Abstract

Objective

Grand-parenting is an important social role but how adults with a history of depression experience grand-parenting is unknown; we describe grand-parenting experiences reported by an ethnically-diverse sample of adults with a history of depression.

Method

Mixed-methods study using semi-structured interviews of adults at 10-year follow-up and quantitative data collected over 9 years from 280 systematically-sampled participants from a longitudinal, multi-site trial of quality-improvement interventions for depressed primary care patients; of 280, 110 reported noncustodial grand-parenting experiences.

Results

Of 110 adults reporting grand-parenting experiences, 90 (82%) reported any positive experience such as special joy; 57 (52%) reported any stressful experience such as separation; 27 (34%) reported mixed experiences. Adults with chronic or recent depression were significantly more likely than their respective counterparts to report any stressful experience (p<0.05). There was no significant association between depression status and reporting a positive experience.

Conclusion(s)

Grand-parenting was a highly salient and positive experience as reported by ethnically-diverse adults 10 years after being identified as depressed in primary care. Depression status was associated with reporting stressful but not positive experiences. Specific themes underlying positive and stressful experiences may have implications for developing strategies to enhance quality of life for adults with a history of depression who are grandparents.

Keywords: depression, older adults, grand-parenting, mixed-methods, minority and diverse populations

Introduction

Depression is among the most common and disabling conditions affecting older adults.[1, 2] Depression is often chronic or recurrent[3, 4] and is associated with increased risk of morbidity, decreased physical and social functioning, and diminished health-related quality of life.[5] Whereas social isolation and loneliness are known risk factors for developing depression,[6–8] participation in social activities has a protective effect on depression.[9, 10]

For many adults, grand-parenting is a crucial social activity and role.[11–13] Past work has demonstrated a positive association between grand-parenting and grandparents’ psychological well-being and quality of life.[14, 15] An extensive and separate literature exists on the experience and mental health impact of custodial grand-parenting,[16–18] which is regarded as distinct from and more similar to parenting than non-custodial grand-parenting (henceforth referred to as grand-parenting). Few studies have examined the experience of grand-parenting among adults with a history of depression. Given the pervasive negative thinking and poor socialization that often accompany depression, adults with a history of depression may not experience the positive aspects generally associated with grand-parenting. Knowing more about how adults with a history of depression experience grand-parenting would clarify whether grand-parenting experiences are positive or stressful in this population, and may inform efforts to develop patient-centered approaches to care for adults who are grandparents and have a history of depression. Such information could have important implications for clinicians working with adults with a history of depression, such as informing how to structure supportive family relationships, or developing opportunities for positive experiences.

The opportunity to address these issues was afforded by a long-term continuation phase of Partners in Care (PIC), a group-level randomized trial of implementation of quality improvement for depression compared to enhanced usual care for depressed primary care patients. The main trial included follow-up over 5 years post intervention implementation. A separate continuation study was conducted at 9–10 year follow-up that included a quantitative survey similar to those included periodically over the course of the main study, followed by semi-structured interviewing about the experience of dealing with depression and stressful and positive events. Without being prompted about grand-parenting experiences, many adults discussed those experiences at long-term follow-up. This study analyzes grand-parenting experiences overall and as a function of gender, ethnicity, and history of depression. We hypothesized that grand-parenting would be largely experienced positively, across gender and ethnic groups, but might be more negatively viewed by those still struggling with depression. We hypothesized that grandparent experiences might be perceived as having therapeutic benefit for depression.

Methods

Data Source

We employed quantitative data from the main PIC study, and both quantitative and qualitative data from the 9–10 year continuation study based on PIC. PIC was a group-level randomized controlled trial of quality-improvement (QI) interventions for depression in primary care.[19] Briefly, clinics in 4 geographic areas were randomized to a control group of enhanced usual care or to one of two QI programs for depression featuring team management, provider and patient education, case management plus enhanced resources for either medication management (QI-Meds) or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (QI-Therapy). Patients were identified as having probable depressive disorder based on scoring positive on a depression screener at the time of an office visit after practices had intervention training. The parent study included quantitative surveys at baseline, and 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-, and 60-month follow-up after study enrollment. The QI programs improved participating adults’ depressive symptoms and quality of care for depression over the initial 2 years of follow-up and reduced disparities in depression outcomes among African-Americans and Latinos relative to whites at 6- and 60-month follow-up. Based on these findings, a continuation study was funded for 9–10 year follow-up including a quantitative survey 9 years after enrollment (Stage 1) followed by 3 semi-structured interviews 10 years after enrollment among a stratified, random sample (Stage 2). The qualitative sample included all minority participants and a random sample of whites, matched by site, clinic intervention assignment and gender to the minority sample. The continuation study was designed to develop explanatory mechanisms for the findings of long-term reduction in ethnic disparities in depression outcomes. Our study focused on the qualitative interview sample and data but also employed quantitative data from that sample from earlier phases of the PIC study.

