Abstract

It is unknown whether ductal adenocarcinomas are more aggressive when matched for Gleason score (assigning the ductal component as Gleason pattern 4). Moreover, little is known whether a certain percentage of the ductal component is needed to account for its more aggressive behavior. Of 18,552 radical prostatectomies performed from 1995 to 2008, 93 cases with a ductal adenocarcinoma component were identified. Cases were classified based on their ductal/acinar ratio (<10%; ≥10% and <50%; ≥50%). There was no difference in the distribution of Gleason score 3+4 = 7 versus 4+3 = 7 between ductal and nonductal tumors, such that cases were combined as Gleason score 7. There was no age, race, and serum prostate-specific antigen difference between patients with and without ductal adenocarcinoma. Cases with ductal adenocarcinoma were less likely to be organ confined (36.6% vs 65.6%) and more likely to show seminal vesicle invasion (SVI) (19.3% vs 5.3%), P<0.0001. There was no difference in lymph node metastases or positive margins between cases with and without ductal features. An increasing percentage of the ductal component correlated with an increased risk of extraprostatic extension (P = 0.04) and SVI (P<0.0001). To account for overall different Gleason scores between ductal and nonductal cases, and the effect of differing percentages of ductal features as well, the following analysis was carried out. For Gleason score 7 cases and ≥10% ductal differentiation, cases with ductal features were more likely to have nonfocal extraprostatic extension (64.0%) versus cases without ductal features (34.7%), P = 0.002. In this group, there was no statistically significant difference in SVI or lymph node involvement between Gleason score 7 ductal and nonductal tumors. For Gleason score 7 cases with <10% ductal features, there was no difference in pathologic stage versus nonductal cases. There was no difference in pathologic stage between ductal and nonductal cases for Gleason score 8 to 10 cases, regardless of the percentage of the ductal component. This study shows that ductal adenocarcinoma admixed with Gleason pattern 3 is more aggressive than Gleason score 7 acinar cancer, as long as the ductal component is ≥10%. In cases with a very minor ductal component, these differences are lost. In addition, Gleason score 8 to 10 tumors with ductal features are not significantly more aggressive that acinar Gleason score 8 to 10 cancers in which the pure high-grade tumor, regardless of ductal features, determines the behavior.

Keywords: prostate, ductal adenocarcinoma, stage, extrapro-static extension

Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate is an uncommon variant of prostate cancer that rarely is purely ductal, and is more frequently seen admixed with acinar prostatic carcinoma. As prostatic duct adenocarcinoma typically coexists with higher grade acinar prostate cancer (Gleason score 7 and higher), the convention is to report the ductal component as Gleason pattern 4.6 Correspondingly, prostatic duct adenocarcinoma in radical prostatectomy specimens has been associated with higher stage tumor and worse prognosis.15 However, the association between pathologic stage and the percentage of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma in mixed acinar/ductal adenocarcinomas remains controversial. This study evaluates the relationship of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma and stage, factoring in the grade of the accompanying acinar carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Of a cohort of 18,552 radical prostatectomy specimens performed from 1995 to 2008 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 93 (0.5%) prostatic duct adenocarcinomas were identified. Ductal adenocarcinomas are characterized by tall pseudostratified epithelial cells with abundant, usually amphophilic cytoplasm, in contrast to the cuboidal-tocolumnar single cell layer of epithelium seen with acinar prostatic carcinomas. Prostatic duct adenocarcinomas show a variety of architectural patterns. The most common patterns are papillary and cribriform; as the more recently described high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN)-like prostatic duct adenocarcinoma has a better prognosis akin to Gleason pattern 3, it was excluded from analysis. The cribriform pattern of prostatic duct adenocarcinomas is formed by back-to-back large glands with intraglandular epithelial bridging resulting in the formation of slit-like lumens, differing from the cribriform pattern of acinar adenocarcinoma, which is composed of cuboidal epithelium and a punched-out round lumina. It is not uncommon to find areas of papillary formation admixed with cribriform patterns. Distinguishing features between ductal adenocarcinoma and intraductal carcinoma of the prostate include the former tall pseudostratified columnar epithelium usually with amphophilic cytoplasm, classically arranged in cribriform patterns with slit-like spaces and/or true papillary fronds. In contrast, intraductal carcinoma has cuboidal cells, cribriform patterns with rounded lumina, and micropapillary tufts without fibrovascular cores. In addition, basal cells are generally absent in ductal adenocarcinoma, although occasionally there may be partial retention of basal cells as ductal adenocarcinoma can also spread within prostatic ducts.

