Abstract

Objective

This article describes the process undertaken to identify and validate behavioral and normative beliefs and behavioral intent of men between the ages of 45–70 with regard to participating in shared decision-making in medically uncertain situations. This article also discusses the preliminary results of the aforementioned processes and contemplates potential future uses of this information which may facilitate greater understanding, efficiency and effectiveness of doctor-patient consultations.

Design

Qualitative Study using deductive content analysis

Setting

Individual semi-structure patient interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached. Three analysts read the transcripts and developed a list of codes.

Subjects

25 subjects drawn from the Philadelphia community.

Measurements

Qualitative indicators were developed to measure respondents’ experiences and beliefs related to behavioral intent to participate in shared decision-making during medically uncertainty. Subjects were also asked to complete the Krantz Health Opinion Survey as a method of triangulation.

Results

Several factors were repeatedly described by respondents as being essential to participate in shared decision-making in medically uncertainty. These factors included past experience with medically uncertainty, an individual’s personality, and the relationship between the patient and his physician.

Conclusions

The findings of this study led to the development of a category framework that helped understand an individual’s needs and motivational factors in their intent to participate in shared decision-making. The three main categories include 1) an individual’s representation of medically uncertainty, 2) how the individual copes with medically uncertainty, and 3) the individual’s behavioral intent to seek information and participate in shared decision-making during times of medically uncertain situations.

Introduction

Decisions are “the acts that turn information into action.” [1] The need to make accurate and effective health decisions is inescapable, regardless of whether the patient exhibits a medical condition which threatens his/her life or a psychological condition which threatens his/her quality of life, and regardless of whether the research evidence is robust or lacking. Uncertainty nearly always enters the equation, as it is frequently a component of medical reasoning.[2–4] A summary of recent trends in medical reasoning and knowledge reported that nearly half (47%) of all treatments for clinical prevention or treatment were of unknown effectiveness and an additional 7% involved an uncertain tradeoff between benefits and harms.

Shared decision-making, (SDM) has been identified as an effective technique for managing uncertainty involving two or more parties. [5] Despite the identification of SDM as an effective technique, it is under circumstances of medically uncertainty where even less shared decision-making is practiced between a physician and patient. [5–8]

How do we move towards a solution to the ironic situation where although shared decision-making has been proven as an optimal solution for medically uncertain situations, it is frequently in medically uncertain situations where SDM is rarely practiced? The communication and relationships observed between patients and physicians when SDM is practiced requires a deeper understanding and incorporation of human behavioral elements in order to successfully achieve the benefits SDM has to offer.

There is substantial evidence that positive attitudes, subjective norms, and past experiences correlate with positive behavioral intent.[9–16] Based on this correlation, it can be deduced that the intent to engage in a behavior leads to the behavioral action. Behavior is defined as the action or reaction of an entity, human or otherwise, to situations or stimuli in its environment. [17] It is a key concept in understanding the driving forces and cause & effects of many issues. In particular, the construct of behavioral intent has successfully predicted behavioral action in other health situations.[9–16] However, behavioral intent has never been studied to understand the behavioral action or preference for shared decision-making. The purpose of this ethnographic study was to do just that: to understand the factors involved in a patient’s behavioral intent to participate in shared decision-making in the event of a medically uncertain situation.

Background

Behavioral Intent

Behavioral intent is the basis for the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). [18,19] This has “received considerable and, for the most part, justifiable attention within the field of consumer behavior…not only does the model appear to predict consumer intentions and behavior quite well, it also provides a relatively simple basis for identifying where and how to target consumers’ behavioral change attempts” [20] It has also been used to successfully predict and explain a wide range of health behaviors and intentions – and findings have been used to develop behavior change interventions. [21–25] A given patient and a given physician have a unique behavioral action model and approach to managing information that impacts a prevention practice or clinical intervention for a given patient. [18,19] Behavioral intention is the most proximal determinant of behavior and its best predictor. [1, 14,17,26,27] Individuals with stronger intentions to engage in a particular behavior are more likely to engage in that behavior than individuals with weaker intentions.