Qualitative Interviewing – Methods and Instrument

The qualitative data were from 3 semi-structured recorded telephone interviews conducted over 3 months per Stage 2 participant. The interviews were conducted in English or Spanish by trained interviewers. Each interview began with a series of event screeners in which participants were asked if they had in the previous 30 days experienced the following events: depressive symptoms, antidepressant medication use, help-seeking for emotional, personal and/or mental health problems, stressful events, proactive coping, and/or positive life events. Events identified were explored in event modules. Event modules followed a grounded-theory approach by using open-ended questioning to encourage participants to describe freely what was meaningful to them about that event.[20] Participants were first asked a general question (“Please tell me about that experience. Tell me about the events that led up to it, what happened during the experience, and the effect it had for you and the problems you were having”), followed as needed by probes (i.e., “What else was going on in your life,” “Who was involved,” “What were you thinking,” “How did you feel,” “What did you do,” “How was it similar or different to situations in the past”).

Participants were asked to participate in 3 interviews to maximize exploration of as many events as possible. Not all participants completed all 3 interviews. Interviews were limited to 60 minutes to minimize participant burden. Interviewers prioritized asking about events that had not been discussed in prior interviews. Thus, not all events with a positive screener in a given interview were explored in that particular interview. The series of interviews each participant completed were considered as one narrative per participant.

Data from these interviews included notes interviewers typed into a computer using Computer Aided Telephone Interviewing (CATI) software while conducting the interview. Immediately afterwards, interviewers reviewed notes while listening to the audio recording to improve note quality. Notes were reviewed for accuracy by the PIC study team. Notes were transferred to a qualitative software program (ATLAS.ti) to facilitate data management and analysis. The RAND institutional review board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained.

Analytic Sample

Of the 750 participants who completed Stage 1 of the continuation study, all African-Americans (n=46) and Latinos (n=205), and a matched subsample (n=108) of whites were invited to participate in Stage 2. Thirty-seven African-Americans, 157 Latinos and 86 whites completed at least one interview. Across the 3 groups, 259 completed at least 2 interviews, 250 completed all 3. For analyses of having reported any grand-parenting experience, the analytic sample comprised the 280 participants who completed at least one interview.

The analytic sample employed to describe grand-parenting experiences included participants completing at least one qualitative interview who also spontaneously described at least one grand-parenting experience. We excluded participants who described an experience with someone else’s grandchild or who described having custodial grand-parenting responsibilities, defined as participant self-report of living with the grandchild without the grandchild’s parent(s), raising the grandchild, and/or having legal custody of the grandchild or child protective services transfer the care of the grandchild to them.

Participants were not specifically prompted to talk about grand-parenting by interviewers. We employed the word search function in ATLAS.ti to systematically identify every spontaneously mentioned grand-parenting experience. We examined all text within the interview notes using the search term “gran*” to locate text containing any of the following: grandchild, grandson(s), granddaughter(s), grandkid(s), grand(s), grandchildren, grandparent(s), grandfather, grandmother, grandpa, grandma, granny, as well as a word search for grandchildren equivalents (e.g., “son’s son/daughter,” “daughter’s daughter/son”). The same process was applied to the Spanish-language interviews (“abuel*,” “niet*”). Interview notes flagged by the word search were reviewed to ensure that the text recounted a grand-parenting experience.

Of the 280 participants who completed at least one qualitative interview, we excluded 151 who did not mention a grand-parenting experience, 2 who mentioned only experiences with someone else’s grandchild(ren) and 17 who described custodial grand-parenting experiences. The remaining 110 (39% of participants completing at least one qualitative interview) spontaneously described a grand-parenting experience and were included in subsequent analyses.

Qualitative data analysis

Data were analyzed using grounded theory methodology, which employs thematic content and constant comparative methods to identify the range and salience of themes characterizing the phenomenon being studied.[20] One investigator (AI), a bilingual general internist, broadly coded text segments comprising participants’ descriptions of grand-parenting experiences as positive and/or stressful. A positive code was assigned to text in which participants described grand-parenting experiences with pleasant or enjoyable features. A stressful code was assigned to text in which participants described grand-parenting experiences that were troubling or distressing. Two investigators independently examined text from 10% of the sample (n=11 participants). Inter-coder agreement for the positive/ stressful codes was high (κ=0.83).

Three investigators – a general internist (AI), a psychologist (JM) and a psychiatrist (KW) – identified themes in the coded text. As a group, the investigators compared the text within and across participants to iteratively refine a set of themes that described the types of positive and stressful experiences participants reported. In a series of discussions over time, the investigators: identified thematic patterns in the positive and stressful experiences, discussed the defining features of each theme and its accompanying text, revised the theme list and theme definitions, searched the data for disconfirming and outlying examples that could be used to refine and expand the thematic definitions, and identified a list of themes that captured the range of experiences participants described. The themes were defined in a codebook that included representative and extreme examples from the text for each theme. One investigator (AI) employed the codebook to systematically assign relevant theme(s) to participants’ grand-parenting experiences.

