Abstract

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is generally attributed to the progressive vascular accumulation of lipoproteins and circulating monocytes in the vessel walls leading to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. This is known to be regulated by the local vascular geometry, haemodynamics and biophysical conditions. Here, an isogeometric analysis framework is proposed to analyse the blood flow and vascular deposition of circulating nanoparticles (NPs) into the superficial femoral artery (SFA) of a PAD patient. The local geometry of the blood vessel and the haemodynamic conditions are derived from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed at baseline and at 24 months post intervention. A dramatic improvement in blood flow dynamics is observed post intervention. A 500% increase in peak flow rate is measured in vivo as a consequence of luminal enlargement. Furthermore, blood flow simulations reveal a 32% drop in the mean oscillatory shear index, indicating reduced disturbed flow post intervention. The same patient information (vascular geometry and blood flow) is used to predict in silico in a simulation of the vascular deposition of systemically injected nanomedicines. NPs, targeted to inflammatory vascular molecules including VCAM-1, E-selectin and ICAM-1, are predicted to preferentially accumulate near the stenosis in the baseline configuration, with VCAM-1 providing the highest accumulation (approx. 1.33 and 1.50 times higher concentration than that of ICAM-1 and E-selectin, respectively). Such selective deposition of NPs within the stenosis could be effectively used for the detection and treatment of plaques forming in the SFA. The presented MRI-based computational protocol can be used to analyse data from clinical trials to explore possible correlations between haemodynamics and disease progression in PAD patients, and potentially predict disease occurrence as well as the outcome of an intervention.

Keywords: finite-element modelling, atherosclerosis, magnetic resonance imaging, nanoparticles, vascular adhesion

1. Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is often referred to as a vascular disease inducing the progressive formation of plaques (atherogenesis), specifically in the arteries that carry blood to the limbs, head, kidneys and stomach. PAD has been associated with an increased risk of atherothrombotic cardiovascular events and mortality and, as such, it is considered an early marker of coronary artery disease, strokes and myocardial infarction [1–4]. PAD management can be categorized into pharmacological (lipid-lowering treatments), surgical (deployment of stents, revascularization and vascular surgery) and a combination of the two [1,5]. Following the well-accepted oxidative modification hypothesis, the first step in atherogenesis is the accumulation of circulating low-density lipoprotein particles into the sub-intimal space of the arterial wall [6]. This accumulation is generally higher at sites of disturbed flow: low flow, separation, flow reversal and even turbulence [7–12]. At these sites, typically, larger rates of endothelial cell (EC) proliferation and apoptosis, higher vascular permeability, overexpression of EC adhesion molecules (ICAM1, VCAM1 and E-selectin) and the release of chemo-attractants from ECs are consistently observed [13,14]. This clearly emphasizes the importance of an accurate determination of the local flow field to potentially predict the occurrence of the disease and the outcome of any intervention. The main objective of this work is to bring together a number of available technologies to build a patient-specific analysis framework that can be used to analyse data from clinical trials to provide insights into PAD management. To that end, this paper aims to serve as a proof of concept and presents some relevant results to demonstrate the feasibility of our approach.

Finite-element-based isogeometric analysis is one of the prominent approaches [15] that can be efficiently used to simulate cardiovascular biomechanics problems in patient-specific three-dimensional vascular models [16–20] (for a more comprehensive review, readers are referred to the following, to cite but a few: [9,10,21–23]). The isogeometric framework uses geometric primitives (NURBS: non-uniform rational B-splines) developed in computer-aided design and computational geometry, which allows us to represent geometrical objects with a higher degree of precision and smoothness (higher order basis functions with continuous derivatives) than piecewise polynomials (continuous, but not smooth, basis functions) commonly used in finite-element analysis [24]. The ability of NURBS to accurately represent smooth exact geometries (i.e. arterial systems), which is not attainable in the faceted finite-element representation, renders fluid and structural computations more physiologically realistic. Also, the parametric definition of NURBS meshes allows automatic refinement of the boundary layer region near the arterial wall, which is crucial for the overall numerical stability and for the accurate computation of wall quantities, such as the wall shear rates and stresses, wall permeability and adhesion [16]. Following this approach, the authors have solved several structural, fluid and solid mechanics problems within the biomedical field and others [25–27]. The methodology has been shown to be suitable for cardiovascular applications because of its precise and efficient geometric modelling, capability to appropriately capture both laminar and turbulent flow regimes, and accurate representation of stresses [28].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides excellent soft-tissue contrast without ionizing radiation and it has been extensively used to image atherosclerotic plaques and plaque composition [29]. However, the study of atherosclerosis in lower extremity vessels, including the superficial femoral artery (SFA), presents various MRI challenges, due to potential involuntary muscle twitching causing motion artefacts, vessel calibre and tortuosity [30]. Although recent advances in coil technology allow full coverage of the SFA, sampling a large enough field of view (FOV) remains challenging in the domain of high-resolution plaque imaging. New three-dimensional MRI sequences such as three-dimensional motion-sensitized driven equilibrium prepared rapid gradient echo (3D-MERGE) have shown promising results for imaging of the peripheral vessels. Multi-contrast MRI, two-dimensional phase contrast (PC), four-dimensional flow MRI and magnetic resonance (MR) angiography have been described extensively [31–33]. These sequences can be used to obtain patient-specific information including the vascular geometry, inflow/outflow velocity profiles and the velocity field within the vascular tree of interest over time. These data can be readily used to prescribe the physical domain (geometry), the initial and boundary conditions in any patient-specific computational framework.

In this work, the geometry and haemodynamic conditions for an SFA of a PAD patient are extracted from MRI at baseline and 24 months after stent implantation. Then isogeometric analysis is used to analyse the blood flow dynamics within the SFA over a full cardiac cycle. Near-wall quantities such as time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS), the oscillatory shear index (OSI) and relative residence time (RRT) are also investigated. Finally, the vascular transport of systemically injected nanoparticles (NPs), targeted to different inflammatory vascular molecules such as VCAM-1, E-selectin and ICAM-1 that are known to overexpress at the diseased site, is analysed. In particular, the surface density of these NPs within the SFA is estimated as a function of time and vascular molecules (receptors) to explore the use of nanomedicine in the non-invasive imaging and treatment of PAD patients. The possible relationship between local haemodynamics and the particle distribution pattern is also studied.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Imaging data acquisition and magnetic resonance imaging

The MRI data used in this analysis were obtained from the Effect of Lipid Modification on Peripheral Artery Disease after Endovascular Intervention Trial (ELIMIT) [30]. ELIMIT was a double-blind and double-placebo-controlled trial in PAD patients with the goal of studying the efficacy of intensive lipid-modifying triple therapy (simvastatin, ezetimibe and extended-release niacin) versus standard lipid-modifying mono-therapy (simvastatin) on the progression of atherosclerosis in the SFA as quantified by high-resolution MRI. The main findings of ELIMIT have been reported previously [30]. Briefly, patients underwent MRI of the distal SFA at baseline, six months, 12 months and 24 months with a 3.0 T system (Signa Excite; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using a unilateral phased array coil with a FOV of 8 cm (along the z-axis) and 12 cm (in-plane x- and y-axes; Pathway Biomedical, Inc.). Lipid data were also recorded. The geometries for the current analysis were extracted from proton-density-weighted (PDW) fast spin-echo scans. Sequence parameters of the PDW scans were described previously [30]. ELIMIT participants were also imaged using gated two-dimensional PC sequences, acquired at select locations within the corresponding PDW volumes—typically proximally and distally to SFA lesions. Gated two-dimensional PC sequences were acquired during the same examination with slice thickness = 4 mm, repetition time (TR) = 10.6 ms, echo time (TE) = 4.97 ms, echo train length = 1, bandwidth = 244 Hz pixel−1, 20 frames per cardiac cycle and PC-encoding velocity (VENC) of 120 cm s−1. Serial MRI scans were carefully co-registered across follow-up visits using anatomical landmarks (artery, vein and muscle) [30]. Velocity profiles over the cardiac cycle were obtained at each location using the luminal cross-sectional areas (region of interest (ROI)), the mean signal intensity of the ROIs and the VENC factor.

