Background: IDO functions as a crucial mediator of tumor-mediated immune tolerance.

Results: Here, we found that GSK-3β-dependent IDO expression in the dendritic cell plays a role in anti-tumor activity via the regulation of CD8+ T-cell proliferation and CTL activity.

Conclusion: GSK-3β activity functions in the immune enhancement-mediated anti-tumor response via IDO regulation.

Significance: We proved the effectiveness of the GSK-3β-dependent IDO regulatory mechanism in DC-based cancer vaccination.

Keywords: cancer biology; dendritic cell; glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3); indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1); interferon; cancer vaccine

Abstract

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) functions as a crucial mediator of tumor-mediated immune tolerance by causing T-cell suppression via tryptophan starvation in a tumor environment. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) is also involved in immune and anti-tumor responses. However, the relativity of these proteins has not been as well defined. Here, we found that GSK-3β-dependent IDO expression in the dendritic cell (DC) plays a role in anti-tumor activity via the regulation of CD8+ T-cell polarization and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. By the inhibition of GSK-3β, attenuated IDO expression and impaired JAK1/2-Stat signaling crucial for IDO expression were observed. Protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) activity and the interaction between JAK1/2 and Stat3, which are important for IDO expression, were also reduced by GSK-3β inhibition. CD8+ T-cell proliferation mediated by OVA-pulsed DC was blocked by interferon (IFN)-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity. Specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity mediated by OVA-pulsed DC against OVA-expressing EG7 thymoma cells but not OVA-nonexpressing EL4 thymoma cells was also attenuated by the expressed IDO via IFN-γ-induced activation of GSK-3β. Furthermore, tumor growth that was suppressed with OVA-pulsed DC vaccination was restored by IDO-expressing DC via IFN-γ-induced activation of GSK-3β in an OVA-expressing murine EG7 thymoma model. Taken together, DC-based immune response mediated by interferon-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity not only regulates CD8+ T-cell proliferation and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity but also modulates OVA-pulsed DC vaccination against EG7 thymoma.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs)4 are known to help coordinate the immune system because they play a crucial role in both the induction of immunity and the triggering of T-cell tolerance (1). The DC is an antigen-presenting cell and is deeply involved in immunity via processes that include the capture, processing, and presentation of antigens to T-cells (2). Regarding tolerance, a DC phenotype that is tolerogenic plays a role in immune tolerance. The immunoregulatory enzyme, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which is an essential enzyme that degrades the amino acid tryptophan via the kynurenine pathway, contributes to that tolerance by causing T-cell suppression via tryptophan depletion (1, 3). In a tumor environment, an IDO that is highly expressed by tumor cells has been reported to function as a crucial mediator of tumor-mediated immune tolerance (4–6). Although DCs are crucial for initiating a primary T-cell response (7), IDO-positive DCs are thought to be important in the generation and maintenance of peripheral tolerance via the induction of regulatory T-cell responses (8).

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is known as an inducer of IDO in many cells, including DCs, macrophages, and various cancer cells (9). Transcriptional induction of the IDO gene is mediated by Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and Stat1 (10). Stat1 acts both directly and indirectly. It works directly by binding to the IFN-γ-activated sites within the IDO promoter. Also, it acts indirectly by inducing IFN regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1), which binds to the IDO promoter at two IFN-stimulated response element sites (11). In a previous study, we noted that IFN-γ-induced IDO expression is regulated by both the JAK1/2-Stat1 pathway and the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway (12).

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase found in all eukaryotes, was initially identified as a key regulator of insulin-dependent glycogen synthesis (13). In addition, GSK-3β is known to be involved in diverse cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, motility, and survival (14). Furthermore, dysregulation of GSK-3β has also been implicated in tumorigenesis and cancer progression (14). In recent studies, the role of GSK-3 as a regulator of immune responses, including activation and differentiation of DCs and endotoxemia, has been reported (15–17). Also, GSK-3-mediated regulation of Stat3 in primary astrocytes of the cerebral cortex was demonstrated (18).

Here, we defined the role and regulatory mechanism of GSK-3β in Stat-mediated IDO expression. Using a DC-based tumor vaccination murine model, we examined the substantial role of GSK-3β involved in IDO expression via the JAK1/2-Stat signaling cascade in DCs, representative cells of initiating the immune response and mediating T-cell proliferation and CTL responses against EG7 thymoma.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Eight- to 10-week-old male C57BL/6 (H-2Kb and I-Ab) mice were purchased from the Korean Institute of Chemistry Technology (Daejeon, Korea). C57BL/6 OT-I T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic and IDO−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment within our animal facility and used in accordance with the institutional guidelines for animal care. All experiments were done in accordance with the guidelines of the committee of Ethics of Animal Experiments, Konkuk University.