Other Study Measures

To describe the sample, we included measures (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational level) from the PIC study screener used to identify eligible participants at baseline. PIC intervention status (i.e., usual care, QI-medications, QI-therapy) was included as a design variable; we did not expect intervention status differences in the spontaneous reporting of grand-parenting experiences or the kinds of grand-parenting experiences described. We included a measure (i.e., health insurance status) from Stage 1 of the continuation study, and measures (i.e., age, interview completed in Spanish) from Stage 2.

Chronic depression was defined as having probable depression in at least half of the 6 quantitative surveys conducted over the 9 years following PIC enrollment. Probable depression was defined as having at least 1 week of depressed mood or loss of interest in pleasurable activities in the last 30 days, plus 2 weeks or more of the same symptoms in the last 6 months. [19] Recent depression was defined as reporting depressive symptoms and/or anhedonia in the prior 30 days on the event screener in at least 1 of the 3 qualitative interviews (i.e., answering yes to at least one of the following questions: “In the last month, did you have a period of one week or more when nearly every day you felt sad, empty or depressed for most of the day? You lost interest in most things like work, hobbies, and other things you usually enjoyed?”).

To describe participants broadly by the kinds of grand-parenting experiences they reported (i.e., positive and or stressful) we created 3 broad, non-mutually exclusive categories: any positive, any stressful, and both positive and stressful grand-parenting experiences.

Quantitative data analysis

We employed bivariate analysis techniques to compare participants who did and did not spontaneously describe a grand-parenting experience. We presented the mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables. These analyses used t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables with an adjustment that the p-value was calculated for Fisher’s exact test when one or more of the cells had an expected frequency of five or less.[21] We then utilized Chi-square tests to examine the association between depression status and: 1) the 3 broad categories of grand-parenting experiences participants reported, and 2) the 13 specific themes participants’ grand-parenting experiences represented.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants who described grand-parenting experiences were older, more likely to have been married at PIC study onset and less likely to have completed high school than participants who did not describe grand-parenting experiences (Table 1). Participants who did and did not describe grand-parenting experiences did not differ by PIC parent study quality improvement intervention or control status, or by chronic or recent depression status. The analytic sample of participants who described grand-parenting experiences (N=110) was 82% female, 60% Latino, mean age was 60 years (SD=11 years), 48% had chronic depression, and 66% had recent depression (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Partners in Care (PIC) continuation study participants who completed semi-structured interviewing

| Characteristic | Total (N=263) |

Participants who described grand- parenting experiences (n=110) |

Participants who did not describe grand- parenting experiences (n=153) |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD, years | 53±13 | 60±11 | 48±12 | <0.001 |

| Female gendera | 212 (80.6) | 90 (81.8) | 122 (79.7) | 0.674 |

| Ethnicitya | 0.548 | |||

| African-American | 31 (11.8) | 11 (10.0) | 20 (13.1) | |

| Latino | 148 (56.3) | 66 (60.0) | 82 (53.6) | |

| White | 84 (31.9) | 33 (30.0) | 51 (33.3) | |

| Marrieda | 141 (53.6) | 71 (64.5) | 70 (45.8) | 0.003 |

| Completed high schoola | 215 (81.7) | 82 (74.5) | 133 (86.9) | 0.010 |

| Interview completed in Spanish | 37 (14.1) | 16 (14.5) | 21 (13.7) | 0.850 |

| Had health insurance | 230 (87) | 99 (90.0) | 131 (86.2) | 0.352 |

| Had chronic depressionb | 126 (48.8) | 51 (47.7) | 75 (49.7) | 0.751 |

| Had recent depressionc | 164 (65.9) | 70 (66.0) | 94 (65.7) | 0.960 |

| PIC study intervention status a | 0.949 | |||

| Usual care | 86 (32.7) | 35 (31.8) | 51 (33.3) | |

| QI-meds | 77 (29.3) | 32 (29.1) | 45 (29.4) | |

| QI-therapy | 100 (38.0) | 43 (39.1) | 57 (37.3) |

Notes: SD = standard deviation. All values given are n (%) unless otherwise noted. Bivariate analyses used t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Variables were assessed at the time of PIC parent study enrollment. All other variables were assessed in the two-stage continuation study to PIC that was conducted over years 9 and 10 after PIC study enrollment.

Chronic depression defined having probable depression in at least half of the 6 quantitative surveys conducted over the 9 years following PIC enrollment; item was missing for 3 participants who described grand-parenting experiences and 2 participants who did not describe grand-parenting experiences.

Recent depression was defined as having screened positive for depressive symptoms and/or anhedonia for one week or more in the last month in at least 1 of the 3 qualitative interviews conducted as part of the second-stage of the PIC continuation study; item was missing for 4 participants who described grand-parenting experiences and 10 participants who did not describe grand-parenting experiences.

