Abstract

Ras-associated autoimmune leukoproliferative disorder (RALD) is a chronic, nonmalignant condition that presents with persistent monocytosis and is often associated with leukocytosis, lymphoproliferation, and autoimmune phenomena. RALD has clinical and laboratory features that overlap with those of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), including identical somatic mutations in KRAS or NRAS genes noted in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Long-term follow-up of these patients suggests that RALD has an indolent clinical course whereas JMML is fatal if left untreated. Immunophenotyping peripheral blood from RALD patients shows characteristic circulating activated monocytes and polyclonal CD10+ B cells. Distinguishing RALD from JMML and CMML has implications for clinical care and prognosis.

Introduction

Ras-associated autoimmune leukoproliferative disorder (RALD) is a nonmalignant clinical syndrome initially identified in a subset of putative autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) patients.1 Similar to patients with ALPS, RALD patients present with lymphadenopathy, massive splenomegaly, increased circulating B cells, hypergammaglobulinemia, and autoimmunity.1-3 In contrast to ALPS, biomarkers such as CD4–/CD8– double negative T-cell receptor αβ (TCRαβ+) T cells and serum vitamin B12 levels are not always increased, and germline or somatic mutations in FAS, FASL, or CASP10 are absent in RALD. Persistent absolute or relative monocytosis is a cardinal feature of RALD. Bone marrow and peripheral blood smear findings overlap with those of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) in children or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) in older patients. Activating somatic mutations that cause amino acid substitutions that affect codons 12 or 13 in KRAS or NRAS were identified in myeloid and lymphoid lineages.2 In 2009, the revised classification and nomenclature of RALD was adopted to distinguish it from ALPS.4

JMML is an aggressive malignant hematopoietic neoplasm of childhood with myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative features. Patients present with splenomegaly, fever, thrombocytopenia, monocytosis, and excess myelomonocytic cells that infiltrate skin and vital organs. JMML accounts for 20% to 30% of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative disorders in the pediatric population.5 The prognosis for JMML is poor with median survival of 1 year for untreated patients. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has become the standard of care for JMML.6,7 CMML has a variable course in adults and often requires chemotherapy.

RAS

RAS genes (named for their role in forming rat sarcomas) were first recognized 50 years ago in tumor-initiating retroviruses (eg, Harvey sarcoma virus, Kirsten sarcoma virus, and Rasheed sarcoma virus), and their cellular homologs are implicated in myeloproliferative neoplasms8 and are found mutated in almost 30% of human cancers.9,10 How RAS proteins contribute to neoplasia and lymphoproliferative disorders remains to be fully elucidated.9,10 The RAS signaling proteins are ubiquitously expressed in all cells and serve as small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) that play diverse roles in cell cycle progression, proliferation, apoptosis, and cytoskeletal motility. In the immune system, they control B-cell tolerance and production of autoantibodies.11 Germline RAS mutations have been identified in nonmalignant conditions, including 5 neurodevelopmental dysmorphic syndromes termed “RASopathies” that carry an increased risk of autoimmunity and malignancy.12-14

Remarkably, the identical KRAS or NRAS mutations found in all RALD patients are also reported in up to 25% of JMML patients,15 suggesting a shared molecular etiology. Amino acid substitutions in codons 12 and 13 of KRAS or NRAS noted in our cohort of patients (Figure 1A) result in constitutive binding of GTP and activation of the NRAS or KRAS proteins thereby inducing the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Increased signaling causes proliferation and downregulation of the proapoptotic protein Bim,1 resulting in attenuation of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. In vitro studies of T cells from RALD showed partial resistance to interleukin-2 withdrawal-induced apoptosis but sensitivity to other intrinsic apoptotic pathway stimuli. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors, which block the function of RAS, restored Bim levels and apoptosis in T cells from RALD patients.1,2

