Background: Genome alterations need to be investigated before clinical application of iPS cells.

Results: Reprogramming and gene targeting can generate substantial but different genomic variations.

Conclusion: Stringent genomic monitoring and selection are needed both at the time of iPSC derivation and after gene targeting.

Significance: This study examined the genome instability during iPSC generation and subsequent gene correction and revealed different genome alterations at each step.

Keywords: Gene Therapy, Genomic Instability, Genomics, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPS Cell) (iPSC), Reprogramming

Abstract

The generation of personalized induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) followed by targeted genome editing provides an opportunity for developing customized effective cellular therapies for genetic disorders. However, it is critical to ascertain whether edited iPSCs harbor unfavorable genomic variations before their clinical application. To examine the mutation status of the edited iPSC genome and trace the origin of possible mutations at different steps, we have generated virus-free iPSCs from amniotic cells carrying homozygous point mutations in β-hemoglobin gene (HBB) that cause severe β-thalassemia (β-Thal), corrected the mutations in both HBB alleles by zinc finger nuclease-aided gene targeting, and obtained the final HBB gene-corrected iPSCs by excising the exogenous drug resistance gene with Cre recombinase. Through comparative genomic hybridization and whole-exome sequencing, we uncovered seven copy number variations, five small insertions/deletions, and 64 single nucleotide variations (SNVs) in β-Thal iPSCs before the gene targeting step and found a single small copy number variation, 19 insertions/deletions, and 340 single nucleotide variations in the final gene-corrected β-Thal iPSCs. Our data revealed that substantial but different genomic variations occurred at factor-induced somatic cell reprogramming and zinc finger nuclease-aided gene targeting steps, suggesting that stringent genomic monitoring and selection are needed both at the time of iPSC derivation and after gene targeting.

Introduction

Human iPSCs4 can undergo indefinite self-renewal while maintaining the potential to generate all somatic cell types in the body, thus opening up new ways for developmental biology research, disease modeling, and applications in regeneration medicine. Indeed, combining iPSC generation with targeted genome editing had been used for modeling various genetic diseases, including β-Thal (1, 2). β-Thal is one of the most common genetic diseases in the world, and patients suffering from severe anemia need regular blood transfusions. It is caused by mutations or deletions in the β-hemoglobin gene (HBB) that destroy the normal function of red blood cells (3, 4). Currently, transplantation of bone marrow from a healthy donor is the only way to cure β-Thal, but this treatment is limited by the lack of human leukocyte antigen-matched donors. Theoretically, the generation of iPSCs from β-Thal patients followed by targeted genome correction of mutated HBB could be an ideal new treatment for these diseases (5). The recent development of genome editing tools, such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) (6), transcriptional activator-like effector nucleases (7), and clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat/Cas9-based RNA-guided DNA endonucleases (8), has significantly improved gene targeting efficiency in human iPSCs or embryonic stem cells, thus making it practicable to generate personalized, gene-corrected iPSCs for cell therapy. However, it is critical to evaluate whether the reprogramming and the subsequent gene targeting steps generate unwanted genome alterations before application of this type of cellular therapy in clinical practice.

The generation of gene-corrected iPSCs requires factor-induced somatic reprogramming and nuclease-aided gene targeting steps. The impact on genome stability of reprogramming or gene targeting has drawn lots of attention. For example, it was reported that iPSCs carried more frequent CNVs than other cell lines, such as ES cells and somatic cells (9, 10). Some of these CNVs were certainly attributed to the reprogramming process (11–14). However, in another report, very few nucleotide level variations, such as non-synonymous single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (Indels), were found in iPSCs generated through a non-viral approach (15). Similarly, the impact on genome stability of genome-editing tools, such as transcriptional activator-like effector nucleases or clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat/Cas9, has also been analyzed (16). In general, these genome-editing tools seemed not to induce much genome variation based on the whole-genome sequencing data (17–19), suggesting that these tools might be safe for clinical applications.

The current study was designed to examine the genome variations generated throughout the process of producing gene-corrected β-Thal iPSCs, including iPSC generation through a non-viral approach, clonal selection, expansion, genome editing, and exogenous gene excision. We first generated an integration-free β-Thal iPSC line from amniocytes that carried homozygous point mutations in the second intron of HBB (site 654). We then corrected both mutated HBB alleles by ZFN-aided gene targeting and excised exogenous drug resistance genes to obtain the final HBB-corrected iPSCs. Next, we performed sequential CGHs and exome sequencing on parental cells used for iPSC derivation, iPSCs before gene correction, and the final gene-corrected β-Thal iPSCs. Our results showed that iPSC derivation even with a non-viral approach could generate a certain number of variations, including both CNVs and SNVs. Meanwhile, the subsequent ZFN-aided gene targeting caused negligible CNVs but a lot more SNVs. Our analysis indicated that factor-induced somatic cell reprogramming and ZFN-aided gene targeting tend to generate different genomic variations. These variations need to be carefully analyzed and evaluated before the clinical application of personalized gene-corrected iPSCs for cellular therapy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

iPSC Generation and Cell Culture

The methods of isolating amniotic fluid cells and iPSC generation from a β-thalassemia patient were performed as described previously (2, 20). The amniotic fluid cells were cultured in Amniogrow PLUS (Cytogen), and the iPS cells were maintained in mTeSR1 (Stemcell Technologies). All cell types were maintained at 5% CO2.

