Abstract

Upon infection, the genomes of herpesviruses undergo a striking transition from a non-nucleosomal structure to a chromatin structure. The rapid assembly and modulation of nucleosomes during the initial stage of infection results in an overlay of complex regulation that requires interactions of a plethora of chromatin modulation components.

For herpes simplex virus, the initial chromatin dynamic is dependent on viral and host cell transcription factors and coactivators that mediate the balance between heterochromatic suppression of the viral genome and the euchromatin transition that allows and promotes the expression of viral immediate early genes.

Strikingly similar to lytic infection, in sensory neurons this dynamic transition between heterochromatin and euchromatin governs the establishment, maintenance, and reactivation from the latent state. Chromatin dynamics in both the lytic infection and latency-reactivation cycles provides opportunities to shift the balance using small molecule epigenetic modulators to suppress viral infection, shedding, and reactivation from latency.

Keywords: herpes simplex virus, chromatin, demethylase, LSD1, JMJD2, HCF-1, latency

Upon infection of a cell, the genomes of herpesviruses undergo a striking transition from a non-nucleosomal state in the viral capsid to a chromatin state that resembles the host cell’s genome. While previously considered to be inconsequential for viral lytic infection, it has become clear that the assembly, modification, and remodeling of viral chromatin plays a critical regulatory role in determining the progression of infection.

Fates of infecting viral genomes

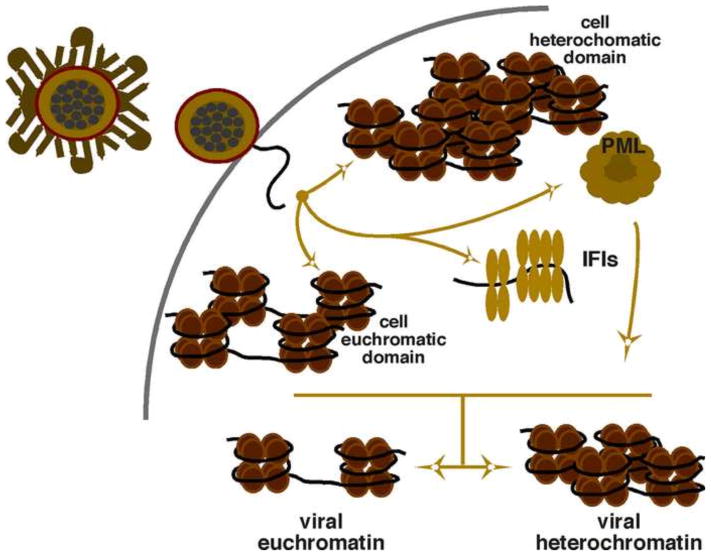

Post entry, the viral capsid is transported to the nuclear pore where the genome is released from its compacted state into the cell nucleus. At this point, the fate of the genome may be highly dependent upon the subnuclear localization or microenvironment that is enriched in either repressive cofactors or transcriptional activators and coactivators (Silva et al., 2008). This review will focus on components that are directly involved in the initial modulation of the viral chromatin state. However, it is important to point out that multiple interactions of the host cell and virus play roles in determining the balance between heterochromatic suppression and euchromatic activation of the population of infecting viral genomes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Fates of infecting HSV genomes.

Complex cell-viral interactions determine the fate of an individual non-chromatinized genome as it is released into the nucleus. The localization of the infecting genome to subnuclear domains enriched in factors promoting heterochromatin or euchromatin may be an important determinant of the state of the chromatin assembled on the viral genome. In addition, sequestering by PML bodies or suppression by assembled IFIs (interferon-induced factors) may promote subsequent nucleosome assembly into repressive heterochromatic structures. The initial state of the viral chromatin appears to be dynamic and ultimately modulated by chromatin machinery.

Two classes of histone chaperone complexes are involved in replication-independent deposition of nucleosomes containing histone H3.3. The heterochromatin associated Daxx (death domain-associated protein) and the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeler ATRX (alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked) appear to be involved in nucleosome assembly that ultimately progresses to a heterochromatic state (Drane et al., 2010; Everett, 2013; Ishov et al., 2004; Lukashchuk and Everett, 2010). While it has not been directly demonstrated that this chaperone/remodeler complex promotes heterochromatic assembly on the HSV genome, Daxx/ATRX is involved in the initial repression of the infecting viral genome (Lukashchuk and Everett, 2010). In contrast, the chaperones HIRA (histone cell cycle regulator) and ASF1a (anti-silencing factor) are implicated in H3.3 assembly that ultimately promotes viral gene expression (Oh et al., 2012; Placek et al., 2009). The localization of the infecting genome to sites enriched for either of these chaperone complexes and the associated chromatin modulation components may determine the initial chromatin state.

In addition to subnuclear microenvironments, the association or juxtaposition of viral genomes with PML (promyelocytic leukemia) nuclear bodies plays a role in the initial response to the viral genome (Everett, 2013). Interestingly, there is a diverse population of PML bodies (Sahin et al., 2014) including those proximal to pericentric regions that are enriched in the repressive cofactors Daxx and ATRX (Chang et al., 2013; Ishov et al., 2004). These bodies maintain the heterochromatic structures of the region’s repeats and may function similarly to repress a population of infecting genomes.