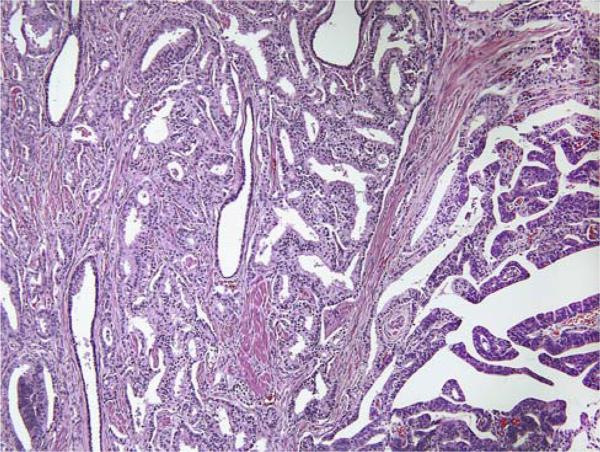

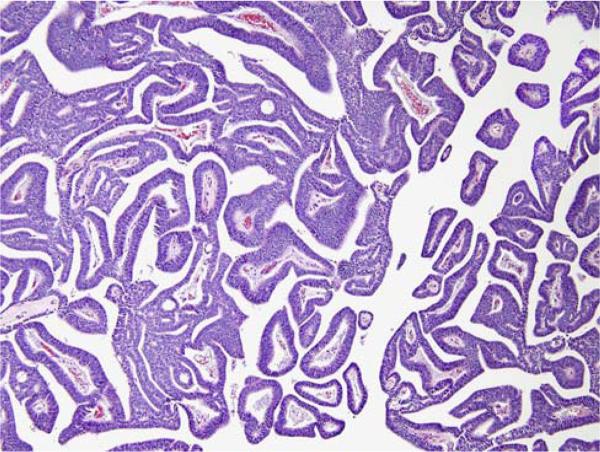

Follow-up was available in 90 patients. The pathology slides were reviewed and the percentage of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma was evaluated. Cases were classified based on their ductal/acinar ratio (<10%; ≥10% and <50%; ≥50%) (Figs. 1, 2).

FIGURE 1.

Mixed ductal (right) and acinar (left) adenocarcinoma.

FIGURE 2.

Pure papillary ductal adenocarcinoma.

The staging variables included extraprostatic extension, positive margins, and involvement of seminal vesicle and lymph nodes. At the apex, if the tumor was in the skeletal muscle, yet not at the inked margin, it was considered as an organ-confined cancer. There was no difference in the distribution of Gleason scores 3+4 = 7 versus 4+3 = 7 between ductal and nonductal tumors. Therefore, such cases were combined as Gleason score 7. Gleason score for the acinar component was assigned using the modified Gleason grading system as reported by the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology Consensus study.6

Statistical tests were carried out using STATA (College Station, TX). T test of the equality of means was used to compare differences between ductal and acinar carcinomas in terms of clinical parameters. Chi square test assessed differences in stage and margins between the 2 cancer types. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. Cox regression analysis was used to assess progression after radical prostatectomy. Progression was defined as a postoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level >0.2 ng/mL.

RESULTS

Clinical data were available in 17,966 prostatic carcinomas, 93 of which had a ductal adenocarcinoma component. Of these, 52.7% had <10%, 38.7% had ≥10 and <50%, and 8.6% had ≥50% ductal component. There was no significant difference in age or serum PSA values between patients with and without the prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma component. The mean age of patients with any prostatic duct adenocarcinoma component compared with those with purely acinar cancer was 58.2 years and 59.5 years, respectively. The mean PSA level was 6.9 ng/mL for purely acinar carcinoma compared with 7.7 ng/mL for cases with a mixed prostatic duct adenocarcinoma component.