ZFNs and Donor Vectors for Gene Targeting

ZFNs were designed by Sigma-Aldrich. The ZFN pair was designed to target the 3′-side region that was ∼600 bp downstream of the last exon of HBB gene (see Fig. 1D, underlined). The HBB-ZFN pair recognition sequences were 5′-CACTCTTTCACAGTCTGC and 5′-CTAAGCCCAGTCCTT. They were expressed from two plasmids under the control of the CMV promoter. The left and right homology arms were amplified from genomic DNA of a healthy individual. The primer sets HBBL-F/R amplified the 2.3-kb left arm, and HBBR-F/R amplified the 1.5-kb right arm. A loxP-flanked PGK-neomycin cassette or loxP-flanked PGK-puromycin cassette were inserted between two homology arms into the pMD-18T vector (Takara). For targeting, 1 × 106 iPSCs were electroporated with 2 μg of donor DNA and 4.5 μg of each ZFN plasmid. Then the electroporated iPS cells were plated onto Matrigel-coated 6-well plates in the presence of Y-27632 (10 nm; Sigma) for 1 day. Positive clones were selected by puromycin (0.5 μg/ml) or G418 (100 μg/ml; Sigma) in mTeSR1. Primers sequences are listed in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Site-specific gene correction of the β-hemoglobin mutations using ZFNs. A, schematic of the GFP reporter assay for HBB-ZFNs. B, fluorescence images of 293T cells transfected with GFP reporter (top) or GFP reporter with ZFNs (bottom). C, specificity of HBB-ZFNs. We designed two GFP reporters, one containing the HBB-ZFN recognition sequence and the other containing a similar sequence in the genome. Values are mean ± S.D. (error bars) for triplicate samples from a representative experiment. p values were calculated by one-way analysis of variance. ** indicates p < 0.01. ZFN-L, one of the pair of HBB-ZFNs; ZFN-L/R, the pair of HBB-ZFNs. D, schematic overview of gene targeting strategy for the human HBB locus. The desired recombination event inserts a PGK promoter-puromycin resistance cassette or PGK promoter-neomycin resistance cassette flanked by loxP sites (green triangles) into the position about 600 bp downstream of the HBB locus. The Southern blot probe is indicated by short straight line (5′-probe), and PCR primers are indicated by arrows (F1/R1 and F2/R2). Mut, mutant. E, bright field images of cultured human βThal654_iPS, βThal654_iPSG2, βThal654_iPSG2Pu11, and βThal654_iPSCre16 cell colonies. Scale bars, 200 μm. F, genome PCR analysis of βThal654_iPS, βThal654_iPSG2, βThal654_iPSPu26, βThal654_iPSG2Pu11, and βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. βThal654_iPSPu26, a cell line with one HBB allele, was targeted by the donor template containing the puromycin resistant cassette. H2O, negative control. G, Southern blot of βThal654_iPS, βThal654_iPSG2, βThal654_iPSPu26, βThal654_iPSG2Pu11, and βThal654_iPSCre16 cells using the 5′-probe. The HBB allele that has not undergone gene targeting shows a 5-kb band, whereas a targeted allele shows a 6.4-kb band. H, sequencing results of C→T mutation site in the second intron of HBB in βThal654_iPS, βThal654_iPSG2, βThal654_iPSG2Pu11, and βThal654_ iPSCre16 cells. I, karyotype of βThal654_ iPSCre16 cells.

TABLE 1.

Primers list

F, forward; R, reverse.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| qACTIN-F | 5′-CCCAGAGCAAGAGAGG |

| qACTIN-R | 5′-GTCCAGACGCAGGATG |

| qOCT4-F | 5′-CCTCACTTCACTGCACTGTA |

| qOCT4-R | 5′-CAGGTTTTCTTTCCCTAGCT |

| qSOX2-F | 5′-CCCAGCAGACTTCACATGT |

| qSOX2-R | 5′-CCTCCCATTTCCCTCGTTTT |

| qNANOG-F | 5′-TGAACCTCAGCTACAAACAG |

| qNANOG-R | 5′-TGGTGGTAGGAAGAGTAAAG |

| F1 | 5′-GTAGCAATTTGTACTGATGGTATGGGGC |

| R1 | 5′-GGTGGATGTGGAATGTGTGCGAGG |

| F2 | 5′-CAGCCTTAGTTGTCTCTGTTGTCTTA |

| R2 | 5′-GGTGGTTGATGGTAACACTATGCTA |

| IVS-654-F | 5′-ATTGACCAAATCAGGGTAATTTTGC |

| IVS-654-R | 5′-GACAGCAAGAAAGCGAGCTTAGTGA |

| 5′probe-F | 5′-GGTAGGGGCAGGATTCAGGA |

| 5′probe-R | 5′-ATGGGGTAATCAGTGGTGTCAAAT |

| HBBR-F | 5′-CCGAAGCTTGAATTCCTCGAGATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGC |

| HBBR-R | 5′-AATCCCGGGGAATTCGTCGACGCGGCCGCGGTATACCTTGTGAAAT |

| HBBL-F | 5′-CCGAAGCTTGAATTCCTCGAGGCGGCCGCAGTGCCAGAAGAGCCAA |

| HBBL-R | 5′-AATCCCGGGGAATTCGTCGACATAACTTCGTATAGCATACAT |

| qCNV1-F | 5′-GGTGAGAAGGAATCAGAGGAATAAAGTT |

| qCNV1-R | 5′-TCTAGTACCTACACTTGTCATTGCCCAC |

| qCNV2-F | 5′-CCCTGCCGAATGAGTAAAGTAAA |

| qCNV2-F | 5′-CTGGGTGTTGAGTCTAGGCTCTATC |

| qCNV3-F | 5′-TTACTGGAACTAATAGGACACGCTG |

| qCNV3-R | 5′-TGGAGGCTGGCAAGAATGG |

| qCNV4-F | 5′-GGTCTTCTTACTTGCCGAATCCAC |

| qCNV4-R | 5′-GGTCTTCTTACTTGCCGAATCCAC |

| qCNV5-F | 5′-AATAGCGAACCATTTTCACAGATTACC |

| qCNV5-R | 5′-GTGCCTGTGAATTGACTCCTTCATT |

| qCNV6-F | 5′-CTCCCTACTTGGGTAAAGTTCTCCG |

| qCNV6-R | 5′-TTTGGAGACAGTTACCCGATTTAAGTAA |

| qCNV7-F | 5′-GCTGAGGCAGGAGAATGGCG |

| qCNV7-R | 5′-AGACGGAGTCTCGCTCTGTCGC |

| qCNV8-F | 5′-CTGTTTTGTCGGGTGAAGTGAGG |

| qCNV8-R | 5′-AGGAACCTGTCCGCCACATTC |

| qHBB locus-F | 5′-CCTTGGACCCAGAGGTTCTTTGA |

| qHBB locus-R | 5′-CATCACTAAAGGCACCGAGCACT |

PCR Detection of Corrected Clones

Genomic DNA was extracted using the TIANamp Genomic DNA kit (Tiangen) for PCR analysis. 50–100 ng of genomic DNA templates and LA Taq (Takara) were used in all PCRs. The primer set including P1 and P2 was used to amplify a 2.8-kb product of the 5′-junction of a targeted integration (see Fig. 1D). The primer set including P3 and P4 was used to amplify a 2-kb product or a 500-bp product to identify whether random integration occurred. The primer pair IVS-654-F/R was used to amplify a 600-bp product containing the mutant region of HBB, and then PCR products were sequenced to identify the corrected clones. All primers sequences are listed in Table 1.

Southern Blotting

A 502-bp HBB-specific probe in the 5′-side of the left homology arm was synthesized by PCR amplification using the primer pair 5′probe-F/R and DIG-dUTP labeling kit (Roche Applied Science). Genomic DNA was digested by BglII, and then standard Southern blotting was performed following the instructions of DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter kit II (Roche Applied Science).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cells were digested by 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen) and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 37 °C. After washing with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Excell) in PBS, cells were permeabilized with 90% methanol for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 30 min at 37 °C. Meanwhile, control samples were incubated with isotype control antibodies for 30 min at 37 °C. After washing, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed and resuspended in PBS and then analyzed on an Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) (21). The antibodies used were OCT3/4 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-5279), SSEA4 antibody (Abcam, AB16287), and HBB antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-21757).

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) (Takara), and then quantitative PCR was performed with a CFX96 machine (Bio-Rad) and a SYBR Green Premix EX TaqTM kit (Takara) following the manufacturers' instruction manuals. β-Actin was used for quantitative RT-PCR normalization, and all data were measured in triplicate. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Teratoma Formation and Analysis

βThal654_iPSCre16 cells cultured on a Matrigel-coated 10-cm plate were digested by Dispase (Invitrogen), resuspended in Matrigel (BD Biosciences), and then injected subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice. Teratomas were dissected after 8 weeks, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Erythroblast Differentiation of Human iPS Cells

βThal654_iPS and βThal654_iPSCre16 cells were harvested by Dispase (Invitrogen) digestion and co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells for 8 days at 2.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish in 20 ml of α-minimum Eagle's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone), 100 μm monothioglycerol (Sigma), and 100 μm vitamin C. Half of the culture medium was changed at days 4 and 6. CD34+ cells were directly sorted out using a CD34 Progenitor Cell Isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) at day 8. Hematopoietic colony-forming unit (cfu) assays were performed using 2 ml/dish MethoCult GF+ H4435 semisolid medium (Stemcell Technologies) following the manufacturer's instruction manuals on 35-mm low adherence plastic dishes (Monroe). The number of CD34+ cells sorted by magnetic activated cell sorting for cfu assays was about 5 × 105 cells. Colonies were counted after 12–14 days.

High Resolution Assay of Comparative Genomic Hybridization Microarray and Genome-wide Copy Number Variation Analyses

Genomic DNAs extracted from donor cells (amniotic fluid cells), βThal654_iPS cells, and βThal654_iPSCre16 cells were digested using AluI and RsaI enzymes. A SureTag DNA labeling kit (Agilent) was applied for DNA labeling. First, different fluorescence dyes were used for DNA labeling of βThal654_iPS cells (Cy5-dUTP) and the donor amniotic fluid cells (Cy3-dUTP). Labeled βThal654_iPS cell DNA was hybridized with the labeled donor cell DNA following the instruction manuals of the SurePrint G3 human CGH microarray kit (1 × 1 M, Agilent). Second, different fluorescence dyes were used for DNA labeling of βThal654_iPSCre16 cells (Cy5-dUTP) and βThal654_iPS cells (Cy3-dUTP). Labeled βThal654_iPSCre16 cell DNA was hybridized with the labeled βThal654_iPS cell DNA following the instruction manuals of the SurePrint G3 human CGH microarray kit (1 × 1 M, Agilent). We followed oligonucleotide array-based CGH protocol version 6.0 (Agilent) to process DNA samples and handle and scan microarray profiles. Then the microarray scanning profiles were processed and analyzed by Feature Extraction 10.7.3.1 (Agilent) and Workbench 7.0 (Agilent). The threshold of the Aberration Detection Method-2 algorithm was set to 6.0 with Fuzzy Zero. CNVs were named by at least four consecutive probes with log2 ratio (samples were labeled with a ratio of fluorescent Cy5 and Cy3) consistent with duplication or deletion (duplication and deletion are larger than 1 kb).

Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNAs were extracted from donor amniotic fluid cells, βThal654_iPS cells, and βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. We used SeqCap EZ Exome 64M (Roche NimbleGen) and a TruSeq DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina) to capture the exome and establish the exome sequencing library following the manufacturers' instruction manuals. All sequencing was carried out on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer with a paired end 2 × 100-nucleotide multiplex. Human genome build GRCh37 (hg19) was selected as the reference human genome in these analyses. The 2 × 100-nucleotide paired-end reads were mapped onto the human reference genome using Burrows-Wheeler Alignment version 0.5.9. Potential PCR repetitions were removed using Samtools (version 0.1.18), and mapping profiles were analyzed using flagstat.

SNV and Indel Analyses

Targeted genomic regions had at least 30× coverage. Candidate βThal654_iPS mutations were defined as variants that were present in a given βThal654_iPS exome but not in the donor amniotic cells, and candidate βThal654_iPSCre16 mutations were defined as variants that were present in a given βThal654_iPSCre16 exome but not in βThal654_iPS. To exclude the false positives caused by insufficient depths of exome sequencing, we first filtered out the Indels and SNVs with coverage of sequencing depth less than 10×. For Indel analysis, we also filtered out the direct repeats, homopolymers, and repetitive sequences that were caused by the technical limitation of high throughput, short read sequencing technologies (16). Selected SNVs and Indels were validated by Sanger sequencing. All primers sequences are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Correction of Homozygous Mutations of HBB Genes in β-Thal iPSCs with Aid of ZFNs

We have previously derived an iPSC line from the amniotic cells of a fetus that was diagnosed with β-Thal major (IVS2-654), which was named βThal654_iPS. The cell line carries two homozygous C→T mutations at the second intron of HBB gene (2). A reporter assay showed that our ZFNs designed for HBB targeting exhibited satisfactory activity and specificity (2) (Fig. 1, A, B, and C). We failed to obtain an iPSC line with both HBB alleles corrected through one round of gene targeting. Thus, we used a two-step strategy to correct mutated HBB alleles sequentially with HBB-specific ZFNs (Fig. 1D). Then we constructed two targeting vectors containing different drug resistance genes, one for neomycin and the other for puromycin, to achieve homologous recombination for gene targeting (Fig. 1D). We first introduced the neomycin-resistant donor template together with ZFNs into the βThal654_iPSCs. After selected by G418, we obtained the iPSCs with a single HBB allele targeted, which were named βThal654_iPSG2 (Fig. 1E). The correction was further confirmed by genomic PCR, Southern blotting, and Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1, F, G, and H). Similarly, we introduced the second donor template with the puromycin resistance gene and ZFNs into βThal654_iPSG2 and obtained an iPSC line with both HBB alleles targeted, which was named βThal654_iPSG2Pu11 (Fig. 1E). Both drug resistance genes were then excised by Cre recombinase to generate the final gene-corrected iPSCs, which were named βThal654_iPSCre16 (Fig. 1E). The iPS clone was validated by genomic PCR and Southern blotting (Fig. 1, F and G). Lastly, by Sanger sequencing, we confirmed that the C→T mutations of both alleles were both corrected in βThal654_iPSCre16 (Fig. 1H). G binding analysis showed that both uncorrected (2) and corrected β-Thal iPSCs maintained a normal karyotype (Fig. 1I).

Characterization of the Gene-corrected iPSC

The gene-corrected βThal654_iPSCre16 exhibited typical human embryonic stem cell morphology (Fig. 1E) and expressed pluripotent markers, such as OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and SSEA4, as detected by FACS and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2, A and B). Upon injection into immunodeficient mice, the corrected βThal654_iPSCre16 cells could form teratomas containing all three germ layers (Fig. 2C). These data demonstrate that the pluripotency of iPSCs was maintained after ZFN-mediated gene targeting.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization and erythroblast differentiation of corrected β-Thal iPS cells. A, flow cytometry expression analysis of iPS cell-specific markers in βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. Red, isotype control; blue, antigen staining for OCT4 or SSEA4. B, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of endogenous OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG expression in βThal654_iPS, βThal654_iPSCre16, and H1 (human embryonic stem cell line) as a positive control. The data are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three assays. C, H&E staining of teratomas derived from βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. Scale bars, 200 μm. D, bright field images of cfu derived from βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. G, granulocytes; E, erythroblasts; M, megakaryocytes. E, ratio of different types of colonies counted at day 21 after differentiation. E, erythroblasts; G, granulocytes; M, megakaryocytes; GM, granulocytes and megakaryocytes; GEMM, four types of colonies, including granulocytes, erythrocytes, megakaryocytes, and macrophages. F, flow cytometry expression analysis of HBB in erythroblasts derived from βThal654_ iPS and βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. Black, isotype control; orange, antigen staining for HBB.

