Abstract

Hózhó is the complex wellness philosophy and belief system of the Diné (Navajo) people, comprised of principles that guide one's thoughts, actions, behaviors, and speech. The alignment of integrative nursing principles and the Hózhó Wellness Philosophy illustrates the power that integrative nursing offers as a meta-theoretical perspective that can transform our healthcare system so that it is inclusive and responsive to the needs of our varied populations. Integrative nursing offers the opportunity to re-introduce cultural wellness wisdom, such as Hózhó, as a means to improve whole-person/whole-systems wellbeing and resilience. Integrative nursing, through the acceptance and validation of indigenous health-sustaining wisdom, contributes to the delivery of effective, authentic, culturally tailored, whole-person/whole-system, patient-centered, relationship-based healthcare. Highlighting the Diné Hózhó philosophy re-introduces this philosophy to the Diné, other American Indian/Alaska Native nations, global indigenous cultures, and even nonindigenous people of the world as a means to promote and sustain global health and wellbeing.

Key Words: Integrative Nursing, American Indian, culture, Hózhó, wellness, wellness philosophy

摘要

美是一种复杂的健康理念和纳瓦 霍人的信仰体系,由人的思想、 行动、行为和言论组成。 综合 护理原则与美的健康理念整合, 说明综合护理提供了一种荟萃理论观点,能转换我们的医疗体 系,令其包容并对不同人群的需 求做出响应。 综合护理提供了 重新引入文化中的健康智慧(如 美)的机会,以作为一种改善全 人/全体系的健康和适应力的手 段。 综合护理通过接受和验证 土著健康维持智慧,从而有助于 提供有效、真实、文化量身定 制、全人/全体系、以患者为中心的、以关系为基础的医疗护 理。 突出纳瓦霍的美的理念, 将 这 一 理 念 重 新 引 入 了 纳 瓦 霍 人、其他美国印第安人/阿拉斯 加 原 住 民 国 家 、 全 球 的 土 著 文 化、甚至全球的原住民的生活, 作为一种促进和维持全球健康和 福祉的手段。

SINOPSIS

Hózhó es el complejo sistema de creencias y la filosofía del bienestar de los Diné (Navajos) que abarca los principios que guían los pensamientos, acciones, comportamientos y el habla de una persona. La convergencia de los principios de la atención integral con la filosofía Hózhó del bienestar ilustra el poder que la atención integral ofrece como perspectiva metateórica que puede transformar nuestro sistema sanitario, de forma que sea inclusivo y dé respuesta a las necesidades de nuestra variada población. La atención integral ofrece la oportunidad de volver a introducir el bagaje cultural relativo al bienestar, como el Hózhó, como un medio para mejorar el bienestar y la recuperación tanto en las personas como en los sistemas. La atención integral, a través de la aceptación y validación de la sabiduría indígena relacionada con la salud, contribuye a proporcionar una asistencia sanitaria efectiva, auténtica, adaptada culturalmente, individual, integral, centrada en el paciente y basada en los vínculos. Destacar la filosofía Hózhó de los Diné hace que esta filosofía vuelva a introducir a los Diné, a otras naciones nativas de indios americanos y de Alaska, a las culturas indígenas globales e incluso a las personas no indígenas del mundo como un medio para promover y mantener la salud y el bienestar global.

Hózhó is a complex wellness philosophy and belief system comprised of principles that guide one's thoughts, actions, behaviors, and speech. The teachings of Hózhó are imbedded in the Hózhóójí Nanitiin (Diné traditional teachings) given to the Diné by the holy female deity Yoołgaii Asdzáá (White Shell Woman)1-3 and the Diné holy people (sacred spiritual Navajo deities). Hózhó philosophy emphasizes that humans have the ability to be self-empowered through responsible thought, speech, and behavior. Likewise, Hózhó acknowledges that humans can self-destruct by thinking, speaking, and behaving irresponsibly. As such, the Hózhó philosophy offers key elements of the moral and behavioral conduct necessary for a long healthy life, placing an emphasis on the importance of maintaining relationships by “developing pride of one's body, mind, soul, spirit and honoring all life.”1

