Abstract

Background

Outside of Africa, P. falciparum and P. vivax usually coexist. In such co-endemic regions, successful malaria control programs have a greater impact on reducing falciparum malaria, resulting in P. vivax becoming the predominant species of infection. Adding to the challenges of elimination, the dormant liver stage complicates efforts to monitor the impact of ongoing interventions against P. vivax. We investigated molecular approaches to inform the respective transmission dynamics of P. falciparum and P. vivax and how these could help to prioritize public health interventions.

Methodology/ Principal Findings

Genotype data generated at 8 and 9 microsatellite loci were analysed in 168 P. falciparum and 166 P. vivax isolates, respectively, from four co-endemic sites in Indonesia (Bangka, Kalimantan, Sumba and West Timor). Measures of diversity, linkage disequilibrium (LD) and population structure were used to gauge the transmission dynamics of each species in each setting. Marked differences were observed in the diversity and population structure of P. vivax versus P. falciparum. In Bangka, Kalimantan and Timor, P. falciparum diversity was low, and LD patterns were consistent with unstable, epidemic transmission, amenable to targeted intervention. In contrast, P. vivax diversity was higher and transmission appeared more stable. Population differentiation was lower in P. vivax versus P. falciparum, suggesting that the hypnozoite reservoir might play an important role in sustaining local transmission and facilitating the spread of P. vivax infections in different endemic settings. P. vivax polyclonality varied with local endemicity, demonstrating potential utility in informing on transmission intensity in this species.

Conclusions/ Significance

Molecular approaches can provide important information on malaria transmission that is not readily available from traditional epidemiological measures. Elucidation of the transmission dynamics circulating in a given setting will have a major role in prioritising malaria control strategies, particularly against the relatively neglected non-falciparum species.

Author Summary

The malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax is a growing public health burden across the globe. Largely overshadowed by the more fatal P. falciparum parasite, increasing reports of anti-malarial drug resistance and life-threatening disease complications demand concerted efforts to eliminate P. vivax. Outside of Africa, P. vivax usually co-exists with P. falciparum. In these regions, malaria interventions have demonstrated greater success against falciparum. The authors genotyped P. vivax and P. falciparum parasites from 4 co-endemic sites in Indonesia, and used the data to gauge how frequently and how focally parasites were transmitted, and how much they spread between sites. Their results indicated that whilst the P. falciparum populations displayed evidence of low and unstable transmission, the P. vivax populations were more diverse and exhibited more stable transmission patterns, requiring different intervention approaches. Relative to P. falciparum, the P. vivax parasites demonstrated evidence of greater spread between populations, possibly facilitated by the dormant liver stage which enables P. vivax to be carried asymptomatically in patients for long periods of time. These findings highlight the need to reconcile the intervention requirements for non-falciparum malaria species in co-endemic regions, and the general utility of parasite genotyping to facilitate surveillance.

Introduction

Plasmodium vivax is a major global health burden, with an estimated 2.85 billion people living at risk of infection [1]. Rising levels of multidrug resistance and severe disease [2–7], and the demonstrated transmission amongst Duffy blood group-negative individuals [8–12], demand concerted efforts to control and eliminate the parasite. However, relative to the other major human malaria pathogen, P. falciparum, interventions against P. vivax have been less effective [13]. Critical to the success of control and elimination programs is the acquisition of data on the intensity and dynamics of local malaria transmission. Measures of transmission intensity have been used to inform public health interventions for P. falciparum [14], however the dormant hypnozoite stage of P. vivax result in its dynamics being far more challenging to interpret. Outside of Africa, P. vivax usually co-exists with P. falciparum. In these co-endemic regions, potential differences in the respective transmission of the two species further complicate decision-making on the prioritization of intervention activities.

Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of genotyping parasite population samples to inform on P. vivax and P. falciparum diversity, population structure and underlying transmission patterns [15–35]. These molecular approaches complement the more traditional measures of transmission intensity. As well as providing an independent gauge of intensity, parasite genotyping can inform on other features of transmission such as outbreak dynamics, infection spread within and across borders, and reservoirs of infection [36]. However few studies have demonstrated the utility of genotyping to compare the transmission dynamics of co-endemic P. vivax and P. falciparum isolates [18,19,28]. A combination of the widely contrasting malaria epidemiology and the physical geography of the Indonesian archipelago rendered this an ideal setting within which to further address the comparative patterns of transmission in P. vivax and P. falciparum populations in multiple co-endemic sites.

Malaria remains a major public health burden in Indonesia, with over 400 thousand confirmed cases in 2012 representing just a fraction of the actual suspected burden [37]. Malaria caused by P. vivax infection is a particular concern in Indonesia owing to the occurrence of high-grade chloroquine-resistant infections [38,39]. In 2009, the Ministry of Health instigated a malaria control and elimination strategy to be rolled out island by island with the aim of achieving nation-wide malaria elimination by 2030. One of the greatest challenges in achieving this target is the extensive heterogeneity in malaria epidemiology across an archipelago comprising more than 6,000 inhabited islands. The country is characterised by marked variation in the incidence of malaria, distribution of Anopheles vectors, prevalence of anti-malarial drug resistance, and ethnic, cultural and socio-economic diversity [40]. Malaria caused by P. knowlesi is also an emerging problem in Indonesia. However, until recently, the burden of P. knowlesi malaria has not been comprehensively investigated in Indonesia, with only two published studies confirming the presence of this species [41,42]. Hence interventions need to be tailored to the epidemiological setting in question. Furthermore, the highly mobile population increases the risk of re-introduction of malaria to areas with no malaria transmission.

As a prerequisite to developing a comprehensive national surveillance for malaria transmission, we used simple genotyping methods to characterize the genetic diversity and structure of P. vivax and P. falciparum isolates collected between 2011 and 2013 at four Indonesian sites with differing endemicity. The resultant insights into the local P. vivax versus P. falciparum transmission dynamics are reviewed and interpreted in the context of the country’s malaria elimination goals. The broader implications for prioritization of intervention strategies in other regions of the globe where the prevalence of non-falciparum malaria is rising are also discussed.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites and Sample Collection