2.2. Reconstructing the patient-specific vascular geometry

Here, an image-based pipeline, as detailed in [24], is adopted to construct hexahedral solid NURBS meshes for patient-specific vascular geometric models to be used in isogeometric analysis. Briefly, the image quality is first improved by passing the raw imaging data through a preprocessing pipeline for enhancing the contrast, filtering noise, classifying and segmenting regions of various materials. In this work, the segmentation of the lumen and the vessel wall is performed manually with Amira. The target surfaces (the lumen–wall interface) are then extracted by isocontouring the pre-segmented imaging data, followed by the extraction of the vascular skeleton (vessel centrelines) using open-source software [34,35]. Finally, an optimized skeleton-based sweeping method is used to construct hexahedral control meshes employing an in-house numerical code [24] as follows.

The geometry is first decomposed into mapped meshable piecewise linear patches. Each patch is then meshed using a heuristic sweeping method by iteratively running three steps: (i) clustering projected control points to obtain an optimized centreline; (ii) computing the normal of the cross section at each control point on the skeleton (centre points); and (iii) projecting boundary points onto the target surface preserving perpendicularity of cross sections and centreline normal. The first step improves the distribution of centre points on the skeleton, and the second and third steps guarantee good shape of hexahedral elements. The iterative procedure serves as a compromise of these two constraints. Such heuristics could be formulized as an alternating optimization problem [36] whose convergence has been thoroughly studied and thus quality meshes are obtained. Finally, hexahedral solid NURBS are constructed from the control mesh and used in isogeometric analysis to simulate blood flow and particle delivery in the SFA. Figure 1 shows the right SFA geometry generated from MR images of a patient with PAD.

Figure 1.

Patient-specific geometry from MR images. The vascular geometry of a PAD patient is reconstructed using three-dimensional NURBS from the MR images. (a) The stacked segmented slices. (b) The reconstructed SFA, before clinical intervention, and three cross sections taken along the length of the artery depicting the lumen and the vessel wall. (Online version in colour.)

2.3. Governing equations for the fluid flow and particle transport

A continuum-based approach was adopted to simulate blood flow and particle transport within the patient-specific SFA. The details of the mathematical equations and the numerical methodology are reported elsewhere [16,19,25,37]. Briefly, considering blood as an incompressible Newtonian fluid with a dynamic viscosity (μ) of 0.003 Pa-s and a density (ρ) of 1060 kg m−3, blood flow was assumed to be governed by the unsteady Navier–Stokes equations for incompressible flow subjected to appropriate boundary conditions (figure 2). An inflow velocity profile was specified at the inlet, a no-slip boundary condition was prescribed at the rigid and impermeable wall, and a traction-free outflow boundary condition was set at the branch outlet. In order to analyse the flow-field characteristics and its near-wall behaviour, two wall shear-based quantities were calculated over a cardiac cycle with a time period T: (i) the TAWSS

| 2.1 |

|

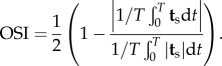

2.2 |

The surface traction vector ts, defined as the tangential component of the traction vector, is calculated from ts = t − (t · n)n, where the traction vector t is computed from the stress tensor σ using the relation t = σn. Here, the OSI characterizes the changes in flow direction and the velocity gradient during a cardiac cycle and can range from 0 (unidirectional flow) to 0.5 (oscillatory flow). RRT is associated with the particle residence time near the wall and combines the information provided by the TAWSS and OSI as follows:

| 2.3 |

Figure 2.

MRI-based computational model—the problem set-up. The geometry of the SFA and the inflow conditions are extracted from the patient-specific MRI data. The adhesion of spherical NPs to the vessel walls of the SFA is mediated by ligand–receptor interactions. The main governing equations and boundary conditions for the problem are included. (Online version in colour.)

High RRT leads to increased uptake of blood-borne particles, which has implications for atherosclerosis [40].

Treating the NPs as passive scalars, the mass transport of the particles is assumed to be governed by an unsteady scalar advection–diffusion equation. This assumption is deemed reasonable for sufficiently small particles travelling in large vessels [41,42]. A bolus of NPs is located at the inlet of the artery segment for the entire duration of simulation (figure 2). This translates to a Dirichlet boundary condition with a volumetric concentration C0 prescribed at the inlet, where C0 denotes NP concentration within the bolus. At the outflow, a homogeneous Neumann boundary condition was specified. A special Robin-type boundary condition developed by Hossain et al. [16] is prescribed at the lumen–wall interface to account for NP deposition to the vessel wall. The mass flux of particles diffusing through the lumen–wall interface and adhering to the vessel wall is assumed to be a function of particle size dp, local wall shear rate S and probability of adhesion Pa, defined as the probability of having at least one ligand–receptor bond. The parameter Pa can be considered as a measure of particle avidity towards the vessel wall or the strength of adhesion. That is, the larger the value of Pa, the greater is the avidity and strength with which the particle firmly adheres to the wall.

The propensity of a particle to adhere stably to the vessel wall withstanding dislodging hydrodynamic forces is strongly influenced by the physico-chemical properties of the NPs. Accordingly, Decuzzi & Ferrari [43] modelled Pa as a function of physiological parameters such as target receptor density and local wall shear stress (WSS), as well as certain design parameters including particle shape, size, ligand type and density. This particle firm-adhesion model, which has been validated in vitro in a previous work [16] for spherical particles in point contact with the vessel wall, is used herein to account for NP wall deposition. A summary of the modelling details, including the mathematical expressions and parameter values used, is provided in appendix A. For a more comprehensive description of the modelling approach and parameter selection, see [16,44] and references therein.

2.3.1. Solution approach

The governing equations were solved by applying finite-element-based isogeometric analysis [37,45] using quadratic NURBS to describe the exact geometry as well as the solution space [17,24]. A residual-based variational multi-scale method [18] was implemented to solve the system of equations, using a Newton–Raphson procedure with a multi-stage predictor–corrector algorithm applied at each time step. The generalized−α method [46,47], an implicit second-order time-accurate method that is also unconditionally stable, was used for time advancement. Readers are referred to the numerical procedures described in [17,25,45,48,49] for further details.

A portion of the right SFA in a patient affected by PAD has been reconstructed from MR images using a hexahedral solid NURBS model. A representative case is shown in figure 1 where the three-dimensional MRI reconstruction and three cross sections of the SFA lumen and blood vessel wall are displayed. Similar MRI data were extracted from the PAD patient followed-up longitudinally over a period of 24 months. The baseline geometry and the corresponding problem set-up are presented in figure 2, together with the initial and boundary conditions, and the governing equations. The patient-specific mean inflow velocity waveform extracted via PC MRI with a period T of 1 s (heart rate = 60 beats min−1) was imposed at the corresponding SFA inlet assuming a paraboloid-shaped profile with a maximum at the centroid of the vessel inlet cross section and zero values at the boundary. The inflow velocity vectors were oriented normal to the inlet plane. The simulations were run on a computational mesh consisting of 25 992 quadratic NURBS elements (baseline case) for 10 cardiac cycles (10 s total) with a time step of 0.05 s employing the solution strategies described above. Boundary layer meshes were used with the finest boundary element thickness of the order of 10−6 cm for more accurate computation of wall quantities of interest, namely the WSS and OSI. The flow remained laminar throughout the cardiac cycle. The upper bound of the Reynolds number was calculated to be 774 and 1642 for the baseline and the 24-month post-intervention cases, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Blood flow analysis

