Key Points

NOTCH1 inhibits apoptosis via HES1-mediated repression of BBC3 in T-ALL.

Perhexiline, a HES1 signature modulator drug, has strong antileukemic effects in vitro and in vivo.

Abstract

Oncogenic activation of NOTCH1 signaling plays a central role in the pathogenesis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with mutations on this signaling pathway affecting more than 60% of patients at diagnosis. However, the transcriptional regulatory circuitries driving T-cell transformation downstream of NOTCH1 remain incompletely understood. Here we identify Hairy and Enhancer of Split 1 (HES1), a transcriptional repressor controlled by NOTCH1, as a critical mediator of NOTCH1-induced leukemogenesis strictly required for tumor cell survival. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that HES1 directly downregulates the expression of BBC3, the gene encoding the PUMA BH3-only proapoptotic factor in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Finally, we identify perhexiline, a small-molecule inhibitor of mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1, as a HES1-signature antagonist drug with robust antileukemic activity against NOTCH1-induced leukemias in vitro and in vivo.

Introduction

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias (T-ALLs) are highly aggressive hematologic tumors derived from the malignant transformation of immature T-cell progenitors.1 T-ALL results from a multistep process involving the activation of oncogenes and loss of tumor suppressor genes, which disrupts specific mechanisms regulating proliferation, differentiation, and survival during T-cell development.1 In this setting, the identification of activating mutations in the NOTCH1 gene in more than 60% of T-ALLs highlights the central role of aberrant NOTCH signaling in the pathogenesis of this disease.2 Constitutive activation of mutant NOTCH1 in T-ALL drives a transcriptional program promoting leukemia cell growth and proliferation via multiple direct and indirect mechanisms including, most prominently, transcriptional activation of the MYC oncogene and upregulation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway.3 In this circuitry, Hairy and Enhancer of Split 1 (HES1), a basic helix-loop-helix transcriptional regulator directly controlled by NOTCH1, functions as a critical factor mediating transcriptional repression downstream of NOTCH signaling.4

An important role for Hes1 in T-cell development was first realized in Hes1 knockout mice, which show a rudimentary or complete absence of thymic development.5 Consistently, conditional deletion of Hes1 in hematopoietic progenitors impaired T-cell development by compromising the capacity of early lymphoid progenitors to seed and populate the thymus.6 In T-ALL, the NOTCH1-HES1 regulatory axis is implicated in the upregulation of PI3K7 and NFKB signaling.8 Consistently, Hes1 is required for NOTCH1-induced transformation and for leukemia cell survival.6 However, the specific roles and mechanisms of HES1 in NOTCH1-induced leukemia remain incompletely understood.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

HEK-293T, CUTLL1, CCRF-CEM, JURKAT, RPMI 8402, DND41, MOLT4, LOUCY, MOLT16, KE37, and HPB-ALL cells were cultured in standard conditions in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HEK-239T cells, CCRF-CEM, JURKAT, and RPMI 8402 were from ATCC, and DND41 and HPB-ALL were from DSMZ. The CUTLL1 cell line generated in our laboratory has been previously described.9 Mouse primary tumors were cultured in vitro with OP9 stromal cells in OPTIMEM-Glutamax medium supplemented with mouse IL7 (10 ng/mL), β-mercaptoethanol (55 μM), 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 2 weeks and then removed from the coculture system for subsequent experiments.

Patient samples

T-ALL samples were provided by Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, the University of Padova, and the Hospital Central de Asturias with informed consent and analyzed under the supervision of the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board committee. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Primary T-ALL cells were cultured in vitro with MS5-DL1 stromal cells in MEM-α and in the presence of GlutaMAX, insulin, human serum, interleukin 7, stem cell factor, and Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand.10 All cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere under 5% CO2.

Drugs

Both 4-hydroxytamoxifen (CAS 68047-06-3) and perhexiline (CAS 6724-53-4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Chromatic immunoprecipitation

We performed chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) using the Agilent Mammalian ChIP-on-chip ChIP protocol, as described elsewhere.11 A detailed description of ChIP procedures is included in the supplemental Materials and methods available on the Blood Web site.

Mice and animal procedures

All animals were maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities at the Irving Cancer Research Center on the Columbia University Medical Campus. Animal procedures were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To generate conditional inducible Hes1 knockout mice, we bred Hes1 conditional knockout mice (Hes1f/f)12 with ROSA26Cre-ERT2/+ mice, which express a tamoxifen-inducible form of the Cre recombinase from the ubiquitous Rosa26 locus.13 To generate NOTCH1-induced T-ALL tumors in mice, we performed retroviral transduction of bone marrow cells enriched in lineage-negative cells, using magnetic beads (lineage cell depletion kit by Miltenyi, kit 130-090-858, following manufacturer’s guidelines) with an activated form of the NOTCH1 oncogene (ΔE-NOTCH1), and transplanted them via intravenous injection into lethally irradiated NOD.Cg-Rag1 tm1Mom Il2rg tm1Wjl/SzJ immunodeficient mice (the Jackson Laboratory), as previously described.14,15 We treated secondary recipients with vehicle only or with tamoxifen (5 mg/mouse) by intraperitoneal injection to induce deletion of the Hes1 locus.

We infected NOTCH1 (NOTCH1 L1601P ΔPEST)-induced T-ALL cells with lentiviral particles expressing the mCHERRY fluorescent protein and luciferase (Migr-mCHERRY-LUC) and injected them intravenously into C57BL/6 mice. After verification of tumor engraftment (5% green fluorescent protein-positive T-ALL lymphoblasts in peripheral blood), we treated groups of 6 animals with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide) or Perhexiline (53.68 mg⋅kg−1). We evaluated disease progression and therapy response by in vivo bioimaging with the In Vivo Imaging System (Xenogen).

Microarray and RNAseq expression analysis

CUTLL1 cells infected with shLuciferase (shLUC) and shHES1 were collected 72 hours after puromycin selection. RNA was isolated, labeled, and hybridized to the HumanT-12v4 Expression BeadChip (Illumina), using standard procedures. Cells from ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/flox T-ALL were cultured in vitro and treated for 36 hours with ethanol or 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen. RNA was isolated, labeled, and hybridized to the MouseWG-6 v2.0 Expression BeadChip (Illumina), using standard procedures. Raw gene expression data were log2 transformed and quantile-normalized, using MATLAB. Differentially expressed transcripts were analyzed by t-test and fold change. Cross comparison of gene signatures induced by HES1 shRNA knock-down, Hes1 knockout, NOTCH1 inactivation by γ-secretase inhibitor treatment,16 and perhexiline treatment were evaluated using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)17 performed in MATLAB, using the t-test metric and 1000 permutation of the gene lists. Similarly, GSEA was used to test for enrichment of gene sets from the c2 Molecular Signature Database against the ranked list of genes sorted by t-score comparing HES1 shRNA knock-down vs control.