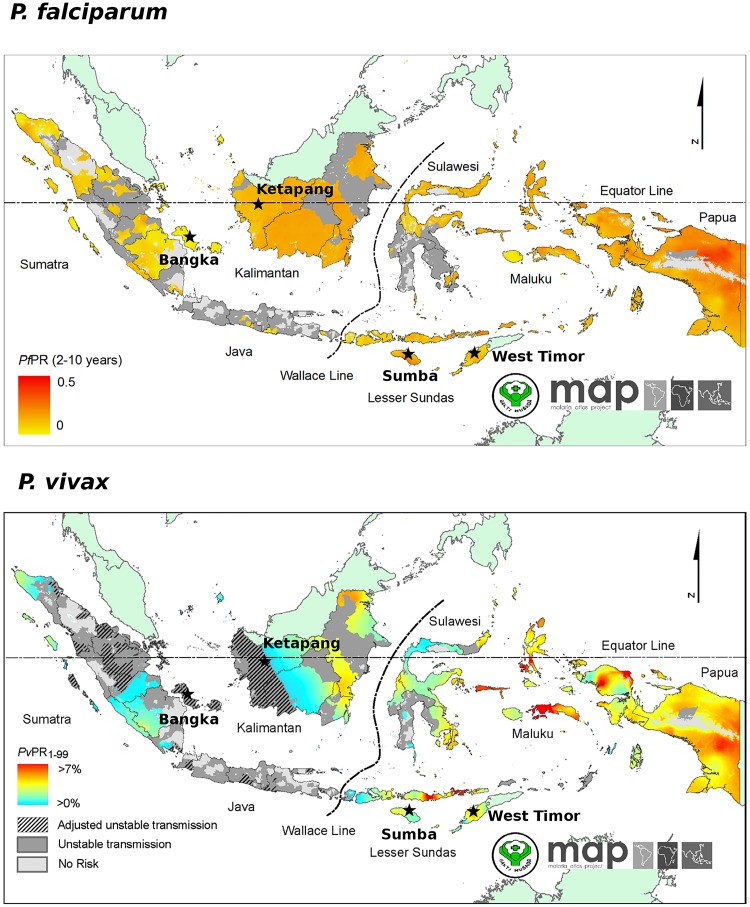

The study was conducted in two sites on Bangka island (Bangka-Belitung, Sumatra), one site in Ketapang Province in West Kalimantan, two sites in Sumba (East Nusa Tenggara) and one site in West Timor (East Nusa Tenggara) (Fig 1). Details on the study sites are provided in S1 Table. Bangka, Sumba and West Timor are defined as moderate stable endemic or ‘hypo-mesoendemic’, and the Kalimantan site as unstable endemic [14]. Whilst Bangka and Ketapang have been assigned goals of elimination by 2015, the goals for Sumba and West Timor are to reach pre-elimination by 2020, with national malaria elimination by 2030. In all four study sites, dihydroartemisinin—piperaquine is used as the primary treatment for both P. vivax and P. falciparum malaria as recommended by the Ministry of Health since 2008. As well as malaria incidence, the study sites exhibit several socio-economic and ecological differences reflective of the heterogeneity generally found across the Indonesian archipelago. Whilst Bangka is the largest producer of tin in Indonesia, in Ketapang the main industries are palm oil and rubber production and logging. In East Nusa Tenggara the main economy is subsistence agriculture, with Sumba being one of the poorest islands in Indonesia. The available information on vector species demonstrates heterogeneity across the study sites [43]. Details on the bionomics of each species can be found on the Malaria Atlas Project website [44]. Briefly, in West and Central Bangka, the dominant malaria vectors appear to be Anopheles leucosphyrus, An. latens and An. sundaicus sensu lato. All three species/species complexes can transmit both P. vivax and P. falciparum and tend to bite in the evening/night. Both endophilic and exophilic feeding behaviour has been demonstrated in An. sundaicus. s.l. and An. leucosphyrus. Whilst An. sundaicus. s.l. display varying degrees of indoor and outdoor resting, An. leucosphyrus and An. latens do not tend to rest indoors in the day. In Ketapang Province, An. balabacensis, An. leucosphyrus and An. latens are prevalent. An. barbirostris s.l. is also observed but likely to play little if any role in malaria transmission. An. balabacensis can transmit both P. vivax and P. falciparum, is largely exophagic, feeding in the evening/night. In East Nusa Tenaggarra, An. sundaicus s.l., An. balabacensis and An. flavirostis are prevalent. An. flavirostis is primarily zoophilic, displaying both endophagic and exophagic feeding in the evening/night. The vectorial capacity of this species in Indonesia remains unclear.

Fig 1. Prevalence maps.

These maps were generated by the Malaria Atlas Project, University of Oxford. The colour scales reflect the model-based geostatistical point estimates of the annual mean P. falciparum parasite rate in the 2–10 year age group (PfPR2–10) (top) [45] and P. vivax parasite rate in the 1–99 year age range (PvPR1–99) (bottom) [46] within the stable spatial limits of transmission in 2010. The approximate locations of the study sites described here are indicated with black stars.

In Kalimantan, Bangka and Sumba, parasite DNA was collected by both active and passive detection of malaria-infected individuals, whilst in West Timor only active case detection was undertaken (Table 1). Passive case detection involved symptomatic patients presenting to outpatient health clinics in West Bangka, a hospital in South West Sumba, and West Kalimantan. At these locations, local policy stipulates that all malaria treatment should be based on microscopic screening of thick blood films. Active case detection was performed either through community surveys or through screening of individuals with fever.

Table 1. Details of parasite sampling.

| Site | Species | Sampling | Collection period | No. patients | Median age, years | % male patients | Median parasite density, ul-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangka | P. falciparum | Active | Oct 2011 | 22 | 25 (5–72) | 59% (13/22) | 1,346 (103–31,010) |

| Passive | Oct 2011 | 36 | 30 (3–50) 1 | 89% (32/36) | 20,430 (198–755,400) 2 | ||

| All | Oct 2011 | 58 | 30 (3–72) 1 | 76% (45/58) | 5,671 (103–755,400) 2 | ||

| P. vivax | Active | Oct 2011 | 37 | 25 (1–45) | 65% (24/37) | 1,176 (69–87,770) 3 | |

| Passive | Oct 2011 | 49 | 27 (3–50) | 92% (45/49) | 5,923 (73–529,600) 1 | ||

| All | Oct 2011 | 86 | 25 (1–50) | 80% (69/86) | 3,083 (69–529,600) 4 | ||

| Ketapang | P. falciparum | Active | Oct 2012 | 3 | 7 (1–37) | 33% (1/3) | 392 (314–5187) |

| Passive | Nov 2012-Jul 2013 | 10 | 21 (17–57) | 90% (9/10) | 11,380 (391–36,240) | ||

| All | Oct 2012-Jul 2013 | 13 | 20 (1–57) | 77% (10/13) | 5,187 (314–36,240) | ||

| P. vivax | Active | Oct 2012 | 2 | 10 (8–12) | 50% (1/2) | 402 (115–688) | |

| Passive | Oct 2012-May 2013 | 11 | 18 (9–43) | 64% (7/11) | 3,746 (759–21,670) | ||

| All | Oct 2012-May 2013 | 13 | 17 (8–43) | 62% (8/13) | 2,589 (115–21,670) | ||

| Sumba | P. falciparum | Active | Jan-Nov 2012 | 45 | 9 (3–65) | 53% (34/45) | 4,052 (96–446,400) 2 |

| Passive | Jan-Feb 2012 | 15 | 15 (1–54) | 53% (8/15) | 38,370 (7,080–748,700) 5 | ||

| All | Jan-Nov 2012 | 60 | 10 (1–65) | 53% (32/60) | 7,080 (96–748,700) 7 | ||

| P. vivax | Active | Jan-Nov 2012 | 31 | 5 (0–30) | 55% (17/31) | 1,290 (69–20,050) 2 | |

| Passive | Jan-Sep 2012 | 9 | 30 (5–54) | 78% (7/9) | 9,923 (5,980–64,230) 2 | ||

| All | Jan-Nov 2012 | 40 | 5.5 (0–54) | 60% (24/40) | 4,091 (69–64,230) 4 | ||

| West Timor | P. falciparum | Active | Jun-Jul 2013 | 35 | 16 (2–67) | 60% (21/35) | 480 (32–20,200) |

| P. vivax | Active | Jun 2013 | 29 | 6 (1–37) | 45% (13/29) | 840 (48–11,000) | |

| All | P. falciparum | All | Oct 2011-Jul 2013 | 166 | 18 (1–72) 1 | 65% (108/166) | 3,099 (32–755,400) 9 |

| P. vivax | All | Oct 2011-Jun 2013 | 168 | 18 (0.5–54) | 68% (114/168) | 2,110 (48–529,600) 8 |

1–9 Superscript indicates the number of patients with missing data.

