Abstract

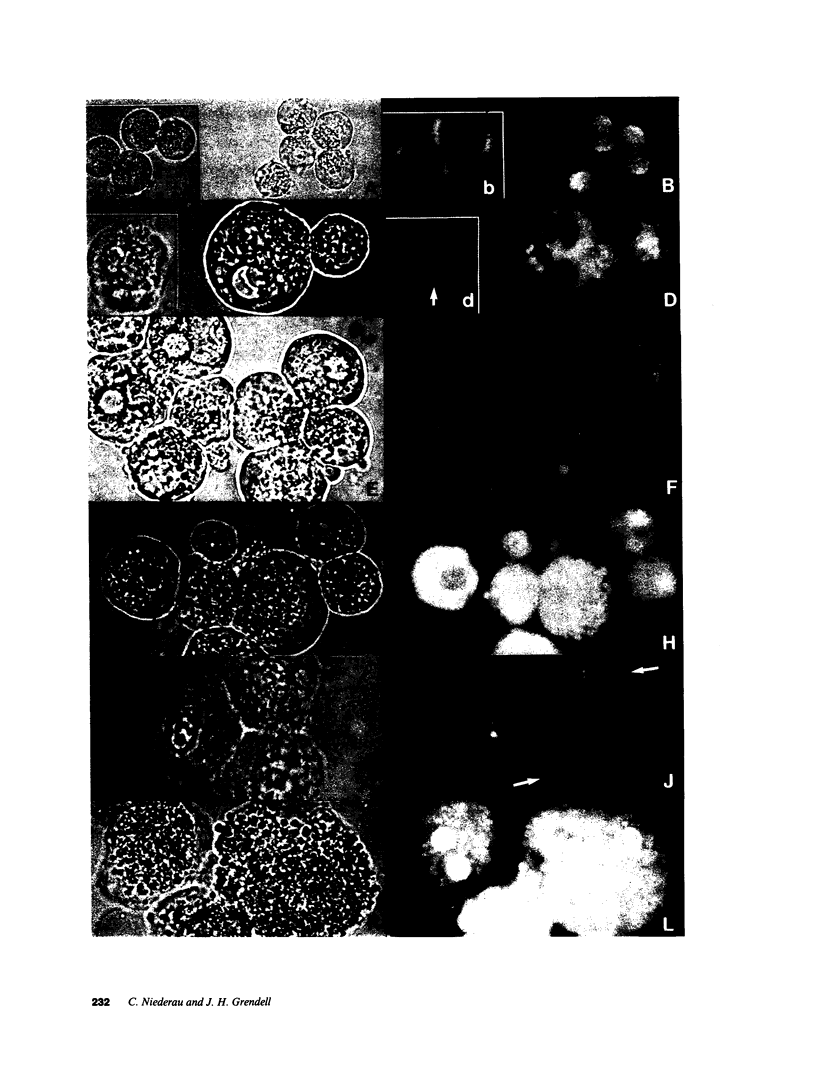

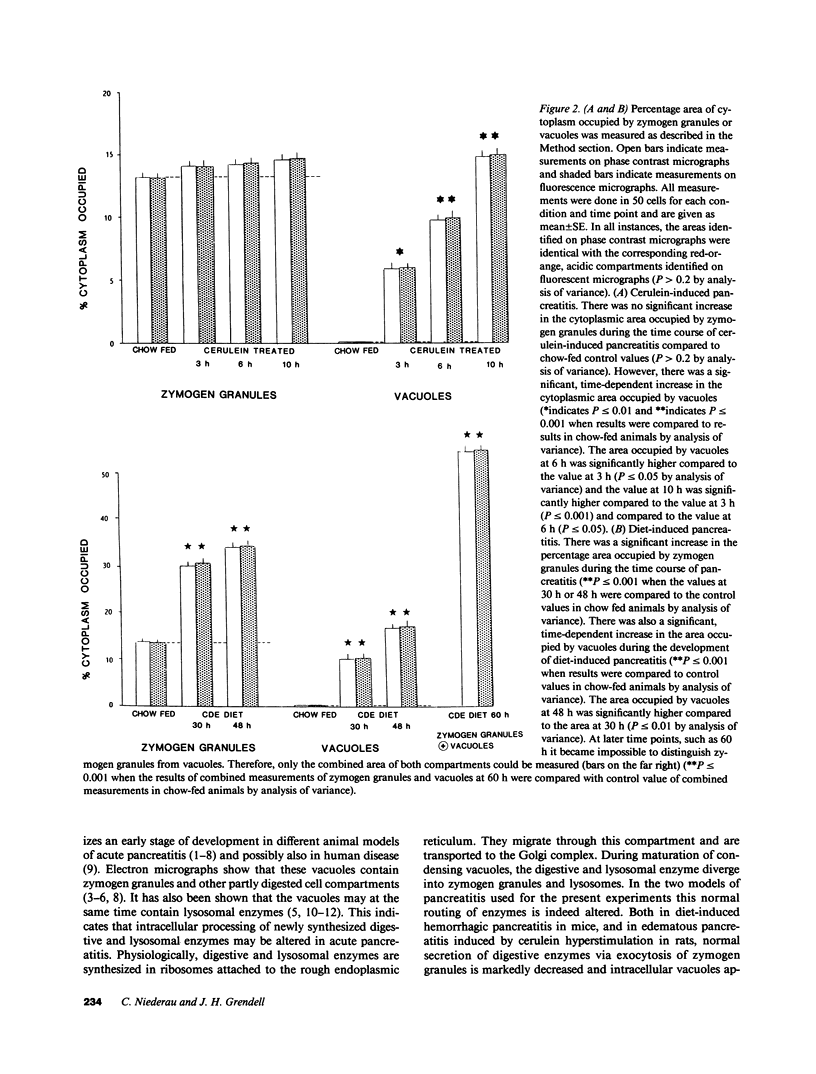

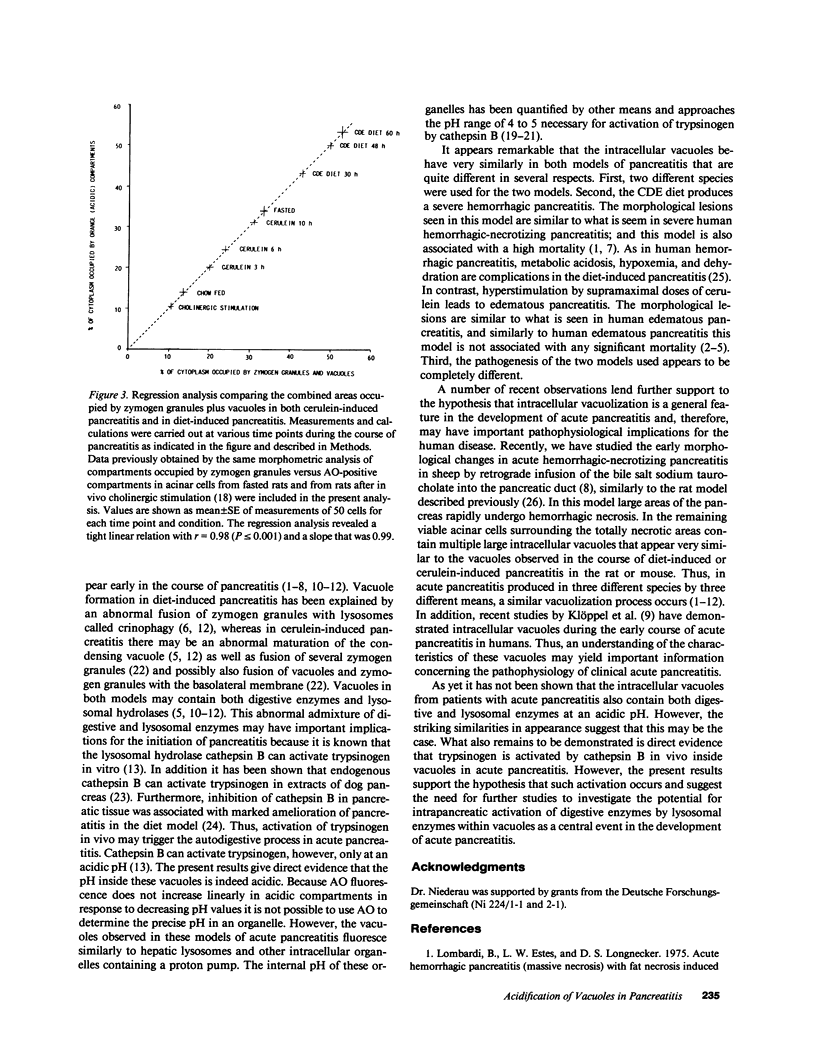

The appearance of vacuoles inside acinar cells characterizes an early stage of development in different models of acute pancreatitis and, possibly, also in human disease. The vacuoles have been shown to contain both digestive and lysosomal enzymes. This abnormal admixture may have important implications for the pathogenesis of pancreatitis because the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin B can activate trypsinogen and may, by this way, trigger pancreatic autodigestion. For the activation process of trypsinogen by cathepsin B, however, an acidic pH is required. This study, therefore, looked for evidence of vacuole acidification in two different models of acute pancreatitis. Edematous pancreatitis was induced in rats by hyperstimulation with cerulein and hemorrhagic pancreatitis was induced in mice by feeding a choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented diet. Pancreatic acinar cells were isolated at different times after induction of pancreatitis and incubated with 50 microM of acridine orange to identify acidic intracellular compartments. As shown in previous work, zymogen granules are the main acidic compartment of normal acinar cells; they remained acidic throughout the course of pancreatitis in both models. Vacuoles became increasingly more frequent in both models as pancreatitis progressed. Throughout development of pancreatitis, vacuoles accumulated acridine orange indicating an acidic interior. Addition of a protonophore (10 microM monensin or 5 microM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone [CCCP] or a weak base (5 mM NH4Cl) completely and rapidly abolished acridine orange fluorescence inside both zymogen granules and vacuoles providing further evidence for an acidic interior. The acidification of vacuoles seen in two different models of pancreatitis may be an important requirement for activation of trypsinogen by cathepsin B and thus for the development of acute pancreatitis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adler G., Hahn C., Kern H. F., Rao K. N. Cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats: increased lysosomal enzyme activity and autophagocytosis. Digestion. 1985;32(1):10–18. doi: 10.1159/000199210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler G., Rohr G., Kern H. F. Alteration of membrane fusion as a cause of acute pancreatitis in the rat. Dig Dis Sci. 1982 Nov;27(11):993–1002. doi: 10.1007/BF01391745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidon S., Ben-David H., Nelson N. ATP-driven proton fluxes across membranes of secretory organelles. J Biol Chem. 1983 Oct 10;258(19):11684–11688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENBAUM L. M., HIRSHKOWITZ A. Endogenous cathepsin activation of trypsinogen in extracts of dog pancreas. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1961 May;107:74–76. doi: 10.3181/00379727-107-26539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENBAUM L. M., HIRSHKOWITZ A., SHOICHET I. The activation of trypsinogen by cathepsin B. J Biol Chem. 1959 Nov;234:2885–2890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hootman S. R., Ernst S. A., Williams J. A. Secretagogue regulation of Na+-K+ pump activity in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol. 1983 Sep;245(3):G339–G346. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.245.3.G339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöppel G., Dreyer T., Willemer S., Kern H. F., Adler G. Human acute pancreatitis: its pathogenesis in the light of immunocytochemical and ultrastructural findings in acinar cells. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;409(6):791–803. doi: 10.1007/BF00710764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike H., Steer M. L., Meldolesi J. Pancreatic effects of ethionine: blockade of exocytosis and appearance of crinophagy and autophagy precede cellular necrosis. Am J Physiol. 1982 Apr;242(4):G297–G307. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.4.G297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampel M., Kern H. F. Acute interstitial pancreatitis in the rat induced by excessive doses of a pancreatic secretagogue. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1977 Mar 11;373(2):97–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00432156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankisch P. G., Winckler K., Bokermann M., Schmidt H., Creutzfeldt W. The influence of glucagon on acute experimental pancreatitis in the rat. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1974 Nov;9(8):725–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi B., Estes L. W., Longnecker D. S. Acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis (massive necrosis) with fat necrosis induced in mice by DL-ethionine fed with a choline-deficient diet. Am J Pathol. 1975 Jun;79(3):465–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi B., Rao K. N. Acute hemorrhagic pancreatic necrosis in mice. Effects of proteinase inhibitors on its induction. Digestion. 