Abstract

Naphthalene has been shown to be a weak carcinogen in rats. To investigate its mechanism of metabolic activation and cancer initiation, mice were topically treated with naphthalene or one of its metabolites, 1-naphthol, 1,2-dihydrodiolnaphthalene (1,2-DDN), 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene (1,2-DHN), and 1,2-naphthoquinone (1,2-NQ). After 4 h, the mice were sacrificed, the treated skin was excised, and the depurinating and stable DNA adducts were analyzed. The depurinating adducts were identified and quantified by ultraperformance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, whereas the stable adducts were quantified by 32P-postlabeling. For comparison, the stable adducts formed when a mixture of the four deoxyribonucleoside monophosphates was treated with 1,2-NQ or enzyme-activated naphthalene were also analyzed. The depurinating adducts 1,2-DHN-1-N3Ade and 1,2-DHN-1-N7Gua arise from reaction of 1,2-NQ with DNA. Similarly, the major stable adducts appear to derive from the 1,2-NQ. The depurinating DNA adducts are, in general, the most abundant. Therefore, naphthalene undergoes metabolic activation to the electrophilic ortho-quinone, 1,2-NQ, which reacts with DNA to form depurinating adducts. This is the same mechanism as other weak carcinogens, such as the natural and synthetic estrogens, and benzene.

Keywords: Naphthalene; Depurinating naphthalene–DNA adducts; Stable naphthalene–DNA adducts; Metabolic activation of naphthalene; 1,2-Naphthalene quinone ultimate carcinogenic metabolite

Introduction

Naphthalene is a component of coal tar products and moth repellents. It is used extensively in the production of plasticizers, resins, insecticides, and surface-active agents [1]. It is a ubiquitous pollutant found mainly in ambient air and to a minor extent in effluent water. The major contributor of naphthalene in air is fossil fuel combustion, but a significant amount is also released as a pyrolytic product of mainstream and side-stream tobacco smoke. Naphthalene was found in nearly 40% of human fat samples [2] and 75% of human breast milk samples [3]. These facts indicate that the population of the United States is exposed to naphthalene, which is included as one of 189 hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 (Title III) of the Environmental Protection Agency [4].

Chronic inhalation of naphthalene (10 or 30 ppm) by mice led to diverse effects, including inflammation of the nose, metaplasia of the olfactory epithelium, and hyperplasia of the respiratory epithelium [5–7]. No neoplastic effects in male mice were found, but female mice showed a slight increase in alveolar/bronchiolar adenomas and carcinomas at the highest exposure level. More recently, the U.S. National Toxicology Program conducted a 2-year bioassay study with rats exposed to doses of 10, 30, or 60 ppm naphthalene [8,9], showing a concentration-dependent increase in adenomas of the respiratory epithelium of the nose and neuroblastomas of the olfactory epithelium. These results in rodent studies have raised concerns about naphthalene as a potential human carcinogen [1,10].

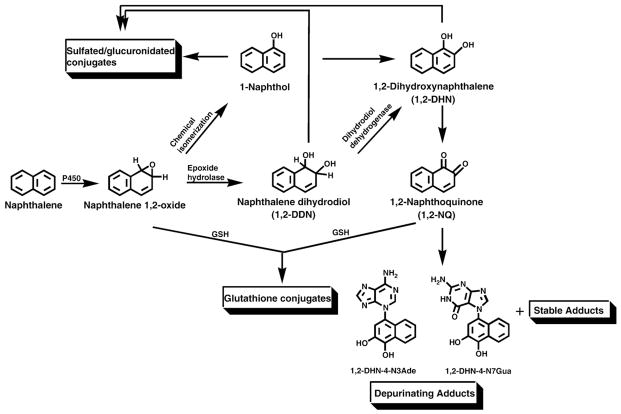

The toxicity of naphthalene depends on its metabolic activation (Fig. 1). Studies conducted in vitro and in vivo demonstrated that the first step in the metabolic conversion of naphthalene is the cytochrome P450-dependent formation of the 1,2-epoxide (Fig. 1) [5,11–16]. This compound is unstable at physiological pH [13,14] and can either react with glutathione to form glutathione conjugates or convert to the metabolites 1-naphthol by chemical isomerization or naphthalene 1,2-dihydrodiol (1,2-DDN) by epoxide hydrolase [15,16]. Conversion to 2-naphthol can occur after β-elimination of the sulfated/glucuronidated conjugate of naphthalene 1,2-dihydrodiol (not shown in Fig. 1). 1,2-DDN [17–19] or 1-naphthol [20] can be further metabolically oxidized to 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene (1,2-DHN) or its oxidized product, 1,2-naphthoquinone (1,2-NQ). 1,2-NQ is thought to be the metabolite that binds covalently to proteins [20,21]. In a recent publication, we reported the predominant formation of depurinating adducts (Fig. 1) after reaction of 1,2-NQ or enzyme-activated 1,2-DHN with DNA [22].

