Background: The mechanisms for recruiting and activating deubiquitinase(s) during GPCR trafficking are unknown.

Results: PKA phosphorylation of USP20 Ser-333 inhibits β2AR interaction as well as deubiquitination and promotes receptor degradation via autolysosomes during physiological stress.

Conclusion: USP20 activity and substrate-specific interaction involves a phosphorylation code.

Significance: We identify a novel role for PKA in USP20 regulation and ubiquitin-dependent sorting of GPCRs.

Keywords: Adrenergic Receptor, Autophagy, Deubiquitylation (Deubiquitination), PKA, Ubiquitylation (Ubiquitination), USP20

Abstract

Ubiquitination by the E3 ligase Nedd4 and deubiquitination by the deubiquitinases USP20 and USP33 have been shown to regulate the lysosomal trafficking and recycling of agonist-activated β2 adrenergic receptors (β2ARs). In this work, we demonstrate that, in cells subjected to physiological stress by nutrient starvation, agonist-activated ubiquitinated β2ARs traffic to autophagosomes to colocalize with the autophagy marker protein LC3-II. Furthermore, this trafficking is synchronized by dynamic posttranslational modifications of USP20 that, in turn, are induced in a β2AR-dependent manner. Upon β2AR activation, a specific isoform of the second messenger cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKAα) rapidly phosphorylates USP20 on serine 333 located in its unique insertion domain. This phosphorylation of USP20 correlates with a characteristic SDS-PAGE mobility shift of the protein, blocks its deubiquitinase activity, promotes its dissociation from the activated β2AR complex, and facilitates trafficking of the ubiquitinated β2AR to autophagosomes, which fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes where receptors are degraded. Dephosphorylation of USP20 has reciprocal effects and blocks trafficking of the β2AR to autophagosomes while promoting plasma membrane recycling of internalized β2ARs. Our findings reveal a dynamic regulation of USP20 by site-specific phosphorylation as well as the interdependence of signal transduction and trafficking pathways in balancing adrenergic stimulation and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Introduction

β-Adrenergic receptor (βAR)3 signaling activates Gs-coupled adenylyl cyclase, leading to the production of cAMP, which activates protein kinase A (PKA), a major signaling kinase that modulates cell responses (1). When continuously or repeatedly subjected to agonist stimulation, βARs cease signal transduction and lose the ability to stimulate G protein effector pathways. This failure to provoke a cellular response is referred to as receptor desensitization (2). Acute desensitization results from a two-step regulatory mechanism. First, G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) phosphorylate agonist-activated receptors. Second, the phosphorylated receptor recruits and binds to adaptor proteins, β-arrestins (isoforms 1 and 2), which interdict receptor/G protein coupling (3, 4). On the other hand, long-term desensitization of βAR signaling requires degradation of cell surface receptors in the intracellular compartments called lysosomes (5–10). Prolonged desensitization as well as down-regulation of βARs is a hallmark of human heart failure (11, 12). The key factors that promote βAR down-regulation in failing hearts remain unclear.

A posttranslational modification called ubiquitination, discovered originally as a tag for proteasomal degradation, is now widely accepted as a sorting signal during vesicular trafficking of internalized cell surface receptors (10, 13–15). Agonist-stimulated ubiquitination of mammalian GPCRs was first described for the β2AR and the chemokine CXCR4 (16, 17). For these receptors, ubiquitination has been shown to be a tag for post-endocytic lysosomal targeting and receptor degradation. Currently this is one of the main mechanisms required for the regulation of the life cycle of GPCRs and other cell surface receptors (10, 18). Ubiquitination of the β2AR not only requires agonist stimulation but also phosphorylation of the receptor by GRKs and association with β-arrestin2, which functions as an adaptor to link the ubiquitinating enzymatic machinery to the activated receptor complex (16). β-arrestin2 acts as an adaptor for the HECT (homology to E6-AP carboxyl terminus) domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4, which ubiquitinates the β2AR and regulates lysosomal degradation of the receptor (19, 20). Additionally, the deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) USP20 and USP33 reverse ubiquitination and divert the internalized β2ARs to a recycling pathway (21, 22). Accordingly, ubiquitination and deubiquitination of the activated β2AR facilitated by specific enzymes define the extent and revival of adrenergic signaling at the plasma membrane.

We discovered a novel mechanism by which the DUB activity of USP20 is regulated by the signaling kinase PKA, which promotes the trafficking of ubiquitinated β2ARs to autophagosomes and, subsequently, to the lysosomes, effecting degradation and prolonged desensitization. Although studies have historically shown GPCR trafficking to lysosomes, there has been little evidence of the trafficking of GPCR complexes into autophagic vesicles. Here we visualize the specific colocalization of internalized β2ARs and the autophagy marker LC3-II (23), and we further demonstrate a link between this colocalization and USP20 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

The antibodies used for our studies included anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma, catalog no. F3165), anti-HA 12CA5 (Roche, catalog no. 11666606001), anti-HA probe (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-805), anti-LC3 (Novus, catalog no. NB100-2220), anti-LC3A (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4599), anti-ubiquitin FK1 (Enzo Life Sciences, catalog no. BML-PW8805), anti-β2AR H20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-569), anti-USP20 (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A301-189A), anti-PKAα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-903), anti-PKAβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-904), anti-LAMP2 H4B4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-18822), anti-Actin, anti-GAPDH-HRP (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 3683), and anti-Ser(P)/Thr(P) (ECM Biosciences, catalog no. PP2551). The custom antibody that specifically detects Ser(P)-333, USP20, was produced by GenScript. Alexa Fluor 488-, 594-, and 633-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from GE/Amersham Biosciences or Rockland Immunochemicals.

Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma, catalog no. A2220), Anti-HA-agarose (Sigma, catalog no. E6779), protein G Plus/protein A-agarose (Calbiochem, catalog no. IP10), (−)-isoproterenol (Sigma, catalog no. I2760), propranolol, ICI-118,551, N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma, catalog no. E1271), Triton X-100 (Sigma, catalog no. T-9284), recombinant PKAα, 1,9-dideoxy forskolin (Calbiochem, catalog no. 344277), Forskolin (Calbiochem, catalog no. 344270), bafilomycin A1 (Cayman, catalog no. 11038), MG132 (Sigma, catalog no. C2211), chloroquine (MP Biomedicals, catalog no. 193919); SUMO-1 vinyl sulfone or SUMO-1-VS (Boston Biochem, catalog no. UL-702), NEDD8-VS (Boston Biochem, catalog no. UL-802), and (−)iodocyanopindolol [125I] (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, catalog no. NEX189) were used in our studies.

Plasmids

The USP20 plasmid used in these studies has been described previously (21). An HA epitope tag was added to the amino terminus or carboxyl terminus of human full-length USP20 cDNA and to the amino terminus of the truncated forms of human USP20, and each construct was subcloned into pcDNA3.0 using standard protocols. Amino acid residues in human HA-USP20 identified by bioinformatics searches to be sites for post-translational modification were mutated using the QuikChange Lightning or multisite-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA), and the mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. pEGFP-LC3 was provided by Dr. Finkel (Addgene) (24).

siRNA

Double-stranded siRNA oligonucleotides with 21- or 19- nucleotide duplex RNA and two-nucleotide 3′-dTdT overhangs were chemically synthesized (Dharmacon GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in a deprotected desalted form and used in various assays. Sequences of siRNA oligonucleotides were as follows: control non-targeting sequence, 5′-AAUUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′; PKAα (human), 5′-CGUCCUGACCUUUGAGUAU-3′; and PKAβ (human), 5′-GGUCACAGACUUUGGGUUU-3′.

For siRNA experiments, early-passage HEK293 cells on 100-mm dishes that were at 40–50% confluence were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent. Forty-eight hours later, cells were processed for further assays.

Cell Culture and Transfections

HEK293 and COS-7 cells were purchased from the ATCC and maintained in minimal Eagle's medium (MEM) or DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) or FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). HEK293 cells stably transfected with FLAG-β2AR and FLAG-β2AR-mYFP used in these studies have been described previously (21). S49 cell lines, WT, and Kin− (which lack activation of the catalytic subunit of PKA) were gifts from Dr. Paul A. Insel (Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego). S49 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated horse serum and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator containing 10% CO2 at 37 °C. Rat vascular smooth muscle cells were isolated and maintained as reported before (22); animal procedures were according to protocols approved by Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

48h post-transfection, cells were starved for 1 h in serum-free medium or in Hanks' balanced salt solution and stimulated in the same medium with isoproterenol for the desired time. Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and lysed in an ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mm EDTA, 250 mm NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin (5 μg/ml), aprotinin (5 μg/ml), pepstatin A (1 μg/ml), and benzaminidine (100 μm) (Sigma)). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, protein concentrations were determined by Bradford protein assay, and equivalent protein was used for immunoblotting or immunoprecipitation. For immunoprecipitations, soluble cell extracts were mixed with anti-FLAG M2 resin or anti-HA-agarose beads, and then the sample was incubated at 4 °C with end-over-end rotation overnight. Immunocomplexes were washed extensively with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer to remove nonspecific binding, and bound protein was eluted in 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. For immunoblotting, protein samples were resolved by 4–20% gradient gels or 10% gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Separation of the two USP20 bands required modified gel conditions: 60 min run with higher current (50 mA constant per minigel). Membranes were blocked in TTBS (10 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, and 2% Tween 20) supplemented with 5% (w/v) dried skim milk powder. Primary and secondary antibody incubations were performed in blocking solution, and washes were performed using TTBS. Immunoreactive bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico Reagent, Pierce). Signals were detected and acquired with a charge-coupled device camera system (Bio-Rad Chemidoc-XRS) and analyzed with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Imaging

