An Nramp-type transporter provides the cytosolic iron that is transferred to bacteroids for synthesis of ferroproteins involved in nitrogen fixation.

Abstract

Iron is critical for symbiotic nitrogen fixation (SNF) as a key component of multiple ferroproteins involved in this biological process. In the model legume Medicago truncatula, iron is delivered by the vasculature to the infection/maturation zone (zone II) of the nodule, where it is released to the apoplast. From there, plasma membrane iron transporters move it into rhizobia-containing cells, where iron is used as the cofactor of multiple plant and rhizobial proteins (e.g. plant leghemoglobin and bacterial nitrogenase). MtNramp1 (Medtr3g088460) is the M. truncatula Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein family member, with the highest expression levels in roots and nodules. Immunolocalization studies indicate that MtNramp1 is mainly targeted to the plasma membrane. A loss-of-function nramp1 mutant exhibited reduced growth compared with the wild type under symbiotic conditions, but not when fertilized with mineral nitrogen. Nitrogenase activity was low in the mutant, whereas exogenous iron and expression of wild-type MtNramp1 in mutant nodules increased nitrogen fixation to normal levels. These data are consistent with a model in which MtNramp1 is the main transporter responsible for apoplastic iron uptake by rhizobia-infected cells in zone II.

SNF is carried out by the endosymbiosis between legumes and diazotrophic bacteria called rhizobia (van Rhijn and Vanderleyden, 1995). Detection of rhizobial nodulation (Nod) factors by the legume plant results in curling of a root hair around the rhizobia and development of an infection thread that will deliver the rhizobia to the developing root nodule primordium, which is also triggered by Nod factors (Kondorosi et al., 1984; Brewin, 1991; Oldroyd, 2013). Rhizobia are eventually released into the cytoplasm of host plant cells via endocytosis, resulting in an organelle-like structure known as the symbiosome, which consists of bacteria surrounded by a plant membrane called the symbiosome membrane (SM; Roth and Stacey, 1989; Vasse et al., 1990). Rhizobia within symbiosomes eventually differentiate into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids that produce and export ammonium to the plant for assimilation (Vasse et al., 1990).

Two main developmental programs for nodulation have been described (Sprent, 2007). In the determinate type, e.g. in soybean (Glycine max), the nodule meristem is active only transiently, which gives rise to a spherical nodule. In the indeterminate nodules, e.g. in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and pea (Pisum sativum), the meristem(s) remain active for much longer, resulting in cylindrical and/or branched nodules of indeterminate morphology. Indeterminate nodules can be divided in spatiotemporal zones that facilitate the study of the nodulation process. At least four zones are observed in a mature indeterminate nodule (Vasse et al., 1990). Zone I is the meristematic region that drives nodule growth. In zone II, rhizobia are released from the infection thread and differentiate into bacteroids. Zone III is the site of nitrogen fixation. Finally, Zone IV is the senescence zone, where bacteroids are degraded and nutrients are recycled. Some authors describe two more zones: the interzone, a transition zone between zones II and III (Vasse et al., 1990; Roux et al., 2014), and zone V, where saprophytic rhizobia live on the nutrients released by senescent cells (Timmers et al., 2000).

Nodulation and nitrogen fixation are tightly regulated processes (for review, see Oldroyd, 2013; Udvardi and Poole, 2013; Downie, 2014) and require a relatively large supply of nutrients from the host: photosynthates, macronutrients such as phosphate and sulfate, amino acids, at least prior to nitrogen fixation, and metal micronutrients (Udvardi and Poole, 2013). Among the latter, iron is one of the most critical (Brear et al., 2013; González-Guerrero et al., 2014). The activity of some of the most abundant and important enzymes in SNF directly depends on iron as cofactor. Nitrogenase, the enzyme directly responsible for nitrogen fixation, needs iron-sulfur clusters and an iron-molybdenum cofactor to reduce N2 (Miller et al., 1993). The hemoprotein leghemoglobin, which controls O2 levels in the nodule (Ott et al., 2005), represents around 20% of total nodule protein (Appleby, 1984). Similarly, different types of superoxide dismutase, including an Fe-superoxide dismutase, control the free radicals produced during SNF (Rubio et al., 2007). Other ferroproteins are involved in energy transduction and recycling related to the nitrogen fixation process (Ruiz-Argüeso et al., 1979; Preisig et al., 1996).

Despite its importance, iron is a growth-limiting nutrient for plants in most soils (Grotz and Guerinot, 2006), especially in alkaline soils. As a result, iron deficiency is prevalent in plants and hampers crop production and human health (Grotz and Guerinot, 2006; Mayer et al., 2008). This is even more so when legumes are nodulated (Terry et al., 1991; Tang et al., 1992). The relatively high iron demand of nodules can trigger the iron deficiency response, i.e. increase in iron reductase activities in the root epidermis and acidification of the surrounding soil (Terry et al., 1991; Andaluz et al., 2009). Consequently, knowing how iron homeostasis is maintained in nodulated legumes, including how this micronutrient is delivered to the nodule, is important for understanding and improving SNF.

Taking advantage of state-of-the-art metal visualization methods, the pathway for iron delivery to the nodule has been elucidated (Rodríguez-Haas et al., 2013). Synchrotron-based x-ray fluorescence studies on Medicago truncatula indeterminate nodules indicate that most of the iron is delivered by the vasculature to the apoplast of zone II. In zone III, iron is mostly localized within bacteroids. Therefore, a number of transporters must exist that move iron through the plasma membrane of plant cells and the SM of infected cells. Several transporters have been hypothesized to mediate iron transport through the SM. Soybean Divalent Metal Transporter1 (GmDMT1) is a nodule-induced Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein (Nramp) that was found in the soybean SM using specific antibodies (Kaiser et al., 2003). However, biochemical studies on Nramp transporters suggest that they transport substrates into the cytosol (Nevo and Nelson, 2006), rather than outwards or into symbiosomes. More recently, the study of stationary endosymbiont nodule1 (sen1) mutants in Lotus japonicus indicated that SEN1, a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Cross Complements CSG1/Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Vacuolar Iron Transporter1 homolog, could play a role in delivering iron across the SM (Hakoyama et al., 2012), albeit this is merely based on the mutant plant phenotype and the role of members of this family in other organisms.

Very little is known about the molecular identity of transporters that mediate iron uptake from the nodule apoplast. Based on known plant metal transporters and their biochemistry, the most likely candidates are members of the Nramp and Zinc-Regulated Transporter1, Iron-Regulated Transporter1-Like Protein (ZIP) families, because these can transport divalent metals into the cytosol (Vert et al., 2002; Nevo and Nelson, 2006). Moreover, given that the expression of at least one Nramp transporter (GmDMT1) is activated by nodulation (Kaiser et al., 2003), it is possible that members of this family might mediate iron uptake into rhizobia-containing cells. Nramp transporters are ubiquitous divalent transition metal importers (Nevo and Nelson, 2006). Phenotypical and electrophysiological studies indicate that they have a wide range of possible biological (Fe2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, and Ni2+) and nonbiological (Pb2+ and Cd2+) substrates (Belouchi et al., 1997; Curie et al., 2000; Thomine et al., 2000; Mizuno et al., 2005; Rosakis and Köster, 2005; Cailliatte et al., 2009). In plants, Nramp transporters have been associated with a number of biological roles, such as Fe2+ and Mn2+ uptake from soil (Curie et al., 2000; Cailliatte et al., 2010), Mn2+ long-distance trafficking (Yamaji et al., 2013), metal remobilization during germination (Lanquar et al., 2005), Cd2+ and Ni2+ tolerance (Mizuno et al., 2005; Cailliatte et al., 2009), and the immune response (Segond et al., 2009), in addition to participating in SNF (Kaiser et al., 2003).

In this study, M. truncatula MtNramp1 (Medtr3g088460) was identified as the Nramp transporter gene expressed at the highest levels in nodules. MtNramp1 protein was localized in the plasma membrane of nodule cells in zone II, where the expression reached its maximum. Its role in iron uptake and its importance for SNF were established using a loss-of-function mutant, nramp1-1. This work adds to our understanding of how apoplastic metals are imported into nodule cells.

RESULTS

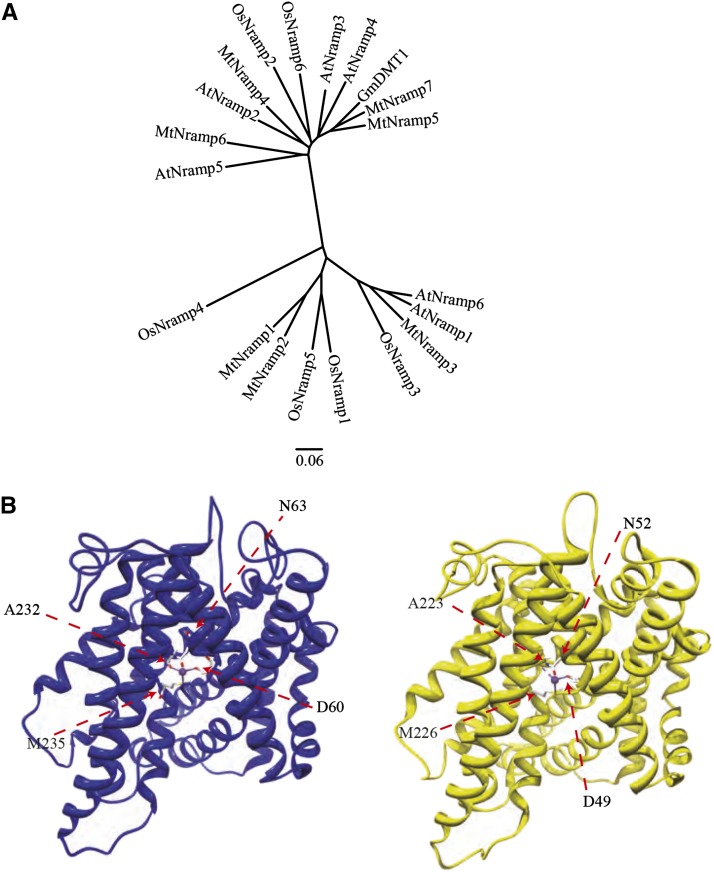

MtNramp1 Transcription Is Induced during Nodule Development

Inspection of the M. truncatula genome sequence revealed eight genes with similarity to Nramp transporters. Seven of them, MtNramp1 to MtNramp7 (Medtr3g088460, Medtr3g088440, Medtr2g104990, Medtr3g102620, Medtr5g016270, Medtr8g028050, and Medtr4g095075, respectively) are similar to Nramp transporters throughout their sequence. The eighth gene (Medtr004150030) is an Arabidopsis Ethylene Insensitive2 homolog that shows a very high sequence similarity to Nramp transporters only in its C terminus. Sequence comparison of the seven MtNramp sequences with known plant Nramp transporters showed that they cluster in two different groups (Fig. 1A). Nodule-specific Nramp transporter GmDMT1 from soybean clusters in the same branch together with MtNramp5 and MtNramp7. MtNramp1 structure was modeled using Staphylococcus capitis DMT structure (Ehrnstorfer et al., 2014; Fig. 1B). The predicted model had a high degree of homology with ScDMT1, sharing the same four metal-coordinating amino acids (D60, N63, A232, and M235 in MtNramp1). The predicted structure also shows the 11 transmembrane domains characteristic of Nramp transporters.