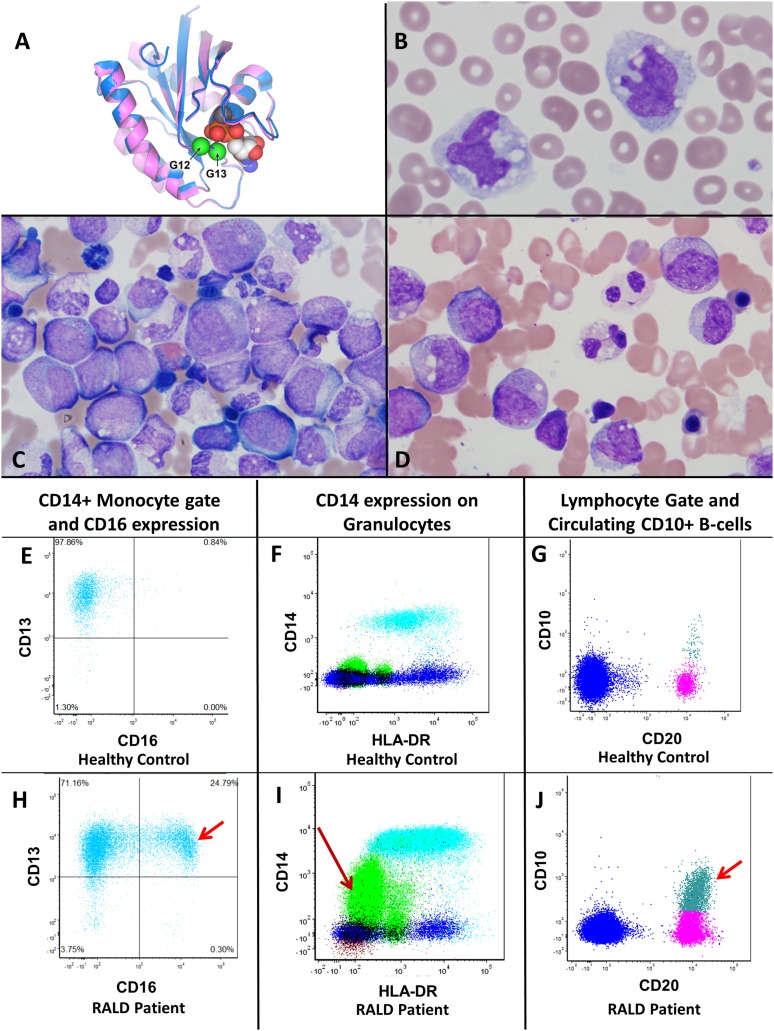

Figure 1.

(A) Simplified depiction of Ras protein with sites of mutation noted in Table 1. Combined structures of KRAS (blue) and NRAS (magenta). The mutation on the right (closest to bound guanosine diphosphate [GDP]) is G13, and G12 is on the left (farthest from bound GDP). (B) Peripheral blood monocytes from 8-year-old RALD patient 381.1 with leukocytosis, monocytosis, and lymphocytosis (×1000). (C) Bone marrow aspirate from same patient showing granulocytic hyperplasia with mild-to-moderate left shift in myeloid maturation with less than 5% blasts (×500). (D) Bone marrow from patient 104.1 showing pelgeroid granulocytes and left shift. (E) Healthy control peripheral blood (PB) with normal circulating monocytes that are CD16–. (F) Healthy control PB showing that only monocytes (turquoise) are positive for CD14 and granulocytes (green population) are negative for CD14. (G) Healthy control PB lymphocyte gate demonstrating that CD20+ B cells are largely CD10–. (H) PB CD14+ monocyte gate showing increased expression of CD16 on monocytes in RALD in comparison with monocytes from healthy control (E). (I) Prominent increased expression of CD14 on granulocytes (green) in RALD which is not seen in healthy controls (F). (J) Peripheral blood lymphocyte gate with B-cell lymphocytosis (polyclonal) with marked increase in CD10+ circulating late precursor B cells in comparison with healthy control (G).