Cell Line

The EG7 cell line, an ovalbumin (OVA)-expressing EL4 variant, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 mm l-glutamine (all purchased from Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. GSK-3β+/+ and GSK-3β−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (19) were generously provided by Dr. J. R. Woodgett (Ontario Cancer Institute, Toronto, Canada), and GSK-3β+/+, GSK-3β−/− MEFs were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Reagents and Antibodies

Recombinant mouse (rm) granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), rm interleukin 4 (rm IL-4), and rm INF-γ were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); rottlerin was from Calbiochem. SB415286, a GSK-3β-specific inhibitor, was from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (FITC) or phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (Abs) that were used to detect the expression of CD11c (HL3), CD4, and CD8 (Lyt-2) were purchased from Pharmingen. The antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follow: anti-phospho-Stat3 (Ser-727), anti-phospho-GSK-3β (Ser-9), anti-Stat3, anti-Stat1, anti-JAK1, anti-JAK2, anti-phospho-JAK1, and anti-phospho-JAK2 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); anti-mouse IDO (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego); anti-tubulin, anti-GSK-3β, anti-β-catenin, anti-phospho-PKCδ, anti-PKCδ, anti-phospho-Stat1, and anti-IRF1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Silencing of GSK-3β by siRNA

To knock down GSK-3β, BMDCs were transfected with the four sequence pools (ON-TARGET plus SMART pool, LU-001080-00-0020, mouse GSK-3β, NM_019827 (Dharmacon Lafayette, CO)) using the DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, BMDCs were seeded in 12-well plates at 80–90% confluence; the medium was replaced with complete RPMI 1640 medium without antibiotics before transfection. DharmaFECT 1 and siRNA products were incubated separately in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium at room temperature for 5 min. Mixtures were combined, incubated for another 20 min, and added to the cells at the final concentration of 2 μl/ml DharmaFECT 1 and 25 nm siRNAs. For IFN-γ stimulation, siRNA and the transfection reagent were removed 24 h post-transfection, and the complete culture medium was added.

Generation and Culture of DCs

Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from the tibiae and femurs of 6–8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice and depleted of red blood cells (RBCs) using a red blood cell lysing buffer (Sigma). The cells were then plated in 6-well culture plates (1 × 106 cells/ml; 2 ml per well) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 20 ng/ml rmGM-CSF, and 10 ng/ml rmIL-4 at 37 °C in 5% CO2. On days 3 and 5, the floating cells were gently removed from the cultures, and fresh medium was added. On day 6 of culture, nonadherent cells and loosely adherent proliferating dendritic cell aggregates were harvested and re-plated in 60-mm dishes (1 × 106 cells/ml; 5 ml/dish) for stimulation and analysis. On day 7, 80% or more of the nonadherent cells expressed CD11c. In certain experiments, the DCs were labeled with bead-conjugated anti-CD11c mAb (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany) and then subjected to positive selection through paramagnetic columns (LS columns; Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer's instructions, to obtain highly purified populations for subsequent analysis. The purity of the selected cell fraction was >90%.

Immunofluorescence Assay

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and were incubated with IDO antibody purchased from Alexis. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. All images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (AX10; Carl Zeiss, Germany). The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Immunoblot Analysis

In brief, cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The PVDF membranes were then blocked with 5% nonfat milk in a washing buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with the indicated antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences). Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences).

Coimmunoprecipitation Analysis

In brief, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (20), and the lysates were subjected to 10 min of microcentrifugation at 12,000 × g. The soluble fraction was then incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with the appropriate antibodies, after which the mixture was incubated for an additional 1 h at 4 °C with protein G-coupled Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences). The resultant precipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed via immunoblotting.

Mixed Leukocyte Reaction

Transgenic OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells or CD4+ T-cells were purified from bulk splenocytes via negative selection by using CD4+ T cell isolation kit and CD8+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The purity of the obtained cell population was assessed to be >93% by flow cytometry after staining with a Cy5-conjugated anti-CD8 Ab. Briefly, the cells were resuspended in 5 μm carboxyfluroscein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and shaken for 10 min at room temperature. Next, the cells were washed once in pure FBS and twice in PBS with 10% FBS. Immature DCs, OVA-pulsed DCs, OVA-pulsed and IFN-γ-treated DCs, or OVA-pulsed IFN-γ and GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs were cultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes of OT-I T-cell receptor transgenic mice (1 × 106 per well) for 96 h. After 4 days, the cells were harvested and stained with Cy5-labeled anti-CD8 Ab (to gate OT-I T-cells) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytokine Analysis

The levels of IFN-γ were measured, using an ELISA kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays

To determine the effect of IFN-γ and GSK-3β on OVA-specific CTLs, cytotoxicity assays were performed. In mixed cultures, immature DCs, OVA-pulsed DCs, OVA-pulsed and IFN-γ-treated DCs, or OVA-pulsed IFN-γ and GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs were first cultured with splenocytes of OT-I TCR transgenic mice (1 × 106 per well) for 72 h and then co-cultured with EL4 (1 × 106 cells stained with 1 μm CFSE) or EG7 cells (1 × 106 cells stained with 10 μm CFSE). After 4 h, the mixed lymphocyte tumor cultures were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Preventive Tumor Challenge Experiments

