Abstract

Background

Cardiac dysfunction has been reported to occur in as much as 42% of adults with brain death, and may limit cardiac donation after brain death. Knowledge of the prevalence and natural course of cardiac dysfunction after brain death may help to improve screening and transplant practices but adequately sized studies in pediatric brain death are lacking. The aims of our study are to describe the prevalence and course of cardiac dysfunction after pediatric brain death.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using an organ procurement organization database (Life Center Northwest) of potential pediatric cardiac donors diagnosed with brain death between January 2011 and November 2013. Transthoracic echocardiograms (TTEs) were reviewed for cardiac dysfunction [defined as ejection fraction (EF) < 50% or the presence of regional wall motion abnormalities (RWMAs)]. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze clinical characteristics and describe longitudinal echocardiogram findings in a subgroup of patients. We examined for heterogeneity between cardiac dysfunction with respect to cause of brain death.

Results

We identified 60 potential pediatric cardiac donors (age ≤ 18 years) with at least one TTE following brain death. Cardiac dysfunction was present in 23 (38%) patients with brain death. Mean EF (37.6% vs. 62.2%) and proportion of procured hearts (56.5% vs. 83.8%) differed significantly between the groups with and without cardiac dysfunction, respectively. Of the 11 subjects with serial TTE data, the majority (73%) of patients with cardiac dysfunction improved over time, leading to organ procurement. No heterogeneity between cardiac dysfunction and particular causes of brain death was observed.

Conclusion

The frequency of cardiac dysfunction in children with brain death is high. Serial TTEs in patients with cardiac dysfunction showed improvement of cardiac function in most patients, suggesting that initial decisions to procure should not solely depend on the initial TTE exam results.

Keywords: Cardiac dysfunction, Children, Brian death, Organ donation, Transplantation, Echocardiography

Background

The lack of adequate donor hearts for transplantation is a significant worldwide problem, with many pediatric heart transplant candidates dying while on the waiting list1. While the primary source of donor hearts for transplantation comes from patients with brain death, cardiac dysfunction has been reported to occur in as much as 42% of adults with brain death2, and may limit cardiac donation after brain death. This may account for approximately 26% of unused hearts, which could ultimately be used if cardiac dysfunction is transient and/or resolves over time3.

While the prevalence of cardiac dysfunction after adult brain death is high4, studies have shown that cardiac dysfunction is sometimes reversible after optimization of hemodynamic parameters before organ procurement5 with no compromised outcome of organ recipients6. While a greater knowledge of cardiac dysfunction after brain death in the adult population has been gained over the last decade, investigations in the pediatric population have been limited to small case series7. The aims of our study were to determine the prevalence and course of cardiac dysfunction, as well as to examine organ procurement practices after pediatric brain death of differing etiologies.

Methods

Donors

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from Life Center Northwest (LFNW), an organ procurement organization for a 4-state region (Alaska, Montana, North Idaho, and Washington). Because the entire study population carried a diagnosis of brain death, IRB was waived. We identified all potential donors with age < 18 years that were being considered for cardiac donation after brain death between January 2011 and November 2013, all of whom received at least one screening transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). We excluded 4 donors because they each had a pre-brain death TTE, but did not have a TTE after brain death was declared. Data were abstracted on donor demographics, hemodynamic parameters, use of vasopressors, cause of brain death, as well as whether the donor was felt to be a suitable candidate for cardiac donation (either procured or planned procurement that was not carried out due to the lack of a suitable recipient). Hemodynamic parameters were age adapted, as reported elsewhere8. In addition, echocardiography data was collected, including serial echocardiograms as available.

Clinical care

During the study period, clinical care was delivered per local standard institutional practices. The diagnosis of brain death was made, and death was declared. By the conclusion of that process, patients were referred for evaluation to LCNW. After authorization for donation was confirmed, management was transferred to the LCNW team. Subsequent protocol-based donor management was targeted towards optimizing hemodynamic stability cardiopulmonary function, and electrolyte status as shown in Table 3. Age-appropriate blood pressure was supported with vasopressors, inotropes and/or thyroid hormone infusion, as required. Pulmonary management was adjusted to avoid pressure or volume insults while targeting PaO2/FiO2 ratios above 300, utilizing chest physiotherapy, recruitment maneuvers and diuresis. Fluid and electrolyte targets included correction of hypovolemia, a urine output of greater than 0.5 ml/kg/hour, and a serum sodium goal of less than 150 mEq/L utilizing fluid boluses, enteral free water, and vasopressin. Based on the organ donor management protocol (Table 3), a LCNW attending physician provided oversight and direction to maintain hemodynamic goals as tolerated (without significant management changes) until the time of organ procurement.