Following informed consent of the patient or their guardian, individuals with P. falciparum or P. vivax parasitaemia detected by blood film examination were asked to donate a venous (~1–2 ml) or capillary (~250 ul) blood sample collected into an EDTA-coated Vacutainer or microtainer or an anticoagulant-free 0.5 ml Eppendorf tube. Blood samples were stored at 2–8°C for up to 2 weeks, and -80°C for longer-term storage.

DNA Extraction and Species Confirmation

DNA extraction was undertaken using the QIAamp blood mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Plasmodium spp. was confirmed by PCR using the method described by Snounou et al. [47] and Boonma et al. [48].

Genotyping

P. falciparum genotyping was undertaken at nine previously described short tandem repeat (STR) markers including ARAII, PfPK2, poly-alpha, TA1, TA42, TA60,TA81, TA87 and TA109, using the primers and PCR conditions described by Anderson and colleagues [49].

P. vivax genotyping was undertaken at nine previously described STR markers including Pv3.27, msp1F3, MS1, MS5, MS8, MS10, MS12, MS16 and MS20 [50,51]. These markers are included in a consensus panel selected by partners within the Asia Pacific Malaria Elimination Network (www.apmen.org). The Pv3.27, MS16 and msp1F3 loci were amplified using methods described elsewhere [15]. The protocol for the remaining loci and the details of the primer sequences and chromosomal locations for each marker have been provided previously [15,20].

The labelled PCR products were sized by denaturing capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer with GeneScan LIZ-600 (Applied Biosystems) internal size standards. Genotype calling was facilitated with GeneMapper Version 4.0. To reduce potential artefacts, an arbitrary fluorescent intensity threshold of 50 rfu was applied for peak detection. All electropherogram traces were additionally inspected manually. For each isolate, at each locus, the predominant allele and any additional alleles with minimum 33% height of the predominant allele were scored [49].

Population Genetic Analysis

An infection was defined as polyclonal if more than one allele was observed at one or more loci. The Multiplicity of infection (MOI) for a given sample was defined as the maximum number of alleles observed at any of the loci investigated. With the exception of measures of polyclonality and MOI, only the predominant allele at each locus in each isolate was used for analysis [49]. The expected heterozygosity (H E) was measured as an index of population diversity using the formula H E = [n/ (n-1)] [1-Σp i 2], where n is the number of isolates analyzed and pi is the frequency of the ith allele in the population. The pairwise F ST metric was used to gauge the genetic distance between populations. Calculations were undertaken using Arlequin software (version 3.5) [52]. Standardized measures (F’ST) were additionally calculated to adjust for high marker diversity [53]. Population structure was further assessed using STRUCTURE software version 2.3.3 [54]. Twenty replicates, with 100,000 burn-in and 100,000 post burn-in iterations were run for each of K (populations) from 1–10 using the model parameters of admixture with correlated allele frequencies. The most probable K was derived by applying the delta K method [55]. STRUCTURE results were displayed using bar plots prepared with distruct software version 1.1 [56]. Multi-locus haplotypes were reconstructed from the predominant allele at each locus in isolates with no missing data. Multi-locus linkage disequilibrium (LD) was measured by the standardised index of association (I A S) using the web-based LIAN 3.5 software [57]. The significance of the I A S estimates was assessed using 10,000 random permutations of the data. For each population, LD was assessed in 1) all samples, 2) samples with a maximum of one multi-allelic locus, and 3) with each unique haplotype represented just once. The genetic relatedness between sample pairs was assessed by measuring the proportion of alleles shared between multi-locus haplotype pairs (ps). Using (1-ps) as a measure of genetic distance [58], an unrooted neighbour-joining tree [59] was generated with the ape package in R [60]. Mantel’s r-test was used to assess the correlation between genetic and temporal distance using the ade4 package in R [61].

Statistical Tests

Statistical comparisons of patient gender ratio and infection polyclonality between sites and species were undertaken using Pearson’s Chi-square test. The significance of difference between sites and species in patient age, parasite density and expected heterozygosity were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical comparison of the MOI between sites and species was undertaken using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. All tests were performed using R software, with a significance threshold of 0.05.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Eijkman Institute Research Ethics Commission (EIREC) number 45/2011. Written informed consent was obtained from all adults or a parent or guardian for participants less than 18 years of age.

Results

Patient Sampling

Between October 2011 and July 2013, a total of 334 blood samples were collected from malaria-infected individuals across the 4 sites (Table 1). With the exception of Kalimantan, where caution is advised in data interpretation, a minimum of 30 isolates were available for each species in each site. In Bangka and Sumba, malaria-positive individuals detected by both active (ACD) and passive case detection (PCD) contributed a moderate proportion of all samples. Comparison between these sample subsets did not however identify significant differences in sample diversity for either P. falciparum or P. vivax (S2 Table). Studies in other endemic regions have found similar results [62–66]. Therefore, ACD and PCD infections were pooled for subsequent analyses.

In Bangka and Kalimantan, the majority of patients were young adults. No significant difference was observed in the median age between P. vivax (25 years, range: 1–50) and P. falciparum patients (26 years, range: 1–72) (P = 0.223). In Bangka, the median age of PCD patients with P. vivax (27 years, range: 3–50) was 2 years older than the ACD patients (25 years, range: 1–45) (P = 0.021). In the same population, a 5 year difference was observed in the median age of the P. falciparum PCD (25 years, range: 5–72) versus ACD (30 years, range: 3–50) patients but the difference was not significant (P = 0.389). In Sumba and West Timor, the patient demographic was younger, with a significant difference in age between P. vivax (median 6 years, range: 0–54) and P. falciparum cases (median 13 years, range: 1–67) (P = 3.08 x 10–5). In Sumba, the median age of PCD patients with P. vivax (30 years, range: 5–54) was 25 years older than the ACD patients (5 years, range: 0–30) (P = 3.7 x 10–4), although caution is advised in interpretation owing to the modest sample size of the former group (n = 9). The median age of P. falciparum PCD patients (15 years, range: 1–54) was also higher than the ACD patients (9 years, range: 3–65) but the difference was not significant (P = 0.060).

Relative to the two western provinces (78% males), the representation of male patients was less skewed in Sumba and West Timor (55% males) (P = 1.78 x 10–5). In Bangka, the proportion of males was significantly higher amongst PCD versus ACD groups in both P. vivax (92% vs 65%, P = 0.005) and P. falciparum (89% vs 59%, P = 0.021). In Sumba, no significant difference was observed in gender proportions between PCD and ACD groups in either species (both P >0.05).

No significant difference was observed in the median parasite density (parasites ul-1 blood) between P. falciparum (3,099 ul-1, range: 32–755,400) and P. vivax (2,110 ul-1, range: 48–529,600) (P = 0.057). In both species, parasite density was significantly lower in ACD versus PCD patients. In P. vivax, the median parasite density was 1,126 ul-1 (range: 48–87,770) in ACD versus 6,551 ul-1 (range: 73–529,600) in PCD (P = 1.25 x 10–5). In P. falciparum, the median parasite density was 1,412 ul-1 (range: 32–446,439) in ACD versus 21,160 ul-1 (range: 198–755,400) in PCD (P = 7.28 x 10–11). In P. vivax, no significant difference was observed between the sites in the parasite density in the PCD (P = 0.097) or ACD (P = 0.261) patients. In P. falciparum, no significant difference was observed between the sites in the parasite density in the PCD (P = 0.084) patients. A significant difference was observed amongst the P. falciparum ACD patients (P = 8.01 x 10–5), largely reflecting the low parasite density in West Timor (median = 480 ul-1). The various differences observed in parasite density justified the implementation of the 33% predominant peak height threshold for calling additional alleles to reduce potential bias in characterising polyclonal infections.