Mice were intraperitoneally injected once a week for 3 weeks with immature DCs, OVA-pulsed DCs, OVA-pulsed and IFN-γ-treated DCs, or OVA-pulsed IFN-γ and GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs, followed by subcutaneous injection of EG7 thymoma cells (1 × 106) into the right lower back. The tumor size was measured every 4 days, and the tumor mass was calculated as follows: V = (2A × B)/2, where A is the length of the short axis, and B is the length of the long axis.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times, and consistent results were obtained. Unless otherwise stated, data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. Analysis of variance was used to compare experimental groups with control values, whereas comparisons between multiple groups were made using Tukey's multiple comparison tests (Prism 3.0 GraphPad software). p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

GSK-3β Activity Is Crucial for the Expression and Activity of IDO via the JAK1/2-Stat Signaling Cascade

In a previous study, it was revealed that a GSK-3 inhibitor disturbs the activation of Stat3 by blocking the interaction between IFN-γ and Stat3 in primary astrocytes (18). However, the physiological meaning of a GSK-3 inhibitor-mediated reduction of Stat activity in IFN-γ-stimulated conditions was not defined. Here, we illuminate the precise regulatory mechanism of GSK-3β by examining the influence of a GSK-3β inhibitor on the JAK1/2-Stat signaling axis and PKCδ on the IFN-γ-induced expression of IDO, an immunoregulatory enzyme in DCs. Moreover, by using DC-mediated immune enhancement via T-cell proliferation and a DC-vaccinated murine EG7 thymoma model system, we investigated the physiological role of the GSK-3β inhibition-mediated reduction of IDO via Stat in IFN-γ-treated conditions.

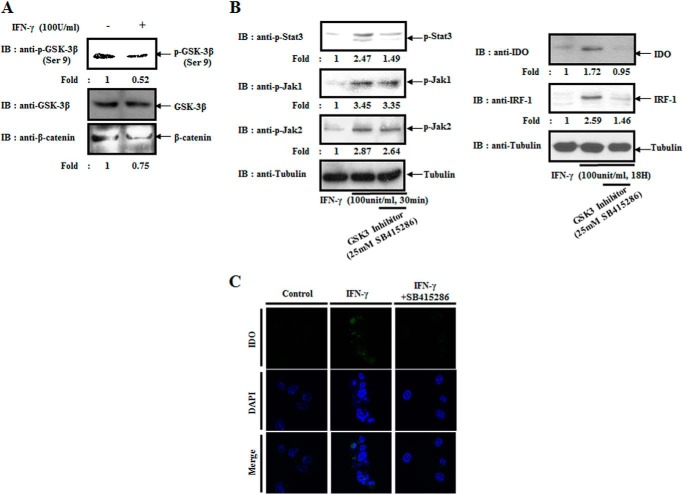

Consistent with a previous study (18), IFN-γ provokes the activation of GSK-3β in BMDCs (Fig. 1A). In addition, in IFN-γ-treated conditions, GSK-3β inhibition blocked the activation of Stat3 (Fig. 1B). However, the activity of JAK1 and JAK2, upstream kinases of Stat3, did not change (Fig. 1B, left panel). Therefore, we inferred that a GSK-3β inhibitor (SB415286) prohibits the JAK1/2-Stat signaling cascade by inhibiting Stat3. In addition, the IFN-γ-mediated expressions of IFN-regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1), a downstream transcription factor of Stat3, and IDO were also inhibited (Fig. 1B, right panel). As shown in Fig. 1C, using an immunofluorescence assay, we confirmed that IFN-γ-induced expression of IDO is reduced by adding a GSK-3β inhibitor. Those results indicate that GSK-3β modulates the expression of IDO, a crucial immunoregulatory protein, by regulating Stat3 in the IFN-γ signaling cascade.

FIGURE 1.

GSK-3β activity is crucial for the expression and activity of IDO via the JAK1/2-Stat signaling cascade. A, BMDCs were treated with or without IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min and harvested. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot (IB) analysis with the indicated antibodies. B, right panel, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor (SB415286) for 30 min and then harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Left panel, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor for 30 min and then harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 24 h. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. C, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor for 30 min and then incubated with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 18 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, stained with rabbit anti-IDO antibodies overnight at 4 °C, and then stained with Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Fluorescence intensity was analyzed using the Zeiss AX10 fluorescence microscope. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

GSK-3β Regulates the Expression of IDO in Both a PKCδ-dependent and -independent Manner

