Abstract

Patients with refractory epilepsy undergo video electroencephalography for seizure characterization; among whom approximately 10–30% will be discharged with the diagnosis of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). Clinical PNES predictors have been described, but in general are not sensitive or specific. We evaluated whether multiple complaints in routine review of system (ROS) questionnaire could serve as a sensitive and specific marker of PNES. We performed a retrospective analysis of standardized ROS questionnaire completed by patients with definite PNES and epileptic seizures (ES) diagnosed in our adult epilepsy monitoring unit. A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to determine whether PNES and ES groups differed with respect to the percentage of complaints on ROS. Ten-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate the predictive error of a logistic regression classifier for PNES status based on percentage of positive complaints on ROS. A total of 44 patients were included for analysis. Patients with PNES had a significantly higher number of complaints on the ROS questionnaire compared to patients with epilepsy. A threshold of 17% positive complaints achieved a 78% specificity and 85% sensitivity for discriminating between PNES and ES. We conclude that routine ROS questionnaire may be a sensitive and specific predictive tool for discriminating between PNES and ES.

Keywords: Epilepsy, seizure, psychogenic non-epileptic, review of systems

1. INTRODUCTION

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) represent an important subset of apparently pharmaco-resistant epilepsy. PNES is often misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures (ES) in the community leading to unnecessary, and potentially harmful, treatment in the form of inappropriate use of antiepileptic medications, invasive procedures during prolonged seizures, and the economic burden of frequent hospital admissions [1]. One-third of the patients with PNES will have ‘prolonged status’, and up to three quarters of these cases may be recurrent, leading to unnecessary treatment and sometimes death [2,3]. It has been calculated that, on average, PNES diagnosis is delayed by approximately seven years [4].

The distinction of PNES from ES is sometimes difficult even for the experienced clinician. Certain clinical and demographic characteristics have been described that increase the likelihood for PNES including female gender, psychiatric history, history of abuse, prolonged spells, non-stereotyped movements, eye fluttering, preserved awareness, and episodes triggered by observers[5–7]. Ictal stuttering is a specific, but not sensitive, marker of PNES [8]. However, the diagnosis of PNES is still often difficult to make, and it accounts for 10–30% of the admissions to the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) [2,5]. Conversely, up to 20% of the patients referred for video electro-encephalography (VEEG) with a diagnosis of PNES may have ES or physiologic non-epileptic events [9].

Functional somatic comorbidities are more common in patients with diagnosis of PNES than with epilepsy [10]. We observed that patients clinically suspected to have PNES tend to report more somatic complaints in our review of systems (ROS) questionnaire. Hence, we systematically analyzed whether documenting multiple complaints in the ROS questionnaire would aid in the diagnosis of PNES. We retrospectively analyzed the ROS questionnaire of patients ultimately diagnosed with PNES in the EMU, and compared them to patients diagnosed with ES, to determine the discriminant value of the routinely administered questionnaire.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients admitted to the Baylor Comprehensive Epilepsy Center EMU from January 2011 through May 2014. Patients with a definite diagnosis of PNES or ES were included. We excluded patients with mixed PNES and ES, physiologic non-epileptic events, and patients with inconclusive diagnosis due to failure of capturing a ‘typical event’. Additionally, patients with a history of intellectual disability were excluded. All included patients had a self-reported ROS questionnaire in their electronic charts. The majority of patients responded to the ROS questionnaire during their initial epilepsy clinic visit, or during their initial Neurosurgical evaluation. The study was approved by Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

2.2. ROS questionnaire

There were four different ROS questionnaire formats (presented as supplementary material). These questionnaires were given to the patients in the clinic per availability accounting for this variability. One questionnaire format included a continuous list of symptoms, and the remainder included a list of symptoms subdivided by system. Overall the total number of symptoms available for selection ranged from 41 to 79 items, with the exception of one questionnaire that was of 29 items. One questionnaire format appeared to have two versions containing 61 or 64 questions.

The ROS questionnaires were analyzed in patients with PNES and ES. Each item answered positively was given a score of one across the different questionnaires. To account for the differences in the number of items between the questionnaires, the positive responses were summarized as a percentage of the total number of items in the questionnaire. The different questionnaires used are given as supplementary material.