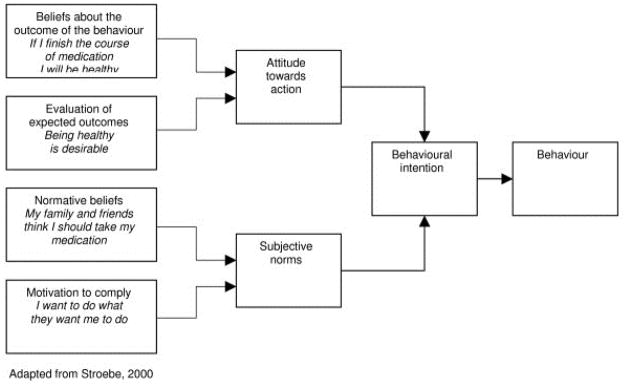

In order to understand and characterize the behavioral intent of the patients, elements from the TRA were used. The TRA, focuses on individual motivational factors as determinants of the likelihood of performing a specific behavior. In other words, a person’s behavioral intention, (BI) depends on the person’s attitude (A), about the behavior and subjective norms, (SN). As such, BI = A + SN. Therefore, if an individual aims to engage in a behavior then it is likely that he will do so. [18,28] A person’s intentions are, themselves, guided by two things: the person’s attitude towards the behavior and the subjective norm. [18,19]

The point of TRA is that intention predicts behavior (behavioral intentions predict use). This theory focuses on identifying the determinants of intentions – e.g. attitude, social influences and condition. [18, 19, 28, 29]

Behavioral intention measures a person’s relative strength of intention to perform a behavior.

Attitude consists of beliefs about the consequences of performing the behavior multiplied by his or her valuation of these consequences.

Subjective norm is a combination of perceived expectations from relevant individuals or groups along with expectations to comply with these expectations.

The theory distinguishes between attitude toward an object and attitude toward a behavior with respect to that object.[18,19,29–31] An example would be a patient’s attitude toward the object of prostate cancer versus his behavior of seeking screening for prostate cancer. The attitude toward a behavior is a much better predictor of that behavior than the attitude toward the target at which the behavior is directed. [32] For example, the attitude toward prostate cancer is expected to be a poor predictor of prostate cancer screening behavior, whereas attitude toward seeking prostate cancer screening is considered to be a better predictor. This theory provides a framework for identifying key behavioral and normative beliefs that affect an individual’s behavior. Applying this theory, interventions can be designed to target and change these beliefs or the value placed upon them, in turn affecting attitude and subjective norm, and leading to a change intention and behavior. [31] Simply stated, a reasoned action approach to the explanation and prediction of social behavior assumes that people’s behavior follows reasonably from their beliefs about performing that behavior. [32]

Methods

Research Design

The research protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by The Institutional Review Boards for University of Texas and University of Pennsylvania to ensure the protection of human subjects was properly addressed and complied with due federal guidelines in protection of confidentiality and privacy. Subjects were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time, and that their interview would be audio-recorded. Subjects were informed that only first names would be use during the interviews in order to maintain confidentiality. No identifying information regarding subject participants was included in any transcripts.

Interview content

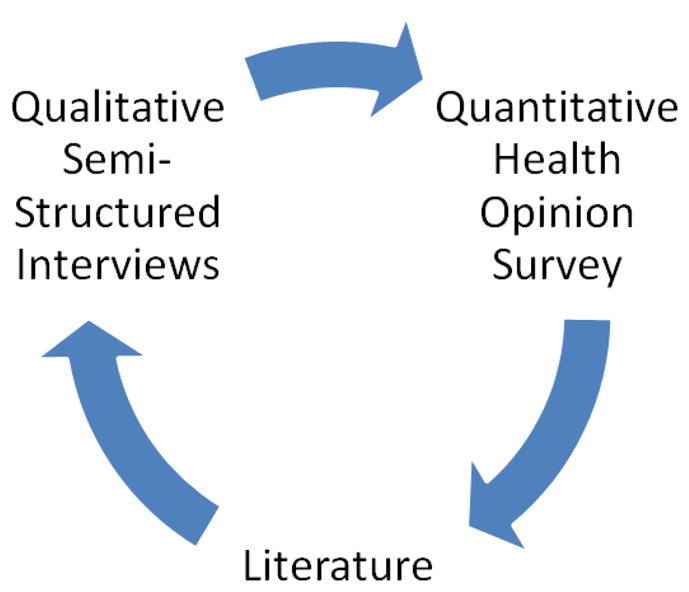

The content for the semi-structured interviews was developed from a) literature review of shared decision-making, medical uncertainty, and theory of reasoned action; and b) data analysis of a secondary retrospective ethnographic study involving medical encounters between men (ages 45–70) and their primary care physicians. The figure below shows the interview schedule for this project.