Hózhó is difficult to convey as it encompasses both a way of living and a state of being. Wyman and Haile describe Hózhó as “everything that a Navajo thinks as good—that is good as opposed to evil, favorable to man as opposed to unfavorable or doubtful.”4 It expresses for the Navajo such concepts as the words beauty, perfection, harmony, goodness, normality, success, wellbeing, blessedness, order, and ideal.4 Witherspoon also describes Hózhó as “everything that is positive, and it refers to an environment which is all inclusive.”5 Hózhó reflects the process, the path, or journey by which an individual strives toward and attains this state of wellness. Thus, translating the complex meaning of Hózhó without reducing its expansive meaning is difficult.

Our efforts to definitively or operationally describe Hózhó for both researchers and clinicians are a humble attempt to capture the essence of this wellness philosophy held sacred by the Diné and is not meant to disrespect or reduce the meaning of this sacred Diné philosophy. Therefore, our goal of explicating the essence of Hózhó is intended to revive, share, and preserve the health-sustaining wisdom of this ancient wellness philosophy for present and future generations of Diné and so that others might learn from this ancient philosophy.

Hózhó may be best understood by describing characteristics of a Diné individual who excels in his or her journey to achieve this revered state of being. Diné elders are the ideal role models; Diné elders have both received the ancient teachings of Hózhó and have had a lifetime of experience in working toward attaining Hózhó. People living consistently with Hózhó ideas are humble; intelligent; patient; respectful and thoughtful (demonstrated in speech, actions, relationships); soft spoken; good and attentive listeners; disciplined, hardworking, physically fit, and strong; generous; supportive, caring, and empathetic; positive in thought, speech, and behaviors; spiritual; loyal and reliable; honest; creative and artistic; peaceful and harmonious; perceptive, understanding, and wise; confident; calm; deliberate in actions; gentle yet firm; and self-controlled.3,7 Hózhó teaches that respectful thought, speech, and behavior should be nurtured and relationships in life, including those with the whole of creation in the universe, should be supportive and positive.3,6,7

Recognizing that many of the characteristics that are used to teach and convey Hózhó are conceptually vague and open to multiple interpretations, a concept analysis of the Diné Hózhó Wellness Philosophy was completed to encourage the discernment required to study, test, and teach this wellness philosophy more widely. The 6 conceptually distinct attributes of Hózhó—spirituality, respect, reciprocity, discipline, thinking, and relationships—are necessary elements to whole-person and whole-systems wellbeing described as the Diné wellness ideal.8 Spirituality represents expectation to respect and honor spirit through prayer, paying homage to spirit, ritual, ceremony, and spiritual/religious practice. Respect is the act of maintaining loyal reverence by offering respect to self, others, nature, spirit, animals, the Creator, and the environment. Reciprocity represents the constant graceful and respectful exchange and receipt of support, acts of kindness, helpfulness, and tokens of appreciation or honor—nothing is ever received without giving, and the characteristic of generosity is essential for authentic reciprocity. Discipline represents the commitment to achieving life goals through sustaining disciplined productive daily activity in the form of study, self-care, physical activity, and helpfulness to others. Thinking represents the cognitive functioning required to maintain consistent positive thought while planning and organizing the present and future. The honoring of Relationships (Ké—the Diné connectedness to family, clan, tribe, community) is a central theme, requiring a constant awareness of the relationships and interconnectedness between one and the environment (others, family, community, tribe, spirits, people of the world, all living creatures, nature, and the universe).

The Holy People ordained

Through songs and prayers,

That

Earth and universe embody thinking,

Water and the sacred mountains embody planning,

Air and variegated vegetation embody life,

Fire, light, and offering sites of variegated sacred stones embody wisdom.

These are the fundamental tenets established.

Thinking is the foundation of planning.

Life is the foundation of wisdom.

Upon our creation, these were instituted within us and we embody them.

Accordingly, we are identified by:

Our Diné name,

Our clan,

Our language,

Our life way,

Our shadow,

Our footprints.

Therefore, we were called the Holy Earth-Surface-People.

From here growth began and the journey proceeds.