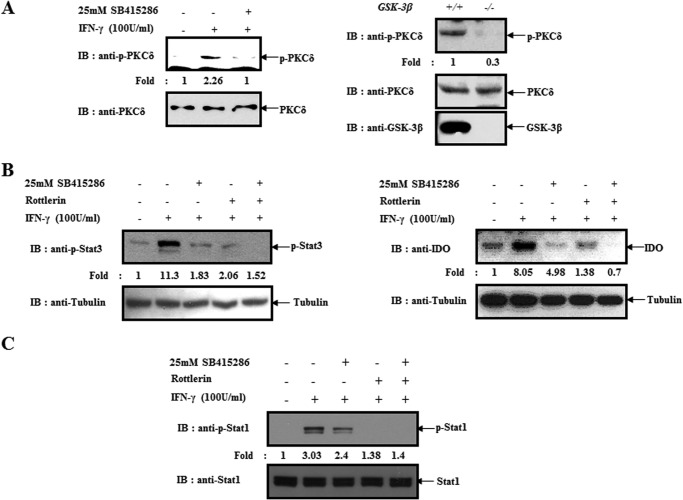

In a previous report, we revealed that PKCδ-dependent Stat regulation was critical for IDO expression in IFN-γ-treated BMDCs (12). Thus, we examined whether or not GSK-3β inhibition-mediated regulation of Stat3 and IDO was via PKCδ. As shown in Fig. 2A, IFN-γ-induced activation of PKCδ was blocked by a GSK-3β inhibitor in BMDCs. Using GSK-3β−/− MEFs, we confirmed that GSK-3β is crucial for PKCδ activity (Fig, 2A, right). Next, we investigated whether or not GSK-3β inhibition-mediated suppression of Stat3 and IDO is independent on PKCδ using rottlerin (PKCδ inhibitor). Here, we found that a GSK-3β inhibitor partially inhibits Stat3 activity and IDO expression in the presence of rottlerin (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

GSK-3β regulates the expression of IDO in a PKCδ-dependent and -independent manner. A, left panel, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor for 30 min and then harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot (IB) analysis with the indicated antibodies. Right panel, GSK-3β +/+ and GSK-3β −/− MEFs were harvested and lysed. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. B, left panel, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor or PKCδ inhibitor (rottlerin) and then harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot analysis with indicated antibodies. Right panel, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor or PKCδ inhibitor and then harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 18 h. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. C, BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3β inhibitor or PKCδ inhibitor incubated with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min and then harvested. Cell lysates were directly subjected to an immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Previously, we found that Stat1 activity is modulated by inhibiting protein kinase Cδ activation in BMDCs (12); therefore, we examined whether GSK-3β activity influences Stat1 activity in IFN-γ-stimulated conditions. Here, we found that GSK-3β inhibition suppressed the activity of Stat1 in a PKCδ-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Thus, we concluded that GSK-3β inhibition-mediated regulation of Stat and IDO occurs via PKCδ-dependent or -independent pathways in IFN-γ-treated BMDCs.

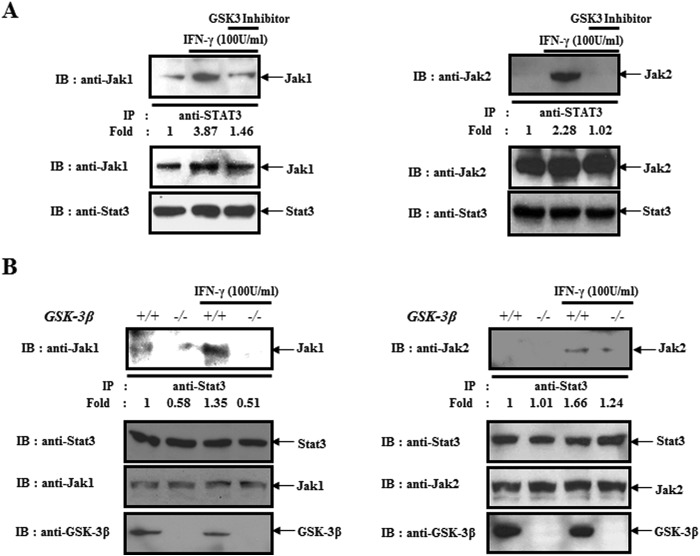

GSK-3β Influences the Interaction between Stat3 and JAK1/2

Next, we examined the PKCδ-independent negative regulation mechanism of Stat3 by GSK-3β inhibition. Thus, we investigated the effect of a GSK-3β inhibitor on the interaction between JAK1/2, upstream kinases of Stat3 and Stat3. We found that IFN-γ-induced interaction of both proteins was blocked by GSK-3β inhibition (Fig. 3A). Using GSK-3β−/− MEFs, we confirmed that GSK-3β contributes to the interaction between Stat3 and JAK1/2 in IFN-γ-treated BMDCs (Fig. 3B). From that data, we found that GSK-3β functions as a positive regulator of IFN-γ-mediated interaction between Stat3 and JAK1/2.

FIGURE 3.

GSK-3β activity contributes to the interaction between Stat3 and JAK1/2. A, coimmunoprecipitation between Stat3 and JAK1/2. BMDCs were pretreated with or without a GSK-3 inhibitor and then harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Stat3 and then were immunoblotted (IB) with an anti-JAK1/2 antibody. B, GSK-3β +/+ and GSK-3β −/− MEFs were harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Stat3 and then were immunoblotted with an anti-JAK1/2 antibody. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