Fig. 1.

Pathways of naphthalene metabolism.

In this article we report our results from topical treatment of SENCAR mice with naphthalene at two dose levels. In addition, mice were treated with metabolites of naphthalene, 1-naphthol, 1,2-DDN, 1,2-DHN, and 1,2-NQ, and formation of naphthalene–DNA adducts was measured. The depurinating adducts were identified and quantified by ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) by using the standard synthesized adducts, 1,2-DHN-4-N3Ade and 1,2-DHN-4-N7Gua, whereas the unknown stable adducts were measured by the 32P-postlabeling technique. These findings are critical for understanding the metabolic activation of naphthalene in the initiation of cancer.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents, and enzymes

1,2-NQ, 1-naphthol, DMSO, boric acid, and NaBH4 were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). 1,2-DHN and 1,2-DDN were prepared by reacting 1,2-NQ with NaBH4 as described previously [23]. Proteinase K, Tris (Sigma 7–9), EDTA, 2′-deoxyguanosine 3-monophosphate (dG3p), 2′-adenosine 3-monophosphate (dA3p), 2′-cytidine 3-monophosphate (dC3p), thymidine 3-monophosphate (dT3p), NADPH, and SDS were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Histological grade acetone (Fisher Scientific) was used to prepare solutions for treatment of mouse skin.

SENCAR mouse skin treatment

Forty-nine female SENCAR mice (NCI) at 6 weeks of age were housed in the Eppley Animal Facility. When the mice were 8 weeks old, a dorsal area of the skin was shaved and groups of 4 or 5 mice were treated with the compounds. Two groups were treated with each compound and dose. Naphthalene (1200 or 500 nmol) or its metabolite (500 nmol) was dissolved in acetone to deliver a 50-μl application on the mouse skin. The treated areas were outlined immediately after the application. Four hours later, the mice were euthanized according to IACUC guidelines, and the treated areas of the skins were excised, placed together for each treatment group in 50-ml tubes, and stored at −20°C. For each set of skins, the epidermis of the mouse skin was isolated, minced, and ground together in liquid N2. Approximately 10% of the ground epidermis was used for analyzing chromosome-bound stable DNA adducts by the 32P-postlabeling technique, as described below. The remaining epidermis was processed for analyzing depurinating adducts, as described in the following section.

Sample preparation for analysis of depurinating adducts

Samples of ground epidermis were weighed and suspended in 15 ml of Tris buffer composed of 20 ml of 1 M Tris (pH 8.0), 20 ml of 0.5 M EDTA, and 1 ml of 10% SDS plus distilled water to a total volume of 100 ml. The suspension was homogenized by using a Tissue Tearor (Model 587370, BioSpec Product, Bartlesville, OK). The homogenate was incubated with proteinase K (10 mg dissolved in 1 ml of 1 M Tris, pH 8.0) at 37°C for 5 h. The resulting viscous liquid was cooled on ice, extracted with hexane to remove fat, and finally treated with 2 vol of ethanol. The precipitated material was removed by centrifuging at high speed for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed and evaporated in a Jouan RC1010 centrifuge evaporator (Jouan Inc.). The residue was suspended in 1 ml of CH3OH/H2O (1/1), filtered through a 0.2-μm acrodisc syringe filter (Fisher Scientific) directly into a 2-ml Eppendorf tube, and evaporated to about 200 μl. The solution was diluted with 1 ml of distilled water and passed through a Certify II solid phase extraction cartridge (200 mg, Varian Inc, Palo Alto, CA), which had been preequilibrated by passing successively 1 ml each of CH3OH, H2O, and 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) through it. The cartridge was then washed with 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and eluted with 1 ml of elution buffer composed of CH3OH/CH3CN/H2O/trifluoroacetic acid (8/1/1/0.1). The eluate was evaporated to dryness, dissolved in 150 μl of CH3OH/H2O (1/1), and analyzed by UPLC-MS/MS, as described below.

Ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)

Duplicate samples for each treatment group were analyzed by using a Waters Acquity Ultra Performance LC equipped with a MicroMass QuattroMicro triple stage quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA). The 10-μl injections were carried out on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEHC18 column (1.7 μm, 1×100 mm). The instrument was operated in an electrospray–positive ionization mode. All aspects of system operation, data acquisition, and processing were controlled using QuanLynx v4.0 software (Waters). The column was eluted starting with 5% CH3CN in H2O (0.1% formic acid) for 1 min at a flow rate of 150 μl/min and then changed linearly up to 55% CH3CN in 10 min. Ionization was achieved using the following settings: capillary voltage 3 kV; cone voltage 15–40 V; source block temperature 100°C; desolvation temperature 200°C with a nitrogen flow of 400 L/h. Nitrogen was used as both the desolvation and the auxiliary gas. MS/MS conditions were optimized prior to analysis using pure standards of 1,2-DHN-4-N3Ade and 1,2-DHN-4-N7Gua. Argon was used as the collision gas. Three-point calibration curves covering the range of experimental values were run for each standard; R values close to 1.00 were obtained.

