Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) includes pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN, NBIA1), PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN, NBIA2), neuroferritinopathy, aceruloplasminemia, and MIN-associated neurodegeneration (MPAN).1 Clinically, they can have similar presentation, with a combination of progressive extrapyramidal, cognitive, and bulbar features.1 Since genetic testing is costly and not easily accessible, MRI clues, such as the eye of the tiger sign for PKAN,2,3 are useful to guide the confirmatory genetic analyses. Herein, we describe a distinct imaging pattern of cortical iron deposition on susceptibility-weighted MRI (SWI) in genetically proven cases of neuroferritinopathy, which is not seen in genetically proven cases of PKAN or PLAN, the 2 most common forms of NBIA.

Case reports.

Case 1.

A 79-year-old woman with no significant family history had a 13-year history of slurred speech, which progressed to complete anarthria. She had swallowing problems and required a PEG tube. On examination, she had prominent craniocervical and arm dystonia, parkinsonism, and a shuffling gait. Ferritin was low (19 μg/L, normal range 30–400 μg/L).

MRI T2 fast spin echo images showed T2 hyperintensity with areas of apparent cavitation involving the globus pallidus, putamen, caudate, and cerebral peduncles bilaterally with hypointensity around their periphery. The SWI sequence showed a fine band of low signal following the contour of the cerebellar and cerebral cortex consistent with iron deposition in the cortex. This appeared as a thin line of loss of signal appearing as if traced with a black pencil. This lining was also seen in the periphery of the deep gray matter structures globus pallidus, putamen, caudate, red nuclei, substantia nigra, and dentate nuclei (figure, A.a) and around the areas of apparent cavitation. Genetic testing showed the presence of the common pathogenic mutation c.460dupA in the ferritin light chain (FTL) gene.

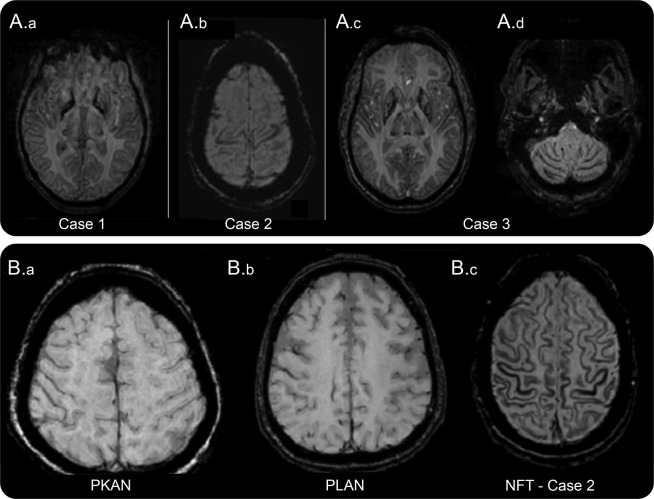

Figure. Magnetic resonance SWI in neuroferritinopathy highlighting the “pencil lining in cortex and the deep gray matter”.

(A) Magnetic resonance susceptibility weighted images (SWIs) from patients with neuroferritinopathy. (A.a) Pencil lining of cortex and deep gray matter (case 1). (A.b) Pencil lining of motor strip in cortex (case 2). (A.c) Pencil lining of cortex and deep gray matter (putamen and globus pallidus) (case 3). (A.d) Pencil lining of cerebellum (case 3). (B) Magnetic resonance SWIs. (B.a) PKAN (pantothenate kinase-associated degeneration) showing absence of pencil lining for comparison. (B.b) PLAN (PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration) showing absence of pencil lining for comparison. (B.c) Neuroferritinopathy (case 2) showing “cortical pencil lining.”

Case 2.

A 37-year-old woman with no significant family history had an 18-month history of abnormal posturing of her left arm and difficulties with speech and swallowing. On examination, she had jaw closing dystonia and upper limb dystonia, with bradykinesia on finger tapping and dystonic gait. Serum ferritin was 15 μg/L (normal range for her age 13–150 μg/L). MRI showed irregular cavitation of the globus pallidus and medial putamen bilaterally. SWI showed a band of hypointensity at the periphery of the cavities and the noncavitated putamen and caudate along with pencil lining, most conspicuous in the motor strip in the cortex (figure, A.b). Genetic testing disclosed the pathogenic duplication c.460dupA in FTL.

Case 3.