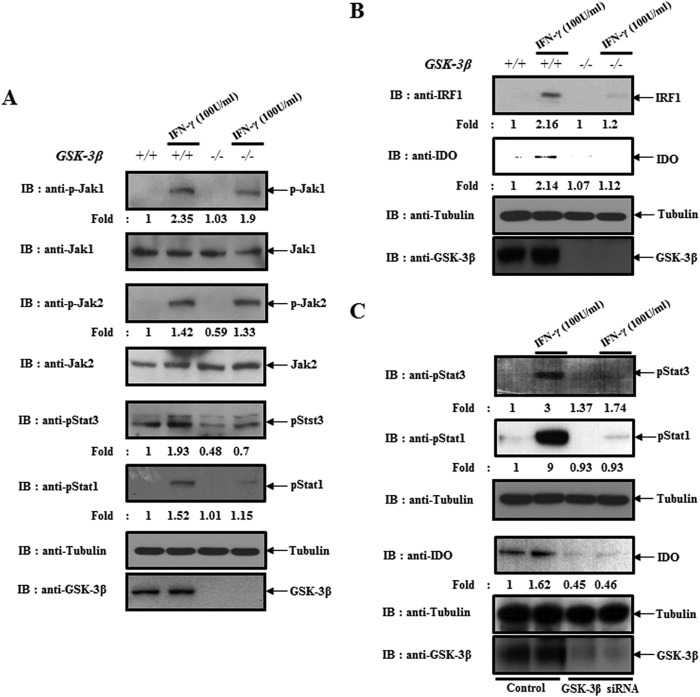

In GSK-3β−/− MEFs and GSK-3β Knockdown Dendritic Cells, the Expressions of IDO and IRF1 Were Blocked Due to Impaired Stat Activity

Because of the fact that we found that GSK-3β regulates the expressions of IDO and IRF1 by modulating Stat in IFN-γ-treated BMDCs, we confirmed the phenomenon using GSK-3β−/− MEFs. Consistent with data in dendritic cells, GSK-3β abolition did not influence the activity of JAK1 and JAK2, upstream kinases of Stat in an IFN-γ-stimulated condition. Instead, it blocked the activation of Stat1 and Stat3 (Fig. 4A). In addition, IFN-γ-mediated expression of IRF-1, a downstream transcription factor of Stat, and IDO were also inhibited (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we confirmed that the activation of Stat1 and Stat3 and the expression of IDO were also inhibited by the silencing of GSK-3β expression (Fig. 4C). From that data, we confirmed that GSK-3β modulates the expression of IDO by regulating Stat in IFN-γ-stimulated conditions.

FIGURE 4.

GSK-3β knock-out or knockdown-mediated impairment of Stat activity blocked the expression of IDO. A, GSK-3β+/+ and GSK-3β−/− MEFs were harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot (IB) analysis with the indicated antibodies. B, GSK-3β+/+ and GSK-3β−/− MEFs were harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 18 h. Cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. C, BMDCs were transfected with GSK-3β siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 h. Cells were harvested after incubating with IFN-γ (100 units/ml) for 30 min (upper panel) or 18 h (lower panel). Cell lysates were directly subjected to an immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

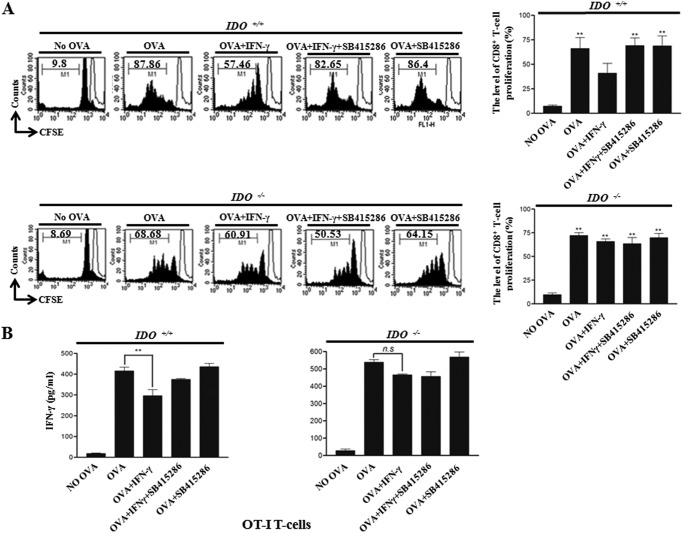

Interferon (IFN)-γ-induced IDO Expression via GSK-3β Activity Plays a Role in CD8+ T Cell Proliferation

To determine whether or not IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity in DCs affects T-cell proliferation, we performed a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay using CD8+ T-cells of OT-I TCR transgenic mice, which express a TCR specific for the MHC class I-restricted OVA peptide 257–264 antigen (OVA(257–264)) in DCs (21). The proliferation of CFSE-labeled OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with OVA(257–264) was significantly higher than that of T-cells co-cultured with unpulsed DCs (Fig. 5A, upper panel). In addition, the enhanced CD8+ T-cell proliferation by DCs pulsed with OVA peptide was dramatically inhibited by treatment with IFN-γ (Fig. 5A, upper panel). Furthermore, IFN-γ-mediated suppressed CD8+ T-cell proliferation was restored by the treatment of a GSK-3β inhibitor (Fig. 5A, upper panel).

FIGURE 5.

IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity is a determinant in CD8+ T-cell proliferation. Immature, OVA (1 μg/ml)-pulsed, OVA-pulsed IFN-γ-treated, and OVA-pulsed IFN-γ + GSK-3β inhibitor-treated IDO+/+ and IDO−/− DCs were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes of OT-I T-cell receptor transgenic mice (1 × 106 per well) for 96 h. A, cells were then harvested and stained with Cy5-labeled anti-CD8 Ab and analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms show CD8+ T-cell proliferation as assessed by flow cytometry. The results are representative of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 compared with No OVA control. B, culture supernatants obtained from the abovementioned condition were harvested after 24 h and were measured, using an ELISA. The mean ± S.E. values represent three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 (n.s, not significant).

Next, to examine whether or not IFN-γ-mediated suppression of CD8+ T-cell proliferation is due to IDO regulated by GSK-3β, we performed an MLR assay using IDO−/− dendritic cells. In that experiment, OVA-pulsed DC-induced CD8+ T-cell proliferation was not suppressed by IFN-γ in the absence of IDO (Fig. 5A, lower panel). We then investigated IFN-γ production in the abovementioned MLR conditions. A higher level of IFN-γ was produced by syngeneic T-cells primed with OVA peptide-pulsed DC reduced by IFN-γ (IDO inducer)-treated DC (Fig. 5B). By using GSK-3β-inhibited DC, IFN-γ-treated DC-mediated attenuation of OVA-pulsed DC-mediated IFN-γ production in T-cells was restored (Fig. 5B). To examine whether the attenuation of OVA-pulsed DC-mediated IFN-γ production in T-cells by IFN-γ-treated DC is due to IDO, we checked the level of IFN-γ in an MLR assay using IDO−/− dendritic cells. Here, the reduced level of OVA-pulsed DC-mediated IFN-γ production in T-cells by IFN-γ-treated DC was not restored (Fig. 5B). From these results, we inferred that IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity in DCs modulates CD8+ T-cell proliferation.

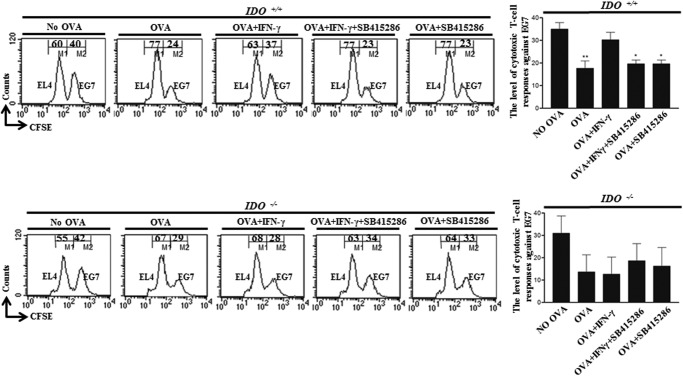

GSK-3β Activity Involving IFN-γ-induced IDO Expression Regulates Cytotoxic T Cell Responses

Next, we investigated the cytotoxic T-cell responses of CD8+ T-cells generated by OVA-pulsed DCs. OVA-pulsed DCs reduced the population of CSFE-stained OVA-expressing EG7 tumor cells compared with nonpulsed DCs, and the reduced OVA-expressing EG7 tumor cells were restored by IFN-γ-treated and OVA-pulsed DCs (Fig. 6, upper panel). Furthermore, the restored CTL activity by IFN-γ was abolished by GSK-3β inhibition (Fig. 6, upper panel). However, DC-mediated modulation of CTL responses did not affect non-OVA-expressing EL4 tumor cells (Fig. 6, upper panel). In addition, by IFN-γ-treated and OVA-pulsed DCs or IFN-γ + SB415286-treated and OVA-pulsed DCs, the modulation of OVA-pulsed DC-mediated CTL activity against OVA-expressing EG7 tumor cells was not observed in the absence of IDO (Fig. 6, lower panel). From that data, we concluded that OVA-specific CTL activity was consistent with the previous CD8+ T-cell proliferation data.

FIGURE 6.

IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity plays a role for cytotoxic T-cell responses. Immature, OVA (1 μg/ml)-pulsed, OVA-pulsed IFN-γ-treated, and OVA-pulsed IFN-γ + GSK-3β inhibitor-treated IDO+/+ and IDO−/− DCs were mixed and cultured with OT-I T-cell receptor transgenic mouse splenocytes (1 × 106 per well) for 72 h and then co-cultured with EL4 (1 × 106, 0.5 μm CFSE-stained (CFSElow)) and EG7 (1 × 106, 10 μm CFSE-stained (CSFEhigh)) cells. After 4 h, the mixed lymphocyte tumor cultures were analyzed by flow cytometry. The mean ± S.E. values represent three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

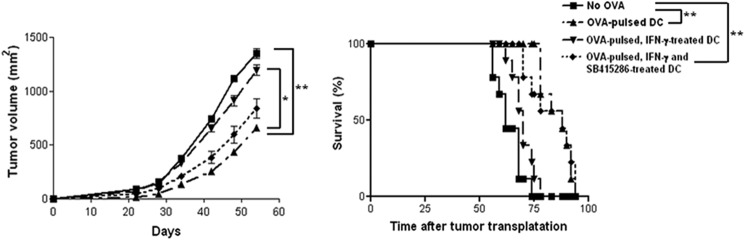

IFN-γ-induced IDO Expression via GSK-3β Is Effective for OVA-pulsed DC Vaccinations against EG7 Thymoma