Figure 1.

M. truncatula Nramp family. A, Unrooted tree of the M. truncatula Nramp family transporters MtNramp1 to MtNramp7 (Medtr3g088460, Medtr3g088440, Medtr2g104990, Medtr3g102620, Medtr5g016270, Medtr8g028050, and Medtr4g095075, respectively) and representative plant Nramp homologs AtNramp1 (At1g80830), AtNramp2 (At1g47240), AtNramp3 (At2g23150), AtNramp4 (At5g67330), AtNramp5 (At4g18790), AtNramp6 (At1g15960), OsNramp1 (Os07g0258400), OsNramp2 (Os03g0208500), OsNramp3 (Os06g0676000), OsNramp4 (Os01g0503400), OsNramp5 (Os07g0257200), OsNramp6 (Os12g0581600), and GmDMT1 (Glyma17g18010). B, Tertiary structure modeling of MtNramp1 (blue) and template S. capitis DMT1 (Protein Data Bank Identification: 4WGW, yellow). Positions of metal coordinating amino acids are indicated.

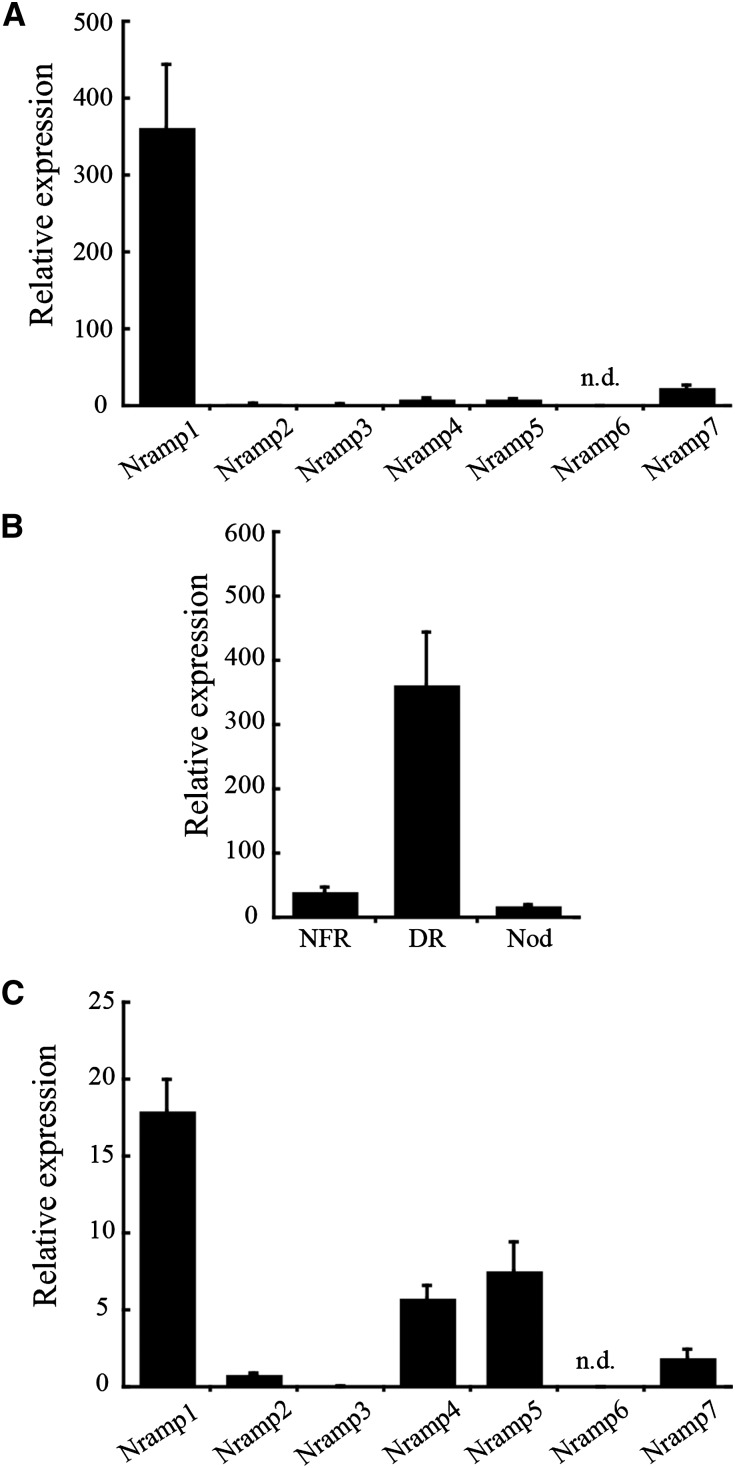

Expression levels of the seven putative transporter genes in 28-d-postinoculation (dpi) nodules, roots fertilized with nitrogen, and denodulated roots (stripped of nodules) were measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. MtNramp1 showed the highest transcript levels in denodulated roots of the seven genes studied (Fig. 2A). None of these genes had significantly higher levels of expression in nodules than in roots (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S1). However, MtNramp1 was the most highly expressed of the seven Nramp-like genes in nodules (Fig. 2C), indicating its preeminent role in these organs.

Figure 2.

MtNramp gene family expression in roots and nodule. A, Gene expression in denodulated roots relative to the internal standard gene Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase. B, MtNramp1 expression in nitrogen-fertilized roots (NFR), denodulated roots (DR), and nodules (Nod) relative to the internal standard gene Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase. C, Gene expression in the nodule relative to the internal standard gene Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase. Data are the mean ± se of three independent experiments. n.d., No transcript was detected.

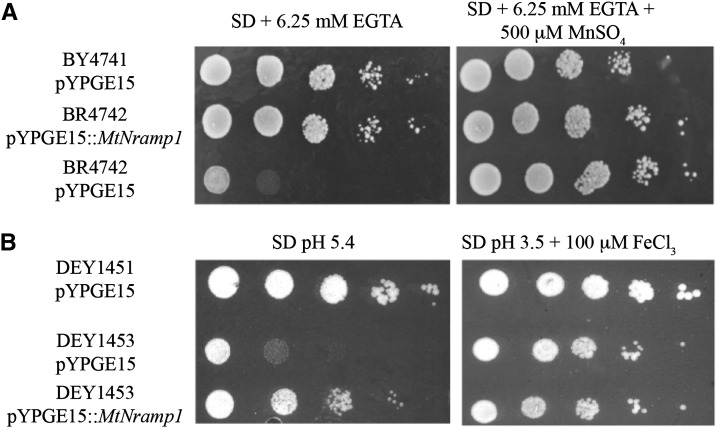

MtNramp1 Is an Iron and Manganese Importer

MtNramp1 substrate and direction of transport were determined by complementation of yeast mutants affected in metal transport. The closest MtNramp1 homolog in yeast is the manganese importer Suppressor of Mitochondria Import Function1 (SMF1; YOL122C). Mutation of SMF1 results in loss of the ability to grow on manganese-depleted medium (Supek et al., 1996; Fig. 3A). To determine whether MtNramp1 is functionally equivalent to SMF1, its complementary DNA (cDNA) was cloned into yeast pYPGE15 vector under the control of the yeast constitutive phosphoglycerate kinase promoter and transformed in the smf1 mutant strain. The transformed strain possessed the ability to grow on low manganese, like the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

MtNramp1 transport assays. A, Manganese import. Yeast strain BY4741 was transformed with the pYPGE15 empty vector, while BY4741-derived BR4742 strain mutated in smf1 was transformed either with empty pYPGE15 or with pYPGE15 containing MtNramp1 coding DNA sequence (CDS). Serial dilutions (10×) of each transformant were grown for 3 d at 30°C on SD Glc medium with all the required amino acids. pH was buffered with 50 mm MES, and manganese levels were kept low with 6.25 mm EGTA. Manganese-replete positive controls were obtained by supplementing the plate with 500 μm MnSO4. B, Iron import. Yeast strain DEY1451 was transformed with the pYPGE15 empty vector, while DEY1451-derived DEY1453 strain mutated in fet3 and fet4 was transformed either with empty pYPGE15 or with pYPGE15 containing MtNramp1 CDS. Serial dilutions (10×) of each transformant were grown for 3 d at 30°C on SD Glc medium with all the required amino acids. Iron-replete positive controls were obtained by growing on pH 3.5 medium supplemented with 100 μm FeCl3.

Nramp transporters have also been implicated in iron import, either from the cell exterior or from an organelle (Curie et al., 2000; Forbes and Gros, 2001). Given the importance of iron in SNF, MtNramp1 iron transport capability was tested by assessing its ability to complement the yeast Fe Transport3 (fe3)/fet4 double mutant. FET3 (YMR058W) is a multicopper ferroxidase involved in high-affinity iron uptake (Askwith et al., 1994), while FET4 (YMR319C) is a low-affinity iron importer (Dix et al., 1994). The double mutant has a severe impairment in iron uptake, requiring higher iron levels in the medium and a more acidic environment to increase this micronutrient mobility and availability. The expression of MtNramp1 in the fet3/fet4 background increased the iron uptake capability of the cells (Fig. 3B). Taken together, the results indicate that MtNramp1 is able to transport iron and manganese toward the cytosol.