To further examine whether the correction of disease-causing mutations could restore the normal expression of HBB, we performed hematopoietic differentiation of uncorrected and corrected β-Thal iPS cells based on an OP9 co-culture protocol described previously (2, 22). Upon OP9 co-culture, both uncorrected and corrected β-Thal iPS cells could differentiate rapidly and produce the CD34+/43+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (23). These iPSC-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells could further differentiate into various mature blood lineages as analyzed by a cfu assay (Fig. 2D). Upon plating in a semisolid culture system, all types of colonies could be observed, including erythrocyte, granulocyte, megakaryocyte, granulocyte/megakaryocyte, erythrocyte/granulocyte/megakaryocyte/macrophage (Fig. 2E). To examine the expression of HBB, we manually picked out erythrocyte colonies and analyzed the expression of HBB by quantitative RT-PCR and FACS. Because that the C→T mutation at the second intron of HBB leads to abnormal splicing of the full-length mRNA, its correction should restore the normal expression level of β-globin in red blood cells. Indeed, we showed that the level of β-globin significantly increased in gene-corrected β-Thal iPSCs compared with their uncorrected counterparts (Fig. 2F). Thus, these data demonstrate that the gene-corrected β-Thal iPSCs maintained the capability of differentiation into blood lineages and that our correction restored the expression of HBB.

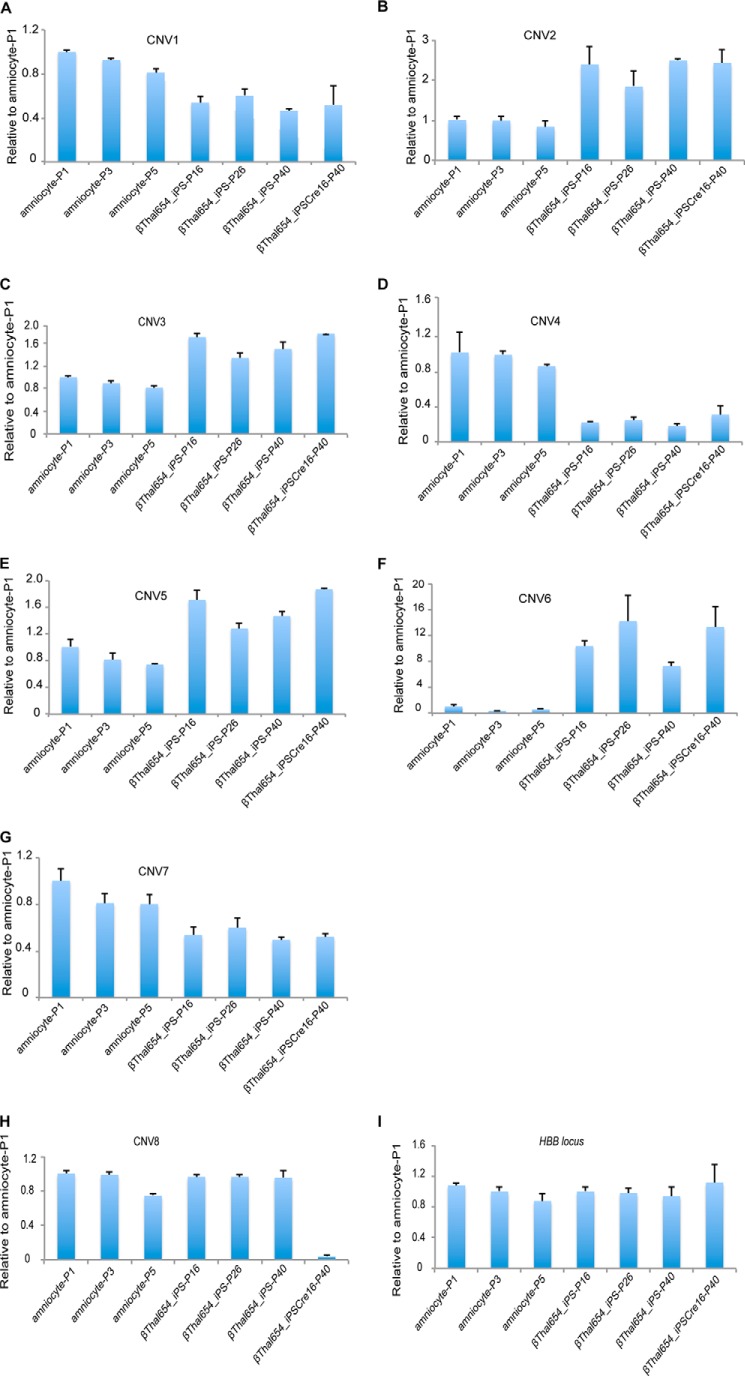

Copy Number Variations

To assess the subchromosomal changes during the process of reprogramming and gene targeting, we performed sequential aCGH on the original amniocytes, amniocyte-derived βThal654_iPS cells, and gene-corrected βThal654_iPSCre16 cells (Fig. 3). Using the genome of the original donor cells as a reference, aCGH detected a number of large fragment deletions and duplications in βThal654_iPS cells after reprograming, including three deletions and four duplications that impacted 20 genes (Table 2). Surprisingly, we only detected one small deletion in gene-corrected βThal654_iPSCre16 (Table 3) when compared with the genome of its uncorrected counterpart. All CNVs detected by aCGH were further verified by quantitative genomic PCR (Fig. 4). These data indicate that the gene targeting process might not lead to large fragment abnormality of the genome even though it underwent multiple clonal events and genome editing. To rule out CNVs potentially caused by long term cell culturing, we reanalyzed the detected CNVs in the parental amniocytes and uncorrected iPSCs with different passages. As expected, we failed to detect the existence of such CNVs in parental amniocytes with different passages by using quantitative PCR. Moreover, the CNVs detected in iPSCs remained the same even with prolonged expansion and passages (Fig. 4). These data indicate that CNV generation occurred during the reprogramming or gene targeting process rather than during cell expansion and passaging.