2.3. Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.1.0.

Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to compare PNES and ES groups with respect to percentage of positive complaints. To control for potential confounding effects of baseline characteristics, the following were included as covariates: gender, age at evaluation, age at epilepsy onset, psychiatric history, and a history of abuse. Quantile-quantile plots and histograms were used to evaluate the need for transformations. Observations located outside 1.5 times the interquartile range of the quartiles were considered outliers. A square-root transformation was performed on percentage data to eliminate right-skewness.

Ten-fold cross-validation was used to assess the ability of a discriminant function based on the percentage of positive complaints on ROS to predict PNES diagnosis. Due to non-normality of percentage data, logistic regression was used for classification [11]. To measure general classification performance, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed by calculating sensitivity and specificity over various cutoff levels. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was then calculated as a general measure of performance. Cutoff levels that maximized the Youden index were used to identify the percentage of positive complaints on ROS that best predicted PNES/epilepsy classification.

3. RESULTS

Among the 342 patients admitted to the EMU during the time period of the study, 298 patients were excluded due to incomplete chart information or exclusion criteria noted above. Of the 44 patients included, 21 had PNES and 23 had ES. Baseline characteristics of these patient groups are shown in Table 1. PNES and ES groups were similar with respect to gender, age at evaluation, self-reported psychiatric history, and history of abuse. Compared to the ES group, the PNES group had a significantly later age of epilepsy onset.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and comparison of percentage of positive complaints on ROS for patients with ES and PNES. ES, epileptic seizures; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, ROS, review of systems; SD, standard deviation.

| ES (n=23) | PNES (n=21) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male) a | 10 | 6 | 0.36 |

| Age at evaluation (years, mean±SD) b | 43.2±14.1 | 38.8±11.8 | 0.32 |

| Age of epilepsy onset (years, mean±SD) b | 20.7±17.7 | 33.1±13.4 | 0.005* |

| Psychiatric disorder a | 4 | 9 | 0.10 |

| History of abuse a | 1 | 2 | 0.60 |

| Percentage of positive complaints on ROS questionnaire | |||

| Mean(±SD) | 11.15±14.22 | 36.96±18.00 | |

| Range | 0.00–49.20 | 9.80–70.70 | |

Fisher’s exact test

Mann-Whitney U test

Significant difference at the 0.05 level

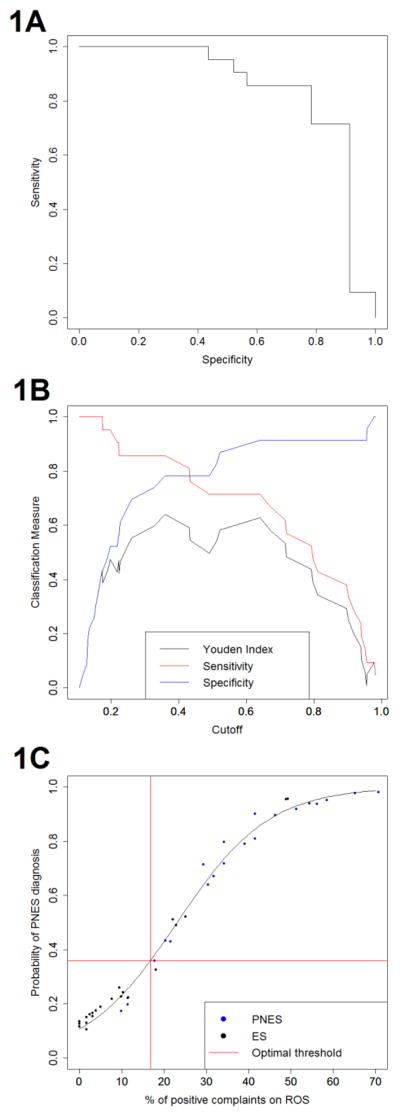

Table 1 includes a comparison of the percentage of positive complaints on ROS for the PNES and ES groups. From MANCOVA, PNES patients were found to have a larger percentage of positive complaints on ROS than epilepsy patients (F=20.78, p<0.0001). Typical completed ROS forms are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Figure 1a compares the sensitivity and specificity of percentage of positive complaints on ROS for predicting PNES/epilepsy classification. This corresponded to an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.845, indicating excellent discrimination [12]. Figure 1b shows the estimated sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index at various cutoff thresholds. The Youden index was maximized at a threshold of 36.0%, which corresponded classifying subjects as PNES if greater than 17% of positive complaints on ROS, and classifying as epilepsy otherwise (Supplementary Table 1, Figure 1c). Use of this threshold yielded a specificity of 78.3% and sensitivity of 85.7%.

