Abstract

Much research has been conducted on ethnic differences in sexuality, but few studies have systematically assessed the importance of acculturation in sexual behavior. The present study assessed general differences in normative sexual practices in healthy Euro-American, Asian, and Hispanic populations, using measures of acculturation to analyze the relative effects of heritage and mainstream cultures within each group. A total of 1,419 undergraduates (67% Euro-American, 17% Hispanic, 16% Asian; 33% men, 67% women) completed questionnaires which assessed sexual experience and causal sexual behaviors. In concordance with previous studies, Asians reported more conservative levels of sexual experience and frequency of sexual behaviors, fewer lifetime partners, and later ages of sexual debut than Euro-American or Hispanic counterparts. Hispanic reported sexual experiences similar to that of Euro-Americans. There was a significant interaction between mainstream and heritage acculturation in predicting number of lifetime sexual partners in Asian women such that the relationship between heritage acculturation and casual sexual behavior was stronger at lower levels of mainstream acculturation. On the other hand, in Hispanic men, higher levels of mainstream acculturation predicted more casual sexual behavior (one-time sexual encounters and number of lifetime sexual partners) when heritage acculturation was low but less casual sexual behavior when heritage acculturation was high. These results suggest that, for sexual behavior, Hispanic men follow an “ethnogenesis” model of acculturation while Asian women follow an “assimilation” model of acculturation.

Keywords: Ethnic differences, Gender differences, Acculturation, Sexuality, Asian, Hispanic, Euro-American

Introduction

It is not merely an oversight to neglect the effects of culture and ethnicity on sexuality. It is a basic threat to the reliability and validity of any conclusion that is applied to the general population (Sue, 1983). According to a 2008 report from the United States Census Bureau, about 1 in 3 Americans is a member of an ethnic minority, with Hispanics and Asians representing the fastest growing groups in the U.S. (United States Census Bureau Population Division, 2008). Despite their growing prominence in the American cultural mosaic, however, these two groups have been underrepresented in studies on sexuality. Moreover, previous studies have focused on group differences rather than the cultural or societal mechanisms which lie behind these differences (Lewis, 2004). Considering the cultural differences among ethnic groups, there is reason to believe that Hispanics and Asians differ in sexual behavior both from each other and from their Euro-American counterparts.

Research to date has generally found that Asians show more conservative rates of sexual behaviors than any other ethnic group studied (for review, see Okazaki, 2002). This has been demonstrated in several age cohorts. In a large, cross-sectional questionnaire study of college students, Meston, Trapnell, and Gorzalka (1996) found that Asian undergraduates at a Canadian university were more sexually conservative than non-Asian students. Asian students were less likely to participate in oral sex, masturbation, petting, and intercourse compared with their non-Asian peers. Asian women were also less likely than non-Asian women or Asian men to report having experienced intercourse. Asian undergraduates typically reported their first sexual encounter at a later age and endorsed a lower frequency of intercourse overall. In contrast, non-Asian students reported a higher lifetime number of sexual partners and single-encounter sexual experiences (i.e., “one night stands”). The Study of Women’s Heath Across the Nation reported that middle-aged Chinese and Japanese women reported less sexual activity than Euro-American women of the same age group (Cain et al., 2003). And finally, Laumann et al. (2005) found in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors that of a sample of people aged 40 and older, East Asians reported lower rates of intercourse (both in the last year and on average) than Euro-Americans, Hispanics, Middle-Easterners, and Africans.

Research on base rates of sexual behavior in Hispanics, on the other hand, have not shown such a clear trend. In the case of sexual intercourse, it appears that Hispanics are as active as Euro-Americans and more active than Asians (Cain et al., 2003). However, gender differences have been fairly clear, with Hispanic men reporting higher levels of sexual permissiveness than Hispanic women. Specifically, it has been found that Hispanic men outrank Hispanic women twofold on measures of sexual permissiveness, such as lifetime number of partners (Kann et al., 2000). Interestingly, while Hispanic women report about half the number of lifetime partners than do Hispanic men, they are about as likely to have engaged in intercourse (Kahn, Rosenthal, Succorp, Ho, & Burk, 2002). Taken together, these findings indicate that although Hispanic women are less likely to have had sex, or to have had multiple partners, they are more likely to be continually sexually active (Driscoll, Biggs, Brindis, & Yankah, 2001).

Members of an ethnic group that is a cultural minority in their nation, rather than the dominant culture, may draw cultural values from not only their heritage culture—the culture of birth or upbringing—but from the mainstream culture (Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). When individuals from one culture integrate into a different culture—either from birth or through immigration—both the self-identity and the relationship to each culture must be modified to accommodate information about and experiences gained from each culture, a process known as acculturation (for review, see Berry, 1997). Thus, measures of acculturation provide greater detail on the effects of culture both between groups and, more importantly, individuals. That is, because acculturation is relative to an individual’s engagement in mainstream and heritage cultural values, it is impossible to capture in categorical, ethnographic group comparisons. Interestingly, acculturation has different trends in different minority groups. It has been suggested that, in North America, Asians typically show the least acculturation while Hispanics show the most (Wong-Rieger & Quintana, 1987). These two groups, it would seem, are ideal for exploring the broad spectrum of acculturation effects.

Generally, it has been found that highly acculturated individuals tend to adopt sexual practices similar to those of the mainstream culture. For example, while Hispanic men are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse at an earlier age than Euro-American men, highly acculturated Hispanic men report similar ages as Euro-American men (Sabogal, Perez-Stable, Otero-Sabogal, &Hiatt, 1995). Similarly, while Hispanic women tend to report a lower number of lifetime partners (Sabogal et al., 1995) and later age for first intercourse (Raffaelli, Zamboanga, & Carlo, 2005) than Euro-American women, highly acculturated Hispanic women tend to report similar sexual histories as their Euro-American counterparts (Marin, Tschann, Gomez,& Kegeles, 1993). Several studies of Asian immigrants to Canada indicate that long-term residents have more “Western” (in this case, liberal) sexual attitudes than residents who recently immigrated (Meston, Trapnell, & Gorzalka, 1998).