FIGURE 3.

aCGH analysis of copy number variations in amniotic cells, βThal654_ iPS cells, and corrected βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. A, overview of aCGH comparison between βThal654_iPS cells and amniotic cells. B, overview of aCGH comparison between βThal654_iPSCre16 cells and βThal654_iPS cells. C, a representative duplication example of CNVs between βThal654_iPS cells and amniocytes. D, a representative deletion example of CNVs between βThal654_iPS cells and amniocytes. E, a representative deletion example of CNVs between βThal654_iPSCre16 cells and βThal654_iPS cells. Red, duplication; green, deletion; blue shading, copy number variation region.

TABLE 2.

CNVs detected in the βThal654_iPS versus amniocytes

Chr, chromosome.

| Chr | Region | Size | Genes | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 89728229–89744460 | 16 kb | DPY19L2P4 | Deletion |

| 10 | 90636108–90711123 | 75 kb | STAMBPL1, ACTA2 | Duplication |

| 10 | 90959017–92031184 | 1.1 Mb | CH25H, LIPA, IFIT2, IFIT3, IFIT1B, IFIT1, IFIT5, SLC16A12, PANK1, MIR107, FLJ37201, KIF20B | Duplication |

| 10 | 93743987–94339488 | 556 kb | BTAF1, CPEB3, MARCH5, IDE | Deletion |

| 10 | 95030562–95051674 | 21 kb | Duplication | |

| 17 | 1957745–1962621 | 5 kb | HIC1 | Duplication |

| 18 | 27871290–27875270 | 4 kb | Deletion |

TABLE 3.

CNVs detected in the βThal654_iPSCre16 versus βThal654_iPS

Chr, chromosome.

| Chr | Region | Size | Genes | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kb | ||||

| 20 | 1563632–1584485 | 21 | SIRPB1 | Deletion |

FIGURE 4.

Genomic DNA-based quantitative PCR analysis of CNVs. A, deletion of chromosome 7 (89728229–89744460). B, duplication of chromosome 10 (90636108–90711123). C, duplication of chromosome 10 (90959017–92031184). D, deletion of chromosome 10 (93743987–94339488). E, duplication of chromosome 10 (95030562–95051674). F, duplication of chromosome 17 (1957745–1962621). G, deletion of chromosome 18 (27871290–27875270). H, deletion of chromosome 20 (1563632–1584485). I, HBB locus was used as a control. Values are mean ± S.D. (error bars) for triplicate samples from a representative experiment. Amniocyte-P1, amniocyte-P3, and amniocyte-P5 are amniocytes with different passages. βThal654_iPS-P16, βThal654_iPS-P26, and βThal654_iPS-P40 are uncorrected iPS cells with different passages. βThal654_iPSCre16-P40 are corrected iPS cells of passage 40. Amniocyte-P3 cells were the original cells used for reprogramming, βThal654_iPS-P16 cells were the original cells used for gene targeting and aCGH analysis, and βThal654_iPS-P40 cells were the parallel passaged uncorrected iPS cells with corrected βThal654_iPSCre16-P40 cells.

Indels and SNVs

To detect the minor genomic changes at the nucleotide level, we performed whole exome sequencing on the original amniocytes, amniocyte-derived βThal654_iPS cells, and corrected βThal654_iPSCre16 cells. In comparison with the parental donor cells, we detected a total of 83 Indels in βThal654_iPS cells before targeting. Consistent with previous reports that Indel calling usually generates a high rate of false positives (15, 24, 25), only five of 83 called Indels passed the more stringent bar. We confirmed that most of the false positive Indels were located within highly repetitive regions. With the same stringent bar set for Indel calling (see “Experimental Procedures”), we detected 19 Indels in gene-corrected iPS cells (Table 4). These data indicate that the gene targeting process tends to trigger more nucleotide level variations than the reprogramming process. Among them, only one of the 19 Indels found in corrected iPS cells affected the coding region of one known gene.

TABLE 4.

Summary of Indels

| βThal654_iPS vs. amniocytes | βThal654_iPSCre16 vs. βThal654_iPS | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Indels | 83 | 597 |

| High quality filtered Indels | 5 | 19 |

| Indels in intergenic regions | 0 | 4 |

| Indels in introns | 5 | 12 |

| Indels in 5′- or 3′-UTR | 0 | 2 |

| Indels in coding regions | 0 | 1 |

We also detected a fair number of SNVs generated by reprogramming and gene targeting (Table 5). Again, we found many more SNVs generated by gene targeting than by reprogramming (45 nonsynonymous SNVs in gene-corrected iPSCs versus two in uncorrected iPSCs; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Summary of SNVs

S, synonymous; NS, nonsynonymous.

| βThal654_iPS vs. amniocytes | βThal654_iPSCre16 vs. βThal654_iPS | |

|---|---|---|

| Total SNVs | 4853 | 5031 |

| High quality filtered SNVs | 64 | 340 |

| SNVs in intergenic regions | 14 | 49 |

| SNVs in introns | 33 | 169 |

| SNVs in 5′- or 3′-UTR | 10 | 30 |

| SNVs in coding regions | 7 | 92 |

| Synonymous | 5 | 46 |

| Nonsynonymous | 2 | 45 |

| Stop gain | 0 | 1 |

| NS:S ratio | 2.5 | 1.02 |

We further examined whether these SNVs could be generated through long term culturing and multiple passaging before gene targeting. We randomly selected seven SNVs detected in uncorrected iPSCs (at passage16) and reanalyzed them by Sanger sequencing in parental amniocytes or βThal654_iPS cells with different passages (passages 1, 3, 5, and 7 for amniocytes and passages 16 and 26 for iPSCs). The results showed that all the randomly selected SNVs were absent in both parental amniocytes and iPS cells regardless of passage number (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Sanger sequencing results of randomly selected SNVs in different passages of aminocytes and βTha1654_iPS cells

Regarding newly generated SNVs in gene-corrected iPS cells, we found that these SNVs were maintained in corrected iPSCs through multiple passages but never present in uncorrected iPS cells (Table 7). These data exclude the possibility that long term culturing and multiple passaging generate genome variations during reprogramming and gene targeting.