Questionnaire – Krantz Health Opinion Survey (KHOS)

Following the interview, a questionnaire based on Krantz et al. was given to measure preference for healthcare information and active involvement in healthcare. [33] Extensive testing was undertaken to establish the instruments’ validity and reliability. [33] The instrument has two subscales, one measuring information preference (I-Scale) and the second measuring the degree of behavioral involvement (B-Scale). The I-Scale contains seven items measuring desire to ask questions and desire to be informed about medical decisions. The following is an example of a statement found on the I-Scale: “I usually don’t ask the doctor or nurse many questions about what they’re doing during a medical examination.” The B-Scale contains nine statements that measure attitudes toward self-treatment and active behavioral involvement of patients with their care. An example of the B-Scale: Clinics and hospitals are good places to go for help, since it is best for medical experts to take responsibility for healthcare.” The scale yields a total score, which is a composite of the two subscales. The binary, agree-disagree format was so designed that the high scores represent positive attitudes toward self-directed or informed treatment.[33]

The study included African-American and Caucasian men between the ages of 45 and 70 without any history of prostate cancer. A purposive sampling strategy was used to select participants from the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center meeting eligibility criteria.

Setting

Recruitment and Data Collection

Recruitment

Patients were recruited via flyers placed around the University of Pennsylvania medical center. If interested, potential subjects were asked to call a number to schedule an time for an interview. Calls were then screened by research assistants who asked questions to ensure eligibility. Once eligibility was established, a date and time was arranged for the subject to come for the interview. A day before each interview, the research assistant would call the subject as a reminder of date, time and location.

Site selection

The University of Pennsylvania medical school campus was chosen as the site for the semi-structured interviews. A room in the Department of Epidemiology was reserved for the interviews.

Semi-Structured Interviews

A semi-structured, open-ended interview guide developed by the investigator guided all the discussions. This interview was reviewed by four faculty members, three from the School of Biomedical Informatics at the University of Texas Health Science Center, and one from the department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, as well as two nursing research assistants. This process ensured that the questions being asked were structured in a manner that a) facilitated dialogue among subjects, b) did not lead subject responses, and c) maximized the likelihood that behavioral and normative beliefs could be elicited in regards to shared decision-making in medically uncertain situations.

Each interview was conducted by the research coordinator. The responsibilities of the research coordinator were to read consent forms to subjects at the beginning of the interviews; to ensure appropriate forms were distributed, signed, and collected; to take notes during the interviews; and to ensure that all notes and tapes were properly labeled at the end of each interview.

Transcription

Since this project was the research coordinator’s dissertation work, she was responsible for transcribing each interview verbatim. In order to ensure the quality of this quantitative research, regular debriefing sessions occurred throughout the project with the research coordinator and two nursing research assistants.

Data Analysis

The semi-structured interviews were analyzed using a qualitative, deductive content analysis. Qualitative deductive content analysis is “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns. [34] This type of analysis is most often used to analyze interview transcripts in order to uncover or model people’s information related to behaviors and thoughts. [35] The following steps were taken during the content analysis process.

Step 1: Prepare the Data

The content analysis began during early stages of the interview process in which the researcher alternated between data collection and concept development. This method helped to guide the data collection from the interviews toward sources that were useful for addressing the research question of understanding behavioral intent for shared decision-making in medically uncertain situations. [36] The interview data was transcribed into written text. For the sake of this project, the main questions from the interview guide were transcribed verbatim rather than summarily.

Step 2: Define the Unit of Analysis

Unit of analysis is the basic unit of text that is classified during the content analysis. Messages were unitized before they were coded. Defining the coding unit is one of the most fundamental and important decisions. [37] An individual theme is usually used as the unit for analysis rather than physical linguistic units, such as words or sentences. In this case, the theme used as the coding unit was a patient’s behavioral intent (attitudes, subjective norms) to practice shared decision-making in medically uncertain situations.

Step 3: Develop Categories and a Coding Scheme

The categories and coding scheme was derived from three sources: the literature, the data, and the theory of reasoned action. For this study, a deductive reasoning approach was used since the theory of reasoned action was used as the basis for the inquiry. A deductive content analysis is used in cases where one wishes to re-test existing data or theories in a new context [38] Therefore, the initial list of coding categories was generated from this theory. However, this theory was modified during the course of the analysis as new categories emerged. [36] The next step was to develop a categorization matrix, followed by the development of a coding manual (to ensure coding consistency). Category names, their respective definitions and rules for assigning codes were included in the manual. Any doubts or confusion regarding the definitions of categories, coding rules, or categorization were discussed and resolved in regular debriefing sessions. After the categorization matrix and coding manual were developed, all the data was reviewed for content and coded according to identified categories.

Step 4: Code the Text

Step 5: Assess Coding Consistency

Rechecking the consistency of the coding was performed at various times throughout the coding process, and was executed by the research coordinator and the two nursing research assistants.

Step 6: Draw Conclusions from the Coded Data

In this step, the properties and dimensions of the categories were explored to identify relationships between categories and uncover themes and patterns.

Results

The data analysis began after the collection of data from the first subject and continued until saturation. Data saturation was considered to be attained when no new information related to the research question resulted from the subject interviews.