Despite these efforts in investigating ethnic group differences, both methodology and findings in such studies have been inconsistent: because many studies use different methods to assess acculturation, some unidimensional (e.g., length of residency) and some dichotomous (“high-low” measures, e.g., preferred language, English or Spanish), results have not often been in agreement. For example, Brindis, Wolfe, McCarter, Ball, and Starbuck-Morales (1995) found that higher levels of acculturation (defined as native or non-native to the U.S.) in Latina teens is associated with higher levels of unplanned (versus planned) teen pregnancy; however, Orshan (1999) found that acculturation was not a significant predictor of planning in Latina teen pregnancies when acculturation was measured using a multi-item questionnaire. Moreover, measures such as length of residency afford less specificity in measuring the relative importance of or exposure to the heritage culture or mainstream culture for each individual. It is possible that two individuals of the same ethnic group, with equal exposure to the mainstream and heritage cultures, may place different levels of emphasis on each, and thus identify with different cultural values (Padilla, 1980).

What is more, most studies on sexual behavior in ethnic minorities have assumed an assimilation model of acculturation—that is, that acculturation occurs in a linear fashion from identification with the heritage to identification with the mainstream culture. Measures of acculturation in these studies have been unidimensional, such as length of residency or successive generations in immigrant families. For example, Abramson and Imai-Marquez (1982) showed that sex guilt decreased across successive generations of Japanese women living in North America. However, assimilation is not the only acculturation strategy used by ethnic minorities: in fact, in a study of several integration strategies (such as assimilation and marginalization, or self-segregation from the mainstream) used by Hispanic youth, Berry, Phinney, Sam, and Vedder (2006) found that biculturalism—that is, mutual engagement in heritage and mainstream cultures—was the most adaptive and most used strategy. It is thus likely that a bidimensional measure of acculturation, which would capture both heritage and mainstream acculturation, would yield more precise findings.

Indeed, it has been found that biculturalism is a better predictor of rates of sexual intercourse in Hispanic women than unidimensional models (Fraser, Piacentini, Van Rossem, Hien, & Rotheram-Borus, 1998; Raffaelli et al., 2005). Similarly, Brotto, Chik, Ryder, Gorzalka, and Seal (2005) showed that the separate measures of heritage and mainstream acculturation were significantly and independently related to sexual attitudes above and beyond length of residency in Canada. Specifically, they found that in East Asian women, while mainstream acculturation significantly predicted sexual experience, sexual dysfunction, and arousal, heritage acculturation did not. Interestingly, the interaction of heritage and mainstream acculturation measures predicted sexual attitudes, indicating that for those women who had maintained strong ties to the heritage culture, mainstream exposure had little to no effect on sexual attitudes (Brotto et al., 2005). It is clear, then, that a bi-dimensional measure of acculturation, where heritage and mainstream acculturation dimensions are measured independently, has the greater validity and utility than unidimensional measures.

Several theoretical frameworks have been put forth to explain acculturation effects on sexual behaviors; however, few studies have directly tested these frameworks(Afable-Munsuz & Brindis, 2006). One such framework is the “cultural norms” theory, which postulates that increasing contact with the mainstream culture introduces new values, which lead to different sexual behaviors (Upchurch, Aneshenel, Mudgal, & McNeely, 2001); in this case, we may expect a main effect of mainstream acculturation on sexual behaviors. Complementary theories suggest that it is successive dissociation with traditional values which stimulates change in successive generations (Tschann et al., 2002); in this case, we may expect a main effect of heritage acculturation. Using a measure that assesses identification with both the heritage and mainstream cultures allows us to differentially examine each of these frameworks.

Because women are, across cultures, more likely to negotiate social systems for their families, they are often the crux point for conflict and compromise between heritage and mainstream cultures (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, Marin, & Perez-Stable, 1987; Young, 2006), and thus there may be a gender by acculturation interaction in Asian and Hispanic men and women. Such interactions may be due to differences in cultural expectations regarding men’s and women’s sexual behavior (Brotto, Woo, & Ryder, 2007). For example, while mainstream acculturation may have a significant impact on Asian women’s sexual behavior, Asian men’s sexual behavior is not as limited by culture and thus acculturation effects may not be as profound.

Indeed, while acculturated Asian-American women are more likely to engage in intercourse than their less acculturated peers, Asian-American men seem to be less affected by level of acculturation (Hahm, Lahiff, & Barreto, 2006). Moreover, the interaction between heritage and mainstream cultures was found to predict sexual experience in Asian women (Brotto et al., 2005) but not men (Brotto et al., 2007). In Hispanics, Ford and Norris (1993) found that highly acculturated men and women were more likely to engage in oral sex, indicating strong acculturative effects regardless of gender. However, while highly acculturated Hispanic women were more likely to engage in anal sex, highly acculturated men were not, indicating that the gender differences in the effect of acculturation was specific to the sexual act. These results imply that the sexual practices of Hispanic and Asian men seem to be less affected by acculturation than those of Hispanic and Asian women.

It is sometimes assumed that Euro-Americans represent the baseline from which all other ethnic groups can be validly compared. Unfortunately, there are two problems with such an approach: firstly, there may be some element of commonality between two groups (e.g., minority status) which is “counted twice” in such a comparison; and secondly, the reasons behind differences between ethnic groups may change dramatically depending on the groups in question. For example, cultural differences may drive down rates of risky sexual behaviors in less acculturated Asian populations while lower socioeconomic status in less acculturated Hispanic populations may drive up these same rates.