TABLE 7.

Sanger sequencing results of randomly selected SNVs in different passages of βTha1654_iPS cells and βTha1654_iPSCre16 cells

DISCUSSION

iPS technology combined with gene targeting provides new ways to treat or investigate genetic diseases. However, safe evaluation standards of these genetically modified personalized iPSCs are lacking. Genomic variation is an important parameter to be considered for safe clinical application. In this study, by using β-Thal iPS cells as a model, we assessed genomic variations generated during factor-induced reprogramming and subsequent gene correction mediated by ZFN-aided gene targeting processes. We found that both factor-induced reprogramming and ZFN-aided gene targeting affected the genome integrity but at different levels. A fair number of large fragment variations (CNVs) were detected in β-Thal iPS cells after reprogramming, whereas few CNVs occurred during gene targeting. In contrast, gene targeting tends to generate nucleotide level variations rather than cause large fragment changes. It was not clear whether these variations were due to the off-target effect of ZFN or caused by multiple rounds of clonal selections. We indeed detected more SNVs in chromosome 20 than in other chromosomes (Fig. 5), but no evidence was found to support that the HBB ZFNs were prone to recognize the sequence in chromosome 20.

FIGURE 5.

The chromosome distribution of high quality filtered SNVs. A, the chromosome distribution of high quality filtered SNVs in βThal654_iPS cells versus amniocytes. I, βThal654_iPS; D, amniocytes. B, the chromosome distribution of high quality filtered SNVs in βThal654_iPSCre16 versus βThal654_iPS. C, βThal654_iPSCre16; I, βThal654_iPS.

Other recent studies reported that the genome-editing tools did not seem to generate more intolerable variations at the single nucleotide level, such as SNVs or Indels (16). However, in final gene-corrected β-Thal iPS cells, we did detect three Indels and 46 nonsynonymous SNVs that could affect known gene functions. Considering that the whole gene correction process described here contains two rounds of gene targeting and one round of drug resistance gene excision, the numbers of detected SNVs and Indels are comparable with those of previous reports. With the decreasing cost of genome sequencing, it is possible and necessary to carefully assess these variations before further clinical application in the future. In addition, it is difficult to assess the subchromosomal changes based solely on the genome sequencing data (15). By using aCGH, we detected a fair number of CNVs in β-Thal iPSCs after the reprogramming process. However, the subsequent gene targeting and drug selection cassette excision generated minimal additional CNV changes. Our data suggest that reprogramming and gene targeting cause different genomic variations, and these variations need to be analyzed by appropriate approaches in the safety evaluation process before clinical applications.

Acknowledgment

We thank the members of our laboratory for kind help. We also thank Dr. Feng Zhang and Yulin Chen (State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering and Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Contemporary Anthropology, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China) for performing the CGH experiments and analyzing and providing the CGH data.

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China, 973 Program of China (Grant 2012CB966503), “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant XDA01020202), National Scientific and Technological Major Special Project on Major New Drug Innovation (Grant 2011ZX09102-010), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 31200970), “Hundred Talents Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (to G. P.), “Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences,” “Pearl River Nova program” (to B. L.), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada Discovery Grant (RGPIN/328095-2014, to N. C.), and International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of China (Grant 2014DFA30180).

The exome sequencing data reported in this study have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at NCBI under accession number SRP047149.