HEK293 cells with stable transfection of FLAG-β2AR-mYFP or FLAG-β2AR were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0, HA-USP20 wild-type, HA-USP20-S333A, HA-USP20-S333D, or pEGFP-LC3. 24 h after transfection, cells were seeded on poly-d-lysine or collagen-coated 35-mm glass bottom plates. 48 h post-transfection, cells were starved for 1 h in serum-free medium or Hanks' balanced salt solution, stimulated in the same medium with 1 μm isoproterenol, fixed with 5% formaldehyde diluted in Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) containing calcium and magnesium, and then washed three times with DPBS. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100 in DPBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin for 20–30 min and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The next day, cells were washed three times with DPBS and incubated with the respective secondary antibody. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM510 laser-scanning microscope using a 100 × 1.3 oil immersion objective, and the pinhole was set to 1.0 Airy units for single fluorophore imaging. To obtain multichannel acquisition, we utilized the filter settings as multitrack sequential excitation (488, 568, and 633 nm) and emission (515–540 nm, GFP; 585–615 nm, Texas Red; 650 nm, Alexa Fluor 633). All confocal analyses were performed on samples from three to five independent experiments. In each experiment, several cells or groups of cells were analyzed. Image acquisition used the LSM 510 operating software and images were later exported as TIFF files. Further processing (resizing, addition of text, etc.) was performed using Adobe Photoshop software (CS2), and any change in brightness/contrast was applied to the entire image. Pearson's correlation coefficients for quantification of β2AR/LAMP2 or β2AR/GFP-LC3 colocalizations were performed in ≥20 cells from multiple independent experiments using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

In Vitro Translation

In vitro translation was carried out using a TnT quick-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega) along with TranscendTM chemiluminescent translation detection system components (Promega) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The in vitro synthesized proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting.

In Vitro Phosphorylation

Purified protein was mixed without or with recombinant full-length PKAα enzyme (EMD Millipore) and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS sample buffer, and the samples were analyzed by immunoblotting.

In Vitro Labeling with Chemically Activated Ubiquitin, SUMO, and Nedd8

Ubiquitin-VS labeling has been described previously (26, 27). Purified HA-USP20 protein or COS-7 lysate (overexpressed HA-USP20) was labeled with Ub-VS in different doses or a 5- to 10-fold excess of Nedd8-VS or SUMO-VS and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mm DTT. The reactions were terminated by the addition of SDS sample buffer and boiling. The samples were resolved on a Tris-glycine 10% polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen), and protein bands were detected by immunoblotting.

Receptor Degradation

The β-adrenergic receptor degradation assay was performed with radiolabeled [125I]-(−) iodocyanopindolol using methods described previously (21). Following preincubation without or with agonist, cells were washed with ice cold phosphate-buffered saline and collected in MEM supplemented with 10 mm HEPES (pH7.5) and 5 mm MgCl2. Cells were resuspended thoroughly using a 1-ml U-100 insulin syringe, and protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. Whole cell membranes were diluted in assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2 mm EDTA, 12.5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm ascorbic acid) and added to deep 96-well plates in triplicates. [125I]-(−) iodocyanopindolol was added at a final concentration of 200–400 pm in the presence or absence of the hydrophobic antagonist propranolol (10 μm, to define nonspecific binding) in assay buffer, added to the samples, and then incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. Radiolabeled membranes were collected on a Brandel harvester (Whatman GF/B glass filters briefly wetted with distilled water) and quickly washed three times with ice-cold wash buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2 mm EDTA, and 12.5 mm MgCl2). The filters were placed in plastic tubes and counted in a γ counter. The receptor density (total specific [125I]-(−) iodocyanopindolol binding sites) was determined after 24 h of Iso treatment and expressed as the percent of receptor number assessed in nonstimulated cells.

Experimental Repeats and Statistical Analyses

All Western blots and confocal experiments show representative data from one of three or more independent experiments. All quantifications shown are mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. To determine significance, results were compared with control condition by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for all bar graphs with more than two groups. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (version 6, GraphPad). p < 0.05 at a 95% confidence level was considered significant.

RESULTS

βAR Agonists Induce Dynamic Posttranslational Modifications of USP20

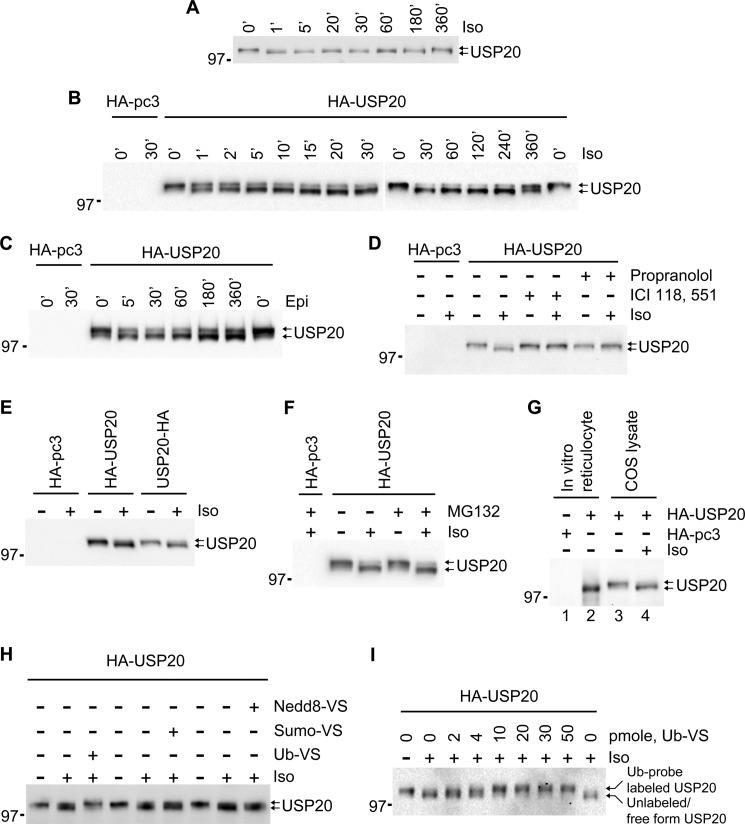

Agonist-activation of βARs in HEK293 cells or in COS-7 cells alters the electrophoretic mobility of endogenous USP20 as well as transfected HA-tagged USP20 so that a lower band with faster mobility predominates (Fig. 1, A–C). This agonist-stimulated protein mobility shift is completely blocked by βAR antagonists, namely, propranolol and ICI-118,557 (Fig. 1D). The mobility shift could not be attributed to protein processing or protein degradation because blocking the carboxyl terminus of USP20 with a HA epitope tag or inhibiting 26 S proteasomes, which can partially clip proteins (25), had no effect (Fig. 1, E and F). In vitro translation of HA-USP20 in a cell-free system revealed that the nascent protein synthesized in cells corresponds to the lower band, suggesting the upper band to be posttranslationally modified (Fig. 1G). We estimated a size difference of 10–15 kDa between the two bands. Such a shift can occur by linkage of small molecular weight proteins, namely ubiquitin (Ub) and ubiquitin-like modifiers (such as SUMO and Nedd8) that are commonly appended to other proteins. We therefore compared these small modifiers, utilizing their chemically activated forms for their ability to modify USP20 (26, 27). Only modified Ub reversed the mobility of the endogenous USP20 lower band and converted it into the upper band present in quiescent cells (Fig. 1, H and I). As discussed in the following sections, this mobility shift of USP20 is correlated with its site-specific phosphorylation and deubiquitination of the β2AR.

FIGURE 1.

Agonist-stimulated protein mobility shift of USP20. A, HEK293 cells stably transfected with FLAG-β2AR were serum-starved for 60 min. After starvation, the cells were stimulated with 100 nm isoproterenol for the indicated times and then lysed and immunoblotted with USP20 antibody. B, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0 or HA-USP20, and the endogenous β2ARs were stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol for the indicated times, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody to HA. C, COS-7 cells were transfected as in B, and the endogenous βARs were stimulated with 1 μm epinephrine (Epi) for the indicated times, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody to HA. D, COS-7 cells were transfected as in B and pretreated with β-blockers (10 μm propranolol and 20 μm ICI-118,551). The cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody to HA. E, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0, HA-USP20, or USP20-HA, and the endogenous β2ARs were stimulated with isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with HA antibody. F, COS-7 cells were transfected as in B and pretreated without or with 10 μm MG132. The cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted. G, in vitro translation was carried out using a TnT-coupled reticulocyte lysates system and the indicated plasmids. SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to the reaction products, and immunoblotting was performed using antibody to HA (lanes 1 and 2). Lanes 3 and 4 show COS-7 cells transfected with HA-USP20, stimulated with isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with HA antibody. H, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-USP20, left unstimulated or stimulated with isoproterenol and lysed, and crude cell lysates were labeled with Ub-VS, SUMO-VS, or Nedd8-VS, followed by immunoblotting with HA antibody. I, Ub-VS labeling was performed as in H, but with increasing concentrations as indicated.