Table 3.

Organ Donor Management Protocol*

| Category | Goal |

|---|---|

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | Neonate: 40–60 Infant: 60–75 Toddler: 65–80 Preschool: 65–85 Child: 70–90 Adolescent: 75–95 |

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | 4–12 (lung donor <8 and ideally <6) |

| Arterial blood gas – pH | 7.30 – 7.50 |

| Lactate (mg/dL) | < 2.0 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 135 – 150 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 80 – 140 |

| Urine output | ≥ 1–2 ml/kg/hr balance over 4 hours |

| Temperature (C) | 36 – 37.5 degrees |

| Hematocrit (%) | > 27 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | ≥ 300 |

| Hormone replacement therapy |

T4: 0.7 mcg/kg bolus, infusion titrated from 1 mcg/hr – 3 mcg/hr (max) Methylprednisolone: 30 mg/kg bolus (one dose) Vasopressin (for diabetes insipidus) 0.5–1 mU/kg/hr – titrated to 10 mU/kg/hr (max) Insulin: 0.05–0.1 U/kg/hr – titrated to maintain glucose 80–140 mg/dL |

| Vasopressor doses (titrated to hemodynamic goals above) |

T4: see protocol above Vasopressin**: 0.3–2 mU/kg/min Dopamine: 2–20 mcg/kg/min Epinephrine: 0.05–1 mcg/kg/min Norepinephrine: 0.05–2 mcg/kg/min Phenylephrine: 0.1–0.5 mcg/kg/min Dobutamine: 2–20 mcg/kg/min Milrinone: 0.25–0.5 mcg/kg/min |

Adapted from LFNW pediatric donor management guidelines

Different from diabetes insipidus dose

Evaluation of cardiac dysfunction

All echocardiography data was collected using the TTE approach, including serial echocardiograms in select donors with initially poor cardiac function or donors with worsening hemodynamic parameters; and all TTE data were interpreted by the treating cardiologist. For this study, echocardiogram reports were reviewed, and ejection fraction (EF), regional wall motion abnormalities (RWMA), and any other significant findings were abstracted. Cardiac function of the donor was dichotomized into 2 categories: normal or cardiac dysfunction (defined as EF < 50% or presence of one or more RWMAs). In addition, in donors with serial TTEs, similar data were abstracted, with the addition of TTE time course.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to report clinical characteristics, EF, and organ procurement practices of donors with and without cardiac dysfunction. Furthermore, details of longitudinal echocardiogram findings in a subgroup of patients with serial TTEs are reported. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables or as counts and percentages for categorical variables. The Student’s t-test was used to examine differences between normally distributed continuous variables. The Chi-Squared test was used to test for differences between proportions of categorical variables, and a Fisher’s Exact test was used when needed for data representing variables with low frequencies. The Chi-Squared test was used to test for heterogeneity between cardiac dysfunction and particular cause of brain death. Statistical analysis was performed with STATA Version 13 (College Station, Texas).

Results

Clinical characteristics

During the study period, there were 64 pediatric donors (age ≤ 18 years) with at least one TTE report following brain death. We excluded 4 possible donors due to missing or incomplete TTE reports, leaving a total of 60 patients for the analysis. In 11 (18.3%) patients, serial TTEs were performed due to monitoring for improvement of cardiac function or hemodynamic deterioration (at LFNW attending physician discretion). Among 44 donors with data on heart rhythm available, 23 (52.3%) donors had episodes of sinus tachycardia and 1 (2.3%) had an episode of supraventricular tachycardia. Clinical characteristics comparing potential donors with and without cardiac dysfunction on the first TTE after brain death diagnosis are described in Table 1. Comparing the group with and without cardiac dysfunction, there was no significant difference in mean age (118.3 ± 75.9 months vs. 96.8 ± 83.1 months, p=0.67) or need for vasopressors (86.7% vs. 75.5%, p=0.47). Among the 48 donors requiring vasopressors, vasopressin was most commonly used [34/48 (70.8%)], followed by levothyroxine [30/48 (62.5%)], norepinephrine [11/48 (22.9%)], dopamine [10/48 (20.8%)], epinephrine [6/48 (12.5%)], phenylephrine [4/48 (8.3%)], and dobutamine [1/48 (2.1%)]. The mean time from the diagnosis of brain death to the first echocardiogram for both groups was 30.5±8.3 hours.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population (stratified by the presence or absence of cardiac dysfunction). Data presented as means (± SD) and proportions for continuous and categorical data, respectively.