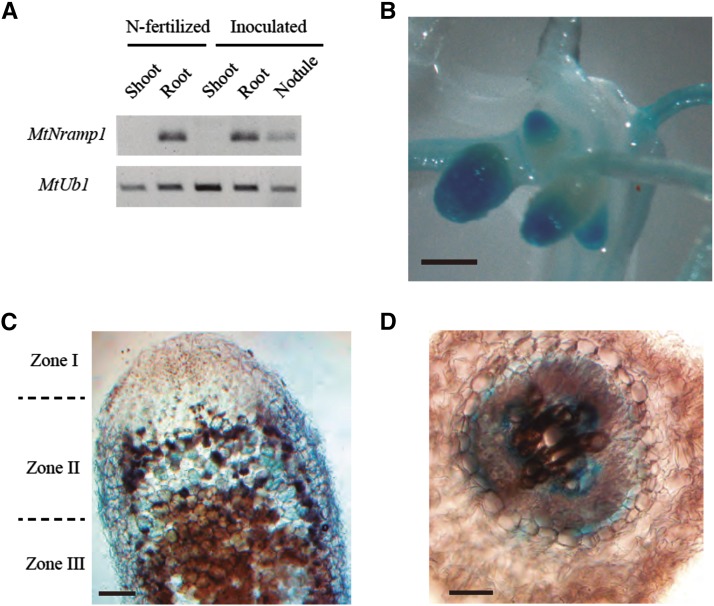

MtNramp1 Is Localized in the Plasma Membrane of Zone II Cells

Nramp transporters are present in a wide range of organs and organelles (Thomine et al., 2000; Oomen et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013). The precise location of the transporters is key to their biological roles, which range from metal uptake from soil (Cailliatte et al., 2010) to metal remobilization from intracellular reserves (Cailliatte et al., 2010; Lanquar et al., 2010). To determine whether MtNramp1 expression is confined to roots and nodules, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR studies were carried out using RNA extracted from shoots, roots, and nodules from nodulated and nonnodulated M. truncatula plants. No MtNramp1 transcript was detected in shoots regardless of symbiotic status (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Organ and tissue location of MtNramp1 transcripts. A, MtNramp1 expression in shoots, roots, and nodules of unnodulated nitrogen-fertilized and nodulated plants. MtUbiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase1 (MtUb1) was used as positive control for RT-PCR. B, Histochemical staining of GUS activity in the root and nodules of M. truncatula plants transformed with plasmid pBI101 containing the MtNramp1-promoter::gus fusion. C, Longitudinal section of a GUS-stained nodule from M. truncatula plants transformed with plasmid pBI101 containing the MtNramp1-promoter::gus fusion. D, Cross section of a GUS-stained root from M. truncatula plants transformed with plasmid pBI101 containing the MtNramp1-promoter::gus fusion. Bars = 1 mm (B) and 0.1 mm (C and D).

To determine the tissue distribution of MtNramp1 expression, M. truncatula seedlings were transformed with Nramp1 promoter::gus fusions, where 2 kb of DNA immediately upstream of the MtNramp1 start codon was selected as promoter. In symbiotic conditions, GUS activity was detected in nodulated roots and in the apical region of the nodule (Fig. 4B). Sections of these nodules showed that GUS expression was mostly confined to zone II (Fig. 4C), while it was detected in a perivascular layer in roots and also in a region that might be associated with the phloem (Fig. 4D).

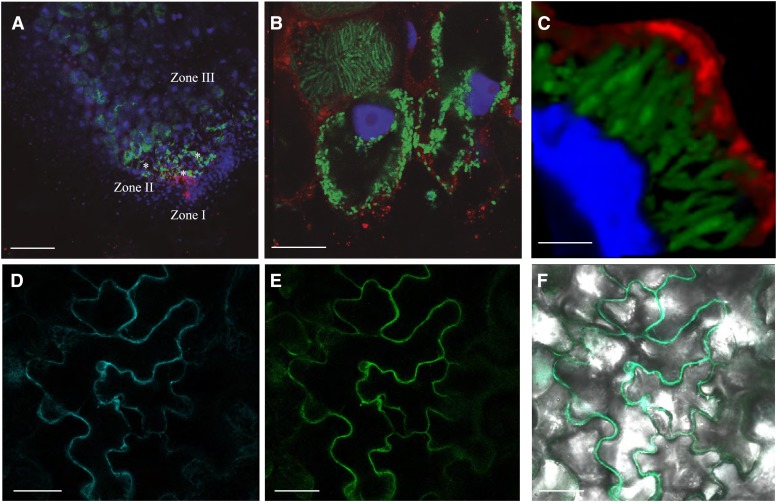

The apical region of the nodule contains both zone I (meristem) and zone II (rhizobia infection and differentiation into bacteroids; Vasse et al., 1990). To verify the GUS-staining results and to determine MtNramp1 subcellular location, immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy were used (Fig. 5). The complete MtNramp1 gene (exons plus introns) was cloned in frame with three hemagglutinin (3xHA) epitopes in its C-terminal end. To avoid misleading results due to overexpression, MtNramp1 was cloned under the control of its own promoter, rather than the constitutive ubiquitin or 35S promoters. The lack of an adverse effect of the 3xHA epitope on protein transport capabilities was verified by complementation of the yeast smf1 mutant with a plasmid constitutively expressing the MtNramp1 coding sequence fused at the C terminus with the 3xHA tag (Supplemental Fig. S2). MtNramp1-HA was detected using a mouse anti-HA antibody and an Alexa594-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (red). Its position within the nodule was mapped with the help of 4′,6-diamino-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain DNA (both eukaryotic and bacterial) and a constitutive GFP-expressing Sinorhizobium meliloti as inoculum (green).

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of MtNramp1-HA. A, Cross section of a 28-dpi M. truncatula nodule infected with S. meliloti constitutively expressing GFP (green) and transformed with a vector expressing the fusion MtNramp1-HA under the regulation of its endogenous promoter. MtNramp1 localization was determined using an Alexa-594-conjugated antibody (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Infection threads are indicated with asterisks. B, Detailed view of rhizobia-infected cells in zone II. C, Three-dimensional reconstruction of a MtNramp1-HA-expressing cell. GFP-expressing S. meliloti cells are shown in green; red indicates the position of MtNramp1-HA, and blue is DAPI-stained DNA. D, Localization of plasma membrane marker pm-CFP transiently expressed in tobacco leaf cells. E, Localization of MtNramp1-GFP transiently expressed in the same cells. F, Overlay of pm-CFP and MtNramp1-GFP localization in tobacco leaf cells. Bars = 100 µm (A), 15 µm (B), 5 µm (C), and 50 µm (D–F).

As expected from the Nramp1 promoter-driven GUS activity, MtNramp-HA was localized to the apical region of the nodule and, more specifically, in the infection/differentiation zone (zone II), as indicated by the presence of GFP-expressing rhizobia and the abundance of infection threads (Fig. 5A). At higher magnification (Fig. 5B), MtNramp1-HA was found in cells where rhizobia were being released and in adjacent cell layers where rhizobia had increased in size following differentiation. MtNramp1-HA was located in the periphery of the cell, very likely in the plasma membrane. No colocalization with mature symbiosomes was observed (Fig. 5C). However, the tagged protein was also detected around the nucleus and in small vesicles in the cytosol, probably the result of protein synthesis and sorting to the plasma membrane. No Alexa594 was detected in control plants transformed with untagged MtNramp1 (Supplemental Fig. S3). To verify the plasma membrane localization, tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves were transformed both with a construct expressing MtNramp1 fused to GFP and plasmid encoding a plasma membrane-targeting motive fused to cyan fluorescent protein (CFP). GFP signal coincided with CFP fluorescent pattern (Fig. 5, D–F), indicating a plasma membrane localization of MtNramp1. Recent studies on gene expression in the different regions of the nodule (Roux et al., 2014) and the public database derived from them (Symbimics) show that MtNramp1 is expressed from zone I to zone III. Expression maxima of MtNramp1 in late zone II and interzone II-III (Supplemental Fig. S4) are consistent with the pattern of distribution observed for MtNramp1-HA in the nodule. MtNramp1-HA was not detected in the vasculature of the nodules analyzed. However, in agreement with the GUS reporter assay, MtNramp1-HA was localized in a cell layer around the vasculature and, at very discrete points, associated with phloem/pericycle (Supplemental Materials and Methods S1; Supplemental Fig. S5, A–C). The perivascular cells corresponded with the endodermis, as Casparian strips were localized in the same layer as MtNramp1-HA (Supplemental Fig. S5, D and E).

Loss of MtNramp1 Function Results in Reduced Nitrogenase Activity

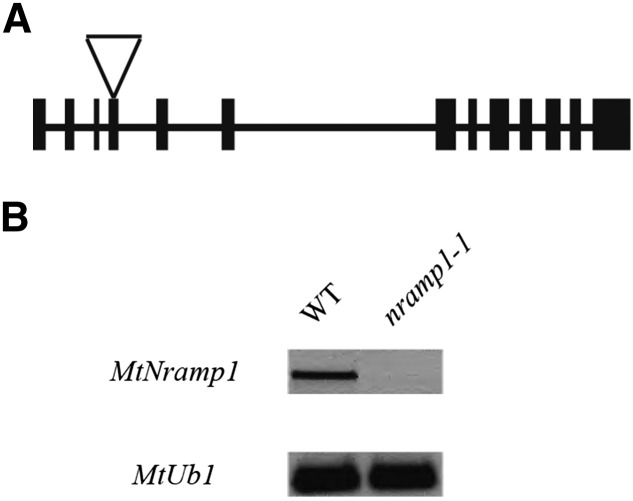

To test the role of MtNramp1 in nitrogen fixation, nramp1 mutants were isolated from a Transposable Element from Nicotiana tabacum1 (Tnt1) insertion mutant collection (Tadege et al., 2008). Mutant line NF20333 had an insertion at position +744 within the fourth exon of the MtNramp1 gene (Fig. 6A), which encodes the central part of the second transmembrane domain according to the structural model (Fig. 1B). Homozygous nramp1-1 mutant plants had no detectable Nramp1 transcript (Fig. 6B), indicating complete loss of function of this gene.