Reaction of 2′-deoxyribonucleoside-3-monophosphates with 1,2-NQ or cytochrome P450-activated naphthalene

To a final 1 ml volume composed of a 3 mM solution of each of the four nucleoside 3-monophosphates (dN3p=dAp, dGp, dTp, dCp) in 0.067 M Na-K phosphate, pH 7.0, was added 0.87 mM 1,2-NQ in 20 μl of DMSO. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 h and then quenched by removal of unreacted 1,2-NQ with chloroform extractions. The aqueous layer was evaporated and the residue was suspended in 25 μl of 0.5 M Tris buffer, pH 7, and then was 32P-postlabeled as described previously [24]. For the reaction of dN3p with in situ-formed naphthalene-1,2-oxide, the mixture comprised of 0.87 mM naphthalene, 250 units of cytochrome P450 1A1, 0.6 mM NADPH, and 3 mM each of the four dN3p was incubated at 37 °C for 10 h and processed as described previously. The postlabeled adducts were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) [25], as described below.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of 32P-postlabeled adducts

The DNA digestion and 32P-postlabeling were accomplished by following the reported method [24]. Duplicate labeled samples were electrophoresed by following the method reported by Terashima [25], with a slight modification. A nondenaturing 30% polyacrylamide gel (35×42×0.04 cm) was prepared by mixing 60 ml of 40% poly-acrylamide solution, 10 ml of 10X TBE buffer, pH 7.0, 10 ml distilled water, 100 μl of 25% ammonium persulfate, and 50 μl of TEMED. The running buffer (1X TBE) was prepared from 10X stock TBE, and Na-pyrophosphate (1 mM final concentration) was added. A 10X TBE stock solution was prepared as reported previously [25]. The position of labeled adducts was established by developing an X-ray μlm exposed to the gel, which was later scanned to obtain a digital image. To measure the radioactivity of 32P-labeled products, developed photographic film was superimposed on the gel and areas showing the bands were marked on the gel. Each marked area on the gel was cut out and placed in a scintillation vial and radioactivity (cpm) was counted in a liquid scintillation counter with EcoLume fluor (ICN, Irvine, CA).

Results

Eight-week-old SENCAR mice were treated in duplicate groups on the dorsal skin with naphthalene or one of its metabolites, 1-naphthol, 1,2-DDN, 1,2-DHN, or 1,2-NQ (Fig. 1). After 4 h, the mice were sacrificed, and the skin was removed and processed for analysis of DNA adducts. The raw data obtained from UPLC-MS/MS were normalized with respect to the total weight of skin used for analysis, and the reported value of 8.5 μg of DNA per gram of skin [26] was used to calculate the results per mole DNA-P.

Depurinating adducts

Treatment of the skin with 500 nmol of naphthalene, dissolved in acetone, resulted in the formation of 0.87 pmol of the depurinating adduct 1,2-DHN-4-N3Ade/g epidermis or 0.1 μmol/mol DNA-P, when normalized with the DNA-P present in the sample (Table 1). Formation of the corresponding N7Gua adduct was not observed at this dose. By increasing the treatment dose to 1200 nmol, the amount of the N3Ade adduct observed was 2.57 pmol/g epidermis (0.3 μmol/mol DNA-P) (Fig. 2, Table 1) and, interestingly, the N7Gua adduct was also observed and quantified at 2.06 pmol/g epidermis (0.2 μmol/mol DNA-P). It is quite possible that the N7Gua adduct was formed in the low dose treatment; however, its amount was under the limit of detection.

Table 1.

Formation of depurinating and stable adducts in the mouse skin after treatment with naphthalene or its metabolites

| Treatments | Depurinating adductsa

|

Stable adductsa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmol/mol DNA-P

|

μmol/mol DNA-P

|

||||

| 1,2-DHN-4-N3Ade | 1,2-DHN-4-N7Gua | Total | With spot a | Without spot a | |

| Naphthalene | |||||

| Low dose (500 nmol) | 0.1 | NDb | 0.1 | 0.99 | 0.18 |

| High dose (1200 nmol) | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.20 |

| Naphthalene metabolites | |||||

| 1-Naphthol (500 nmol) | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.10 |

| 1,2-DDN (500 nmol) | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 0.14 |

| 1,2-DHN (500 nmol) | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.02 |

| 1,2-NQ (500 nmol) | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 1.09 | 0.23 |

Values are the average of two determinations that differed by <20%.

