Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Standardized instruments are needed to assess the activity of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), to provide endpoints for clinical trials and observational studies. We aimed to develop and validate a patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument and score, based on items that could account for variations in patients’ assessments of disease severity. We also evaluated relationships between patients’ assessment of disease severity and EoE-associated endoscopic, histologic, and laboratory findings.

METHODS

We collected information from 186 patients with EoE in Switzerland and the US (69.4% male; median age, 43 years) via surveys (n = 135), focus groups (n = 27), and semi-structured interviews (n = 24). Items were generated for the instruments to assess biologic activity based on physician input. Linear regression was used to quantify the extent to which variations in patient-reported disease characteristics could account for variations in patients’ assessment of EoE severity. The PRO instrument was prospectively used in 153 adult patients with EoE (72.5% male; median age, 38 years), and validated in an independent group of 120 patients with EoE (60.8% male; median age, 40.5 years).

RESULTS

Seven PRO factors that are used to assess characteristics of dysphagia, behavioral adaptations to living with dysphagia, and pain while swallowing accounted for 67% of the variation in patients’ assessment of disease severity. Based on statistical consideration and patient input, a 7-day recall period was selected. Highly active EoE, based on endoscopic and histologic findings, was associated with an increase in patient-assessed disease severity. In the validation study, the mean difference between patient assessment of EoE severity and PRO score was 0.13 (on a scale from 0 to 10).

CONCLUSIONS

We developed and validated an EoE scoring system based on 7 PRO items that assesses symptoms over a 7-day recall period. Clinicaltrials.gov number: NCT00939263.

Keywords: disease activity measurement, esophagus, patient reported outcome, marker

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a young disease, as only a little more than two decades have passed, since this condition has been recognized as its own standing entity.1,2 Some years ago, a panel of international experts defined EoE as “a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated, esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation”.3 The prevalence of EoE is currently estimated at 1/2,000 in the pediatric and adult population of the United States and Europe.4,5,6,7 Most adult patients suffer from dysphagia. However, patients may also report refractory heartburn and/or chest pain, which is centrally located and does not adequately respond to acid-suppressive medications.8,9,10

A standardized and validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument assessing symptom severity in patients with EoE is urgently needed to define meaningful endpoints for clinical trials and to follow disease evolution in observational studies. Until now, EoE symptoms in adult patients have been evaluated in clinical trials using different PRO instruments. For example, Alexander et al. used the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire 30-Day (MDQ-30) version and found that swallowed fluticasone improved histologic characteristics, but not symptoms of EoE in adult patients.11 The MDQ-30 version has been validated in a group of patients presenting with dysphagia and thoracic pain due to various gastrointestinal diseases, but not specifically due to EoE.12 An ad hoc-constructed symptom assessment instrument was used by Straumann et al. in a placebo controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of budesonide in adult EoE patients.13,14 Dellon et al. developed the dysphagia symptom questionnaire (DSQ), a 3-item electronic PRO administered daily to assess the frequency of dysphagia caused by eating solid food and relief strategies during the dysphagia episodes.15 This DSQ was evaluated in a group of 35 adolescent and adult EoE patients with clinically and histologically active disease.15 Of note, none of these three instruments fulfill all the criteria currently required for an EoE PRO instrument. The assessment of dysphagia is particularly challenging, as it depends not only on disease severity, but also on consistencies of foods consumed, and on behavioral adaptation strategies to living with dysphagia. Thus, any PRO instrument assessing dysphagia must take these factors into account.

Given the lack of standardized, validated PRO instruments, the results of clinical trials performed in EoE cannot be easily compared. This might also explain why different therapeutic trials document various degrees of association between patient-reported symptoms and endoscopic and histologic findings.11,13,14 The current situation poses a major challenge for regulatory approval of EoE therapies.16,17

In this paper, we describe the process of development and validation of a PRO instrument for adult EoE patients. The study was carried out in accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines.16

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study overview

The adult EEsAI study was carried out in three phases, which are illustrated in supplementary Figure 5. During the 1st phase, a comprehensive list of relevant items to be potentially incorporated into the PRO, endoscopy, histology, and blood biomarker instruments was generated. During the 2nd phase, the prototypes of standardized instruments were evaluated in a first patient group. Data derived from the PRO instrument were used to derive a symptom severity score. During the 3rd phase, the PRO instrument and PRO score were validated in a second group of adult EoE patients.

Item generation

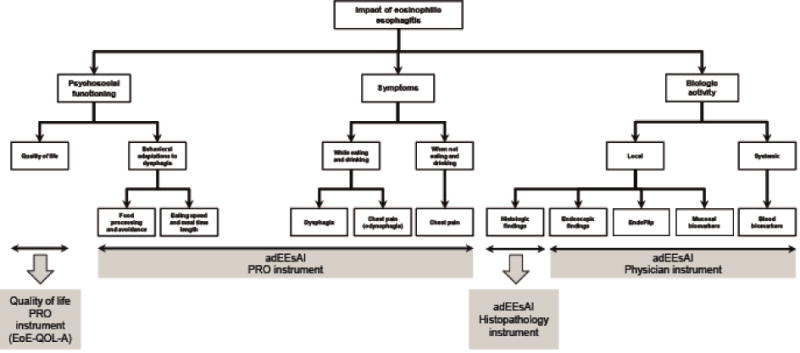

We first established a conceptual framework for instruments to assess symptoms, behavioral adaptations, and biologic activity of adult EoE patients (Figure 1). For the item generation, a review of the literature and the existing instruments to assess clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and biochemical EoE activity was carried out, and expert opinion was provided using the Delphi technique (telephone conferences and emails). The Delphi technique allows geographically dispersed experts to reach a consensus on a particular complex task.18 A Delphi group of adult EoE gastroenterologists (N = 9), allergists (N = 2), and pathologists (N = 2) from Switzerland and the United States contributed a list of items that they thought best in reflecting endoscopic [N = 6 items], histologic [N = 7 items], and biochemical activity [N = 5 items]).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for development of EEsAI instruments. The components of the flow chart outlined with a dashed line, such as EndoFlip or mucosal biomarkers, were not, as of yet, evaluated for the purposes of the EEsAI study.