Next, we assessed that IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β in DCs is crucial for cell-based anti-tumor activity using an EG7 lymphoma model. To determine the anti-tumor potential of immunization with OVA-treated DCs, mice were intraperitoneally injected once a week for 3 weeks with immature DCs, OVA-pulsed DCs, OVA-pulsed IFN-γ-treated DCs, or OVA-pulsed IFN-γ and GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs (1 × 105), followed by subcutaneous injection of EG7 thymoma cells (1 × 106) into the right lower back. Injection of DCs pulsed with OVA(257–264) significantly reduced the size of the OVA-expressing EG7 tumors compared with tumors in mice receiving DCs that had not been pulsed with OVA (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, EG7 tumors in mice that received IFN-γ-treated DCs pulsed with OVA were larger than those in mice that received DCs pulsed with OVA (Fig. 7A). In the group of IFN-γ and GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs pulsed with OVA, the attenuated anti-tumor activity was restored (Fig. 7A). Consistent with that finding, the group of mice injected with OVA-pulsed DCs showed prolongation of survival compared with mice injected with OVA-pulsed IFN-γ-treated DCs (Fig. 7B). The group of mice injected with IFN-γ and GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs pulsed with OVA had an enhanced survival score compared with mice injected with IFN-γ-treated DCs pulsed with OVA (Fig. 7B). From those results, we concluded that IFN-γ-mediated IDO regulation via GSK-3β activity plays a role in dendritic cell-based vaccination against EG7 thymoma tumor.

FIGURE 7.

IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β is effective for OVA-pulsed DC vaccination against EG7 thymoma. Mice were intraperitoneally injected three times (a week apart) with immature DCs, OVA (1 μg/ml)-pulsed, OVA-pulsed IFN-γ-treated, or OVA-pulsed IFN-γ + GSK-3β inhibitor-treated DCs, followed by subcutaneous injection into the right lower back with EG7 thymoma cells (1 × 106). Tumor size was measured every 4 days, and tumor mass was calculated. For statistical analysis, analysis of variance was used. n = 9 mice per group. *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01. Survival of mice was recorded for up to 100 days.

DISCUSSION

It was revealed that GSK-3 is deeply involved in the JAK1/2-Stat signaling cascade (18, 22). However, the physiological meaning of GSK-3-mediated regulation of JAK1/2-Stat signaling has not been defined. Previously, we showed that that PKCδ-dependent Stat regulation is critical for IDO expression in IFN-γ-treated BMDCs (12). Thus, we focused on the physiological role of GSK-3β-mediated regulation of JAK1/2-Stat signaling in the immunomodulatory function of IDO, an immunoregulatory enzyme.

Here, we illuminate the precise regulatory mechanism of GSK-3β by examining the influence of a GSK-3β inhibitor on the JAK1/2-Stat signaling axis and PKCδ on IFN-γ-induced expression of IDO, an immunoregulatory enzyme in DCs. IDO is an essential enzyme that degrades the amino acid tryptophan via the kynurenine pathway (1, 3). It has been reported that IDO is functionally expressed in various immune cells such as DCs and macrophages. It has been shown to also play a role in the immune response as a crucial modulator of tumor-mediated immune tolerance by causing T-cell suppression (1, 23, 24). Based on the function of IDO as a crucial mediator of immune tolerance, we further examined the idea that the DC-based immune response mediated by IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity influences CD8+ T-cell proliferation, cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity, and OVA-pulsed DC vaccination against EG7 thymoma.

DCs function as crucial regulatory cells in the innate and adaptive immune response; therefore, DC-based immunotherapy via the enhancement of host immunogenicity could be a crucial strategy to prevent immune rejection, a major problem in cancer therapy (25, 26). Because of those advantages, anti-tumor immune responses via DC-based vaccination have been utilized in tumor therapy, and vaccination has been studied with regard to the above-mentioned DC functions. Tumor peptide-loaded DCs effectively lead a CTL response in the tumor environment, thereby rendering tumor cell lysis by CTLs. In this study, we applied our finding, the regulation of IFN-γ-induced IDO expression via GSK-3β activity, to DC-based cancer vaccination. We found that the regulation of IDO levels by GSK-3β activity is a determinant for the efficiency of cell-based cancer vaccination using DCs.

Through various experiments, we clarified that GSK-3β activity is crucial for IFN-γ-induced IDO expression in various cells, and we defined that the regulation of DC function by GSK-3β-dependent IDO regulation is important for CD8+ T-cell proliferation and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. Thus, we concluded that GSK-3β activity plays an important role in the immune enhancement-mediated anti-tumor response via IDO regulation.

Further studies are needed to define the pivotal role of the regulation of IDO via GSK-3β in various disease models such as graft-versus-host disease and clinical immune imbalances, including asthma and autoimmune diseases.