Cases with ductal adenocarcinoma were less likely than acinar carcinoma to be organ confined (36.6% vs. 65.6%) and more likely to have seminal vesicle invasion (19.3% vs. 5.3%), P<0.0001. Although prostatic duct adenocarcinoma was associated with a higher risk compared with acinar carcinoma of lymph node involvement (5.3% vs. 2.4%) and margin positivity (20.4% vs. 14.4%), the differences did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1 and P = 0.06, respectively). An increasing percentage of the ductal component correlated with an increased risk of extraprostatic extension (P = 0.04) and seminal vesicle invasion (P<0.0001) (Table 1), yet not lymph node metastases (P = 0.3) or involvement of the margin (P = 0.8).

TABLE 1.

Correlation of Extraprostatic Extension and Seminal Vesicle Involvement With Increasing Ductal Component

| Percent Ductal Component | Extraprostatic Extension (%) | Seminal Vesicle Invasion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| < 10 | 40.8 | 16.3 |

| ≥ 10-50 | 58.3 | 11.1 |

| ≥ 50 | 75.0 | 75.0 |

To account for the overall different Gleason scores between ductal and nonductal cases and the effect of differing percentages of ductal features, analysis of stage was separately carried out on the prostatic carcinoma cases with Gleason scores of 7 and ≥8. For Gleason score 7 tumors, cases with ≥10% admixed ductal features were more likely to have nonfocal extraprostatic extension compared with purely acinar cancers, P = 0.002 (Table 2). In these cases, there was no statistically significant difference in seminal vesicle invasion or lymph node involvement between ductal and nonductal tumors (Table 2). Although Kaplan-Meier curves showed a higher risk of biochemical progression for men with Gleason score 7 and >10% ductal component compared with Gleason score 7 cases with 0% to 10% ductal features, this did not reach statistical significance using Cox regression analysis. The mean follow-up for the 44 men with Gleason score 7 and >10% ductal component with and without progression was 3.9 years and 5.6 years, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Pathologic Stage in Ductal Adenocarcinomas With >10% Ductal Component Versus Gleason Score 7 Acinar Adenocarcinoma

| Acinar Gleason 7 | Ductal ≥ 10% | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraprostatic extension | 2132/6150 (34.7%) | 16/25 (64%) | 0.002 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | 531/6168 (8.6%) | 3/25 (12%) | 0.5 |

| Lymph node metastases | 235/6170 (3.8%) | 2/25 (8.0%) | 0.3 |

For Gleason score 7 cases with <10% ductal features, there was no difference in pathologic stage versus nonductal cases. There was also no difference in pathologic stage between ductal and nonductal cases for Gleason score 8 to 10 cases, regardless of the percentage of the ductal component.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma may be difficult, especially in cases when there is admixed cribriform acinar adenocarcinoma or when associated with HGPIN. There can be an overlap between the morphology of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma and the micropapillary and cribriform patterns of HGPIN. Although HGPIN may show micropapillary formation, it lacks the true papillary structures of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma. Cribriform HGPIN is uncommon and contains round-oval nuclei and punched-out round lumina, in contrast to columnar nuclei and slit-like lumina of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma. It is also difficult to distinguish prostatic duct adenocarcinoma from the more recently described entity of intraductal carcinoma.9,14 Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate usually reflects intraductal extension of infiltrating high-grade acinar carcinoma, although rarely it may represent a de novo intraductal growth of solid or cribriform acinar cancer without an infiltrating component. Intraductal carcinoma is an acinar proliferation with round nuclei, whereas prostatic duct adenocarcinoma is lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium. There is also overlap among these entities with immunohistochemistry for basal cell markers. Although HGPIN usually has an interrupted basal cell layer, occasional glands of HGPIN may lack basal cells immunohistochemically. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate by definition has a basal cell layer.17 Most ductal adenocarcinomas lack basal cells, yet 31.4% may show a patchy basal cell layer as the cancer involves ducts and acini.10