Different thinking, planning, life ways, languages, beliefs, and laws appear among us,

But the fundamental laws placed by the Holy People remain unchanged.

Hence, as we were created with living soul, we remain Diné forever.

—Excerpt from The Fundamental Law of the Navajo Nation (2015)9

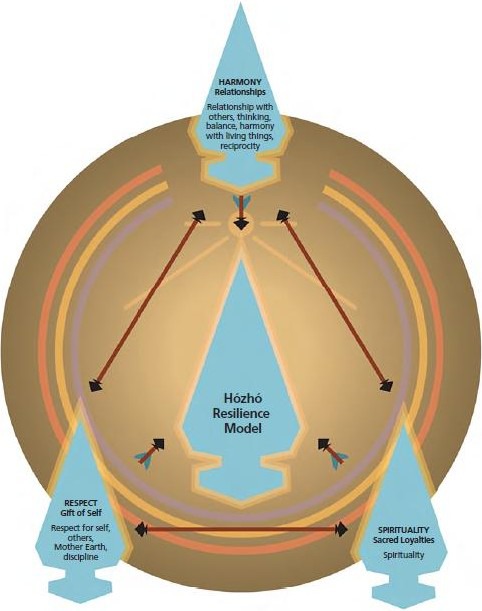

Kahn-John then further refined this Diné model of health and wellbeing by conducting a secondary analysis of pre-existing data from the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, leading to the development of the Hózhó Resilience Model (HRM; Figure).10 The HRM consists of 3 domains—harmony, respect, and spirituality—reflective of the original 6 identified attributes of the Diné Hózhó Wellness Philosophy. Interestingly, the time-honored traditions of the Diné people and their beliefs and teachings about how to live a long and healthy life through practicing Hózhó aligns with the meta-theoretical beliefs, values, and principles of integrative nursing, providing mutually beneficial validation of the value and potential validity of these two models of whole-person wellbeing and resilience. Further, the consistency that we have found between the Diné Hózhó Wellness Philosophy and integrative nursing supports Kreitzer and Koithan's claims that the practice of integrative nursing is not new; the beliefs, values, and practices have existed in cultures and in healing practices, including nursing, worldwide for hundreds of years.11

Figure.

The Hózhó Resilience Model. © Michelle Kahn-John.

THE INTERSECTION OF HóZHó WELLNESS PHILOSOPHY AND INTEGRATIVE NURSING

The 6 principles of integrative nursing are used to frame the comparison of the two perspectives on whole-person/whole-systems health and wellbeing. These principles include (1) human beings are whole systems, inseparable from their environments; (2) human beings have the innate capacity for health and wellbeing; (3) nature has healing and restorative properties that contribute to health and wellbeing; (4) integrative nursing is person-centered and relationship-based; (5) integrative nursing is informed by evidence and uses the full range of therapeutic modalities to support/augment the healing process, moving from least intensive/invasive to more, depending on need and context; and (6) integrative nursing focuses on the health and wellbeing of caregivers as well as those they serve.11,12

Human Beings Are Whole Systems, Inseparable From Their Environments

In Diné teachings, to live in a state of Hózhó requires conscious awareness of the collective and interrelated relationships between self and others. Others are broadly defined and include the universal whole: (1) the elements of nature, including animals and insects; (2) the Creator; (3) the Diné holy people; (4) spirits; (5) Mother Earth; (6) Father Sky; and (7) the distinct characteristics and cycles within nature and the universe such as seasons, night, day, sun, moon, stars, time.2,3,5,11 The conscious awareness of this inseparable interrelatedness between human beings and their environment establishes an ownership with responsibility to honor and respect each aspect of ourselves and our inseparable connections to nature and the universe.

The inseparable nature between humans and the universal whole lends to the reality of a pre-existing network of internal, external, and existential support for each human being. These relational systems (self, relatives, community, healthcare, healing systems, healers, nature and the environment, culture, and spirits) support human beings on physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and existential planes to meet our biopsychosocialspiritual needs. Recognizing the existence and availability of these supportive entities is critical to establishing and maintaining health and wellbeing.