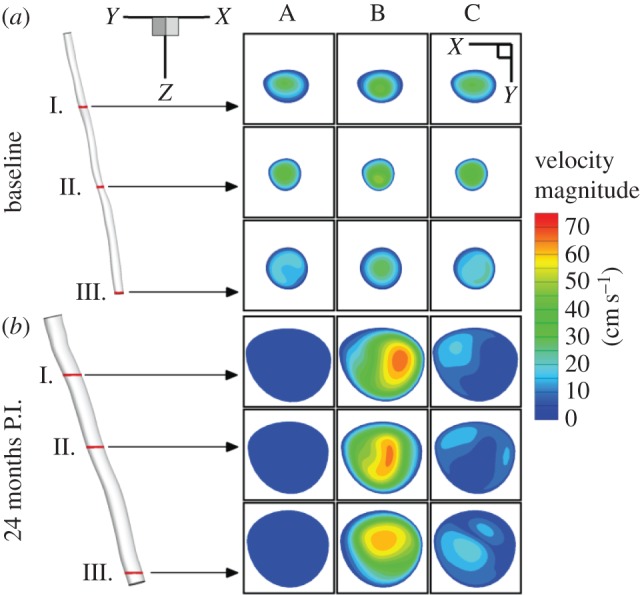

In figure 3, the velocity magnitude is presented for baseline (top) and 24-month post-intervention case at three different cross sections, namely proximal (slice I), distal (slice III) and an intermediate location near the stenosis referred to as ‘mean’ (slice II). In addition, three different times in the cardiac cycle are depicted: (A) end diastole, (B) post-peak systole and (C) end systole. Significant luminal enlargement is observed post intervention because of stent implantation, resulting in a 453%, 313% and 264% increase in cross-sectional area at the stenosis (‘mean’), proximal and distal locations, respectively. It is worth noting that the SFA segment enclosed between the proximal and distal slices represents overlapping regions across follow-up visits. That is, the proximal, mean and distal slices in the baseline case essentially correspond to the same locations in the 24-month post-intervention geometry.

Figure 3.

Blood flow in the SFA. Velocity magnitude is shown for baseline (a) and 24 months post intervention (P.I.) (b) at three different cross sections: (I) proximal, (II) mean and (III) distal. In addition, three different times in the cardiac cycle are presented: end diastole (column A), post-peak systole (column B) and post systole (column C). (Online version in colour.)

At baseline, the velocity magnitude levels seem to drop notably from the proximal to the distal sections consistently during the cardiac cycle because of flow restriction at the stenosis. However, this phenomenon appears to be less pronounced during peak systole (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Mean flow velocity magnitude measured via PC MRI (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2a) also shows markedly decreased values distal to the SFA narrowing. While a tri-phasic flow profile typical of healthy subjects is not preserved above and below the lesion due to the diseased condition, there is no peak delay. On the other hand, because of the implanted stent in the 24-month post-intervention SFA geometry blood flow is no longer restricted, resulting in a 500% increase in peak flow rate (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2b). Consequently, there is less of a variation in velocity magnitude between proximal and distal slices in contrast with the baseline case. It also appears that a bi-phasic waveform is recovered 24 months post intervention (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2c).

In figure 4, the streamlines coloured according to velocity magnitude are depicted for the baseline (top row) and 24-month post-intervention cases. Figure insets represent magnification of the region downstream of the stenosis (‘mean’ slice) at various times during the cardiac cycle as departures from unidirectional flow are known to occur distal to stenosis [50]. The time evolution of the streamline trajectories in figure 4 clearly captures the pulsatile nature of the blood flow. In the baseline case, driven by the inflow condition, the general flow direction reverses between (A) t = 0.2 s and (B) t = 0.4 s as it enters the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle, only to reverse back again during diastole at (C) t = 0.6 s. Slightly after peak systole (B), streamlines downstream of the stenosis appear to be tangled, indicating disturbed flow. Such localized complex flow features are notably absent in the corresponding post-intervention case (see bottom row of figure 4). In fact, streamlines in general appear to be fairly regular post intervention, indicating largely unidirectional flow in the highlighted region. At the advent of the systolic phase (A), there is a hint of change in flow direction as it transitions from the diastolic phase, resulting in a slightly disturbed flow downstream of previous stenosis (the ROI). After peak systole (B), during the downstroke of the systole phase, a reversal of flow occurs. At end systole (C), the streamlines become mildly perturbed as they once again try to adjust to the backflow during the diastolic phase.

Figure 4.

Blood flow in the SFA. Streamlines with colour representing velocity magnitude are presented at baseline (a) and 24 months post intervention (b). Insets provide a closer look at a region downstream from mean cross section (stenosis) at three different times: (A) end systole, (B) post-peak systole and (C) post systole. (Online version in colour.)

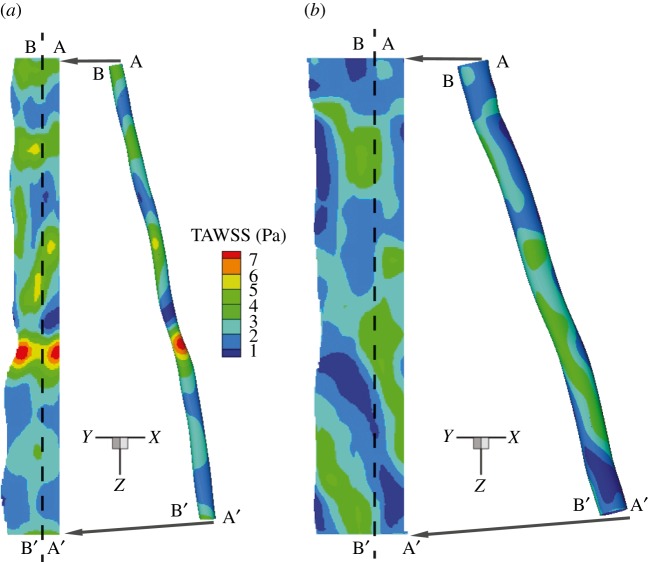

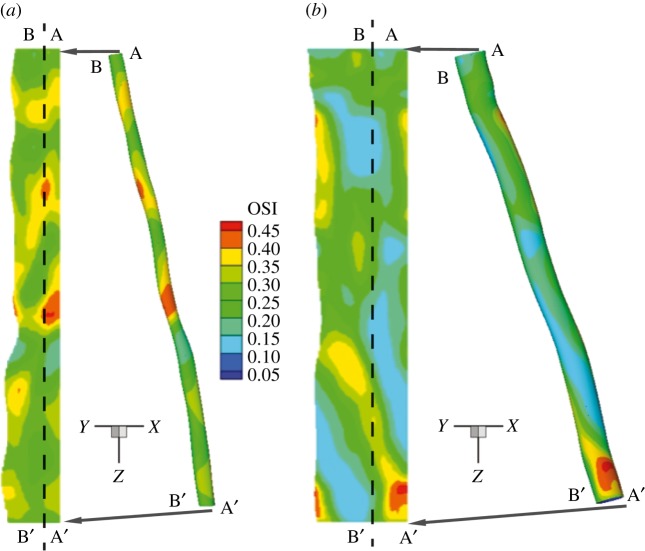

Figures 5 and 6 report the spatial distribution of the TAWSS and OSI, respectively. In the baseline case, alternate areas of lower (less than 1 Pa) and higher (more than 5 Pa) TAWSS regions appear near the stenosis (figure 5). Twenty-four months after stent implantation, relatively lower levels of TAWSS magnitude (less than 5 Pa) are observed that also appear to be more uniformly distributed throughout the SFA segment when compared with the baseline case. Similarly, as a result of a more regularized blood flow in the post-intervention geometry, the distribution pattern and magnitude for the OSI is altered appreciably (figure 6). At 24 months post intervention, OSI levels appear to diminish considerably near the original constriction, in some areas by a factor of 2, when compared with the baseline case. It appears that regions of relatively higher OSI generally correspond to lower WSS values (see electronic supplementary material, figure S3). This seems to be largely the case for the 24-month post-intervention geometry where the flow is essentially unidirectional. Interestingly, in the disturbed flow region downstream of the stenosis in the baseline case, this inverse relationship between the TAWSS and OSI does not seem to hold.

Figure 5.

TAWSS in the SFA. Vascular distribution patterns for TAWSS (a) baseline and (b) 24 months post intervention. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 6.

OSI in the SFA. Vascular distribution patterns for the OSI (a) baseline and (b) 24 months post intervention. (Online version in colour.)