For Connectivity Map analysis18 a gene set consisting of the top 250 regulated genes by fold change (P < .05) on Hes1 knockout in T-ALL lymphoblasts was used as input for using the Broad Institute connectivity map interface (www.broad.mit.edu/cmap).

Gene expression profiling of triplicate CUTLL1 cell cultures treated with perhexiline (10 µM [50% inhibitory concentration]) or vehicle only for 48 hours was performed using RNAseq analysis via Illumina Hiseq sequencing following standard procedures, as detailed in the supplemental Materials and methods.

Microarray and RNAseq data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession numbers GSE65872, GSE66014, and GSE65863).

Quantitative real-time PCR

We performed reverse transcription reactions with the ThermoScript reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) system (Invitrogen) and analyzed the resulting complementary DNA products by quantitative real-time PCR (FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix; Roche), using a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression levels were normalized, using Gapdh as a reference control.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Western blot and immunoprecipitation were performed using standard procedures. The antibody against HES1 was from Aviva Systems Biology Corp (ARP32372_T100). Puma (SC-28226) and GAPDH (SC-20357) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, and the antibody against mouse Gapdh was from Cell Signaling Technology (5174S).

Flow cytometry analysis of hematopoietic populations

To study the effects of perhexiline in the hematopoietic compartment and in T-cell progenitors, 6-week-old C57B6 mice were treated for 5 consecutive days with perhexiline (53.68 mg⋅kg−1). Flow cytometry analyses were performed in a FACSCanto flow cytometer, using FACSDiva (BD Biosciences), as detailed in the supplemental Materials and methods.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analysis by Student t test. Survival in mouse experiments was represented with Kaplan-Meier curves, and significance was estimated with the log-rank test (Prism GraphPad).

Results

HES1 is required for the survival of NOTCH1-driven T-ALL

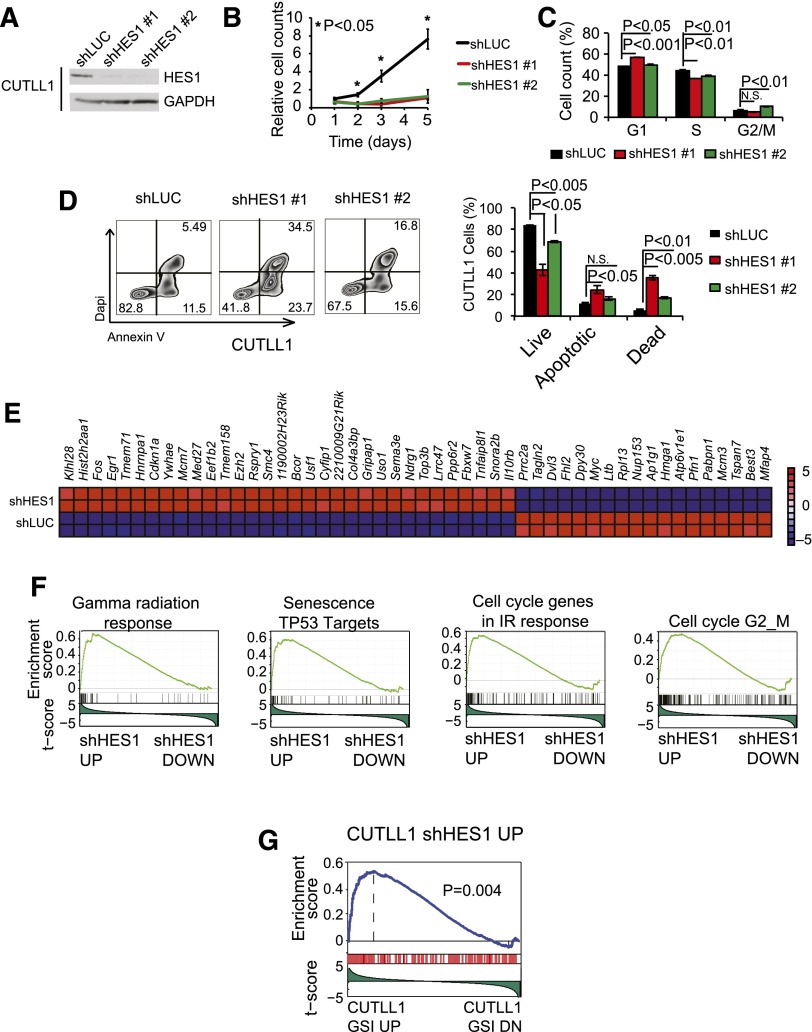

To assess the role of HES1 in the maintenance of human NOTCH1-induced T-ALL, we analyzed the effects of HES1 knockdown in CUTLL1 cells, a NOTCH1-driven human T-ALL cell line expressing a truncated and constitutively active form of NOTCH1, as a result of the t(7;9)(q34;q34) chromosomal translocation16; and in DND41 and MOLT4 cells, 2 well-characterized T-ALL lines harboring activating mutations in NOTCH1.2 In these experiments, and consistent with previous reports,6 lentiviral shRNA knockdown of HES1 (Figure 1A; supplemental Figures 1 and 2, available on the Blood Web site) resulted in a marked decrease in cell growth compared with shLUC controls (Figure 1B; supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle progression showed mild defects in the proliferation of HES1-depleted cells with a modest accumulation of G1 and G2-M cells (Figure 1C). In addition, annexin V staining revealed a marked increase in programmed cell death on HES1 inactivation (Figure 1D; supplemental Figures 1 and 2). These results demonstrate a key role for HES1 in the maintenance of NOTCH1-induced T-ALL and functionally implicate HES1 in leukemia cell survival.

Figure 1.

Cellular and transcriptional effects of HES1 knockdown in human T-ALL cells. (A) Western blot analysis of HES1 expression in CUTLL1 T-ALL cells transduced with shRNAs targeting the Renilla luciferase gene (shLUC) or HES1 (shHES1). (B) Quantification of cell growth in CUTLL1 cells expressing shLUC or shHES1. (C) Cell cycle analysis of CUTLL1 cells expressing shLUC or shHES1. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots after annexin V-allophycocyanin (annexin V-APC) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining and quantification of apoptosis in CUTLL1 cells expressing shLUC or shHES1. Percentage populations are indicated in each quadrant. (E) Heat map representation of the top 50 differentially expressed genes (P < .01) between shLUC and shHES1 CUTLL1 cells. The scale bar shows color-coded differential expression, with red indicating higher levels and blue indicating lower levels of expression. (F) Representative examples of gene set enrichment plots corresponding to GSEA analysis of MSigDB C2 data sets enriched in the expression signature associated with shHES1 CUTLL1 cells compared with shLUC controls. (G) GSEA analysis plot of genes upregulated on HES1 shRNA knockdown in the expression signature associated with GSI-induced NOTCH1 inhibition in CUTLL1 cells. Bar graphs indicate mean values of triplicate measurements, and error bars represent standard deviation.