Human Beings Have the Innate Capacity for Health and Wellbeing

Hózhó is built on positive certainties of the innate capacity of each individual to achieve wholeness, happiness, health, balance, harmony, and ultimate wellbeing through attentive conscious practice of the Hózhó attributes. The Hózhó teachings emphasize the utmost sacredness of the collective human body-mind-spirit that is naturally situated within the healing resources of the environment (eg, family, community, spirits, nature, animals). Hózhó becomes disrupted as a result of irresponsible thoughts, speech, or behavior, resulting in disharmony, or Hóchxó, which is manifested as chaos, ignorance, evil, sadness, grief, disharmony, imbalance—all that is contra to Hózhó.5,8

However, the Diné belief in the human being's innate ability and capacity to heal empowers those experiencing Hóchxó with the hope of re-establishing individual, community, and environmental health through conscious participation in the process to attain Hózhó. A Diné restorative healing ceremony based on the Hózhó teachings is the Hózhóóji (Blessing Way) Ceremony.3,7 The Hózhóóji ceremony is performed when one needs additional support from a healer, the extended family, spirits, nature, and the Diné holy people to re-establish a state of Hózhó.

Nature Has Healing and Restorative Properties That Contribute to Health and Wellbeing

Hózhó recognizes and honors the healing energy and restorative properties of nature and the universal whole. The Hózhó teachings insist on a high regard for animals, living creatures, nature, and elements of the earth because of their influence (both negative and positive) on the health and wellbeing of human beings. Recognizing that animals, all living creatures, and elements of nature (water, minerals, plants, air) serve as sources of food, shelter, spiritual guidance, and spiritual healing, the Diné people hold them as sacred.3,7

Diné and American Indian (AI) healing ceremonies incorporate elements of nature (plants, herbs, air, fire, water, earth), living animals and living creatures, and nonliving animal essence (feathers, hides, bones, and tissue) to cleanse, purify, and restore optimal body-mind-spirit wellbeing.2,3,7,13-15 Likewise, the Diné make sacred offerings to animals and nature to honor their interdependent relationship and express gratitude for their support, ensuring day-to-day opportunities for the healing exchanges and interactions.

Integrative Nursing Is Person-centered and Relationship-based

The teachings of Hózhó stress the importance of nurturing and sustaining relationship with self and others through respectful thought, speech, and behavior.14 Relationship with self is viewed as most critical, requiring full understanding of the sacred nature of the collective body-mind-spirit. When the sacred miracle of self is fully embraced, the person operates from a grounded, person-centered perspective and is prepared to extend the honor to external relationships that are not limited to other human beings; the Diné often extend relationships to animals, spirits, and elements of nature. Constant practice of respect for self and others helps a person master the teachings of Hózhó and an awareness of the differences between positive, nurturing relationships and negative, destructive relationships. Recognizing the sacredness of self enables recognition of the sacredness of others, thus establishing the essential, interdependent, dynamic nature of relationships that are viewed as sources of stability and support. AI cultural teachings imply that relationships are everlasting, undergoing only temporary disruptions at times of separation, death, or physical absence.3 When a relationship becomes disrupted, the disruption impacts the collective unified whole, including friends and distant relatives, pets and animals, the collective environment, and perhaps even spiritual ancestors and future generations.

Hózhó teachings remind us of the often forgotten relationships between living beings, elements of nature, and inanimate objects, such as the relationship one has with his or her home or with sacred items such as protective stones and arrowheads. The Diné honor their relationship with the home by blessing and showing gratitude for the home. Recognizing the sacred protective and sheltering properties of homes, the Diné bestow honor and respect on the home through song and action. Homes are often adorned with objects that protect the home and the people, animals, inanimate objects, and spirits within.3

The effort of maintaining relationships is constant, a grounding force that promotes individual, spiritual, and collective health and strength. Generosity and reciprocity are significant in Hózhó philosophy and precious gem (white shell, turquoise, abalone, and jet) and corn offerings are symbolic of the honored relationships between humans and Mother Earth, Father Sky, lightning, the sun, the moon, the Creator, and The Holy People.3,16 Likewise, reciprocal exchanges of support, food, gifts, love, compassion, and respect are viewed as a means of maintaining relationship. Honoring, preserving, sustaining, and nurturing positive and healthy interdependent relationships may be the richest source of internal, external, and existential health protection attained through the practice of Diné Hózhó.