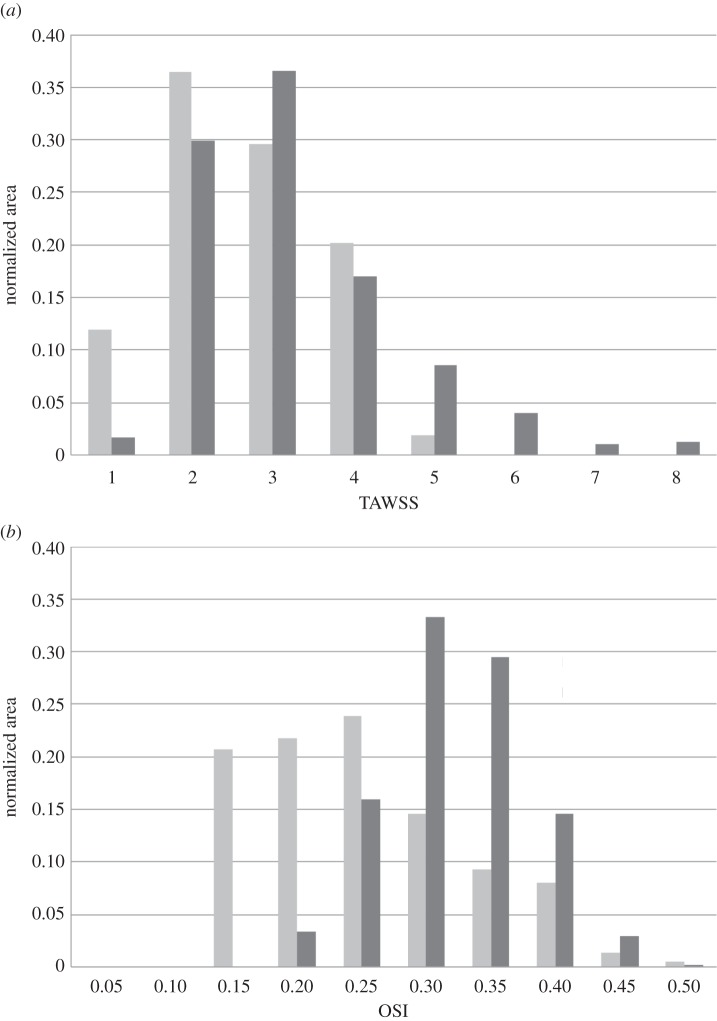

Figure 7a,b shows histograms of TAWSS and OSI distributions, respectively, for both baseline (light grey) and 24-month post-intervention (dark grey) cases. Each bar of the histogram represents the amount of normalized area with a defined range of each quantity of interest. It is worth noting that the x-axis labels denote the upper bound of each range. For example, in figure 7a, the first bar has an x-axis label of ‘1’, indicating that, for the 24-month post-intervention distribution (24 M PI), 12% of the arterial wall area has a TAWSS between the values 0 and 1. The mean, the skewness and the kurtosis [40] of the TAWSS and OSI distributions are presented in the electronic supplementary material, table S1. Mean TAWSS is reduced by 22% from the baseline to the 24-month post-intervention simulations. Baseline TAWSS distribution (figure 7a) has a positive skewness (approx. 1.27), indicating a distribution with an asymmetric tail extending towards more positive (higher TAWSS) values from the mean. This can be attributed to the higher TAWSS values present at the stenosed region at baseline (see figures 5 and 7a). Stent implantation induced a 40% decrease in the maximum TAWSS (from 7 to 4 Pa) value (along with a drop in mean TAWSS), which resulted in a reduced skewness (approx. 0.2319) for the 24-month post-intervention case. OSI levels also diminished post intervention (32% drop in mean OSI), signifying reduced disturbed flow. Additionally, a relatively smaller proportion of the vascular wall area (80% versus 34%) is subjected to higher OSI (more than 2.5) values post intervention (figure 7b). This indicates appreciable improvement in haemodynamics as lower OSI regions are considered less at risk for restenosis [29].

Figure 7.

Distribution of near-wall quantities. (a) TAWSS and (b) OSI distribution in the baseline (dark grey) and 24-month post-intervention (grey) geometry. Each bar of the histograms represents the amount of normalized area with a defined range of the respective quantity. Note, the x-axis labels denote the upper bound of each range.

3.2. Predicting the vascular deposition of nanoparticles in the superficial femoral artery

Next, the computational tool is used to predict the wall deposition patterns in a simulation of systemically injected NPs in the pre- and post-intervention SFA to explore possible use of nanomedicine in the non-invasive imaging and treatment of PAD patients. It should be emphasized here that, although the same patient-specific data as for ELIMIT have been used, no patients in this clinical trial received an NP injection. In the in silico simulations, spherical NPs (dp = 100 nm) were introduced directly into the bloodstream from a bolus of NPs located at the inlet of the artery segment. Assuming that the receptors are uniformly distributed throughout the entire vessel wall with a uniform surface density, flow-coupled particle transport simulations were run for 10 cardiac cycles following the methodology outlined in the Material and methods section to quantify particle adsorption to the arterial wall. Figure 8 shows the resulting wall deposition pattern of NPs under such non-specific targeting for both baseline and 24-month post-intervention cases. A distinctively inhomogeneous distribution of NPs is observed in the baseline case (figure 8a) where the vast majority of the particles appear to accumulate near the source with NP surface density gradually decreasing in the downstream direction. Because of the restricted blood flow near the constriction and the resulting increased proportion of backflow during the cardiac cycle, the NPs struggle to move past the stenosis (electronic supplementary material, figure S4). The NPs therefore largely remain confined upstream of the stenosis throughout the simulation. Conversely, a much more homogeneous distribution of particles is observed in the 24-month follow-up case. This can be mostly attributed to the significantly greater particle availability downstream compared with the baseline case (as evidenced by the number of NPs leaving the SFA outlet, which increases by a factor of approx. 260). From electronic supplementary material, figure S5, it takes the NPs roughly three cardiac cycles to fill up the entire SFA segment, while failing to do the same (i.e. saturating the blood with particles) in the baseline case, even after 10 cardiac cycles.

Figure 8.

Vascular deposition of NPs—uniform receptor density. Spatial distribution patterns for 100 nm spherical NPs adhering on the SFA, expressing a uniform surface density of vascular receptors. The two images are for (a) baseline and (b) 24 months post intervention. The surface density of adhered NPs (#/cm2) is calculated at t = 10 s, where the NPs were injected for 10 cardiac cycles (10 s) from a bolus placed at the SFA inlet. (Online version in colour.)

In order to gain further insights into disease management, we explored how surface-functionalized NPs would fare when specifically targeting inflammation, a precursor to many diseases including atherosclerosis. To that end, the vessel wall deposition of cell adhesion molecule (CAM)-directed particles was investigated. These CAMs, in particular VCAM-1, are regarded as early markers of atherosclerosis due to their upregulation at the site of inflammation. First, a phenomenological model (see appendix A) correlating CAM expression to local WSS as detailed in [16,44,51] was used to estimate the surface density of the target receptor with respect to their unstimulated expression under static conditions (see electronic supplementary material, figure S6). Spherical NPs (dp = 100 nm) uniformly coated with anti-VCAM-1 antibodies (aVCAM-1 NPs) were then introduced into the bloodstream by placing a bolus of NPs at the SFA inlet as before. Carried by the blood flow, these NPs can recognize VCAM-1 expression and firmly adhere to the vessel wall through ligand–receptor bond formation. Once again, flow-coupled particle transport simulations were carried out for 10 cardiac cycles. The resulting spatial distribution of NPs in terms of particle surface density (cm−2) is presented in figure 9a,b for the baseline and 24-month post-intervention cases, respectively. In addition to local haemodynamics, receptor surface density appears to modulate particle adhesion, resulting in a spatially inhomogeneous particle distribution pattern in both cases. That is, the higher the receptor density and higher the OSI, the greater the particle concentration at a given site. From figure 9, aVCAM-1 NPs appear to preferentially accumulate near the diseased region in the baseline case, which is encouraging from a therapeutic (and also diagnostic) perspective as this may potentially translate to a higher drug/imaging agent concentration in the targeted area (i.e. the stenosis). Conversely, the same NPs appear to adhere less in the 24-month post-intervention case, resulting in a 47% decrease in mean surface density.

Figure 9.