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- HBB

- β-hemoglobin

- β-Thal

- β-thalassemia

- ZFN

- zinc finger nuclease

- CGH

- comparative genomic hybridization

- CNV

- copy number variation

- Indel

- insertion/deletion

- SNV

- single nucleotide variation

- aCGH

- array comparative genomic hybridization

- iPS

- induced pluripotent stem

- PGK

- phosphoglycerate kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang Y., Zheng C. G., Jiang Y., Zhang J., Chen J., Yao C., Zhao Q., Liu S., Chen K., Du J., Yang Z., Gao S. (2012) Genetic correction of β-thalassemia patient-specific iPS cells and its use in improving hemoglobin production in irradiated SCID mice. Cell Res. 22, 637–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ma N., Liao B., Zhang H., Wang L., Shan Y., Xue Y., Huang K., Chen S., Zhou X., Chen Y., Pei D., Pan G. (2013) Transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN)-mediated gene correction in integration-free beta-thalassemia induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 34671–34679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olivieri N. F. (1999) The β-thalassemias. New Engl. J. Med. 341, 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin A., Thompson A. A. (2013) Thalassemias. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 60, 1383–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanna J., Wernig M., Markoulaki S., Sun C. W., Meissner A., Cassady J. P., Beard C., Brambrink T., Wu L. C., Townes T. M., Jaenisch R. (2007) Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science 318, 1920–1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Urnov F. D., Rebar E. J., Holmes M. C., Zhang H. S., Gregory P. D. (2010) Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 636–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller J. C., Tan S., Qiao G., Barlow K. A., Wang J., Xia D. F., Meng X., Paschon D. E., Leung E., Hinkley S. J., Dulay G. P., Hua K. L., Ankoudinova I., Cost G. J., Urnov F. D., Zhang H. S., Holmes M. C., Zhang L., Gregory P. D., Rebar E. J. (2011) A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P. D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L. A., Zhang F. (2013) Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma H., Morey R., O'Neil R. C., He Y., Daughtry B., Schultz M. D., Hariharan M., Nery J. R., Castanon R., Sabatini K., Thiagarajan R. D., Tachibana M., Kang E., Tippner-Hedges R., Ahmed R., Gutierrez N. M., Van Dyken C., Polat A., Sugawara A., Sparman M., Gokhale S., Amato P., Wolf D. P., Ecker J. R., Laurent L. C., Mitalipov S. (2014) Abnormalities in human pluripotent cells due to reprogramming mechanisms. Nature 511, 177–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liang G., Zhang Y. (2013) Genetic and epigenetic variations in iPSCs: potential causes and implications for application. Cell Stem Cell 13, 149–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abyzov A., Mariani J., Palejev D., Zhang Y., Haney M. S., Tomasini L., Ferrandino A. F., Rosenberg Belmaker L. A., Szekely A., Wilson M., Kocabas A., Calixto N. E., Grigorenko E. L., Huttner A., Chawarska K., Weissman S., Urban A. E., Gerstein M., Vaccarino F. M. (2012) Somatic copy number mosaicism in human skin revealed by induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 492, 438–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Laurent L. C., Ulitsky I., Slavin I., Tran H., Schork A., Morey R., Lynch C., Harness J. V., Lee S., Barrero M. J., Ku S., Martynova M., Semechkin R., Galat V., Gottesfeld J., Izpisua Belmonte J. C., Murry C., Keirstead H. S., Park H. S., Schmidt U., Laslett A. L., Muller F. J., Nievergelt C. M., Shamir R., Loring J. F. (2011) Dynamic changes in the copy number of pluripotency and cell proliferation genes in human ESCs and iPSCs during reprogramming and time in culture. Cell Stem Cell 8, 106–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hussein S. M., Batada N. N., Vuoristo S., Ching R. W., Autio R., Närvä E., Ng S., Sourour M., Hämäläinen R., Olsson C., Lundin K., Mikkola M., Trokovic R., Peitz M., Brüstle O., Bazett-Jones D. P., Alitalo K., Lahesmaa R., Nagy A., Otonkoski T. (2011) Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature 471, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Y., Guo L., Chen J., Zhao X., Zhou W., Zhang C., Wang J., Jin L., Pei D., Zhang F. (2014) Genome-wide CNV analysis in mouse induced pluripotent stem cells reveals dosage effect of pluripotent factors on genome integrity. BMC Genomics 15, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheng L., Hansen N. F., Zhao L., Du Y., Zou C., Donovan F. X., Chou B. K., Zhou G., Li S., Dowey S. N., Ye Z., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Chandrasekharappa S. C., Yang H., Mullikin J. C., Liu P. P. (2012) Low incidence of DNA sequence variation in human induced pluripotent stem cells generated by nonintegrating plasmid expression. Cell Stem Cell 10, 337–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsai S. Q., Joung J. K. (2014) What's changed with genome editing? Cell Stem Cell 15, 3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Veres A., Gosis B. S., Ding Q., Collins R., Ragavendran A., Brand H., Erdin S., Cowan C. A., Talkowski M. E., Musunuru K. (2014) Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell Stem Cell 15, 27–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suzuki K., Yu C., Qu J., Li M., Yao X., Yuan T., Goebl A., Tang S., Ren R., Aizawa E., Zhang F., Xu X., Soligalla R. D., Chen F., Kim J., Kim N. Y., Liao H. K., Benner C., Esteban C. R., Jin Y., Liu G. H., Li Y., Izpisua Belmonte J. C. (2014) Targeted gene correction minimally impacts whole-genome mutational load in human-disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cell clones. Cell Stem Cell 15, 31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith C., Gore A., Yan W., Abalde-Atristain L., Li Z., He C., Wang Y., Brodsky R. A., Zhang K., Cheng L., Ye Z. (2014) Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN-based genome editing in human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell 15, 12–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cai J., Li W., Su H., Qin D., Yang J., Zhu F., Xu J., He W., Guo X., Labuda K., Peterbauer A., Wolbank S., Zhong M., Li Z., Wu W., So K. F., Redl H., Zeng L., Esteban M. A., Pei D. (2010) Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from umbilical cord matrix and amniotic membrane mesenchymal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11227–11234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xue Y., Cai X., Wang L., Liao B., Zhang H., Shan Y., Chen Q., Zhou T., Li X., Hou J., Chen S., Luo R., Qin D., Pei D., Pan G. (2013) Generating a non-integrating human induced pluripotent stem cell bank from urine-derived cells. PLoS One 8, e70573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vodyanik M. A., Bork J. A., Thomson J. A., Slukvin I. I. (2005) Human embryonic stem cell-derived CD34+ cells: efficient production in the coculture with OP9 stromal cells and analysis of lymphohematopoietic potential. Blood 105, 617–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choi K. D., Vodyanik M. A., Togarrati P. P., Suknuntha K., Kumar A., Samarjeet F., Probasco M. D., Tian S., Stewart R., Thomson J. A., Slukvin I. I. (2012) Identification of the hemogenic endothelial progenitor and its direct precursor in human pluripotent stem cell differentiation cultures. Cell Rep. 2, 553–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ajay S. S., Parker S. C., Abaan H. O., Fajardo K. V., Margulies E. H. (2011) Accurate and comprehensive sequencing of personal genomes. Genome Res. 21, 1498–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kinde I., Wu J., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (2011) Detection and quantification of rare mutations with massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9530–9535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]