Not detected.

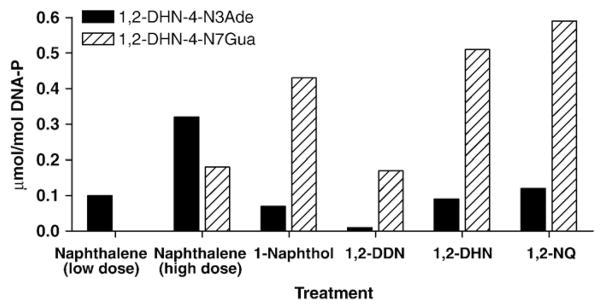

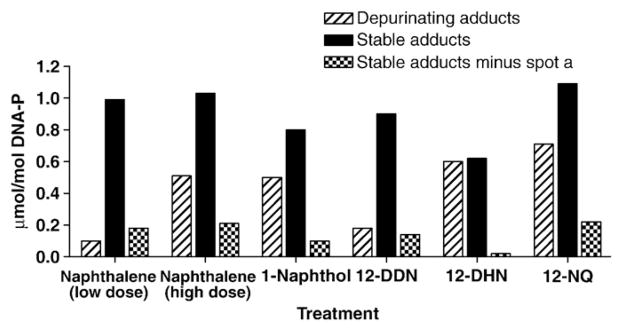

Fig. 2.

Formation of depurinating adducts in mouse skin treated with naphthalene or one of its metabolites. The values are the average of two determinations that differed by <20%.

Formation of both depurinating adducts, 1,2-DHN-4-N3Ade and 1,2-DHN-4-N7Gua, was also observed by treating the mouse skin with metabolites of naphthalene, namely 1-naphthol, 1,2-DDN, 1,2-DHN, and 1,2-NQ. Treatment with the ortho-quinone, 1,2-NQ, produced the depurinating 1,2-DHN-4-N7Gua adduct in almost fivefold higher amounts than that of the corresponding N3Ade adduct (Fig. 2, Table 1). An approximately similar result was obtained when the mouse skin was treated with the catechol metabolite, 1,2-DHN; however, the overall level of the depurinating adducts was slightly lower than that obtained with the quinone metabolite. Treatment with 1,2-DDN produced much lower amounts of the depurinating adducts compared to those obtained with 1-naphthol,1,2-DHN, or 1,2-NQ (Fig. 2, Table 1). This can be tentatively explained by the absence of the enzyme dihydrodiol dehydrogenase in mouse skin (Fig. 1). In that case, 1,2-DDN would conjugate with sulfate or glucuronide and be converted to 2-naphthol by β-elimination (not shown in Fig. 1) [17–19]. The 2-naphthol can be metabolically oxidized to 1,2-DHN and then further oxidized to 1,2-NQ.

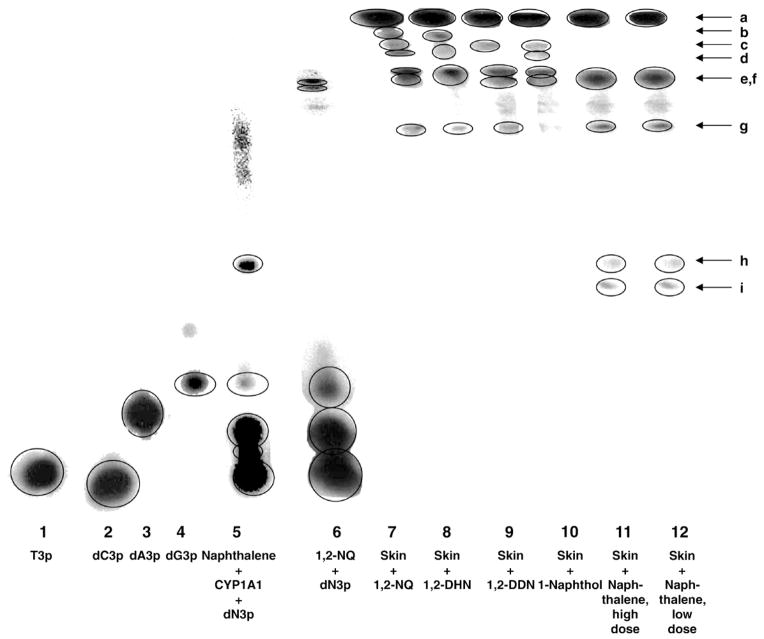

Stable adducts

Formation of stable adducts was measured by using a recently reported method, under slightly modified conditions, to resolve the 32P-postlabeled adducts by electrophoresis on polyacrylamide gel [25]. Samples 1–4 in Fig. 3 show the standard nucleoside-3-monophosphates after postlabeling. To address the qualitative nature of the bands obtained after treatment of skin with naphthalene or its metabolites, we performed a standard reaction in which a mixture of nucleoside-3-monophosphates reacted with 1,2-NQ (sample 6) or naphthalene 1,2-oxide, produced in situ by incubating naphthalene with cytochrome P450 1A1 [27] (lane 5). Under similar conditions of 32P-postlabeling, a number of bands (a–i) were observed for different mouse skin treatments (samples 7–12). Bands a and g were present in all of the treatments, whereas other spots were seen with various treatments. Most importantly, bands h and i were present only following treatment with naphthalene, and they corresponded to the bands obtained from naphthalene 1,2-oxide (lanes 5, 11, and 12).