1982;23(1):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000198710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederau C., Ferrell L. D., Grendell J. H. Caerulein-induced acute necrotizing pancreatitis in mice: protective effects of proglumide, benzotript, and secretin. Gastroenterology. 1985 May;88(5 Pt 1):1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederau C., Ferrell L. D., Grendell J. H. Experimentelle akute Pankreatitis. Internist (Berl) 1986 Nov;27(11):681–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederau C., Liddle R. A., Ferrell L. D., Grendell J. H. Beneficial effects of cholecystokinin-receptor blockade and inhibition of proteolytic enzyme activity in experimental acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis in mice. Evidence for cholecystokinin as a major factor in the development of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 1986 Oct;78(4):1056–1063. doi: 10.1172/JCI112661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederau C., Van Dyke R. W., Scharschmidt B. F., Grendell J. H. Rat pancreatic zymogen granules. An actively acidified compartment. Gastroenterology. 1986 Dec;91(6):1433–1442. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuma S., Moriyama Y., Takano T. Identification and characterization of a proton pump on lysosomes by fluorescein-isothiocyanate-dextran fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 May;79(9):2758–2762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. N., Zuretti M. F., Baccino F. M., Lombardi B. Acute hemorrhagic pancreatic necrosis in mice: the activity of lysosomal enzymes in the pancreas and the liver. Am J Pathol. 1980 Jan;98(1):45–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer M. L., Meldolesi J., Figarella C. Pancreatitis. The role of lysosomes. Dig Dis Sci. 1984 Oct;29(10):934–938. doi: 10.1007/BF01312483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe O., Baccino F. M., Steer M. L., Meldolesi J. Supramaximal caerulein stimulation and ultrastructure of rat pancreatic acinar cell: early morphological changes during development of experimental pancreatitis. Am J Physiol. 1984 Apr;246(4 Pt 1):G457–G467. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.246.4.G457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. A., Cary P., Moffat B. Effects of ions on amylase release by dissociated pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol. 1976 Nov;231(5 Pt 1):1562–1567. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.5.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro D. J., Fluss S. R., Maxfield F. R. Acidification of endocytic vesicles by an ATP-dependent proton pump. J Cell Biol. 1983 Sep;97(3):929–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]