Abstract

Scarring and tissue fibrosis represent a significant source of morbidity in the United States. Despite considerable research focused on elucidating the mechanisms underlying cutaneous scar formation, effective clinical therapies are still in the early stages of development. A thorough understanding of the various signaling pathways involved is essential to formulate strategies to combat fibrosis and scarring. While initial efforts focused primarily on the biochemical mechanisms involved in scar formation, more recent research has revealed a central role for mechanical forces in modulating these pathways. Mechanotransduction, which refers to the mechanisms by which mechanical forces are converted to biochemical stimuli, has been closely linked to inflammation and fibrosis and is believed to play a critical role in scarring. This review provides an overview of our current understanding of the mechanisms underlying scar formation, with an emphasis on the relationship between mechanotransduction pathways and their therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Mechanotransduction, Mechanical signaling, Fibrosis, Scarring

1. Introduction

The biological mechanisms underlying tissue repair after injury are among the most complex processes occurring in multicellular organisms. In mammals, the typical response to injury is fibrotic scar formation, which provides early restoration of tissue integrity rather than functional regeneration (Gurtner et al., 2008). Scar development serves as a rapid ‘patch’ response, providing a survival advantage as an evolutionarily conserved repair mechanism (Ting et al., 2005, Gurtner et al., 2008). Although fibrosis in the setting of cutaneous injury is highly visible, there are a variety of organ systems that demonstrate pathologic fibrotic response to injury, including lung tissue in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (King et al., 2011) and the cardiovascular system following ischemic insult (Chen and Frangogiannis, 2013). Fibroproliferative disease represents a major health burden globally and is directly or indirectly responsible for almost 50% of deaths in the developed world (Wynn, 2007).

The impact of mechanical forces on tissue fibrosis has been observed as early as the 19th century (Langer, 1861), but only recently have we begun to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms. Acute wound healing typically occurs through a complex cascade of carefully orchestrated biochemical and cellular events in overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and ultimately remodeling with scar formation (Folkman and Greenspan, 1975; Curtis and Seehar, 1978; Singer and Clark, 1999). Today we know that all phases of wound healing are influenced by mechanical forces (Agha et al., 2011) and there is increasing evidence that mechanical influences regulate post-injury inflammation and fibrosis across multiple organ systems (Pelosi and Rocco, 2008; Drakos et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2011, 2012). Although there has been recent progress in the understanding of mechanotransduction (the conversion of mechanical forces to biochemical signals) in fibrosis (Wang et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2012), the field of wound mechanobiology is still in its infancy (Carver and Goldsmith, 2013; Rustad et al., 2013). The utilization of biomechanical models to understand how mechanotransduction of microenvironmental cues influences the behavior of cells and tissues will help to identify novel therapeutic targets for mechanomodulatory approaches, as well as guide tissue engineering strategies. Innovative therapies based on these advances will potentially transform fibrotic healing into tissue regeneration.

2. Experimental models of tissue fibrosis

While early investigations of physical effects on cells and tissues relied on relatively simple and imprecise systems, in recent years the field of mechanobiology has advanced rapidly. The development of new in vitro and in vivo models to more precisely isolate and analyze the effects of mechanical forces has led to substantial progress in our understanding of their influence on biological processes (Carver and Goldsmith, 2013).

2.1. Mechanotransduction model systems in vitro

in vitro systems for the investigation of the biological effects of mechanical forces have evolved tremendously in the past five decades; from early hanging-drop culture methods of connective tissue cells (Bassett and Herrmann, 1961) to sophisticated systems capable of applying dynamic multiaxial strain to cells grown on deformable substrata (Wong et al., 2011). Fibroblasts, the key effector cells in fibrotic tissue deposition, have been the focus of numerous studies that have demonstrated the adoption of a fibroproliferative phenotype in response to mechanical stimulation. Fibroblast characteristics influenced by mechanical strain include matrix and inflammatory gene and protein expression, proliferation, motility and fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation (Lambert et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2005; Eckes et al., 2006; Chiquet et al., 2007; Kadi et al., 2008; Mammoto et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2012).

