2491–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C., Michaelis S., Mitchell A. (Editors), 1994. Methods in Yeast Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Koodathingal P., Novak T., Piccirilli J. A., Staley J. P., 2010. The DEAH box ATPases Prp16 and Prp43 cooperate to proofread 5′ splice site cleavage during pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 39: 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos M., Tollervey D., 2005. The putative RNA helicase Dbp4p is required for release of the U14 snoRNA from preribosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 20: 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressler D., Hurt E., Bassler J., 2010. Driving ribosome assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803: 673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCava J., Houseley J., Saveanu C., Petfalski E., Thompson E., et al. , 2005. RNA degradation by the exosome is promoted by a nuclear polyadenylation complex. Cell 121: 713–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine D. L. J., 2010. A “garbage can” for ribosomes: how eukaryotes degrade their ribosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35: 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebaron S., Froment C., Fromont-Racine M., Rain J. C., Monsarrat B., et al. , 2005. The splicing ATPase prp43p is a component of multiple preribosomal particles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 9269–9282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebaron S., Papin C., Capeyrou R., Chen Y. L., Froment C., et al. , 2009. The ATPase and helicase activities of Prp43p are stimulated by the G-patch protein Pfa1p during yeast ribosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 28: 3808–3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeds N. B., Small E. C., Hiley S. L., Hughes T. R., Staley J. P., 2006. The splicing factor Prp43p, a DEAH box ATPase, functions in ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 513–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Doerks T., Bork P., 2012. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D302–D305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Vilardell J., Warner J. R., 1996. An RNA structure involved in feedback regulation of splicing and of translation is critical for biological fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 1596–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Paulovich A. G., Woolford J. L., Jr, 1995. Feedback inhibition of the yeast ribosomal protein gene CRY2 is mediated by the nucleotide sequence and secondary structure of CRY2 pre-mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 6454–6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder P., Jankowsky E., 2011. From unwinding to clamping: the DEAD box RNA helicase family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12: 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magtanong L., Ho C. H., Barker S. L., Jiao W., Baryshnikova A., et al. , 2011. Dosage suppression genetic interaction networks enhance functional wiring diagrams of the cell. Nat. Biotechnol. 29: 505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion R. M., Regev A., Segal E., Barash Y., Koller D., et al. , 2004. Sfp1 is a stress- and nutrient-sensitive regulator of ribosomal protein gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 14315–14322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A., Schneider S., Schwer B., 2002. Prp43 is an essential RNA-dependent ATPase required for release of lariat-intron from the spliceosome. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 17743–17750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayas R. M., Maita H., Semlow D. R., Staley J. P., 2010. Spliceosome discards intermediates via the DEAH box ATPase Prp43p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 10020–10025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnaimneh S., Davierwala A. P., Haynes J., Moffat J., Peng W. T., et al. , 2004. Exploration of essential gene functions via titratable promoter alleles. Cell 118: 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari-Jovin S., Santos K. F., Hsiao H. H., Will C. L., Urlaub H., et al. , 2012. The Prp8 RNase H-like domain inhibits Brr2-mediated U4/U6 snRNA unwinding by blocking Brr2 loading onto the U4 snRNA. Genes Dev. 26: 2422–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit S., Lynn B., Rymond B. C., 2006. Inhibition of a spliceosome turnover pathway suppresses splicing defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 13700–13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit S., Paul S., Zhang L., Chen M., Durbin N., et al. , 2009. Spp382p interacts with multiple yeast splicing factors, including possible regulators of Prp43 DExD/H-box protein function. Genetics 183: 195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena V., Jovin S. M., Fabrizio P., Orlowski J., Bujnicki J. M., et al. , 2009. Common design principles in the spliceosomal RNA helicase Brr2 and in the Hel308 DNA helicase. Mol. Cell 35: 454–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertschy B., Schneider C., Gnadig M., Schafer T., Tollervey D., et al. , 2009. RNA helicase Prp43 and its co-factor Pfa1 promote 20 to 18 S rRNA processing catalyzed by the endonuclease Nob1. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 35079–35091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps K. R., Charette J. M., Baserga S. J., 2011. The small subunit processome in ribosome biogenesis—progress and prospects. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleiss J. A., Whitworth G. B., Bergkessel M., Guthrie C., 2007. Rapid, transcript-specific changes in splicing in response to environmental stress. Mol. Cell 27: 928–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., et al. , 2012. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D290–D301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow S. L., Hamma T., Ferre-D’Amare A. R., Varani G., 2007. The structure and function of small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 1452–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Galan O., Garcia-Gomez J. J., de la Cruz J., 2013. Yeast and human RNA helicases involved in ribosome biogenesis: current status and perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829: 775–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J., Kim K., Maddock J. R., Anthony J. G., Woolford J. L., Jr, 1995. The final stages of spliceosome maturation require Spp2p that can interact with the DEAH box protein Prp2p and promote step 1 of splicing. RNA 1: 375–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T., 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboraory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B., 2008. A conformational rearrangement in the spliceosome sets the stage for Prp22-dependent mRNA release. Mol. Cell 30: 743–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman E. J., Maeda A., Wei J., Smith P., Beggs J. D., et al. , 2004. Interaction between a G-patch protein and a spliceosomal DEXD/H-box ATPase that is critical for splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 10101–10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J. P., Woolford J. L., Jr, 2009. Assembly of ribosomes and spliceosomes: complex ribonucleoprotein machines. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21: 109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec M., Bauerova H., Pichova I., Konvalinka J., Strisovsky K., 2004. Proteinases of betaretroviruses bind single-stranded nucleic acids through a novel interaction module, the G-patch. FEBS Lett. 576: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N., Aronova A., Schwer B., 2007. Ntr1 activates the Prp43 helicase to trigger release of lariat-intron from the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 21: 2312–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai R. T., Fu R. H., Yeh F. L., Tseng C. K., Lin Y. C., et al. , 2005. Spliceosome disassembly catalyzed by Prp43 and its associated components Ntr1 and Ntr2. Genes Dev. 19: 2991–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai R. T., Tseng C. K., Lee P. J., Chen H. C., Fu R. H., et al. , 2007. Dynamic interactions of Ntr1-Ntr2 with Prp43 and with U5 govern the recruitment of Prp43 to mediate spliceosome disassembly. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 8027–8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P., Hughes R. E., 2000. Systematic and large-scale two-hybrid screens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3: 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacova S., Wolf J., Martin G., Blank D., Dettwiler S., et al. , 2005. A new yeast poly(A) polymerase complex involved in RNA quality control. PLoS Biol. 3: e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardell J., Chartrand P., Singer R. H., Warner J. R., 2000. The odyssey of a regulated transcript. RNA 6: 1773–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walbott H., Mouffok S., Capeyrou R., Lebaron S., Humbert O., et al. , 2010. Prp43p contains a processive helicase structural architecture with a specific regulatory domain. EMBO J. 29: 2194–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warkocki Z., Schneider C., Mozaffari-Jovin S., Schmitzova J., Hobartner C., et al. , 2015. The G-patch protein Spp2 couples the spliceosome-stimulated ATPase activity of the DEAH-box protein Prp2 to catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 29: 94–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X., Tannukit S., Paine M. L., 2008. TFIP11 interacts with mDEAH9, an RNA helicase involved in spliceosome disassembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9: 2105–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler E. A., Shoemaker D. D., Astromoff A., Liang H., Anderson K., et al. , 1999. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285: 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyers F., Rougemaille M., Badis G., Rousselle J. C., Dufour M. E., et al. , 2005. Cryptic pol II transcripts are degraded by a nuclear quality control pathway involving a new poly(A) polymerase. Cell 121: 725–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Lei J., Yang H., Xu K., Wang R., et al. , 2011. An improved method for whole protein extraction from yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 28: 795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.