The present study expands upon prior research with this problem in mind—by comparing two different non-Euro-American ethnic groups (in this case, Hispanic and Asian) to each other we may add to the growing literature which questions the assumption that Euro-Americans represent the standard from which deviations must be characterized. Furthermore, we investigated sexual behavior using a bi-dimensional index of acculturation to assess specific effects of both heritage and mainstream cultures in Asians and Hispanics. Finally, we examined these effects in a large sample from a non-clinical subject pool (as opposed to recruited from a hospital or medical clinic setting, in which there is a bias towards over-representation of sexual problems such as dysfunction or disease) in an effort to extend our findings to the general population.

In keeping with previously discussed studies, we expected that Asian Americans would show the most conservative rates of sexual behaviors (fewest sexual experiences, fewest sexual partners, and latest sexual debut) than either Hispanic or Euro-American Americans, and that there would be comparable levels of sexual behaviors in Hispanics and Euro-Americans. We predicted that there would be gender differences in acculturation effects on sexual behavior in both Asians and Hispanics. Novel to this study, we predicted that there would be a significant interaction between heritage and mainstream acculturation in both Asian and Hispanics, and that this interaction would be different for Hispanics and Asians.

Method

Participants

A total of 1,348 undergraduate students (429 men, 919 women) at a large, public Southwestern university participated in this study for course credit in an introductory psychology course. The sample was composed of 67% Euro-American, 17% Hispanic, and 16% Asian participants. Participants ranged from 18 to 42 years old with a mean age of 19.03 for men (range, 18–32) and 18.79 for women (range, 18–42). There was no significant age difference between ethnic groups, F(2, 1,408) = 1.16. The age difference between men and women was significant, F(1, 1,408) = 2.48, p < .05. For a more detailed description of participant demographics and recruiting procedure, see Ahrold and Meston (2008).

Measures

Heritage/Acculturation

Acculturation was assessed using the Heritage and Mainstream Subscales of the Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA; Ryder et al., 2000). This self-report scale reflects two coexisting dimensions of acculturation, including the extent to which an individual identifies with their heritage of origin (Heritage subscale) and the extent of identification with North American mainstream culture (Mainstream subscale). Items have response formats of (1) disagree to (9) agree. All odd-numbered questions reflect statements endorsing identity with heritage (e.g., “I often participate in my heritage cultural traditions”), and all even-numbered questions reflect mainstream culture identification (e.g., “I believe in mainstream North American values”). Means of heritage and mainstream items were obtained and entered into analyses, with higher means indicating greater identification with each domain. Subscale means for each ethnic and gender group are presented in Table 1. The reliability of the VIA is internally consistent in cross-cultural samples for both the heritage domain (Cronbach’s α = .91–.92) and the mainstream domain (Cronbach’s α = .87–.89). Concurrent and factorial validity have also been demonstrated for the VIA (see Ryder et al., 2000). Within Asians and Hispanics, there were no significant ethnic group difference in either heritage acculturation, F(2, 480) = 2.54, p > .05 or mainstream acculturation, F(2, 480) = 3.07, p > .05. There was also no significant gender group difference in heritage or mainstream acculturation, F(1, 480) < 1.

Table 1.

Self-reported acculturation by gender and ethnicity

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic | Asian | Hispanic | Asian | |||||

| N: | 70 | 90 | 163 | 157 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Heritage | 6.76a | 1.72 | 7.13 | 1.37 | 6.81 | .68 | 7.05 | 1.63 |

| Mainstream | 7.09 | 1.40 | 7.04 | 1.14 | 7.45 | .49 | 7.08 | 1.10 |

Absolute range, 1–9

Sexuality Measures

Sexual experience was assessed using 16 items from the Experience Scale of the Derogatis Sexual Functioning Index (DSFI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1979). Four domains of sexual experience were included: petting (6 items), oral sex (5 items), intercourse (4 items), and masturbation (1 item). Participants indicated whether they had ever engaged in these sexual behaviors (yes/no response format). Sexual experience categories were coded based on whether the individual had engaged in any form of that type of sexual behavior. For example, if an individual had experienced “Mutual petting of genitals to orgasm” and/or “Kissing and petting” the individual would be coded as having petting experience (e.g., any form of petting). The DSFI Experience Scale demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .97) and high test–retest reliability (Cronbach’s α = .92). In this sample, there was acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = .67).

Four items from the Sociosexual Orientation Inventory (SOI; Simpson & Gangestad, 1991) were used to measure casual sexual behavior. Participants endorsed the number of partners they had engaged in intercourse with in their lifetime and (separately) during the past year, as well as frequency of one-time sexual encounters and projected sexual partner count over the next five years. Responses were recoded into 0, 1, 2–5, 6–10, and >11 categories for each SOI item.

Three age-of-debut items were used to measure the age at which participants first engaged in certain sexual behaviors. These included age of first sexual caress (defined as “kissing and/or petting”), age at first sexual activity (defined as “contact with partner’s genitals”), and age at first intercourse.

Procedure

Participants completed a demographics questionnaire, a sexual attitudes questionnaire, an acculturation questionnaire, as well as a number of other sexually relevant measures not reported here (see Ahrold & Meston, 2008; Meston & Buss, 2007; Meston & O’Sullivan, 2007). For procedural details, please see Ahrold and Meston (2008).

Results

Because there was a significant difference in age between men and women, age was entered as a covariate in all analyses (except age-of-debut items).