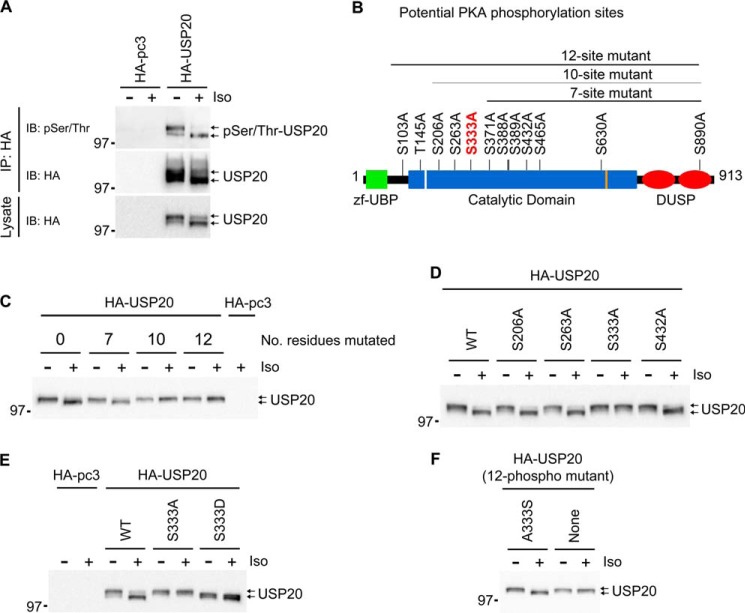

Biochemical analyses revealed that USP20 is phosphorylated. When immunoprecipitated HA-USP20 was immunoblotted with a generic anti-Ser(P)/Thr(P) antibody, both upper and lower bands were detected as phosphorylated species (Fig. 2A). Bioinformatics analyses of USP20 predicted many serines and threonines as phosphorylation sites targeted by different kinases, of which we prioritized a list of sites specific for either PKA or GRK (Figs. 2B and 3, A and B), mainly because these kinases are rapidly activated after βAR stimulation. Mutation of 10 or 12 of the PKA sites in USP20 to alanines, surprisingly blocked the agonist-induced mobility shift of USP20. However, a seven-site mutant construct still displayed the shift (Fig. 2, B and C). Subsequent single-site mutagenesis targeting the three residues that are mutated in the 10-site but not the seven-site mutant revealed that phosphorylation of serine 333 is critical for the agonist-induced mobility shift of USP20. Mutation of serine 333 to alanine prevented the shift, whereas mutation to aspartate caused a constitutive shift (Fig. 2, D and E). Furthermore, restoration of serine 333 into the 12 PKA site mutant construct (USP20 A333S) recovered the agonist-induced mobility shift of USP20 (Fig. 2F). Mutation of predicted GRK phosphorylation sites had no effect on USP20 protein mobility shift (Fig. 3, A–D). Notably, elimination of phosphorylation at serine 333 had little effect on the overall phosphorylation status of USP20, suggesting that this mutation did not compromise USP20 protein folding or structure (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 2.

Analyses of PKA phosphorylation sites in USP20. A, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0 or HA-USP20 and left unstimulated or stimulated with isoproterenol. HA-USP20 was immunoprecipitated with HA-agarose beads, and the presence of the phosphorylated form in the immunoprecipitates (IP) was detected with a Ser(P)/Thr(P)-specific antibody. B, the functional domains of USP20 are indicated. Potential PKA phosphorylation sites within the human USP20 sequence as predicted by bioinformatics are indicated. zf-UBP, zinc finger ubiquitin-specific protease domain; DUSP, domain in ubiquitin-specific protease. C–E, COS-7 cells were transfected with the HA-USP20 wild type or indicated mutant plasmids, stimulated with isoproterenol, and lysed, and cell lysates were immunoblotted with HA antibody. F, COS-7 cells were transfected with the HA-USP20–12 PKA phosphorylation mutant in which serine 333 was restored (A333S) or the HA-USP20–12 phosphomutant (all 12 PKA phosphorylation sites mutated). Transfected cells were stimulated with isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with HA antibody.

FIGURE 3.

Analyses of GRK phosphorylation sites in USP20. A and B, schematic representation of human USP20 showing putative phosphorylation target residues by GRKs that were mutated to alanine to generate HA-USP20 mutants as indicated. zf-UBP, zinc finger ubiquitin-specific protease domain; DUSP, domain in ubiquitin-specific protease. C and D, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0, HA-USP20, or indicated HA-USP20 mutant plasmids. Endogenous β2ARs were stimulated without or with 1 μm isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody to HA. E, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0, HA-USP20, or HA-USP20-S333A and were then stimulated with isoproterenol or left unstimulated. HA-USP20 was immunoprecipitated with HA-agarose beads, and the presence of phosphorylated forms in the immunoprecipitates (IP) was detected with a Ser(P)/Thr(P)-specific antibody (top panel). The levels of USP20 were detected in both immunoprecipitates (center panel) and lysates (bottom panel) using HA antibody.

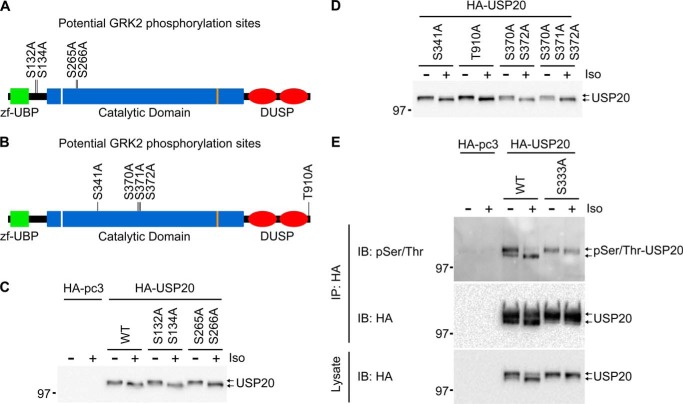

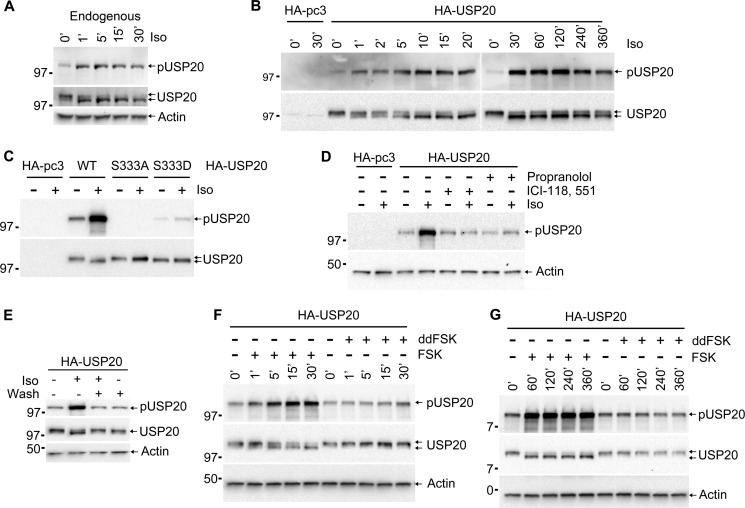

To determine whether serine 333 in USP20 is indeed phosphorylated in vivo and whether this is provoked by βAR agonists, we generated a custom anti-Ser(P)-333 antibody (pUSP20) using the 12-amino acid phosphorylation domain (Asp-Arg-Lys-Phe-Ser(P)-Trp-Gly-Glu-Glu-Arg-Thr-Asn) as the peptide antigen. This antibody detected Iso-induced phosphorylation of endogenous USP20 and exogenously expressed HA-USP20 (Fig. 4, A and B). On the other hand, the pUSP20 antibody did not detect HA-USP20 S333A or only weakly detected HA-USP20 S333D, although all of these constructs were expressed at similar levels as the wild-type HA-USP20 (Fig. 4C). βAR antagonists blocked the agonist-induced serine 333 phosphorylation just as they blocked its mobility shift (Figs. 1D and 4D). Furthermore, conditions that are known to induce membrane recycling of internalized receptors, namely removal and repeated washouts of agonists (21, 28), not only dephosphorylated USP20 serine 333 but also reversed the agonist-induced mobility shift of USP20 (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation of USP20 at serine 333 is induced by isoproterenol and forskolin. A, HEK293 cells stably transfected with FLAG-β2AR were serum-starved for 60 min. After starvation, the cells were stimulated with 100 nm isoproterenol for the indicated times, lysed, and immunoblotted with pUSP20 (top panel), USP20 antibody (center panel), and β-actin (bottom panel). B and C, COS-7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and the endogenous β2ARs were stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody specific to phospho-USP20 (pUSP20). The same blot was stripped and sequentially reprobed with antibody to HA (bottom panel). D, COS-7 cells transfected with HA-pc3 or HA-USP20 were pretreated with β-blockers (10 μm propranolol or 20 μm ICI-118551). The cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with isoproterenol, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody to pUSP20 and β-actin. E, cells were stimulated with 100 nm isoproterenol as in A with or without agonist washout as reported before (21) and then lysed and immunoblotted with pUSP20 (top panel) and USP20 antibody (center panel) and β-actin (bottom panel). F and G, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0 or HA-USP20 and stimulated with forskolin (FSK) or 1,9-dideoxy forskolin (ddFSK) for the indicated times, lysed, and immunoblotted with antibody to pUSP20, HA (for USP20), and β-actin.