Demographic data were summarized as descriptive statistics. A total of 25 men were interviewed, among them 16 (63%) were African American, and 9 (38%) were Caucasian males. The mean age of participants was 57. The table below shows the full demographic data of the participants.

Main Themes

A few main themes were repeatedly mentioned by the subjects as being important in the intention to participate in shared decision-making in the event of a medical uncertainty: past experience, personality, and physician-patient relationship. As illustrated in the following paragraphs, these themes overlap but each emphasizes a distinct characteristic involved in decision-making participation in medically uncertain situations. These themes were used to ultimately construct the category framework as a way to provide a comprehensive, systematic exploration of variables and process associated with uncertainty and behavioral intent outcomes for shared decision-making.

Past experience with medical uncertainty

Well, is anything really ever certain? I mean you can get all the information you want, and the md can tell you % that he’s read or witnessed, but you never know. You know the saying “Man plans, and God laughs?” haha its true. Subject 17

“Well after that it changed my outlook, I was more invested with everything that was going on. So yes, my intent would be more towards finding out what is going on in all future events.” Subject 5.

However, even though subjects with past experiences with medical uncertainty stated that their intent to participate increased after the experience, their decision-making preference did not experience a a radical change. Rather, the patient gained a more realistic idea of how to handle information and decision-making in situations of medical uncertainty.

Subject 5 describes his past experience with medical uncertainty, exhibiting openness to shared-decision making:

I mean I will ask questions, and want my physician to give me all the choices and options, but I feel - it has actually calmed me down more in turns of understanding that some things cannot be predicted, it’s okay to get information from your family, internet, and doctor; be open with your doctor; but I will still have him make the ultimate decision. I think that my participation in that extent is moving toward more of a shared decision-making aspect. I’m not going to go 180 and say now that I know best and I am the expert. But I feel more calm with uncertain situations that its okay to ask questions, and then listen to what your doctor has to say.

Subject 22 describes his lack of past experience, focusing on his anxiety and exhibits hyper-vigilance in his approach towards addressing the situation:

I’ve never been involved in a medical uncertain situation, that you say. I don’t think I know anyone in my family that has as well. I think I would be a little freaked, so I’d get information from the internet, probably get a second and third opinion, and then make the ultimate the decision on my own. If it’s uncertain, then the docs don’t know what to do either. I might as well do it.

The lack of past experiences with medically uncertain situations resulted in increased anxiety in respondents’ answers, and an increased desire and intent to move toward a completely hyper-vigilant information seeking and decision-making behavior.

Patient/Physician relationship

Even subjects who had a trusting relationship with their physician stated that their intent to participate in SDM in an event of a medically uncertainty was not very likely. They indicated that they would prefer their physicians to tell them about the uncertainty and to let them know the options and concerns, but the final decision should be made by the physician.

Subject 12:

I don’t expect he would ask for my opinion, but hell explain it to me and ask if I have any questions.

Subject 9

I don’t want to say that participating in medical decisions is pointless and a waste of time. hahah but I don’t really do it much, because of my relationship with my doc. He’s great, and he knows everything about me already.

Subject 3:

I do want to know choices and options, and my doc’s recommendations but then they make final decision. He’s the expert, afterall. I know he is human and not perfect, but I trust him to look after my best interest.

On the other hand, subjects who did not have a close personal relationship with their physician stated that their intent to participate in SDM was very likely.

Subject 15:

My future intent is to be more proactive in my healthcare especially if there is some ambiguity. You have to learn how the system is. You have to push things along and follow through, unfortunately in medicine that is not there a lot of the time. Doctors have so many patients, but there is only one you – and you need to look after yourself, because to doctors, you are just another number.

Subject 19:

It’s not that I don’t trust my physician, but sometimes I think they are looking after their own pockets. I would just always want to protect myself, but asking and getting enough information as possible from doctors, but in the end make the final decision myself.

Personality type

Subjects also stated that their distinct personalities definitely influence how they felt about medical uncertainty, and that it also influenced their preference for information-seeking and behavioral intent to participate the shared decision-making process.

Subject 6:

“When it comes to something that you cannot predict – it’s not necessarily that I am ok, it’s just such a difficult field that I’m a little bit more lenient when it comes to wanting to know everything upfront they tell you we have to open you up to see what we find, ok there is nothing more we can do – so I’m okay with that standpoint.”

Subject 24:

“It has to do with your psych and personality as well. If you are an anxious person, the idea of uncertainty will drive you crazy. I feel that uncertainty is like death. It is the unknown. I think those that accept the concept of death and deterioration, can more easily accept the everyday concept and aspect of medical uncertainty.

Subject 8:

I’m a total hypochondriac, if I have a shoulder pain, I think its cancer. (haha). I guess uncertainty is another thing to worry about.