Abbreviations: EndoFlip®, Endolumenal Functional Lumen Imaging Probe.

For the PRO instrument item generation, patient input was obtained by a mixed methods approach using open-ended patient symptom surveys (N = 135 patients), focus groups (N = 27 patients) as well as semistructured patient interviews (N = 24 patients). The qualitative methods of the development of the PRO instrument are described in detail in the supplementary section (Appendix 1 includes supplementary Tables 1 to 8 and supplementary Figures 1 to 4) according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines.19,20

Item reduction and formatting of the instruments assessing biologic activity

Delphi group members ranked each provided item assessing biologic EoE activity from 0 (not important) to 5 (very important). The number of items was then reduced by rank order from 7 to 5 items, and from 5 to 3 items for histology and blood biomarkers, respectively. The number of items (N = 6) for endoscopy did not change. The generated instruments were distributed to the Delphi group, and multiple Delphi rounds were conducted to minimize interobserver variability, establish clear definitions and to ensure that the final instruments reflect the consensus opinion.

PRO instrument

The EEsAI instruments were developed in such a way that PROs are assessed separately from items measuring biologic activity.21,22,23,24 The PRO instrument included items on symptom severity and behavioral adaptations, which were recalled over 24 hours, 7 days, and 30 days, to determine the optimal recall period.

The PRO instrument contained 5 domains: a general domain to assess sociodemographic characteristics, two symptom domains to address symptoms dependent and independent of food intake, a co-morbidities domain and a medication domain. The PRO instrument consisted of 45 items. The domain addressing symptoms while eating or drinking includes items on duration, frequency and severity of dysphagia, time required for meal intake, dysphagia upon consuming liquids, and pain when swallowing. The Visual Dysphagia Question (VDQ) addressed the severity of dysphagia when consuming food of 8 distinct consistencies. The 8 food consistencies and examples of foods to illustrate those consistencies were as follows: 1) solid meat (such as steak, chicken, turkey, lamb), 2) soft foods (such as pudding, jelly, apple sauce), 3) dry rice or sticky Asian rice, 4) ground meat (hamburger, meatloaf), 5) fresh white untoasted bread or similar foods (such as doughnut, muffin, cake), 6) grits, porridge (oatmeal), or rice pudding, 7) raw fibrous foods (such as apple, carrot, celery), and 8) French fries. The examples were chosen based on foods that are consumed in the United States, Europe, and Canada. The behavioral adaptations (avoidance, modification and slow eating [AMS] of various foods) were also assessed in the context of consuming 8 distinct food consistencies. A domain addressing symptoms independent of eating or drinking included items on chest pain, heartburn, and acid regurgitation. The last two items were reproduced from the MDQ-30 with the permission of the copyright owners.12

Patients were asked to provide a Patient Global Assessment (PatGA) of EoE severity on an 11-point Likert scale, where a score of 0 is defined as ‘no symptoms’ and a score of 10 is defined as ‘most severe symptoms’. The PatGA was used as a main outcome parameter for every recall period. The PRO instrument was first created in English. Translation of the PRO instrument into German and French was performed in accordance with the World Health Organization guidelines for translation and adaptation of instruments.25

Instruments assessing endoscopic, histologic, and laboratory findings

The instrument for physicians consisted of 5 domains: a general domain for physician and patient characteristics, a gastro-esophageal reflux (GERD) domain, an anti-eosinophil treatment domain, a blood biomarker domain, and an endoscopy domain. The instrument also incorporated the physician global assessment of EoE severity (PGA) item. The PGA took into account patients’ symptoms (based on history taking), endoscopic, histological, and biochemical findings. The PGA was assessed on an 11-point Likert scale, where a score of 0 was defined as ‘inactive EoE’ and a score of 10 was defined as ‘most active EoE’. The endoscopy domain of the physician instrument was designed based on the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS) classification and grading system.26

The histopathology instrument contained three domains: a general domain for pathologists and two domains assessing EoE-associated histologic features in the distal and proximal esophagus. ‘Distal’ was defined as section of the esophagus 5 cm above the gastroesophageal junction, while ‘proximal’ was defined as section spanning the top 1/2 of the esophagus.

The detailed overview of the physician and histopathology instruments can be found in supplementary Table 9.

Study population

The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00939263) and was approved by local institutional review boards and ethics committees. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Between April, 2011 and December, 2012 (evaluation group) and May, 2013, and July, 2014 (validation group), EoE patients were recruited in 1 ambulatory care clinic and 7 hospitals in Switzerland and the United States. Adult EoE patients (≥ 17 years of age) in need of an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for initial diagnosis, for confirming a suspected diagnosis, or for monitoring previously-diagnosed EoE were invited to participate in the study. Patients provided informed consent to participate in the study. EoE was diagnosed by investigators at all centers using published diagnostic criteria.3 EoE patients with concomitant GERD were also included if they were under a continued proton-pump inhibitor therapy at the time of EGD. All patients underwent a standardized physical examination by a physician. EGD was performed and at least 8 biopsies were obtained (4 from the proximal and 4 from the distal esophagus). Endoscopic findings were assessed according to the endoscopy atlas created by Hirano et al.26 Levels of blood eosinophils were also measured. Patients completed the PRO instrument before the EGD. Gastroenterologists completed the instrument for physicians, while pathologists completed the histopathology instrument.

Histologic evaluation was performed by the local center pathologist. Five-μm sections were cut from paraffin blocks and hematoxylin & eosin stained for examination by light microscopy. The area of a high power field and percentage of the area covered by tissue were noted to allow for calculation of peak eosinophil counts/mm2. To determine the peak eosinophil count, at least 5 levels of every esophageal biopsy specimen were surveyed under low power, and the eosinophils in the most densely infiltrated area were counted under high power examination.

Construction of the visual dysphagia question and avoidance, modification and slow eating scores

The data obtained from the VDQ and AMS items were used to create a composite score. A sample calculation of the VDQ and AMS scores is provided in Appendix 2.