Grand-parenting Experiences

We identified 9 positive themes, which were organized into 3 domains (i.e., affective states; behavioral and cognitive activation; depression-related outcomes), and 4 stressful themes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grand-parenting experiences – positive and stressful themes and subthemes and sample quotations

| Themes and subthemes | Sample quotations |

|---|---|

| POSITIVE THEMES | |

| Affective states | |

| Special joy | “My granddaughter is the apple of my eye. She’s the joy of my life. Seeing her smiling face and holding her hand made me feel like I was in heaven.” (67-year old Latino with recent depression) “My grandson’s such a joy! I’ve had great experiences before, but you can’t compare them because having a grandchild is not the same kind of joy.” (52-year old African-American woman with recent depression) |

| Sense of personal meaning | “My grandchildren come to my house every day. It makes me feel as if I belong. As if I’m needed.” (59-year old Latina without chronic or recent depression) “Taking care of my grandson has given me great satisfaction because I didn’t have the chance to enjoy my own children when they were young. I had to work. I’m experiencing things I never got to experience with my own children.” a (59-year old Latina without chronic or recent depression) |

| Love and affection | “My grandson gave me lots of hugs and kisses spontaneously – that was the best feeling of all. I felt like a million bucks. It felt wonderful.” (77-year old African-American woman with chronic and recent depression) “The love of granddaughters is unconditional. They don’t care if grandma’s robe has a hole or has not teeth. They tell you you are beautiful and they love you. Your kids are critical because your presence represents them in a way. I don’t have to be at my best with my grandkids.” (54-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) |

| Behavioral activation | |

| Pleasurable activity | “When my grandson was here, we’d play games and fish. It was really busy for me – I didn’t have to look for something to do. My grandson got me out of the house and kept me busy.” (54-year old Latino with chronic and recent depression) “My two grandkids and I spent the day together. We all made tamales together. I felt good. I felt happy.” (54-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) |

| Improved self-care | “I’ve been going regularly for my mammogram, colonoscopy. It’s about me realizing I have 4 grandchildren and I want to be able to run around with them. I do not want to be the one sitting in the chair all the time.” (59-year old African-American woman with chronic depression) “Before I didn’t care and wouldn’t take care of myself. My grandkids have helped me to change my perspective. I want to be able to do things with my grandkids – walk, talk, see them, play, go to the beach. Diabetics can lose their vision and limbs. Now I have made the decision to live and as well and as happily as I can.” (58-year old Latina without chronic or recent depression) |

| Future orientation | “I’m looking forward to going to New York to see my new grandbaby. I can see a light ahead.” (48-year old Latina without chronic or recent depression) “My grandkids are what keeps me going.” (57-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) |

| Outcomes | |

| Explicit depression relief | “I try to do things to snap out of it when I’m feeling down. When I feel depressed, I go to visit my daughter. My grandkids make me feel better.” (60-year old Latina with recent depression) “My psychiatrist always asks me if I have any suicidal thoughts. As bad as I feel, I always say no. Because of my grandkids, I’m not ready to go nowhere.” (59-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) “I feel like my granddaughter is the best therapy for me.” (67-year old Latina with recent depression) “The 6 days with my granddaughter have been better for me than my Prozac.” (42-year old Latina with chronic depression) |

| Reduced loneliness | “When I feel very lonely, I sometimes have my oldest granddaughter come and spend the night with me. She’s like my little sidekick.” (49-year old white woman with chronic and recent depression) “I find spending time with my granddaughter helps me with my loneliness.” (59-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) |

| Enhanced social relationships Improved family ties | “Forcing my husband to hold our granddaughter mended the relationship with my husband and son. That baby has just been a miracle. It was a bad situation and the baby was the band-aid.” (59-year old Latina with recent depression) “The baby brings me closer together with my son.” (70-year old Latino without chronic or recent depression) |

| Enhanced interactions with friends | “I talk to my friends about my grandson or my granddaughter.” (68-year old African-American woman without chronic or recent depression) “We talked about our grandkids. I enjoyed the experience because it wasn’t about me, and it wasn’t about the [wheel]chair, and it wasn’t about the arthritis.” (55-year old white woman without chronic or recent depression) |

| STRESSFUL THEMES | |

| Geographic separation | “It hurts that I can’t be near my grandkids.” a (64-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) “Now I see my grandkids every day. Then you cut it down to 3 or 4 times if I’m lucky? Not being able to see them every day [once they move away] will be heartbreaking.” (59-year old African-American woman with chronic depression) |

| Strained family relationships | “I was always taking care of my grandchildren. As they got older, their mom didn’t let them come over to my house anymore. It hurts and makes me feel alone. I have to back off. I feel that contributes to my depression.” (65-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) “My son-in-law told me I’ll never get to see my grandkids again if I continue to disapprove of him. I don’t want to cut off ties but I can’t take on anymore hurt.” (54-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) |