Similar changes to proliferative and migratory capacity have been observed in cytomechanical testing of keratinocytes (Yamazaki et al., 1996; Yano et al., 2004; Reno et al., 2009) with a recapitulation of the transcriptional and protein level changes in lung (Heise et al., 2011) and heart tissue (Yamazaki et al., 1996). These data collectively suggest a strong mechanobiological influence on wound healing and fibrosis throughout the body.

Recognizing that many cell types are mechanoresponsive with potential importance in pathologic processes, in vitro models to study the response to mechanical stimuli have been further refined. Standard 2-dimensional culture models, where stress is applied to a cell monolayer, have progressed to 3-dimensional systems that more closely resemble the in vivo environment (Derderian et al., 2005). A successful model that provides a more natural setting is the fibroblast-populated collagen lattice (FPCL), which was first proposed as a skin substitute for burn patients (Bell et al., 1979, 1981). Although it never achieved clinical popularity as a skin equivalent, this model was well received for the in vitro study of wound contraction and cell-matrix interactions (Dallon and Ehrlich, 2008; Grinnell and Petroll, 2010). Specifically, FPLCs allow integrin-mediated interactions of fibroblasts with normal extracellular matrix (ECM) substrate to be evaluated and take into account 3-dimensional paracrine biochemical crosstalk (Wong et al., 2012). Taking the in vitro assessment of mechanical cues one step further, novel systems designed to study the combined effects of stretch, substrate stiffness and the dynamic alteration of scaffold rigidity on resident cells have also been reported (Throm Quinlan et al., 2011; Guvendiren and Burdick, 2012).

Given the complexity of these cell-matrix interactions, even more intricate models have been developed that investigate the forces between living cells on a molecular level. Molecular tension sensors based on Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) technology (Forster, 1948) have been used to directly visualize mechanical cell interactions with single-molecule sensitivity (Na and Wang, 2008). These sensors can be applied to measure the distribution of forces generated by individual cell adhesion molecules and can detect physical interactions between cells and their substrates on a subcellular level (Wang and Wang, 2009). Furthermore, nanotechnology approaches, such as atomic force microscopy, magnetic force microscopy, and magnetic twisting cytometry, permit evaluation and manipulation of physical stimuli on a molecular level and have facilitated a more complete understanding of mechanobiological relationships (Lele et al., 2007; Sen and Kumar, 2010).

2.2. Mechanotransduction model systems in vivo

Although in vitro model systems have enabled significant progress in our understanding of mechanotransduction, in vivo, cells exist within a dynamic environment wherein spatiotemporal changes are brought about during development or disease (Mammoto and Ingber, 2010; Pathak and Kumar, 2012). To overcome the limitations of in vitro systems, several in vivo models have been developed to study the effects of mechanical forces on cell behavior.

Small animal models have been utilized to study the effects of physical modulation on unwounded skin, demonstrating that mechanical stress can have positive effects on epidermal regeneration via enhanced proliferation, angiogenesis and stem cell recruitment (Chin et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013). A positive impact of mechanical force has also been observed in wound healing and granulation tissue formation and is potentially the basis of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), a significant development in wound healing (Lancerotto et al., 2012).

While mechanical force has certain beneficial effects under specific circumstances, it is also a major factor in fibroproliferative processes, leading to tissue fibrosis and scarring. Our group has developed a mouse model of hypertrophic scarring using external application of mechanical stress on healing incisions (Aarabi. et al., 2007). Herein mechanical stress causes an infiltration of inflammatory cells and decreased apoptosis of local cells involved in the healing response, resulting in proliferative scarring (Aarabi et al., 2007). In further studies based on this model we were able to identify mechanically regulated genes (Wong et al., 2011) and demonstrate that mechanical force regulates fibrosis in part via an inflammatory Focal adhesion kinase - Extracellular signal-regulated kinase - Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (FAK-ERK-MCP-1) pathway (Wong et al., 2012). Specifically, our findings suggested that mechanical forces promote a pro-fibrotic environment via fibroblast secretion of inflammatory mediators and recruitment of inflammatory cells.