Antiviral responses, such as the recognition of non-chromatinized viral DNA by IFIs (interferon inducible proteins, i.e. IFI16) can prevent the binding of transcriptional activators to the viral genome by the formation of oligomer structures. This process has been linked to the ultimate heterochromatic suppression of the HSV genome (Johnson et al., 2014; Orzalli et al., 2013) although the mechanism(s) by which IFIs are coupled to chromatin modulation are unclear and may be an indirect consequence of inhibiting the association of transcriptional activators (e.g. Sp1) with the genome (Caposio et al., 2007; Gariano et al., 2012).

Multiple states of HSV chromatin

Two important observations were made that illustrated the complex patterns of HSV chromatin upon initial infection. While previous studies had suggested that the levels of nucleosomes associated with the viral genome were low or inconsequential, it was subsequently demonstrated that the genome was in fact associated with canonically spaced nucleosomes (Lacasse and Schang, 2010, 2012). These studies revealed that rapid remodeling of viral associated nucleosomes, likely based upon high-level acetylation of histones, resulted in technical underrepresentation in ChIP assays or when using standard micrococcal nuclease protection protocols. In contrast to this “euchromatic” state, genomes associated with heterochromatic chromatin structures were also observed upon initial infection (Liang et al., 2009; Narayanan et al., 2007; Silva et al., 2008). The levels of repressive heterochromatic histone marks associated with the viral genome were readily detected at the initial stage of infection but were rapidly reduced concomitant with the expression of viral IE genes (Liang et al., 2009).

Thus, two opposing states of viral chromatin were found in the population of lytically infected cells. These observations suggested that the fate of a given infecting genome is likely determined by multiple opposing factors and that the initial state of the viral chromatin is relatively dynamic.

Activators and coactivators controlling HSV IE gene expression

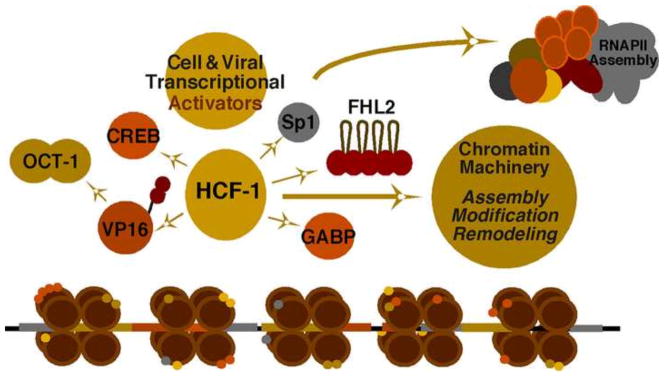

To a large extent, the productive infection is dependent on the successful activation of viral immediate early (IE) gene transcription. HSV IE gene promoter regulatory regions are designed to respond to multiple transcription factors and transcriptional coactivators that function cooperatively to drive high-level expression in a rapid manner (Fig. 2) (Knipe et al., 2013; Kristie et al., 2010; Vogel and Kristie, 2013). During lytic infection, the viral encoded IE activator VP16 is released from the tegument structure of the infecting virus and is recruited to viral IE enhancer elements by interaction with the cellular POU domain protein Oct-1. Additional cellular DNA-binding transcription factors such as Sp1 (specificity protein 1) and GABP (GA-binding protein) contribute to synergistic activation of transcription, although these factors can also promote IE gene expression in the absence of the VP16 viral activator.

Figure 2. Viral and cellular factors mediating HSV IE gene expression.

Multiple classes of cellular DNA-binding transcription factors cooperate with the viral IE activator VP16 to drive high-level expression of viral IE genes. HCF-1 is a central component required for mediating transcriptional potential of these factors by coupling interactions with cellular chromatin modulation machinery.

The central component of the IE gene regulatory paradigm is the cellular coactivator HCF-1 (Host Cell Factor-1) (Narayanan et al., 2005). HCF-1 interacts with many of the transcription factors that bind the IE promoter regions and it is critical for the transcriptional potential of these factors (Kristie et al., 2010). In recent years, it has become clear that the protein is a component of or associated with multiple chromatin modulation complexes and functions mechanistically to couple DNA binding transcription factors to cellular chromatin modulation complexes (Knipe et al., 2013; Kristie et al., 2010; Narayanan et al., 2007; Vogel and Kristie, 2013; Wysocka et al., 2003). These complexes play a role in modulating the dynamic between heterochromatic suppression and euchromatic activation of the viral genome.