Subject 20:

Now, I would rather hear what the uncertainty is, and so it is what it is at that point. I’m not going to go crazy because I understand now that everyone will go through some medically uncertainty one time or another in their lives. You have people around you to support you (doctors, nurses, family) no one is trying to hurt you. You are all on the same side.

Category Framework

A category framework was developed from the content analysis,. The objective of this framework was to guide and generate research on individual’s representation of medical uncertainty, and their behavioral intent to participate in medical decision-making. The emerging framework based on this study’s content analysis can be seen in the figure below (Diagram 1). There are three inter-linked elements in the framework that combine to describe and determine sources of individual differences in relation to behavioral intent to participate in shared decision-making in the event of a medically uncertain situation.

Category A – Representation

In this first category, an individual labels medically uncertain situations using the factors of general knowledge, personal experience, and personality. General knowledge includes scope of knowledge compared to medical professional; access to information including internet, family, health professionals; and interpretation and trust of information. Personal experience includes past experiences with medical uncertainty, a family member’s past experience with medical uncertainty, and individual’s relationship with his physician. Personality includes anxiety, hypochondriac, adoptive, low-stress, dependent, independent, and trusting personality. The three categories of general knowledge, personal experience and personality provide the structure from which individuals form opinions and conceptualize medical uncertainty.

Category B – Coping

Having addressed the structure patients use to represent uncertainty,, the second category involved the methods in which the individual copes with the concept of medical uncertainty. An individual can have difficulty or can have no difficulty with coping. Those individuals who have difficulty coping are considered as being in the active Information Seeking group. This group is characterized by having negative past experience(s) with medical uncertainty, having no experience with medical uncertainty, and/or having a lack personal or trusting relationships with medical professionals. Meanwhile, those individuals who do not have difficulty coping with medical uncertainty are considered as being in the passive, Information Acceptance group. This group is characterized as having past experience with medical uncertainty, having close relationship(s) with their physician, and/or having a relaxed or low-stress personality.

Category C – Behavioral Intent

The final category within the framework is the behavioral intent to practice shared decision-making when medical uncertainty is involved. From this study, a positive correlation was identified between difficulty coping with uncertainty and positive intent to actively participate in SDM. The subjects in this group were those individuals without prior experience with medical uncertainty and without a strong or trusting relationship with their physicians. Further, the individuals in this group were more likely to actively seek information and medical alternatives and to be involved in the final medical decision. Conversely, the subjects who were better at coping with uncertainty were passive participants in the decision-making process. Categorization in this group does not necessarily indicate the level of desire to be involved. Rather, it was observed that subjects in this group were content with the information provided or otherwise available to them, and accepted their role as a passive participant, ultimately deferring final decisions to the healthcare professional.

Krantz Health Opinion Survey

Scores from the KHOS Health Opinion Survey were split into high and low information seeking, and high and low behavioral involvement groups with a median split and were treated as interval data. The KHOS-I scores for this sample ranged from 1 to 7 and the mean was “4.16 (Std Dev =1.67). The KHOS-I scores were divided into low and high information seeking groups with a median split. Likewise, the KHOS-B scores for this sample ranged from “1 to 5” and the mean was 2.64 (Std Dev = 1.35). The KHOS-B scores were also divided into low and high behavioral involvement groups. The low and high information and behavioral involvement groups were used to analyze the results of the questionnaire completed by the 25 subjects. Accordingly, the results listed below are divided into high or low information seeking and high or low behavioral involvement.

A total of 9 subjects (36%) of the sample population were categorized as low information seeking and low behavioral involvement. Of the sample population, 3 subjects (12%) were categorized as high information-seeking and low behavioral involvement. Six subjects (24%) were identified as low information-seeking and high behavioral involvement. Finally, 7 subjects (28%) of the subjects were high information seeking and high behavioral involvement.

Triangulation and Measurement

The concept of methodological triangulation is associated with the use of more than one method for data gathering and measurement practices. As Webb et al (1966) stated: “Once a proposition has been confirmed by two or more independent measurement processes, the uncertainty of its interpretation is greatly reduced.[39] The most persuasive evidence results from a triangulation of measurement processes. To extend this concept, this project used Denzin’s 1970 definition of between method triangulation, which involves contrasting research methods, semi-structured interviews and questionnaire in the case of this study.[40] In this application, triangulation is taken to include the combined use of qualitative research and quantitative research to determine how far they arrive at convergent findings. [40] For the purpose of this study, the multi-method approach was used to increase the completeness of the findings as compared to if the study had leveraged one of the methods alone. This triangulation method was also used to check the validity of the findings by cross-checking them with another method.