Vascular deposition of NPs—non-uniform receptor density. Spatial distribution patterns for 100 nm spherical NPs adhering on the SFA, expressing a non-uniform surface density of VCAM-1 molecules. The two images are for (a) baseline and (b) 24 months post intervention. The surface density of adhered NPs (#/cm2) is calculated at t = 10 s, where the NPs were injected in a simulation for 10 cardiac cycles (10 s) from a bolus placed at the SFA inlet. The surface density of VCAM-1 molecules is calculated as a function of the wall shear rates. (Online version in colour.)

In a similar vein, ICAM-1- and E-selectin-targeted particle distributions were investigated (electronic supplementary material, figures S7 and S8). The mean surface densities for the aICAM-1 and aEsel NPs in the baseline case were estimated to be 1.544 × 10−6 cm−2 and 2.85 × 10−6 cm−2, respectively. aICAM-1 NPs accumulate least efficiently near the constriction when compared with the aVCAM-1 and aEsel NPs. The latter seems to achieve a more uniform distribution than the aVCAM-1- and aICAM-1-coated particles. Interestingly, the E-selectin-directed particles appear to have better targeting in the baseline case, that is, they have the highest concentration in the most severely diseased (narrowest) part of the SFA, thereby making them viable candidates for local drug delivery systems that use NPs as drug carriers to diffuse atherosclerosis [37]. Much like the aVCAM-1 NPs, both aICAM-1 and aEsel particles adhere less in the 24-month post-intervention geometry, resulting in a 52% and 50% reduction in mean surface density, respectively. aVCAM-1, aICAM-1 and aEsel NP distributions are presented in the electronic supplementary material, figure S9.

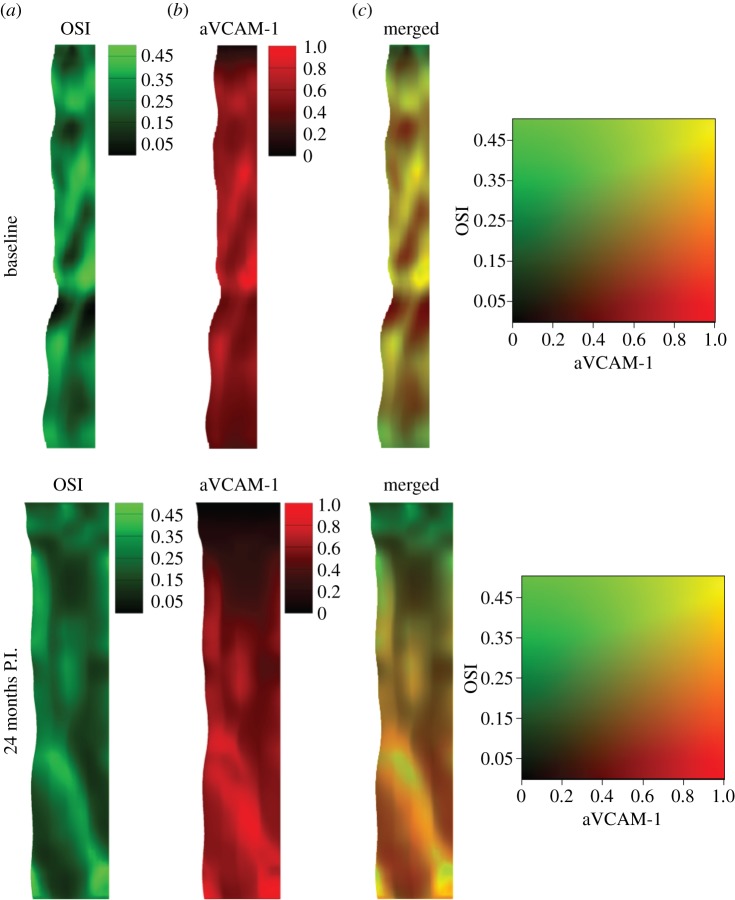

In order to investigate possible spatial correlation between local haemodynamics and NP adhesion, the OSI and aVCAM-1 NP distribution colour maps were merged for the baseline and 24-month post-intervention cases (figure 10). Qualitatively, there appears to be a strong spatial correlation between the two quantities throughout the computational domain, except for small areas very close to the inlet and outlet boundaries. Generally, regions of high OSI are associated with regions of greater aVCAM-1 deposition. In a similar qualitative comparison made between the TAWSS and aVCAM-1 (electronic supplementary material, figure S10), the spatial correlations are not as evident, especially in the baseline case. In regions downstream of the stenosis, the aVCAM-1 NP deposition seems to follow the pattern of high OSI values rather than that of low TAWSS values. RRT values also show strong spatial correlation with aVCAM-1 surface density (electronic supplementary material, figure S11). RRT, which combines both the OSI and WSS, appears to perform better than TAWSS in predicting NP deposition, especially in the baseline case.

Figure 10.

Spatial correlation between local haemodynamics and NP adhesion. Two different contours, (a) OSI and (b) aVCAM-1 concentration (normalized), are merged (c) for both baseline (top) and 24-month post-intervention (bottom) configurations. Here, the unrolled geometries are presented.

There are a few limitations and possible extensions to this work. Although any error is undesirable, in all practical sense they are unavoidable when simulating patient-specific haemodynamics. This is particularly true in the absence of a measured three-component velocity profile prescribed at the inlet [52–55], as realistic three-dimensional inflow velocity boundary conditions can potentially amplify three-dimensional bulk flow structures [53] and promote particle transport [56]. In these limiting cases, different strategies of applying MRI measured flow data as boundary conditions can be implemented. At their simplest, inflow boundary conditions can be imposed by choosing a priori velocity profiles under a fully developed flow assumption: (a) Womersley's profile derived from analytical solutions [57], (b) parabolic profile, or (c) blunt profile [58]. In such a case, the accuracy of the numerical solution is impacted by the choice of velocity profile. While mean WSS distributions are expected to be qualitatively similar, this approach in general has been shown to influence oscillating WSS [54]. Alternative strategies include the augmented formulation of the flow problem using Lagrangian multipliers [59,60] and other subsequent improvements [61,62]. However, some of these approaches can be computationally expensive and difficult to discretize, potentially posing additional challenges.

For simplicity, a fully developed inflow profile was assumed in this work. This may not be the case as the truncated segment upstream may be not straight enough, containing undeveloped velocity profiles. However, if placed sufficiently far upstream of the ROI, as it was in this study, the influence (or ‘memory’) of the inlet velocity profile should be essentially lost [63]. The specific choice of a paraboloid-shaped velocity profile, a reasonable assumption that has been widely used in previous computational fluid dynamics studies [40,64,65], was made considering the following observations. Given the alternative Womersley profile's complexity of implementation and minimal, if any, superiority in haemodynamic accuracy over other inlet velocity profiles, its use might not be necessary in many cases [66–68]. Campbell et al. [58] have recently shown that the difference in errors produced by the parabolic velocity profile and the Womersley profile was not statistically significant most of the time. In cases where an assumption must be made, a pulsatile parabolic profile was recommended over the blunt or Womersley profiles as it produced the lowest magnitude of error in the WSS and OSI. The Wormersley number in those cases was in a similar range as in this work (approx. 4 in the baseline case for example). It was further contended that both these haemodynamic metrics are affected more by variation in three-dimensional vessel geometry (geometric factors such as curvature of the vessel) among patients [66–68], which is the main objective of this work and a planned future study. In addition, using the subject's own flow waveform over a non-specific (generalized) waveform leads to more accurate results [58]. Hence, prioritizing an accurate reconstruction of vessel anatomy and acquisition of the subject's own flow waveform over selecting the perfect velocity profile appears to be a reasonable approach.

Another limitation of this is the rigid wall approximation. This simplifying assumption can lead to an overestimation of local WSS [69], especially when there is significant vessel curvature or a bifurcation. However, as demonstrated by Kim et al. [70] in a previous study on a compliant SFA with bifurcation, bulk flow quantities are generally insensitive to wall motion. While minor changes (less than 25%) in the OSI and TAWSS were reported in select areas like bifurcations, it was concluded that wall compliance did not significantly influence these quantities [70]. In light of the above findings, the rigid wall assumption was deemed reasonable as a first approximation for the single-branch SFA geometry under consideration [63].