The dynamic state of HSV chromatin

Components mediating heterochromatic suppression of the HSV genome

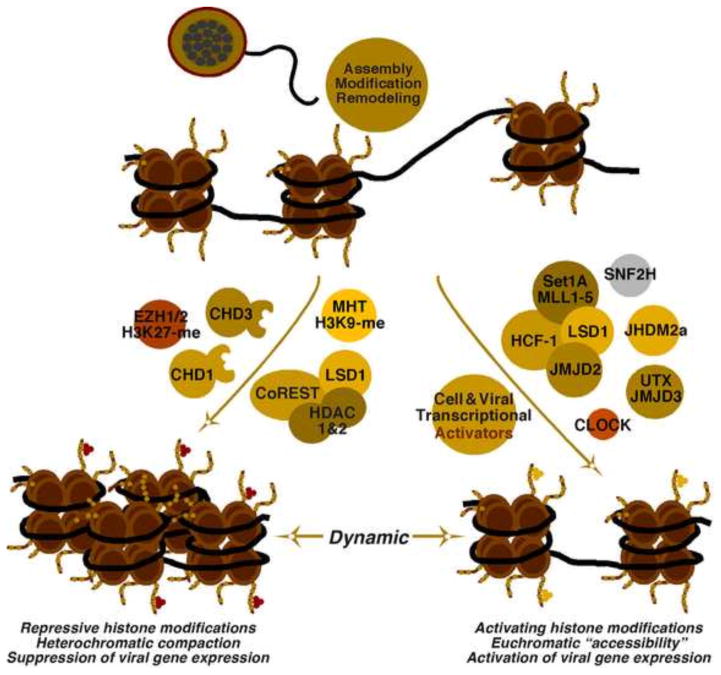

Assembly of nucleosomes on the viral genome progresses to a dynamic between factors that promote suppressive heterochromatin and those that promote a euchromatic structure that allows viral gene expression (Fig. 3). Repressive H3K9- and H3K27-methylation can be detected on nucleosomes assembled on the viral genome at early times post infection (Liang et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2008). However, there has not yet been a specific identification or demonstration of the methyltransferases involved.

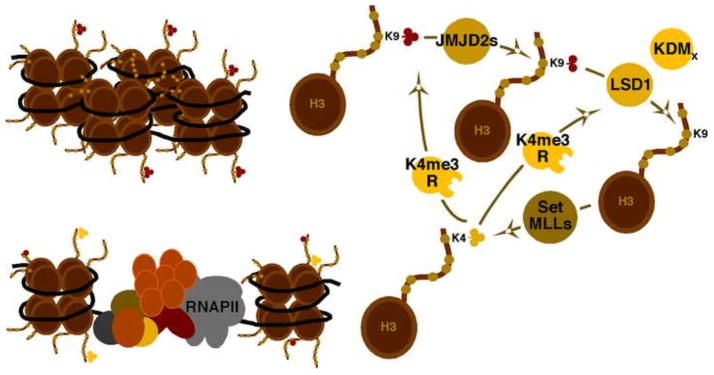

Figure 3. The dynamic state of HSV chromatin during initiation of lytic infection.

(A) Assembly of nucleosomes on the viral genome leads to a dynamic state mediated by factors that promote the formation of repressed heterochromatin (Left) and those that reduce the levels of repressive histone marks associated with the viral genome and promote the formation of a euchromatic chromatin structure (Right).

In addition to these epigenetic writers, the histone reader-remodeler CHD3 (Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 3) plays an important role in repression of a large percentage of infecting viral genomes (Arbuckle and Kristie, 2014). This protein recognizes both H3K9-me3 and H3K27-me3 repressive marks and promotes the compaction of viral chromatin. The role of CHD3 in this process may be combination of its involvement in remodeling nucleosomes to canonical spacing/density and its recruitment of factors involved in the formation/maintenance of heterochromatin (i.e. KAP-1; KRAB-Associated Protein 1; HDAC1/2, Histone Deacetylase 1/2; H3K9-methyltransferase SETDB1; HP1, heterochromatin protein 1) (Goodarzi et al., 2011; Schultz et al., 2002; Schultz et al., 2001).

The lysine-specific demethylase LSD1 (KDM1) plays both repressive and activating roles in the regulation of cellular gene expression. Like many chromatin modulation enzymes, LSD1 demethylates multiple targets including the euchromatic H3K4-me2/1 and the heterochromatic H3K9-me2/1 marks. The specificity or targeting of the enzyme is, to some extent, dependent on the associated cofactors. In the repressive CoREST complex, LSD1 is associated with HDAC1/2 and the combination of the activities in this complex promotes suppression (Lee et al., 2005; Ouyang et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2005). However, in LSD1 deleted embryonic stem cells (ES cells), global levels of H3K4-methylation are not altered while the levels of histone acetylation are significantly increased (Foster et al., 2010). Thus, it is likely that HDAC1/2 are the most significant repressive components in this complex. During HSV infection, the CoREST complex is involved in suppression of the Early and Late gene classes but does not appear to significantly impact IE expression (Gu et al., 2005; Gu and Roizman, 2007). Whether the demethylase activity of LSD1 is important in this context, relative to the activities of the associated HDACs, remains unclear. Strikingly, the viral IE protein ICP0 targets the CoREST complex, resulting in dissociation of the components and relocalization of HDAC1/2 to the cytoplasm of the infected cell (Gu et al., 2005; Gu and Roizman, 2007). This viral-directed modulation of the complex is one mechanism by which ICP0 promotes histone acetylation (Cliffe and Knipe, 2008) and the expression of HSV genes.

Components mediating euchromatic activation of HSV gene expression

As noted above, the coactivator HCF-1 plays a central role in activation of HSV IE gene expression via coupling of DNA-binding transcriptional activators to chromatin modulation complexes. To promote viral gene expression, HCF-1 is recruited to the viral IE regulatory-promoter domains as part of a complex containing multiple chromatin modulation components that shift the balance of the viral chromatin state from heterochromatic to euchromatic. The HCF-1 complex contains histone H3K9-demethylases (LSD1 and members of the JMJD2 family) that prevent the accumulation of the repressive methylation mark and histone H3K4-methyltransferases that install the transcriptionally permissive H3K4-me3 mark (Set and MLL complexes) (Huang et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2013b; Liang et al., 2009; Narayanan et al., 2007; Wysocka et al., 2003).