Sexual Experience

To analyze ethnic and gender differences in sexual experience, χ2 analysis was conducted on the DSFI Experience items. To adjust for a large family-wise error rate, a Bonferroni correction was applied by dividing the standard alpha level by the number of comparisons being made. Thus, results were considered statistically reliable only if they had a significance of p < .0125 (.05/4 comparisons). These results are presented in Table 2 along with corresponding percentages. There was a significant gender-by-ethnicity interaction in two categories of sexual experience: Asian men were significantly less likely to report experience in intercourse and oral sex. Across genders, while Asians were significantly less likely to report having had experience in petting, oral sex, or intercourse, Hispanics and Euro-Americans reported similar levels of sexual experience. Across ethnicities, women were significantly less likely than men to report having ever masturbated. Most effect sizes at the group level were very small or small (Φ = .01–.18); however, the effect size of masturbation (Φ = .29) was medium.

Table 2.

DSFI Sexual Experience subscales by ethnicity and gender

| Men | Women | Gender | Ethnicity | Ethnicity × Gender | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro-American | Hispanic | Asian | Euro-American | Hispanic | Asian | |||||||

| N: | 209 | 47 | 49 | 578 | 123 | 123 | ||||||

| Item | % Yes | % Yes | % Yes | % Yes | % Yes | % Yes | χ2a | Φb | χ2 | Φ | χ2 | Φ |

| Pettingc | 97 | 98 | 91 | 97 | 97 | 89 | .11 | .01 | 19.47*** | .13 | 1.89 | .01 |

| Oral sexc | 91 | 93 | 67 | 91 | 89 | 81 | .42 | .02 | 27.83*** | .16 | 35.55*** | .18 |

| Intercoursec | 73 | 73 | 49 | 76 | 71 | 66 | 1.64 | .04 | 15.05** | .11 | 2.78** | .14 |

| Masturbation | 97 | 93 | 89 | 68 | 60 | 60 | 107.20*** | .29 | 5.92 | .07 | 1.45 | .01 |

Pearson’s χ2

Nominal Φ (effect size)

Score indicates endorsement of one or more items within sexual behavior subscale

p < .0025 (.01/4 comparisons);

p < .00025

To test the effects of acculturation on sexual experience, blocked logistic regressions were conducted between acculturation subscales and DSFI sexual experience items. Each acculturation subscale was entered as a main effect in the first block and the interaction of both subscales in the second block. In Asian women, heritage acculturation significantly predicted lack of experience in masturbation (β = −.42, p < .01, R2 = .11) and oral sex (β = −.34, p < .05, R2 = .10). In Hispanic men, heritage acculturation significantly predicted lack of experience in intercourse (β = −.21, p < .05, R2 = .28). There were no significant interactions between acculturation subscales for sexual experience.

Age of Debut

For all age of sexual debut items, a multivariate linear analysis of variance was conducted. These results are presented in Table 3. As in group level analyses of sexual experience, effect sizes were very small to small . Men across ethnic groups reported a younger age of first sexual activity than women. Across genders, Asians reported significantly older ages of debut for first caress and first sexual activity, while Hispanics reported significantly earlier ages for age of first intercourse.

Table 3.

Age of sexual debut by ethnicity and gender

| Men | Women | Gender | Ethnicity | Ethnicity × Gender | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro-American | Hispanic | Asian | Euro-American | Hispanic | Asian | ||||||||||||||||

| N: | 209 | 47 | 49 | 578 | 123 | 123 | |||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F |

|

F |

|

F |

|

||||

| Age of first caress | 14.65 | 2.73 | 14.18 | 2.80 | 15.95 | 2.29 | 15.06 | 1.83 | 15.03 | 2.87 | 16.55 | 1.99 | 1.65 | .01 | 12.59*** | .04 | <1 | .01 | |||

| Age of first sexual activity | 16.08 | 1.95 | 15.68 | 1.88 | 16.56 | 1.65 | 16.60 | 1.54 | 16.44 | 2.28 | 17.17 | 1.74 | 11.05** | .02 | 4.19* | .01 | <1 | .01 | |||

| Age of first intercourse | 16.61 | 2.33 | 16.31 | 1.78 | 16.79 | 1.97 | 16.62 | 1.54 | 16.52 | 2.25 | 17.63 | 2.78 | <1 | .01 | 3.10 | .01 | <1 | .01 | |||

Partial η2 (effect size)

p < .016 (.05/3 comparisons);

p < .003;

p < .0003

To test the effects of acculturation on age of debut, blocked linear regressions were conducted between acculturation subscales and age of debut items. Each acculturation subscale was entered as a main effect in the first block and the interaction of both subscales in the second block. In Asian women, mainstream acculturation significantly predicted a younger age of first caress (β = −.57, p < .001, R2 = .16) while heritage acculturation predicted a significantly older age of first caress (β = .30, p < .01, R2 = .16). Heritage acculturation also significantly predicted an older age of first sexual activity in Asian women (β = .23, p < .05, R2 = .09). In Asian men, heritage acculturation significantly predicted older age at first sexual activity (β = .35, p < .05, R2 = .10) and age of first intercourse (β = .46, p < .05, R2 = .14). Acculturation did not significantly predict age of debut for Hispanics. As before, there were no significant interactions between acculturation subscales for age of debut.

Casual Sexual Behavior

A multivariate linear ANOVA was conducted to analyze ethnic and gender differences in SOI casual sexual behavior items (see Table 4). To adjust for a large family-wise error rate, results were considered statistically reliable only if they had a significance of p < .006 (p = .05/9). Asians reported the fewest sexual partners in the past year (F (1, 480) = 15.59, p < .006, ), and were also significantly less likely to report having one-time sexual encounters (F(1, 480) = 12.20, p < .006, ). Again, effect sizes in group level analyses were very small to small .

Table 4.