To assess the mechanisms by which HES1 depletion induces apoptosis of T-ALL cells, we analyzed the transcriptional programs associated with HES1 knockdown. Microarray gene expression profiling of shHES1 CUTLL1 cells and shLUC CUTLL1 controls identified 32 upregulated and 18 downregulated transcripts (fold change, >1.57; P < .01) on HES1 inactivation (Figure 1E). Moreover, genes upregulated on HES1 inactivation were significantly enriched in DNA damage response genes and TP53 targets (Figure 1F). In addition, and in agreement with an established role of HES1 as a transcriptional repressor downstream of NOTCH1, GSEA showed that the genes upregulated on HES1 shRNA inactivation were significantly enriched in the gene expression signature upregulated on γ-secretase inhibitor treatment-induced NOTCH1 inhibition in CUTLL1 cells (Figure 1G). Overall, these results support a major role for HES1 downstream of NOTCH1 in T-ALL as a negative regulator of tumor suppressor pathways and link the transcriptional programs repressed by HES1 with leukemia cell survival.

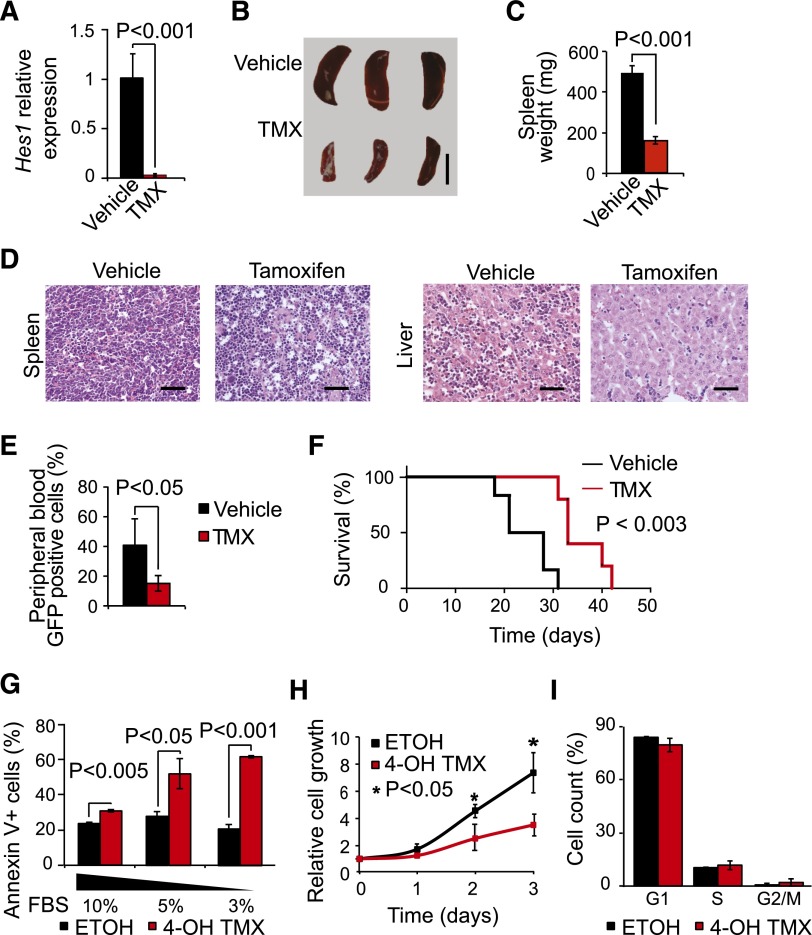

To test the in vivo requirement for Hes1 in the proliferation and survival of primary T-ALL cells, we evaluated the effects of conditional Hes1 gene inactivation on NOTCH1-induced leukemogenesis in mice. To this end, we infected hematopoietic progenitors from tamoxifen-inducible Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1 heterozygous (Hes1flox/wt) and homozygous (Hes1flox/flox) knockout mice12 with retroviruses driving the expression of a mutant oncogenic form of NOTCH1 (ΔE-NOTCH1).19 Consistent with previous reports,15 transplantation of activated NOTCH1-expressing cells resulted in rapid development of NOTCH1-driven leukemias with a characteristic T-cell phenotype (supplemental Figure 3). Next, we transplanted tamoxifen-inducible Hes1 knockout (ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/flox) T-ALL into sublethally irradiated recipients, which, on T-ALL development (40%-70% blasts in peripheral blood), were treated with tamoxifen to induce Cre-mediated deletion of the Hes1 gene or with vehicle only as control. Tamoxifen-induced activation of Cre recombinase rapidly and effectively abrogated Hes1 expression (Figure 2A). Remarkably, genetic ablation of Hes1 in mouse NOTCH1-induced leukemias resulted in marked antileukemic effects in vivo, a result consistent with previous reports on the essential role of Hes1 in mouse NOTCH1-induced leukemias.6 Thus, analysis of leukemia tumor burden 24 hours after Hes1 deletion revealed a marked decrease in spleen size in tamoxifen-treated animals compared with in controls (Figure 2B-C). Moreover, histologic analysis of spleen and liver tissues revealed a profound decrease in leukemia infiltration and starry sky morphology indicative of extensive apoptosis (Figure 2D). These observations were validated with an independent ΔE-NOTCH1 tamoxifen-inducible Hes1 knockout T-ALL (supplemental Figure 4). In contrast, recipient mice bearing heterozygous conditional tamoxifen-inducible Hes1 knockout T-ALL tumors (ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/wt) showed no antileukemic response to tamoxifen (supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Antileukemic effects of Hes1 inactivation in T-ALL. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Hes1 expression across tumor cells isolated from Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL (ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/flox)-bearing mice after 24 hours of treatment with vehicle only (n = 3) or tamoxifen (n = 3) in vivo. (B) Representative image of mouse spleens and (C) quantification of spleen weight of Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia-bearing mice treated with vehicle only or tamoxifen for 24 hours. Scale bar represents 1 cm. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue micrographs of liver and spleen sections from Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia-bearing mice treated with vehicle or tamoxifen. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (E) Quantification of leukemia lymphoblasts as percentage of green fluorescent protein-positive cells in Hes1 conditional knockout NOTCH1-induced leukemia-bearing mice treated with vehicle only (n = 6) or tamoxifen (n = 5) in vivo. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Hes1 conditional knockout NOTCH1-induced leukemia-bearing mice treated with vehicle only (n = 6) or tamoxifen (n = 5) in vivo. (G) Quantification of apoptosis in Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia cells treated with ethanol (ETOH) as control or tamoxifen (4-OH TMX) in vitro. (H) Quantification of cell proliferation in Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia cells treated with vehicle or tamoxifen in vitro. (I) Cell cycle analysis of Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia cells treated with vehicle or tamoxifen in vitro. Bar graphs indicate mean values of triplicate measurements; error bars represent standard deviation.