Marker Properties

A summary of the genotype calls for each of the P. falciparum and P. vivax isolates in presented in the Supplementary material (S3 and S4 Tables, respectively). In P. falciparum, 12 (7.2%) and 3 (1.8%) isolates exhibited 1 and 3 genotyping failures, respectively. Whilst the TA109 and TA42 loci exhibited 9 (5.4%) and 8 (4.8%) genotyping failures, respectively, all other loci exhibited 3 or less (0–2%) failures. In P. vivax, 21 (12.5%) and 2 (1.2%) isolates exhibited 1 and 2 genotyping failures, respectively. With the exception of the MS5 locus, which exhibited 12 (7%) genotyping failures, all other markers exhibited 3 or less (0–1%) failures.

The distribution of allele frequencies at each marker is illustrated in S1 Fig, and measures of diversity in each population are presented in S5 Table. With the exception of the TA109 locus, where the predominant allele accounted for 96.2% of all alleles, all loci exhibited a minimum of one allele with minor allele frequency ≥5%. Owing to the low level of polymorphism, the TA109 locus was excluded from further analysis. After exclusion of the TA109 locus, the only observations of monomorphic loci within populations were at the TA42 and TA60 loci in Kalimantan, and the TA1 locus in West Timor (S5 Table). These loci were therefore excluded from the analysis of LD in the given populations.

Within-host and Population Diversity

A summary of polyclonality, MOI and population diversity is presented in Table 2. Variation was observed in the proportion of polyclonal P. falciparum infections (0–20%) and mean MOI (1–1.23) across sites, although none of the differences reached statistical significance. In contrast, the variation in the polyclonality of P. vivax infections (23–79%) was highly significant (P = 0.0002), as was the variation in mean MOI (1.23–1.90); P = 0.0002. Across the sites, higher proportions of polyclonal infections (P = 1.042 x 10–12) and higher mean MOI (P = 4.39 x 10–13) were observed in P. vivax versus P. falciparum. In P. falciparum, 41.7% (10/24) of polyclonal infections were multi-allelic at just one of the nine loci. A similar proportion of the polyclonal P. vivax infections, 38% (33/87) were multi-allelic at just one locus. In both P. falciparum and P. vivax 95% or more polyclonal infections could be identified with the seven most diverse markers.

Table 2. Within-host and population diversity.

| Island | Species | Polyclonal Infections, % | MOI, mean (range) | H E, mean ± SE (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangka | P. falciparum | 14% (8/58) | 1.14 (1–2) | 0.457 ± 0.072 (0.165–0.736) |

| P. vivax | 41% (35/86) | 1.47 (1–3) | 0.845 ± 0.037 (0.596–0.945) | |

| Kalimantan | P. falciparum | 0% (0/13) | 1.00 (1–1) | 0.397 ± 0.098 (0.000–0.731) |

| P. vivax | 23% (3/13) | 1.23 (1–2) | 0.851 ± 0.043 (0.621–0.982) | |

| Sumba | P. falciparum | 20% (12/60) | 1.23 (1–3) | 0.715 ± 0.069 (0.353–0.893) |

| P. vivax | 65% (26/40) | 1.75 (1–3) | 0.856 ± 0.036 (0.596–0.945) | |

| West Timor | P. falciparum | 11% (4/35) | 1.11 (1–2) | 0.522 ± 0.082 (0.000–0.686) |

| P. vivax | 79% (23/29) | 1.90 (1–3) | 0.806 ± 0.027 (0.670–0.916) |

P. falciparum population diversity varied between sites (H E = 0.397–0.715), with the highest diversity observed in Sumba. The differences between Sumba and each of Bangka (P = 0.031) and Kalimantan (P = 0.024) reached significance. Less variation was observed between the sites for P. vivax infections (H E = 0.806–0.856) (all P > 0.05). The diversity in P. vivax was consistently higher than in sympatric P. falciparum populations, reaching significance in Bangka, Kalimantan and West Timor (all P ≤ 0.001) but not Sumba (P > 0.05).

Population Structure and Differentiation

With the exception of Sumba and West Timor (F ST = 0.087; P <1 x10-5), the differentiation between the P. falciparum populations was high (F ST range: 0.238–0.415; all P <1 x10-5) (Table 3). Differentiation was lower in P. vivax (F ST range: -0.003–0.066), with significance in all comparisons (all P <1 x10-5) with the exception of Kalimantan, possibly reflecting the limited sample size.

Table 3. Pair-wise differentiation between sites.

| P. falciparum | Bangka | Kalimantan | Sumba | West Timor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangka | - | 0.420 | 0.637 | 0.686 |

| Kalimantan | 0.238 (P <1 x10-5) | - | 0.641 | 0.786 |

| Sumba | 0.264 (P <1 x10-5) | 0.255 (P <1 x10-5) | - | 0.234 |

| West Timor | 0.357 (P <1 x10-5) | 0.415 (P <1 x10-5) | 0.087 (P <1 x10-5) | - |

| P. vivax | Bangka | Kalimantan | Sumba | West Timor |

| Bangka | - | -0.019 | 0.263 | 0.381 |

| Kalimantan | -0.003 (P = 0.505) | - | 0.101 | 0.344 |

| Sumba | 0.039 (P <1 x10-5) | 0.014 (P = 0.243) | - | 0.362 |

| West Timor | 0.066 (P <1 x10-5) | 0.056 (P = 0.036) | 0.060 (P <1 x10-5) | - |

F ST (P-value) in lower left triangle. F’ ST in upper right triangle.

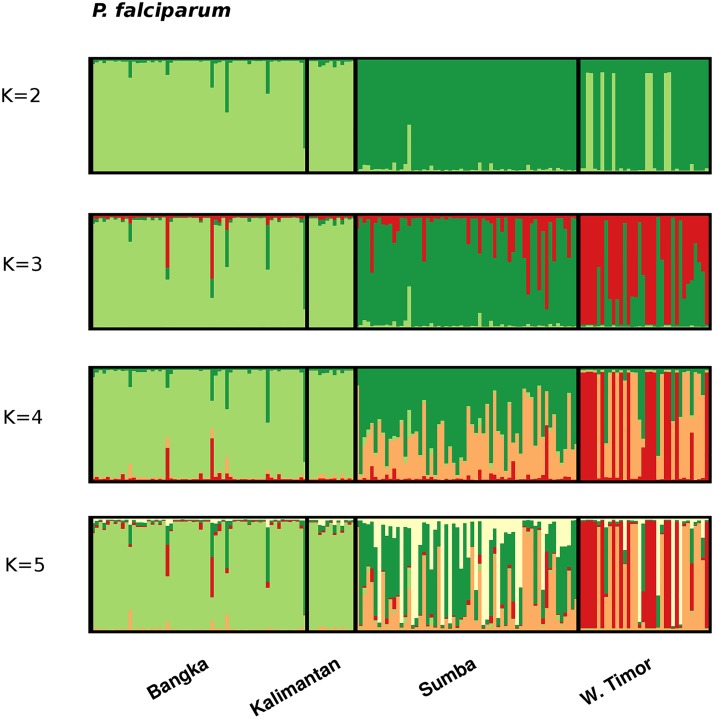

STRUCTURE analysis demonstrated clear sub-structure in the P. falciparum population (Fig 2). The delta K method demonstrated K = 2 as having the greatest likelihood (S2 Fig). At K = 2, the large majority of isolates from Bangka and Kalimantan, and approximately one third from West Timor demonstrated predominant ancestry to the K1 cluster, whilst all isolates from Sumba and the remaining two thirds from West Timor demonstrated predominant ancestry to the K2 cluster. At higher estimates of K, greater distinction was observed between the two eastern (Sumba and West Timor) populations, and increasing sub-structure was observed within West Timor.