Endorsement of casual sexual behavior items (in %) by gender and ethnicity

| Item | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro-American % | Hispanic % | Asian % | Euro-American % | Hispanic % | Asian % | |

| Sexual partners (lifetime)a | ||||||

| 0 | 18 | 11 | 31 | 15 | 15 | 37 |

| 1 | 17 | 16 | 31 | 18 | 20 | 24 |

| 2–5 | 36 | 39 | 28 | 41 | 42 | 30 |

| 6–10 | 18 | 23 | 5 | 18 | 12 | 6 |

| >10 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 2 |

| Sexual partners (last year)b | ||||||

| 0 | 29 | 23 | 49 | 24 | 23 | 44 |

| 1 | 35 | 37 | 30 | 35 | 36 | 32 |

| 2–5 | 29 | 32 | 19 | 35 | 33 | 22 |

| 6–10 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| >10 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Sexual partners (anticipated)c | ||||||

| 0 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 16 |

| 1 | 22 | 23 | 43 | 32 | 36 | 50 |

| 2–5 | 43 | 48 | 41 | 49 | 49 | 28 |

| 6–10 | 17 | 13 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| >10 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| Sexual partners (once only)d | ||||||

| 0 | 42 | 35 | 72 | 46 | 43 | 70 |

| 1 | 26 | 28 | 11 | 24 | 28 | 20 |

| 2–5 | 26 | 26 | 14 | 25 | 22 | 6 |

| 6–10 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| >10 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| N | 291 | 69 | 79 | 631 | 154 | 139 |

Response to “With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse, or oral sex, in your lifetime?”

Response to “With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse, or oral sex, in the past year?”

Response to “With how many partners will you probably have sexual intercourse, or oral sex with over the next five years?”

Response to “With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse, or oral sex, on one and only one occasion?”

To test the effects of acculturation on casual sexual behavior, blocked linear regressions were conducted between acculturation subscales and SOI casual sexual behavior items. Each acculturation subscale was entered as a main effect in the first block and the interaction of both subscales in the second block.

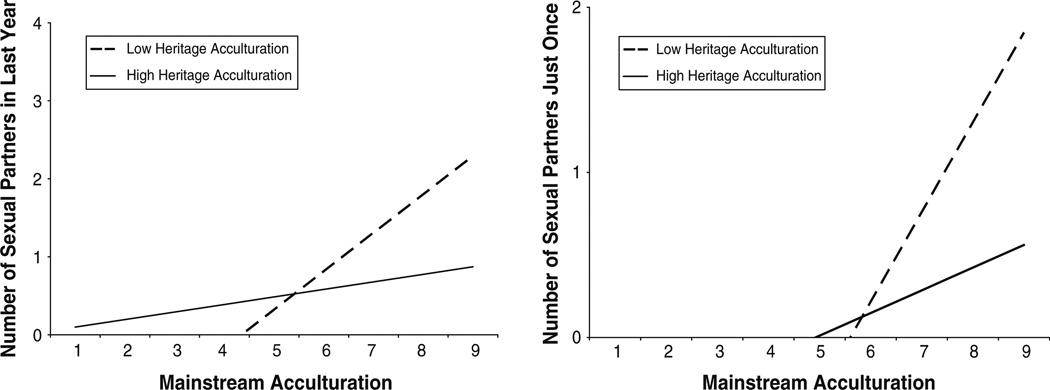

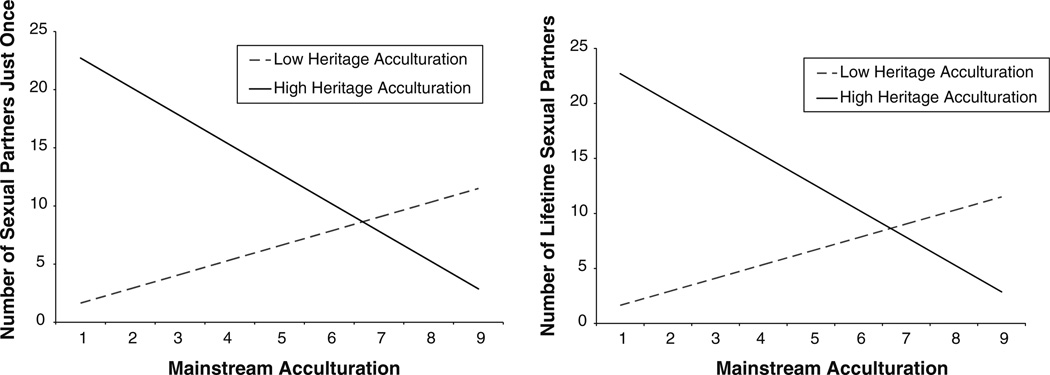

In Asian women, there was a significant interaction between heritage and mainstream acculturation in predicting partners in the last year and one-time sexual encounters, such that the relationship between heritage acculturation and casual sexual behavior was stronger at lower levels of mainstream acculturation (see Fig. 1). In Hispanic men, there was a significant interaction between heritage and mainstream acculturation in predicting one-time sexual encounters and number of lifetime partners. Namely, at low levels of heritage acculturation, there was a positive relationship between mainstream acculturation and sociosexual permissiveness; however, at high levels of heritage acculturation, there was a negative relationship between mainstream acculturation and sociosexual permissiveness (see Fig. 2). There were no significant main effects of separate acculturation subscales in predicting casual sexual behavior in Asians or Hispanics.

Fig. 1.

Interaction between mainstream and heritage acculturation in Asian women in number of partners in last year and number of one-time sexual encounters

Fig. 2.