Data handling and statistical analysis

Data were double-entered by two researchers into EpiData database (version 3.1, the EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) and imported into Stata (version 13, College Station, Texas, USA) for analysis. Descriptive results are presented as frequencies and corresponding percentages of the group total or median plus interquartile range (IQR). We used multivariable linear regression analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA) models to identify redundant information and to obtain an equation for constructing a PRO score. In these analyses, the PatGA was used as the outcome, and responses to specific items in the instrument as predictors. These analyses allowed us to quantify the extent to which included items explained the variability in PatGA. The variables included in the final models were chosen on the basis of their relative contribution to the explanatory power of the models, coherence of parameter estimates and expert opinion. We evaluated the fit of the models using the coefficient of determination (R2). To validate the EEsAI PRO instrument, a second group of adult EoE patients was included, and the EEsAI PRO score was calculated based on the regression coefficients. The R2 was calculated to assess the relationship between EEsAI PRO score and the PatGA. A Bland-Altman plot was used to evaluate the agreement between the calculated EEsAI PRO score and the PatGA.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

153 and 120 adult EoE patients were recruited for evaluation and validation phase, respectively. The characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Age at inclusion, sex, ethnicity, and education level were comparable between the two groups. When compared to the patients in the evaluation group, the patients in the validation group were more likely to have EoE symptom onset > 5 years before inclusion into the study (67.2% vs. 52.9%), to experience self-reported food allergies (50% vs. 30.1%) and to receive EoE-specific therapies in the last 12 months before inclusion into the study (85.8% vs. 58.8%); however, they were less likely to have concomitant GERD (15% vs. 30.7%) and be treated with proton-pump inhibitor therapy (32.5% vs. 55.6%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Evaluation group | Validation group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Frequency | % | Frequency | % |

| Number of patients | 153 | (100.0) | 120 | (100.0) |

| Males | 111 | (72.5) | 73 | (60.8) |

| Age at inclusion (median, IQR, range) | 38 | (29 – 46; 17 – 71) | 40.5 | (31 – 49; 19 – 80) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 148 | (96.7) | 114 | (95.0) |

| Non-white | 5 | (3.3) | 6 | (5.0) |

| Education | ||||

| Compulsory schooling | 2 | (1.3) | 1 | (0.8) |

| Vocational training | 38 | (24.8) | 33 | (27.5) |

| Upper secondary education | 67 | (43.8) | 54 | (45.0) |

| University education | 46 | (30.1) | 32 | (26.7) |

| EoE symptoms onset | ||||

| 1 to 3 months ago | 1 | (0.7) | 0 | (0.0) |

| 4 to 11 months ago | 8 | (5.2) | 2 | (1.7) |

| 1 to 5 years ago | 63 | (41.2) | 38 | (31.7) |

| more than 5 years ago | 81 | (52.9) | 80 | (66.6) |

| Allergic diseases / Allergies | ||||

| Asthma | 53 | (34.6) | 42 | (35.0) |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis | 92 | (60.1) | 72 | (60.0) |

| Eczema | 18 | (11.8) | 34 | (28.3) |

| Food allergy | 46 | (30.1) | 60 | (50.0) |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) | 47 | (30.7) | 18 | (15.0) |

| Diagnosis established | ||||

| Clinically | 28 | (59.6) | 3 | (16.7) |

| Endoscopically | 11 | (23.4) | 6 | (33.3) |

| Based on pH-metric studies | 1 | (2.1) | 2 | (11.1) |

| Clinically and endoscopically | 7 | (14.9) | 5 | (27.8) |

| Concomitant medications | ||||

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 85 | (55.6) | 39 | (32.5) |

| Histamine antagonists (H2-receptor) | 7 | (4.6) | 1 | (0.8) |

| Histamine antagonists (H1-receptor) | 25 | (16.3) | 18 | (15.0) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma | 4 | (2.6) | 4 | (3.3) |

| β2-adrenergic agonists for asthma | 20 | (13.1) | 2 | (1.7) |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists for asthma | 4 | (2.6) | 1 | (0.8) |

| EoE-specific treatments in the last 12 months | 90 | (58.8) | 103 | (85.8) |

| Hypo-allergenic diets | 20 | (13.1) | 19 | (15.8) |

| Swallowed topical corticosteroids | 65 | (42.5) | 78 | (65.0) |

| Esophageal dilation | 30 | (19.6) | 26 | (21.7) |

Predominant EoE symptoms (evaluation group)

Table 2 illustrates the predominant symptoms of patients in the evaluation group, reported over the past 24 hours, 7 days and 30 days. When recalled over the last 24 hours, 7 days, and 30 days, the median PatGA assessed on the 11-point Likert scale (range 0 – 10) was 1 (IQR 0 – 3), 2 (IQR 1 – 4) and 2 (IQR 1 – 4), respectively. Forty-one (27.5%), 91 (59.5%), and 126 (82.4%) patients reported trouble swallowing in the past 24 hours, 7 days and 30 days, respectively. Overall, except for the meal duration, which remained relatively constant over the time periods examined, patients were more likely to experience dysphagia and pain events with increasing length of the recall period.

Table 2.

Type and frequency of EoE-related symptoms assessed in the EEsAI PRO instrument over 3 recall periods (N = 153).

| Recall period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Characteristic | 24 hours | 7 days | 30 days | ||||||

| Median symptom severity (IQR; range) | 1 | (0 – 3; 0 – 10) | 2 | (1 – 4; 0 – 10) | 2 | (1 – 4; 0 – 10) | |||

| Frequency of trouble swallowing | |||||||||

| Never | 111 | (72.5) | Never | 62 | (40.5) | Never | 27 | (17.6) | |

| 1 to 3 times / day | 34 | (22.2) | 1 to 3 times / week | 60 | (39.2) | 1 to 3 times / month | 40 | (26.1) | |

| ≥ 4 times / day | 7 | (4.6) | 4 to 6 times / week | 15 | (9.8) | 1 to 3 times / week | 52 | (34.0) | |

| – | – | – | – | 4 to 6 times / week | 19 | (12.4) | |||

| – | – | Daily | 16 | (10.5) | Daily | 15 | (9.8) | ||

| Not applicable | 1 | (0.7) | – | – | – | – | |||

| Intensity of trouble swallowing | |||||||||

| Everything was easy to swallow | 111 | (72.5) | 53 | (34.6) | 26 | (17.0) | |||