| Grandchildren’s physical/behavioral health problems | “My granddaughter and grandson are both in jail, and this makes me feel angry, sad. And really depressed.” (77-year old white woman with neither chronic nor recent depression) “My grandson [with attention-deficit disorder] is doing worse at school and causing problems. He breaks my heart. I hurt for him.” (59-year old Latina with recent depression) |

| Grandparents’ physical health problems | “My left sight is almost blind. Not being able to see gets me depressed about not being able to see my grandkids.” (54-year old Latina with chronic and recent depression) “The ripple effects of losing my mobility is something that bothers me. I can’t play with my grandson on the floor like he wants me to.” (55-year old white woman without chronic or recent depression) |

Note: Spanish translations by author (AI).

Quote originally in Spanish: “Me ha dado mucha satisfacción poder cuidar a mi nieto porque no tuve la oportunidad de disfrutar a mis propios hijos cuando eran chicos. Tenia que trabajar. Estoy viviendo cosas que con ellos no vivi.”

Quote originally in Spanish: “Me duele que no puedo estar cerca de mis nietos.”

Positive Themes

Themes related to affective states

Three themes were related to affective states, or participants’ emotional experience of the grandparent-grandchild interaction. Special joy emerged from descriptions of the exceptional and exuberant delight participants experienced in association with grand-parenting. Sense of personal meaning encompassed grand-parenting experiences in which participants reported feeling useful, needed, productive, and/or proud; it also included experiences described as representing a psychological “second chance” to be a parent. Love and affection emerged from participants’ reports of grand-parenting experiences associated with experiencing physical affection and/or feeling loved.

Themes related to behavioral and cognitive activation

Three themes were related to states consistent with behavioral activation goals. Pleasurable activity emerged from participants’ descriptions of grand-parenting experiences associated with enjoyable and pleasantly distracting activities. Improved self-care included descriptions of grand-parenting experiences in which participants reported taking better care of themselves and their health (e.g., adhering to medications for chronic illnesses, engaging in preventive health care). Future orientation encompassed descriptions of grand-parenting experiences associated with reports of optimism, a sense of legacy and looking forward to future grandparent-grandchild interactions.

Themes related to depression-related outcomes

Grand-parenting experiences to which participants ascribed direct therapeutic benefit were represented by the theme explicit depression relief. It included descriptions of grand-parenting experiences in which participants’ reported being distracted from their depression, feeling less depressed, being motivated to overcome depression, resisting suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and coping with depressive symptoms and stressful situations contributing to their depression. Explicit depression relief included grand-parenting experiences that were described as having direct attributes of psychological and pharmacologic treatments for depression. Reduced loneliness included descriptions of grand-parenting experiences in which participants reported being less alone and/or feeling less lonely. Enhanced social relationships emerged from reports of grand-parenting experiences associated with strengthened social ties with family and friends; it included circumstances in which prior conflict was resolved and/or social contact was enhanced as a result of participants’ grand-parenting experiences.

Stressful Themes

Stressful themes were associated with contextual factors and stressors that complicated and placed strain on the grandparent-grandchild relationship rather than with direct conflict between participants and their grandchildren. Geographic separation included descriptions of grand-parenting experiences in which participants reported feeling sad, upset or depressed about not being able to see and spend time with their grandchildren because of geographic separation. Strained family relationships emerged from participants’ descriptions of conflict with their adult children, which participants reported interfered with their desire and ability to interact with their grandchildren. Grandchildren’s physical/behavioral health problems was defined by grand-parenting experiences in which participants described feeling sad or distressed about their grandchildren’s health struggles and/or an inability to help able. Grandparents’ physical health problems emerged from grand-parenting experiences in which participants described a physical ailment (e.g., chronic pain, visual impairment, disability) that interfered with their ability and desire to interact with their grandchildren.

Bivariate Associations

Of the 110 participants who spontaneously described grand-parenting experiences, the majority (82%; n=90) reported grand-parenting experiences with any positive feature (Table 3). Fifty-two percent (n=57) reported grand-parenting experiences with any stressful feature; 34% (n=27) reported experiences with both positive and stressful features. The likelihood of reporting grand-parenting experiences with either any positive or any negative feature was not significantly associated with participant gender, age or race/ethnicity (online Appendix Table A1). Participants with chronic depression and those with recent depression were significantly more likely than their respective counterparts to report grand-parenting experiences with any stressful feature (p<0.05). There was no significant association between depression status and the likelihood of reporting an experience with any positive features.

Table 3.