Fig. 3.

PAGE analysis of 32P-postlabeled stable DNA adducts obtained from naphthalene and its metabolites in vitro and in vivo. For the in vivo study, naphthalene (1200 or 500 nmol) or its metabolite (500 nmol) was delivered in 50 μl acetone to mouse skin.

The level of formation of stable adducts was found to be in the range of 0.99–1.09 μmol/mol DNA-P. A dose-dependent increase in formation of stable adducts was not observed when the dose of naphthalene was changed from 500 to 1200 nmol, as shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1. In treatments with the metabolites, the highest level of adducts was seen with 1,2-NQ (Fig. 4) and, unexpectedly, 1,2-DHN made relatively lower amounts of stable adducts. The overall trend of formation of stable adducts with metabolites was found in the order: 1,2-NQ >1,2-DDN >1-naphthol >1,2-DHN.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative comparison of depurinating and stable adducts formed in mouse skin treated with naphthalene (500 or 1200 nmol) or one of its metabolites (500 nmol). The values are an average of two determinations that differed by <20%.

Discussion

Naphthalene is the most abundant member of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are produced primarily from incomplete combustion of hydrocarbon fuels. Although hydrocarbons with the greatest carcinogenic potency tend to have four to seven condensed aromatic rings, naphthalene, with two rings, has produced respiratory tract tumors in rats and mice of both sexes [1,7–10]. The apparent carcinogenicity of naphthalene in two mammalian species, coupled with the abundance of naphthalene in indoor and outdoor air, motivated the International Agency for Research on Cancer [1] and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [4] to reclassify naphthalene as a possible human carcinogen.

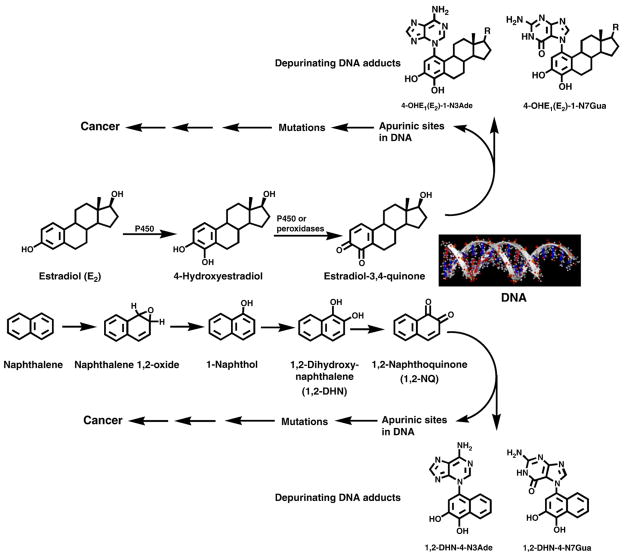

The mechanism of cancer initiation by naphthalene cannot be explained by either of the two major mechanisms of activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In fact, carcinogenic activation of naphthalene cannot occur by formation of diol epoxides [28] because it lacks a bay region or by radical cations because its ionization potential is too high [28]. It can be metabolized, however, to the electrophilic 1,2-NQ, which has the potential to react with DNA. Our previous studies on natural estrogens [29–32], synthetic estrogens [32–34], benzene [35], and dopamine [35] demonstrate the involvement of electrophilic ortho-quinones in the predominant formation of depurinating adducts. Therefore, we propose, analogously to the natural estrogens, the metabolic activation of naphthalene to ultimate carcinogenic 1,2-NQ, which reacts with DNA to form adducts (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparable mechanisms of cancer initiation by natural estrogens and naphthalene.

The major initiating pathway for estradiol (E2) is illustrated in Fig. 5. E2 can be metabolically converted to 4-hydroxy E2 (4-OHE2) by cytochrome P450. Oxidation of this catechol estrogen leads to the corresponding E2-3,4-quinone, which can react with DNA to form a small amount of stable adducts and predominant amounts of depurinating adducts, 4-OHE2-1-N3Ade and 4-OHE2-1-N7Gua (Fig. 5) [29–31]. These adducts detach from DNA, leaving behind apurinic sites, which can generate the critical mutations that initiate cancer [36–39]. Analogously, the conversion of naphthalene to 1-naphthol and further metabolic oxidation to 1,2-DHN and then to 1,2-NQ can lead to reaction of the latter with DNA and generation of stable adducts and depurinating 1,2-DHN-4-N3Ade and 1,2-DHN-4-N7Gua adducts (Fig. 5). As discussed below, we think the apurinic sites formed by loss of the depurinating adducts play a major role in the initiation of cancer by naphthalene.