Of the entire sample population, only three subjects had interviews and questionnaire results which did not exhibit positive correlation, limiting the ability to identify their information seeking and behavioral preferences with respect to healthcare decisions. Although “n” may be considered small for computing a quantitative questionnaire data and establishing reliability, the three subjects had one major factor in common: none of them had personal or second-hand experience with medical uncertainty. It is reasonable to interpret this as suggesting that past experience (with medical uncertainty) alone of will help with the consistency of predicting future behavioral intent to participate in shared decision-making in the event of an uncertain situation.

Trustworthiness of the study

The reliability of the study was also increased through a demonstrated link between the results and data. In addition to the use of triangulation, the credibility of the study was increased through planned regular debriefing sessions between the research coordinator and the two research assistances. To facilitate transferability and dependability, the research coordinator established clear description of the context, transparent selection criteria and characteristics of the participants, systematic data collection processes, and ongoing analysis documentation and archiving. [41]

Discussion

Throughout this study, the core category of “coping or dealing with uncertainty” emerged as a primary characteristic, connecting and convening the experiences of the subjects efforts to understand uncertainty. Despite having information and social support, the subjects still had to cope with the idea of uncertainty before determining how to proceed with regard to shared decision-making. The core category of coping was enhanced defined by the three descriptive categories described in the framework:1) representation of uncertainty, 2) coping 3) behavioral intent. This supports the literature that information-seeking has also been described as a model of coping, with coping being the link between information preference, desire for behavioral involvement, and information-seeking behavior in health related situations that involve risk. [42] Information-seeking can be used to support direct action and/or regulate emotions in a stressful situation, such as situations of uncertainty. [43] In the Krantz survey, where it was found that the level of preference is related to number of questions asked by patients in healthcare environments and also related to the general desire to be involved in health care decisions. Information is relayed to patients to guide appropriate coping. Knowledge of a patient’s preference for information is very important as the healthcare professional identifies the manner in which he/she should interact with the patient during a medical consultation. Therefore, appropriately matching preference level with the amount and depth of information can enhance patient outcomes.

Another theme that emerged from the study was the difference in information-seeking behavior when medical uncertainty was involved. Some patients responded to uncertainty by actively seeking information, whether from their physicians, internet, or family members. This behavior was observed as a way of coping with the concept of uncertainty.

In addition, this study identified a correlation between the manner in which a subject represents the idea of uncertainty in his mind and his/her behavioral intent towards decision-making in the situations of medical uncertainty. These results suggest that, because of an individual’s complex behavioral, cognitive and emotional responses to uncertainty, coping with the idea or representation of uncertainty has greater potential benefit than than simply helping an individual understand it. [44–46]

Another interesting concept identified through this research involves the presentation of certain information in situations of medical uncertainty. There does not appear to be a consensus among healthcare professionals regarding optimal methods for communicating and understanding different types of uncertainty. The manner in which information is communicated and presented in times of medical uncertainty can affect how the uncertain situation/condition is perceived and responded to by individuals. However, healthcare professionals still have limited information regarding optimal methods for applying mechanisms to achieve these framing effects. There are many ways to present uncertainty – verbally, statistically, graphically, etc. Tailoring information to the individual patient may increase the perceived relevance of situational information, thus providing easier access to information and increasing the likelihood of patient participation in decision-making processes.

Finally, although one might expect that trust and positive relationships with their physician would be associated with a high intent to participate in shared decision-making, subjects in this study felt that their intent to participate in SDM was more likely when they had less trust in their physician. This finding is consistent with Kraetschmer et al [47] and Fraenkel & McGraw[48] studies. This study adds to the findings that patients having high levels of trust may believe that their physicians understand their values and know already what are best for them.

Study limitations

Subjects were self-selected volunteers who responded to fliers. These people were likely to either have an interest or concern about medical decision-making and human behavior and therefore may have responded in varied, important, and unknown ways from other patients.

Conclusion

The research conducted by this study explored the fundamental understanding of how an individual processes, interprets, and responds to information regarding medical uncertainty and their behavioral intent to participate in decision-making. By administering a semi-structured interview to a subject population of 25 men, this objective of this study was to determine and understand behavioral intent to participate in shared decision-making in situations involving medical uncertainty. The content analysis of these interviews led to the development of category framework regarding the individual’s representation of medical uncertainty, and their behavioral intent to participate in medical decision-making. The results revealed three main categories including: 1) an individual’s representation of medical uncertainty, 2) how the individual copes with medical uncertainty, and 3) the individual’s behavioral intent to seek information and participate in shared decision-making during times of medically uncertain situations. This category framework helped highlight pathways and interactions between the variables identified through the content analysis of the data obtained through the semi-structured interviews. These pathways and interactions were observed to be consistent with previous research and literature relevant to the study of behavioral intent and decision-making. This framework should be incorporated in future studies in order to provide a comprehensive and systematic exploration of variables and processes associated with uncertainty and behavioral intent outcomes for shared decision-making. Finally, with future additional research, this framework has the potential to provide a basis for selectively testing and refining existing behavioral theories, improving their predictive potential with respect to decision-making in medically uncertain situations. Since the task of formulating such usage is cumulative and progressive, this study proposes the category framework as a first step towards further integration of individual representation, coping, and behavioral intent into the study and application of shared decision-making in medically uncertain situations.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Theory of Reasoned Action, Ajzen& Fishbein 1980

Figure 2.