Although both RALD and JMML share common RAS mutations, JMML cells apparently accumulate additional genetic abnormalities that contribute to the malignant phenotype. These include cytogenetic abnormalities and activating somatic mutations in PTPN11, c-CBL, ASXL1, and FLT-3.16-20 Additionally, germline mutations in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) syndrome lead to a high risk of developing JMML in the first decade of life.16 NF1 encodes neurofibromin, which functions as a GTPase-activating protein that regulates the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway.21 Noonan syndrome is also one of the so-called RASopathies characterized by germline mutations in genes involved in the RAS pathway, including PTPN11,22 KRAS, RAF1, and NRAS, resulting in an increased risk of developing JMML.14 On the basis of recent molecular analyses, more than 90% of JMML patients were found to harbor somatic mutations in NRAS, KRAS, NF1, PTPN11, and CBL, all of which are thought to act as driver mutations in the RAS signaling pathway.6,16 Somatic mutations in PTPN11 are indeed the most commonly identified mutations found in up to 35% of patients with JMML.17,22 Whole-exome sequencing has led to the detection of secondary mutations involving SETBP1 and JAK3 in 17% of JMML patients.23

The current accepted diagnostic criteria for JMML24,25 have been revised from the World Health Organization 2008 recommendations. Category 1 criteria (all of the following should be met) include persistent monocytosis with more than 1000 monocytes per microliter (1 × 109/L) in the peripheral blood, splenomegaly, less than 20% blasts in the bone marrow and/or peripheral blood, and absence of the t(9;22) BCR-ABL translocation. Category 2 criteria (at least 1 of the following conditions must be met) include somatic mutation in RAS or PTPN11, clinical diagnosis of NF1 or NF1 gene mutation, homozygous mutation in CBL, or monosomy 7. Category 3 criteria (at least 2 of the following must be met if category 2 criteria are not satisfied) include circulating myeloid precursors, white blood cell (WBC) count of more than 10 000/μL (10 × 109/L), increased hemoglobin F for age, clonal cytogenetic abnormality excluding monosomy 7, and granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor hypersensitivity of myeloid progenitors in vitro. Of note, 7% to 10% of JMML patients may not have splenomegaly at presentation; if the remaining category 1 criteria are met, in addition to 1 of category 2 criteria or 2 of category 3 criteria, a diagnosis of JMML may be made.

Nearly all the RALD patients in our cohort technically meet the revised diagnostic criteria for JMML. It is yet to be established whether RALD is a nonmalignant disease, a premalignant condition, or a clonal indolent malignancy of childhood. On the basis of our data and the indolent clinical course, our group hypothesizes that RALD is a nonmalignant disease with the potential for malignant transformation in rare individual cases. Lanzarotti et al26 reported 1 RALD patient who progressed to severe JMML after 10 years of indolent disease. Conversely, per published reports, some JMML patients have an indolent clinical course with spontaneous resolution of disease, especially those with NRAS mutations.27,28 Thus, discrimination of these disorders early in life can be challenging. Additionally, RALD may be underappreciated as a disease in the differential diagnosis of patients with splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and monocytosis. The key clinical and laboratory features of RALD have not been previously elucidated in a large group of patients and are presented here.

Clinical spectrum of RALD

The clinical spectrum of 13 RALD patients with a median follow up of 9 years (range, 4-56 years) at our institution is outlined in Table 1. All patients included here underwent informed consent process. All of the patients presented with persistent relative or absolute monocytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia, B lymphocytosis, and splenomegaly. Only 3 patients underwent splenectomy to attain relief from hypersplenism and pain as a result of splenic ischemia and necrosis. Some had increased hemoglobin F for age and mildly elevated serum vitamin B12 levels (median, 1029 pg/mL; range, 1029-4548 pg/mL; normal, 193-982 pg/mL). Early in life and in adolescence, leukocytosis of more than 10 000 cells per microliter is common, often with a notable mild left shift and circulating immature granulocytes and monocytes. Circulating blasts or nucleated red blood cells are rare in RALD. Granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor hypersensitivity of myeloid progenitors was positive in 3 of 5 RALD patients tested.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory features of RALD patients