Fig 2. Population structure in P falciparum.

Bar plots illustrating the population structure at K = 2–5 in P. falciparum. Each vertical bar represents an individual sample and each colour represents one of the K clusters (sub-populations) defined by STRUCTURE. For each sample, the predicted ancestry to each of the K sub-populations is represented by the colour-coded bars. K1 = light green, K2 = dark green, K3 = red, K4 = orange, and K5 = white.

In P. vivax, the delta K method identified K = 5 as the most likely number of sub-populations (S2 Fig). However, the large majority of isolates from all 4 populations demonstrated mixed ancestry to the various clusters (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Population structure in P. vivax.

Bar plots illustrating the population structure at K = 2–5 in P. vivax. K1 = light green, K2 = dark green, K3 = red, K4 = orange, and K5 = white.

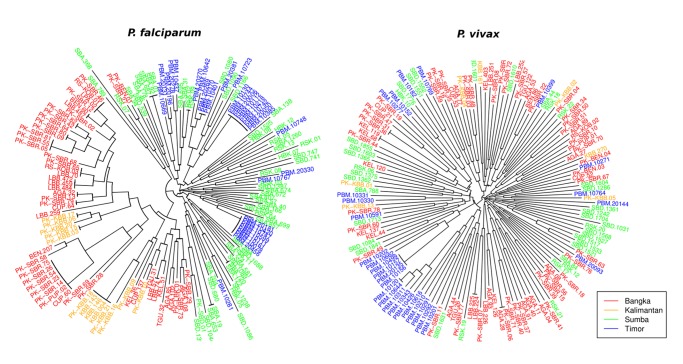

Relatedness

Neighbour-joining analysis demonstrated moderately distinct separation between the western and eastern P. falciparum isolates (Fig 4). Clusters of isolates with 4 or more identical or near-identical multi-locus haplotypes were observed in Bangka and West Timor, whilst the Sumba isolates were generally less related to one another.

Fig 4. Unrooted neighbour-joining tree illustrating the genetic relatedness between P. falciparum (top) and P. vivax (bottom) isolates.

Fewer identical isolates were observed in P. vivax relative to P. falciparum. The isolates from West Timor largely clustered together, and four identical isolates were observed in this population. Two of the identical isolates were collected on the same day, and the other two were both collected four days later. Within these sampling dates, other more distinct isolates were also collected. Nonetheless, a significant correlation was observed between the distance in sampling date and the proportion of alleles shared between the P. vivax infections in West Timor (Mantel r-test, r = 0.12, P = 0.02). Relative to P. falciparum, little distinction was observed between the P. vivax infections from the other three sites. With the exception of the P. vivax population in West Timor, no significant correlation was observed between the distance in sampling date and the proportion of alleles shared between infections for P. falciparum or P. vivax.

Linkage Disequilibrium

In P. falciparum, LD ranged from an I A S of 0.018 to 0.239 (all P ≤ 0.05) (Table 4). However, after removing duplicate haplotypes, the I A S levels dropped more than two-fold in each of Bangka, Kalimantan, and West Timor.

Table 4. Linkage disequilibrium.

| All infections | Low complexity 1 | Unique haplotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Island | Species | N | I A S | N | I A S | N | I A S |

| Bangka | P. falciparum | 53 | 0.048** | 47 (88%) | 0.062** | 32 (60%) | 0.010 NS |

| P. vivax | 73 | 0.032** | 51 (70%) | 0.034** | 69 (95%) | 0.023** | |

| Kalimantan | P. falciparum | 13 | 0.239 *** | 13 (100%) | 0.239 *** | 7 (54%) | 0.001 NS |

| P. vivax | 7 | -0.003 NS | 6 (86%) | -0.016 NS | 7 (100%) | -0.003 NS | |

| Sumba | P. falciparum | 59 | 0.018* | 53 (91%) | 0.025 * | 54 (93%) | 0.011 NS |

| P. vivax | 37 | 0.017* | 20 (54%) | 0.039 * | 37 (100%) | 0.017 * | |

| West Timor | P. falciparum | 32 | 0.229** | 31 (96.9%) | 0.226** | 16 (50%) | 0.094** |

| P. vivax | 28 | 0.188** | 20 (71%) | 0.263** | 24 (86%) | 0.089 ** |

Only samples with no missing data are included in the analyses. All nine loci were used in all P. vivax populations. In the P. falciparum populations, 8 loci were analysed in Bangka and Sumba, 6 in Kalimantan (exclusion of monomorphic loci TA42 and TA60), and 7 loci in West Timor (exclusion of monomorphic loci TA1).

1 Restricted multi-locus haplotypes from samples with no more than one multi-allelic locus.

NS Not significant (P > 0.05)

* P < 0.05

** P < 0.01

*** P < 0.001.

In P. vivax, significant LD was observed in Bangka, Sumba and West Timor (I A S = 0.017–0.188; all P < = 0.003), but not Kalimantan (I A S = -0.003; P > 0.05). Identical isolates were less frequent than in P. falciparum, and the I A S scores from the unique multi-locus data sets retained equivalent significance to the unfiltered data sets.

Discussion

The heterogeneous epidemiology of malaria in Indonesia provided an opportunity to investigate the comparative transmission dynamics of co-endemic P. vivax and P. falciparum isolates in multiple settings. Using molecular approaches, we demonstrated striking contrasts in diversity and population structure, indicative of varying transmission patterns within and between the two species in different endemicities.

A range of patterns were observed in P. falciparum diversity and structure across the sites. In all populations, polyclonal infection rates (0–20%) were comparable to rates observed in low endemic settings in Southeast Asia [17,23], South America [16,26] and post-intervention sites elsewhere [19,30], suggestive of low transmission and infrequent superinfection. Greater variation was observed in the population diversity (H E = 0.397–0.715). The highest level of diversity was observed in Sumba, reflecting the higher prevalence in this population relative to the other three sites. Whilst the population diversity in Sumba was comparable to levels observed in hyper-holoendemic regions common to Africa [16,27,30], Bangka, Kalimantan and West Timor were more similar to hypo-mesoendemic and unstable endemic regions of South America [16,26] and Southeast Asia [17,23,29]. Relative to Sumba, the latter three populations also exhibited higher levels of LD.