| Cardiac Dysfunction (n=23) |

No Cardiac Dysfunction (n=37) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 118.3 ± 75.9 | 96.8 ± 83.1 | 0.67 |

| Receiving vasopressors, n(%) | 20 (86.7%) | 28 (75.5%) | 0.47 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 37.6 ± 12.2 | 62.2 ± 5.3 | <.0001 |

| Heart procured for transplantation, n(%) | 13 (56.5%) | 31 (83.8%) | 0.02 |

| Cause of Brain Death, n(%): | 0.50 | ||

| Traumatic brain injury | 11 (47.8%) | 15 (40.5%) | |

| Anoxia | 10 (43.5%) | 21 (56.8%) | |

| Stroke | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (2.7%) | |

P-values calculated from t-test and chi-squared analysis for continuous and categorical data, respectively.

Echocardiography findings and organ procurement practices

Table 1 describes TTE findings in donors with and without cardiac dysfunction. Cardiac dysfunction was present in 23 (38%) of possible donors. The mean EF in the group with cardiac dysfunction was lower than the group with normal cardiac function (37.6% ± 12.2 vs. 62.2% ± 5.3; p<.0001). The proportion of procured hearts was lower in the group with cardiac dysfunction (56.5% vs. 83.8%, p=0.02).

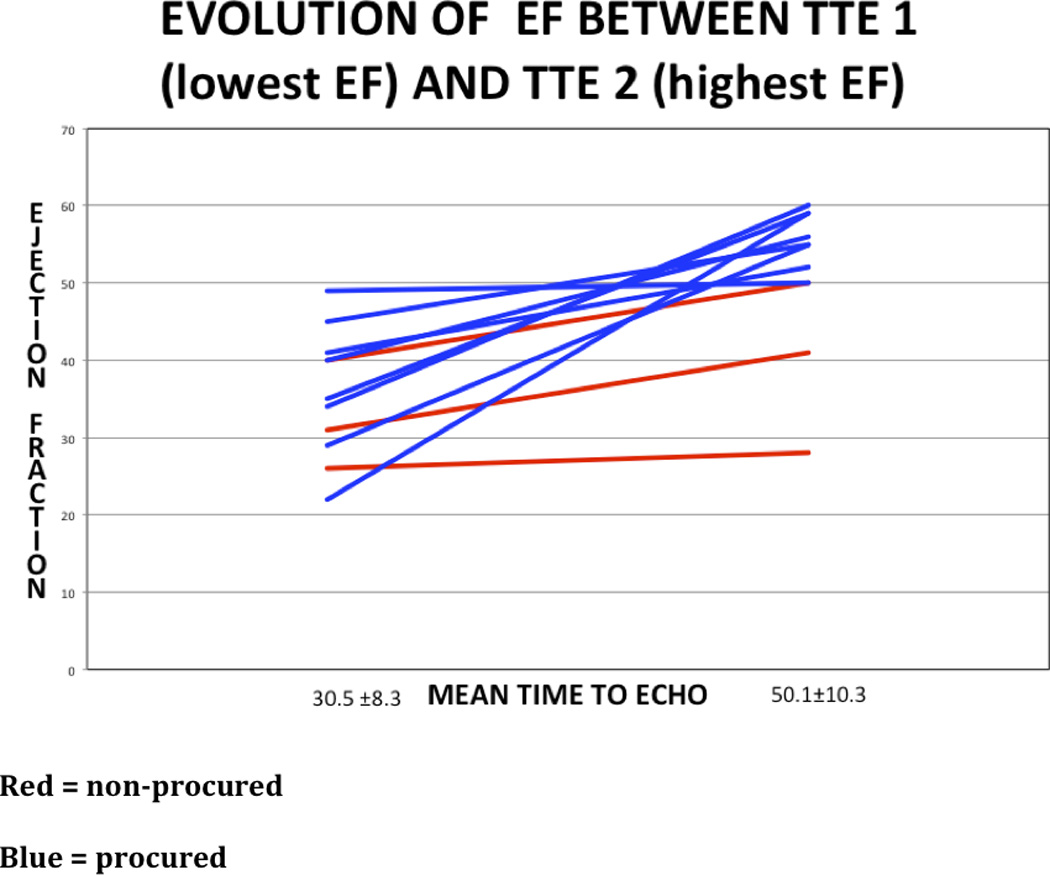

Table 2 examines longitudinal TTE findings in the subgroup of patients who received serial echocardiograms (n=11). Two to four serial TTE were performed in each of these patients, and the time difference between brain death and TTE was recorded. The mean lowest EF in each donor was 35.6 ± 8.2% and increased to a mean EF 51.4 ± 9.5%. Three (27.3%) donors showed a decrease in EF after an initial TTE with normal EF, and 9 (82.0%) donors showed an increase of LVEF ≥ 50% by their final TTE. Eight (89.0%) of these nine hearts were transplanted, with one heart (subject #3) not procured for transplant (only recovered for heart valves) due to persistence of RWMAs. The remaining 2 donors without improvement in cardiac function did not have their hearts procured for transplantation. Figure 1 describes the evolution of EF in these subjects.

TABLE 2.

Serial transthoracic echocardiograms and organ procurement practices in a subset of patients with low ejection fraction (EF) or hemodynamic decompensation

| Patient | Age (y) | EF (%) | EF 2 (%) | EF 3 (%) | EF 4 (%) | BD to TTE 1 (h) |

BD to TTE 2 (h) |

BD to TTE 3 (h) |

BD to TTE 4 (h) |

procured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 26 | 28 | 24 | 59 | no | ||||

| 2 | 16 | 31 | 41 | 26 | 46 | no | ||||