Integrative Nursing Is Informed by Evidence

Integrative nursing is informed by evidence and uses the full range of therapeutic modalities to support/augment the healing process, moving from least intensive/invasive to more, depending on need and context. Hózhó wellness philosophy is inclusive of all that contributes to wellbeing. The survival and transfer of the Hózhó philosophy across generations of Diné serve as evidence of the value and significance of these teachings for the health and wellbeing of the Diné. Because Hózhó philosophy embraces all mechanisms that lead to wellbeing, the full range of therapeutic healing modalities (eg, Western medicine, AI medicine, AI spiritual healing, AI healing ceremonies, complementary and alternative health options) that support the attainment of physical, mental, spiritual, emotional, social, and environmental wellbeing align with the goal of Hózhó. There remains limited Western scientific evidence to confirm the health protective benefits of AI cultural wisdom; however, emerging scientific literature does support and recognize the validity of indigenous ways of knowing as a source of rigorous and relevant knowledge relevant for the improved health of indigenous people.17 The ways in which American Indians and indigenous people view and approach knowledge differ from the ways in which Western scientific, evidence-based knowledge is viewed and approached.18 Indigenous knowledge is shared, transmitted orally, role-modeled, and often received interpersonally or through spiritual processes, ceremony, interpretation of symbols and divination, and through dreams and visions. Indigenous knowledge is local, culturally specific, and unique to a certain population.17 Indigenous knowledge in the form of culture, stories, chants, song, and prayer is also thought to be alive, and the sharing of this knowledge requires levels of care and respect in the exploration and transmission of the knowledge.3,17

Harvey emphasizes the need for a constructive synthesis of differing worldviews, ideologies, and technologies through the application of indigenous wisdom as a means to improve the health of indigenous populations.19 The evidence supporting Hózhó as a health-sustaining philosophy is apparent in the survival of the Diné as well as in the survival of the oral teachings and patterned behaviors of the Diné. These patterns of Diné thought, speech, and behavior have endured for generations, despite the historical traumatic events of the past.20,21 Yet to improve the health of the Diné, the tenets of Hózhó philosophy must be explored, understood, correctly translated, and conveyed to the people using methods such as storytelling, talking circles, or broadcasting via older (radio) and contemporary (social networking) media—communicating the significant benefits of the ancient, time-honored Hózhó wisdom to all generations of Diné as well as all individuals interested in sharing in this valuable health-sustaining knowledge.

Integrative Nursing Focuses on the Health and Wellbeing of Caregivers as Well as That of Those They Serve

When the Diné seek and receive healing in the form of ceremony, prayer, or medical care, Hózhó principles require them to show gratitude for the healing by presenting a token, a gift, or a ceremonial offering to the healer, which may include the caregiver, nature, holy people, or the Creator.3 This offering not only represents gratitude for the healing received but also serves as a protective shield of energetic intention; the recipient of the healing provides a method to ensure the safety and protection of the healer, whose service is sometimes hazardous and exhausting. This offering demonstrates the recipient's genuine concern for the wellbeing of the healer or caregiver; the health of the individual seeking healing and the health of the healer providing the healing service are both valued within the Hózhó philosophy.

CONCLUSIONS

Recognizing that the 566 federally recognized American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) tribes in the United States are strikingly different in their own culture, geographic region, language, dress, food, ceremonies, philosophies, beliefs, and teachings, we believe that the Diné Hózhó Wellness Philosophy provides an important example of one tribal philosophy on wellness. Sharing the Diné Hózhó philosophy re-introduces this philosophy to the Diné while informing other AI/AN nations, global indigenous cultures, and even nonindigenous people of the world who may benefit from these health-sustaining lifeways. Though this wisdom comes from the Diné, it is offered as a prompting framework for other AI/AN tribes, villages, pueblos, and indigenous people of the world to explore, reexamine, and bring forth their own distinct and innate wellness philosophies as mechanisms for health promotion. For the indigenous populations who may have lost elements or the entirety of their own distinct cultural wisdom due to historical adversities of the past, the 6 tenets of the Hózhó Wellness Philosophy are intertribally relevant because of the vast cultural similarities of our people. In addition, the attributes of the Hózhó philosophy are universally relevant to all individuals and communities or agencies that may be interested in novel or ancient ways to promote the health and wellbeing of the people of the world.