Due to lack of suitable data, the stent struts were not explicitly modelled in our simulation of the 24-month post-intervention case, which can alter the local haemodynamics as previously observed by Chiastra et al. [40]. This limitation of our approach might have led to an underestimation of per cent area exposed to lower WSS (i.e. atheroprone regions), thus potentially affecting our prediction of NP deposition pattern in the post-intervention case. Additionally, the precise identification of anatomical markers, and consequently the determination of overlapping SFA regions across the two MRI scan time points (baseline and 24 months post intervention) were subject to usual human error [15].

Planned future work includes the application of the presented analysis framework to investigate a larger population of PAD patients. Longitudinal studies averaging multiple patient-specific models over time can better elucidate relationships between haemodynamics and atherosclerosis progression (and regression). Additional topics that might be of interest include geometric characterization of pre- and post-intervention geometries (vascular segment curvature, torsion and so forth) in multiple patients [71] to investigate, and potentially establish, relationships between various geometric factors and disturbed flow to gain further insight in PAD management. Extending the current model to include vessel compliance along with more realistic outflow boundary conditions is also planned [72,73]. Furthermore, as vascular expression of CAMs is known to be sensitive to the temporal gradient of WSS [74], which can potentially influence CAM-targeted NP deposition patterns, it would be interesting to carry out a systematic analysis of this important quantity at critical geometric locations (e.g. recirculation zones distal to the stenosis) [50]. Additionally, extending the current analysis to the intermediate time points (six and 12 months) to investigate if any of the detected haemodynamic improvements occurred earlier in the post-operative process could provide important insights into PAD management.

4. Conclusion

An isogeometric analysis framework has been used to predict the blood flow and vascular deposition in a simulation of systemically injected nanomedicines into the SFA of a PAD patient. Upon intervention, a dramatic improvement in blood flow dynamics has been documented by the in silico simulations showing a 32% reduction in OSI and an approximate 500% increase in overall peak blood flow rate. Also, it has been observed that systemically injected nanomedicines, targeted to inflammatory vascular molecules such as VCAM-1, E-selectin and ICAM-1, would preferentially accumulate near the stenosis in the baseline configuration. In particular, for the VCAM-1-targeted 100 nm NPs, the vascular accumulation has shown a maximum at the stenosis with a surface density up to 1.9 times higher than the mean. This high, specific vascular accumulation could be effectively used for the detection and treatment of plaques forming in the SFA. The development of accurate image-guided patient-specific predictive tools, such as the isogeometric analysis framework presented here, can help in assessing disease burden and monitor progression/regression of atherosclerosis in response to therapeutic and interventional treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Travis Sanders for his assistance with data post-processing and Benjamin Urick for generating the artwork in figure 2.

Appendix A

A.1. The flow problem

The strong form of the continuity and momentum balance equations in the fluid domain Ω with its boundary Γ divided into three non-overlapping parts, the inflow (Γin) and outflow (Γout) boundaries and the vascular wall (Γs), are as follows:

| A 1 |

| A 2 |

| A 3 |

| A 4 |

| A 5 |

| A 6 |

where x is a point in the spatial domain Ω and t is a point in the time domain [0, T]. In these equations, u(x; t) represents the fluid velocity vector, p(x; t) the pressure, f the external body force, n the unit outward normal to the surface, denoted Γ, and u0(x; 0) the initial velocity vector. An inflow velocity vector g(x; t) was specified at the inlet (Γin), a no-slip boundary condition (equation (A 4)) was prescribed at the rigid and impermeable vascular wall (Γs) and a traction-free outflow boundary condition (equation (A 5)) was implemented at the branch outlet (Γout).

A.2. The mass-transport problem

In the strong form, the transport problem can be stated as

| A 7 |

| A 8 |

| A 9 |

| A 10 |

| A 11 |

where C(x; t) is the particle concentration, K is the diffusivity tensor and σ is the reaction coefficient. At the inlet (particle injection site) Γin, a Dirichlet boundary condition is prescribed (equation (A 8)) where C0 is the particle concentration at the inlet. At the outflow Γout, a homogeneous Neumann boundary condition was specified (equation (A 9)); and a Robin-type boundary condition (equation (A 10)) was prescribed at the rigid wall interface (Γs), where the normal component of the flux of particles ‘diffusing’ out of the fluid domain Ω and adhering to the vessel wall Γs is assumed to be directly influenced by the local wall shear rate S, the particle diameter dp, and the probability of adhesion Pa, as follows (figure 2):

| A 12 |

Here, dφ/dt is the rate of NP accumulation within the vessel wall with φ denoting the NP surface density.

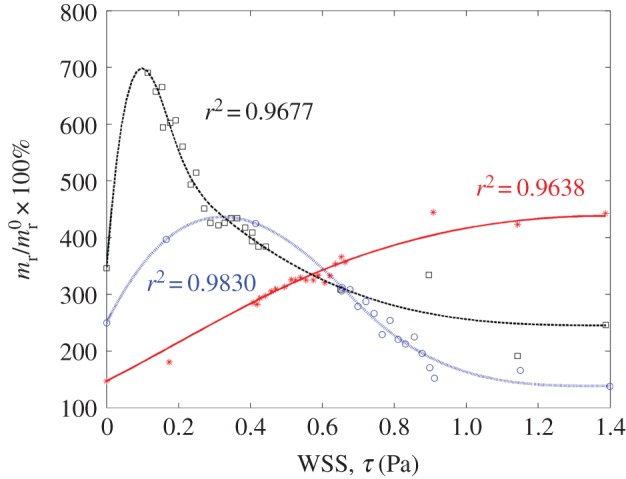

Figure 11.

Receptor surface density versus WSS relationship determined by curve fitting to in vitro data for TNF-α stimulated CAM expression, obtained from [51]. Here, stars, squares and circles denote experimental data for ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin, respectively, and the solid lines represent the corresponding fitted data. The respective CAM (receptor) surface density mr is reported as per cent (%) of unstimulated CAM expression under static conditions  . Addition of TNF-α under static conditions stimulated upregulation of VCAM-1 by 350%, ICAM-1 by 150% and E-selectin by 250% [44]. (Online version in colour.)

. Addition of TNF-α under static conditions stimulated upregulation of VCAM-1 by 350%, ICAM-1 by 150% and E-selectin by 250% [44]. (Online version in colour.)

The parameter Pa for a spherical particle in point contact with the vessel wall can be expressed as

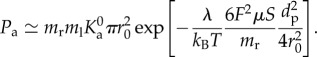

|

A 13 |

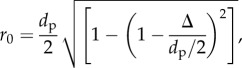

Here, ml is the uniform surface density of ligand molecules decorating the NP surface that can specifically interact with counter molecules (receptors) expressed on the vessel wall with a surface density mr (figure 11).  is an affinity constant characterizing the molecular interaction between ligands and receptors at zero mechanical load, λ is a characteristic length of the ligand–receptor bond typically of the order of 0.1 to 1 nm; kBT is the Boltzmann thermal energy ( = 4.142 × 10−21 J); Fs ( = 1.668) is the coefficient of hydrodynamic drag force on the spherical particle; μS is the WSS; and r0 is the radius of adhesion defined as

is an affinity constant characterizing the molecular interaction between ligands and receptors at zero mechanical load, λ is a characteristic length of the ligand–receptor bond typically of the order of 0.1 to 1 nm; kBT is the Boltzmann thermal energy ( = 4.142 × 10−21 J); Fs ( = 1.668) is the coefficient of hydrodynamic drag force on the spherical particle; μS is the WSS; and r0 is the radius of adhesion defined as

|

A 14 |

with Δ being the separation distance between the particle and the substrate, at equilibrium (i.e. firm particle adhesion). The selected parameters are listed in table 1. For a more comprehensive discussion, readers are referred to [16].

Table 1.