Application Example of Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)

Figure 3.

Category Framework

Figure 4.

Triangulation Method

Table 1.

Interview Schedule

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Past medical history Past preventive behavior |

|---|---|

| Cognitive/Psych factors | Knowledge of screening, treatment, disease Perceived susceptibility to a disease Worry about having the disease Interest in knowing diagnostic status Belief in disease prevention & curability Belief in Salience and coherence of behavior Belief in efficacy to detection and treatment Concern about behavior-related discomfort |

| Social support and influence factors | Family member Friends Healthcare professionals Colleagues |

| Programmatic factors | Characteristics of healthcare delivery system |

| SDM Elements | Partnership Support Respect Information Compromise Mutual Agreement |

Table 2.

Subject Demographics

| African American n = 63 (%) |

Caucasian n = 38 (%) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Age | 16 (56.4) | 9 (58.2) | 57.1 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 2 (13) | 1 (11) | 3 |

| Married | 9 (56) | 6 (67) | 15 |

| Divorced | 3 (19) | 1 (11) | 4 |

| Widowed | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Civil Union | 1 (6) | 1 (11) | 2 |

| Education | |||

| Some High School | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| High School or GED | 8 (50) | 1 (11) | 9 |

| Post High School Training other than college (Vocational, technical, etc.) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 3 |

| Some College | 3 (19) | 5 (56) | 8 |

| College Graduate (Bachelor’s Degree) | 1 (6) | 3 (33) | 4 |

| Graduate Degree (Masters or Doctorate) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Health Issues* | |||

| Hypertension | 11 (69) | 5 (56) | 16 |

| COPD | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Heart Disease | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 2 |

| Diabetes | 8 (50) | 1 (11) | 9 |

| None | 2 (13) | 4 (33) | 6 |

Table 3.

KHOS results

| Behavioral Involvement | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Totals | ||||||||

| Information Seeking | Low | Population | Count | % of Total | Population | Count | % of Total | Population | Count | % of Total |

| Total Subjects | 9 | 36% | Total Subjects | 6 | 24% | Total Subjects | 15 | 60.00% | ||

| Black | 8 | 50% | Black | 1 | 6% | Black | 9 | 56.25% | ||

| White | 1 | 11% | White | 5 | 56% | White | 6 | 66.67% | ||

| High | Population | Count | % of Total | Population | Count | % of Total | Population | Count | % of Total | |

| Total Subjects | 3 | 12% | Total Subjects | 7 | 28% | Total Subjects | 10 | 40.00% | ||

| Black | 2 | 13% | Black | 5 | 20% | Black | 7 | 43.75% | ||

| White | 1 | 11% | White | 2 | 22% | White | 3 | 33.33% | ||

| Totals | Population | Count | % of Total | Population | Count | % of Total | Population | Count | ||

| Total Subjects | 12 | 48.00% | Total Subjects | 13 | 52.00% | Total Subjects | 25 | |||