| Slight retching | 22 | (14.4) | 69 | (45.1) | 73 | (47.7) | |||

| Food stuck for ≤ 5 minutes | 7 | (4.6) | 25 | (16.3) | 37 | (24.2) | |||

| Food stuck for > 5 minutes | 3 | (2.0) | 4 | (2.6) | 10 | (6.5) | |||

| Impacted food had to be removed | 6 | (3.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (2.0) | |||

| Missing | 4 | (2.6) | 2 | (1.3) | 4 | (2.6) | |||

| Duration of trouble swallowing | |||||||||

| No troubles swallowing | 107 | (69.9) | 56 | (36.6) | 26 | (17.0) | |||

| < 15 seconds | 24 | (15.7) | 45 | (29.4) | 49 | (32.0) | |||

| 16 to 59 seconds | 8 | (5.2) | 29 | (19.0) | 34 | (22.2) | |||

| 1 to 5 minutes | 3 | (2.0) | 18 | (11.8) | 28 | (18.3) | |||

| > 5 minutes | 10 | (6.5) | 5 | (3.3) | 16 | (10.5) | |||

| Not applicable | 1 | (0.7) | – | – | – | – | |||

| Time required to eat a regular meal | |||||||||

| < 15 minutes | 24 | (15.7) | 22 | (14.4) | 20 | (13.1) | |||

| 16 to 30 minutes | 91 | (59.5) | 88 | (57.5) | 86 | (56.2) | |||

| 31 to 45 minutes | 30 | (19.6) | 34 | (22.2) | 37 | (24.2) | |||

| 46 to 60 minutes | 3 | (2.0) | 3 | (2.0) | 3 | (2.0) | |||

| > 1 hour or refusal to eat | 3 | (2.0) | 4 | (2.6) | 5 | (3.3) | |||

| Not applicable | 2 | (1.3) | 2 | (1.3) | 2 | (1.3) | |||

| Frequency of pain when swallowing | |||||||||

| Never | 137 | (89.5) | Never | 122 | (79.7) | Never | 106 | (69.3) | |

| 1 to 3 times / day | 14 | (9.2) | 1 to 3 times / week | 21 | (13.7) | 1 to 3 times / month | 19 | (12.4) | |

| 4 or more times / day | 2 | (1.3) | 4 to 6 times / week | 6 | (3.9) | 1 to 3 times / week | 16 | (10.5) | |

| – | – | – | – | 4 to 6 times / week | 9 | (5.9) | |||

| – | – | Daily | 3 | (2.0) | Daily | 2 | (1.3) | ||

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | Missing | 1 | (0.7) | Missing | 1 | (0.7) | |

Assessing dysphagia severity and behavioral adaptations when ingesting foods of different consistencies

The symptoms of patients in the evaluation group were analyzed for a 24-hour, 7-day and 30-day recall period. The data of the VDQ and AMS recalled over a 7-day recall period are shown in supplementary Table 10. Generally, the severity of perceived dysphagia increased with increasing food consistency. For instance, 21 (13.7%) patients reported that they expected to experience severe difficulties when eating solid meat, and 11 (7.2%) patients reported the same when eating foods included in a ‘Raw foods’ category. In contrast, 5 (3.3%) and 6 (3.9%) patients reported that they expected to experience severe difficulties when consuming foods of the ‘Soft foods’ and ‘Grits and porridge’ categories, respectively. Increased time required to eat a certain food item was the most common complaint for EoE patients. For example, 103 (67.3%) patients experienced this phenomenon when eating solid meat, followed by 65 (42.5%) when eating ground meat, and 54 (35.3%) when eating bread. Food avoidance and food modification were less frequently reported for ‘soft foods’ and were mostly associated with high consistency foods, such as meat, and ‘Raw foods’, such as vegetables. Similar trends were observed, when data for the 24-hour and 30-day recall periods were analyzed (data not shown).

Choosing the appropriate symptom recall period: patient input

Patients participating in the focus groups (n = 27) were asked to choose the best time period to reliably recall their symptoms. The majority of patients indicated that 7 day-period is the best recall period (19/27, 70.4%), followed by 14-day (5/27, 18.5%), 30-day (2/27, 7.4%), and 24- hour (1/27, 3.7%) periods.

Development of the PRO score

We modeled the PatGA recalled over 24-hour, 7-day and 30-day periods by evaluating its strength and significance of association with the items of the PRO instrument. The following seven items were chosen for inclusion in the PRO instrument based on their contribution to the explanatory power of the models, coherence of parameter estimates and expert opinion: frequency of trouble swallowing, duration of trouble swallowing, pain when swallowing, VDQ, as well as 3 AMS questions. As the answers to VDQ and 3 AMS items were scored to derive VDQ and AMS scores, respectively, the resulting 5 variables were used for the purposes of analyses presented below.

Frequency of trouble swallowing, duration of trouble swallowing, severity of pain when swallowing, VDQ and AMS scores positively correlated with the PatGA for three recall periods. The data for the 7-day recall period are shown in supplementary Figure 6. We used multivariable linear regression analysis and ANOVA models to evaluate the contribution of chosen PRO variables to the PatGA. The results of these analyses are depicted in Table 3. In general, the increasing severity of PRO variables mostly showed a positive and significant relationship with the PatGA for three recall periods examined. For example, for the 7-day recall period, if a patient experienced daily episodes of trouble swallowing, the predicted PatGA increased by 2.61, when compared to 1.3 and 2.29 for trouble swallowing episodes experienced 1 – 3 and 4 – 6 times/week, respectively. If, in addition, the duration of those trouble swallowing episodes was > 5 minutes, the predicted PatGA increased by another 0.53.

Table 3.