| 3 | 14 | 40 | 50 | 18 | 29 | no | ||||

| 4 | 18 | 45 | 55 | 32 | 42 | yes | ||||

| 5 | 6 | 49 | 50 | 44 | 62 | yes | ||||

| 6 | 1.2 | 40 | 56 | 28 | 44 | yes | ||||

| 7 | 15 | 22 | 36 | 59 | 24 | 35 | 48 | yes | ||

| 8 | 4 | 41 | 46 | 52 | 24 | 42 | 51 | yes | ||

| 9 | 15 | 65 | 29 | 55 | 28 | 44 | 63 | yes | ||

| 10 | 16 | 61 | 35 | 59 | 14 | 35 | 50 | yes | ||

| 11 | 2 | 65 | 34 | 55 | 60 | 10 | 27 | 50 | 58 | yes |

Figure 1.

Ejection fraction (%) versus time (hours) in the donor subgroup with serial TTEs (n=11).

Relationship between injury type and cardiac dysfunction

Groups with and without cardiac dysfunction were comparable with respect to causes of brain death. Type of injury was examined as possibly being associated with cardiac dysfunction after brain death. As the pathophysiology of cardiac dysfunction may be different after anoxic injury compared to traumatic brain injury (TBI), we compared the prevalence of cardiac dysfunction in anoxic injury [10/31 subjects – 32.3%] and TBI [11/26 – 42.3%], and we found no statistically significant difference (p=0.43). Furthermore, as shown in Table 1, no heterogeneity was observed between any injury type and the subsequent development of cardiac dysfunction after a diagnosis of brain death (Chi-squared test for heterogeneity 2.38, p=0.50).

Discussion

Overall, the results of our study suggest that cardiac dysfunction is common after pediatric brain death, it is reversible in the majority of cases, and the presence of initially documented cardiac dysfunction has an influence on organ procurement practices. Furthermore, no single cause of brain death was more likely to be associated with cardiac dysfunction than another. While cardiac dysfunction after pediatric brain death has been described in small case series, to our knowledge, our study is the largest so far to describe the course of cardiac dysfunction in the pediatric donor population.

The prevalence of cardiac dysfunction in our study is in the same range as described in previous adult populations2, 3, but below the prevalence described in a smaller study of pediatric brain death in 23 potential donors, which reported a figure of 57%7. Similar to our study, prior studies2, 7 were also unable to show an association between cause of brain death and cardiac dysfunction in adult and mixed populations, suggesting that brain death itself may represent a final common underlying pathophysiologic pathway to cardiac dysfunction.