To analyze the effects of Hes1 inactivation in leukemia progression and survival, we transplanted Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL cells into sublethally irradiated isogenic recipients and treated them with vehicle only (control group) or tamoxifen (Hes1-deleted group). In this experiment, tamoxifen-induced Hes1 deletion significantly decreased circulating leukemia lymphoblasts 2 weeks after transplant (Figure 2E) and markedly prolonged survival (P < .005) (Figure 2F). Moreover, in vitro Hes1 inactivation in mouse NOTCH1-induced leukemia cells increased apoptosis, particularly under low serum culture conditions, with no significant effects on cell cycle progression (Figure 2G-I). These results demonstrate that the impaired cell survival induced by genetic ablation of Hes1 is mediated by cell autonomous mechanisms, confirming a major role for Hes1 in the maintenance of primary NOTCH1-induced T-ALL and supporting a potential role for Hes1 as a therapeutic target in this disease.

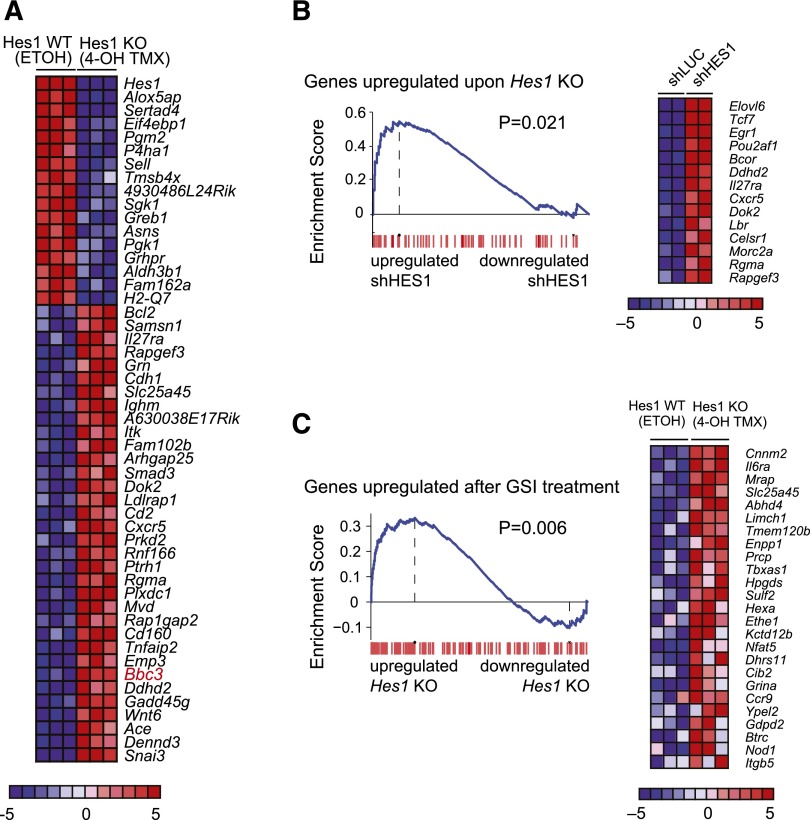

HES1 directly inhibits proapoptotic factor BBC3

Next, we analyzed the transcriptional programs triggered on Hes1 knockout in primary NOTCH1-induced T-ALL lymphoblasts in vitro. Microarray analysis of Hes1 knockout T-ALL cells collected 36 hours after tamoxifen treatment identified 34 upregulated and 17 downregulated genes (fold change, >1.3; P < .005) (Figure 3A). In addition, the genes upregulated on genetic deletion of Hes1 were significantly enriched for genes that make up the transcriptional signature associated with HES1 shRNA-mediated depletion in CUTLL1 T-ALL cells (Figure 3B). Consistent with a major role of Hes1 as a transcriptional repressor downstream of NOTCH1, we also observed a significant positive enrichment for mouse genes upregulated on Hes1 deletion in the upregulated gene expression signature triggered by NOTCH1 inactivation via γ-secretase inhibitor treatment of mouse NOTCH1-induced T-ALL cells (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Convergent gene expression programs in human and mouse NOTCH1-induced T-ALL cells on HES1 inactivation. (A) Heat map representation of the top differentially expressed genes between Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL (ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/flox) cells treated with vehicle only (ETOH) or tamoxifen (4-OH TMX) in vitro. The scale bar shows color-coded differential expression, with red indicating higher levels and blue indicating lower levels of expression. (B) GSEA enrichment plot and top leading-edge genes upregulated after Hes1 knockout compared with the transcriptional signature associated with HES1 knockdown in CUTLL1 cells. (C) GSEA enrichment plot and top leading-edge genes upregulated after GSI treatment of NOTCH1-induced murine T-ALL cells compared with the transcriptional signature induced by tamoxifen treatment in Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia cells (Hes1 KO).