Depurinating adducts

The depurinating and stable adducts formed in mouse skin after treatment with naphthalene at two dose levels or with naphthalene metabolites produced fairly similar results, as shown in Fig. 4. For the depurinating adducts (Fig. 2), the N3Ade adducts are more abundant than the N7Gua adducts when the skin is treated with naphthalene. Following treatment with the metabolites, the N7Gua adducts are the more abundant ones. Since the depurinating adducts were analyzed after a 4-h treatment of the skin and the conversion of naphthalene to 1,2-NQ required 3 metabolic steps, we speculate that the N3Ade adducts predominate because they are released from DNA instantaneously. In contrast, when the skins were treated with the metabolites, the conversion to 1,2-NQ required at most two steps. In this case it can be assumed that the instantaneously released N3Ade adducts have the time to diffuse out of the tissue, while the slowly released N7Gua adducts are still accumulated in the skin. This has been previously observed with depurinating polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon adducts in mouse skin [40].

Stable adducts

A variety of stable adducts were detected when mouse skin was treated with naphthalene or one of its metabolites (Fig. 3). When enzyme-activated naphthalene was reacted with a mixture of the four deoxyribonucleoside monophosphates (lane 5), one major adduct spot was observed (spot h + i). In contrast, when 1,2-NQ was reacted with the dN3ps (lane 6), the major spots were e and f. Adduct spots h and i were also observed when mouse skin was treated with naphthalene (lanes 11 and 12). These results suggest that the adducts in spots h and i arise from the naphthalene 1,2-oxide metabolite.

By far the major adduct spot observed in mouse skin preparations is spot a (lanes 7–12). Because this spot was never observed with the dN3ps (lanes 1–6), we think it is an artifact spot containing partially digested DNA. Therefore, we have calculated the total stable adducts both with and without spot a (Fig. 4, Table 1). When spot a is removed from consideration, the major adducts observed in the skin are e and f, which arise from reaction of 1,2-NQ with the DNA (lanes 6–12).

In addition, the depurinating adducts become the predominant ones with naphthalene and its metabolites, except at the low dose of naphthalene. Although formation of depurinating naphthalene–DNA adducts appears to predominate, the proportion of stable naphthalene–DNA adducts is higher than with the other carcinogens activated through formation of an ortho-quinone, which typically generates ca 1% stable adducts [29–35]. The abasic sites formed by loss of the depurinating adducts can generate mutations that may lead to the initiation of cancer.

Conclusions

1,2-NQ and enzymically activated naphthalene, 1-naphthol, 1,2-DDN, and 1,2-DHN react with DNA by 1,4-Michael addition to form specifically the depurinating 1,2-DHN-1-N3Ade and 1,2-DHN-1-N7Gua adducts. The 1,2-NQ also forms the major stable adducts (if spot a is not considered in Fig. 3). These chemical and biochemical properties are similar to those of the catechol-3,4-quinones of the natural estrogens [29–31], the catechol quinones of the synthetic estrogens diethylstilbestrol [34], and its hydrogenated derivative hexestrol [32,33], the catechol quinone of the leukemogen benzene [35], and the neurotransmitter dopamine [35]. The apurinic sites formed by the depurinating DNA adducts may be converted by error-prone base-excision repair into mutations that can initiate cancer [36–39,41]. Therefore, the formation of catechol quinones that can react by 1,4-Michael addition with DNA to form the depurinating N3Ade and N7Gua adducts constitutes the mechanism of cancer initiation for weak carcinogens.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant P01 CA49210. Core support at the Eppley Institute was provided by Grant P30 CA36727 from the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- Ade