Figure 6.

MtNramp1 Tnt1 insertional knockout line. A, Position of the Tnt1 insertion site for nramp1-1 (NF20333). B, RT-PCR of MtNramp1 expression in 28-dpi nodules in control (wild type [WT]) and nramp1-1 M. truncatula lines. Expression of MtUbiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (MtUb1) was used as positive control.

Given that MtNramp1 was expressed in both nodulated and nonnodulated plants, the phenotype of the nramp1-1 mutant was assessed under both conditions. Under nonsymbiotic conditions, nramp1-1 mutants exhibited normal wild-type-like growth, fresh weight, and chlorophyll content regardless of iron levels in the nutrient solution (Supplemental Fig. S6). However, root iron content was significantly higher in the roots of nramp1-1 than in the wild type when plants were grown with no additional iron in the nutrient solution (Supplemental Fig. S6D). The reverse was true for shoots, with iron levels lower in the mutant than in the wild type under these growth conditions (Supplemental Fig. S6D). Iron nutrition status was monitored using M. truncatula Ferric Reduction Oxidase1 (MtFRO1; Medtr8g028780) expression, a marker of M. truncatula iron deficiency response (Andaluz et al., 2009). Regardless of the iron levels in the nutritive solution, no significant differences were observed between MtFRO1 expression in wild-type and nramp1-1 lines (Supplemental Fig. S6E).

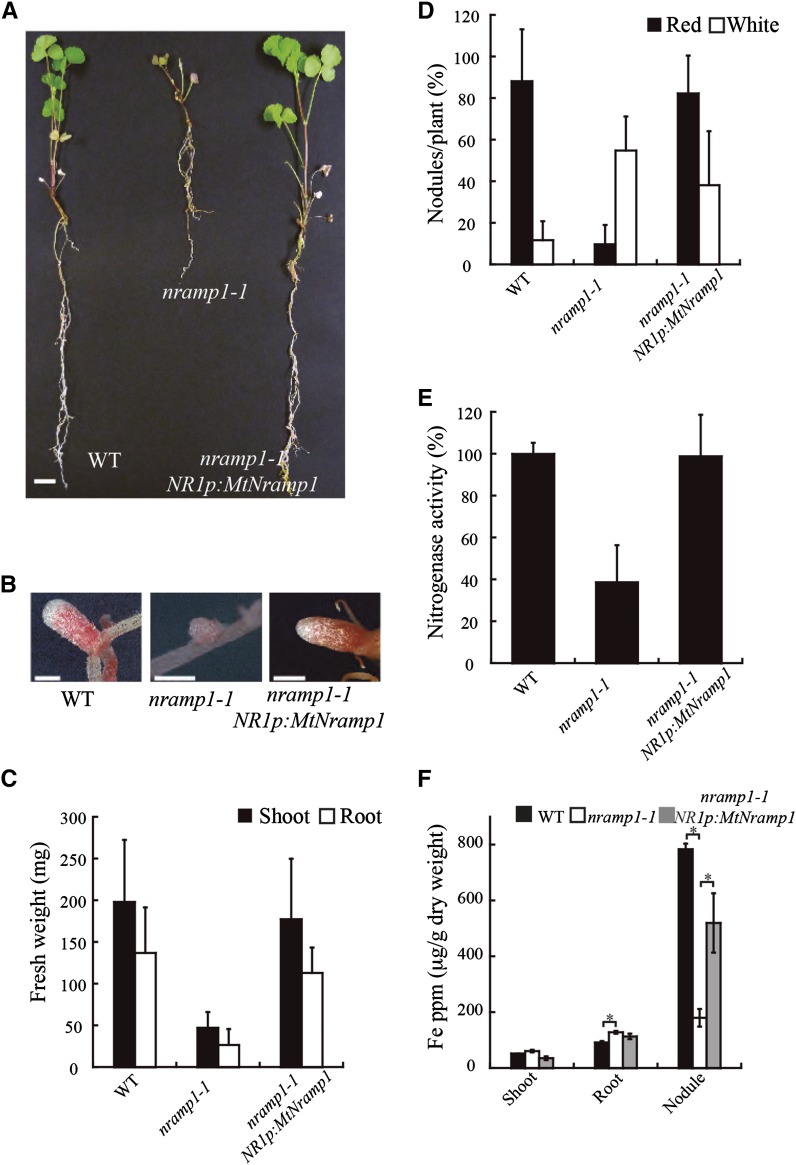

Under symbiotic conditions, without extra added nitrogen fertilizer, nramp1-1 plants had severe growth defects (Fig. 7A). Mutant plants had mostly small white nodules, in contrast to the mostly larger, pink nodules of wild-type plants (Fig. 7B). Plant biomass was reduced by 79% in the mutant compared with the wild type (Fig. 7C). Nodulation was also impaired in the mutant, with 36% fewer nodules than the wild type (Fig. 7D). Nitrogenase activity of nodulated plants was measured using the acetylene reduction assay (Dilworth, 1966; Schöllhorn and Burris, 1966). Mutant plants grown under standard conditions showed a 40% reduction in nitrogenase activity compared with control transformed plants (Fig. 7E). These aberrant phenotypes of the nramp1-1 mutant were not the result of insertions in other genes, as wild-type phenotypes were restored to nramp1-1 roots transformed with wild-type MtNramp1-HA driven by its native promoter (the same construction used for the immunolocalization studies; Fig. 7, A–F). Furthermore, the phenotypes were associated with a reduction of iron uptake by the mutant, as wild-type phenotypes were restored when mutant plants were watered with an iron-fortified solution (Supplemental Fig. S7). nramp1-1 had significantly higher iron levels in nodulated roots than in wild-type plants, while the reverse was true for nodules (Fig. 7F). Perl-DAB staining of wild-type and nramp1-1 nodules showed neither changes in iron distribution nor the absence of major iron hotspots due to the mutation in MtNramp1 (Supplemental Fig. S8, A and B). This result suggests that the difference in nodular iron content is merely due to the smaller nodule zone III developed by nramp1-1 plants (less iron available means fewer ferroproteins and, therefore, a smaller nitrogen fixation zone). However, nodulated roots in nramp1-1 showed some discrete iron hotspots in the apoplast not present in wild-type roots (Supplemental Fig. S8, C–E), corresponding to the increased iron concentration. No significant differences in iron content of shoots were found between mutant and wild-type plants under symbiotic conditions (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7.

Symbiotic phenotype of M. truncatula wild type (WT), nramp1-1, and nramp1-1 transformed with MtNramp1 regulated under its endogenous promoter (NR1p). A, Growth of representative plants. Bar = 1 cm. B, Close view of representative nodules of each M. truncatula line. Bar = 1 mm. C, Fresh weight of shoots and roots. Data are the mean ± se (n = 6–8 plants). D, Nodule number per plant; 100% = 5.67 nodules/plant. Data are the average ± se (n = 7 plants). E, Nitrogenase activity in 28-dpi nodules. Acetylene reduction was measured in duplicate from two sets of five pooled plants. Data are the mean ± se; 100% = 42.83 nmol ethylene h–1 g–1. F, Iron content (μg g−1) in 28-dpi plants. Bars indicate the average ± se of two sets of five transformed plants. Asterisk indicates significant differences (P ≤ 0.05).

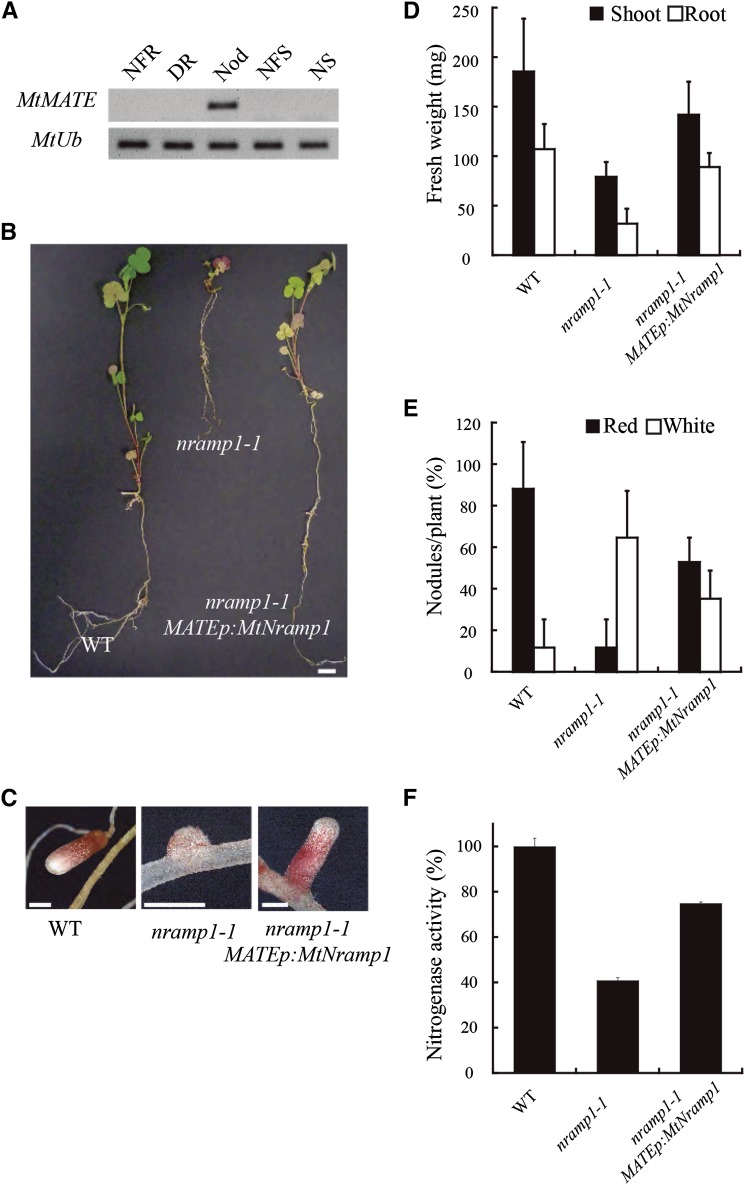

To determine whether reduced iron accumulation in mutant nodules resulted from loss of Nramp1 function in nodules, as opposed to roots, nramp1-1 plants were transformed with MtNramp1 driven by the nodule-specific promoter of the Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion (MATE) gene, Medtr6g081400, which is also predominantly expressed in zone II (Fig. 8A; Supplemental Fig. S4). Targeted expression of MtNramp1 to nodules of the nramp1-1 mutant restored the normal growth to symbiotic nramp1-1 plants (Fig. 8B). These plants also had active pink nodules instead of the small white nodules shown by nramp1-1 plants (Fig. 8C), as well as an increase in the biomass (Fig. 8D) and in the total number of nodules (Fig. 8E) and an 85% increase in nitrogenase activity compared with the nramp1-1 control (Fig. 8F).