Owing to pooling of P. falciparum samples collected from two regencies (West and Central Bangka), as well as population sub-structure, one possible explanation for the significant LD observed in Bangka was admixture. However, STRUCTURE analysis demonstrated that the majority of isolates in Bangka exhibited predominant ancestry to a single population. In contrast, although sampled from a single administrative district, STRUCTURE analysis indicated that the West Timor population comprised isolates from at least two sub-populations. Thus, admixture may have contributed to the LD observed in West Timor. As demonstrated by the greater than two-fold decline in the index of association (I A S) after accounting for identical multi-locus haplotypes, epidemic expansions also appear to have contributed to the LD observed in West Timor, as well as in Bangka, and Kalimantan. In accordance with epidemic dynamics, clusters of isolates with identical multi-locus haplotypes were prevalent in these populations. Whilst it is possible that the modest number of loci reduced the ability to discriminate between different ‘strains‘, the high diversity observed in Sumba suggests that the resolving capacity was adequate.

In concert, the observed trends in diversity and LD demonstrated a pattern of low, epidemic P. falciparum transmission in Bangka, Kalimantan and West Timor. These trends are consistent with Ministry of Health data on malaria incidence in these regions, where P. falciparum endemicity is characterised as unstable endemic to hypo-mesoendemic. Relative to Sumba, patients from Bangka, Kalimantan and West Timor were older (largely teenagers and young adults), with a higher proportion of males in Bangka and Kalimantan. These demographics might in part reflect at-risk populations such as particular occupational groups, and might explain some of the epidemic transmission dynamics. In contrast to the other populations, the high diversity and linkage equilibrium in Sumba indicated that local P. falciparum transmission remained disconcertingly high and stable in this region. In accordance, the endemicity in Sumba lay at the higher end of the hypo-mesoendemic spectrum, and the P. falciparum patient demographic largely reflected children, with limited gender bias.

As discussed with the specific examples from our data in Indonesia, the heterogeneity in the dynamics of P. falciparum transmission across populations has important implications for elimination. Although Sumba and West Timor are grouped in the same target category for elimination by the national malaria elimination program (elimination by 2020), our data demonstrates that they would likely benefit from different intervention activities. The P. falciparum dynamics in Sumba demonstrate the need for total coverage intervention activities such as broad-ranging distribution of long lasting insecticide-treated bed nets. In contrast, more targeted approaches such as reactive case detection and treatment or indoor residual spraying targeted to households in transmission hot-spots or at-risk populations would be more cost-effective in West Timor [14]. We note that present MOH policies in these regions, based upon passively reported confirmed malaria cases, are consistent with the results of our genetic analysis. With greater sample size, further investigation of both the parasite and patient dynamics should enable identification of at-risk populations for target intervention in West Timor, Bangka and Kalimantan.

Differentiation between the P. falciparum populations was generally high, comparable to levels observed in Malaysian Borneo, where declining transmission and limited migration led to a fragmented parasite population [17]. The declining transmission, distance and island setting should all have facilitated the isolation of the parasite populations assessed here. However, differentiation remained moderate between Sumba and West Timor, highlighting the challenge of parasite introductions into West Timor from the stable transmission setting of Sumba. Indeed, the demonstration of multiple distinct sub-populations by STRUCTURE analysis indicated that other populations such as neighbouring Timor-Leste may present additional reservoirs of infection to West Timor. Identifying the major reservoirs sustaining infection in such populations will be paramount to the success of Indonesia’s elimination campaign. Other global populations will no doubt face similar challenges in the strive toward elimination.

Albeit less marked than in P. falciparum, variation was also observed between sites in P. vivax diversity and structure. Polyclonal infection rates ranged from 23 to 79%, in broad agreement with local API estimates, indicating potential utility in informing on transmission intensity. In the eastern provinces, where patient demographics largely reflected young children, within-host diversity was comparable to high transmission regions of the Pacific [24], Southeast Asia [20,28] and the Horn of Africa [20]. In the western provinces, patient demographics were skewed toward young adults, with a high proportion of males in Bangka. In these populations, within-host diversity was more comparable to post-intervention sites in the Pacific [19] and Malaysia [15]. Relative to the sympatric P. falciparum populations, within-host diversity was consistently higher in P. vivax, in accordance with other studies [18,19,28]. The available evidence suggests that the hypnozoite reservoir and the early, often pre-treatment, development of gametocytes in P. vivax likely explain these observations, and thus have implications for P. vivax control and elimination in other endemic populations.

In contrast to within-host diversity, as demonstrated in other studies across a range of endemic sites across the globe [18–22,24,25,33,50], P. vivax population diversity was high in all four sites (H E = 0.81–0.86), with no apparent correlation with endemicity. Furthermore, the P. vivax populations demonstrated consistently higher diversity than their sympatric P. falciparum populations. The factor(s) responsible for these trends remain unclear. A plausible explanation is that relapsing infections, by enhancing infection complexity, increase the probability that different clones are taken up in the mosquito blood meal, thus promoting the opportunity for new variants to be generated via recombination. However, in temperate regions such as Central China and South Korea, relapse rates are low (20%) and yet P. vivax population diversity remains comparably high [22,25]. Another non-mutually exclusive possibility is that imported infections sustain the diversity of local P. vivax populations [22,67].

The observation of significant LD in P. vivax populations with extensive within-host and population diversity presents a conundrum also encountered in other studies [18,20,21,28,34,67]. Possible explanations for this include a frequently clonal (non-recombining) mode of propagation and/or potential artefact such as selection at or near several of the markers used [28].

In contrast to the P. falciparum populations, the LD patterns in P. vivax did not demonstrate evidence of epidemic transmission in any of the populations investigated. In concert with the observed differences in within-host and population diversity, the differences in LD demonstrated that in several of the endemic settings investigated here, the P. vivax isolates exhibited more frequent and stable transmission than their P. falciparum counterparts. Hence different interventions may be optimal for the respective malaria species in certain settings; local intervention strategies will need to reconcile these differences to ensure adequate impact against all species of malaria. For example, in Bangka, it appears that ongoing interventions have effectively reduced the intensity of local P. falciparum transmission. The current dynamics are moderately unstable with frequent clonal outbreaks amenable to containment by targeted approaches such as reactive case detection and treatment, and indoor residual spraying of case and surrounding households where the predominant vector species behaviour is compatible, prioritizing cases with rapidly emerging outbreak strains. However, the available evidence indicates that targeted approaches would be less effective for the co-endemic P. vivax population. Likely owing to biological differences between the two species such as the hypnozoite stage or comparatively early development of gametocytes in P. vivax versus P. falciparum, the Bangka P. vivax population appeared to have been less impacted by ongoing interventions than the P. falciparum population, displaying more stable transmission with no evidence of clonal outbreaks. These patterns suggest that broad ranging interventions such as large-scale long lasting insecticide-treated bed net coverage are still needed against P. vivax. In addition, effective treatment of the dormant liver stage may be critical to the success of P. vivax intervention efforts.

In contrast to P. falciparum, genetic differentiation was generally low in P. vivax. This observation might reflect the enhanced ‘mobility’ of the parasite afforded by the asymptomatic hypnozoite reservoir, with important implications for the containment of infection, particularly with the rise of anti-malarial drug resistance in P. vivax infection [68]. Alternatively, as discussed by Koepfli and Orjuela-Sanchez, observed trends in P. vivax population diversity and differentiation may in part reflect older, historical events [24,28]. A better understanding of the mechanisms sustaining the diversity, and limiting the observed genetic differentiation between geographically isolated P. vivax populations will be critical to the successful elimination of this species.