Interestingly, the impact of FAK signaling on fibrosis formation has also been demonstrated in lung tissue using a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model in mice (Lagares et al., 2012; Kinoshita et al., 2013). Bleomycin, originally developed as an anticancer agent, causes an inflammatory response resembling acute lung injury (ALI) and ultimately leads to the development of fibrosis, which can be markedly decreased by FAK inhibition (Moeller et al., 2008; Mouratis and Aidinis, 2011; Lagares et al., 2012).

Mechanotransduction pathways are also important in the myocardium, as pathological hypertrophy can result from the abnormal cardiac workloads associated with systemic hypertension, aortic stenosis, myocardial infarction or congenital defects of sarcomeric proteins (Jaalouk and Lammerding, 2009). Specifically, the response to continuous mechanical overload is a maladaptive remodeling of myocytes and the ECM, as well as increased interstitial fibrosis (Barry et al., 2008). In order to investigate the processes underlying these changes, multiple in vivo models of cardiac pressure overload have been developed, with the murine model of transverse aortic constriction (TAC) being the most widely used (Patten and Hall-Porter, 2009). First described by Rockman et al., it involves tying a 7-0 suture ligature around the aortic arch in mice and quantifying the pressure gradient across the stricture (Rockman et al., 1991). This and other animal models of cardiac fibrosis suggest that pathological hypertrophy can be prevented, or even reversed, by the modulation of signaling pathways known to be involved in mechanotransduction (Heineke and Molkentin, 2006).

While these small animal models have played a key role in our emerging understanding of biomechanical influences in vivo, models of higher fidelity are needed to accurately assess human wound repair physiology (Wong et al., 2011). Porcine skin anatomy is very similar to humans and therefore pig models have been developed to study human cutaneous mechanobiology. Applying these new large animal models, our laboratory has demonstrated that scar formation in the red Duroc pig occurs similarly to humans and that the degree of post-injury fibrosis directly correlated with the amount of tension imparted on the wound during healing. Importantly, we developed a topical device capable of off-loading these wounds and significantly blocking the fibrotic response (Gurtner et al., 2011).

Pigs have also recently been used to study the mechanical dynamics and sequalae of heart failure using a model of left ventricular pressure overload induced by progressive ascending aortic cuff inflation (Yarbrough et al., 2012). Similarly, large animal model systems such as porcine, canine and primate models play an important role in research on the mechanistics of fibrotic lung disease, with these models being used to generate a more physiologic pulmonary fibrotic response following application of asbestos, silica, bleomycin or radiation (Moore et al., 2013).

The observations made in small and large animal studies jointly speak to a significant involvement of mechanical cues in the development of scar tissue and fibrosis. These findings provide the basis for a deeper understanding of the pathology underlying fibroproliferative disease and advancements in its therapy.

3. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction

Through the process of mechanotransduction, cells are able to convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical or transcriptional changes (Alenghat and Ingber, 2002). This signal transduction involves proteins and molecules of the ECM, the cytoplasmic membrane, the cytoskeleton and the nuclear membrane, eventually affecting the nuclear chromatin at a genetic and epigenetic level (Wang et al., 2009). A system characterizing and linking all the different levels of mechanotransduction and their influence on genetic cell programs, known as tensional integrity or “tensegrity”, has been proposed by Ingber (Ingber, 1998). Originally described as an architectural concept (Fuller, 1961), this principle was adapted and developed by Ingber et al. to explain how cellular structure is affected by mechanical force. In spite of these attempts to comprehensively define the role of mechanical influences in molecular biology, a complete understanding of the complex mechanotransduction pathways in living organs remains elusive. Translating these findings into clinical therapies is a principal goal for researchers and clinicians. Moreover, despite the likely shared mechanisms responsible for mechanotransduction across cell and tissue types, our discussion of these pathways will focus on fibroblasts, in which these processes are best understood.