Number of participants in each grand-parenting experience category and who described each grand-parenting experience theme, by participant depression status

| Analytic sample (N=110) |

Chronic depressiona |

Recent depressionb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=56) |

Yes (n=51) |

p- value |

No (n=36) |

Yes (n=70) |

p- value |

||

| CATEGORY | |||||||

| Grand-parenting experience with any positive features | 90 (81.8) | 44 (78.6) |

44 (86.3) |

0.298 | 31 (86.1) |

55 (78.6) |

0.437 |

| Grand-parenting experience with any stressful features | 57 (51.8) | 24 (42.9) |

32 (62.7) |

0.04 | 13 (36.1) |

42 (60.0) |

0.025 |

| Grand-parenting experience with both positive and stressful features | 37 (33.6) | 12 (21.4) |

25 (49.0) |

0.003 | 8 (22.2) | 27 (38.6) |

0.090 |

| POSITIVE THEMES | |||||||

| Special joy | 16 (14.5) | 7 (12.5) | 8 (15.7) | 0.635 | 5 (13.9) | 11 (15.7) |

1c |

| Sense of personal meaning | 24 (21.8) | 10 (17.9) |

14 (27.5) |

0.235 | 10 (27.8) |

13 (18.6) |

0.276 |

| Love and affection | 8 (7.3) | 2 (3.6) | 5 (9.8) | 0.254c | 0 (0) | 8 (11.4) | 0.049c |

| Pleasant activity | 65 (59.1) | 32 (57.1) |

33 (64.7) |

0.424 | 21 (58.3) |

40 (57.1) |

0.907 |

| Improved self-care | 4 (3.6) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (5.90) | 0.105c | 3 (8.3) | 1 (1.4) | 0.112c |

| Future orientation | 13 (11.8) | 8 (14.3) | 5 (9.8) | 0.562c | 6 (16.7) | 6 (8.6) | 0.213 |

| Explicit depression relief | 28 (25.5) | 8 (14.3) | 19 (37.3) |

0.006 | 4 (11.1) | 23 (32.9) |

0.018c |

| Reduced loneliness | 6 (5.5) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (9.8) | 0.101c | 2 (5.6) | 4 (5.7) | 1c |

| Enhanced social relationships | 9 (8.2) | 8 (14.3) | 1 (2.0) | 0.033c | 4 (11.1) | 4 (5.7) | 0.440c |

| STRESSFUL THEMES | |||||||

| Geographic separation | 13 (11.8) | 4 (7.1) | 9 (17.6) | 0.139c | 4 (11.1) | 9 (12.9) | 1c |

| Strained family relationships | 21 (19.1) | 13 (23.2) |

7 (13.7) | 0.209 | 4 (11.1) | 16 (22.9) |

0.193c |

| Grandchildren’s physical/behavioral health problems | 24 (21.8) | 9 (16.1) | 15 (29.4) |

0.098 | 6 (16.7) | 18 (25.7) |

0.292 |

| Grandparent’s physical health problems | 5 (4.5) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (5.9) | 0.668c | 1 (2.8) | 3 (4.3) | 1c |

Notes all values given are are n (%). P-values calculated using Chi-square test unless otherwise noted.

Item was missing for 3 participants.

Item was missing for 4 participants.

p-value calculated using Fisher’s Exact Test.

No significant differences in specific theme frequency were found by participant gender, age or race/ethnicity (online Appendix Table A1). Participants with chronic depression or with recent depression were significantly more likely than their respective counterparts to describe a grand-parenting experience associated with explicit depression relief (p<0.05) (Table 3) while those with recent depression were significantly more likely than those without to describe a grand-parenting experience that reflected the theme of love and affection (p<0.05). Participants with chronic depression were significantly less likely than their counterparts to report a grand-parenting experience associated with enhanced social relationships (p<0.05).

Discussion

Using long-term qualitative and quantitative data from the PIC study, we found that grand-parenting was a highly salient and predominantly positive experience for many adults with a history of depression. Without being asked specific probes about grand-parenting, participants spontaneously and frequently mentioned grand-parenting experiences with similar likelihood regardless of gender, race/ethnicity, or depression history. Contrary to our predictions, participants with chronic depression or recent depression who reported grand-parenting experiences were as likely as their counterparts to describe a positive grand-parenting experience. Specifically, grand-parenting was described as affording special joy, a sense of meaning, love and affection, pleasurable activity, improved self-care, future orientation, and enhanced social relationships. The exuberant emotion with which participants described grand-parenting was striking and was present for those with and without chronic or recent depression.

Many participants explicitly described grand-parenting as providing depression relief and in therapeutic terms. The positive themes that emerged from participants’ descriptions of grand-parenting experiences are consistent with the cognitive and behavioral processes known to improve depression within cognitive behavioral therapy. Participants described time with their grandchildren as a pleasurable activity, as well as a positive social interaction.[22] In addition, participants described the experience of grandparenting as prompting them to engage in cognitive reframing. For example, one grandparent realized began taking better care of herself because she now believed that her grandchild motivated her to remain healthy in order to maintain their relationship. These findings clearly have implications for the clinical field. For example, exploring the extent to which older adults might become involved with their grandchildren in order to decrease their depression could be an important tool. Because some grandparents found their role as stressful, an initial evaluation of the relationship would be important.