| Patient | Gender | Age, y | Age of onset, y | RAS mutations | Absolute monocyte count (1000/μL) | CD20+ absolute counts | IgG (mg/dL) | Direct antiglobulin test | Lupus anticoagulant | Other autoantibodies | Flow cytometry monocyte subpopulations | Flow cytometry granulocyte subpopulations | Flow cytometry CD10+ circulating B cells | Cyto-genetic analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104.1 | F | 20 | 1 | KRAS c.38 G>A; p.G13D | 49.4 | 53 | 2450 | Positive | Negative | ACA, ANA | CD16+ | CD14+ (pelgeroid morphology) | No | Normal |

| 381.1 | F | 10 | 4 | KRAS c.37 G>T; p.G13C | 2.1 | 559 | 1410 | Positive | Positive | ANA | CD16+ | CD14+ (pelgeroid morphology) | Yes | Normal |

| 85.1*† | F | 13 | 4 | KRAS c.37 G>T; p.G13C | 1.5 | 642 | 2130 | Negative | N.D. | ACA, anti-neutrophil, anti-platelet | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 337.1 | F | 12 | 5 | KRAS c.38 G>A; p.G12D | 1.9 | 497 | 2220 | Negative | Positive | ACA, ANA | CD16+ | CD14+ | Yes | Normal |

| 380.1 | F | 41 | 36 | KRAS c.35 G>C; p.G12A | 10 | 1799 | 1430 | Positive | Positive | ANA | CD16+, CD56+, CD10+ | CD14+ | Yes | Normal |

| 379.1 | M | 13 | 3 | KRAS c.34 G>A; p.G12S | 1.8 | 452 | 1610 | Positive | Negative | ACA, ANA | No atypia | CD14+ | No | Normal |

| 411.1† | F | 12 | 2 | KRAS c.37 G>T; p.G13C | 1.5 | 2466 | 1370 | Positive | Positive | Negative | CD16+ | CD14+ | No | N.D. |

| 336.1 | M | 5 | 0.25 | NRAS c.35G>T; p.G12V | 14.3 | 2541 | 1570 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | CD13– | No atypia | Yes | N.D. |

| 260.1 | M | 6 | 0.25 | NRAS c.38 G>A; p.G13D | 4.8 | 3527 | 2100 | Positive | Negative | ACA, ANA | CD16+ | CD14+ | Yes | Normal |

| 265.1 | M | 9 | 0.25 | NRAS c.38 G>A; p.G13D | 2.1 | 425 | 2750 | Positive | Positive | Glomerulonephritis | CD16+ | No atypia | Yes | Normal |

| 58.1 | M | 57 | 0.5 | NRAS c.38 G>A; p.G13D | 3.7 | 4301 | 1310 | Positive | Positive | ACA | CD16+ | No atypia | Yes | Normal |

| 163.1 | M | 19 | 2 | NRAS c.38 G>A; p.G13D | 3.7 | 743 | 2190 | Positive | Positive | ACA, ANA | CD16+ | No atypia | No | N.D. |

| 406.1 | M | 5 | 0.75 | NRAS c.34GA; p. G12S | 4.2 | N.D. | 1030 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

Peripheral blood reference ranges (adult): absolute monocyte count 0.30 to 0.82 1000 cells per microliter; absolute CD20+ count 59 to 329 cells per microliter; serum immunoglobulin G (IgG), 572 to 1474 mg/dL.

ACA, anticardiolipin antibodies (positive: ACA IgG 18 to 80 IgG phospholipid units and ACA IgM >16 IgM phospholipid units); ANA, antinuclear antibodies (normal, 0 to 0.9 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units); F, female; M, male; N.D., not determined.

Deceased, no infectious or malignant neoplastic disease noted at autopsy.

Pericarditis.