Figure 8.

Complementation of nramp1-1 phenotype by MtNramp1 under the regulation of a nodule-specific promoter. A, Expression of Medtr6g081400, a nodule-specific MATE transporter used as a promoter source for the complementation construct. Expression of MtUbiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase was used as positive control (MtUb). B, Growth of representative plants. C, Close view of representative nodules of each M. truncatula line. D, Fresh weight of shoots and roots. Data are the mean ± se (n = 4 plants). E, Nodule number per plant; 100% = 4.25 nodules/plant. Data are the average ± se (n = 4 plants). F, Nitrogenase activity in 28-dpi nodules. Acetylene reduction was measured in duplicate from two sets of five pooled plants. Data are the mean ± se; 100% = 31.85 nmol ethylene h–1 g–1. NFR, Nitrogen-fertilized roots; DR, denodulated roots; Nod, nodules; NFS, nitrogen-fertilized shoots; NS, shoots from nodulated plants; WT, wild type. Bars = 1 cm (B) and 1 mm (C).

Yeast complementation assays indicated that MtNramp1 was also a Mn2+ importer. To test whether MtNramp1 mutation had an effect on M. truncatula manganese homeostasis, nramp1-1 symbiotic and nonsymbiotic phenotypes were assessed in plants watered either with the standard manganese concentrations or with a nutritive solution in which no manganese was added. No significant changes in the phenotype were observed in nonsymbiotic (Supplemental Fig. S9) or symbiotic conditions (Supplemental Fig. S10), other than a reduction in manganese content in nramp1-1 roots under manganese-deficient conditions and an increase in nramp1-1 shoots when watered with manganese-replete nutritive solution (Supplemental Figs. S9D and S10F).

DISCUSSION

Legumes are key to world agriculture (Graham and Vance, 2003). They are the main protein source in many areas of the world and, because of SNF, a viable alternative to the use of nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture (Smil, 1999). As in any plant, iron uptake and systemic distribution is critical in legumes. Like in other nongraminaceous plants, in legumes, iron uptake from soil follows what is known as Strategy I, i.e. Fe3+ solubility is increased by acidification of the surrounding soil and then Fe3+ is reduced by a ferroreductase to Fe2+, which is imported into plants via specific transporters in the root epidermis (Andaluz et al., 2009). Once inside the plant, iron is used in legumes as in other plants, with one exception; in addition to the shoot, there is an extra iron sink during vegetative stages of growth, namely the root nodule (Tang et al., 1990).

Nodulation requires relatively large amounts of iron to synthesize the key enzymes involved in SNF (Brear et al., 2013; González-Guerrero et al., 2014). Synchrotron-based x-ray fluorescence results indicate that, at least in indeterminate nodules, iron is primarily delivered by the vasculature and released into the apoplast of zone II (Rodríguez-Haas et al., 2013). In this zone and probably in the interzone with the nitrogen-fixing zone III, iron has to be delivered from apoplast into cells before it is transported to the bacteria in symbiosomes. Our results indicate that MtNramp1 participates in iron translocation across the plasma membrane.

In contrast to soybean (Kaiser et al., 2003), M. truncatula does not encode a nodule-specific Nramp transporter. However, among the seven identified members of the M. truncatula Nramp family, MtNramp1 showed by far the highest expression level in nodules. Yeast complementation assays indicated that MtNramp1 can transport iron and manganese into cells, consistent with a putative role in iron uptake by nodule cells infected with rhizobia. However, for this to be the case in M. truncatula, MtNramp1 should be localized in the plasma membrane in zone II cells.

Because iron is released into the apoplast of zone II cells, and because little or no iron remains in the zone III apoplast (Rodríguez-Haas et al., 2013), the conclusion is that Nramp or ZIP transporter(s) must mediate iron uptake from the apoplast into the cytosol of cells in this region of the nodule. Promoter::gus fusion data and the gene expression information from the Symbimics database for MtNramp1 indicated that the gene is expressed in zone II of the nodule. Furthermore, immunolocalization studies of the transporter and its colocalization with plasma membrane markers indicated that it is located in the plasma membrane, in contrast to GmDMT1, which was found on the SM (Kaiser et al., 2003). This localization in M. truncatula does not appear to be an artifact of any of the fusions created, because (1) the addition of the HA tag did not have any major effect on the structure of the protein, as evidenced by the conservation of its transport capabilities in yeast and in M. truncatula, and (2) transcriptomic data on MtNramp1 expression on different parts of the nodule (Roux et al., 2014) showed maximum expression in zone II and the interzone II-III, precisely where iron is most prevalent in the apoplast. These data may also explain why average MtNramp1 transcript levels in whole nodules are lower than in roots; because MtNramp1 is confined to just a few cell layers, its mRNA is diluted by the mRNA from the many other nodule cells that do not express this gene.

Further evidence for a role of MtNramp1 in iron delivery for SNF is provided by the analysis of nramp1-1 mutant plants. These plants accumulated higher levels of iron in roots than wild-type plants under low-iron growth conditions. This is consistent with the localization of MtNramp1 in the root endodermis (the cell layer in which the Casparian strip was visualized). Mutation of a transporter involved in iron translocation into endodermal cells would result in iron accumulation in the root apoplast, and as a result, root iron content would be increased. This was observed in nramp1-1 roots, where some iron deposits were detected in the apoplast. However, the role of MtNramp1 in nonsymbiotic conditions seems to be very limited, even under low-iron conditions, given that no additional phenotype was observed and that the iron deficiency response was not further induced in the mutant. Alternatively, other endodermal transporters might be masking a nonsymbiotic nramp1-1 phenotype. Regardless of the mechanism, the fact that the nramp1-1 mutant had neither significant difference in chlorophyll content compared with wild-type plants nor triggered the iron deficiency response indicates that sufficient iron was reaching the sink organs regardless of MtNramp1 activity. These results suggest that (1) MtNramp1 might be involved in the uptake of iron delivered to the endodermis through the apoplastic pathway, and (2) the iron that reaches the endodermis through the symplastic pathway is sufficient to fulfill the plant iron requirements in nonsymbiotic conditions.

In stark contrast to nonsymbiotic plants, nramp1-1 plants grown under symbiotic conditions, without substantial mineral nitrogen, had severe growth defects, with a dramatic reduction of biomass. This was accompanied by a reduction of nodulation and nitrogenase activity in these plants. All these phenotypes were suppressed by adding high levels of iron-Sequestrene chelate to the nutrient solution or by expressing the wild-type MtNramp1 in the mutant plants, indicating the importance of MtNramp1 in iron delivery for SNF. However, it might be argued that this defect was due to iron not being introduced in the vasculature and, consequently, not being transported to the nodule, in view of the reduced iron content in nramp1-1 nodules (Fig. 7F). To test this hypothesis, MtNramp1 was fused to a promoter from a nodule-specific MATE gene with a similar expression pattern to MtNramp1 in nodules. This chimera was able to improve the growth of nramp1-1 as well as increase the number of functional nodules, as indicated by the more abundant red nodules and their increased nitrogenase activity. Therefore, although some of the nramp1-1 phenotype is due to iron being retained in the root, a substantial part is likely due to an inability of nodule cells to take up iron from the apoplast.

While playing a role in iron homeostasis, MtNramp1 does not seem to have any significant role on manganese nutrition, despite its ability to transport Mn2+ shown in yeast (possibly an acquired ability that could result from overexpressing the transporter in a heterologous system). The observed reduction of manganese content in nramp1-1 roots under some conditions indicated that MtNramp1 is not involved in manganese transport in planta. The changes in manganese levels by MtNramp1 mutation could be the result of the plant adapting to an altered long-distance iron transport, a consequence to the changes in iron distribution caused by MtNramp1 mutation.