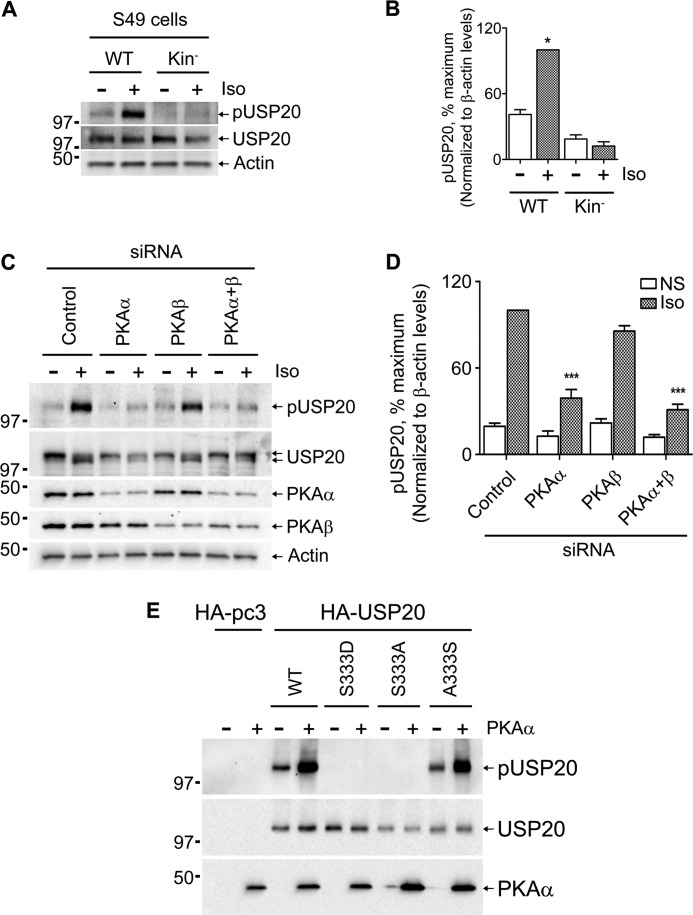

Forskolin, which directly activates adenylyl cyclase and increases cellular cAMP, also induced USP20 serine 333 phosphorylation and mobility shift, whereas the inactive analog dideoxy forskolin did not lead to these effects (Fig. 4, F and G). Previous studies have shown that cAMP signaling is impaired in mutant S49 lymphoma cells, which express a defective PKA regulatory subunit (29, 30). Correlating with the cAMP dependence, Iso-induced seryl 333 phosphorylation of USP20 is detectable in wild-type S49 lymphoma cells but not in PKA-defective cells (Fig. 5, A and B). Most cells including HEK293 cells, typically express the α and β isoforms of the PKA catalytic subunit. To define whether one or both these isoforms can phosphorylate USP20, we resorted to siRNA transfections to down-regulate individual PKA subunits. USP20 serine 333 phosphorylation was blocked upon siRNA-mediated knockdown of PKAα in HEK293 cells, whereas knockdown of PKAβ had no significant effect (Fig. 5, C and D). We further confirmed that USP20 is a direct substrate for PKA phosphorylation by performing in vitro phosphorylation assays with purified proteins. As shown in Fig. 5E, purified PKAα phosphorylated WT and serine 333 put back 12 phosphosite mutant (USP20 A333S) but not S333A or S333D constructs. On the basis of these data, we conclude that, upon βAR agonist-stimulation, activated PKAα rapidly phosphorylates USP20 specifically at serine 333 and that USP20 dephosphorylation could correlate with agonist removal and receptor recycling.

FIGURE 5.

USP20 is phosphorylated by PKAα at serine 333. A, WT and Kin− S49 mouse lymphoma cells were stimulated with 100 nm isoproterenol for 2 min, lysed, and analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated. B, quantification of pUSP20 in S49 cells from three independent experiments where maximal phosphorylation is 100%. C, HEK293 cells with stable FLAG-β2AR were transiently transfected with siRNAs targeting no known mRNA (Control), PKAα, PKAβ, or a combination of PKAα and PKAβ for 48 h. Cells were serum-starved for 60 min. After starvation, cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with 100 nm isoproterenol for 2 min, lysed, and serially immunoblotted as indicated. D, pUSP20 levels in each sample from C were quantified, and the mean data from seven to eight experiments are shown. ***, p < 0.001; NS, not significant; one-way ANOVA. E, in vitro phosphorylation was carried out using purified proteins as indicated and in the presence or absence of the recombinant PKAα catalytic subunit. SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to the reaction products and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting and analyzed using antibodies against pUSP20, HA (for USP20), and PKAα.

β2AR Deubiquitination by USP20 Is Regulated by Phosphorylation of Serine 333

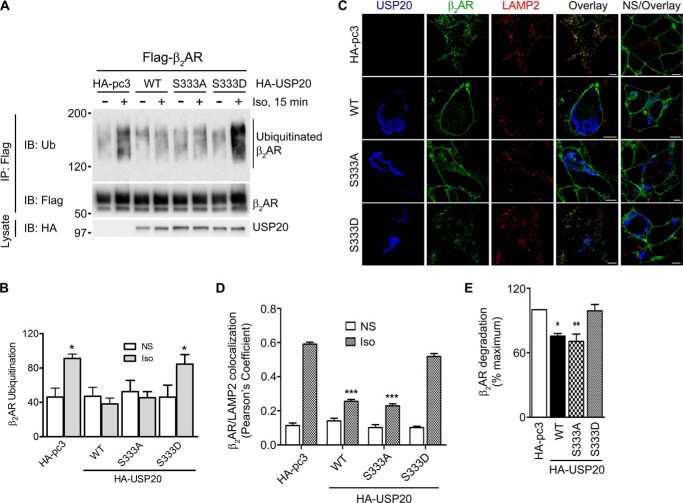

We demonstrated previously that overexpressed USP20 reverses agonist-induced ubiquitination and lysosomal trafficking of the β2AR, whereas a USP20 mutant lacking deubiquitinase activity does not promote these effects (21). To ascertain whether serine 333 phosphorylation affects the deubiquitinase functions of USP20, we overexpressed WT, S333A, or S333D constructs in HEK293 cells stably transfected with FLAG-β2AR and analyzed isoproterenol-induced ubiquitination of the receptor. In the absence of exogenous USP20, isoproterenol stimulation produced robust β2AR ubiquitination. However, either wild-type USP20 or S333A overexpression led to deubiquitination of the receptor (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, S333D overexpression did not lead to receptor deubiquitination. Overexpression of USP20 wild-type or S333A significantly decreased the colocalization of β2ARs with the lysosomal marker protein LAMP2 and also significantly blocked degradation of β2ARs, as assessed by radioligand binding (Fig. 6, C–E). In contrast, overexpression of the USP20 S333D mutant, which did not reverse ubiquitination of the β2AR (Fig. 6, A and B) did not block either lysosomal trafficking or degradation of the β2AR (Fig. 6, C–E).

FIGURE 6.

Serine 333 phosphorylation blocks USP20 activity and promotes β2AR ubiquitination, lysosomal trafficking, and degradation. A, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR-mYFP were transiently transfected with HA-pcDNA3. 0, HA-USP20-WT, HA-USP20-S333A, or HA-USP20-S333D and stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol for 15 min. The receptors were isolated with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies specific to ubiquitin (FK1) and FLAG (M2). Center panel, the amounts of receptor as detected by a FLAG antibody (M2). Bottom panel, the expression levels of USP20-WT or mutants in the lysates as detected by a HA antibody. B, ubiquitin smears in each lane from the blot in A were quantified, normalized to β2AR signals, and plotted as bars. Significant differences between HA-pcDNA3.0 and HA-USP20-WT, HA-USP20-S333A, or HA-USP20-S333D in isoproterenol-stimulated lanes were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. *, p < 0.05 HA-pc3 or HA-USP20-S333D versus HA-USP20-WT and HA-USP20-S333A; NS, not stimulated. Data are mean ± S.E. of five independent experiments. C, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR-mYFP were transiently transfected as in A and stimulated with vehicle (nonstimulated) or Iso for 6 h. Cells were then fixed and immunostained with anti-LAMP2 and anti-USP20. Confocal images are shown with FLAG-β2AR-mYFP in green, LAMP2 in red (Alexa Fluor 594), and USP20 in blue (Alexa Fluor 633). Scale bar = 10 μm. Images shown are from one of four independent experiments. D, quantification of colocalization in merged images for the two channels β2AR (green) and LAMP2 (red) in each sample (Pearson's coefficient). Significant differences between HA-pcDNA3.0 and HA-USP20-WT, HA-USP20-S333A, or HA-USP20-S333D under isoproterenol-stimulated conditions were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. ***, p < 0.001 HA-pc3 versus HA-USP20-WT or HA-USP20-S333A. E, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids and stimulated with 10 μm isoproterenol for 24 h. After stimulation, β2AR density was determined by [125I]-(−) iodocyanopindolol binding. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Data represent mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments containing duplicate samples for each condition.

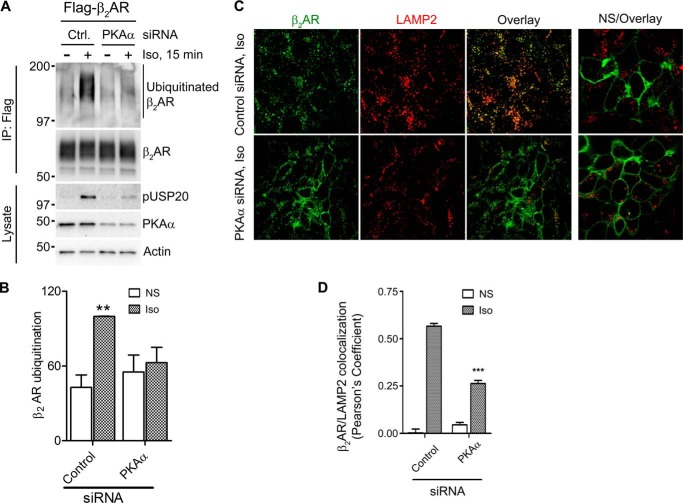

Congruent to these effects, siRNA mediated knockdown of PKAα, which blocks USP20 serine 333 phosphorylation, also blocked (i.e. reversed) β2AR ubiquitination (Fig. 7, A and B). Down-regulation of PKAα also significantly decreased colocalization of β2AR and the lysosomal marker protein LAMP2 (Fig. 7, C and D). Accordingly, serine 333 phosphorylation blocks USP20 deubiquitinase activity, whereas dephosphorylation facilitates it. β2AR lysosomal trafficking is regulated by ubiquitin tags on the receptor (21, 22, 31), and the conditions that prevented β2AR ubiquitination, namely, (a) overexpression of USP20 wild-type and S333A constructs and (b) down-regulation of PKAα, significantly decreased colocalization of β2AR and the lysosomal marker protein LAMP2.