Six patients had somatic mutations in NRAS and 7 had somatic mutations in KRAS. Twelve of 13 patients had disease onset as children; the male-to-female ratio was 7:6. Of note, 6 patients presented within the first year of life (5 with KRAS mutations and 1 with an NRAS mutation). To date, evolution to myeloid malignancy has not occurred in any of the 13 patients. The oldest adult male in our cohort (currently 57 years old) presented at 0.5 years of age, reportedly with acute leukemia (not subclassified), which resolved following treatment with oral medications for a few years. At age 38, he developed a peripheral B-cell lymphoma, was successfully treated, and continues to have persistent leukocytosis with neutrophilia, monocytosis, and lymphocytosis. Another pediatric patient (a 13-year-old female) died of undetermined cause, but pericardial effusion and inflammation may have played a role; autopsy ruled out a malignant cause of death. Of note, 2 patients have developed pericardial effusions (Table 1), which may be indicative of the autoimmune or autoinflammatory manifestation of the disease.

Immunophenotypic and morphologic features of monocytes, granulocytes, and lymphocytes in RALD

Detection of abnormal antigen expression on neoplastic monocytes and granulocytes by flow cytometry has been described in myelodysplastic syndromes and can help distinguish reactive nonmalignant cells from their neoplastic counterparts.29,30 Dysplastic monocytes may show aberrant or abnormal higher expression of surface proteins, including CD56, CD16, CD7, CD2, or CD5 and downregulated or decreased expression of CD14, CD64, CD33, CD13, CD11b, or CD11c. Dysplastic granulocytes often show decreased side-light scatter associated with hypogranularity; aberrant maturation patterns based on expression of CD13, CD16, and CD11b; abnormal expression of CD2, CD7, CD5, or CD56; increased expression of CD117, HLA-DR, or CD36; or decreased expression of CD64 or CD33. Presence of monocytosis with more than 3 immunophenotypic aberrations favors a neoplastic or clonal process over a reactive monocytosis.30 Although aberrant immunophenotypic features of monocytes and granulocytes have been described in myelodysplastic processes, including JMML and CMML, similar studies in RALD were lacking. We performed peripheral blood flow cytometry in 11 of 13 patients diagnosed with RALD (Table 1 and supplemental Table, available on the Blood Web site) by using methods previously described.31

Peripheral blood monocytes

Median absolute monocyte count was 2700 cells per microliter (range, 1500-9910 cells per microliter), with monocytes being 26% of the WBC (range, 9.5%-52%). Large predominantly mature monocytes with cytoplasmic vacuoles were seen in the majority of peripheral blood smears (Figure 1B) with occasional circulating immature monocytes in 3 patients. In contrast to healthy controls (Figure 1E), 9 (82%) of 11 RALD patients had a prominent subset of circulating monocytes with increased expression of CD16 (Fcγ receptor 3A) (Figure 1H) detected by flow cytometry. Within this group, the average percentage of monocytes expressing CD16 was 21% (range, 13%-34%).

At least 1 example of abnormal surface antigen expression was seen in 2 of 11 of RALD patients studied, including CD56 expression on monocytes in 1 of 11 (supplemental Figure F vs B), decreased CD13 expression in 1 of 11 (supplemental Figure G vs C), and atypical expression of CD10 in 1 of 11 (supplemental Figure H vs G). No patients showed decreased expression of CD11c or abnormal expression of CD7, CD5, or CD2 on monocytes.

Peripheral blood granulocytes

The average WBC count was 10 200 cells per microliter (range, 2900-25 400 cells per microliter; standard deviation, 7.16), and the average absolute neutrophil count was 4100 cells per microliter (range, 560-11 200 cells per microliter; standard deviation, 3.4). Three pediatric patients had neutropenia (<1300 cells per microliter). Both adult patients had neutrophilia (>8000 cells per microliter). Atypical expression of CD14 on granulocytes was the most common finding and was detected in 7 (64%) of 11 patients (Figure 1I vs F). Pelgeroid granulocytes were seen on the peripheral blood smears of 2 patients. None of the RALD patients had circulating blasts greater than 0.5%.

Peripheral blood lymphocytes.