Figure 1.

Plots showing the utility of ROS for diagnosing PNES and ES: 1a. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for classification performance based on percentage of complaints on ROC. 1b. Sensitivity, specificity and Youden Index at various cutoff thresholds. 1c. Optimal threshold for PNES diagnosis based on percentage of positive complaints on ROS.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that patients with PNES have a higher number of complaints on routine review of systems questionnaire compared to patients with epilepsy. With a cutoff of 17% of the ROS items reported as positive, there is 78.3% specificity and 85.7% sensitivity of the diagnosis being PNES, with higher specificity of diagnosis at higher cutoffs. The likely explanation for the greater number of ROS symptoms in patients with PNES is related to its classification as a somatoform or a conversion disorder [2,13]. Although the underlying psychopathology of PNES remains to be fully characterized, this may lead to the PNES patients to have more ‘somatic complaints’ than patients with ES. This is also supported by previous reports of PNES patients having higher scores in somatization questionnaires compared to epilepsy patients which may also correlate with overall outcome [14]. Patients who have diagnosis of chronic pain and fibromyalgia as well as those who experience a “seizure” during a clinic visit are also more likely to have PNES [15].

In clinical practice, a standardized ROS questionnaire may be used as a simple PNES predictive tool during the initial clinic visit, or as a screening tool for patients referred to the monitoring unit. While many clinicians informally use such measures in estimating the likelihood that a given patient may have ES or NES, our study systematically analyses this, and provides a statistical basis for such inferences. We also provide a cut-off where a given subject is more likely to have ES or NES based on our questionnaires. In addition, a positive ROS questionnaire coupled with clinical markers suggestive of PNES may be particularly useful in geographic areas where EMU services are not readily available. Evaluation at specialized epilepsy centers of refractory epilepsy remains delayed: on average, patients with refractory epilepsy presented 23 years after onset, and PNES patients five years after onset, of their symptoms[16]. Treatment delay may lead to increased morbidity and mortality in both groups. Furthermore, the longer duration of misdiagnosis in PNES has been correlated with worse prognosis [13].

In our analysis, we found that the PNES group had a significantly later age of onset than the ES group, as has been previously reported. No differences were found with respect to gender, psychiatric history or history of abuse unlike previous reports. Possible explanations for this discrepancy may be the small sample size, and incomplete self-report of psychiatric and history of abuse in our retrospective analysis.

Limitations and future directions

We acknowledge the limitations of our study, including the retrospective nature and the small sample size of 44 patients. Although our preliminary results appear promising, caution is advised in interpreting these results until a larger study, ideally prospective in nature, is performed in order to obtain a separate validation dataset. Nevertheless, our strongly positive findings argue that, in the appropriate clinical setting, multiple complaints in the ROS may be used as another predictive tool for PNES. A limitation that can be addressed by future prospective studies is that the questionnaires applied to the patients were not identical across the groups, although of similar characteristics.

Conclusions

The differential diagnosis of PNES and ES is sometimes challenging. Up to one-third of the patients referred to epilepsy centers may have diagnosis of PNES [2,5]. Early diagnosis is crucial to avoid the risks of unnecessary treatment and delay in psychiatric intervention that may benefit some patients [3,4]. Sensitive and specific clinical predictors would facilitate the diagnosis of PNES early in its course. While video EEG remains the “gold standard” for making the diagnosis of PNES by capturing the “typical spells”, our results demonstrate that multiple somatic complaints in a standard review of system questionnaire exhibits great sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of PNES, and may be a useful aid in developing a pretest probability for its diagnosis during evaluation of seizures.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) represent an important subset of apparently pharmaco-resistant epilepsy.