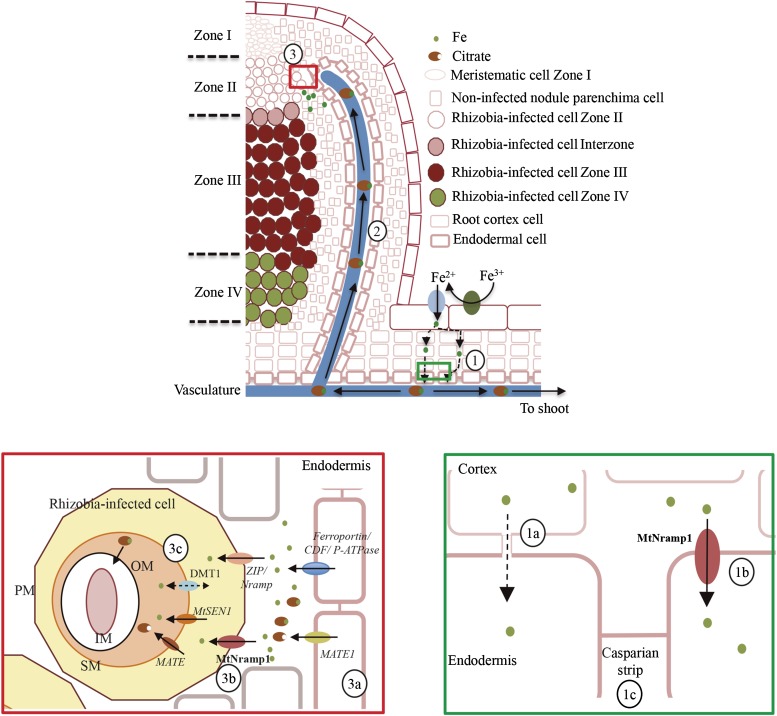

In conclusion, MtNramp1 appears to play a major role in iron uptake from the apoplast into rhizobia-containing cells in zone II of the nodule and a minor role in root-to-shoot iron translocation. This is in contrast to another Nramp transporter, GmDMT1 of soybean, which has been localized in the symbiosome (Kaiser et al., 2003). Other transporters might assist MtNramp1 in transporting iron in nodules, as the nramp1-1 mutant produced some partially functional nodules. MtNramp7 could potentially play this role, because it is the only other M. truncatula Nramp family member with a pattern of expression similar to that of MtNramp1. However, MtNramp7 exhibited low expression levels in the nodule, and according to the database Symbimics, it is expressed mostly in zone III instead of zone II. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that a ZIP or even a Yellow Stripe-Like (YSL) transporter may contribute to iron uptake into nitrogen-fixing cells. Taking into account these considerations, a tentative model of iron transport to indeterminate nodules is presented in Figure 9. In this model, iron is incorporated from soil using Strategy I and guided to the vasculature via symplastic and apoplastic routes. To reach the vessels, apoplastic iron has to be taken up by endodermal cells, very likely with the assistance of MtNramp1. Iron is released from the vasculature in zone II of the nodule by a yet-to-be-identified transporter. Citrate may play a role in this release, because mutation of the MATE transporter LjMATE1 in L. japonicus results in iron accumulation in the nodule vasculature (Takanashi et al., 2013). Although this observation was made in determinate-type nodules, iron released from the vasculature is likely to follow a similar mechanism in indeterminate nodules. Iron accumulates in the apoplast, where MtNramp1 and perhaps other transporters move it into the cytosol. From there, a putative homolog of LjSEN1 may be responsible for iron translocation across the SM (Hakoyama et al., 2012). In this process, an additional citrate transporter might play a role, given that iron-citrate is the preferred source of chelated iron for some rhizobia (LeVier et al., 1996). Future studies will be directed toward testing this model as well as toward determining the identity of transporters responsible for iron release from the vasculature.

Figure 9.

Proposed model of iron delivery to rhizobia-containing cells. Iron is incorporated from soil using Strategy 1 and delivered symplastically and apoplastically to the endodermal layer (1). Symplastic iron reaches the cytosol of endodermal cells (1a), while apoplastic iron is incorporated by these cells with the help of MtNramp1 (1b). This element is then transferred to the xylem (1c) to be transported to the rest of the plant as an iron-citrate complex (2). Iron is delivered to zone II of the nodule (3) and released from the vasculature in a process in which citrate efflux is likely to be necessary. A MATE family member homologous to LjMATE1 might facilitate citrate efflux (3a). MtNramp1 translocates iron across the plasma membrane (3b). In this role, an additional metal transporter (ZIP or YSL) could also be involved. Once in the cytosol, iron is likely to be transported across the SM by MtSEN1 in a process that might be assisted by another MATE family transporter (3c). An M. truncatula GmDMT1 ortholog could also participate in iron transport either by introducing iron or rather by effluxing iron to prevent overload of the peribacteroidal space. Putative transporters predicted to play a role in metal transport in the nodule are indicated in italics. PM, Plasma membrane; SM, symbiosome membrane; IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane; CDF, cation diffusion facilitator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological Materials and Growth Conditions

Medicago truncatula R108 seeds were scarified by incubating for 7 min with concentrated H2SO4. Washed, scarified seeds were surface sterilized with 50% (v/v) bleach for 90 s and left overnight in sterile water. After 48 h at 4°C, seeds were germinated in water-agar plates at 22°C for 48 h. Seedlings were transferred to sterilized perlite pots and inoculated with Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 or S. meliloti 2011 transformed with pHC60 (Cheng and Walker, 1998), as indicated. Plants were grown in a greenhouse with 16 h of light and 22°C and watered every 2 d with Jenner’s solution or water, alternatively (Brito et al., 1994). When indicated, water was supplemented with 0.5 g L–1 Sequestrene (Syngenta). Nodules were collected 28 dpi. Nonnodulated plants were similarly grown, but instead of being inoculated with S. meliloti, they were watered every 2 weeks with solutions supplemented with 2 mm NH4NO3. For hairy-root transformations, M. truncatula seedlings were transformed with Agrobacterium rhizogenes ARqua1 carrying the appropriate binary vector as described (Boisson-Dernier et al., 2001). Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) agroinfiltration experiments were carried out by transforming leaves with the plasmid constructs in Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (Deblaere et al., 1985). Tobacco plants were grown in the greenhouse under the same conditions as M. truncatula.

For heterologous expression, the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) strains DEY1453 (ade2/+ canl/canl his3/his3 leu2/leu2 trpl/trpl ura3/ura3 fet3-2::HIS3/fet3-2::HIS3 fet4-1::LEU2/fet4-1::LEU2), DEY1451 (MATa/MATa ade2/+ canl/canl his3/his3 leu2/leu2 trpl/trpl ura3/ura3; Dix et al., 1994), BY4741 (his3 leu2 met1 ura3), and BR4742 (his3 leu2 met1 ura3 Δsmf1; Thermo Scientific) were used. DEY1453 needs 100 μm iron supplementation and pH 3.5 to grow (Dix et al., 1994), and BY1457 cannot grow when 6.25 mm manganese-chelating EGTA is added to the medium unless supplemented with manganese (Portnoy et al., 2000). All strains were grown in synthetic dextrose (SD) or yeast peptone dextrose (Sherman et al., 1986) medium supplemented with necessary auxotrophic requirements with 2% (w/v) Glc as the carbon source.

RNA Extraction and qPCR

RNA was obtained using Tri-Reagent (Life Technologies), DNase treated and cleaned with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Putative DNA contamination was checked by PCR on RNA extraction using M. truncatula Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (Medtr4g077320.1) primers (Table I). RNA quality was verified on a denaturing agarose gel. cDNA was obtained from 1 μg of DNA-free RNA using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen).

Table I. Primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequence | Use |

|---|---|---|

| 5MtNramp1-XbaI | AATCTAGAATGGCACATCAAGAAGTGAAT | Cloning of MtNramp1 cDNA in pYGPE15 |

| 3MtNramp1-BamHI | TTGGATCCTCACAACCTAGGTCCCTCTG | Cloning of MtNramp1 cDNA in pYGPE15 |

| 5MtNramp1p-HindIII | GGAAGCTTTTTTTATTTGAACTTAGAATTA | Cloning of MtNramp1 promoter in pBI101 |

| 3MtNramp1p-BamHI | TTGGATCCGTTTACTATTACTATTCACTC | Cloning of MtNramp1 promoter in pBI101 |

| 5GWMtNramp1p | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTATTGAACTTAGAATTAAACCAC | Cloning of MtNramp1 promoter and coding sequence in Gateway vectors |

| 3GWMtNramp1 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTACAACCTAGGTCCCTCTGGTCG | Cloning of MtNramp1 promoter and coding sequence in Gateway vectors/C-terminal GFP fusion |

| 5MtUBqF | GAACTTGTTGCATGGGTCTTGA | Quantitative reverse transcription (q)PCR of MtUbiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase |

| 3MtUBqR | CATTAAGTTTGACAAAGAGAAAGAGACAGA | qPCR of MtUbiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase |

| 5MtNramp1 + 1GW | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCATGGCACATCAAGAAGTGAAT | C-terminal GFP fusion of MtNramp1 |

| 5MtNRAMP1-1533 | AAGGGGTTTGTAAACGATGGTCAGT | qPCR of MtNramp1 |

| 3MtNRAMP1-1659 | GCTCTCTAAAATGACTTGAAAGCAA | qPCR of MtNramp1 |

| 5MtNRAMP2-1500 | AACCAAGTGGAAAAAGGAATTGTGG | qPCR of MtNramp2 |

| 3MtNRAMP2-1617 | TTGGATCCTTTATTCTGGTAGTGGT | qPCR of MtNramp2 |

| 5MtNRAMP3-1431 | TTTTCAGGCATGGCAGTATATTTGG | qPCR of MtNramp3 |

| 3MtNRAMP3-1598 | TGGACTACTTCTCTGAGGCAATTGC | qPCR of MtNramp3 |

| 5MtNRAMP4-1427 | CTTCCTTTCTGAGGTGAACAGCGTA | qPCR of MtNramp4 |

| 3MtNRAMP4-1586 | TCCATATTTTTAATGTTGTGTAACTTGTGT | qPCR of MtNramp4 |

| 5MtNRAMP5-1387 | TTTCCTCTGAAGTGAGTGGAGCAGT | qPCR of MtNramp5 |

| 3MtNRAMP5-1565 | AACTTTGCGTGGTAGCTACTATTTG | qPCR of MtNramp5 |

| 5MtNRAMP6-1527 | TGTGCAACAGCATGGATTTCATTTA | qPCR of MtNramp6 |

| 3MtNRAMP6-1663 | CTATATATTCACATCATCATCACCAAAAA | qPCR of MtNramp6 |

| 5MtNRAMP7-1423 | AATAACCGCTGCATATGTTGCATTC | qPCR of MtNramp7 |

| 3MtNRAMP7-1549 | CTGCAGTTCTAAGGATCCATTATTCA | qPCR of MtNramp7 |

| 5MtFRO1qF | GGTGACACGTGGATCATCTG | qPCR of MtFRO1 |

| 3MtFRO1qR | TTGCAATCCACAGGAACAAA | qPCR of MtFRO1 |

Gene expression was studied by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (9700, Applied Biosystems) with primers indicated in Table I and standardized to the M. truncatula Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase gene. Real-time cycler conditions have been previously described (González-Guerrero et al., 2010). Determinations were carried out with RNA extracted from three independent biological samples, with the threshold cycle determined in triplicate. The relative levels of transcription were calculated using the 2−ΔCt method. In all RT-PCR reactions, a non-RT control was used to detect any possible DNA contamination.