Linear regression coefficients, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values for the models of Patient Global Assessment of the EoE activity (PatGA) recalled over the 24 hours, 7-days and 30-day periods.

| Recall period | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | 7 days | 30 days | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Characteristic | Coefa | 95% CI | P | Coefa | 95 % CI | P | Coefa | 95 % CI | P | ||

| Frequency of trouble swallowing | 0.01 | < 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Never | ref. | ref. | Never | ref. | ref. | Never | ref. | ref. | |||

| 1 – 3 times / day | 1.30 | (0.50 – 2.09) | – | – | – | 1 – 3 times / month | 0.31 | (−0.62 – 1.23) | |||

| ≥4 times / day | 0.86 | (−0.91 – 2.63) | 1 – 3 times / week | 1.30 | (0.74 – 1.86) | 1 – 3 times / week | 1.28 | (0.26 – 2.29) | |||

| – | – | – | – | 4 – 6 times / week | 2.29 | (1.40 – 3.18) | 4 – 6 times / week | 2.49 | (1.26 – 3.73) | ||

| – | – | – | – | Daily | 2.61 | (1.66 – 3.56) | Daily | 2.46 | (1.09 – 3.83) | ||

| Duration of trouble swallowing | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.52 | ||||||||

| ≤ 5 minutes | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | |||||

| >5 minutes | 1.64 | (0.16 – 3.13) | 0.53 | (−0.76 – 1.83) | 0.30 | (−0.61 – 1.20) | |||||

| Pain when swallowing | 0.10 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | |||||

| Yes | 0.78 | (−0.16 – 1.73) | 1.27 | (0.66 – 1.87) | 1.17 | (0.58 – 1.75) | |||||

| VDQ score | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| 0 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | |||||

| 0.1 – 2.5 | 0.14 | (−0.66 – 0.93) | 1.02 | (0.22 – 1.81) | 0.40 | (−0.60 – 1.39) | |||||

| 2.6 – 5.0 | 2.00 | (1.02 – 2.98) | 1.63 | (0.69 – 2.56) | 1.64 | (0.50 – 2.78) | |||||

| 5.1 – 7.5 | 3.22 | (1.66 – 4.78) | 1.81 | (0.43 – 3.20) | 1.62 | (−0.05 – 3.29) | |||||

| 7.6 – 10.0 | 6.19 | (4.21 – 8.17) | 1.96 | (0.45 – 3.47) | 1.57 | (−0.23 – 3.37) | |||||

| AMS score | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.10 | ||||||||

| 0 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | |||||

| 0.1 – 2.5 | −0.04 | (−0.73 – 0.66) | −0.57 | (−1.24 – 0.10) | −0.35 | (−1.13 – 0.43) | |||||

| 2.6 – 5.0 | −0.16 | (−1.16 – 0.85) | −0.06 | (−0.98 – 0.86) | −0.42 | (−1.43 – 0.59) | |||||

| 5.1 – 7.5 | 0.20 | (−1.34 – 1.73) | 0.77 | (−0.59 – 2.12) | 0.39 | (−1.15 – 1.93) | |||||

| 7.6 – 10.0 | 2.19 | (0.28 – 4.10) | 2.15 | (0.46 – 3.84) | 1.91 | (0.01 – 3.81) | |||||

| Constantb | 0.39 | (−0.21 – 0.98) | 0.20 | 0.38 | (−0.14 – 0.89) | 0.15 | 0.88 | (0.20 – 1.55) | 0.01 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| R2c | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.58 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: Coef, coefficient; CI, confidence interval; VDQ, visual dysphagia question; AMS, avoidance, modification and slow eating.

The coefficient represents the change in the value of the predicted PatGA for each category change of the independent variable. For example, for a 7 day recall period, the predicted PatGA increased by 1.3 if the patient reported having frequency of trouble swallowing of 1 – 3 times a week (category ‘never’ was the reference category). Similarly, the predicted PatGA increased by 2.29 and 2.61 points, if instead of not having any trouble swallowing (never), the patient reported having frequency of trouble swallowing of 4 – 6 times/week and daily, respectively. In this analysis, with frequency of trouble swallowing, duration of trouble swallowing etc. as independent variables and predicted PatGA as the dependent variable, the adjusted regression coefficient for duration of trouble swallowing represents the amount of variation in predicted PatGA that is due to the effects of duration of trouble swallowing alone, after frequency of trouble swallowing has been taken into account. For example, for a 7 day recall period, if the patient experienced daily episodes of trouble swallowing (with predicted PatGA increase of 2.61 points), his/her predicted PatGA increased by another 0.53 points, if the duration of those trouble swallowing episodes was > 5 minutes.

The constant represents the value of the predicted PatGA when all 5 values of independent variables are zero.

The coefficient of determination, R2, is a measure of the extent to which the regression model describes the observed data. The closer the R2 is to 1, the more precise the regression model is. Since R2 can be made artificially high by including a large number of independent variables that have an apparent effect purely by chance, only independent variables that have a large effect have been included in the model. This was also done to ensure that the statistical model is clinically meaningful and can be easily interpreted.

Although the contribution of 5 PRO variables to the PatGA was similar, when the 7-day and 30-day recall periods were examined, the contribution of these variables was quite different, when the 24-hour recall period was evaluated. For instance, for patients with a highest VDQ score quartile (score ranging from 7.6 to 10 – patients experiencing severe difficulties eating various foods), the predicted PatGA increased 6.19 for a 24-hour recall period, when compared to the increase of only 1.96 and 1.57 for the 7-day and 30-day recall periods, respectively. As such, for a 24-hour recall period, the VDQ score contributed ~ 3 – 4 times more to the predicted PatGA, when compared to the same VDQ score for the 7-day and 30-day recall periods. On the other hand, the coefficients for the highest values of the AMS score were quite similar with 2.19 for the 24-hour, 2.15 for the 7-day, and 1.91 for the 30-day periods.

The regression model with 5 variables of the EEsAI PRO instrument explained 72% (R2 = 0.72), 67% and 58% of the variability in PatGA for the 24-hour, 7-day and 30-day recall periods, respectively. Since R2 can be made artificially high by including a large number of independent variables that have an apparent effect purely by chance, only 5 independent variables that had a large effect were included into the model. Since the EEsAI PRO score for a 24-hour recall period was strongly influenced by a response to the VDQ, and the frequency of the events, such as pain and dysphagia, was also the lowest for the 24-hour recall period, we judged the 24-hour recall period to be less reliable for assessing EoE severity. Based on these statistical considerations and patient input, we concluded that a 7-day recall period represents the best choice for assessing patient-reported EoE severity by the means of the EEsAI PRO score.