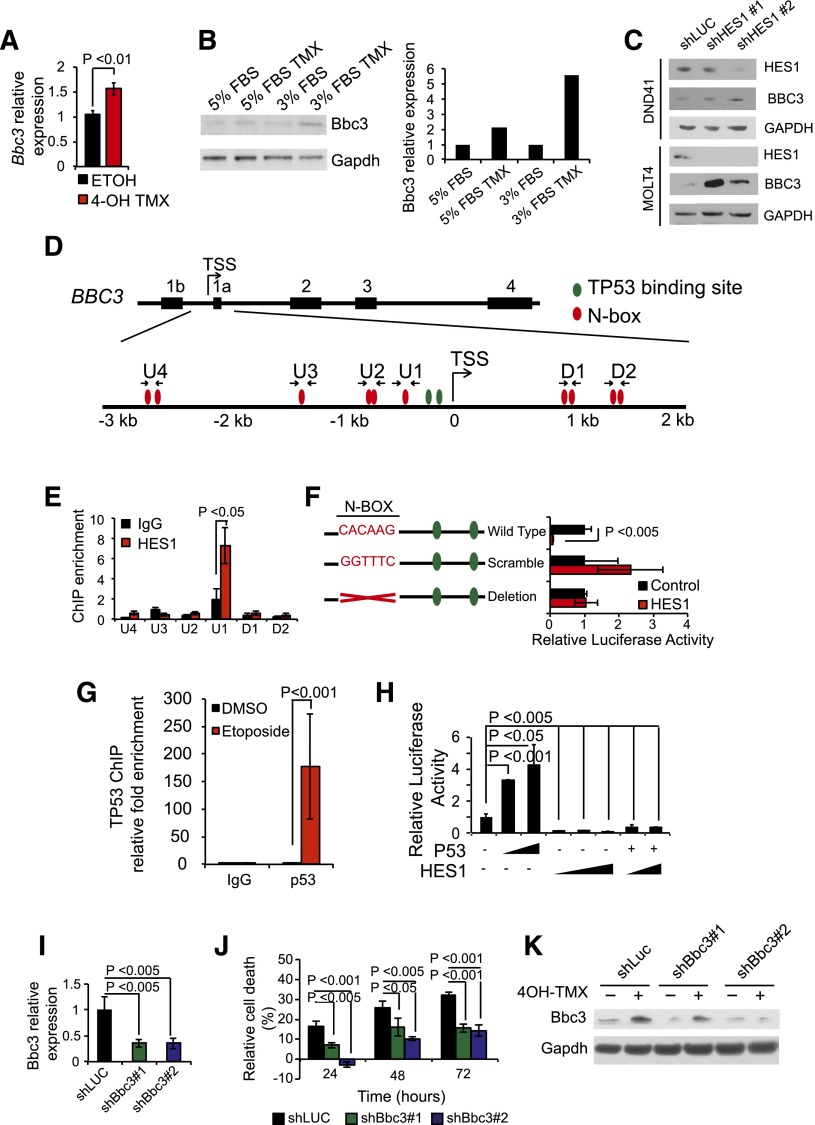

Most notably, the transcriptional program upregulated by Hes1 inactivation included important mediators of cell signaling such as Wnt6, Cxcr5, Smad3, and Il27ra, as well as Bbc3, the gene encoding Puma, a major BH3-only proapoptotic factor (Figure 3A). On the basis of these results, and given the well-established role of Puma as mediator of programmed cell death downstream of multiple apoptotic stimuli, including TP53 activation,20 we hypothesized that HES1 could promote leukemia cell survival via direct transcriptional repression of the Bbc3 gene. RT-PCR and western blot analysis of Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL cells treated with tamoxifen verified transcriptional upregulation of Bbc3 expression (Figure 4A) and Puma protein upregulation (Figure 4B) on Hes1 inactivation. Consistently, shRNA knockdown of HES1 induced an increase of BBC3 expression in DND41 and MOLT4 T-ALLs (Figure 4C). Analysis of the proximal regulatory sequences (+2 kb to −3 kb) flanking the BBC3 transcription initiation site identified 10 N-box motif elements that could potentially mediate transcriptional repression via direct HES1 binding in human T-ALL (Figure 4D). Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis using a HES1 antibody demonstrated specific HES1 binding to the −415 to −410 BBC3 proximal promoter, a region containing a single canonical N-box site (U1) (Figure 4E-F). This putative regulatory element located −410 bp from the BBC3 transcription initiation site is equivalent to a Hes1 binding motif in the mouse genome located −393 to −388 from the Bbc3 transcription initiation site and is in close proximity to 2 well-characterized TP53 binding sites (Figure 4D) actively occupied by TP53 on activation of DNA damage response in T-ALL cells (Figure 4G) and known to mediate BBC3 upregulation downstream of TP53 activation.21 These findings suggest a role for HES1 in antagonizing TP53-mediated BBC3 transcriptional upregulation in T-ALL. To test this possibility, we analyzed the effect of HES1 expression on the activity of a −544 to −121 BBC3 promoter construct in luciferase reporter assays. In these experiments, HES1 expression induced a 91% (∼11-fold) downregulation of the BBC3 reporter activity, which was suppressed on mutation or deletion of the −410 BBC3 N-box sequence occupied by HES1 (Figure 4F). Given that TP53 acts as major driver of BBC3 expression,22 we then analyzed the effects of HES1 on TP53-BBC3 regulation. Consistent with previous reports,22 BBC3 reporter activity was induced on transfection of TP53-expressing constructs (Figure 4H). Moreover, coexpression of HES1 effectively abrogated TP53-induced BBC3 upregulation (Figure 4H). Overall, these results identify BBC3 as a direct HES1 target gene and support a potentially dominant role for HES1-mediated repression in BBC3 transcriptional regulation.

Figure 4.

Direct Hes1 downregulation of Bbc3 expression inhibits apoptosis in T-ALL cells. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR of Bbc3 expression in Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL (ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/flox) after treatment with vehicle only (ETOH) or tamoxifen (4-OH TMX) in vitro. (B) Western blot analysis of Bbc3 expression in Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia cells and on tamoxifen-induced Hes1 deletion. Bar graph indicates the corresponding quantification of protein expression. (C) Western blot analysis of BBC3 expression DND41 and MOLT4 cells on HES1 shRNA knockdown. (D) Schematic representation of the BBC3 locus indicating the potential HES1 N-box and TP53 binding sites. (E) Relative enrichment of the BBC3 promoter sequences in control (immunoglobulin G) and HES1 ChIPs from CUTLL1 T-ALL cells. (F) Luciferase reporter activity in HEK 293T cells of a BBC3 promoter construct (Wild Type), a BBC3 promoter containing a scramble sequence in the N-box bound by HES1 (Scramble), and a BBC3 promoter with the deletion of the N-box bound by HES1 (Deletion). (G) Relative enrichment of the BBC3 promoter sequences in control (immunoglobulin G) and TP53 ChIPs from TP53 competent MOLT4 T-ALL cells in basal conditions and on etoposide-induced DNA damage. (H) Luciferase reporter activity of the BBC3 wild-type reporter construct in response to increasing doses of TP53, increasing doses of HES1, and the combination of TP53 and HES1. (I) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Bbc3 expression in Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL (ΔE-NOTCH1 Rosa26 Cre-ERT2 Hes1flox/flox) cells infected with lentiviruses expressing a control shRNA (shLUC) and 2 independent shRNAs targeting Bbc3 (shBbc3 1 and shBbc3 2). (J) Quantization of cell death induced by Hes1 deletion in control (shLUC) and Bbc3 knockdown (shBbc3) in Hes1 conditional knockout T-ALL cells treated with 4-OH tamoxifen. (K) Western blot analysis of Bbc3 knockdown in Hes1 conditional knockout leukemia cells grown in low-serum conditions (3% fetal bovine serum) and on tamoxifen-induced Hes1 deletion. Bar graphs indicate mean values of triplicate measurements; error bars represent standard deviation.

To explore the significance of the Hes1-Bbc3 transcriptional regulatory axis in leukemia cell survival, we then analyzed the effects of Bbc3 depletion on Hes1-knockout-induced apoptosis. Consistent with our previous results, tamoxifen-induced Cre-mediated deletion of Hes1 induced apoptosis in T-ALL lymphoblasts expressing a control shRNA (shLUC) (Figure 4I-J). Notably, however, the apoptotic response triggered by Hes1 deletion was significantly abrogated in T-ALL lymphoblasts on lentiviral expression of 2 independent Bbc3 shRNAs (Figure 4I-K). Taken together, these results identify HES1-mediated downregulation of BBC3 expression as a critical mechanism promoting increased survival in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL.