Conclusions

Concerted efforts are required to target the major reservoirs of P. vivax infection if malaria elimination is to be successful in co-endemic regions. A better understanding of the local variation in how frequently parasites are transmitted, how focal these transmission events are in time and space, and the ‘mobility’, or potential for parasite spread, can facilitate more optimal malaria intervention strategies. Parasite genotyping can provide useful insights on these dynamics, providing a complementary surveillance tool to the more traditional epidemiological measures, particularly in regions where non-falciparum species circulate.

Supporting Information

1 2010 Census.2 Annual parasite incidence (API) expressed as cases per 1000 population of the administrative region examined (year of investigation and percentage of the population at risk examined are provided in parentheses). Details on the API were provided by Dr Iqbal Elyazar, Malaria Atlas Project.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(CSV)

(CSV)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIFF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients who contributed their samples to the study; the health workers and field teams who assisted with the sample collections; Dr. Iqbal Elyazar and Prof. Simon Hay (Malaria Atlas Project) who provided details on parasite incidence and prevalence maps and Ms. Kylie Mannion (APMEN). We thank the staff who contributed to conducting the field surveys: Provincial District Health Office Bangka-Belitung (Dr. Hendra Kusumajaya, Dr. Helmi Sofi, Dr. Hastuti, Ibu Farida, Mr. Syaifullah and Mr. Fatur), Health Office Bangka Tengah Regency (Ibu Rahmawati), Health Office West Sumba Regency (Drg Bonar Sinaga), Health Office Southwest Sumba Regency (Mr. Yustus Selan), Health Office Ketapang Regency, West Kalimantan (Mr. Khairul Saleh and Mr. Sarim), and Belu, West Timor (Dr. Dedi). We also thank Prof. Sangkot Marzuki and Prof. Herawati Sudoyo (Eijkman Institute, Jakarta) for their support.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The field and laboratory components of the study were funded by an Asia Pacific Malaria Elimination Network (APMEN) Project Grant awarded to RN (No. 107-04). Major funding for APMEN is provided by the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, alongside funds received from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The Malaria Transmission Consortium (UNICEF contract # 43120943) and the Indonesia Ministry of Research and Technology also provided funding for this study. SA, RNP and HT were funded by the Wellcome Trust [Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science (091625) awarded RNP]. SA is also part-funded by APMEN. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Guerra CA, Howes RE, Patil AP, Gething PW, Van Boeckel TP, et al. (2010) The international limits and population at risk of Plasmodium vivax transmission in 2009. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e774 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baird JK (2009) Severe and fatal vivax malaria challenges 'benign tertian malaria' dogma. Ann Trop Paediatr 29: 251–252. 10.1179/027249309X12547917868808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baird JK (2009) Resistance to therapies for infection by Plasmodium vivax. Clin Microbiol Rev 22: 508–534. 10.1128/CMR.00008-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlton JM, Sina BJ, Adams JH (2011) Why is Plasmodium vivax a neglected tropical disease? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1160 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mueller I, Galinski MR, Baird JK, Carlton JM, Kochar DK, et al. (2009) Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect Dis 9: 555–566. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Price RN, von Seidlein L, Valecha N, Nosten F, Baird JK, et al. (2014) Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 14: 982–991. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70855-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Sugiarto P, Warikar N, Kenangalem E, et al. (2008) Multidrug-resistant Plasmodium vivax associated with severe and fatal malaria: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Med 5: e128 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Menard D, Barnadas C, Bouchier C, Henry-Halldin C, Gray LR, et al. (2010) Plasmodium vivax clinical malaria is commonly observed in Duffy-negative Malagasy people. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 5967–5971. 10.1073/pnas.0912496107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mendes C, Dias F, Figueiredo J, Mora VG, Cano J, et al. (2011) Duffy negative antigen is no longer a barrier to Plasmodium vivax—molecular evidences from the African West Coast (Angola and Equatorial Guinea). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1192 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan JR, Stoute JA, Amon J, Dunton RF, Mtalib R, et al. (2006) Evidence for transmission of Plasmodium vivax among a duffy antigen negative population in Western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 75: 575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woldearegai TG, Kremsner PG, Kun JF, Mordmuller B (2013) Plasmodium vivax malaria in Duffy-negative individuals from Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 107: 328–331. 10.1093/trstmh/trt016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cavasini CE, de Mattos LC, Couto AA, Couto VS, Gollino Y, et al. (2007) Duffy blood group gene polymorphisms among malaria vivax patients in four areas of the Brazilian Amazon region. Malar J 6: 167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feachem RG, Phillips AA, Hwang J, Cotter C, Wielgosz B, et al. (2010) Shrinking the malaria map: progress and prospects. Lancet 376: 1566–1578. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61270-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hay SI, Smith DL, Snow RW (2008) Measuring malaria endemicity from intense to interrupted transmission. Lancet Infect Dis 8: 369–378. 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70069-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abdullah NR, Barber BE, William T, Norahmad NA, Satsu UR, et al. (2013) Plasmodium vivax population structure and transmission dynamics in Sabah Malaysia. PLoS One 8: e82553 10.1371/journal.pone.0082553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson TJ, Haubold B, Williams JT, Estrada-Franco JG, Richardson L, et al. (2000) Microsatellite markers reveal a spectrum of population structures in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biol Evol 17: 1467–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anthony TG, Conway DJ, Cox-Singh J, Matusop A, Ratnam S, et al. (2005) Fragmented population structure of plasmodium falciparum in a region of declining endemicity. J Infect Dis 191: 1558–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferreira MU, Karunaweera ND, da Silva-Nunes M, da Silva NS, Wirth DF, et al. (2007) Population structure and transmission dynamics of Plasmodium vivax in rural Amazonia. J Infect Dis 195: 1218–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gray KA, Dowd S, Bain L, Bobogare A, Wini L, et al. (2013) Population genetics of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax and asymptomatic malaria in Temotu Province, Solomon Islands. Malar J 12: 429 10.1186/1475-2875-12-429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gunawardena S, Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Phone-Kyaw M, Pollack RJ, et al. (2010) Geographic structure of Plasmodium vivax: microsatellite analysis of parasite populations from Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82: 235–242. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imwong M, Nair S, Pukrittayakamee S, Sudimack D, Williams JT, et al. (2007) Contrasting genetic structure in Plasmodium vivax populations from Asia and South America. Int J Parasitol 37: 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwagami M, Fukumoto M, Hwang SY, Kim SH, Kho WG, et al. (2012) Population structure and transmission dynamics of Plasmodium vivax in the Republic of Korea based on microsatellite DNA analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1592 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iwagami M, Rivera PT, Villacorte EA, Escueta AD, Hatabu T, et al. (2009) Genetic diversity and population structure of Plasmodium falciparum in the Philippines. Malar J 8: 96 10.1186/1475-2875-8-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koepfli C, Timinao L, Antao T, Barry AE, Siba P, et al. (2013) A Large Reservoir and Little Population Structure in the South Pacific. PLoS One 8: e66041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu Y, Auburn S, Cao J, Trimarsanto H, Zhou H, et al. (2014) Genetic diversity and population structure of Plasmodium vivax in Central China. Malar J 13: 262 10.1186/1475-2875-13-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Machado RL, Povoa MM, Calvosa VS, Ferreira MU, Rossit AR, et al. (2004) Genetic structure of Plasmodium falciparum populations in the Brazilian Amazon region. J Infect Dis 190: 1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mobegi VA, Loua KM, Ahouidi AD, Satoguina J, Nwakanma DC, et al. (2012) Population genetic structure of Plasmodium falciparum across a region of diverse endemicity in West Africa. Malar J 11: 223 10.1186/1475-2875-11-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Orjuela-Sanchez P, Sa JM, Brandi MC, Rodrigues PT, Bastos MS, et al. (2013) Higher microsatellite diversity in Plasmodium vivax than in sympatric Plasmodium falciparum populations in Pursat, Western Cambodia. Exp Parasitol 134: 318–326. 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pumpaibool T, Arnathau C, Durand P, Kanchanakhan N, Siripoon N, et al. (2009) Genetic diversity and population structure of Plasmodium falciparum in Thailand, a low transmission country. Malar J 8: 155 10.1186/1475-2875-8-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rebaudet S, Bogreau H, Silai R, Lepere JF, Bertaux L, et al. (2010) Genetic structure of Plasmodium falciparum and elimination of malaria, Comoros archipelago. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 1686–1694. 10.3201/eid1611.100694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rezende AM, Tarazona-Santos E, Couto AD, Fontes CJ, De Souza JM, et al. (2009) Analysis of genetic variability of Plasmodium vivax isolates from different Brazilian Amazon areas using tandem repeats. Am J Trop Med Hyg 80: 729–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schousboe ML, Ranjitkar S, Rajakaruna RS, Amerasinghe PH, Konradsen F, et al. (2014) Global and local genetic diversity at two microsatellite loci in Plasmodium vivax parasites from Asia, Africa and South America. Malar J 13: 392 10.1186/1475-2875-13-392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van den Eede P, Erhart A, Van der Auwera G, Van Overmeir C, Thang ND, et al. (2010) High complexity of Plasmodium vivax infections in symptomatic patients from a rural community in central Vietnam detected by microsatellite genotyping. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82: 223–227. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van den Eede P, Van der Auwera G, Delgado C, Huyse T, Soto-Calle VE, et al. (2010) Multilocus genotyping reveals high heterogeneity and strong local population structure of the Plasmodium vivax population in the Peruvian Amazon. Malar J 9: 151 10.1186/1475-2875-9-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schultz L, Wapling J, Mueller I, Ntsuke PO, Senn N, et al. (2010) Multilocus haplotypes reveal variable levels of diversity and population structure of Plasmodium falciparum in Papua New Guinea, a region of intense perennial transmission. Malar J 9: 336 10.1186/1475-2875-9-336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arnott A, Barry AE, Reeder JC (2012) Understanding the population genetics of Plasmodium vivax is essential for malaria control and elimination. Malar J 11: 14 10.1186/1475-2875-11-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization; (2013) World Malaria Report 2013. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Wuwung M, Brockman A, et al. (2007) Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 101: 351–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sumawinata IW, Bernadeta, Leksana B, Sutamihardja A, Purnomo, et al. (2003) Very high risk of therapeutic failure with chloroquine for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax malaria in Indonesian Papua. Am J Trop Med Hyg 68: 416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Elyazar IR, Hay SI, Baird JK (2011) Malaria distribution, prevalence, drug resistance and control in Indonesia. Adv Parasitol 74: 41–175. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385897-9.00002-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sulistyaningsih E, Fitri LE, Loscher T, Berens-Riha N (2010) Diagnostic difficulties with Plasmodium knowlesi infection in humans. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 1033–1034. 10.3201/eid1606.100022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Figtree M, Lee R, Bain L, Kennedy T, Mackertich S, et al. (2010) Plasmodium knowlesi in human, Indonesian Borneo. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 672–674. 10.3201/eid1604.091624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareonviriyaphap T, et al. (2012) A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors 5: 69 10.1186/1756-3305-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malaria Atlas Project website. Available: www.map.ox.ac.uk. Accessed 23rd February, 2015.