Owing to the difficulty of diagnosing prostatic duct adenocarcinoma, it is difficult to get accurate numbers as to its incidence. Older studies before the recognition of intraductal carcinoma may have confounded data by including such cases. Bock and Bostwick2 reported that ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate was admixed with acinar prostatic carcinoma in approximately 17 of 338 radical prostatectomy specimens (5%). However, some of their images of ductal adenocarcinoma would be considered to be intraductal acinar carcinoma in current practice. In a study by Samaratunga et al,15 12.7% of 268 radical prostatectomy specimens had a prostatic duct adenocarcinoma component. In their study, the patterns of ductal adenocarcinoma included papillary, cribriform, solid, and invasive glandular patterns. The description of the so-called “invasive glandular” pattern is identical to the HGPIN such as ductal adenocarcinoma, which was excluded in this study.

In the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data looking at 17 cancer registries from multiple cities and states, 371 out of 442,881 (0.08%) were recorded as ductal adenocarcinoma.12 Using strict criteria, we found that the frequency of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma in our series was 0.5%. Cases of mixed ductal/acinar cancers in which the ductal component is focal may be more difficult to identify. This study showed that when the ductal component is <10%, it has no effect on prognosis, such that the underdiagnosis of focal ductal features at radical prostatectomy has no adverse consequences for the patient. In the only other study addressing this issue, the results were at odds with this study. Samaratunga et al15 found that the proportion of ductal adenocarcinoma did not significantly modify the strength of the observed association with pathologic stage.

Our understanding relating to the prognosis of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma has evolved since its initial description in 1967.11 In the earlier literature, it was stated that ductal adenocarcinomas can grow centrally into the urethra and may infiltrate locally but will rarely metastasize.16 Subsequently, several series in the 1980s concluded a contradictory fact with description of advanced disease at radical prostatectomy and a high likelihood of failure after surgery. However, these early series predated the widespread use of serum PSA to screen prostate cancer.3–5,7,8,13 In a study carried out at our institution in 1991, we reviewed 15 cases with ductal adenocarcinoma at radical prostatectomy.5 Compared with acinar cancers of similar clinical stage, ductal cancers were large and of an advanced pathologic stage with 93% having extraprostatic extension, 47% having positive margins, 40% having seminal vesicle invasion, and 27% positive for lymph nodes involvement. Palpable disease was present in 12 of the 15 men, with preoperative serum PSA testing conducted in only 73% of the cases. In another study published in 1999, we analyzed 20 ductal adenocarcinomas diagnosed on needle biopsy treated by radical prostatectomy.4 Extraprostatic extension was seen in 63%, positive margins in 20%, seminal vesicle invasion in 10%, and none had positive lymph node involvement. Postoperative progression occurred earlier when compared with a cohort of acinar cancers. Only 62% had preoperative serum PSA data and only 23% had nonpalpable disease. In the contemporary era, there have been limited studies on the prognosis of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma. Aydin et al1 from the Cleveland Clinic recently reported a series of 13 men treated by radical prostatectomy, of whom 4 had Gleason score 7 and 8 had Gleason score ≥8 cancer. Extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and lymph node metastases were present in 7, 6, and 2 cases, respectively. Samaratunga et al15 evaluated 34 cases of ductal adenocarcinoma and 234 acinar cancers treated by radical prostatectomy. Ductal adenocarcinomas had a higher likelihood of having extraprostatic extension (73%) relative to acinar carcinoma (32.9%), even adjusting for tumor volume and Gleason score >7. In an analysis of the SEER database, which represents pooled pathology reports from multiple institutions in different states, 371 ductal adenocarcinomas were compared with 442,881 acinar cancers. A major weakness of the latter study is that although the number of cases is large, the cases have not been reviewed by urological pathologists. As an example of the poor quality of some of the SEER data, Gleason score was not even recorded until 2004. Consequently, only 29.6% of the ductal cancers have a Gleason score, 19% of which were assigned a Gleason score of 6 that further calls into question the accuracy of the data. Recognizing these deficiencies, ductal cases were more likely to present with distant metastasis (12% vs 4%) and lower serum PSA levels.12

This study shows that ductal adenocarcinoma admixed with Gleason pattern 3 is more aggressive than Gleason score 7 acinar cancer without a ductal component, as long as the ductal component is ≥10%. In cases with a very minor ductal component (<10%), these differences are lost. The more extensive ductal component was associated with the higher likelihood of extrapro-static extension and seminal vesicle invasion. We could not show a statistically significant difference in prognosis after radical prostatectomy in this cohort; it may be due to the relatively small number of cases (n = 44). In contrast, Gleason score 8 to 10 tumors with ductal features do not seem to be significantly more aggressive than acinar Gleason score 8 to 10 cancers in which the high-grade tumor, regardless of ductal features, determines the behavior.