Identification of perhexiline as a HES1 modulator drug

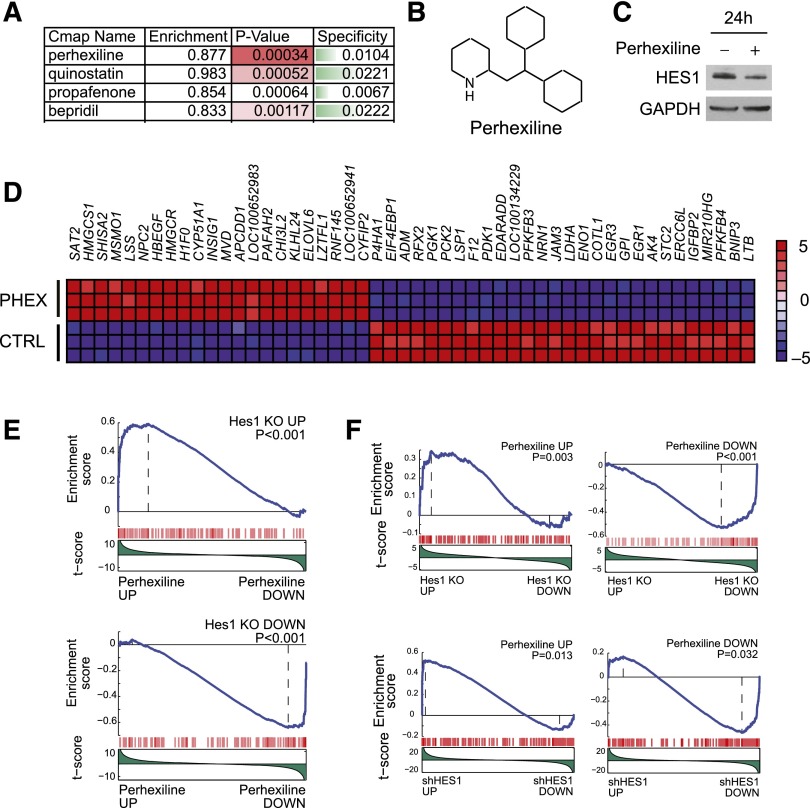

The central role of HES1 in NOTCH1-induced leukemia suggests that abrogation of HES1 activity in leukemia lymphoblasts could be exploited therapeutically. However, despite recent advances in targeting transcription factor complexes with small molecules and synthetic peptides, a direct HES1 inhibitor is not readily available. To overcome this obstacle, we interrogated the Connectivity Map, a large collection of genome-wide transcriptional expression data derived from tumor cells treated with bioactive small molecules,18 for compounds with gene expression signatures overlapping with that induced by Hes1 deletion in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL (Figure 5A). This analysis identified perhexiline, an inhibitor of mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 in clinical use for treatment of cardiac ischemia,23 as a potential therapeutic agent for T-ALL on the basis of its ability to elicit a gene expression signature resembling that induced by Hes1 inhibition (Figure 5A-B). Interestingly, and even though these results do not necessarily imply a direct effect of perhexiline in HES1 expression, we observed HES1 downregulation in CUTLL1 cells treated with this drug (Figure 5C). Gene expression profiling of CUTLL1 T-ALL cells treated with perhexiline revealed a gene expression signature with 120 genes upregulated (fold change, >1.5; P < .001) and 80 genes downregulated (fold change, >1.5; P < .001) (Figure 5D). Notably, and consistent with the reported metabolic modulatory effects of perhexiline in cardiac metabolism, top transcripts downregulated on perhexiline treatment included major glycolytic enzyme genes such as PFKFB4, ENO1, LDHA, and PDK1 (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Identification of perhexiline as a Hes1-signature modulator drug. (A) Top Connectivity Map analysis hits for drugs with signatures overlapping with those induced by Hes1 knockout in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL. (B) Structure of perhexiline. (C) Western blot analysis of HES1 expression in CUTLL1 cells treated with perhexiline. (D) Heat map representation of the top 50 differentially expressed genes (P < .0001) between vehicle-treated and perhexiline-treated CUTLL1 cells. The scale bar shows color-coded differential expression, with red indicating higher levels and blue indicating lower levels of expression. (E) GSEA analysis plots of genes upregulated and downregulated on Hes1 knockout in mouse NOTCH1-induced T-ALL cells in the expression signature induced by perhexiline treatment. (F) GSEA analysis plots of genes upregulated and downregulated on perhexiline treatment in CUTLL1 cells in the expression signature induced by Hes1 knockout in mouse NOTCH1-induced T-ALL cells and in the expression signature induced by HES1 shRNA knockdown in CUTLL1 cells.

Moreover, GSEA analysis of differentially upregulated (n = 132; P < .005) and downregulated (n = 129; P < .005) genes on Hes1 knockout in mouse NOTCH1-induced T-ALL cells revealed a highly significant enrichment in the perhexiline-induced gene expression signature (Figure 5E). In addition, GSEA of differentially upregulated (n = 147; P < .0001) and downregulated (n = 129; P < .0001) genes on perhexiline treatment were significantly enriched in the gene expression signature elicited by Hes1 knockout in mouse leukemia cells and by HES1 knockdown in CUTLL1 cells (Figure 5F). These results support a convergent effect of perhexiline treatment and Hes1 inactivation in T-ALL.