We found that participants reported feeling and being less alone in association with grand-parenting experiences. Loneliness in older adults is common and is associated with adverse physical and mental health consequences.[23] Among older adults, loneliness is associated with depression, though whether it is a cause or an effect of depression remains unclear.[24, 25] Previous investigators have suggested that intervention strategies targeting loneliness, understood as an emotional condition and/or perceived or actual social isolation,[26] may potentially improve older adult functioning, mental health and quality of life. Our findings may inform the clinical care of older adults with depression by identifying potentially meaningful psychosocial interactions for further discussion to target loneliness among older adults.

Another important finding was that stressful experiences associated with grand-parenting were more likely among participants with a history of chronic or recent depression. Geographic separation, strained family relationships, grandchildren’s health problems, and grandparents’ physical health problems were associated with stressful grand-parenting experiences. Some participants described their own coping strategies for these challenges, such as using video-chat and/or taking trips to see their grandchildren. Identifying sources of grand-parenting strain and promoting effective coping strategies, such as activating social supports and using diverse communication resources, may be helpful activities for health providers caring for adults with a history of depression.

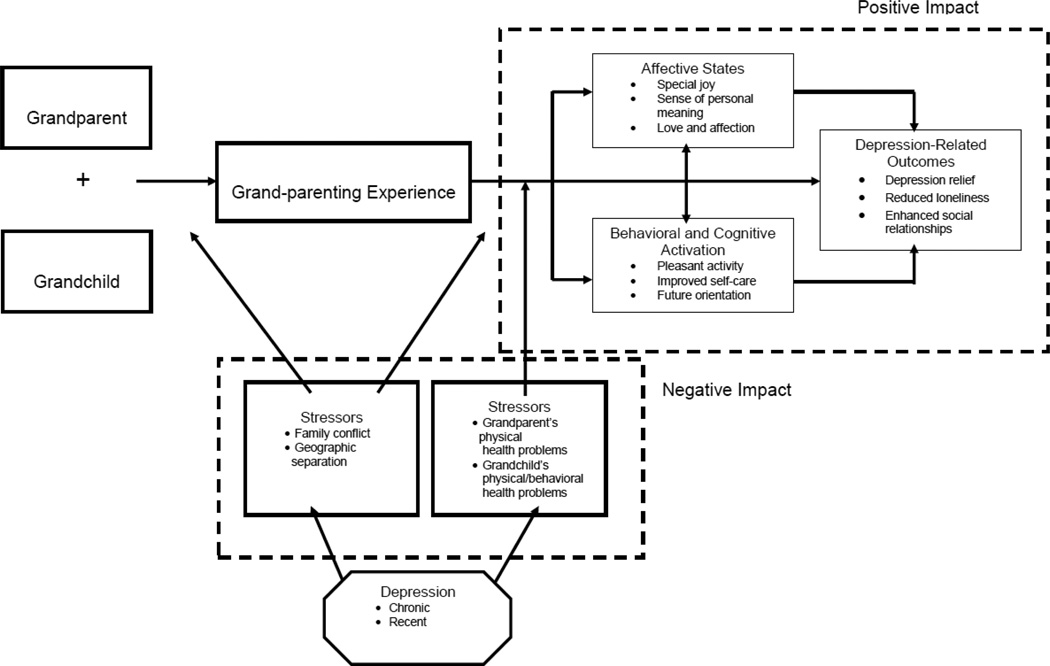

Based on our findings, we propose a potential model of the experience of grand-parenting for adults with a history of depression (Figure). As illustrated, stressors can interfere with the ability to interact with grandchildren or can place a strain on the grand-parenting experience. Chronic and recent depression increases these stressors. Nonetheless, the grand-parenting experience generally affects depression very much like the cognitive behavioral theory of depression [22] posits. Grand-parenting can result in both cognitive and behavioral activation through providing pleasant activities and encouraging positive thinking. This activation improves short-term mood which in turn improves longer term depression outcomes. Positive experiences such as grand-parenting may be important clinical resources as fewer than 50% of depressed adults achieve remission and recover in response to first-line antidepressant pharmacotherapy.[6]

Figure.

Hypothesized impact of grand-parenting experiences among adults with a history of depression

Our study was limited to adults with a history of depression at initial study enrollment who spontaneously mentioned a grand-parenting experience in response to questions about depression, health services use, life stressors, and positive events at long-term follow-up. We did not have an independent measure of whether or not participants had grandchildren, and responses could differ for those not spontaneously mentioning this experience. The data we employed were from qualitative interviewing conducted at long-term follow-up; study participants who were lost to follow-up may have differed from those who participated in the qualitative interviewing. Although the study was well-designed to identify thematic differences between Latina, African American and white women, we did not identify major difference in grand-parenting experiences by racial or ethnic status. We could not explore specific Latino ethnic subgroup differences in grand-parenting experiences. Because women are over-represented among those with depression especially in primary care, our sample comprised fewer men than women; however our sample of 20 men surpasses the number of participants associated with achieving theoretical saturation in qualitative research.[27] An important area for future research will be exploring racial/ethnic differences in grand-parenting experiences among depressed men. Lastly, given our design, we cannot comment on causal connection between grand-parenting experiences and depression, although participants’ comments sometimes suggested specific pathways, such as depression relief being described in association with participants’ reports of grand-parenting experiences.