In contrast to its repressive role in the CoREST complex, LSD1 also functions as an activator by removal of repressive heterochromatic H3K9-me2/1 marks. This activity was originally described in studies of NHR (nuclear hormone receptor) mediated transcription, where LSD1 acts to reduce H3K9-me2/1 and promote transcription of NHR target genes (Metzger et al., 2005). However the enzyme only removes H3K9-me2/1 and thus members of the second class of H3K9-demethylase (JMJD2 family) are required to remove the tri-methyl (Fig. 4) (Wissmann et al., 2007). Removal of H3K9-methylation permits the “unmodified histone” to be methylated at the activating H3K4 site by the Set or MLL complexes. This cycle can be amplified by H3K4-me3 readers that recognize this activating mark and promote the further removal of the repressive methylation marks (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Removal of repressive histone H3-lysine 9-me3 requires the concerted activities of two classes of demethylase.

JMJD2s remove H3K9-me3/2 while LSD1 removes H3K9-me2/1. Removal of H3K9-me3 allows for euchromatic methylation of H3K4 by the Set or MLL complexes. This cycle can be promoted by chromatin readers that recognize the active mark (K4me3R) and enhance the activity of the demethylases.

The coupling of multiple chromatin modulation components into specific complexes, as illustrated by the HCF-1 complex, is a common theme in chromatin biology where linkages between required enzymatic activities and recognition activities efficiently drive changes in chromatin structure. In HSV infection, the requirement for these activities supports the concept that the chromatin state of the viral genome is dynamic and is modulated during the initiation of infection.

In addition to the HCF-1 associated chromatin regulatory proteins, several chromatin modulation components have been identified that impact viral gene expression, presumably via modulation of viral chromatin:

JHDM2a, a second H3K9-me2/1 demethylase was identified in an siRNA library screen in U2OS cells as being required for efficient IE gene expression (Oh et al., 2014). As the specificity of JHDM2a is similar to LSD1, it raises the possibilities that (i) multiple enzymes may target this repressive mark; (ii) there is a cell-type specificity that is based upon the expression and availability of a particular enzyme; and/or (iii) the enzymes may also have non-overlapping protein targets.

The nucleosome remodeler SNF2H is recruited to viral IE gene promoters and promotes IE gene expression (Bryant et al., 2011). This remodeler complex promotes nucleosome assembly, movement, and positioning as well as incorporation of histone H1 and H2a variants that promote rapid remodeling (Alvarez-Saavedra et al., 2014). Interestingly, SNF2H accumulates in viral replication factories suggesting multiple roles in modulating viral chromatin at different stages of infection (Bryant et al., 2011).

Acetylated histones are associated with the viral genome and histone deacetylases (HDACs) play a role in suppressing viral infection. In addition, as noted above, ICP0 promotes histone acetylation (Cliffe and Knipe, 2008), at least in part, via inhibition of HDAC1/2 (Gu et al., 2005). These observations suggest that histone acetylation should play an important role in promoting viral infection, likely via promoting nucleosome remodeling. However, infection of cells lacking or depleted of the canonical p300, CBP, PCAF, and GCN5 HAT complexes did not impact viral gene expression although these proteins were recruited to IE gene promoters by the VP16 IE activator (Kutluay et al., 2009). Subsequently, CLOCK, the circadian rhythm histone H3/H4 acetyltransferase, was shown to be important for the expression of all classes of viral genes, was stabilized during infection, and was recruited to ND10 bodies (Kalamvoki and Roizman, 2010). Interestingly, overexpression of CLOCK can compensate for the lack of the viral ICP0 protein, suggesting that it contributes to the acetylation of viral-associated histones.

Given the complex nature of chromatin modulation and the lessons learned from cellular chromatin biology, there are many components and pathways that remain to be identified to account for the viral chromatin dynamics that occur throughout lytic infection. Some of the enzymatic activities that are critical for modification of histones associated with the viral genome have been identified. However, little is known concerning the components that determine the specificity of these modification enzymes, recognize the specific histone marks (Readers), and determine the downstream molecular events leading to suppression or activation of viral gene expression.