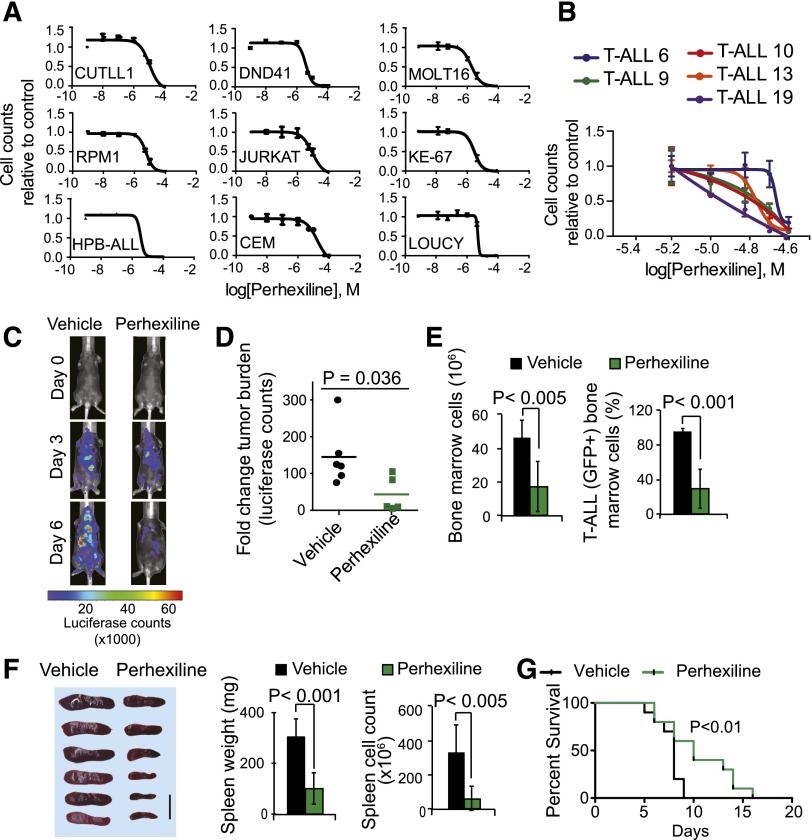

Following these findings, we analyzed the effects of perhexiline treatment on a broad panel of T-ALL cell lines (HPB-ALL, DND41, JURKAT, CCRF-CEM, RPMI-8402, and CUTLL1) harboring activating mutations in NOTCH1.2,16 Treatment with perhexiline induced strong antileukemic responses across all 6 T-ALL lines, with an average 50% inhibitory concentration of 8.43 μM (range, 3.48-17.8 μM) at 72 hours (Figure 6A). Extended analysis of T-ALL cell lines lacking NOTCH1 activation (MOLT16, LOUCY, and KE37) showed that perhexiline is also active against these NOTCH1-negative tumors (Figure 6A). This finding supports that the targets of perhexiline may also be relevant in the context of T-ALL cells transformed by NOTCH1-independent mechanisms. In addition, and most important, perhexiline treatment of primary human T-ALL samples demonstrated significant antileukemic effects for this drug in all 5 leukemias tested (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Antileukemic effects of perhexiline in T-ALL. (A) Dose-response cell viability curves (relative cell number equivalents compared with vehicle-treated controls) of T-ALL cell lines treated with perhexiline in triplicate. (B) Dose-response cell viability curves (relative cell number equivalents compared with vehicle-treated controls) of primary T-ALL patient samples treated with perhexiline in triplicate. (C,D) Representative images (C) and quantitative changes in tumor burden (D) assessed by luciferase in vivo bioimaging in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL-bearing mice treated with vehicle only or perhexiline. (E) Quantitative analysis of cellularity and leukemia infiltration (assessed by green fluorescent protein expression) in bone marrow from NOTCH1-induced T-ALL bearing mice (n = 6) treated with vehicle only or perhexiline. (F) Mouse spleens from NOTCH1-induced T-ALL bearing mice treated with vehicle only or perhexiline. Spleen weight and cellularity in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL-bearing mice treated with vehicle only or perhexiline. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice harboring NOTCH1-induced T-ALL treated for 5 consecutive days with vehicle only (n = 10) or perhexiline (n = 10). Graphs indicate mean values; error bars represent standard deviation.

Finally, we evaluated the efficacy of perhexiline treatment in mice transplanted with primary NOTCH1-induced mouse T-ALL cells. In this experiment, in vivo bioimaging revealed significant antitumor responses in perhexiline-treated animals after 5 days of treatment (Figure 6C-G). Indeed, examination of bone marrow and spleen revealed a marked reduction in spleen size and leukemia infiltration in the perhexiline-treated group compared with controls (Figure 6E-F). Consistently, NOTCH1-induced T-ALL bearing mice treated with perhexiline showed significantly extended survival compared with vehicle-treated controls (P < .05) (Figure 6G). Notably, analysis of hematopoietic progenitors and stem cells in C57BL/6 mice treated with perhexiline revealed no detrimental effects in the hematopoietic system other than a mild reduction in the number of DN4 and DP thymocytes (supplemental Figure 6).

Discussion

Malignant transformation in T-ALL is driven by genetic alterations that target key aspects of early progenitor T-cell proliferation, metabolism, differentiation, and survival. In this context, oncogenic NOTCH1 acts as a master and pleiotropic oncogenic factor with multiple effector mechanisms. Among NOTCH1 targets, HES1 plays an important role downstream of oncogenic NOTCH1 as regulator of key oncogenic pathways including PI3K and NFKB signaling.7,8,24 The studies outlined here represent the first comprehensive analysis of the phenotypic and transcriptional effects of HES1 loss in NOTCH1-induced T-ALL. Together with previous studies implicating Hes1 in thymocyte development and NOTCH1-induced transformation,6,25 our integrative analysis of human and mouse NOTCH1-driven T-ALLs define a strict requirement for HES1 in tumor maintenance. Multiple direct and indirect downstream effectors of the NOTCH1-HES1 transcriptional regulatory circuitry probably contribute to the loss of cell viability on HES1 inactivation. Our results, shown here, highlight the role of Bbc3, a critical mediator of apoptosis in the apoptotic response induced by loss of Hes1 in T-ALL. Bbc3 induces TP53-dependent apoptosis on DNA damage response and is also involved in TP53-independent cell death induced by serum starvation and cytokine deprivation.21,26,27 The antagonistic interplay between HES1 and TP53 in the induction of BBC3 was documented in our reporter assays and was also reflected in the response of different T-ALL cell lines to HES1 knockdown, with strong induction of BBC3 in the TP53-competent MOLT4 cells and more modest BBC3 accumulation in the TP53-deficient DND41 cell line. Of note, and consistent with the monoallelic expression of mutant dominant negative TP53 in this line,16 we did not detect significant accumulation of BBC3 in CUTLL1 cells (data not shown).

In contrast with the high prevalence of TP53 mutations in most human cancers,28 direct genetic inactivation of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene is rarely found in T-ALL.29 However, the relevance of the TP53 pathway in the pathogenesis of T-ALL is highlighted by the high prevalence of chromosomal deletions encompassing the CDKN2A locus present in more than 70% of T-ALLs.30 Loss of CDKN2A genes P16/INK4A and P19/ARF promotes T-cell transformation by promoting deregulated cell cycle progression31,32 and increased MDM2-mediated TP53 degradation,33,34 respectively. In this setting, we propose that HES1 activation may further impair oncogenic stress-induced apoptosis during T-cell transformation by blunting the induction of BBC3 expression. Moreover, HES1-mediated downregulation of BBC3 may also facilitate the survival of T-ALL lymphoblasts in cytokine-poor microenvironments as they infiltrate peripheral tissues during disease progression.

The development of intensified combination chemotherapies for T-ALL has resulted in markedly improved survival rates in both children and adults with this disease.35 However, patients with primary resistant T-ALL, or those whose leukemia relapses after a transient response, have few effective therapeutic options and face a dismal prognosis,36,37 highlighting the need to develop more effective treatment options. Our identification of HES1 as a major mediator of T-ALL cell survival and perhexiline as a HES1-signature antagonist drug with remarkable single-agent antileukemic activity in vitro and in vivo may have a direct clinical effect, as perhexiline is already in clinical use for the treatment of cardiac ischemia and refractory angina in humans.38,39 Mechanistically, the anti-ischemic effects of perhexiline have been linked with inhibition of the CPT-1 and CPT-2 palmitoyltransferases, which results in impaired fatty acid metabolism and decrease of oxygen demand in the myocardium.23 Notably, NOTCH1 signaling has been linked with increased glucose metabolism during thymocyte development,40 and regulation of anabolic pathways may play an important role in the response of T-ALL cells to anti-NOTCH1 therapies.11 In this context, the convergent antileukemic effects and transcriptional programs of perhexiline and HES1 inhibition in T-ALL could suggest a previously unrecognized role of perhexiline in the regulation of HES1 transcriptional complexes. However, it is also possible that the antileukemic effects of perhexiline do not involve direct HES1 inhibition but, instead, may modulate other downstream effector pathways common to those triggered by HES1 inactivation.