Yeast Complementation Assays

MtNramp1 cDNA was cloned between the XbaI and BamHI sites of yeast expression vector pYPGE15. Restriction sites were added to MtNramp1 CDS by PCR-using primers 5MtNramp1-XbaI and 3MtNramp1-BamHI (Table I). Yeast transformations were performed using a lithium acetate-based method (Schiestl and Gietz, 1989). Cells transformed with pYPGE15 or pYPGE15::MtNramp1 were selected in SD medium by uracil autotrophy. For phenotypic tests, DEY1453 and DEY1451 were plated in SD, pH 3.5, supplemented with 100 μm FeCl3, and in SD, pH 5.4. BY4741 and BR4742 transformants were plated in SD plates supplemented with 50 mm MES, pH 6.0, and 6.25 mm EGTA, with or without 500 μm MnSO4.

GUS Staining

pMtNramp1::gus was constructed by amplifying 2 kb upstream of the MtNramp1 start codon using primers 5MtNramp1p-HindIII and 3MtNramp1p-BamHI (Table I). The digested product was ligated into the BamHI/HindIII sites in pBI101 (Jefferson et al., 1987). Hairy-root transformation was performed as described above. GUS activity was measured in roots of 28-dpi plants as described (Vernoud et al., 1999).

Confocal Microscopy Detection of MtNramp1-HA

A DNA fragment containing the full-length MtNramp1 genomic region and the 2 kb upstream of its start codon was cloned in pGWB13 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) using Gateway Technology (Invitrogen). This vector adds three C-terminal HA tags in frame. Hairy-root transformation was performed as described above. Transformed plants were inoculated with S. meliloti 2011 containing the pHC60 plasmid that constitutively expresses GFP. Nodules from 28-dpi plants were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 2.5% (w/v) Suc in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C overnight. Nodules were then washed in PBS, and 100-μm sections were obtained with a Vibratome 1000 Plus. Sections were then dehydrated in a methanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% [v/v] in PBS) for 5 min and then rehydrated. Cell walls were permeabilized with 2% (w/v) cellulose in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and treated with 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 for 15 min. Sections were blocked with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in PBS and incubated with an anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody (Sigma) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing the primary antibody, an Alexa594-conjugated anti-mouse rabbit monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was added to the sections for 1 h at room temperature. After washing away the unbound antibody, DNA was stained with DAPI. Images were acquired with a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica SP8).

Transient MtNramp1 Expression by Agroinfiltration in Tobacco Leaves

Experiments were performed as described by Voinnet et al. (2003). MtNramp1 CDS was fused to GFP at the C terminus by cloning in pGWB5 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) using Gateway Technology (Invitrogen). These constructs and the plasma membrane marker pm-CFP pBIN (Nelson et al., 2007) were introduced into A. tumefaciens C58C1 (Deblaere et al., 1985) by electroporation. Transformed cells were selected on Luria-Bertani plates supplemented with Rifampicin (50 μg mL–1) and Kanamycin (50 μg mL–1). The transformants were grown in liquid Luria-Bertani medium to late exponential phase. Cells were then centrifuged and resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm of 1 in 10 mm MES, pH 5.6, containing 10 mm MgCl2 and 150 μm acetosyringone. These cells were mixed with an equal volume of A. tumefaciens C58C1 expressing the silencing suppressor p19 of Tomato bushy stunt virus (pCH32 35S:p19; Voinnet et al., 2003). Bacterial suspensions were incubated for 3 h at room temperature and then injected into young leaves of 4-week-old tobacco plants. Leaves were examined after 3 d by confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

Isolation of a Tnt1 Mutant for MtNramp1

Insertional mutant for MtNramp1 was identified in the course of reverse genetic screening performed on retrotransposon Tnt1 mutant population (Tadege et al., 2008). The procedure was based on nested PCR as described previously (Cheng et al., 2011).

Acetylene Reduction Assay

Nitrogenase activity was measured by the acetylene reduction assay (Hardy et al., 1968). Nitrogen fixation was assayed in mutant and control plants 28 dpi in 25-mL tubes fitted with rubber stoppers. Each tube contained five independently transformed plants. Two and one-half milliliters of air inside was replaced with 2.5 mL of acetylene. Tubes were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Gas samples (0.5 mL) were analyzed in a Shimadzu GC-8A gas chromatograph fitted with a Porapak N column. The amount of ethylene produced was determined by measuring the height of the ethylene peak relative to background. Each point consists of two tubes, each with five pooled plants. After measurements, nodules were recovered from roots to measure their weight.

Metal Content Determination

Total reflection x-ray fluorescence analysis was used to determine iron content in 28-dpi mutant nodules isolated and pooled from 10 different plants. Analyses were carried out at Total Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Laboratory (Interdepartmental Research Service, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid). Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry was carried out at the Unit of Metal Analysis (Scientific and Technology Centres, Universidad de Barcelona).

Bioinformatics

To identify M. truncatula Nramp family members, BLASTN and BLASTX searches were carried out in the M. truncatula Genome Project site (http://www.jcvi.org/medicago/index.php). Sequences from model Nramp genes were obtained from the Transporter Classification Database (http://www.tcdb.org/; Saier et al., 2014). Protein sequence comparison and unrooted tree visualization were carried out using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) and FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Structural modeling was done using SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/; Guex et al., 2009).

Statistical Tests

Data were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test to calculate statistical significance of observed differences. Test results with P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. MtNramp gene family expression.

Supplemental Figure S2. MtNramp1-HA yeast complementation assay.

Supplemental Figure S3. Antibody-specific control for immunolocalization.

Supplemental Figure S4. Expression in the different M. truncatula nodule zones.

Supplemental Figure S5. MtNramp1-HA localization in the root.

Supplemental Figure S6. Phenotype of nramp1-1 under nonsymbiotic conditions.

Supplemental Figure S7. Iron complementation of the nramp1-1 phenotype.

Supplemental Figure S8. Iron distribution in roots and nodules of wild-type and nramp1-1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S9. Nonsymbiotic phenotype of nramp1-1 under Mn deficiency conditions.

Supplemental Figure S10. Symbiotic phenotype of nramp1-1 under two different Mn concentrations.

Supplemental Materials and Methods S1. Perl-DAB and Casparian strip staining methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alonso Rodríguez-Navarro (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid) for providing plasmid pYPGE15, Dr. David Eide (University of Wisconsin, Madison) for the strain fet3/fet4 and its parental strain, Dr. Benoit Lefebvre (Laboratoire des Interactions Plantes Microorganismes) for the pBI101 vector, Dr. Florian Frugier (Institut des Sciences du Vegétal) for the pFRN vector, Dr. Rosario Haro (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid) for the organelle-specific markers, Dr. Regla Bustos (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agroalimentarias) for the agroinfiltration protocol, Dr. Larry Peterson for the Casparian strip visualization method, and Dr. Tsuyoshi Nakagawa (Shiimane University) for the pGWB vectors.

Glossary

- SNF

symbiotic nitrogen fixation

- SM

symbiosome membrane

- dpi

days postinoculation

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- RT

reverse transcription

- DAPI

4,6-diamino-phenylindole

- SD

synthetic dextrose

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant no. AGL–2012–32974 to M.G.-G. and Formación del Personal Investigador fellowship no. BES–2013–062674 to R.C.-R.), a Marie Curie International Reintegration grant (grant no. IRG–2010–276771 to M.G.-G.), a European Research Council Starting grant (grant no. ERC–2013–StG–335284 to M.G.-G.), and a Ramón y Cajal fellowship (no. RYC–2010–06363 to M.G.-G.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Andaluz S, Rodríguez-Celma J, Abadía A, Abadía J, López-Millán AF (2009) Time course induction of several key enzymes in Medicago truncatula roots in response to Fe deficiency. Plant Physiol Biochem 47: 1082–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby CA. (1984) Leghemoglobin and Rhizobium respiration. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 35: 443–478 [Google Scholar]