The average absolute lymphocyte count was 2790 cells per microliter (range, 642-5900 cells per microliter). B-cell lymphocytosis was common with an average absolute B-cell count of 990 cells per microliter (range, 530-2450 cells per microliter) with an average of 26.9% B cells (range, 3.5%-54.7%) in the lymphocyte gate. These B cells were polyclonal. Increased circulating CD10+ late precursor B cells (Figure 1J vs G) were detected in 7 (64%) of 11 of the RALD patients. Fewer than 3 atypical immunophenotypic changes by flow cytometric analysis were seen in 10 (91%) of 11 patients. Only 1 patient showed 3 atypical immunophenotypic changes (patient 380.1) of uncertain significance, including the presence of a CD56+ subpopulation of monocytes, a CD10+ subpopulation of monocytes, and CD14+ granulocytes. All but 1 patient had modestly elevated double-negative T cells (CD3+TCRαβ+ and CD4–CD8– double negative). The median was 66 cells per microliter (1.8%; range, 6-288 cells per microliter [0.5%-7.6%]); the normal level is 6 to 23 cells per microliter (<1.5% of total lymphocytes).

Bone marrow features.

Bone marrow specimens were available for review in 9 of 13 patients. Overall, marrows were hypercellular for age with trilineage hematopoiesis and mild-to-moderate left shift in myeloid maturation (Figure 1C) with less than 5% blasts. Pelgeroid neutrophils were seen in 2 bone marrow specimens (Figure 1D). Overtly dysplastic features in more than 10% of myeloid, monocytic, megakaryocytic, and/or erythroid lineages were not definitively identified. Cytogenetic analyses of marrow aspirates revealed a normal karyotype.

Discussion and spectrum of disease

The presence of RAS mutations in the hematopoietic lineages of patients with RALD suggests that RALD is a somatic disorder likely arising in an early precursor or hematopoietic stem cell leading to myelomonocytic and lymphoid hyperplasia with some features resembling JMML and/or CMML. Cryopreserved umbilical cord blood was available for testing in 1 patient (patient 381.1) and showed no KRAS mutation, which suggests that the somatic genetic defect develops after birth. Atypical immunophenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes and granulocytes are detected in RALD. Increased CD16 expression on monocytes suggests that the monocytic population comprises increased nonclassical32 or activated monocytes that have features of tissue macrophages,33 cells that are also increased in sepsis and inflammation.32,34 Polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis with circulating CD10+ B cells and increased CD14 expression on granulocytes are also common in RALD. Although these immunophenotypic changes are characteristic for RALD, we do not know the diagnostic specificity because a detailed comparison of the monocyte immunophenotype in JMML and/or CMML has not been performed.

Current revised diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of JMML are suboptimal because these criteria are unable to distinguish JMML with a normal karyotype (a malignant condition) from RALD (an indolent condition). Given that RALD and its clinical overlap with JMML are likely underrecognized, some patients diagnosed with JMML may have an indolent disease more consistent with RALD. JMML patients have occasionally been reported to undergo spontaneous regression of proliferative myelomonocytic disease27,35-37 with persistence of autoimmune disease, B lymphocytosis, and RAS-mutated clones.35 RAS activation can indeed alter selection patterns of autoreactive B cells and antibody production leading to autoimmune manifestations.11 Others have reported long-term survival of JMML patients without the need for chemotherapy treatment or bone marrow transplant, and relief of symptoms by using immunosuppressive agents such as sirolimus, suggesting indolent autoinflammatory disease.27,35-38 Niemeyer et al39 reported that 65% of JMML patients had hypergammaglobulinemia, and 22% had signs of autoimmunity, which are also features of RALD. Interestingly, although PTPN11 mutations result in constitutive activation of the RAS signaling pathway and are common in JMML17,22 and Noonan syndrome, so far we have not identified PTPN11 mutations in any of the patients being evaluated for RALD. This may be related to the fact that PTPN11 mutations confer a more aggressive phenotype and rapidly fatal disease in JMML14 in contrast to the indolent clinical course associated with RALD.