FIGURE 7.

Knockdown of PKAα promotes β2AR deubiquitination and lysosomal trafficking. A, HEK293 cells with stable FLAG-β2AR were transiently transfected with siRNAs targeting no mRNA (Ctrl) or PKAα for 48 h, serum-starved for 60 min, and then left unstimulated or stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol for 15 min. The receptor was immunoprecipitated (IP) with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel, and the ubiquitinated β2AR was detected with an anti-ubiquitin antibody, FK1. The amounts of FLAG-tagged β2AR are shown. Lysates from control or PKAα siRNA-transfected cells were immunoblotted and analyzed using antibodies against pUSP20, PKAα, and β-actin. B, ubiquitin smears in each lane from the blot in A were quantified, normalized to β2AR signals, and plotted as bars. Significant differences between control versus PKAα siRNA-transfected cells in isoproterenol-stimulated lanes were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. **, p < 0.01; Ctrl-Iso versus Ctrl-NS as well as PKAα siRNA samples. Data are mean ± S.E. of five independent experiments. NS, not stimulated. C, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR-mYFP were transiently transfected with siRNAs targeting a generic sequence that does not correspond to known mRNA (Ctrl) or PKAα for 48 h, serum-starved for 60 min, and stimulated with vehicle (nonstimulated) or Iso for 6 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained for LAMP2 (red). Confocal images are shown with FLAG-β2AR-mYFP in green and LAMP2 in red (Alexa Fluor 594). Scale bar = 10 μm. D, Pearson's correlation coefficients calculated for β2AR and LAMP2 colocalization (mean ± S.E.) in the respective cells for isoproterenol-stimulated and non-stimulated conditions. ***, p < 0.001; control versus PKAα siRNA, one-way ANOVA.

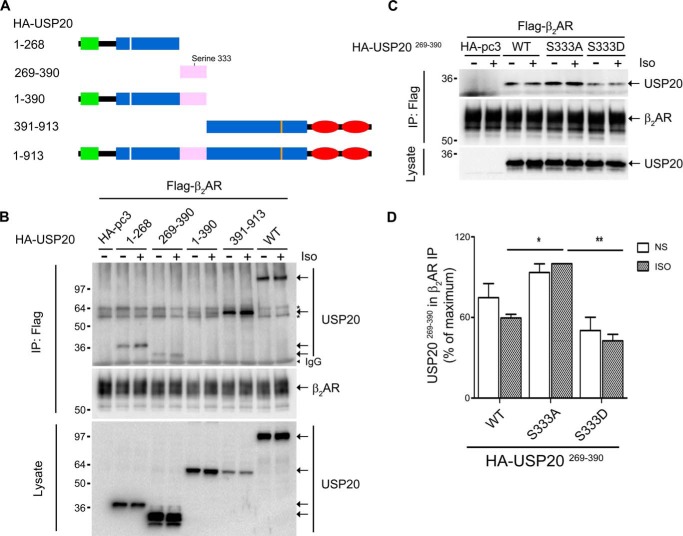

The above data suggest that the DUB activity of USP20 is closely linked to its phosphorylation status at serine 333. This site is located in the central domain of USP20 comprising a stretch of about 200 amino acids referred to as the “insertion domain,” which is a variable region found in a subset of the USP family proteins (32). Interestingly, USP20 differs considerably from its close homolog USP33 within this variable domain. The activation mechanisms of DUBs are not fully understood. However, it has been proposed that DUB activity is initiated by substrate binding (33). To identify putative interaction domains in USP20 involved in binding the β2AR, we generated USP20 deletion mutants spanning each of the protein's domains and tested them in coimmunoprecipitation assays. As shown in Fig. 8, A and B, β2AR is able to associate with each of these USP20 subdomain mutants, including the central phosphorylation domain (amino acids 269–390), although to a lesser degree than the full-length protein. To verify whether USP20 phosphorylation within the variable domain affects its interaction with the β2AR, we generated the deletion construct USP20 269–390 with S333A and S333D mutations and examined coprecipitation with the β2AR. As shown in Fig. 8, C and D, S333A and wild-type constructs displayed association with the β2AR, but S333D showed a significantly decreased interaction. These binding data strongly suggest that seryl 333-phosphorylated USP20 has lesser affinity for the substrate β2AR than the dephosphorylated form and that this decrease in substrate affinity might be an added cause for the lack of DUB activity of USP20 S333D toward the β2AR.

FIGURE 8.

Phosphorylation of serine 333 in the insertion domain of USP20 regulates association with the β2AR. A, schematic showing the wild-type and truncated forms of USP20. B, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were transiently transfected with full-length or truncated forms of HA-USP20. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were starved for 60 min and left unstimulated or stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol for 15 min. The receptors were isolated with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel and immunoblotted with antibodies specific to HA (for USP20) and FLAG (M2, for β2AR). Top panel, the amounts of truncated forms and wild-type USP20 bound to the β2AR. Center panel, the amounts of receptor as detected by a FLAG antibody (M2). Bottom panel, the expression levels of truncated forms and wild-type USP20 in the lysates as detected by a HA antibody. IP, immunoprecipitation. C, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were transfected with HA-pcDNA3.0, HA-USP20269–390, HA-USP20269–390-S333A, or HA-USP20269–390-S333D and stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol for 15 min. The receptors were isolated with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel and immunoblotted with antibodies specific to HA and FLAG (M2). Top panel, the amounts of USP20269–390 bound to the β2AR. Center panel, the amounts of receptor as detected by a FLAG antibody (M2). Bottom panel, the expression levels of USP20269–390-WT and mutants in the lysates as detected by a HA antibody. D, quantification of USP20269–390 in receptor IPs from three independent experiments where maximal binding is 100%. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; between HA-pcDNA3.0 and others under isoproterenol-stimulated conditions; one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. NS, not stimulated.

Agonist-activated β2ARs Traffic to Autophagosomes

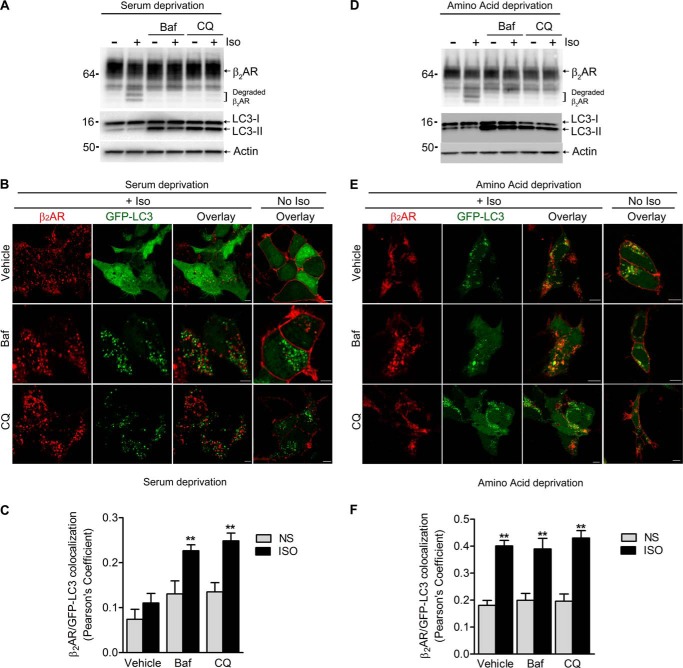

In HEK293 cells, degradation of exogenously expressed FLAG-β2ARs is detected as bands of smaller molecular sizes after isoproterenol stimulation for 4–6 h (21, 31). This isoproterenol-induced β2AR degradation is blocked by inhibitors of lysosomal proteases (leupeptin) as well as by chloroquine and bafilomycin A1, which prevent the fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 9A). This suggests that agonist-activated β2ARs traffic via autophagosomes before being degraded in lysosomal compartments of mammalian cells and that this localization in autophagosomes might regulate the timing of receptor degradation in lysosomes. Autophagy is a cellular degradation process in which cytoplasmic components are sequestered into newly formed membrane compartments (autophagosomes) and delivered into lysosomes for degradation (34, 35). Autophagy requires the modification of two proteins, ATG12 and ATG8 (LC3), via enzymatic pathways that are similar to ubiquitin conjugation (36). Modification of ATG12 is required at the initiation steps of the autophagosome, whereas LC3 lipidation (conversion of LC3I to LC3-II by conjugation with phosphatidylethanolamine) marks mature autophagosomes prior to fusion with lysosomes. LC3-II, but not LC3I, is localized to vesicles and serves as a marker for autophagosomes and its stabilization, and detection is facilitated by blocking lysosomal proteases (leupeptin) or by preventing autophagosome-lysosome fusion (chloroquine or bafilomycin A1 incubation (37)).

FIGURE 9.

Agonist-activated β2ARs traffic to autophagosomes. A, HEK293 cells stably transfected with FLAG-β2AR were serum-starved for 60 min. After starvation, the cells were pretreated with 400 nm bafilomycin A1 (Baf) or 25 μm chloroquine (CQ) for 10 min and additionally stimulated without or with 1 μm isoproterenol for 4 h, then lysed and analyzed using antibodies against β2AR, LC3-A, and β-actin. B, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were transiently transfected with pEGFP-LC3. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were serum-starved for 60 min and then pretreated with 400 nm Baf or 25 μm CQ, followed by stimulation with 1 μm isoproterenol for 4 h. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-β2AR and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit antibodies. Confocal images are shown with FLAG-β2AR in red and GFP-LC3 in green. Scale bar = 10 μm. C, histogram showing Pearson's correlation coefficients for the colocalization of β2AR (red) and GFP-LC3 (green). Data are mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.01 versus respective nonstimulated (NS) samples and vehicle + Iso, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni comparison. D–F, the experiments in A–C were repeated with only one modification. Instead of serum deprivation, we incubated the cells in Hanks' balanced salt solution to achieve amino acid starvation, which induces autophagy (60).