Particle adhesion parameters used in the simulation [16].

| parameter | value |

|---|---|

| surface density of ligand molecules | ml = 1015 #/m2 |

| surface density of receptor molecules | mr = 1013 #/m2 |

| ligand–receptor affinity constant at zero load |

= 2.3 × 10−17 m2 = 2.3 × 10−17 m2

|

| characteristic length of ligand–receptor bond | λ = 1 × 10−10 m |

| dynamic viscosity of water | μ = 0.001 N-s m−2 |

| drag coefficient on the spherical particle | Fs = 1.668 |

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas through grant no. CPRIT RP110262, and through grants from the National Institutes of Health (USA) (NIH) U54CA143837 and U54CA151668. The additional support for S.S.H. and T.J.R.H. from the Portuguese CoLab grant no. UTA06-894 is also gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Lumsden AB, Rice TW, Chen C, Zhou W, Lin PH, Bray P, Morrisett J, Nambi V, Ballantyne C. 2007. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease: magnetic resonance imaging and the role of aggressive medical management. World J. Surg. 31, 695–704. ( 10.1007/s00268-006-0732-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, Feigelson HS, Klauber MR, McCann TJ, Browner D. 1992. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 326, 381–386. ( 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR, Coll JR, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Hirsch AT. 2008. The impact of peripheral arterial disease on health-related quality of life in the peripheral arterial disease awareness, risk, and treatment: new resources for survival (PARTNERS) program. Vasc. Med. 13, 15–24. ( 10.1177/1358863X07084911) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nehler MR, McDermott MM, Treat-Jacobson D, Chetter I, Regensteiner JG. 2003. Functional outcomes and quality of life in peripheral arterial disease: current status. Vasc. Med. 8, 115–126. ( 10.1191/1358863x03vm483ra) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeRubertis BG, et al. 2007. Shifting paradigms in the treatment of lower extremity vascular disease: a report of 1000 percutaneous interventions. Ann. Surg. 246, 415–422; discussion 22–24 ( 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31814699a2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Aikawa M. 2002. Stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques: new mechanisms and clinical targets. Nat. Med. 8, 1257–1262. ( 10.1038/nm1102-1257) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby P, Aikawa M, Jain MK. 2006. Vascular endothelium and atherosclerosis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2006, 285–306. ( 10.1007/3-540-36028-X_9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn C, Schwartz MA. 2009. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 53–62. ( 10.1038/nrm2596) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prosi M, Perktold K. 2006. Computer simulation of coupled luminal and transmural mass transport processes in a carotid bifurcation model. J. Biomech. 39, S376 ( 10.1016/S0021-9290(06)84514-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Formaggia L, Quarteroni AM, Veneziani A. 2009. Cardiovascular mathematics. Milan, Italy: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinman DA, Vorp DA, Ethier CR. 2003. Computational modeling of arterial biomechanics: insights into pathogenesis and treatment of vascular disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 37, 1118–1128. ( 10.1067/mva.2003.122) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada S, Karino T. 2000. Computational study on LDL transfer from flowing blood to arterial walls. In Clinical application of computational mechanics to the cardiovascular system (ed. T Yamaguchi), pp. 157–173. Tokyo, Japan: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caro CG. 2009. Discovery of the role of wall shear in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 158–161. ( 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166736) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peiffer V, Sherwin SJ, Weinberg PD. 2013. Does low and oscillatory wall shear stress correlate spatially with early atherosclerosis? A systematic review. Cardiovasc. Res. 99, 242–250. ( 10.1093/cvr/cvt044) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor CA, Figueroa CA. 2009. Patient-specific modeling of cardiovascular mechanics. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 11, 109–134. ( 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160521) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hossain SS, Zhang Y, Liang X, Hussain F, Ferrari M, Hughes TJR, Decuzzi P. 2012. In silico vascular modeling for personalized nanoparticle delivery. Nanomedicine 8, 343–357. ( 10.2217/nnm.12.124) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes TJR, Cottrell JA, Bazilevs Y. 2005. Isogeometric analysis: CAD, finite elements, NURBS, exact geometry and mesh refinement. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 194, 4135–4195. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2004.10.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazilevs Y, Calo VM, Cottrell JA, Hughes TJR, Reali A, Scovazzi G. 2007. Variational multiscale residual-based turbulence modeling for large eddy simulation of incompressible flows. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 197, 173–201. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2007.07.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hossain SS, Kopacz AM, Zhang Y, Lee S-Y, Lee T-R, Ferrari M, Hughes TJR, Liu WK, Decuzzi P. 2013. Multiscale modeling for the vascular transport of nanoparticles. In Nano and cell mechanics (eds HD Espinosa, G Bao), pp. 437–459. Oxford, UK: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hossain SS, Zhang Y. 2013. Application of isogeometric analysis to simulate local nanoparticulate drug delivery in patient-specific coronary arteries. In Multiscale simulations and mechanics of biological materials (eds S Li, D Qian), pp. 149–167. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leuprecht A, Perktold K. 2001. Computer simulation of non-Newtonian effects on blood flow in large arteries. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 4, 149–163. ( 10.1080/10255840008908002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Vignon-Clementel IE, Coogan JS, Figueroa CA, Jansen KE, Taylor CA. 2010. Patient-specific modeling of blood flow and pressure in human coronary arteries. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 3195–3209. ( 10.1007/s10439-010-0083-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE. 2014. Fluid–structure interaction modeling of patient-specific cerebral aneurysms. In Visualization and simulation of complex flows in biomedical engineering (eds R Lima, Y Imai, T Ishikawa, MSN Oliveira), pp. 25–45. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Bazilevs Y, Goswami S, Bajaj CL, Hughes TJR. 2007. Patient-specific vascular NURBS modeling for isogeometric analysis of blood flow. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 196, 2943–2959. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2007.02.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossain SS. 2009. Mathematical modeling of coupled drug and drug-encapsulated nanoparticle transport in patient-specific coronary artery walls. Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bazilevs Y, Michler C, Calo VM, Hughes TJR. 2010. Isogeometric variational multiscale modeling of wall-bounded turbulent flows with weakly enforced boundary conditions on unstretched meshes. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 199, 780–790. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2008.11.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calo VM, Bazilevs Y, Hughes TJR, Moser R. 2010. Turbulence modeling for large eddy simulations. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 199, 779 ( 10.1016/j.cma.2009.09.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bao G, et al. 2014. USNCTAM perspectives on mechanics in medicine. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140301 ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.0301) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fayad ZA, Fuster V, Nikolaou K, Becker C. 2002. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for noninvasive coronary angiography and plaque imaging: current and potential future concepts. Circulation 106, 2026–2034. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034392.34211.FC) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunner G, et al. 2013. The effect of lipid modification on peripheral artery disease after endovascular intervention trial (ELIMIT). Atherosclerosis 231, 371–377. ( 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markl M, et al. 2003. Time-resolved three-dimensional phase-contrast MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 17, 499–506. ( 10.1002/jmri.10272) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geiger J, Markl M, Jung B, Grohmann J, Stiller B, Langer M, Arnold R. 2011. 4D-MR flow analysis in patients after repair for tetralogy of Fallot. Eur. Radiol. 21, 1651–1657. ( 10.1007/s00330-011-2108-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah DJ, Brown B, Kim RJ, Grizzard JD. 2007. Magnetic resonance evaluation of peripheral arterial disease. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 15, 653–679. ( 10.1016/j.mric.2007.08.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. 671 NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2089) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tagliasacchi A, Alhashim I, Olson M, Zhang H. 2012. Mean curvature skeletons. Comput. Graph. Forum 31, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bezdek JC, Hathaway RJ. 2003. Convergence of alternating optimization. Neural Parallel Sci. Comput. 11, 351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hossain S, Hossainy S, Bazilevs Y, Calo V, Hughes T. 2012. Mathematical modeling of coupled drug and drug-encapsulated nanoparticle transport in patient-specific coronary artery walls. Comput. Mech. 49, 213–242. ( 10.1007/s00466-011-0633-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He X, Ku DN. 1996. Pulsatile flow in the human left coronary artery bifurcation: average conditions. J. Biomech. Eng. 118, 74–82. ( 10.1115/1.2795948) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor CA, Hughes TJR, Zarins CK. 1998. Finite element modeling of three-dimensional pulsatile flow in the abdominal aorta: relevance to atherosclerosis. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 26, 975–987. ( 10.1114/1.140) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiastra C, Morlacchi S, Gallo D, Morbiducci U, Cárdenes R, Larrabide I, Migliavacca F. 2013. Computational fluid dynamic simulations of image-based stented coronary bifurcation models. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20130193 ( 10.1098/rsif.2013.0193) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olgac U, Poulikakos D, Saur SC, Alkadhi H, Kurtcuoglu V. 2009. Patient-specific three-dimensional simulation of LDL accumulation in a human left coronary artery in its healthy and atherosclerotic states. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296, H1969–H1982. ( 10.1152/ajpheart.01182.2008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stangeby DK, Ethier CR. 2002. Computational analysis of coupled blood-wall arterial LDL transport. J. Biomech. Eng. 124, 1–8. ( 10.1115/1.1427041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. 2006. The adhesive strength of non-spherical particles mediated by specific interactions. Biomaterials 27, 5307–5314. ( 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hossain SS, Hughes TJR, Decuzzi P. 2014. Vascular deposition patterns for nanoparticles in an inflamed patient-specific arterial tree. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 13, 585–597. ( 10.1007/s10237-013-0520-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bazilevs Y, Calo VM, Zhang Y, Hughes TJR. 2006. Isogeometric fluid–structure interaction analysis with applications to arterial blood flow. Comput. Mech. 38, 310–322. ( 10.1007/s00466-006-0084-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung J, Hulbert GM. 1993. A time integration algorithm for structural dynamics with improved numerical dissipation: the generalized method. J. Appl. Mech. 60, 371–375. ( 10.1115/1.2900803) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jansen KE, Whiting CH, Hulbert GM. 2000. A generalized-[alpha] method for integrating the filtered Navier–Stokes equations with a stabilized finite element method. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 190, 305–319. ( 10.1016/S0045-7825(00)00203-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bazilevs Y, da Veiga LB, Cottrell JA, Hughes TJR, Sangalli G. 2006. Isogeometric analysis: approximation, stability and error estimates for h-refined meshes. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 16, 1031–1090. ( 10.1142/S0218202506001455) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cottrell JA, Hughes TJR, Reali A. 2007. Studies of refinement and continuity in isogeometric structural analysis. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 196, 4160–4183. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2007.04.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White CR, Frangos JA. 2007. The shear stress of it all: the cell membrane and mechanochemical transduction. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 362, 1459–1467. ( 10.1098/rstb.2007.2128) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsou JK, Gower RM, Ting HJ, Schaff UY, Insana MF, Passerini AG, Simon SI. 2008. Spatial regulation of inflammation by human aortic endothelial cells in a linear gradient of shear stress. Microcirculation 15, 311–323. ( 10.1080/10739680701724359) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Favier V, Taylor CA. 2002. Image-based computational modeling of blood flow in a porcine aorta bypass graft. Center for Turbulence Research Annual Research Briefs. See http://ctr.stanford.edu/ResBriefs02/favier.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morbiducci U, Ponzini R, Gallo D, Bignardi C, Rizzo G. 2013. Inflow boundary conditions for image-based computational hemodynamics: impact of idealized versus measured velocity profiles in the human aorta. J. Biomech. 46, 102–109. ( 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.10.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wake AK, Oshinski JN, Tannenbaum AR, Giddens DP. 2009. Choice of in vivo versus idealized velocity boundary conditions influences physiologically relevant flow patterns in a subject-specific simulation of flow in the human carotid bifurcation. J. Biomech. Eng. 131, 021013 ( 10.1115/1.3005157) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Onishi Y, Aoki K, Amaya K, Shimizu T, Isoda H, Takehara Y, Sakahara H, Kosugi T. 2013. Accurate determination of patient-specific boundary conditions in computational vascular hemodynamics using 3D cine phase-contrast MRI. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 29, 1089–1103. ( 10.1002/cnm.2562) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu X, Fan Y, Deng X. 2010. Effect of spiral flow on the transport of oxygen in the aorta: a numerical study. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 917–926. ( 10.1007/s10439-009-9878-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Womersley JR. 1955. Method for the calculation of velocity, rate of flow and viscous drag in arteries when the pressure gradient is known. J. Physiol. 127, 553–563. ( 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005276) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campbell IC, Ries J, Dhawan SS, Quyyumi AA, Taylor WR, Oshinski JN. 2012. Effect of inlet velocity profiles on patient-specific computational fluid dynamics simulations of the carotid bifurcation. J. Biomech. Eng. 134, 051001 ( 10.1115/1.4006681) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Formaggia L, Gerbeau J-F, Nobile F, Quarteroni A. 2001. On the coupling of 3D and 1D Navier–Stokes equations for flow problems in compliant vessels. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 191, 561–582. ( 10.1016/S0045-7825(01)00302-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Veneziani A, Vergara C. 2005. Flow rate defective boundary conditions in haemodynamics simulations. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 47, 803–816. ( 10.1002/fld.843) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Formaggia L, Veneziani A, Vergara C. 2010. Flow rate boundary problems for an incompressible fluid in deformable domains: formulations and solution methods. Comput. Method. Appl. Mech. Eng. 199, 677–688. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2009.10.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Formaggia L, Veneziani A, Vergara C. 2008. A new approach to numerical solution of defective boundary value problems in incompressible fluid dynamics. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 46, 2769–2794. ( 10.1137/060672005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor CA, Steinman DA. 2010. Image-based modeling of blood flow and vessel wall dynamics: applications, methods and future directions. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 1188–1203. ( 10.1007/s10439-010-9901-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolachalama VB, Levine EG, Edelman ER. 2009. Luminal flow amplifies stent-based drug deposition in arterial bifurcations. PLoS ONE 4, e8105 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0008105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van der Giessen AG, Groen HC, Doriot P-A, De Feyter PJ, Van der Steen AF, Van de Vosse FN, Wentzel JJ, Gijsen FJH. 2011. The influence of boundary conditions on wall shear stress distribution in patients specific coronary trees. J. Biomech. 44, 1089–1095. ( 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moyle KR, Antiga L, Steinman DA. 2006. Inlet conditions for image-based CFD models of the carotid bifurcation: is it reasonable to assume fully developed flow? J. Biomech. Eng. 128, 371–379. ( 10.1115/1.2187035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marzo A, Singh P, Reymond P, Stergiopulos N, Patel U, Hose R. 2009. Influence of inlet boundary conditions on the local haemodynamics of intracranial aneurysms. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 12, 431–444. ( 10.1080/10255840802654335) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Myers JG, Moore JA, Ojha M, Johnston KW, Ethier CR. 2001. Factors influencing blood flow patterns in the human right coronary artery. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29, 109–120. ( 10.1114/1.1349703) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Torii R, Keegan J, Wood NB, Dowsey AW, Hughes AD, Yang G-Z, Firmin DN, Thom SAMcG, Xu XY. 2009. The effect of dynamic vessel motion on haemodynamic parameters in the right coronary artery: a combined MR and CFD study. Br. J. Radiol. 82, S24–S32. ( 10.1259/bjr/62450556) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim Y-H, Kim J-E, Ito Y, Shih A, Brott B, Anayiotos A. 2008. Haemodynamic analysis of a compliant femoral artery bifurcation model using a fluid structure interaction framework. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 36, 1753–1763. ( 10.1007/s10439-008-9558-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee S-W, Antiga L, Spence JD, Steinman DA. 2008. Geometry of the carotid bifurcation predicts its exposure to disturbed flow. Stroke 39, 2341–2347. ( 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510644) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vignon-Clementel IE, Alberto Figueroa C, Jansen KE, Taylor CA. 2006. Outflow boundary conditions for three-dimensional finite element modeling of blood flow and pressure in arteries. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 195, 3776–3796. ( 10.1016/j.cma.2005.04.014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grinberg L, Karniadakis GE. 2008. Outflow boundary conditions for arterial networks with multiple outlets. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 36, 1496–1514. ( 10.1007/s10439-008-9527-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ku D, Giddens D, Zarins C, Glagov S. 1985. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 5, 293–302. ( 10.1161/01.ATV.5.3.293) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.