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program Grants 2012R1A1A2042924 and 2012R1A2A1A03008433 through National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

- DC

- dendritic cell

- IDO

- indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- GSK-3β

- glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- OVA

- ovalbumin

- CTL

- cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- MLR

- mixed lymphocyte reaction

- TCR

- T-cell receptor

- rm

- recombinant mouse

- BMDC

- bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- CFSE

- carboxyfluroscein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- Ab

- antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mellor A. L., Munn D. H. (2004) IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 762–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banchereau J., Briere F., Caux C., Davoust J., Lebecque S., Liu Y. J., Pulendran B., Palucka K. (2000) Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 767–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Löb S., Königsrainer A., Rammensee H. G., Opelz G., Terness P. (2009) Inhibitors of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase for cancer therapy: can we see the wood for the trees? Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Friberg M., Jennings R., Alsarraj M., Dessureault S., Cantor A., Extermann M., Mellor A. L., Munn D. H., Antonia S. J. (2002) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase contributes to tumor cell evasion of T-cell-mediated rejection. Int. J. Cancer 101, 151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munn D. H., Sharma M. D., Hou D., Baban B., Lee J. R., Antonia S. J., Messina J. L., Chandler P., Koni P. A., Mellor A. L. (2004) Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 280–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uyttenhove C., Pilotte L., Théate I., Stroobant V., Colau D., Parmentier N., Boon T., Van den Eynde B. J. (2003) Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat. Med. 9, 1269–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y., Wang Y., Ogata M., Hashimoto S., Onai N., Matsushima K. (2000) Development of dendritic cells in vitro from murine fetal liver-derived lineage phenotype-negative c-kit(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 95, 138–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayashi T., Beck L., Rossetto C., Gong X., Takikawa O., Takabayashi K., Broide D. H., Carson D. A., Raz E. (2004) Inhibition of experimental asthma by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 270–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takikawa O., Habara-Ohkubo A., Yoshida R. (1990) IFN-γ is the inducer of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in allografted tumor cells undergoing rejection. J. Immunol. 145, 1246–1250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chon S. Y., Hassanain H. H., Gupta S. L. (1996) Cooperative role of interferon regulatory factor 1 and p91 (STAT1) response elements in interferon-γ-inducible expression of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17247–17252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramsauer K., Farlik M., Zupkovitz G., Seiser C., Kröger A., Hauser H., Decker T. (2007) Distinct modes of action applied by transcription factors STAT1 and IRF1 to initiate transcription of the IFN-γ-inducible gbp2 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2849–2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeong Y. I., Kim S. W., Jung I. D., Lee J. S., Chang J. H., Lee C. M., Chun S. H., Yoon M. S., Kim G. T., Ryu S. W., Kim J. S., Shin Y. K., Lee W. S., Shin H. K., Lee J. D., Park Y. M. (2009) Curcumin suppresses the induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by blocking the Janus-activated kinase-protein kinase Cδ-STAT1 signaling pathway in interferon-γ-stimulated murine dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3700–3708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doble B. W., Woodgett J. R. (2003) GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1175–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luo J. (2009) Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) in tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 273, 194–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin M., Rehani K., Jope R. S., Michalek S. M. (2005) Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat. Immunol. 6, 777–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noh K. T., Park Y. M., Cho S. G., Choi E. J. (2011) GSK-3β-induced ASK1 stabilization is crucial in LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 1663–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rodionova E., Conzelmann M., Maraskovsky E., Hess M., Kirsch M., Giese T., Ho A. D., Zöller M., Dreger P., Luft T. (2007) GSK-3 mediates differentiation and activation of proinflammatory dendritic cells. Blood 109, 1584–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beurel E., Jope R. S. (2008) Differential regulation of STAT family members by glycogen synthase kinase-3. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21934–21944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoeflich K. P., Luo J., Rubie E. A., Tsao M. S., Jin O., Woodgett J. R. (2000) Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3β in cell survival and NF-κB activation. Nature 406, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noh K. T., Cho S. G., Choi E. J. (2010) Knockdown of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 modulates basal glycogen synthase kinase-3β kinase activity and regulates cell migration. FEBS Lett. 584, 4097–4101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hogquist K. A., Jameson S. C., Heath W. R., Howard J. L., Bevan M. J., Carbone F. R. (1994) T-cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell 76, 17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin C. F., Tsai C. C., Huang W. C., Wang C. Y., Tseng H. C., Wang Y., Kai J. I., Wang S. W., Cheng Y. L. (2008) IFN-γ synergizes with LPS to induce nitric oxide biosynthesis through glycogen synthase kinase-3-inhibited IL-10. J. Cell Biochem. 105, 746–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Muller A. J., Prendergast G. C. (2007) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in immune suppression and cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 7, 31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Munn D. H., Mellor A. L. (2007) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1147–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferrantini M., Capone I., Belardelli F. (2008) Dendritic cells and cytokines in immune rejection of cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 19, 93–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu Y. J. (2001) Dendritic cell subsets and lineages, and their functions in innate and adaptive immunity. Cell 106, 259–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]