- Askwith C, Eide D, Van Ho A, Bernard PS, Li L, Davis-Kaplan S, Sipe DM, Kaplan J (1994) The FET3 gene of S. cerevisiae encodes a multicopper oxidase required for ferrous iron uptake. Cell 76: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belouchi A, Kwan T, Gros P (1997) Cloning and characterization of the OsNramp family from Oryza sativa, a new family of membrane proteins possibly implicated in the transport of metal ions. Plant Mol Biol 33: 1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier A, Chabaud M, Garcia F, Bécard G, Rosenberg C, Barker DG (2001) Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Medicago truncatula for the study of nitrogen-fixing and endomycorrhizal symbiotic associations. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brear EM, Day DA, Smith PM (2013) Iron: an essential micronutrient for the legume-rhizobium symbiosis. Front Plant Sci 4: 359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin NJ. (1991) Development of the legume root nodule. Annu Rev Cell Biol 7: 191–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito B, Palacios JM, Hidalgo E, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T (1994) Nickel availability to pea (Pisum sativum L.) plants limits hydrogenase activity of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae bacteroids by affecting the processing of the hydrogenase structural subunits. J Bacteriol 176: 5297–5303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailliatte R, Lapeyre B, Briat JF, Mari S, Curie C (2009) The NRAMP6 metal transporter contributes to cadmium toxicity. Biochem J 422: 217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailliatte R, Schikora A, Briat JF, Mari S, Curie C (2010) High-affinity manganese uptake by the metal transporter NRAMP1 is essential for Arabidopsis growth in low manganese conditions. Plant Cell 22: 904–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HP, Walker GC (1998) Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 180: 5183–5191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Wen J, Tadege M, Ratet P, Mysore KS (2011) Reverse genetics in Medicago truncatula using Tnt1 insertion mutants. Methods Mol Biol 678: 179–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Alonso JM, Le Jean M, Ecker JR, Briat JF (2000) Involvement of NRAMP1 from Arabidopsis thaliana in iron transport. Biochem J 347: 749–755 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblaere R, Bytebier B, De Greve H, Deboeck F, Schell J, Van Montagu M, Leemans J (1985) Efficient octopine Ti plasmid-derived vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer to plants. Nucleic Acids Res 13: 4777–4788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth MJ. (1966) Acetylene reduction by nitrogen-fixing preparations from Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochim Biophys Acta 127: 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix DR, Bridgham JT, Broderius MA, Byersdorfer CA, Eide DJ (1994) The FET4 gene encodes the low affinity Fe(II) transport protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 269: 26092–26099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie JA. (2014) Legume nodulation. Curr Biol 24: R184–R190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrnstorfer IA, Geertsma ER, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Dutzler R (2014) Crystal structure of a SLC11 (NRAMP) transporter reveals the basis for transition-metal ion transport. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 990–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes JR, Gros P (2001) Divalent-metal transport by NRAMP proteins at the interface of host-pathogen interactions. Trends Microbiol 9: 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guerrero M, Matthiadis A, Sáez AN, Long TA (2014) Fixating on metals: new insights into the role of metals in nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Front Plant Sci 5: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guerrero M, Raimunda D, Cheng X, Argüello JM (2010) Distinct functional roles of homologous Cu+ efflux ATPases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 78: 1246–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham PH, Vance CP (2003) Legumes: importance and constraints to greater use. Plant Physiol 131: 872–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotz N, Guerinot ML (2006) Molecular aspects of Cu, Fe and Zn homeostasis in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763: 595–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T (2009) Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis (Suppl 1) 30: S162–S173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakoyama T, Niimi K, Yamamoto T, Isobe S, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Kumagai H, Umehara Y, Brossuleit K, et al. (2012) The integral membrane protein SEN1 is required for symbiotic nitrogen fixation in Lotus japonicus nodules. Plant Cell Physiol 53: 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy RW, Holsten RD, Jackson EK, Burns RC (1968) The acetylene-ethylene assay for N2 fixation: laboratory and field evaluation. Plant Physiol 43: 1185–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW (1987) GUS fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J 6: 3901–3907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser BN, Moreau S, Castelli J, Thomson R, Lambert A, Bogliolo S, Puppo A, Day DA (2003) The soybean NRAMP homologue, GmDMT1, is a symbiotic divalent metal transporter capable of ferrous iron transport. Plant J 35: 295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondorosi E, Banfalvi Z, Kondorosi A (1984) Physical and genetic analysis of a symbiotic region of Rhizobium meliloti: identification of nodulation genes. Mol Gen Genet 193: 445–452 [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V, Lelièvre F, Bolte S, Hamès C, Alcon C, Neumann D, Vansuyt G, Curie C, Schröder A, Krämer U, et al. (2005) Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. EMBO J 24: 4041–4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V, Ramos MS, Lelièvre F, Barbier-Brygoo H, Krieger-Liszkay A, Krämer U, Thomine S (2010) Export of vacuolar manganese by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is required for optimal photosynthesis and growth under manganese deficiency. Plant Physiol 152: 1986–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVier K, Day DA, Guerinot ML (1996) Iron uptake by symbisomes from soybean root nodules. Plant Physiol 111: 893–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JE, Pfeiffer WH, Beyer P (2008) Biofortified crops to alleviate micronutrient malnutrition. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RW, Yu Z, Zarkadas CG (1993) The nitrogenase proteins of Rhizobium meliloti: purification and properties of the MoFe and Fe components. Biochim Biophys Acta 1163: 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Usui K, Horie K, Nosaka S, Mizuno N, Obata H (2005) Cloning of three ZIP/Nramp transporter genes from a Ni hyperaccumulator plant Thlaspi japonicum and their Ni2+-transport abilities. Plant Physiol Biochem 43: 793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Kurose T, Hino T, Tanaka K, Kawamukai M, Niwa Y, Toyooka K, Matsuoka K, Jinbo T, Kimura T (2007) Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J Biosci Bioeng 104: 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo Y, Nelson N (2006) The NRAMP family of metal-ion transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763: 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE. (2013) Speak, friend, and enter: signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat Rev Microbiol 11: 252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomen RJFJ, Wu J, Lelièvre F, Blanchet S, Richaud P, Barbier-Brygoo H, Aarts MGM, Thomine S (2009) Functional characterization of NRAMP3 and NRAMP4 from the metal hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. New Phytol 181: 637–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott T, van Dongen JT, Günther C, Krusell L, Desbrosses G, Vigeolas H, Bock V, Czechowski T, Geigenberger P, Udvardi MK (2005) Symbiotic leghemoglobins are crucial for nitrogen fixation in legume root nodules but not for general plant growth and development. Curr Biol 15: 531–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy ME, Liu XF, Culotta VC (2000) Saccharomyces cerevisiae expresses three functionally distinct homologues of the nramp family of metal transporters. Mol Cell Biol 20: 7893–7902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisig O, Zufferey R, Thöny-Meyer L, Appleby CA, Hennecke H (1996) A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol 178: 1532–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Haas B, Finney L, Vogt S, González-Melendi P, Imperial J, González-Guerrero M (2013) Iron distribution through the developmental stages of Medicago truncatula nodules. Metallomics 5: 1247–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosakis A, Köster W (2005) Divalent metal transport in the green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is mediated by a protein similar to prokaryotic Nramp homologues. Biometals 18: 107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth LE, Stacey G (1989) Bacterium release into host cells of nitrogen-fixing soybean nodules: the symbiosome membrane comes from three sources. Eur J Cell Biol 49: 13–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux B, Rodde N, Jardinaud MF, Timmers T, Sauviac L, Cottret L, Carrère S, Sallet E, Courcelle E, Moreau S, et al. (2014) An integrated analysis of plant and bacterial gene expression in symbiotic root nodules using laser-capture microdissection coupled to RNA sequencing. Plant J 77: 817–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio MC, Becana M, Sato S, James EK, Tabata S, Spaink HP (2007) Characterization of genomic clones and expression analysis of the three types of superoxide dismutases during nodule development in Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20: 262–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Argüeso T, Emerich DW, Evans HJ (1979) Hydrogenase system in legume nodules: a mechanism of providing nitrogenase with energy and protection from oxygen damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 86: 259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH Jr, Reddy VS, Tamang DG, Västermark A (2014) The transporter classification database. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D251–D258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiestl RH, Gietz RD (1989) High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet 16: 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöllhorn R, Burris RH (1966) Study of intermediates in nitrogen fixation. Fed Proc 25: 710 [Google Scholar]

- Segond D, Dellagi A, Lanquar V, Rigault M, Patrit O, Thomine S, Expert D (2009) NRAMP genes function in Arabidopsis thaliana resistance to Erwinia chrysanthemi infection. Plant J 58: 195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F, Fink GR, Hicks JB (1986) Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press, Plainview, NY [Google Scholar]

- Smil V. (1999) Nitrogen in crop production: an account of global flows. Global Biogeochem Cycles 13: 647–662 [Google Scholar]

- Sprent JI. (2007) Evolving ideas of legume evolution and diversity: a taxonomic perspective on the occurrence of nodulation. New Phytol 174: 11–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F, Supekova L, Nelson H, Nelson N (1996) A yeast manganese transporter related to the macrophage protein involved in conferring resistance to mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5105–5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadege M, Wen J, He J, Tu H, Kwak Y, Eschstruth A, Cayrel A, Endre G, Zhao PX, Chabaud M, et al. (2008) Large-scale insertional mutagenesis using the Tnt1 retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J 54: 335–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takanashi K, Yokosho K, Saeki K, Sugiyama A, Sato S, Tabata S, Ma JF, Yazaki K (2013) LjMATE1: a citrate transporter responsible for iron supply to the nodule infection zone of Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell Physiol 54: 585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Robson AD, Dilworth MJ (1990) The role of iron in nodulation and nitrogen fixation in Lupinus angustifolius L. New Phytol 114: 173–182 [Google Scholar]

- Tang CX, Robson AD, Dilworth MJ, Kuo J (1992) Microscopic evidence on how iron-deficiency limits nodule initiation in Lupinus angustifolius l. New Phytol 121: 457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry RE, Soerensen KU, Jolley VD, Brown JC (1991) The role of active Bradyrhizobium japonicum in iron stress response of soy-beans. Plant Soil 130: 225–230 [Google Scholar]

- Thomine S, Wang R, Ward JM, Crawford NM, Schroeder JI (2000) Cadmium and iron transport by members of a plant metal transporter family in Arabidopsis with homology to Nramp genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4991–4996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers ACJ, Soupène E, Auriac MC, de Billy F, Vasse J, Boistard P, Truchet G (2000) Saprophytic intracellular rhizobia in alfalfa nodules. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13: 1204–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udvardi M, Poole PS (2013) Transport and metabolism in legume-rhizobia symbioses. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64: 781–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rhijn P, Vanderleyden J (1995) The Rhizobium-plant symbiosis. Microbiol Rev 59: 124–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasse J, de Billy F, Camut S, Truchet G (1990) Correlation between ultrastructural differentiation of bacteroids and nitrogen fixation in alfalfa nodules. J Bacteriol 172: 4295–4306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernoud V, Journet EP, Barker DG (1999) MtENOD20, a Nod factor-inducible molecular marker for root cortical cell activation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 12: 604–614 [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Grotz N, Dédaldéchamp F, Gaymard F, Guerinot ML, Briat JF, Curie C (2002) IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14: 1223–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D (2003) An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J 33: 949–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N, Sasaki A, Xia JX, Yokosho K, Ma JF (2013) A node-based switch for preferential distribution of manganese in rice. Nat Commun 4: 2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhang W, Dong H, Zhang Y, Lv K, Wang D, Lian X (2013) OsNRAMP3 is a vascular bundles-specific manganese transporter that is responsible for manganese distribution in rice. PLoS ONE 8: e83990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.