Overall, our results highlight a central role for HES1 and BBC3 in the control of NOTCH1-induced leukemia cell survival and identify perhexiline as a highly active antileukemic drug for the treatment of T-ALL.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Ludwig (Ohio State University) for the ROSACre-ERT2/+ mouse, R. Kopan (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati) for the E-NOTCH1 construct, W. Gu (Columbia University Medical Center) for the TP53 expression construct, and R. Baer and A. Wendorff for helpful revisions of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01CA120196), the Stand Up to Cancer Innovative Research Award (A.A.F), the Chemotherapy Foundation (A.A.F.), and the Swim Across America Foundation (A.A.F).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A.S. designed the study, performed most of the experiments, and wrote the manuscript; A.A.-I. and Y.Q. performed bioinformatics analyses; L.X. assisted in animal experiments; M.S-M performed experiments; L.B. analyzed hematopoietic progenitor populations; R.K. provided the Hes1f/f mice; and A.A.F designed the study, supervised research, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Adolfo Ferrando, Institute for Cancer Genetics, Columbia University Medical Center, 1130 St Nicholas Ave, ICRC-402A, New York, NY 10032; e-mail: af2196@columbia.edu.

References

- 1.Van Vlierberghe P, Ferrando A. The molecular basis of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3398–3406. doi: 10.1172/JCI61269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306(5694):269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paganin M, Ferrando A. Molecular pathogenesis and targeted therapies for NOTCH1-induced T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Rev. 2011;25(2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarriault S, Le Bail O, Hirsinger E, et al. Delta-1 activation of notch-1 signaling results in HES-1 transactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(12):7423–7431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomita K, Hattori M, Nakamura E, Nakanishi S, Minato N, Kageyama R. The bHLH gene Hes1 is essential for expansion of early T cell precursors. Genes Dev. 1999;13(9):1203–1210. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wendorff AA, Koch U, Wunderlich FT, et al. Hes1 is a critical but context-dependent mediator of canonical Notch signaling in lymphocyte development and transformation. Immunity. 2010;33(5):671–684. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palomero T, Dominguez M, Ferrando AA. The role of the PTEN/AKT Pathway in NOTCH1-induced leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(8):965–970. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.8.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinosa L, Cathelin S, D’Altri T, et al. The Notch/Hes1 pathway sustains NF-κB activation through CYLD repression in T cell leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palomero T, Lim WK, Odom DT, et al. NOTCH1 directly regulates c-MYC and activates a feed-forward-loop transcriptional network promoting leukemic cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(48):18261–18266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606108103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong F, Brunet de la Grange P, Gerby B, et al. NOTCH is a key regulator of human T-cell acute leukemia initiating cell activity. Blood. 2009;113(8):1730–1740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13(10):1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imayoshi I, Shimogori T, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R. Hes genes and neurogenin regulate non-neural versus neural fate specification in the dorsal telencephalic midline. Development. 2008;135(15):2531–2541. doi: 10.1242/dev.021535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo K, McMinn JE, Ludwig T, et al. Disruption of peripheral leptin signaling in mice results in hyperleptinemia without associated metabolic abnormalities. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):3987–3997. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang MY, Xu L, Shestova O, et al. Leukemia-associated NOTCH1 alleles are weak tumor initiators but accelerate K-ras-initiated leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(9):3181–3194. doi: 10.1172/JCI35090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pear WS, Aster JC, Scott ML, et al. Exclusive development of T cell neoplasms in mice transplanted with bone marrow expressing activated Notch alleles. J Exp Med. 1996;183(5):2283–2291. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palomero T, Barnes KC, Real PJ, et al. CUTLL1, a novel human T-cell lymphoma cell line with t(7;9) rearrangement, aberrant NOTCH1 activation and high sensitivity to gamma-secretase inhibitors. Leukemia. 2006;20(7):1279–1287. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, et al. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science. 2006;313(5795):1929–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopan R, Schroeter EH, Weintraub H, Nye JS. Signal transduction by activated mNotch: importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(4):1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hikisz P, Kiliańska ZM. PUMA, a critical mediator of cell death—one decade on from its discovery. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2012;17(4):646–669. doi: 10.2478/s11658-012-0032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han J, Flemington C, Houghton AB, et al. Expression of bbc3, a pro-apoptotic BH3-only gene, is regulated by diverse cell death and survival signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(20):11318–11323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201208798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7(3):683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy JA, Unger SA, Horowitz JD. Inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 in rat heart and liver by perhexiline and amiodarone. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52(2):273–280. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong GW, Knowles GC, Mak TW, Ferrando AA, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. HES1 opposes a PTEN-dependent check on survival, differentiation, and proliferation of TCRβ-selected mouse thymocytes. Blood. 2012;120(7):1439–1448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomita K, Ishibashi M, Nakahara K, et al. Mammalian hairy and Enhancer of split homolog 1 regulates differentiation of retinal neurons and is essential for eye morphogenesis. Neuron. 1996;16(4):723–734. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffers JR, Parganas E, Lee Y, et al. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(4):321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu WS, Heinrichs S, Xu D, et al. Slug antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors by repressing puma. Cell. 2005;123(4):641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(1):a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamura M, Ohnishi H, Guo SX, et al. Alterations of the p53, p21, p16, p15 and RAS genes in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 1999;23(2):115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hebert J, Cayuela JM, Berkeley J, Sigaux F. Candidate tumor-suppressor genes MTS1 (p16INK4A) and MTS2 (p15INK4B) display frequent homozygous deletions in primary cells from T- but not from B-cell lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Blood. 1994;84(12):4038–4044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho RA. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell. 1996;85(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature. 1993;366(6456):704–707. doi: 10.1038/366704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamijo T, Weber JD, Zambetti G, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Functional and physical interactions of the ARF tumor suppressor with p53 and Mdm2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(14):8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel MF, et al. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell. 1997;91(5):649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldberg JM, Silverman LB, Levy DE, et al. Childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute acute lymphoblastic leukemia consortium experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3616–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oudot C, Auclerc MF, Levy V, et al. Prognostic factors for leukemic induction failure in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and outcome after salvage therapy: the FRALLE 93 study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(9):1496–1503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Killalea SM, Krum H. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of perhexiline in the treatment of ischemic heart disease. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2001;1(3):193–204. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200101030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee L, Horowitz J, Frenneaux M. Metabolic manipulation in ischaemic heart disease, a novel approach to treatment. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(8):634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciofani M, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. A survival guide to early T cell development. Immunol Res. 2006;34(2):117–132. doi: 10.1385/IR:34:2:117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]