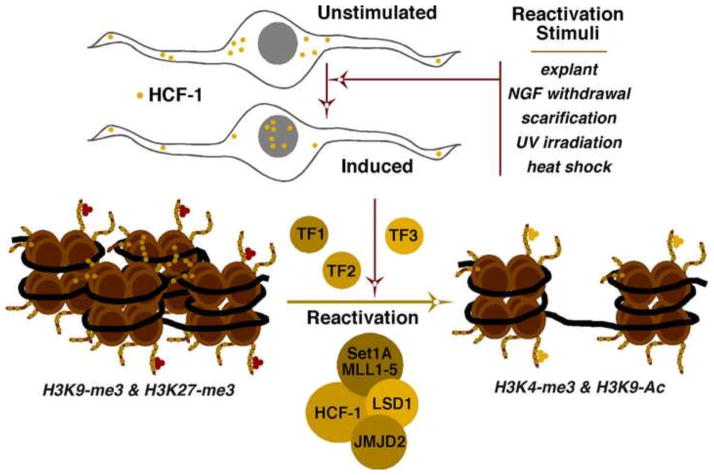

The HCF-1 chromatin modulation complex in HSV reactivation from latency

During latency in sensory neurons, chromatin associated with the viral genome is heterochromatic and both H3K9- and H3K27-methylation marks are present (Cliffe et al., 2013; Cliffe et al., 2009; Kwiatkowski et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005). The only clear exception to this is the LAT locus, which is expressed during latency and is enriched in euchromatic marks (H3K9/14-acetyl and H3K4-me3) (Amelio et al., 2006; Bloom et al., 2010; Creech and Neumann, 2010; Knipe and Cliffe, 2008; Kubat et al., 2004; Neumann et al., 2007). Interestingly, H3K27-me3 marks appear to be established on genomes following initial silencing of lytic gene expression, suggesting that the PRC2 complex (polycomb repressive complex 2) may play a more important role in secondary suppression rather than initial establishment (Cliffe et al., 2013). Primary suppression of the viral genome may be a consequence of several repressive factors including the REST/CoREST complex (Du et al., 2010). Upon stimulation resulting in reactivation, there is a transition from the heterochromatic to the euchromatic chromatin associated with the viral lytic genes (Amelio et al., 2006; Bloom et al., 2010; Creech and Neumann, 2010; Knipe and Cliffe, 2008; Neumann et al., 2007). Thus, modulation of this transition is an important regulatory component of the viral lytic-latency cycle.

As described, the HCF-1 coactivator complex containing histone demethylases and methyltransferases is important for driving viral gene expression during the initiation of lytic infection. Strikingly, HCF-1 is enriched in the cytoplasm of unstimulated sensory neurons where the virus establishes latency and is rapidly transported to the nucleus upon stimulation that results in viral reactivation (Fig. 5) (Kristie et al., 1999). HCF-1 transport coincides with occupancy at viral IE gene promoters (Whitlow and Kristie, 2009), although the DNA-binding factors that mediate HCF-1 recruitment remain unknown. These observations led to a model that HCF-1 transport is an event that is critical to initiation of reactivation, likely via modulation of the viral chromatin state (Kristie et al., 2010; Kristie et al., 1999). The model is further supported by the use of inhibitors of the HCF-1-associated H3K9 demethylases (LSD1 and JMJD2s) in a mouse explant model system of viral reactivation. In the presence of either class of inhibitor, viral lytic gene expression and consequently viral reactivation is potently suppressed (Liang et al., 2013a; Liang et al., 2013b; Liang et al., 2009).

Figure 5. The transcriptional coactivator HCF-1 and associated chromatin modulation components plays a role in HSV reactivation from latency.

During latency, nucleosomes associated with the viral genome have characteristic heterochromatic methylation marks (H3K9-me3 and H3K27-me3). Reactivation is associated with a transition to euchromatic marks (H3K4-me3 and H3K9-Ac). HCF-1 is sequestered in the cytoplasm of unstimulated sensory neurons but is rapidly transported to the nucleus upon stimulation that results in HSV reactivation from latency. While the specific transcription factors that mediate HCF-1 recruitment to the viral genome during reactivation are unknown (TF1, TF2, TF3), efficient reactivation requires the activities of the HCF-1 associated histone demethylases JMJD2s and LSD1.

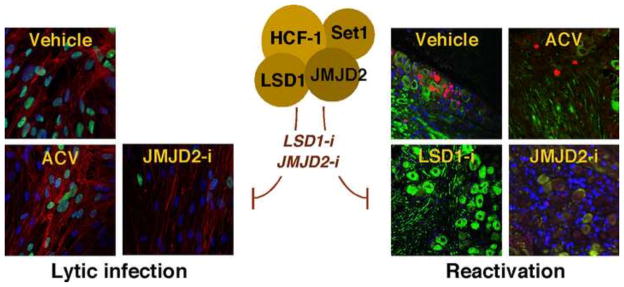

Epigenetic suppression of HSV infection and reactivation

Inhibition of either LSD1 or JMJD2 activities can suppress both viral lytic infection and reactivation in in vitro model systems (Fig. 6). The results suggest that epigenetic modulation of viral infection can be an approach to control persistent viruses. This concept was recently demonstrated using an inhibitor of LSD1 in three primary models of HSV disease. Here, inhibition of LSD1 reduced viral primary infection, subclinical shedding, and spontaneous reactivation. Strikingly, the reduction in HSV shedding and clinical recurrence was correlated with enhanced epigenetic suppression of the viral genome in sensory neurons (Hill et al., 2014). The ability to modulate the chromatin state of the viral genome suggests that the genome is not static, but rather undergoes chromatin dynamics even during latency. Furthermore, this indicates that chromatin state of the viral genome is a determining factor in the viral lytic infection and latency-reactivation cycles.

Figure 6. Epigenetic suppression of HSV infection and reactivation.

The use of small molecule inhibitors of required chromatin modulation components represents a new avenue for antivirals. Inhibition of the activities of the HCF-1 associated demethylases JMJD2s or LSD1 suppresses viral lytic infection and reactivation from latency. (Left) Cells treated with a JMDJ2 inhibitor (JMJD2-i) exhibit a significantly reduced level of lytic infection (green cells) relative to Vehicle or ACV (acyclovir). (Right) Latently infected mouse trigeminal ganglia explanted for 48hrs in the presence of inhibitors of LSD1 (LSD1-i) or JMJD2s (JMJD2-i) have reduced numbers of neurons undergoing productive reactivation (red cells) relative to ganglia treated with Vehicle (spreading infection) or ACV (individual primary reactivating neurons).