We also note that, because we employed an existing dataset, we did not have access to some variables influential in the grand-parenting experience, including the timing of becoming a grand-parent,[28, 29] and grandparent and grandchild age and gender.[30, 31] Future studies should examine the relationship between these variables and the experience of grand-parenting among adults with a history of depression.

As the field of older adult depression moves toward an integrative model of mental health risk that incorporates biopsychosocial factors to better understand the onset, maintenance and treatment of mental illness,[6] studies that describe the association between social relationships and depression are increasingly important and relevant. Our work contributes to the field by bringing attention to the highly salient and potentially naturally therapeutic role of grand-parenting in a multi-ethnic sample of adults with a history of depression. Important questions for further investigation are whether grand-parenting may be used to inform therapeutic strategies and bolster psychological resilience among older depressed adults.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Adriana Izquierdo, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, 90024, USA; Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, 90024, USA.

Jeanne Miranda, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, 90024, USA.

Elizabeth Bromley, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, 90024, USA; West Los Angeles VA Healthcare Center, Desert Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), Los Angeles, California, 90073, USA.

Cathy Sherbourne, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, 90407, USA.

Gery Ryan, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, 90407, USA.

David Kennedy, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, 90407, USA.

Kenneth Wells, Center for Health Services and Society, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, 90024, USA.

References

- 1.Charney DS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Lewis L, Lebowitz BD, Sunderland T, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unutzer J. Clinical practice. Late-life depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2269–2276. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp073754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callahan CM, Hui SL, Nienaber NA, Musick BS, Tierney WM. Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:833–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole MG, Bellavance F. The prognosis of depression in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5:4–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Simon G, Grembowski D, Katon W. Quality adjusted life years in older adults with depressive symptoms and chronic medical disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:15–33. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arean PA, Reynolds CF., 3rd The impact of psychosocial factors on late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce ML. Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong SI, Hasche L, Bowland S. Structural relationships between social activities and longitudinal trajectories of depression among older adults. Gerontologist. 2009;49:1–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Wells KB. Personal and psychosocial risk factors for physical and mental health outcomes and course of depression among depressed patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:345–355. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahana E, Kahana B. Theoretical and Research Perspectives on Grandparenthood. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1971;2:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kivnick HQ. Grandparenthood, life review and psychosocial development. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1988;12:63–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverstein M, Marenco A. How Americans Enact the Grandparent Role Across the Family Life Course. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22:493–522. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kivnick HQ. Grandparenthood: an overview of meaning and mental health. Gerontologist. 1982;22:59–66. doi: 10.1093/geront/22.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas JL. Grandparenthood and mental health: implications for the practitioner. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1990;9:464–479. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayslip B, Jr, Kaminski PL. Grandparents raising their grandchildren: a review of the literature and suggestions for practice. Gerontologist. 2005;45:262–269. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E. The health of grandparents raising grandchildren: results of a national study. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1384–1389. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szinovacz ME, DeViney S, Atkinson MP. Effects of surrogate parenting on grandparents' well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54:S376–S388. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.6.s376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unutzer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher LD, Van Belle G. Biostatistics: A Methodology for the Health Sciences. New York: Wiley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewinsohn PM, Libet J. Pleasant events, activity schedules, and depressions. J Abnorm Psychol. 1972;79:291–295. doi: 10.1037/h0033207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luanaigh CO, Lawlor BA. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:1213–1221. doi: 10.1002/gps.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barg FK, Huss-Ashmore R, Wittink MN, Murray GF, Bogner HR, Gallo JJ. A mixed-methods approach to understanding loneliness and depression in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S329–S339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.s329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Ahrens C. Age differences and similarities in the correlates of depressive symptoms. Psychol Aging. 2002;17:116–124. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen GD. Loneliness in later life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8:273–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somary K, Stricker G. Becoming a grandparent: a longitudinal study of expectations and early experiences as a function of sex and lineage. Gerontologist. 1998;38:53–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burton LM, Bengtson VL. Black grandmothers: issues on timing and continuity of roles. In: Burton LM, Bengtson VL, editors. Grandparenthood. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgson LG. Grandparents and older grandchildren. In: Szinovacz ME, editor. Handbook on grandparenthood. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1998. pp. 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas JL. Gender differences in satisfaction with grandparenting. Psychol Aging. 1986;1:215–219. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]