Interaction between mainstream and heritage acculturation in Hispanic men in number of one-time encounters and lifetime sexual partners

Discussion

Consistent with hypotheses, Asian-Americans reported the most conservative sexual behaviors. Hispanics and Euro-Americans reported similar rates of sexual behaviors. Strikingly, women across all ethnic groups reported as liberal or even more liberal sexual behaviors as men. While there were several significant group level differences in sexual behavior, the effect sizes for these ethnographic comparisons ranged from very small to small. Acculturation had a stronger effect in women than men, with the strongest relationships seen in Asian women; in contrast to the ethnographic comparisons, the effect sizes for acculturation effects ranged from small to medium. There was a significant interaction between heritage and mainstream acculturation in predicting casual sexual behavior in Asian women and Hispanic men; however, these two interactions were of distinctly different types. In the case of Asian women, the best predictor of casual sexual behavior can be characterized as an “assimilation” model, while in Hispanic men, the best predictor was an “ethnogenesis” model of acculturation. Each of these findings is considered separately below.

Ethnographic and Gender Comparisons

The present study replicated previous research which indicated that Asians have lower levels of sexual behaviors than do Euro-Americans (e.g., Laumann et al., 2005; Meston et al., 1996) and compares these results to the relative level of sexual behavior in Hispanics. These findings have strong construct validity in that multiple measures of sexual behavior all pointed to conservativism on the part of the Asians in our sample. Interestingly, it was specifically Asian men who reported lower rates of sexual experience and fewer sexual partners than Asian women, Hispanics or Euro-Americans. These findings echo previous studies which have found that Asian-American women were more likely than men to be sexually experienced in kissing and petting, oral sex, and intercourse, although age of first sexual experiences do not differ significantly (Cochran, Mays, & Leung, 1991). Huang and Uba (1992) posited that this effect may be due to gender-specific ethnic stereotypes of the eroticized Asian woman and the asexual, androgynous Asian man. Moreover, it has been shown that women tend to date older, more sexually experienced men, while men of the same cohort typically date younger women (Johnson, Wadsworth, Field, Wellings, & Anderson, 1990). Thus, it is possible that the Asian women in this sample were simply exposed to more sexual opportunities by engaging with older, more experienced partners.

Hispanics reported similar levels of sexual behaviors as Euro-Americans, which is consistent with previous studies in which the variables of interest are sexual behaviors and not outcomes or consequences of risky sexual behavior (for review, see Lewis, 2004). While Hispanics reported similar levels of experience in oral sex as Euro-Americans, they also reported significantly younger age of first intercourse, lending support to the hypothesis that those Hispanics who become sexually active tend to engage in intercourse before oral sex (Driscoll et al., 2001). Similarly, the Euro-American women in this sample reported an age of first sexual activity that converged on the reported age of first intercourse, suggesting that for these women, the development of sexual repertoire is rapid after the initial sexual debut. On the other hand, Asian men and women reported distinct gaps between age of first sexual caress and first intercourse, suggesting that the development of sexual experience takes on different trajectories in different ethnic groups.

Of note were the effect sizes—ranging from very small (e.g., for ethnic differences in age of first caress) to small (e.g., Φ = .18 for ethnic by gender interaction in oral sex experience), with only one group level comparison effect size that could be described as medium (Φ = .29 for gender differences in masturbation). This implies that although many of our findings were significant in a large sample, they are not substantial at the level of the individual. Many researchers have noted that studies of sexuality at the ethnographic group level are often limited in scope as they reflect statistically significant, not important, differences. Indeed, Woo and Brotto (2008) found that there were no significant differences between East Asians and Euro-Americans in age of first intercourse at the ethnic group level, suggesting that for smaller samples, such differences may be not only unobservable but irrelevant.

Differential Effects of Acculturation in Hispanics and Asians

As noted above, there were few differences found between Euro-Americans and Hispanics in all categories of sexual behavior measured. One possible explanation of this may be that, compared to Asians, Hispanics reported relatively higher levels of identification with the mainstream culture than with the heritage culture, indicating that the Hispanics in the present sample shared similar cultural influences as Euro-Americans. However, it should be noted that even highly acculturated Asians reported more conservative rates of sexual behavior. These seemingly contradictory findings indicate that acculturation has differential effects on Asians and Hispanics.

Particularly in Asian women, it appears that differences in casual sexual behavior can be best described by an assimilation model of acculturation. Assimilation is a process in which acculturation occurs through giving up the heritage culture and adopting the mainstream culture. Differences in sexual permissiveness were seen in those Asian women who assimilated, rather than being selectively associated with exposure to the mainstream culture alone. It should be noted that this was only true for casual sexual behaviors and not for sexual experience overall. Indeed, we found that, in the case of sexual experience, endorsement of the heritage subscale alone predicted lack of experience in Asian women, rather than an interaction of the subscales. However, Brotto et al. (2005) found that endorsement of the mainstream subscale of the VIA alone predicted sexual experience in Asian women. Taken together, these findings suggest differential interactions of mainstream and heritage acculturation is possible for different categories of sexual behavior; however, further replications would be necessary to determine this.

While there were no significant effects of acculturation on the range of sexual experiences in Asian men, there was a significant effect of heritage acculturation in predicting age of sexual debut. This was true regardless of the level of mainstream acculturation, indicating that, for Asian men, heritage acculturation was an overriding factor. It is possible that for these men, heritage culture acts as a lens through which the mainstream culture is experienced—that is, an Asian man who is high in heritage acculturation may only orient himself towards those elements of the mainstream culture that support sexual values systems that are similar to those found in their heritage culture. Indeed, these findings compliment those of Brotto et al. (2007), who found that mainstream acculturation significantly predicted conservativism of sexual attitudes and information but not experience in Asian men. Taken together, these findings suggest that, for intrapersonal sexuality (e.g., sexual attitudes), acculturation to the mainstream may be more important as exposure to new perspectives change thoughts and feelings about sexuality. However, because interpersonal sexuality (e.g., sexual behaviors) relies on the environment in which the individual lives, the interpersonal context for sexual behaviors may be more influenced by the individual’s heritage acculturation.