A recent focus on the development of epigenetic pharmaceuticals for the treatment of specific cancers (Copeland et al., 2010; Hatzimichael and Crook, 2013; Helin and Dhanak, 2013; Hojfeldt et al., 2013; Lohse et al., 2011; Nebbioso et al., 2012) has produced inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases, HDACs (class-specific and pan), histone demethylases, bromodomain histone recognition proteins, and histone methyltransferases (i.e. EZH2). There are a number of challenges to this approach including (i) the specificity involved in targeting a particular member of a highly conserved family of enzymes and (ii) minimizing global impacts on the cell/organism. However, in disease states including recurrent/persistent viral infections, targeting chromatin modulation components that are critical for initiation of viral infection or recurrence represents a new approach to control the disease states.

In HIV biology, HDAC inhibitors are being tested as an approach to induce latent viral genomes (Choudhary and Margolis, 2011; Shirakawa et al., 2013). In combination with HAART therapy to suppress viral spread, infected cells would be cleared by the immune response. However, given that there are multiple anatomical sites/reservoirs of viral latency including the CNS (Alexaki et al., 2008; Churchill et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2014; Lewin et al., 2011), it may be more clinically appropriate to utilize epigenetic suppression as a means to control the virus.

Summary

The complex interactions of the host cell and infecting viral genome include chromatin dynamics that either result in suppression of the vial lytic gene expression or the progression to a permissive nucleosome structure that promotes viral IE gene transcription. For HSV, there is now a basic understanding of the assembly and modulation of this chromatin regulatory overlay. However, it is also clear from chromatin biology that there are many undefined modulation components that must regulate HSV chromatin. Understanding the roles and impacts of the modulation machinery provides insights into viral-host interactions and could provide additional targets for novel antivirals.

Research Highlights.

Chromatin modulation regulates HSV infection and latency-reactivation cycles

Multiple factors impact the initial chromatin state of the infecting viral genome