Relationship between patient-assessed EoE severity and biologic EoE activity

We observed a positive association between endoscopic/histologic alterations and PatGA, which is illustrated by means of box plots in Figure 2. We did not find a correlation between PatGA and peripheral blood eosinophil counts (r = 0.045, P = 0.67).

Figure 2.

The relationship between endoscopic / histologic activity and patient-assessed EoE severity. The box contains the 25th – 75th percentile of values, the horizontal line in the middle of the box represents the median.

Validation of the score as well as practicability and content validity of the instrument

To validate the PRO score obtained during the evaluation phase, we calculated it for every EoE patient recruited in the validation group and compared it with the PatGA. The plot in Figure 3A shows that the EEsAI PRO score for the 7-day recall period predicted 65% of the variability in PatGA, which closely compares with the 67% of variability in PatGA explained by the EEsAI PRO score in the evaluation group. The Bland-Altman plot (Figure 3B) evaluates the agreement between the calculated EEsAI PRO score and the PatGA. A mean difference of only 0.13 between PatGA and EEsAI PRO score was observed. The upper and lower 95% limits of agreement were 3.04 and −2.79, respectively. Two versions of the validated 7-day EEsAI PRO score are shown in Table 4: 1) the original PRO score that ranges from 0 to 8.52 and the 2) ‘user-friendly’ EEsAI PRO score that ranges from 0 to 100.

Figure 3.

A. The correlation plot between the EEsAI PRO score and the PatGA in the validation group. B. The Bland-Altman plot for the agreement between the EEsAI PRO score and the PatGA in the validation group. The grey box indicates the 95 % limits of agreement.

Abbreviation: PatGA, patient global assessment; EEsAI, eosinophilic esophagitis activity index; PRO, patient-reported outcome.

Table 4.

EEsAI PRO score for the 7-day recall period. The score based on regression coefficients that ranges from 0 to 8.52 is shown in column 1. For clinical ease of use, a total of the score based on the regression coefficients was set to 100 and values for each category adjusted accordingly. This score is shown in column 2.

| Item | Score (based on regression coefficients) | Score (total set to 100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of trouble swallowing | Never | 0 | 0 |

| 1–3 times/week | 1.30 | 15 | |

| 4–6 times/week | 2.29 | 27 | |

| Daily | 2.61 | 31 | |

| Duration of trouble swallowing | ≤5 minutes | 0 | 0 |

| >5 minutes | 0.53 | 6 | |

| Pain when swallowing | No | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 1.27 | 15 | |

| VDQ score | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.1–2.5 | 1.02 | 12 | |

| 2.6–5.0 | 1.63 | 19 | |

| 5.1–7.5 | 1.81 | 21 | |

| 7.6–10.0 | 1.96 | 23 | |

| AMS score | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.1–2.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2.6–5.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5.1–7.5 | 0.77 | 9 | |

| 7.6–10.0 | 2.15 | 25 | |

|

| |||

| Total | 8.52 | 100 | |

Abbreviations: VDQ, visual dysphagia question; AMS, avoidance, modification, and slow eating score.

To evaluate the practicability and content validity of the validated EEsAI PRO instrument, we again contacted the 27 patients that participated in the focus groups. First, we evaluated the time patients needed to complete the EEsAI PRO instrument. When completing the instrument for the first time, patients required a median of 8 min (IQR 7 – 9 minutes, range 4 – 10 min). When asked “How difficult was it for you to complete this questionnaire?”, patients responded with a median of 1 (IQR 0 – 2, range 0 – 6; 11-point Likert scale where 0 stands for ‘no difficulties at all’, 10 stands for ‘very difficult’). To evaluate content validity, patients were asked the Likert scale question: “Does this questionnaire measure the complaints you have had / you currently have due to EoE?” Patents responded with a median of 8 (IQR 7 – 9, range 4 – 10; 10 stands for ‘perfectly’, 0 stands for ‘not at all’).

DISCUSSION

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a young disease, and, so far, no validated PRO instruments reliably assessing disease activity have been approved by regulatory authorities in US and Europe.

In this article, we describe the process of development and validation of the adult EEsAI PRO instrument that assesses EoE symptom severity. We developed the EEsAI PRO instrument according to FDA guidelines.16 Patient surveys, focus groups, and semistructured interviews were used to gain patient input to inform PRO instrument development. The resulting PRO instrument was evaluated in the first group of adult EoE patients. As gold-standard, we used patient assessment of disease severity (PatGA) to develop the EEsAI PRO instrument score. Based on statistical considerations and expert input, seven PRO items were selected. These items explained 67% of the total variability in the PatGA over a 7 day recall period. The EEsAI PRO instrument was validated in a second group of patients, and these seven items explained 65% of the variability in PatGA.

Assessment of dysphagia is a challenge, because this symptom depends not only on the severity of the disease, but also on the consistency of the ingested foods. Moreover, patients suffering from dysphagia rapidly develop behavioral adaptation strategies. The EEsAI PRO instrument assesses dysphagia caused by eating foods of different consistencies (VDQ) and takes into account behavioral adaptation strategies. The food consistencies of the VDQ are well-defined, and the foods used to illustrate those consistencies are frequently eaten in Western countries. As the VDQ includes items on various food groups, the EEsAI PRO instrument can be used to assess dysphagia in individuals with, among others, vegetarian dietary patterns, food intolerances, and in patients on elimination diets. Based on patient input, the EEsAI PRO instrument is a content-valid measure of EoE symptom severity and easy to complete.

PRO must be assessed in a defined recall period, but its choice depends on the following factors: 1) intended use of the instrument (conceptual framework), 2) the ability of the patient to remember the required information, 3) the extent to which the patient with a certain illness is burdened when completing the instrument, 4) the nature of the disease and the symptoms, and 5) the study design.27 The choice of a short recall period may lead to underestimation of symptom severity, when symptoms have a day-to-day fluctuation, or else may place undue burden on the patient, if patients are too ill to frequently complete the questionnaire. However, a long recall period may over- or underestimate the true health status of the patient. Based on patient preferences and statistical considerations presented in this study, the 7-day symptom recall period appears to be most suitable for this chronic condition.