An insight into the pathophysiology of cardiac dysfunction after a variety of brain injuries has been gained over the past several decades, however detailed mechanistic information regarding brain-death induced cardiac dysfunction is less clear. The prevailing theory involves a catecholamine-induced effect, likely secondary to ischemia, elevated intracranial pressure, and damage to the insular cortex and hypothalamus9. This results in a “catecholamine storm” which is clinically manifested by tachycardia, increased vascular resistance, and potentially cardiac dysfunction10. Ultimately, this process leads to injury to the myocardium secondary to both global and local catecholamine release11, and is aggravated by dysregulated endocrine function and neuroinflammation12. Myocardial specimens after brain injury have consistently shown pathologic findings of contraction-band necrosis (CBN), which is the hallmark lesion of myocardial injury secondary to catecholamine excess9. After the acute phase, both cardiac dysfunction and downregulation of sympathetic tone may lead to hypotension and decreased organ perfusion, which includes the heart13. Furthermore, a similar underlying pathophysiologic mechanism may also account of the phenomenon of neurogenic pulmonary edema14, which may account for the increase in extravascular lung water which is commonly noted after brain death15.

Cardiac dysfunction has been well described in other neurologic and psychiatric paradigms including subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)16, traumatic brain injury17, and acute emotional stress18. Hravnak et al showed that cardiac dysfunction is common after aneurysmal SAH; although reversibility was documented, some abnormalities continued to persist as late as 12 days after the initial neurologic injury in the majority of those with cardiac dysfunction19. Wittstein et al described cardiac dysfunction after acute emotional stressors and demonstrated both elevated catecholamine concentrations and CBN in a group of patients that underwent myocardial biopsy – furthermore, cardiac dysfunction was fully reversible in all of the patients in the study within two to four weeks after the initial presentation18. The mechanism of cardiac dysfunction after brain death is more poorly understood, as likely several pre-brain death factors play a role, including the intensity of brain injury, rate of rise of intracranial pressure, and the time from injury to brain death. Furthermore, the particular cause of brain death (i.e. anoxia versus TBI) may, in fact, have different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms that ultimately lead to the clinical findings of cardiac dysfunction.

In the setting of heart donation, the most common cause for exclusion of cardiac procurement is a history of heart disease and myocardial dysfunction, the latter probably associated with brain death20. Similar to other paradigms of neurologic injury, evidence in brain death-induced cardiac dysfunction also shows that may hearts can recover normal function over time both in the donor and after transplantation into a recipient6. In the UNOS consensus recommendations to improve the yield of donor evaluation5, serial TTE monitoring after hemodynamic optimization and stabilization of the donor is recommended. This has been confirmed in adult populations, where studies have shown increased organ procurement after using this approach to donor management and monitoring21–23; however, the data in the pediatric literature is less robust. Boucek et al showed that survival rate and graft function on TTE was similar when comparing transplantation of dysfunctional and normal hearts in the pediatric population, demonstrating that pediatric donor hearts with cardiac dysfunction can be procured and transplanted successfully24. In our study 11 pediatric patients with cardiac dysfunction had serial TTEs; 9 of the 11 donors showed an increase in EF, and 8 of the 11 (72%) donors were ultimately transplanted. Thus, further resuscitation of organ donors, maintenance of hemodynamic goals, and simply giving more time for cardiac improvement with continued observation beyond 36–48 hours with serial TTE may provide for the availability of more donor hearts.

There are some limitations in our study. First, the cohort consisted of only potential cardiac donors, making generalizability to other brain dead pediatric organ donor populations less clear. However, relatively few pediatric donor hearts are not evaluated by TTE. Second, the lack of standardization of time to echocardiogram performance after brain death leaves the precise course of cardiac dysfunction unclear. Third, the cross-sectional nature of our study made it difficult to ascertain the true direction of the causal pathway between brain death and cardiac dysfunction, and cannot completely rule out the possibility of reverse causality (i.e. cardiac dysfunction leading to brain death). In this circumstance however, it would be less likely that the heart be considered and therefore evaluated with echocardiography. Fourth, because of the lack of detailed information about the pre-brain death phase of care (the inherent limitation of most organ donation registries), it is impossible to make a strong inference regarding the underlying mechanism and pathophysiology of brain death-induced cardiac dysfunction. Lastly, detailed information about cardiac history was lacking, leaving open the possibility of confounding the association between pediatric brain death and cardiac dysfunction. However, it is unlikely that children had pre-existing cardiac disease before their neurologic injury. Despite the study limitations, our study provides new information on the prevalence, TTE utilization and time course of cardiac dysfunction in pediatric brain death.