The diagnosis of PNES is still often difficult to make, and it accounts for 10–30% of the admissions to the epilepsy monitoring unit.

We observed that patients clinically suspected to have PNES tend to report more somatic complaints in our review of systems (ROS) questionnaire.

We retrospectively analyzed the ROS questionnaire of patients ultimately diagnosed with PNES in the EMU, and compared them to patients diagnosed with ES, to determine the discriminant value of the routinely administered questionnaire.

PNES patients have a higher number of complaints on routine review of systems questionnaire compared to patients with epilepsy. A cutoff of 17% of the ROS items reported as positive, there is 78.3% specificity and 85.7% sensitivity of the diagnosis being PNES, with higher specificity of diagnosis at higher cutoffs.

Acknowledgments

Support for this publication was provided by the National Library of Medicine Training Fellowship in Biomedical Informatics, Gulf Coast Consortia for Quantitative Biomedical Sciences (Grant #2T15LM007093-21) (SC); The National Institute of Health (Grant #5T32CA096520-07) (SC); Epilepsy Foundation of America (Research Grants Program) (ZH); the Baylor College of Medicine Computational and Integrative Biomedical Research (CIBR) Center Seed Grant Awards (ZH); and the Baylor College of Medicine Junior Faculty Seed grants (ZH).

ABBREVIATIONS

- PNES

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures

- ES

Epileptic seizures

- EMU

Epilepsy monitoring unit

- VEEG

Video electro-encephalography

- ROS

Review of systems

- MANCOVA

Multivariate analysis of covariance

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

Footnotes

6. DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

None of the authors has any conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brown RJ, Syed TU, Benbadis S, LaFrance WC, Reuber M. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reuber M, Elger CE. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: review and update. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:205–16. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(03)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuber M, Baker GA, Gill R, Smith DF, Chadwick DW. Failure to recognize psychogenic nonepileptic seizures may cause death. Neurology. 2004;62:834–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113755.11398.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuber M, Fernández G, Bauer J, Helmstaedter C, Elger CE. Diagnostic delay in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 2002;58:493–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodde NMG, Brooks JL, Baker GA, Boon PaJM, Hendriksen JGM, Aldenkamp AP. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures--diagnostic issues: a critical review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cragar DE, Berry DTR, Fakhoury TA, Cibula JE, Schmitt FA. A review of diagnostic techniques in the differential diagnosis of epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Neuropsychol Rev. 2002;12:31–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1015491123070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syed TU, LaFrance WC, Kahriman ES, Hasan SN, Rajasekaran V, Gulati D, et al. Can semiology predict psychogenic nonepileptic seizures? A prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:997–1004. doi: 10.1002/ana.22345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoerth MT, Wellik KE, Demaerschalk BM, Drazkowski JF, Noe KH, Sirven JI, et al. Clinical predictors of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a critically appraised topic. Neurologist. 2008;14:266–70. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31817acee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parra J, Iriarte J, Kanner AM. Are we overusing the diagnosis of psychogenic non-epileptic events? Seizure. 1999;8:223–7. doi: 10.1053/seiz.1999.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixit R, Popescu A, Bagić A, Ghearing G, Hendrickson R. Medical comorbidities in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic spells (PNES) referred for video-EEG monitoring. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;28:137–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press J, Wilson S. Choosing between logistic regression and discriminant analysis. 1978;73:699–705. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. Assessing the Fit of the Model; pp. 143–202. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benbadis SR. The problem of psychogenic symptoms: is the psychiatric community in denial? Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reuber M, House AO, Pukrop R, Bauer J, Elger CE. Somatization, dissociation and general psychopathology in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2003;57:159–67. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benbadis SR. A spell in the epilepsy clinic and a history of “chronic pain” or “fibromyalgia” independently predict a diagnosis of psychogenic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:264–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haneef Z, Stern J, Dewar S, Engel J. Referral pattern for epilepsy surgery after evidence-based recommendations: a retrospective study. Neurology. 2010;75:699–704. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.