In the recent years, several PRO instruments have been developed to assess EoE symptom severity. The Straumann Dysphagia Index does not assess dysphagia caused by eating food of different consistencies and does not take into account behavioral adaptations to living with dysphagia.13,14 The MDQ-30 Day version assesses dysphagia due to various esophageal diseases, but it has not been developed for EoE specifically.11,12 Using the DSQ, Dellon et al. recently evaluated dysphagia to solid food in a group of 35 adolescent and adult EoE patients.15 However, the term ‘solid food’ was not defined in the manuscript. In our study, we noted important differences in dysphagia severity and behavioral adaptations to dysphagia when patients consumed ‘solid food’ of different consistencies. For example, 75% of patients expected to experience dysphagia due to consumption of solid meat, whereas only 17% of patients expected to experience dysphagia when eating grits or porridge. Standardizing the assessment of dysphagia by ingestion of a defined test meal is one way of avoiding the complexities associated with the definition of ‘solid food’. However, such an approach may not be entirely practical and may raise ethical concerns associated with the exposure of the patients to the risk of food bolus impactions.28 The VDQ can be thought of as a ‘hypothetical test meal’ that potentially avoids the ethical issues associated with the ingestion of a defined test meal. In contrast to findings reported by Dellon et al.15, we found that patients frequently reported behavioral adaptations to dysphagia, such as food modification, food avoidance, and slow eating. For example, 67% of EoE patients reported eating solid meat slower than other people eating this type of food. We conclude that the EEsAI PRO instrument is the first to assess dysphagia caused by eating foods of distinct consistencies and also takes into account behavioral adaptations.

We observed a positive relationship between endoscopic and histologic alterations and patient-assessed EoE severity. We suspect that patients are to a lesser extent sensitive to mild endoscopic/histologic alterations when compared to moderate/severe ones. This relative lack of sensitivity to mild EoE alterations may explain why the positive correlations between EoE symptom severity and endoscopic and histologic findings have been documented in some,13,14,29 but not other studies11,30 in both adult and pediatric patients. The observed inconsistencies in the correlations between PRO and biologic items may also be related to the fact that dysphagia and behavioral adaptations in these studies has not been assessed in the context of the various food consistencies. Lastly, the assessment of endoscopic and histologic alterations in adult EoE has not been standardized in these studies. The recent work by Hirano et al. represents an important milestone in standardizing the assessment of endoscopic alterations in EoE.26 At present, the presumed pathophysiological mechanisms leading to EoE symptoms involve mucosal inflammation that is associated with dysmotility and/or mechanical restriction due to subepithelial fibrosis. We have yet to assess the relationship between symptom severity as captured by the EEsAI PRO instrument and the esophageal compliance that can be measured by the Endolumenal Functional Lumen Imaging Probe (EndoFLIP).31,32 For the purposes of clinical trials, it seems prudent to include both PRO and biologic endpoints as untreated eosinophil-predominant esophageal inflammation is associated with the generation of esophageal strictures that ultimately lead to symptoms.31,33

Our study has several strengths, but some limitations as well. We present data of the first international multicenter study to develop and validate an activity index for adult EoE patients. We followed the recommendations of the FDA for PRO instrument development.16 While the DSQ applies a scoring algorithm that involves giving a discrete arbitrarily-chosen value to each item response,15 the scores for individual items of the EEsAI PRO instrument are based on the regression coefficients of the linear regression modeling using PatGA (the current ‘gold-standard’ for patient-perceived symptom severity) as the outcome. The EEsAI PRO instrument is the first EoE-specific instrument designed to assess dysphagia caused by eating 8 different food consistencies and behavioral adaptations to living with dysphagia. As such, the validated EEsAI PRO instrument can be used to measure EoE symptom severity in patients that do not eat certain food categories, such as vegetarians or patients on specific elimination diets. The EEsAI PRO instrument is validated, content-valid, and easy to complete.

As for limitations, the EEsAI PRO instrument was evaluated and validated for adult patients only (≥ 17 years of age). The EEsAI PRO instrument is about to be used in an upcoming randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials that will provide data on the responsiveness. We also evaluated and validated the PRO instrument for a 24-hour recall period, in case completion of the PRO instrument on daily basis might be preferred in certain studies. These data will be published elsewhere. The development of an electronic PRO (hand-held device) will certainly make the instrument even more ‘user-friendly’.

In summary, we report on the development and validation of the adult EEsAI PRO instrument to assess EoE symptom severity over a 7-day recall period. The EEsAI PRO instrument is content-valid and is easy to complete. The development and validation of an instrument for standardized assessment of EoE symptom severity is a matter of paramount importance for guiding clinical decision making and for defining the outcome parameters for clinical trials as well as epidemiologic studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following members of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Maryland, USA, Office of New Drugs including Division of Gastroenterology and Inborn Errors Products, for their guidance to develop the PRO instrument: Andrew E. Mulberg, MD, and Robert Fiorentino, MD; Office of New Drugs, Rare Diseases: Anne R. Pariser, MD, MPH, and the Study Endpoints and Labeling Division: Elektra J. Papadopoulos MD, MPH, and Laurie B. Burke, RPh, MPH. The authors would like to also acknowledge the following researchers for their help with the qualitative work: Katrin Meier, MSc, Psychiatric University Hospital Basel, Switzerland; Brenda Spencer, PhD, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Lausanne, Switzerland; Karoly Kulich, PhD, Novartis, AG, Switzerland.