Similar to the effects seen in Asian women, there was a significant interaction between acculturation dimensions in predicting casual sex behavior in Hispanic men: namely, at low levels of heritage acculturation, acculturation effects followed an assimilation model such that higher mainstream acculturation predicted more liberal sexual behaviors. However, at high levels of heritage acculturation, mainstream acculturation was associated with more conservative sexual behaviors. In other words, permissiveness of sexual behavior was most strongly associated with a single-dimension cultural identity (either solely mainstream or solely heritage) while conservativism of sexual behavior was associated with ethnogenesis. Ethnogenesis is a process by which acculturation occurs through a merging of heritage and mainstream cultures into a new cultural identity that is neither wholly one nor the other (Flannery, 2001). This finding has implications for interventions aimed at risky sex behaviors in Hispanic men: namely, encouraging Hispanic men to cultivate both heritage and mainstream cultural identities may act as a protecting factor against casual sex. Specifically, it is possible that for men, Hispanic-American culture discourages casual sexual behavior where both Hispanic and Euro-American cultures alone encourage such encounters under the guise of “machismo” or “manliness,” respectively.

Interestingly, acculturation was not a significant predictor of sexual behavior in Hispanic women, perhaps due to the limited variance within that subgroup. That is, because Hispanic women did not vary much in their acculturation, there was a limited range in which one could observe statistically significant effects. This, in turn, implies that dimensional acculturation measures may not be effective in capturing acculturation effects on sexual behavior in Hispanic women.

The difference in acculturation effects in Asians and Hispanics serves to illustrate that the relative context of acculturative processes are different for each group. Moreover, considering that the present sample was collected in Texas—which is close to Latin America, both physically and culturally—it is not surprising that the acculturation process would be different for Asians and Hispanics. That is, integrating and adjusting to the mainstream culture may be more straightforward for Hispanics in the present sample as Texas mainstream culture may be closer to that of most Hispanics than of most Asians. Clearly, it is important to note the differential contexts of acculturation for different ethnic groups (Ahrold, Woo, Brotto, & Meston, 2007). Moreover, even in more culturally “neutral” areas, the process of acculturation is likely to be very different for each ethnic group. It is not simply enough to measure the absolute rates of acculturation, even with a dimensional measure; one must consider the relative cultural context of the area in which these measures are taken. Both intergroup and intragroup relationships, and the attitudes that arise from these relationships, may be very different between areas of the nation, between urban and non-urban environments, or even within districts of a city.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are a few limitations to these findings that warrant consideration. Firstly, and most importantly, the present study surveyed a limited range of ages, with most participants falling into late adolescence or early adulthood. Sexual experience is, not surprisingly, linked to age (i.e., older people tend to have had more sexual experience). However, it has been shown that one of the best predictors of future sexual behavior is past sexual behavior (Newcomer & Urdy, 1988), especially in the case of adolescent behaviors predicting adult behaviors (Harvey & Spigner, 1995). Thus, these findings describe trends and gross differences that likely generalize to later life; it is unlikely that the ethnic differences noted will change dramatically later in adulthood.

The present study’s measure of acculturation (the VIA) has not been validated in Hispanic populations. However, the VIA was designed to be free from bias towards any particular heritage culture; namely, it allows the participant to define their own meaning of “heritage culture” and asks about identification with elements of culture that are common to all cultures (e.g., friends, humor, traditions). As such, there is no theoretical reason to believe that the VIA is not valid in Hispanic populations. Nevertheless these findings should perhaps be considered exploratory until the VIA has been fully validated in this population.

In general, the differences between levels of experience in men and women in the present sample were not as pronounced as has been previously reported (for review, see Alexander & Fisher, 2003), which may be due to the fact that this is an undergraduate sample; historical trends in sexual behavior suggest that college-educated women and men are converging in terms of attitudes towards sexuality and sexual experience (Thornton & Young-Demarco, 2001). It should be noted, however, that these trends may not apply to populations with less education as the sexual scripts in these populations have not changed as dramatically as those of highly educated individuals (Oliver & Hyde, 1993).

Another limitation is that of ethnic-specific biasing. It has been posited that Asians are less likely to report sexual behaviors than are Euro-Americans (Tang, Lai, Phil, & Chung, 1997). However, counter-evidence indicates that social desirability in Asian-Americans had no more effect on reports of sexuality than for Euro-American counterparts (Meston, Heiman, Trapnell, & Paulhus, 1998). Several steps were taken to prevent pressures of self-report, including complete anonymity and administration of surveys in a confidential, private setting; however, it is possible that there is some intrinsic, culturally derived bias which could not be avoided regardless of the setting. If that is the case, however, it is likely that these biases would be ever-present—thus, these findings approximate what would be found in a clinical setting. Similarly, there may have been some biasing due to self-selection of the participant sample: that is, those individuals who felt uncomfortable answering questions about their sexuality may have declined to participate. However, we would expect that the addition of these individuals would serve to further emphasize, not detract from, the differences reported in the present study.

In conclusion, the present study provides support for different models of acculturative effects which will be helpful for clinicians working with ethnically diverse populations. Specifically, it is important to note what is normative in a subpopulation for the purposes of defining pathological behavior within that population. Also, it is important for clinicians to be aware of the acculturative mechanisms which act on ethnic minority individuals so that they may counsel individual members of the same ethnic group appropriately. Clinicians working in an increasingly diverse population must note that just as culture shapes the sexuality of different ethnic groups, so acculturation may have differential effects between groups. Furthermore, identifying ethnic and acculturation differences in sexual behavior can help to provide a springboard for future studies to empirically examine the effect of culture on sexuality, both in specific ethnic groups and in the growingly diverse population of the U.S.