There are several limitations in this study. Our cohort represents patients who underwent radical pros-tatectomy. There is a potential for selection bias; cases in which more advanced ductal adenocarcinomas would not have been included within our analysis as they would have not been considered as surgical candidates. The other limitation is that although all the ductal adenocarcinomas were rereviewed to ensure that the diagnosis was accurate and to calculate the percentage of the ductal component, Gleason pattern 4 acinar cancers without a ductal component were not reviewed. Consequently, it is not possible to determine whether our findings are applicable to all the Gleason 4 patterns. It may be that Gleason score 7 cancer, in which the acinar Gleason pattern 4 is cribriform, has the same adverse prognosis of ductal adenocarcinoma. The worse prognosis for Gleason score 7 tumors with ≥10% ductal component may only apply to acinar Gleason score 7 cancers with fused and poorly formed glands. Additional studies are needed to address this issue. On the basis of the available data, it is imperative to mention the presence and the percentage of prostatic duct adenocarcinoma in radical prostatectomy specimens, especially when the Gleason score is 7.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aydin H, Zhang J, Samaratunga H, et al. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate diagnosed on transurethral biopsy or resection is not always indicative of aggressive disease: implications for clinical management. BJU Int. 2010;105:476–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock BJ, Bostwick DG. Does prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma exist? Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:781–785. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199907000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bostwick DG, Kindrachuk RW, Rouse RV. Prostatic adenocarcinoma with endometrioid features: clinical, pathologic, and ultra-structural findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:595–609. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinker DA, Potter SR, Epstein JI. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate diagnosed on needle biopsy: correlation with clinical and radical prostatectomy findings and progression. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1471–1479. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen WN, Steinberg G, Walsh PC, et al. Prostatic duct adenocarcinoma: findings at radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 1991;67:2118–2124. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910415)67:8<2118::aid-cncr2820670818>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein JI, Woodruff JM. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate with endometrioid features: a light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of ten cases. Cancer. 1986;57:111–119. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860101)57:1<111::aid-cncr2820570123>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene LF, Farrow GM, Ravits JM, et al. Prostatic adenocarcinoma of ductal origin. J Urol. 1979;121:303–305. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56763-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo CC, Epstein JI. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy: Histologic features and clinical significance. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1528–1535. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herawi M, Epstein JI. Immunohistochemical antibody cocktail staining (p63/HMWCK/AMACR) of ductal adenocarcinoma and Gleason pattern 4 cribriform and noncribriform acinar adenocarcinomas of the prostate. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:889–894. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213447.16526.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melicow MM, Pachter MR. Endometrial carcinoma of prostatic utricle (uterus masculinus). Cancer. 1967;20:1715–1722. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196710)20:10<1715::aid-cncr2820201022>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan TM, Welty CJ, Vakar-Lopez F, et al. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate: increased mortality risk and decreased serum prostate specific antigen. J Urol. 2010;184:2303–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ro JY, Ayala AG, Wishnow KI, et al. Prostatic duct adenocarcinoma with endometrioid features: immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:301–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson BD, Epstein JI. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate without invasive carcinoma on needle biopsy: emphasis on radical prostatectomy findings. J Urol. 2010;184:1328–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samaratunga H, Duffy D, Yaxley J, et al. Any proportion of ductal adenocarcinoma in radical prostatectomy specimens predicts extra-prostatic extension. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tannenbaum M. Endometrial tumors and/or associated carcinomas of prostate. Urology. 1975;6:372–375. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(75)90773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavora F, Epstein JI. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia-like ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1060–1067. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318160edaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]