adenine

- 1,2-DDN

1,2-dihydro-1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene

- 1,2-DHN

1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene

- dN3p

2′-deoxynucleoside 3-monophosphate

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid disodium salt

- Gua

guanine

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- 1,2-NQ

1,2-naphthoquinon

- 4-OHE2

4-hydroxyestradiol

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TBE

Tris-boric acid-EDTA buffer

- TEMED

N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine

- UPLC-MS/MS

ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

References

- 1.IARC. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: some traditional herbal medicines, some mycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. Vol. 82. France, Lyon: 2002. pp. 367–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley JS. Environmental Protection Agency, office of toxic substances. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: 1986. Broad scan analysis of the FY82 national human adipose tissue survey specimens, executive summary (EPA-560/5-86-035) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellizzari ED, Hartwell TD, Harris BSH, III, Waddell RD, Whitaker DA, Erickson MD. Purgeable organic compounds in mother’s milk. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1982;28:322–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01608515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Environmental Protection Agency. Clean air act amendments of 1990 conference report to accompany S. 1630. Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics; Washington, DC: 1990. (Report No. 101–952) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckpitt A, Boland B, Isbell M, Morin D, Shultz M, Baldwin R, Chan K, Karlsson A, Lin C, Taff A, West J, Fanucchi M, Van Winkle L, Plopper C. Naphthalene-induced respiratory tract toxicity: metabolic mechanisms of toxicity. Drug Metab Rev. 2002;34:791–820. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120015694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Toxicology Program (NTP) Technical Report Series No. 410, NIH Publication No. 92–3141. Research Triangle Park, NC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 1992. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of naphthalene (CAS No. 91-20-3) in B6C3F1 mice (inhalation studies) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdo KM, Eustis SL, McDonald M, Joiken MP, Adkins B, Haseman JK. Naphthalene: a respiratory tract toxicant and carcinogen for mice. Inhal Toxicol. 1992;4:393–409. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdo KM, Grumbein S, Chou BJ, Herbert R. Toxicity and carcinogenicity study in F344 rats following 2 years of whole-body exposure to naphthalene vapors. Inhal Toxicol. 2001;13:931–950. doi: 10.1080/089583701752378179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Toxicology Program (NTP) CNTP Technical Report Series No. 500; NIH publication No. 01–4434. Research Triangle Park, NC: 2000. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of naphthalene (CAS No. 91-20-3) in F344/N rats (inhalation studies) [Google Scholar]