Initiation of infection is impacted by a heterochromatic-euchromatic dynamic

Targeting required epigenetic enzymes suppresses HSV infection and reactivation

Acknowledgments

Due to the focused nature of this review, it was not possible to cite all of the important primary contributions to this field. I thank J.H. Arbuckle and A.M. Turner for constructive comments on this manuscript. Studies of the Molecular Genetics Section and the preparation of this review were supported by the Intramural Research Division of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexaki A, Liu Y, Wigdahl B. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 and their role in viral persistence. Current HIV research. 2008;6:388–400. doi: 10.2174/157016208785861195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Saavedra M, De Repentigny Y, Lagali PS, Raghu Ram EV, Yan K, Hashem E, Ivanochko D, Huh MS, Yang D, Mears AJ, Todd MA, Corcoran CP, Bassett EA, Tokarew NJ, Kokavec J, Majumder R, Ioshikhes I, Wallace VA, Kothary R, Meshorer E, Stopka T, Skoultchi AI, Picketts DJ. Snf2h-mediated chromatin organization and histone H1 dynamics govern cerebellar morphogenesis and neural maturation. Nature communications. 2014;5:4181. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amelio AL, Giordani NV, Kubat NJ, O’Neil JE, Bloom DC. Deacetylation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer and a decrease in LAT abundance precede an increase in ICP0 transcriptional permissiveness at early times postexplant. J Virol. 2006;80:2063–2068. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.2063-2068.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JH, Kristie TM. Epigenetic repression of herpes simplex virus infection by the nucleosome remodeler CHD3. MBio. 2014;5:e01027–01013. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01027-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DC, Giordani NV, Kwiatkowski DL. Epigenetic regulation of latent HSV-1 gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KF, Colgrove RC, Knipe DM. Cellular SNF2H chromatin-remodeling factor promotes herpes simplex virus 1 immediate-early gene expression and replication. MBio. 2011;2:e00330–00310. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00330-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caposio P, Gugliesi F, Zannetti C, Sponza S, Mondini M, Medico E, Hiscott J, Young HA, Gribaudo G, Gariglio M, Landolfo S. A novel role of the interferon-inducible protein IFI16 as inducer of proinflammatory molecules in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33515–33529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang FT, McGhie JD, Chan FL, Tang MC, Anderson MA, Mann JR, Andy Choo KH, Wong LH. PML bodies provide an important platform for the maintenance of telomeric chromatin integrity in embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4447–4458. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary SK, Margolis DM. Curing HIV: Pharmacologic approaches to target HIV-1 latency. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2011;51:397–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill MJ, Cowley DJ, Wesselingh SL, Gorry PR, Gray LR. HIV-1 transcriptional regulation in the central nervous system and implications for HIV cure research. Journal of neurovirology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0271-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe AR, Coen DM, Knipe DM. Kinetics of facultative heterochromatin and polycomb group protein association with the herpes simplex viral genome during establishment of latent infection. MBio. 2013:4. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00590-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe AR, Garber DA, Knipe DM. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript promotes the formation of facultative heterochromatin on lytic promoters. J Virol. 2009;83:8182–8190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00712-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe AR, Knipe DM. Herpes simplex virus ICP0 promotes both histone removal and acetylation on viral DNA during lytic infection. J Virol. 2008;82:12030–12038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01575-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland RA, Olhava EJ, Scott MP. Targeting epigenetic enzymes for drug discovery. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2010;14:505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creech CC, Neumann DM. Changes to euchromatin on LAT and ICP4 following reactivation are more prevalent in an efficiently reactivating strain of HSV-1. PloS one. 2010;5:e15416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du T, Zhou G, Khan S, Gu H, Roizman B. Disruption of HDAC/CoREST/REST repressor by dnREST reduces genome silencing and increases virulence of herpes simplex virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15904–15909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010741107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett RD. The spatial organization of DNA virus genomes in the nucleus. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003386. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CT, Dovey OM, Lezina L, Luo JL, Gant TW, Barlev N, Bradley A, Cowley SM. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 regulates the embryonic transcriptome and CoREST stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4851–4863. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00521-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariano GR, Dell’Oste V, Bronzini M, Gatti D, Luganini A, De Andrea M, Gribaudo G, Gariglio M, Landolfo S. The intracellular DNA sensor IFI16 gene acts as restriction factor for human cytomegalovirus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002498. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi AA, Kurka T, Jeggo PA. KAP-1 phosphorylation regulates CHD3 nucleosome remodeling during the DNA double-strand break response. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:831–839. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray LR, Roche M, Flynn JK, Wesselingh SL, Gorry PR, Churchill MJ. Is the central nervous system a reservoir of HIV-1? Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:552–558. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Liang Y, Mandel G, Roizman B. Components of the REST/CoREST/histone deacetylase repressor complex are disrupted, modified, and translocated in HSV-1-infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7571–7576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502658102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus-infected cell protein 0 blocks the silencing of viral DNA by dissociating histone deacetylases from the CoREST-REST complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17134–17139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707266104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzimichael E, Crook T. Cancer epigenetics: new therapies and new challenges. Journal of drug delivery. 2013;2013:529312. doi: 10.1155/2013/529312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helin K, Dhanak D. Chromatin proteins and modifications as drug targets. Nature. 2013;502:480–488. doi: 10.1038/nature12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Quenelle DC, Cardin RD, Vogel JL, Clement C, Bravo FJ, Foster TP, Bosch-Marce M, Raja P, Lee JS, Bernstein DI, Krause PR, Knipe DM, Kristie TM. Inhibition of LSD1 reduces herpesvirus infection, shedding, and recurrence by promoting epigenetic suppression of viral genomes. Science translational medicine. 2014:6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojfeldt JW, Agger K, Helin K. Histone lysine demethylases as targets for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:917–930. doi: 10.1038/nrd4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Kent JR, Placek B, Whelan KA, Hollow CM, Zeng PY, Fraser NW, Berger SL. Trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 by Set1 in the lytic infection of human herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol. 2006;80:5740–5746. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00169-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishov AM, Vladimirova OV, Maul GG. Heterochromatin and ND10 are cell-cycle regulated and phosphorylation-dependent alternate nuclear sites of the transcription repressor Daxx and SWI/SNF protein ATRX. Journal of cell science. 2004;117:3807–3820. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KE, Bottero V, Flaherty S, Dutta S, Singh VV, Chandran B. IFI16 Restricts HSV-1 Replication by Accumulating on the HSV-1 Genome, Repressing HSV-1 Gene Expression, and Directly or Indirectly Modulating Histone Modifications. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004503. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamvoki M, Roizman B. Circadian CLOCK histone acetyl transferase localizes at ND10 nuclear bodies and enables herpes simplex virus gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17721–17726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012991107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe DM, Cliffe A. Chromatin control of herpes simplex virus lytic and latent infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe DM, Lieberman PM, Jung JU, McBride AA, Morris KV, Ott M, Margolis D, Nieto A, Nevels M, Parks RJ, Kristie TM. Snapshots: chromatin control of viral infection. Virology. 2013;435:141–156. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristie TM, Liang Y, Vogel JL. Control of alpha-herpesvirus IE gene expression by HCF-1 coupled chromatin modification activities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristie TM, Vogel JL, Sears AE. Nuclear localization of the C1 factor (host cell factor) in sensory neurons correlates with reactivation of herpes simplex virus from latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1229–1233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubat NJ, Amelio AL, Giordani NV, Bloom DC. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer/rcr is hyperacetylated during latency independently of LAT transcription. J Virol. 2004;78:12508–12518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12508-12518.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutluay SB, DeVos SL, Klomp JE, Triezenberg SJ. Transcriptional coactivators are not required for herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early gene expression in vitro. J Virol. 2009;83:3436–3449. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02349-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DL, Thompson HW, Bloom DC. The polycomb group protein Bmi1 binds to the herpes simplex virus 1 latent genome and maintains repressive histone marks during latency. Journal of virology. 2009;83:8173–8181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00686-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacasse JJ, Schang LM. During lytic infections, herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is in complexes with the properties of unstable nucleosomes. J Virol. 2010;84:1920–1933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01934-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacasse JJ, Schang LM. Herpes simplex virus 1 DNA is in unstable nucleosomes throughout the lytic infection cycle, and the instability of the nucleosomes is independent of DNA replication. J Virol. 2012;86:11287–11300. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01468-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Wynder C, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. An essential role for CoREST in nucleosomal histone 3 lysine 4 demethylation. Nature. 2005;437:432–435. doi: 10.1038/nature04021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin SR, Evans VA, Elliott JH, Spire B, Chomont N. Finding a cure for HIV: will it ever be achievable? Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011;14:4. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Quenelle D, Vogel JL, Mascaro C, Ortega A, Kristie TM. A novel selective LSD1/KDM1A inhibitor epigenetically blocks herpes simplex virus lytic replication and reactivation from latency. MBio. 2013a;4:e00558–00512. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00558-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Vogel JL, Arbuckle JH, Rai G, Jadhav A, Simeonov A, Maloney DJ, Kristie TM. Targeting the JMJD2 histone demethylases to epigenetically control herpesvirus infection and reactivation from latency. Science translational medicine. 2013b;5:167ra165. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Vogel JL, Narayanan A, Peng H, Kristie TM. Inhibition of the histone demethylase LSD1 blocks alpha-herpesvirus lytic replication and reactivation from latency. Nat Med. 2009;15:1312–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse B, Kristensen JL, Kristensen LH, Agger K, Helin K, Gajhede M, Clausen RP. Inhibitors of histone demethylases. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2011;19:3625–3636. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashchuk V, Everett RD. Regulation of ICP0-null mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by ND10 components ATRX and hDaxx. J Virol. 2010;84:4026–4040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02597-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger E, Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Schneider R, Peters AH, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schule R. LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature. 2005;437:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature04020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan A, Nogueira ML, Ruyechan WT, Kristie TM. Combinatorial transcription of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus immediate early genes is strictly determined by the cellular coactivator HCF-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1369–1375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan A, Ruyechan WT, Kristie TM. The coactivator host cell factor-1 mediates Set1 and MLL1 H3K4 trimethylation at herpesvirus immediate early promoters for initiation of infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10835–10840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704351104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebbioso A, Carafa V, Benedetti R, Altucci L. Trials with ‘epigenetic’ drugs: an update. Mol Oncol. 2012;6:657–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann DM, Bhattacharjee PS, Giordani NV, Bloom DC, Hill JM. In vivo changes in the patterns of chromatin structure associated with the latent herpes simplex virus type 1 genome in mouse trigeminal ganglia can be detected at early times after butyrate treatment. J Virol. 2007;81:13248–13253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01569-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HS, Bryant KF, Nieland TJ, Mazumder A, Bagul M, Bathe M, Root DE, Knipe DM. A targeted RNA interference screen reveals novel epigenetic factors that regulate herpesviral gene expression. MBio. 2014;5:e01086–01013. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01086-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J, Ruskoski N, Fraser NW. Chromatin assembly on herpes simplex virus 1 DNA early during a lytic infection is Asf1a dependent. J Virol. 2012;86:12313–12321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01570-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzalli MH, Conwell SE, Berrios C, DeCaprio JA, Knipe DM. Nuclear interferon-inducible protein 16 promotes silencing of herpesviral and transfected DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4492–4501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316194110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang J, Shi Y, Valin A, Xuan Y, Gill G. Direct binding of CoREST1 to SUMO-2/3 contributes to gene-specific repression by the LSD1/CoREST1/HDAC complex. Mol Cell. 2009;34:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placek BJ, Huang J, Kent JR, Dorsey J, Rice L, Fraser NW, Berger SL. The histone variant H3.3 regulates gene expression during lytic infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2009;83:1416–1421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U, Lallemand-Breitenbach V, de The H. PML nuclear bodies: regulation, function and therapeutic perspectives. The Journal of pathology. 2014;234:289–291. doi: 10.1002/path.4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz DC, Ayyanathan K, Negorev D, Maul GG, Rauscher FJ., 3rd SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 2002;16:919–932. doi: 10.1101/gad.973302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz DC, Friedman JR, Rauscher FJ., 3rd Targeting histone deacetylase complexes via KRAB-zinc finger proteins: the PHD and bromodomains of KAP-1 form a cooperative unit that recruits a novel isoform of the Mi-2alpha subunit of NuRD. Genes Dev. 2001;15:428–443. doi: 10.1101/gad.869501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YJ, Matson C, Lan F, Iwase S, Baba T, Shi Y. Regulation of LSD1 histone demethylase activity by its associated factors. Mol Cell. 2005;19:857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa K, Chavez L, Hakre S, Calvanese V, Verdin E. Reactivation of latent HIV by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva L, Cliffe A, Chang L, Knipe DM. Role for A-type lamins in herpesviral DNA targeting and heterochromatin modulation. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000071. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel JL, Kristie TM. The dynamics of HCF-1 modulation of herpes simplex virus chromatin during initiation of infection. Viruses. 2013;5:1272–1291. doi: 10.3390/v5051272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QY, Zhou C, Johnson KE, Colgrove RC, Coen DM, Knipe DM. Herpesviral latency-associated transcript gene promotes assembly of heterochromatin on viral lytic-gene promoters in latent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16055–16059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505850102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlow Z, Kristie TM. Recruitment of the transcriptional coactivator HCF-1 to viral immediate-early promoters during initiation of reactivation from latency of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2009;83:9591–9595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01115-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Greschik H, Fodor BD, Jenuwein T, Vogler C, Schneider R, Gunther T, Buettner R, Metzger E, Schule R. Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:347–353. doi: 10.1038/ncb1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka J, Myers MP, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Herr W. Human Sin3 deacetylase and trithorax-related Set1/Ash2 histone H3-K4 methyltransferase are tethered together selectively by the cell-proliferation factor HCF-1. Genes Dev. 2003;17:896–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.252103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]