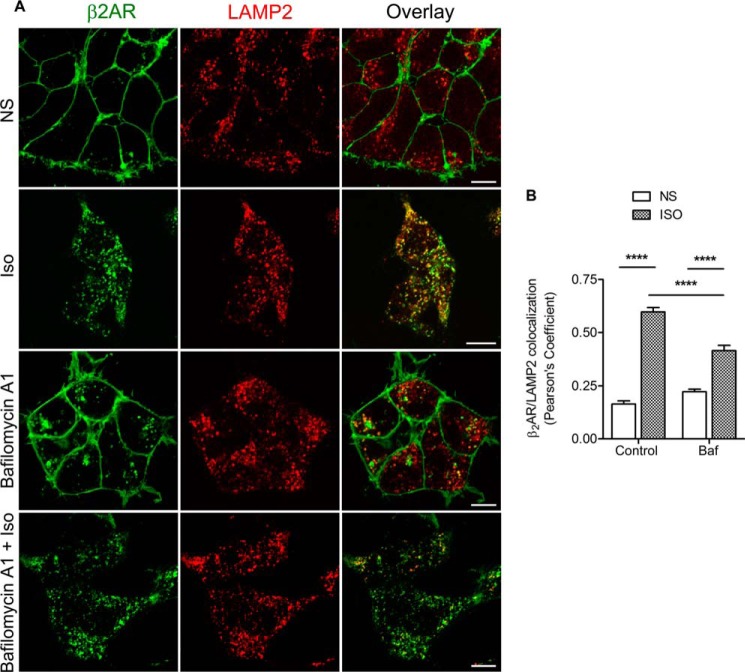

To define whether β2ARs traffic via autophagosomes, we next ascertained whether internalized β2ARs colocalize with LC3-II. After 4 h of isoproterenol stimulation, β2ARs internalize into late endosomes and lysosomes, whereas coexpressed GFP-LC3 is mostly diffusely distributed with few puncta (i.e. GFP-LC3-II) in each cell (Fig. 9B, top row). The serum-starving condition that was used in the degradation assays can mildly induce autophagy, which is indicated by the presence of LC3-II (Fig. 9A, lanes 1 and 2) and a small increase in colocalization of β2AR and LC3-II (Fig. 9, B and C). When cells were treated with both isoproterenol and bafilomycin A1, we not only detected a dramatic redistribution of LC3-II to autophagosomes but also a robust colocalization of LC3-II and internalized β2AR (Fig. 9, B and C). A similar pattern of colocalization of β2AR and GFP-LC3-II was observed when cells were exposed to both isoproterenol and chloroquine, which blocks both β2AR and LC3-II degradation in the lysosomes (Fig. 9, B and C). When we used amino acid deprivation, which is a more potent inducer of autophagy than serum deprivation (23), isoproterenol induced similar β2AR degradation (Fig. 9D), but increased the induction of LC3-II and promoted its robust colocalization with internalized β2ARs (Fig. 9, D–F). Under these conditions, addition of chloroquine or bafilomycin A1 did not further increase β2AR-LC3-II colocalization, although more LC3-II protein was detectable in immunoblots (Fig. 9, D–F). Interestingly, bafilomycin A1, which enhanced β2AR-LC3-II association under serum deprivation (Fig. 9, B and C), reciprocally decreased the colocalization of internalized β2ARs with LAMP2, a marker protein for late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 10, A and B).

FIGURE 10.

Bafilomycin A1 diminishes colocalization of β2ARs and LAMP2. A, HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were serum-starved for 60 min and then pretreated with 400 nm bafilomycin A1 (Baf) followed by stimulation with 1 μm isoproterenol for 4 h. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-β2AR and anti-LAMP2 followed by secondary IgGs as in Fig. 6. Confocal images are shown with FLAG-β2AR in green and LAMP2 in red. Scale bar = 10 μm. NS, nonstimulated. B, Pearson's correlation coefficients calculated for β2AR and LAMP2 colocalization (mean ± S.E.) in the respective cells for isoproterenol-stimulated and non-stimulated conditions. ****, p < 0.0001 between indicated samples.

Although bafilomycin A1 is widely used as an inhibitor of autophagy, it is actually a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) in cells and inhibits the acidification and fusion of organelles containing this enzyme, such as lysosomes and endosomes (38). Therefore, both chloroquine and bafilomycin A1 potentially stall intracellular trafficking by inhibiting fusion of late endosomes or multivesicular bodies (which form the trafficking route for the β2AR via traditional endocytosis) with lysosomes or block the fusion of autophagosomes with any of these vesicles. If β2AR trafficking progressed only through the traditional endocytic route, we would not have observed a robust colocalization of internalized β2ARs with LC3-II, especially with bafilomycin A1, because most of the receptors would be localized in late endosomes (7), and most of the LC3-II would be associated with autophagosomes (23). Because our assays reveal a robust colocalization of β2ARs and LC3-II, it is likely that β2ARs divert from traditional endocytosis and traffic through autophagosomes when cellular autophagy is induced.

USP20 Seryl 333 Phosphorylation and β2AR Ubiquitination Promote Receptor Trafficking through Autophagosomes

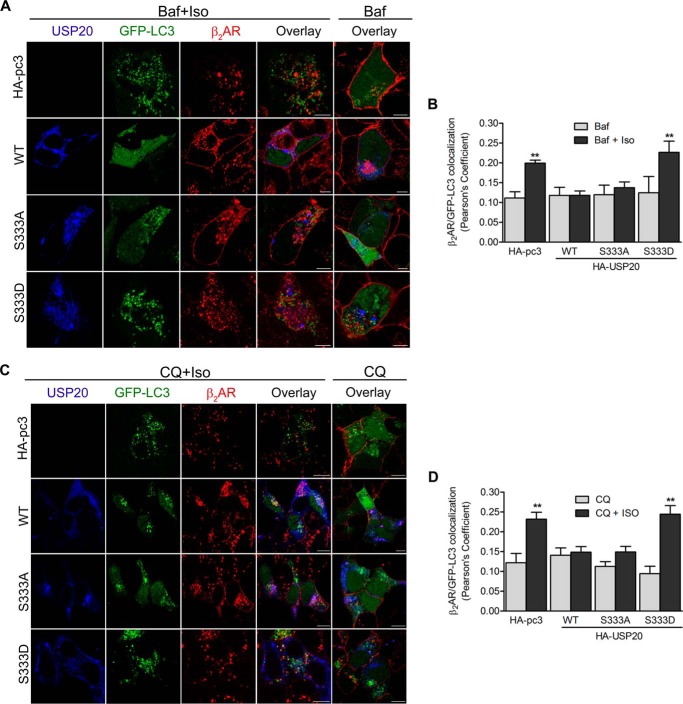

We next tested whether USP20 overexpression and its DUB activity would affect β2AR-LC3-II colocalization in autophagic vesicles. We cotransfected GFP-LC3, vector, or USP20 (either wild-type, S333A, or S333D) and determined the localization of each protein in unstimulated and agonist-stimulated cells by confocal microscopy. In the absence of isoproterenol stimulation, we detect only a small amount of colocalization of the β2AR and GFP-LC3-II with bafilomycin A1 (Fig. 11A, Baf, fifth column) or chloroquine (Fig. 11C, CQ, fifth column). However, isoproterenol stimulation along with chloroquine or bafilomycin A1 induced robust colocalization of the internalized β2AR and GFP-LC3-II in cells transfected with vector (endogenous USP20) or with S333D (where the DUB activity is inhibited). On the other hand, overexpression of USP20 wild-type or S333A significantly decreased colocalization of GFP-LC3-II and internalized β2ARs (Figs. 11, A–D). These data suggest that USP20 activity blocks or reverses β2AR trafficking at the autophagosomes en route to the lysosomes.

FIGURE 11.

Serine 333 phosphorylation of USP20 promotes β2AR trafficking to autophagosomes. HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-β2AR were transiently cotransfected with pEGFP-LC3 and HA-pcDNA3.0, HA-USP20-WT, HA-USP20-S333A, or HA-USP20-S333D. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were serum-starved for 60 min and then pretreated with 400 nm bafilomycin A1 (Baf, A) or 25 μm chloroquine (CQ, C), followed by stimulation with 1 μm isoproterenol for 4 h. Cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-β2AR and anti-USP20. Confocal images are shown with the GFP-LC3 in green, FLAG-β2AR in red (Alexa Fluor 594), and USP20 in blue (Alexa Fluor 633). Scale bar = 10 μm. The histograms (B, bafilomycin A1; D, chloroquine) show quantification of colocalization in merged images for the two channels, β2AR (red) and GFP-LC3 (green), in each sample (Pearson's coefficient). Significant differences between HA-pcDNA3.0 and HA-USP20-WT, HA-USP20-S333A, or HA-USP20-S333D under isoproterenol-stimulated conditions were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. **, p < 0.01, Iso-stimulated versus respective unstimulated samples; **, p < 0.01 versus WT or S333A.