- 10.North DW, Abdo KM, Benson JM, Dahl AR, Morris JB, Renne R, Witschi H. A review of whole animal bioassays of the carcinogenic potential of naphthalene. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;51:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckpitt AR, Castagnoli N, Nelson SD, Jones AD, Bahnson LS. Stereoselectivity of naphthalene epoxidation by mouse, rat and hamster pulmonary, hepatic and renal microsomal enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1987;15:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jerina DM, Daly JW, Witkop B, Zaltzman-Nirenberg Z, Udenfriend S. 1,2-Naphthalene oxide as an intermediate in the microsomal hydroxylation of naphthalene. Biochemistry. 1970;9:147–156. doi: 10.1021/bi00803a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Bladeren PJ, Vyas KP, Sayer JM, Ryan DE, Thomas PE, Levin W, Jerina DM. Stereoselectivity of cytochrome P-450c in the formation of naphthalene and anthracene 1,2-oxides. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8966–8973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanekal S, Plopper C, Morin D, Buckpitt A. Metabolism and cytotoxicity of naphthalene oxide in the isolated perfused mouse lung. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;256:391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckpitt AR, Bahnson LS. Naphthalene metabolism by human lung microsomal enzymes. Toxicology. 1986;41:333–341. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(86)90186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tingle MD, Pirmohamed M, Templeton E, Wilson AS, Madden S, Kitteringham NR, Park BK. An investigation of the formation of cytotoxic, genotoxic, protein-reactive and stable metabolites from naphthalene by human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:1529–1538. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90319-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smithgall TE, Harvey RG, Penning TM. Spectroscopic identification of ortho-quinones as the products of polycyclic aromatic trans-dihydrodiol oxidation catalyzed by dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:1814–1820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turkall RM, Skowronski GA, Kadry AM, Abdel-Rahman MS. A comparative study of the kinetics and bioavailability of pure and soil-absorbed naphthalene in dermally exposed male rats. Arch Environ Toxicol. 1994;26:504–509. doi: 10.1007/BF00214154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakke J, Struble C, Gustafsson J-Å, Gustafsson B. Catabolism of premercapturic acid pathway metabolites of naphthalene to naphthols and methylthio-containing metabolites in rats. Biochemistry. 1985;82:668–671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.d’Arcy Doherty M, Makowski R, Gibson GG, Cohen GM. Cytochrome P-450 dependent metabolic activation of 1-naphthol to naphthoquinones and covalent binding species. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34:2261–2267. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flueraru M, Chichirau A, Chepelev LL, Willmore WG, Durst T, Charron M, Barclay LR, Wright JS. Cytotoxicity and cytoprotective activity in naphthale-nediols depends on their tendency to form naphthoquinones. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1368–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeed M, Higginbotham S, Rogan E, Cavalieri E. Formation of depurinating N3adenine and N7guanine adducts after reaction of 1,2-naphthoquinone or enzyme-activated 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene with DNA. Implications for the mechanism of tumor initiation by naphthalene. Chem-Biol Interact. 2007;165:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platt KL, Oesch F. Efficient synthesis of non-K-region trans-dihydro diols of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from o-quinones and catechols. J Org Chem. 1983;48:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodell WJ, Devanesan PD, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL. 32P-Postlabeling analysis of benzo [a]pyrene-DNA adducts formed in vitro and in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 1989;2:312–315. doi: 10.1021/tx00011a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terashima I, Suzuki N, Shibutani S. 32P-Postlabeling/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis: application to the detection of DNA adducts. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:305–311. doi: 10.1021/tx010083c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devanesan PD, RamaKrishna NVS, Padmavathi NS, Higginbotham S, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL, Marsch GA, Jankowiak R, Small JG. Identification and quantitation of 7,12-dimethylbenz [a]anthracene-DNA adducts formed in mouse skin. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:364–371. doi: 10.1021/tx00033a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu R, Waidyanatha S, Henderson AP, Serdar B, Zheng Y, Rappaport SM. Determination of dihydroxynaphthalenes in human urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2005;826:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalieri E, Rogan E. Mechanisms of tumor initiation by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mammals. In: Neilson AH, editor. The handbook of environmental chemistry. PAHs and related compounds. 3J. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 1998. pp. 81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavalieri EL, Stack DE, Devanesan PD, Todorovic R, Dwivedy I, Higginbotham S, Johansson SL, Patil KD, Gross ML, Gooden JK, Ramanathan R, Cerny RL, Rogan EG. Molecular origin of cancer: catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones as endogenous tumor initiators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10937–10942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li KM, Todorovic R, Devanesan P, Higginbotham S, Kofeler H, Ramanathan R, Gross ML, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL. Metabolism and DNA binding studies of 4-hydroxyestradiol and estradiol-3,4-quinone in vitro and in female ACI rat mammary gland in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:289–297. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahid M, Kohli E, Saeed M, Rogan E, Cavalieri E. The greater reactivity of estradiol-3,4-quinone vs estradiol-2,3-quinone with DNA in the formation of depurinating adducts: implications for tumor-initiating activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:164–172. doi: 10.1021/tx050229y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeed M, Zahid M, Gunselman SJ, Rogan E, Cavalieri E. Slow loss of deoxyribose from the N7deoxyguanosine adducts of estradiol-3,4-quinone and hexestrol-3′,4′-quinone. Implications for mutagenic activity. Steroids. 2005;70:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saeed M, Gunselman SJ, Higginbotham S, Rogan E, Cavalieri E. Formation of the depurinating N3Adenine and N7Guanine adducts by reaction of DNA with hexestrol-3′,4′-quinone or enzyme activated 3′-hydroxyhexestrol. Implications for a unifying mechanism of tumor initiation by natural and synthetic estrogens. Steroids. 2005;70:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saeed M, Rogan E, Cavalieri E. Mechanism of metabolic activation and DNA adduct formation by the human carcinogen diethylstilbestrol: the defining link to natural estrogens. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1276–1284. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavalieri EL, Li K-M, Balu N, Saeed M, Devanesan P, Higginbotham S, Zhao J, Gross ML, Rogan E. Catechol ortho-quinones: the electrophilic compounds that form depurinating DNA adducts and could initiate cancer and other diseases. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1071–1077. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavalieri E, Rogan E. Catechol quinones of estrogen in the initiation of breast, prostate, and other human cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:286–301. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarti D, Mailander P, Li K-M, Higginbotham S, Zhang H, Gross ML, Cavalieri E, Rogan E. Evidence that a burst of DNA depurination in SENCAR mouse skin induces error-prone repair and forms mutations in the H-ras gene. Oncogene. 2001;20:7945–7953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mailander PC, Meza JL, Higginbotham S, Chakravarti D. Induction of A.T to G.C mutations by erroneous repair of depurinated DNA following estrogen treatment of the mammary gland of ACI rats. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;101:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Z, Kosinska W, Khmelnitsky M, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, Chakravarti D, Sacks P, Guttenplan JB. Mutagenic activity of 4-hydroxyestradiol, but not 2-hydroxyestradiol, in BB2 rat embryonic cells, and the mutational spectrum of 4-hydoxyestradiol. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:475–479. doi: 10.1021/tx0502645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogan EG, Devanesan PD, RamaKrishna NVS, Higginbotham S, Padmavathi NS, Chapman K, Cavalieri EL, Jeong H, Jankowiak R, Small GJ. Identification and quantitation of benzo [a]pyrene-DNA adducts formed in mouse skin. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:356–363. doi: 10.1021/tx00033a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakravarti D, Mailander PC, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Evidence that error-prone DNA repair converts dibenzo [a,l]pyrene-induced depurinating lesions into mutations: formation, clonal proliferation and regression of initiated cells carrying H-ras oncogene mutations in early preneoplasia. Mutat Res. 2000;456:17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]