The Hózhó Wellness Philosophy and the Hózhó Resilience Model (Figure) also serve as frameworks through which more biomedically focused healthcare providers can become acquainted with cultural world-views of AI/AN people. It is important to keep in mind that these frameworks provide only a brief glimpse into a differing cultural worldview; integrate this AI/AN cultural wisdom with care and caution. Remember, the AI/AN worldview honors knowledge, stories, and cultural wisdom as sacred entities; when we fold it into our clinical settings, we should do so with honor and respect by including AI/AN cultural experts as part of the planning and implementation process. This cautionary approach communicates our understanding and our respect of the cultural values and ensures accurate implementation of unique culturally tailored approaches for wellbeing and health.

The stunning alignment of integrative nursing principles and the Hózhó Wellness Philosophy illustrates the power of the integrative nursing meta-theoretical perspective and how we can transform healthcare delivery, moving us from parallel healthcare systems (indigenous and biomedical) to a healthcare system that is inclusive and responsive to the needs of our varied populations. AI cultural wisdom is essential to the well-being of the Diné and all indigenous populations who experience considerable health disparities that have not been adequately addressed by current biomedical efforts.22-26 The collective literature on AI/AN culture consistently emphasizes the health-protective nature of shared intertribal cultural wisdom across AI/AN tribes, villages, and pueblos.27-32 And it is critical that we embrace the benefits of cultural wisdom while recognizing the inherent wholeness that can be used as a valuable alternative to or in combination with biomedicine.

Culture is a component of the existential core of a person's identity. Removing someone's cultural wisdom is destructive and leaves an existential hole in the body-mind-spirit, creating vulnerabilities to physical, mental, and social ills. Ongoing refusal of our health-care system to acknowledge the need for and benefit of our cultural practices and health beliefs continues to inflict the trauma of our past, adding to the chronic stress that has resulted from historical traumas and attempts to eradicate our culture.20,21,33-36 Integrative nursing offers the opportunity to re-introduce cultural wellness wisdom, such as the Diné Hózhó philosophy, as a means to improve the health of individuals. Integrative nursing, through the acceptance and validation of indigenous health-sustaining wisdom, contributes to the delivery of effective, authentic, culturally tailored, whole-person and whole-system patient-centered, relationship-based healthcare.

This article began with an excerpt from the The Fundamental Law of the Navajo Nation,9 which reminds us of the diversity of the world while also reminding us of the importance of the individual yet distinct needs of each culture. As individuals, we must never forget how we embody the origins of our cultures and that it is only natural that our healing mechanisms should embody the wealth of rich and diverse healing wisdom. Integrative nursing offers the scientifically based platform that will bring forth increased collaboration among healers and healthcare providers and will transform healthcare delivery that is focused on the health and wellbeing of the biopsychosocialspiritual beings of the world.

Hózhó Nahasdlíí: happiness, health, harmony, peace, wellbeing, beauty, and all that is good—restored.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and Dr Koithan disclosed a grant to her institution from the National Cancer Institute. Dr Kahn-John had no conflicts to disclose.

Contributor Information

Michelle Kahn-John (Diné), College of Nursing, University of Arizona, Tucson, United States..

Mary Koithan, College of Nursing, University of Arizona, Tucson, United States..