References

- Abramson PR, Imai-Marquez J. The Japanese–American: A cross-cultural, cross-sectional study of sex guilt. Journal of Research in Personality. 1982;16:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Afable-Munsuz A, Brindis CD. Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: A literature review. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38:208–219. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.208.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrold TK, Meston CM. Ethnic differences in sexual attitudes of U.S. college students: Gender, acculturation, and religiosity factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9406-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrold TK, Woo JS, Brotto LM, Meston CM. Acculturation effects on sexual function: Does minority group visibility matter?. Poster presented at the meeting of the International Academy of Sex Research; Vancouver, BC. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MG, Fisher TD. Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:27–35. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997;46:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 2006;55:303–332. [Google Scholar]

- Brindis C, Wolfe AL, McCarter V, Ball S, Starbuck-Morales S. The associations between immigrant status and risk-behavior patterns in Latino adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17:99–105. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00101-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto LA, Chik HM, Ryder AG, Gorzalka BB, Seal BN. Acculturation and sexual function in Asian women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2005;34:613–626. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-7909-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto LA, Woo JST, Ryder AG. Acculturation and sexual function in Canadian East Asian men. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007;4:72–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain VS, Johannes CB, Avis NE, Mohr B, Shocken M, Skurnick J, et al. Sexual functioning and practices in a multi-ethnic study of midlife women: Baseline results from SWAN. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:266–277. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Leung L. Sexual practices of heterosexual Asian-American young adults: Implications for risk of HIV infection. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1991;20:381–391. doi: 10.1007/BF01542618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The DSFI: A multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1979;5:244–281. doi: 10.1080/00926237908403732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Biggs MA, Brindis CD, Yankah E. Adolescent Latino reproductive health: A review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:255–326. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery W. An empirical comparison of acculturation models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1035–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Norris AE. Urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults: Relationship of acculturation to sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D, Piacentini J, Van Rossen R, Hien D, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Effects of acculturation and psychopathology on sexual behavior and substance use of suicidal Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1998;20:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Barreto RM. Asian American adolescents’ first sexual intercourse: Gender and acculturation differences. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38:28–36. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.028.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SM, Spigner C. Factors associated with sexual behavior among adolescents: A multivariate analysis. Adolescence. 1995;30:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Uba L. Premarital sexual behavior among Chinese college students in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1992;21:227–240. doi: 10.1007/BF01542994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Field J, Wellings K, Anderson RM. Surveying sexual attitudes. Nature. 1990;343:109. doi: 10.1038/343109a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Succop PA, Ho GYF, Burk RD. Mediators of the association between age of first sexual intercourse and subsequent human papillomavirus infection. Pediatrics. 2002;109:5–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2000;49:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser B, Paik A, Gingell C, Moreira E, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 years: Prevalence and correlates identified in the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2005;17:39–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LJ. Examining sexual health discourses in a racial/ethnic context. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33:223–234. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026622.31380.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin BV, Tschann JM, Gomez CA, Kegeles SM. Acculturation and gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic white unmarried adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:1759–1761. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.12.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Buss DM. Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:477–507. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Heiman JR, Trapnell PD, Paulhus DL. Socially desirable responding and sexuality self-reports. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, O’Sullivan LF. Such a tease: Intentional sexual provocation within heterosexual interactions. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:531–542. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Trapnell PD, Gorzalka BB. Ethnic and gender differences in sexuality: Variations in sexual behavior between Asian and non-Asian university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1996;25:33–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02437906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Trapnell PD, Gorzalka BB. Ethnic, gender, and length-of-residency influences on sexual knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer D, Udry JR. Adolescent’s honesty in a study of sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1988;3:419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki S. Influences of culture on Asian Americans’ sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:34–41. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MB, Hyde JS. Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:29–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orshan SA. Acculturation, perceived social support, self-esteem, and pregnancy status among Dominican adolescents. Health Care for Women International. 1999;20:245–257. doi: 10.1080/073993399245746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM. Acculturation: Theory, models, and some new findings. In: Portes A, editor. The new second generation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1980. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Zamboanga BL, Carlo G. Acculturation status and sexuality among female Cuban American college students. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:7–13. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.1.7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Perez-Stable EJ, Otero-Sabogal R, Hiatt RA. Gender, ethnic, and acculturation differences in sexual behaviors: Hispanic and non-Hispanic white adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Gangestad SW. Individual differences in sociosexuality: Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:870–883. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Ethnic minority issues in psychology: A reexamination. American Psychologist. 1983;38:583–592. [Google Scholar]

- Tang CS, Lai FD, Phil M, Chung TKH. Assessment of sexual functioning for Chinese college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1997;26:79–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1024525504298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Young-DeMarco L. Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1009–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Flores E, Marin BV, Pasch LA, Baisch EM, Wibbelsman CJ. Interparental conflict and risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents: A cognitive-emotional model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:373–385. doi: 10.1023/a:1015718008205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau Population Division. [Retrieved 7 March 2008];2008 http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/006808.html.

- Upchurch DM, Aneshensel CS, Mudgal J, McNeely CS. Sociocultural contexts of time to first sex among Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1158–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Rieger D, Quintana D. Comparative acculturation of Southeast Asian and Hispanic immigrants and sojourners. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1987;18:345–362. [Google Scholar]

- Woo JST, Brotto LA. Age of first sexual intercourse and acculturation: Effects on adult sexual responding. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5:571–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PM. Asian American adolescents and the stress of acculturation: Differences in gender and generational levels. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2006;66:3183. [Google Scholar]