Grant support: This work was supported by the following grants to AMS, AS, CK and MZ: from Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 32003B_135665/1), AstraZeneca AG, Switzerland, Aptalis, Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline AG, Nestlé S. A., Switzerland, Receptos, Inc., and The International Gastrointestinal Eosinophil ResearcherS (TIGERS). Work of GTF was supported by a grant from National Institute of Health (grant number 1K24DK100303).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AMS score

avoidance, modification and slow eating score

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- DSQ

dysphagia symptom questionnaire

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- EEsAI

eosinophilic esophagitis activity index

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- EndoFLIP®

Endolumenal Functional Lumen Imaging Probe

- EREFS

EoE Endoscopic Reference Score

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- GERD

gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- IQR

interquartile range

- MDQ-30

Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire 30-Day

- PatGA

patient global assessment

- PGA

physician global assessment

- PRO

patient-reported outcome

- TS

trouble swallowing

- VDQ

visual dysphagia question

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Alain M. Schoepfer received consulting fees and/or speaker fees and/or research grants from AstraZeneca, AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Dr. Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, Nestlé S. A., Switzerland, and Novartis, AG, Switzerland. Alex Straumann received consulting fees and/or speaker fees and/or research grants from Actelion, AG, Switzerland, AstraZeneca, AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Dr. Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, Nestlé S. A., Switzerland, Novartis, AG, Switzerland, Pfizer, AG, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Radoslaw Panczak received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma Inc. Michael Coslovsky has has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Claudia E. Kuehni received research grants from AstraZeneca, AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Dr. Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, and Nestlé S. A., Switzerland. Yvonne Romero collaborates on projects supported by Aptalis Pharma, Inc. and Meritage Pharma, Inc. and receives royalties for commercial use of the MDQ-30. Elisabeth Maurer has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Nadine A. Haas has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Ikuo Hirano received research grants from Meritage Pharma, Inc., and consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Meritage Pharma, Inc., and Receptos, Inc. Jeffrey A. Alexander received research grants and/or consulting fees from Merck & Co., Inc., Meritage Pharma, Inc., and Aptalis Pharma, Inc. and receives royalties for commercial use of the MDQ-30. He also has financial interest in Meritage Pharma, Inc. Nirmala Gonsalves has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Glenn T. Furuta received consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc., Meritage Pharma, Inc., Knopp and Biosciences, LLC, and royalties from UpToDate, Inc. He is also a founder of EnteroTrack, LLC. Evan S. Dellon received research grants from AstraZeneca, AG, and Meritage Pharma, Inc. He has received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Novartis, AG, Receptos, Inc., and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. John Leung received research grants from Meritage Pharma, Inc. Margaret H. Collins received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Biogen Idec, Meritage Pharma, Inc., Novartis, AG, and Receptos, Inc. Christian Bussmann has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Peter Netzer has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Sandeep K. Gupta received consulting fees and/or speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories, Nestlé S. A., QOL, Receptos, Inc., and Meritage Pharma, Inc. Seema S. Aceves is a co-inventor of oral viscous budesonide (OVB, patent held by UCSD). She also received royalties for OVB from Meritage Pharma, Inc., and owns stocks in Meritage Pharma, Inc. She received consulting fees from Receptos, Inc., and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Mirna Chehade has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Fouad J. Moawad has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Felicity T. Enders receives royalties for commercial use of the MDQ-30. Kathleen J. Yost has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Tiffany H. Taft has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Emily Kern has no relevant financial, professional or personal relationships to disclose. Marcel Zwahlen received research grants from AstraZeneca, AG Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc., Dr. Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, and Nestlé S. A., Switzerland. Ekaterina Safroneeva received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc., and Novartis, AG, Switzerland.

Writing assistance: none.

Specific author contributions: Study concept and design – 1, acquisition of data – 2; analysis and interpretation of data – 3; drafting of the manuscript – 4; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content – 5; statistical analysis – 6; obtained funding – 7; administrative, technical, or material support – 8; study supervision – 9.

Alain M. Schoepfer 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9; Alex Straumann 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9; Radoslaw Panczak 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; Michael Coslovsky 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; Claudia E. Kuehni 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9; Elisabeth Maurer 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8; Nadine A. Haas 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; Yvonne Romero 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7; Ikuo Hirano 1, 2, 3, 5; Jeffrey A. Alexander 1, 2, 3, 5; Nirmala Gonsalves 1, 2, 3, 5; Glenn T. Furuta 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8; Evan S. Dellon 1, 2, 3, 5; John Leung 1, 2, 3, 5; Margaret H. Collins 1, 2, 3, 5, 8; Christian Bussmann 1, 2, 3, 5; Peter Netzer 1, 2, 3, 5; Sandeep K. Gupta 1, 2, 3, 5; Seema S. Aceves 1, 2, 3, 5; Mirna Chehade 1, 2, 3, 5; Fouad J. Moawad 1, 2, 3, 5; Felicity T. Enders 1, 3, 5, 6; Kathleen J. Jost 1, 3, 5, 6; Tiffany H. Taft: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6; Emily Kern: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6; Marcel Zwahlen 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9; Ekaterina Safroneeva 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8.

Please contact Alain M. Schoepfer for inquiries about permission to use the EEsAI instruments in a study.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authors

References

- 1.Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, Demeester TR, et al. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. A distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Dig Dig Sci. 1993;38:109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF01296781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Bernoulli R, et al. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis: a frequently overlooked disease with typical clinical aspects and discrete endoscopic findings. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1994;20:1419–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–306. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–941. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, et al. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1660–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straumann A, Rossi L, Simon HU, et al. Fragility of the esophageal mucosa: a pathognomonic endoscopic sign of primary eosinophilic esophagitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:407–412. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grudell AB, Alexander JA, Enders FB, et al. Validation of the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:202–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellon ES, Irani AM, Hill MR, et al. Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmcol Ther. 2013;38:634–642. doi: 10.1111/apt.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. Available at: www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed December 3rd, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Fiorentino R, Liu G, Pariser AR, et al. Cross-sector sponsorship of research in eosinophilic esophagitis: a collaborative model for rational drug development in rare diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:613–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative social research. 2000;1(2) Art 20; http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0002204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson P, Willke R, Burke L. A concept taxonomy and an instrument hierarchy: tools for establishing and evaluating the conceptual framework of a patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument as applied to product labeling claims. Value Health. 2009;12:1158–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH, et al. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA Perspective. Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S125–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bottomley A, Jones D, Claassens L. Patient-reported outcomes: assessment and current perspectives of the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration and the reflection paper of the European Medicines Agency. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLeod LD, Coon CD, Martin SA, et al. Interpreting patient-reported outcome results: US FDA guidance and emerging methods. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:163–169. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ Accessed May 4th 2011.

- 26.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic esophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–495. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norquist JM, Girman C, Fehnel S, et al. Choice of recall period for patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures: criteria for consideration. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1013–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straumann A, Bussmann C, Zuber M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:598–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pentiuk S, Putnam PE, Collins M, et al. Dissociation between symptoms and histologic severity in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:152–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817f0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation, in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.