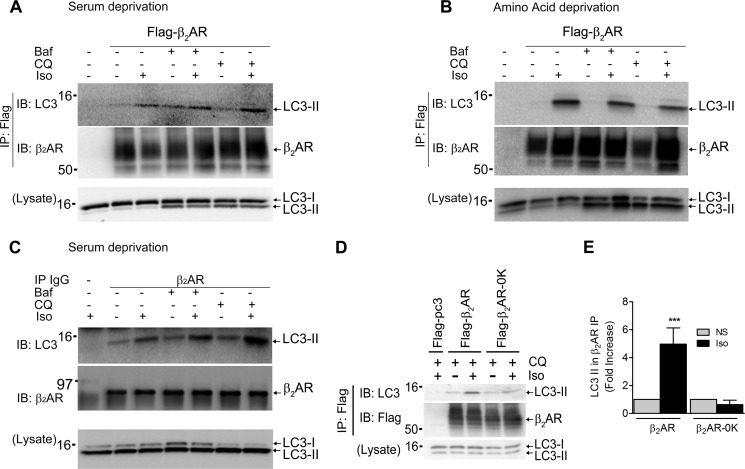

We also determined whether β2AR and LC3-II show protein-protein interaction in addition to localizing in the same subcellular compartment. We used either serum deprivation or amino acid deprivation and immunoprecipitated FLAG-β2ARs from cells treated with vehicle or Iso and assessed binding of endogenous LC3I and LC3-II. LC3I displayed minimal binding with the β2AR. However, LC3-II displayed an agonist-dependent interaction that was increased dramatically in cells starved of amino acids (Fig. 12, A and B). Addition of either bafilomycin A1 or chloroquine enhanced the association of LC3-II and β2ARs under serum deprivation but not under amino acid deprivation (Fig 12, A and B). This is probably because, under amino acid deprivation, the association of β2AR and LC3-II reached a maximum level even in the absence of these inhibitors, as also seen in the colocalization assays (Fig. 9, E and F). Additionally, to evaluate whether endogenously expressed β2ARs can bind LC3-II, we performed the same coimmunoprecipitation using primary vascular smooth muscle cells by employing methods we have reported previously (22). We detected isoproterenol-induced LC3-II binding with the β2AR, which was enhanced by the addition of either bafilomycin A1 or chloroquine (Fig 12C).

FIGURE 12.

Agonist stimulation promotes β2AR and LC3-II interaction, which is regulated by ubiquitination of the β2AR. A, HEK293 cells with or without stable transfection of FLAG-β2AR were serum-starved for 1 h and then treated with either 400 nm bafilomycin A1 (Baf) or 25 μm chloroquine (CQ) with or without isoproterenol for 4 h. The receptors were isolated with M2 anti-FLAG affinity gel. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were separated by SDS-PAGE and serially immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies specific to LC3A and β2AR. Lysates were immunoblotted with LC3A antibody. B, the experiment was performed as in A, except that the cells were starved with Hanks' balanced salt solution. C, early passage rat vascular smooth muscle cells were serum-starved for 14 h and then stimulated with or without isoproterenol along with vehicle, chloroquine, or bafilomycin A1 for 4 h. Endogenous β2ARs were immunoprecipitated with a β2AR IgG (M-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and the IPs were serially probed for LC3 with a mouse monoclonal LC3-β IgG (G-2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and β2AR. D, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type β2AR (FLAG-β2AR) and a mutant receptor with no lysine residues (FLAG-β2AR-0K). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were starved for 1 h and then pretreated with 25 μm chloroquine for 10 min, followed by stimulation with 1 μm isoproterenol for 4 h, and the coimmunoprecipitation of β2AR and LC3 was evaluated as in A. E, -fold increase of LC3-II in β2AR immunoprecipitates obtained after isoproterenol stimulation (mean ± S.E. of five independent experiments). ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni comparison.

Because the effects of S333A and S333D on β2AR-LC3II colocalization (Fig 11) paralleled their effects on β2AR ubiquitination (Fig. 6, A and B), we tested whether receptor ubiquitination could serve as a signal for its trafficking to autophagosomes. To address this, we compared wild-type β2AR and a β2AR mutant that is defective in ubiquitination (β2AR-0K) for LC3-II interaction. Previous studies have shown that this mutant receptor is not ubiquitinated by agonist stimulation (16, 22, 31, 39) and does not colocalize with LAMP2 in lysosomes (31). β2AR-0K is also impaired in LC3-II interaction (Fig. 12, D and E), suggesting that β2AR ubiquitination facilitates receptor trafficking to autophagosomes, and the robust LC3II-β2AR colocalization observed with coexpression of S333D is attributed to decreased DUB activity and stabilization of β2AR ubiquitination. In this scenario, ubiquitin moieties on the β2AR could function as “recognition tags” for LC3-II interaction and selective targeting of cargo to autophagosomes (40).

DISCUSSION

βARs signal through heterotrimeric G proteins and PKA as well as through β-arrestins via distinct mechanisms and ligand-induced conformations (41–44). β-Arrestins have multifaceted roles and act as adaptors for enzymes that degrade second messengers (desensitization), function as scaffolds for protein kinases (signal transduction), and serve as adaptors for endocytic and ubiquitin pathway components (intracellular trafficking) (45, 46). We discovered an unexpected convergence of the second messenger activated PKA and the β-arrestin-dependent trafficking pathways. Our data suggest that both facilitate the lysosomal trafficking of agonist-activated β2AR and that they do so by acting at distinct steps of posttranslational regulation of the βAR. As reported previously, β-arrestin promotes ubiquitination of the agonist-bound receptor by escorting the E3 ligase Nedd4 (19, 20), and, as shown in this work, PKA stabilizes ubiquitination of the β2AR by phosphorylating and deactivating the cognate deubiquitinase USP20. This mode of deactivation of USP20 could be applicable to other GPCR-associated kinases because serine 333 containing a phosphorylation domain is a predicted site of phosphorylation for the AGC kinase sub family of protein kinases, which includes PKA, PKC, and PKG. Serine 333 phosphorylation of USP20 could, therefore, be a general regulatory mechanism in GPCR trafficking, although, so far, only an interaction between USP20 and β2AR has been documented.

Upon agonist activation, most GPCRs internalize into vesicles called endosomes and may do so by different mechanisms at the plasma membrane (clathrin-coated vesicles, caveolae, uncoated vesicles, etc.) (47). However, upon localizing to endosomes, studies so far predict a direct route for degradation to lysosomes via late endosomes. This work reveals an unexpected navigation of activated receptors via autophagosomes. Autophagy is a distinct pathway of cellular degradation in which specific signals initiate formation of a phagophore that surrounds a variety of cytoplasmic components, including organelles, to form autophagosomes that then fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes (36). The colocalization and association of internalized, ubiquitinated β2AR with the autophagosome-specific marker LC3-II suggests that internalized receptors move through autophagosomes prior to lysosomal degradation.

Recent studies have implicated regulation of autophagy by taste receptors and regulation of neuronal cannabinoid receptors by beclin2, a component of the autophagy pathway, in an autophagy-independent manner (48–50). Our findings illustrate that, in addition to these mechanisms, both autophagy and endocytic trafficking orchestrate the destruction of internalized β2ARs in a ubiquitin-dependent manner. Because recent studies suggest that selective autophagy, a pathway choreographed by specific protein interactions, is guided by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding domains (51), it is likely that USP20 may have unappreciated roles in deubiquitinating components or interactors of autophagy-associated proteins in addition to its effects of deubiquitinating receptor cargo.

Site-specific phosphorylation of USP20 by PKA within the unique insertion domain is a novel mechanism of “turning off” this deubiquitinating enzyme. In general, DUBs are expressed as fully processed enzymes, and ongoing research is targeted toward understanding how these enzymes, which are synthesized and expressed in their active form, refrain from nonspecific and random deubiquitination of cellular proteins (33). DUBs and their activity have been designated as cryptic in nature, and their activation has been proposed to be triggered upon substrate binding and posttranslational modifications or by protein-protein interaction (52–55). About 85 DUBs are expressed in human cells, and the USP subfamily with about 55 members represents the largest among the five families of DUBs. Each USP may affect a subset of proteins expressed in cells (56) and, so far, a handful of proteins, including the βARs have been identified as physiological substrates of USP20. Nonetheless, it is very likely that, with respect to each of these substrates, USP20 could have specific binding, activation, and deactivation patterns or switches. For the deubiquitination of the β2AR, USP20 phosphorylation by PKA and dephosphorylation by a cellular phosphatase could serve as reversible off/on switches. It remains to be determined whether this phosphatase is scaffolded by β-arrestins, as has been shown for regulating dopamine signaling via the D2 dopamine receptor (57). An imbalance between USP20 phosphorylation/dephosphorylation can perhaps serve as a causative factor toward disease progression, as may be occurring in βAR desensitization in heart failure, where USP20 serine phosphorylation may be irreversible.

That βAR expression is diminished in failing hearts has been known for decades, but the factors or specific trafficking signals that affect βAR degradation in heart failure remain unknown. Our studies suggest that stimulation of cellular autophagy may also provoke β2AR trafficking through autophagosomes. Autophagic activity is augmented in failing hearts (58), but whether this pathway is beneficial or detrimental for cardiomyocyte survival remains controversial (59). Deciphering the relationship between induction of autophagy, trafficking of βARs, and activity of USP20 in healthy versus diseased hearts constitutes an important direction for future research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robert J. Lefkowitz for advice and insights and Dr. Paul Insel for S49 lymphoma cell lines and suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL080525 (to S. K. S.).