Conclusion

The prevalence and time course of cardiac dysfunction after pediatric brain death strongly suggests that a more formal approach should be adopted to evaluation and monitoring of cardiac function. Serial TTEs in patients with cardiac dysfunction showed improvement of cardiac function in the majority of patients, ultimately leading to organ procurement for transplantation, which would not have happened if decision-making were dependent on the initial TTE exam. Finally, this study argues for a common pathway between the brain and heart in neurological diseases, thereby, warranting future studies that explore the mechanisms that underlie this complex relationship.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the management and staff of Life Center Northwest for their help and support in gathering clinical records, databases, and materials for our analysis.

This study was supported, in part, by an NRSA T32 (T32 GM086270) training grant.

Footnotes

Institution where work was performed: University of Washington, Seattle, WA

References

- 1.Smits JM, Thul J, De Pauw M, et al. Pediatric heart allocation and transplantation in Eurotransplant. Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2014 doi: 10.1111/tri.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dujardin KS, McCully RB, Wijdicks EF, et al. Myocardial dysfunction associated with brain death: clinical, echocardiographic, and pathologic features. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2001;20:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaroff JG, Babcock WD, Shiboski SC. The impact of left ventricular dysfunction on cardiac donor transplant rates. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2003;22:334–337. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallardo A, Anguita M, Franco M, et al. [The echocardiographic findings in patients with brain death. The implications for their selection as heart transplant donors] Revista espanola de cardiologia. 1994;47:604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaroff JG, Rosengard BR, Armstrong WF, et al. Consensus conference report: maximizing use of organs recovered from the cadaver donor: cardiac recommendations, March 28–29, 2001. Crystal City, Va. Circulation. 2002;106:836–841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025587.40373.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaroff JG, Babcock WD, Shiboski SC, Solinger LL, Rosengard BR. Temporal changes in left ventricular systolic function in heart donors: results of serial echocardiography. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2003;22:383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul JJ, Tani LY, Shaddy RE, Minich LL. Spectrum of left ventricular dysfunction in potential pediatric heart transplant donors. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2003;22:548–552. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rappaport LD, Deakyne S, Carcillo JA, McFann K, Sills MR. Age- and sex-specific normal values for shock index in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2008 for ages 8 years and older. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2013;31:838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuels MA. The brain-heart connection. Circulation. 2007;116:77–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith M. Physiologic changes during brain stem death--lessons for management of the organ donor. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2004;23:S217–S222. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banki NM, Kopelnik A, Dae MW, et al. Acute neurocardiogenic injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circulation. 2005;112:3314–3319. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apostolakis E, Parissis H, Dougenis D. Brain death and donor heart dysfunction: implications in cardiac transplantation. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2010;25:98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2008.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo G, Hackert T, Sebening C, Vahl CF, Hagl S. Modulation of coronary perfusion pressure can reverse cardiac dysfunction after brain death. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1999;67:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01307-1. discussion-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison DL, Terek M, Chawla LS. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care. 2012;16:212. doi: 10.1186/cc11226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkateswaran RV, Dronavalli V, Patchell V, et al. Measurement of extravascular lung water following human brain death: implications for lung donor assessment and transplantation. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2013;43:1227–1232. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macrea LM, Tramer MR, Walder B. Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage and serious cardiopulmonary dysfunction--a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2005;65:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prathep S, Sharma D, Hallman M, et al. Preliminary report on cardiac dysfunction after isolated traumatic brain injury. Critical care medicine. 2014;42:142–147. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hravnak M, Frangiskakis JM, Crago EA, et al. Elevated cardiac troponin I and relationship to persistence of electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:3478–3484. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamorro C, Romera MA, Silva JA. [Stunned myocardium in brain death] Medicina intensiva / Sociedad Espanola de Medicina Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias. 2006;30:299–300. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5691(06)74530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosendale JD, Kauffman HM, McBride MA, et al. Aggressive pharmacologic donor management results in more transplanted organs. Transplantation. 2003;75:482–487. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000045683.85282.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosendale JD, Kauffman HM, McBride MA, et al. Hormonal resuscitation yields more transplanted hearts, with improved early function. Transplantation. 2003;75:1336–1341. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000062839.58826.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kutsogiannis DJ, Pagliarello G, Doig C, Ross H, Shemie SD. Medical management to optimize donor organ potential: review of the literature. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2006;53:820–830. doi: 10.1007/BF03022800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boucek MM, Mathis CM, Kanakriyeh MS, et al. Donor shortage: use of the dysfunctional donor heart. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 1993;12:S186–S190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]