We view RALD and JMML as related diseases within a broad spectrum. Both share underlying RAS mutations and myeloproliferation. However, additional genetic alterations are likely obligatory for progression to JMML. Notably, 1 RALD patient developed an aggressive clinical phenotype suggestive of JMML 10 years after RALD diagnosis.26 The most definitive diagnostic distinction between RALD and JMML occurs in the setting of a cytogenetic abnormality (eg, monosomy 7), which excludes RALD and favors a malignant process. All 9 patients tested in our RALD cohort had karyotypically normal bone marrow. However, normal bone marrow cytogenetics is also reported in approximately 65% of JMML patients.39 Morphologic evidence of dysplasia, if present, is considered a helpful diagnostic feature in JMML and/or CMML. However, morphologic features compatible with dysplasia, such as hyposegmented pelgeroid neutrophils, can also be seen in RALD (Figure 1), further obscuring the distinction. Consensus diagnostic guidelines are critical for distinguishing RALD from JMML in the setting of a normal karyotype in order to guide appropriate therapy. On the basis of the indolent nature of the disease, we would recommend very close clinical monitoring for malignant transformation and/or acquisition of additional dysplastic, molecular, or clonal karyotypic abnormalties in RALD. We recommend avoiding aggressive interventions such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantations in RALD patients without clear evidence of malignancy. Further collaborative investigations with integration of clinical and laboratory studies, long-term follow-up, and exploration of targeted therapeutics in modulating RAS pathway dysfunction in larger cohorts is imperative to distinguish RALD from JMML and to optimize patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and their parents for participating in this study as well as referring physicians and the patients’ local caregivers for sharing their clinical records, including Drs Yoav Messinger, Erick Werner, Mustafa Barbour, Michael Recht, Donald Mahoney, and Marc Natter. The authors also thank Matt Biancalana for generating the image of the Ras protein structure in Figure 1, Dr Diane Arthur for cytogenetics laboratory support, Joie Davis and Morgan Butrick for providing genetic counseling, Dr Mignon Loh for providing granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor hypersensitivity testing and RAS mutation analysis in 5 patients.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: K.R.C., V.K.R., M.L., and T.A.F. designed the research; S.P., V.K.R., and K.R.C. collected data; K.R.C., S.P., V.K.R., R.C.B., J.B.O., T.A.F., and M.L. analyzed and interpreted the data; K.R.C., V.K.R., and M.L. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: V. Koneti Rao, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Drive, Building 10, Room 12C106, MSC-1899, Bethesda, MD 20892-1899; e-mail: koneti@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Oliveira JB, Bidère N, Niemela JE, et al. NRAS mutation causes a human autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(21):8953–8958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niemela JE, Lu L, Fleisher TA, et al. Somatic KRAS mutations associated with a human nonmalignant syndrome of autoimmunity and abnormal leukocyte homeostasis. Blood. 2011;117(10):2883–2886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takagi M, Shinoda K, Piao J, et al. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome-like disease with somatic KRAS mutation. Blood. 2011;117(10):2887–2890. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-301515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira JB, Bleesing JJ, Dianzani U, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria and classification for the autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS): report from the 2009 NIH International Workshop. Blood. 2010;116(14):e35–e40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luna-Fineman S, Shannon KM, Atwater SK, et al. Myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative disorders of childhood: a study of 167 patients. Blood. 1999;93(2):459–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang TY, Dvorak CC, Loh ML. Bedside to bench in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: insights into leukemogenesis from a rare pediatric leukemia. Blood. 2014;124(16):2487–2497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-300319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Locatelli F, Niemeyer CM. How I treat juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(7):1083–1090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-550483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Etten RA, Shannon KM. Focus on myeloproliferative diseases and myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(6):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, McCormick F. Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teodorovic LS, Babolin C, Rowland SL, et al. Activation of Ras overcomes B-cell tolerance to promote differentiation of autoreactive B cells and production of autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(27):E2797–E2806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402159111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierpont ME, Magoulas PL, Adi S, et al. Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1149–e1162. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cizmarova M, Kostalova L, Pribilincova Z, et al. Rasopathies - dysmorphic syndromes with short stature and risk of malignancy. Endocr Regul. 2013;47(4):217–222. doi: 10.4149/endo_2013_04_217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niemeyer CM. RAS diseases in children. Haematologica. 2014;99(11):1653–1662. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.114595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyauchi J, Asada M, Sasaki M, Tsunematsu Y, Kojima S, Mizutani S. Mutations of the N-ras gene in juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1994;83(8):2248–2254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niemeyer CM, Kratz CP. Paediatric myelodysplastic syndromes and juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia: molecular classification and treatment options. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(6):610–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loh ML, Vattikuti S, Schubbert S, et al. Mutations in PTPN11 implicate the SHP-2 phosphatase in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2004;103(6):2325–2331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loh ML, Sakai DS, Flotho C, et al. Mutations in CBL occur frequently in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(9):1859–1863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugimoto Y, Muramatsu H, Makishima H, et al. Spectrum of molecular defects in juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia includes ASXL1 mutations. Br J Haematol. 2010;150(1):83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gratias EJ, Liu YL, Meleth S, Castleberry RP, Emanuel PD. Activating FLT3 mutations are rare in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(2):142–146. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu GF, Lin B, Tanaka K, et al. The catalytic domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product stimulates ras GTPase and complements ira mutants of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990;63(4):835–841. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tartaglia M, Kalidas K, Shaw A, et al. PTPN11 mutations in Noonan syndrome: molecular spectrum, genotype-phenotype correlation, and phenotypic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70(6):1555–1563. doi: 10.1086/340847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakaguchi H, Okuno Y, Muramatsu H, et al. Exome sequencing identifies secondary mutations of SETBP1 and JAK3 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(8):937–941. doi: 10.1038/ng.2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan RJ, Cooper T, Kratz CP, Weiss B, Loh ML. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a report from the 2nd International JMML Symposium. Leuk Res. 2009;33(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dvorak CC, Loh ML. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: molecular pathogenesis informs current approaches to therapy and hematopoietic cell transplantation. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:25. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanzarotti N, Bruneau J, Trinquand A, et al. RAS-associated lymphoproliferative disease evolves into severe juvenile myelo-monocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123(12):1960–1963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-548958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuda K, Shimada A, Yoshida N, et al. Spontaneous improvement of hematologic abnormalities in patients having juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia with specific RAS mutations. Blood. 2007;109(12):5477–5480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doisaki S, Muramatsu H, Shimada A, et al. Somatic mosaicism for oncogenic NRAS mutations in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(7):1485–1488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-406090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kussick SJ, Fromm JR, Rossini A, et al. Four-color flow cytometry shows strong concordance with bone marrow morphology and cytogenetics in the evaluation for myelodysplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124(2):170–181. doi: 10.1309/6PBP-78G4-FBA1-FDG6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westers TM, Ireland R, Kern W, et al. Standardization of flow cytometry in myelodysplastic syndromes: a report from an international consortium and the European LeukemiaNet Working Group. Leukemia. 2012;26(7):1730–1741. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganapathi KA, Townsley DM, Hsu AP, et al. GATA2 deficiency-associated bone marrow disorder differs from idiopathic aplastic anemia. Blood. 2015;125(1):56–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-580340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116(16):e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Fingerle G, Ströbel M, et al. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes exhibits features of tissue macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(9):2053–2058. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fingerle G, Pforte A, Passlick B, Blumenstein M, Ströbel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients. Blood. 1993;82(10):3170–3176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takagi M, Piao J, Lin L, et al. Autoimmunity and persistent RAS-mutated clones long after the spontaneous regression of JMML. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1926–1928. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maschan M, Bobrynina V, Khachatryan L, et al. Control of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura by sirolimus in a child with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and somatic N-RAS mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(10):1871–1873. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maschan AA, Khachatrian LA, Solopova GG, et al. Development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a patient in very long lasting complete remission of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(1):e32–e34. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181f46e3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuda K, Yoshida N, Miura S, et al. Long-term haematological improvement after non-intensive or no chemotherapy in juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia and poor correlation with adult myelodysplasia spliceosome-related mutations. Br J Haematol. 2012;157(5):647–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niemeyer CM, Arico M, Basso G, et al. European Working Group on Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Childhood (EWOG-MDS) Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in childhood: a retrospective analysis of 110 cases. Blood. 1997;89(10):3534–3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]