A 54-year-old man with no significant family history presented with facial grimacing and dysphagia and dysarthria of 3-year duration. On examination, he had oromandibular dystonia with blepharospasm and gait ataxia. Ferritin 14 μg/L was low (normal range 30–400 μg/L). MRI demonstrated characteristic cavitation of the globus pallidus and medial putamen bilaterally. SWI showed low signal in the periphery of the deep gray nuclei themselves (figure, A.c), at the margins of the cavities and pencil lining of the cerebral and cerebellar cortex (figure, A.c and A.d). Genetic testing showed the c.460dupA mutation in FTL.

Review of neuroimaging of normal subjects, 3 patients with genetically proven PKAN (one of these is illustrated in the figure, B.a) and 2 with PLAN (one of these is illustrated in the figure, B.b) by an experienced neuroradiologist (M.E.A.), did not reveal any cortical iron deposition on SWI. We also reviewed the literature on imaging in NBIAs and there were no reports of cortical iron deposition in PKAN, MPAN, or PLAN cases.3,4 However, cortical iron deposition was seen in 15 of 21 patients (71%) with neuroferritinopathy, and 4 patients (100%) with aceruloplasminemia, but no characteristic pattern was identified.4 A case with genetically proven neuroferritinopathy5 had an MRI with a similar pencil lining as our cases on SWI, but this pattern or cortical SWI changes were not noted.

Discussion.

Neuroferritinopathy is caused by mutations in the FTL gene and deposits of “ferritin bodies” in the caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, cerebellar granule cells and Purkinje cells, and cortical gray matter.1 This topography matches closely with the regions with low magnetic susceptibility observed on MRI in our patients and in cases reported previously.4,5 It is also possible that pencil lining reflects excessive iron deposition in areas of the brain that are physiologically rich in iron predominantly in the gray matter.6,7

We did not have any cases of aceruloplasminemia available for review. It is possible that this sign may also be seen in aceruloplasminemia, which is another condition reported to have cortical iron deposition on T2* and fast spin echo MRI.4 However, aceruloplasminemia is a very rare disorder and, unlike the common NBIAs, there are certain specific features such as diabetes and anemia that can easily guide genetic testing.

We conclude that pencil lining, reflecting pathologic iron deposition in the periphery of the cortex and other gray matter structures, is a useful radiologic sign of neuroferritinopathy. Screening for FTL1 mutations should be considered first in an appropriate clinical setting, and also the presence of this sign.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Amit Batla: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation. Matthew E. Adams: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Roberto Erro: analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Christos Ganos: analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Bettina Balint: analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Niccolo E. Mencacci: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Kailash P. Bhatia: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision.

Study funding: No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure: A. Batla and M. Adams report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. R. Erro has been partly supported by COST Action BM1101 (reference: ECOST-STSM-BM1101-160913-035934) and has received travel grants by Ipsen. C. Ganos received Academic research support: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MU1692/2-1 and GA 2031/1-1) and European Science Foundation; commercial research support: travel grants by Actelion, Ipsen, Pharm Allergan, and Merz Pharmaceuticals. B. Balint and N. Mencacci report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. K. Bhatia receives royalties from publication of the Oxford Specialist Handbook Parkinson's Disease and Other Movement Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2008) and of Marsden's Book of Movement Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2012). He received funding for travel from GlaxoSmithKline, Orion Corporation, Ipsen, and Merz Pharmaceuticals. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Schneider SA, Hardy J, Bhatia KP. Syndromes of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA): an update on clinical presentations, histological and genetic underpinnings, and treatment considerations. Mov Disord 2012;27:42–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruer MC, Boddaert N, Schneider SA, et al. Neuroimaging features of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schipper HM. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation: clinical syndromes and neuroimaging. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1822:350–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNeill A, Birchall D, Hayflick SJ, et al. T2* and FSE MRI distinguishes four subtypes of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Neurology 2008;70:1614–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehn A, Mellick G, Boyle R. Teaching NeuroImages: neuroferritinopathy. Neurology 2011;77:e107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidal R, Ghetti B, Takao M, et al. Intracellular ferritin accumulation in neural and extraneural tissue characterizes a neurodegenerative disease associated with a mutation in the ferritin light polypeptide gene. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2004;63:363–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Wu B, Batrachenko A, et al. Differential developmental trajectories of magnetic susceptibility in human brain gray and white matter over the lifespan. Hum Brain Mapp 2014;35:2698–2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]