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson S, James IK, Attakai M, Attakai MN, Begay EF. Amá Sani dóó Achei Baahané/The office of Diné culture, language, and community services. Cortez, Colorado: Southwest Printing Co; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plawecki HM, Sanchez TR, Plawecki JA. Cultural aspects of caring for Navajo Indian clients. J Holist Nurs. 1994;12(3):291–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell F. Navajo Blessingway Singer: the autobiography of Frank Mitchell, 1881–1967. Albuquerque, NM: UNM Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyman L, Haile B. Blessingway. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witherspoon G. The central concepts of the Navajo world view (I). Linguistics. 1974;119:41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farella JR. The main stalk: a synthesis of Navajo philsophy. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holiday J, McPherson RS. A Navajo legacy: the life and teachings of John Holiday. The civilization of the American Indian. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn-John M. Concept analysis of Dine Hozho: a Dine wellness philosophy. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2010;33(2):113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navajo Nation Courts. Navajo nation code: transcript of the fundamental laws of the Diné: Diné Bi Beehaz'ánii Bitse Siléí CN-69-02 C.F.R. § 201-206 URL http://www.navajocourts.org/dine.htm. Accessed April 9, 2015.

- 10.Kahn-John M. The factor structure of six cultural concepts on psychological distress and health related quality of life in a Southwestern American Indian tribe. Denver: University of Colorado at Denver; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreitzer MJ, Koithan M. Integrative nursing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koithan M. Concepts and principles of integrative nursing, in integrative nursing. Kreitzer MJ, Koithan M. editors Oxford University Press: New York, NY; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Begay DH, Maryboy NC. The whole universe is my cathedral: a contemporary Navajo spiritual synthesis. Med Anthropol Q. 2000;14(4):498–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broome B, Broome R. Native Americans: traditional healing. Urol Nurs. 2007;27(2):161–3, 173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Struthers R, Eschiti VS, Patchell B. Traditional indigenous healing: Part I. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 2004;10(3):141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronilth Jr W. Foundation of Navajo Culture. Tsaile, AZ: Diné College; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simonds VW, Christopher S. Adapting Western research methods to indigenous ways of knowing. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):22–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey PW. Science, research and social change in Indigenous health--evolving ways of knowing. Aust Health Rev. 2009;33(4):628–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denetdale JN. Reclaiming Diné history: the Legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodkind JR, Hess JM, Gorman B, Parker DP. “We're still in a struggle”: Dine resilience, survival, historical trauma, and healing. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(8):1019–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Indian Health Services Disparities Fact Sheet. http://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/. Accessed March 31, 2015.

- 23.Liao Y, Tucker P, Okoro CA, Giles WH, Mokdad AH, Harris VB. REACH 2010 Surveillance for Health Status in Minority Communities --- United States, 2001--2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5306a1.htm. Accessed March 31, 2015. [PubMed]

- 24.Hutchinson RN, Shin S. Systematic review of health disparities for cardiovascular diseases and associated factors among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e80973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connell J, Yi R, Wilson C, Manson SM, Acton KJ. Racial disparities in health status: a comparison of the morbidity among American Indian and U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veazie M, Ayala C, Schieb L, Dai S, Henderson JA, Cho P. Trends and disparities in heart disease mortality among American Indians/Alaska Natives, 1990-2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104 Suppl 3: S359–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeCou CR, Skewes MC, López ED. Traditional living and cultural ways as protective factors against suicide: perceptions of Alaska Native university students. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013. August 5; 72–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming J, Ledogar RJ. Ledogar, Resilience and Indigenous Spirituality: A Literature Review. Pimatisiwin. 2008;6(2):47–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gary FA, Baker M, Grandbois DM. Grandbois, Perspectives on suicide prevention among American Indian and Alaska native children and adolescents: a call for help. Online J Issues Nurs. 2005;10(2):6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grandbois DM, Sanders GF. The resilience of Native American elders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009. September;30(9):569–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stumblingbear-Riddle G1, Romans JS. Resilience among urban American Indian adolescents: exploration into the role of culture, self-esteem, subjective well-being, and social support. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2012;19(2):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wexler L, Joule L, Garoutte J, Mazziotti J, Hopper K. “Being responsible, respectful, trying to keep the tradition alive:” Cultural resilience and growing up in an Alaska Native community. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(5):693–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brave Heart MY1, DeBruyn LM. DeBruyn, The American Indian Holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heart MY, Chase J, Elkins J, Altschul DB. Historical trauma among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: concepts, research, and clinical considerations. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):282–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: a multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(3):316–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Struthers R, Lowe J. Nursing in the Native American culture and historical trauma. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2003;24(3):257–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]