- βAR

- β-adrenergic receptor

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- DUB

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-like modifier

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- Iso

- isoproterenol

- VS

- vinyl sulfone

- DPBS

- Dulbecco's PBS.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lohse M. J., Benovic J. L., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1990) Multiple pathways of rapid β 2-adrenergic receptor desensitization. Delineation with specific inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 3202–3211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reiter E., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) GRKs and β-arrestins: roles in receptor silencing, trafficking and signaling. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 17, 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) The role of β-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J. Cell Sci. 115, 455–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2005) Transduction of receptor signals by β-arrestins. Science 308, 512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sibley D. R., Lefkowitz R. J. (1985) Molecular mechanisms of receptor desensitization using the β-adrenergic receptor-coupled adenylate cyclase system as a model. Nature 317, 124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouvier M., Collins S., O'Dowd B. F., Campbell P. T., de Blasi A., Kobilka B. K., MacGregor C., Irons G. P., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1989) Two distinct pathways for cAMP-mediated down-regulation of the β 2-adrenergic receptor: phosphorylation of the receptor and regulation of its mRNA level. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 16786–16792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moore C. A., Milano S. K., Benovic J. L. (2007) Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 451–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Premont R. T., Gainetdinov R. R. (2007) Physiological roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 511–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vasudevan N. T., Mohan M. L., Goswami S. K., Naga Prasad S. V. (2011) Regulation of β-adrenergic receptor function: an emphasis on receptor resensitization. Cell Cycle 10, 3684–3691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shenoy S. K. (2007) Seven-transmembrane receptors and ubiquitination. Circ. Res. 100, 1142–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrara N., Komici K., Corbi G., Pagano G., Furgi G., Rengo C., Femminella G. D., Leosco D., Bonaduce D. (2014) β-Adrenergic receptor responsiveness in aging heart and clinical implications. Front. Physiol. 4, 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rockman H. A., Koch W. J., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature 415, 206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hislop J. N., von Zastrow M. (2011) Role of ubiquitination in endocytic trafficking of G-protein-coupled receptors. Traffic 12, 137–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mukhopadhyay D., Riezman H. (2007) Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science 315, 201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marchese A., Trejo J. (2013) Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of G protein-coupled receptor trafficking and signaling. Cell. Signal. 25, 707–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shenoy S. K., McDonald P. H., Kohout T. A., Lefkowitz R. J. (2001) Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated β 2-adrenergic receptor and β-arrestin. Science 294, 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marchese A., Benovic J. L. (2001) Agonist-promoted ubiquitination of the G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 mediates lysosomal sorting. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45509–45512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwarz L. A., Patrick G. N. (2012) Ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis, trafficking and turnover of neuronal membrane proteins. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 49, 387–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shenoy S. K., Xiao K., Venkataramanan V., Snyder P. M., Freedman N. J., Weissman A. M. (2008) Nedd4 mediates agonist-dependent ubiquitination, lysosomal targeting, and degradation of the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22166–22176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han S. O., Kommaddi R. P., Shenoy S. K. (2013) Distinct roles for β-arrestin2 and arrestin-domain-containing proteins in β2 adrenergic receptor trafficking. EMBO Rep. 14, 164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berthouze M., Venkataramanan V., Li Y., Shenoy S. K. (2009) The deubiquitinases USP33 and USP20 coordinate β2 adrenergic receptor recycling and resensitization. EMBO J. 28, 1684–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Han S. O., Xiao K., Kim J., Wu J. H., Wisler J. W., Nakamura N., Freedman N. J., Shenoy S. K. (2012) MARCH2 promotes endocytosis and lysosomal sorting of carvedilol-bound β2-adrenergic receptors. J. Cell Biol. 199, 817–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. (2010) Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140, 313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee I. H., Cao L., Mostoslavsky R., Lombard D. B., Liu J., Bruns N. E., Tsokos M., Alt F. W., Finkel T. (2008) A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3374–3379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rape M., Jentsch S. (2002) Taking a bite: proteasomal protein processing. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, E113–E116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Borodovsky A., Kessler B. M., Casagrande R., Overkleeft H. S., Wilkinson K. D., Ploegh H. L. (2001) A novel active site-directed probe specific for deubiquitylating enzymes reveals proteasome association of USP14. EMBO J. 20, 5187–5196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hemelaar J., Borodovsky A., Kessler B. M., Reverter D., Cook J., Kolli N., Gan-Erdene T., Wilkinson K. D., Gill G., Lima C. D., Ploegh H. L., Ovaa H. (2004) Specific and covalent targeting of conjugating and deconjugating enzymes of ubiquitin-like proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 84–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oakley R. H., Laporte S. A., Holt J. A., Barak L. S., Caron M. G. (1999) Association of β-arrestin with G protein-coupled receptors during clathrin-mediated endocytosis dictates the profile of receptor resensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32248–32257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guo Y., Wilderman A., Zhang L., Taylor S. S., Insel P. A. (2012) Quantitative proteomics analysis of the cAMP/protein kinase A signaling pathway. Biochemistry 51, 9323–9332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zambon A. C., Zhang L., Minovitsky S., Kanter J. R., Prabhakar S., Salomonis N., Vranizan K., Dubchak I., Conklin B. R., Insel P. A. (2005) Gene expression patterns define key transcriptional events in cell-cycle regulation by cAMP and protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8561–8566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xiao K., Shenoy S. K. (2011) β2-Adrenergic receptor lysosomal trafficking is regulated by ubiquitination of lysyl residues in two distinct receptor domains. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12785–12795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ye Y., Scheel H., Hofmann K., Komander D. (2009) Dissection of USP catalytic domains reveals five common insertion points. Mol. Biosyst. 5, 1797–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reyes-Turcu F. E., Ventii K. H., Wilkinson K. D. (2009) Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 363–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Appelqvist H., Wäster P., Kågedal K., Öllinger K. (2013) The lysosome: from waste bag to potential therapeutic target. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 214–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saftig P., Klumperman J. (2009) Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: trafficking meets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ohsumi Y. (2001) Molecular dissection of autophagy: two ubiquitin-like systems. Nat. Rev. 2, 211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rubinsztein D. C., Cuervo A. M., Ravikumar B., Sarkar S., Korolchuk V., Kaushik S., Klionsky D. J. (2009) In search of an “autophagomometer.” Autophagy 5, 585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Klionsky D. J., Elazar Z., Seglen P. O., Rubinsztein D. C. (2008) Does bafilomycin A1 block the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes? Autophagy 4, 849–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang W., Hoang Q., Clark R. B., Fishman P. H. (2008) Accelerated dephosphorylation of the β2-adrenergic receptor by mutation of the C-terminal lysines: effects on ubiquitination, intracellular trafficking, and degradation. Biochemistry 47, 11750–11762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kraft C., Peter M., Hofmann K. (2010) Selective autophagy: ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 836–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shenoy S. K., Drake M. T., Nelson C. D., Houtz D. A., Xiao K., Madabushi S., Reiter E., Premont R. T., Lichtarge O., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) β-Arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the β2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1261–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim I. M., Tilley D. G., Chen J., Salazar N. C., Whalen E. J., Violin J. D., Rockman H. A. (2008) β-Blockers alprenolol and carvedilol stimulate β-arrestin-mediated EGFR transactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14555–14560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kahsai A. W., Xiao K., Rajagopal S., Ahn S., Shukla A. K., Sun J., Oas T. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (2011) Multiple ligand-specific conformations of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 692–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shukla A. K., Manglik A., Kruse A. C., Xiao K., Reis R. I., Tseng W. C., Staus D. P., Hilger D., Uysal S., Huang L. Y., Paduch M., Tripathi-Shukla P., Koide A., Koide S., Weis W. I., Kossiakoff A. A., Kobilka B. K., Lefkowitz R. J. (2013) Structure of active β-arrestin-1 bound to a G-protein-coupled receptor phosphopeptide. Nature 497, 137–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shenoy S. K., Lefkowitz R. J. (2011) β-Arrestin-mediated receptor trafficking and signal transduction. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 32, 521–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. DeWire S. M., Ahn S., Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2007) β-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 483–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tian X., Kang D. S., Benovic J. L. (2014) β-arrestins and G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 219, 173–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. He C., Wei Y., Sun K., Li B., Dong X., Zou Z., Liu Y., Kinch L. N., Khan S., Sinha S., Xavier R. J., Grishin N. V., Xiao G., Eskelinen E. L., Scherer P. E., Whistler J. L., Levine B. (2013) Beclin 2 functions in autophagy, degradation of G protein-coupled receptors, and metabolism. Cell 154, 1085–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hiebel C., Kromm T., Stark M., Behl C. (2014) Cannabinoid receptor 1 modulates the autophagic flux independent of mTOR- and BECLIN1-complex. J. Neurochem. 131, 484–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wauson E. M., Zaganjor E., Lee A. Y., Guerra M. L., Ghosh A. B., Bookout A. L., Chambers C. P., Jivan A., McGlynn K., Hutchison M. R., Deberardinis R. J., Cobb M. H. (2012) The G protein-coupled taste receptor T1R1/T1R3 regulates mTORC1 and autophagy. Mol. Cell 47, 851–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stolz A., Ernst A., Dikic I. (2014) Cargo recognition and trafficking in selective autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Köhler A., Zimmerman E., Schneider M., Hurt E., Zheng N. (2010) Structural basis for assembly and activation of the heterotetrameric SAGA histone H2B deubiquitinase module. Cell 141, 606–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Samara N. L., Datta A. B., Berndsen C. E., Zhang X., Yao T., Cohen R. E., Wolberger C. (2010) Structural insights into the assembly and function of the SAGA deubiquitinating module. Science 328, 1025–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cohn M. A., Kowal P., Yang K., Haas W., Huang T. T., Gygi S. P., D'Andrea A. D. (2007) A UAF1-containing multisubunit protein complex regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol. Cell 28, 786–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kessler B. M., Edelmann M. J. (2011) PTMs in conversation: activity and function of deubiquitinating enzymes regulated via post-translational modifications. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 60, 21–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sowa M. E., Bennett E. J., Gygi S. P., Harper J. W. (2009) Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138, 389–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beaulieu J. M., Sotnikova T. D., Marion S., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2005) An Akt/β-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 122, 261–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xie M., Morales C. R., Lavandero S., Hill J. A. (2011) Tuning flux: autophagy as a target of heart disease therapy. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 26, 216–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gottlieb R. A., Mentzer R. M., Jr. (2013) Autophagy: an affair of the heart. Heart Fail. Rev. 18, 575–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fung C., Lock R., Gao S., Salas E., Debnath J. (2008) Induction of autophagy during extracellular matrix detachment promotes cell survival. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 797–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]