- 45. Gething PW, Patil AP, Smith DL, Guerra CA, Elyazar IR, et al. (2011) A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malar J 10: 378 10.1186/1475-2875-10-378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Moyes CL, Smith DL, Battle KE, et al. (2012) A long neglected world malaria map: Plasmodium vivax endemicity in 2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1814 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN (1993) Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of a high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol 58: 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boonma P, Christensen PR, Suwanarusk R, Price RN, Russell B, et al. (2007) Comparison of three molecular methods for the detection and speciation of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J 6: 124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Anderson TJ, Su XZ, Bockarie M, Lagog M, Day KP (1999) Twelve microsatellite markers for characterization of Plasmodium falciparum from finger-prick blood samples. Parasitology 119 (Pt 2): 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Munasinghe A, Barnwell JW, Collins WE, et al. (2008) Extensive microsatellite diversity in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Gene 410: 105–112. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koepfli C, Mueller I, Marfurt J, Goroti M, Sie A, et al. (2009) Evaluation of Plasmodium vivax genotyping markers for molecular monitoring in clinical trials. J Infect Dis 199: 1074–1080. 10.1086/597303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Excoffier L, Lischer HE (2010) Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 10: 564–567. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hedrick PW (2005) A standardized genetic differentiation measure. Evolution 59: 1633–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14: 2611–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rosenberg NA (2004) Distruct: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Molecular Ecology Notes 4: 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haubold B, Hudson RR (2000) LIAN 3.0: detecting linkage disequilibrium in multilocus data. Linkage Analysis. Bioinformatics 16: 847–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bowcock AM, Ruiz-Linares A, Tomfohrde J, Minch E, Kidd JR, et al. (1994) High resolution of human evolutionary trees with polymorphic microsatellites. Nature 368: 455–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K (2004) APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20: 289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dray S, Dufour AB (2007) The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software 22: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Amodu OK, Oyedeji SI, Ntoumi F, Orimadegun AE, Gbadegesin RA, et al. (2008) Complexity of the msp2 locus and the severity of childhood malaria, in south-western Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 102: 95–102. 10.1179/136485908X252340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Beck HP, Felger I, Huber W, Steiger S, Smith T, et al. (1997) Analysis of multiple Plasmodium falciparum infections in Tanzanian children during the phase III trial of the malaria vaccine SPf66. J Infect Dis 175: 921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kyes S, Harding R, Black G, Craig A, Peshu N, et al. (1997) Limited spatial clustering of individual Plasmodium falciparum alleles in field isolates from coastal Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 57: 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Roper C, Richardson W, Elhassan IM, Giha H, Hviid L, et al. (1998) Seasonal changes in the Plasmodium falciparum population in individuals and their relationship to clinical malaria: a longitudinal study in a Sudanese village. Parasitology 116 (Pt 6): 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zwetyenga J, Rogier C, Tall A, Fontenille D, Snounou G, et al. (1998) No influence of age on infection complexity and allelic distribution in Plasmodium falciparum infections in Ndiop, a Senegalese village with seasonal, mesoendemic malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 59: 726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gunawardena S, Ferreira MU, Kapilananda GM, Wirth DF, Karunaweera ND (2014) The Sri Lankan paradox: high genetic diversity in Plasmodium vivax populations despite decreasing levels of malaria transmission. Parasitology 141: 880–890. 10.1017/S0031182013002278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Price RN, Auburn S, Marfurt J, Cheng Q (2012) Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of drug-resistant Plasmodium vivax. Trends Parasitol 28: 522–529. 10.1016/j.pt.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1 2010 Census.2 Annual parasite incidence (API) expressed as cases per 1000 population of the administrative region examined (year of investigation and percentage of the population at risk examined are provided in parentheses). Details on the API were provided by Dr Iqbal Elyazar, Malaria Atlas Project.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(CSV)

(CSV)

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIFF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.