| Black | 10 | 62.50% | Black | 6 | 37.50% | Black | 16 | |||

| White | 2 | 22.22% | White | 7 | 77.78% | White | 9 | |||

References

- 1.Murray E, et al. Clinical decision-making: physicians’ preferences and experiences. BMC Family Practice. 2007;8(10) doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf Steven H, Krist Alex. The Liability of Giving Patients a Choice: Shared Decision Making and Prostate Cancer. Am Family Phys. 2005;71(1871):1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brody DS, Miller SM, Lerman CE, Smith DG, Caputo GC. Patient perception of involvement in medical care: relationship to illness attitudes and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:506–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02599549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szolovits P. Uncertainty and Decisions in Medical Informatics. Methods of Information in Medicine. 1995;34:111–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh Amit K. Dealing with medically uncertainty: a physician’s perspective. Minnesota Medicine. 2004;87(10):48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gosh AK. Understanding medically uncertainty: a primer for physicians. Journal of the Association of physicians of India. 2004;52:739–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gosh AK. On the challenges of using evidence-based information: the role of clinical uncertainty. Journal of Laboratory & Clinical Medicine. 2004;144(2):60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Rye BJ. Understanding and promoting AIDS-preventive behavior: Insights from the theory of reasoned action. Health Psychology. 1995;14(3):255–64. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montano DE, Taplin SH. A test of an expanded theory of reasoned action to predict mammography participation. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32(6):733–41. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manstead AS, Proffitt C, Smart JJ. Predicting and understanding mother’s infant-feeding intentions and behavior: thesting the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44(4):657–71. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.44.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagozzi R, Baumgartner H, Yi Y. State versus Action Orientation and the Theory of Reasoned Action: An application to Coupon Usage. Journal of Consumer Research. 1992;18 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison DM, Gillmore MR, Baker SA. Determinants of Condom Use among High-risk heterosexual adults: a test of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2006;25(8):651–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brubaker RG, Wickersham D. Encouraging the practice of testicular self-examination: a field application the the theory of reasoned action. Health Psychology. 1990;9(2):154–63. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papatsoris A, Anagnostopoulos F. Prostate cancer screening behaviour. Public Health. 2009;123(1):69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross L, et al. Toward a Model of Prostate Cancer information seeking: Identifying salient behavioral and normative beliefs among african american men. Health Education & Behavior. 2007;34(3):422–40. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao L. Behavior informatics and analytics: let behavior talk. Workshop on Domain Driven Data Mining joint with 2008 International Conference on Data Mining; IEEE Computer Society Press; 2008. pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22:453–74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(Sheppard, Hartwick, & Warshaw, 1988, p. 325)

- 21.Légaré F, Godin G, Dodin S, Turcot-Lemay L, Laperrière L. Adherence to hormone replacement therapy: a longitudinal study using the theory of planned behaviour. Psychology and Health. 2003;18:351–371. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Légaré F, Godin G, Ringa V, Dodin S, Turcot L, Norton J. Variation in the psychosocial determinants of the intention to prescribe hormone therapy: a survey of GPs and gynaecologists in France and Quebec. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gagnon MP, Godin G, Gagne C, Fortin JP, Lamothe L, Reinharz D, Cloutier A. An adaptation of the theory of interpersonal behaviour to the study of telemedicine adoption by physicians. Int J Med Inf. 2003;71:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foy R, Bamford C, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Lecouturier J, Eccles M, Steen N, Grimshaw J. Which factors explain variation in intention to disclose a diagnosis of dementia? A theory-based survey of mental health professionals. Implement Sci. 2007;2:31. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao Longbing. In-depth behavior understand and use: The behavior informatics approach. Information Sciences. 2010;180:3067–3085. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimer BK, Glanz K. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2. National Cancer Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagozzi R, Baumgartner H, Yi Y. State versus Action Orientation and the Theory of Reasoned Action: An application to Coupon Usage. Journal of Consumer Research. 1992;18 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kukafka R, et al. Grounding a new information technology implementation framework in behavioral science: a systematic analysis of the literature on IT use. Jounal of Biomedical Informatics. 2003;36(218):227. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffres Leo W, et al. Communication as a predictor of willingness to donate one’s organs: an addition to the Theory of Reasoned Action. Progress in Transplantation. 2008;18(4):257–62. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fishbein Martin. A reasoned action approach to health promotion. Medical Decision Making. 2008;28(6):834–44. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08326092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krantz DS, Baum A, Windeman MV. Assessment of perferences for self-treatment and information in healthcare. J Person Soc Psychol. 1980;39(5):977–900. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsiesh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.schilling 2006

- 36.Miles M, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber RP. Basic Content Analysis. Sage publications; Newburry Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catanzaro M. Using qualitative analytical techniques. In: Woods P, Catanzaro M, editors. Nursing Research; Theory and Practice. C.V. Mosby Company; New York: 1988. pp. 437–456. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denzin NK. The Research Act in Sociology. Chicago: Aldine; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webb EJ, Campbell DT, Schwarts RD, Sechrest L. Unobtrusive Measures: Nonreactive measures in the social sciences. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing: concepts, procedures, and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss S. Information preferences and information-seeking in hospitalized surgery patients. In: Waltz CF, Strickland OL, editors. Measuremen of Nursing Outcomes. Vol. 1. New York: Springer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Politi MC, Han PK, Col NF. Medical Decision-Making, White Paper Series. 2007. Communication the Uncertainty of Harms and Benefits of Medical Interventions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babrow AS, Kline KN. From “reducing” to “coping with” uncertainty: reconceptualizing the central challenge in breat self-exams. Soci Sci Med. 2000;51(12):1805–16. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brashers DE. Communication and uncertainy management. J Commun. 2001;51(3):477–97. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB. How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision-making? Health Expect. 2004;7:317–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fraenkel L, McGraw S. What are the Essential Elements to Enable Patient Participation in Medical Decision Making? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):614–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.