3.1. Extracellular Mechanisms

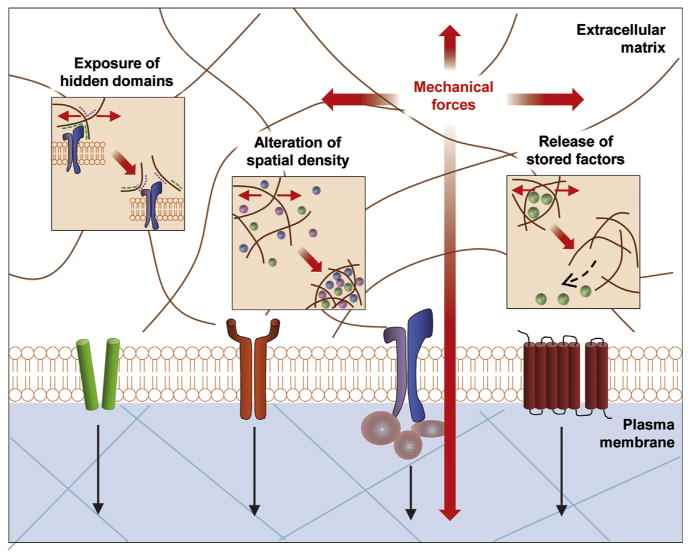

The ECM is a three dimensional network consisting of more than 300 different proteins and polysaccharides (Cromar et al., 2012). It accounts for more than 20% of human bodyweight and is the main source of structural support in multicellular organisms (Noguera et al., 2012). Much more than just an inert material passively providing support, the ECM is a dynamic and living component possessing multiple functions (Fig. 1), including playing a pivotal role in cell adhesion, migration, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis and mechanotransduction (Huxley-Jones et al., 2009; Oschman, 2009). Reciprocal communication of mechanical cues between the ECM and cells can even directly influence gene expression, as structural proteins have been described that link the ECM with nuclear chromatin, (Gieni and Hendzel, 2008), providing at least one mechanism of how physical cues from the ECM are able to alter cell functionality and phenotype (Discher et al., 2005).

Fig. 1.

Extracellular Mechanotransduction. The ECM is a dynamic structure possessing multiple functions and is directly regulated by mechanical force. Mechanical forces can expose hidden domains and alter spatial density of growth factors within the ECM, thereby influencing cell behavior. Finally, cytokines such as TGF-β can bind to ECM domains and be released based on mechanical cues (Wong et al., 2011). Reprint with permission.

Further supporting the dynamic influence of the ECM on cell behavior, tissue stiffness and rigidity have been connected with tumor growth and malignancy (Huang and Ingber, 2005). In fact alterations to the ECM can have a pro-oncogenic effect (Ingber, 2008), while correction of ECM structure can effectively reverse malignant behavior (Kenny and Bissell 2003). Not surprisingly, it is thought that micro-environmental cues can similarly influence scarring and fibrosis (Solon et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013), wherein scar progression resulting from a positive feedback loop involving the accumulation of ECM ultimately leads to increased matrix stiffness. This process in turn stimulates fibroblast proliferation and collagen production via mechanoresponsive cell surface receptors (Hadjipanayi et al., 2009; Hinz, 2009).

Besides direct regulation of cell behavior via ECM-cell membrane/cytoskeletal interactions, mechanical forces can also influence biological systems indirectly via conformational changes in the ECM. In particular, changes in ECM morphology can expose hidden domains and binding sites that have regulatory functions (Baneyx et al., 2002), while the spatio-temporal displacement of soluble and matrix bound effector molecules and growth factors, such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), by the ECM can lead to alterations of biological function (Hynes, 2009). Specifically, the TGF-ß superfamily has been reported to have a significant influence on fibrosis and inflammation (Hubmacher and Apte, 2013), with a deeper understanding of its mechanisms gained through the study of inherited connective tissue disorders with underlying TGF-β dysregulation (Doyle et al., 2012; Ogawa and Hsu, 2013). Utilizing this investigational approach, TGF-β was found to be tethered to the ECM via latent TGF-β-binding proteins (LTBPs), which are in turn anchored to fibrillin microfibrils and can be released and activated by integrin-mediated physical forces (Wipff and Hinz, 2008; Buscemi et al., 2011; Todorovic and Rifkin, 2012).

Given the multitude of ways that the ECM and its mechanics influence cell functionality and behavior, it becomes clear that this crosstalk holds a pivotal role in both health and disease. The integration of current knowledge with novel insights into how cell-matrix interactions govern cell and tissue fate will provide further insight into the development of therapies for fibroproli-ferative diseases.

3.2. Intracellular mechanisms

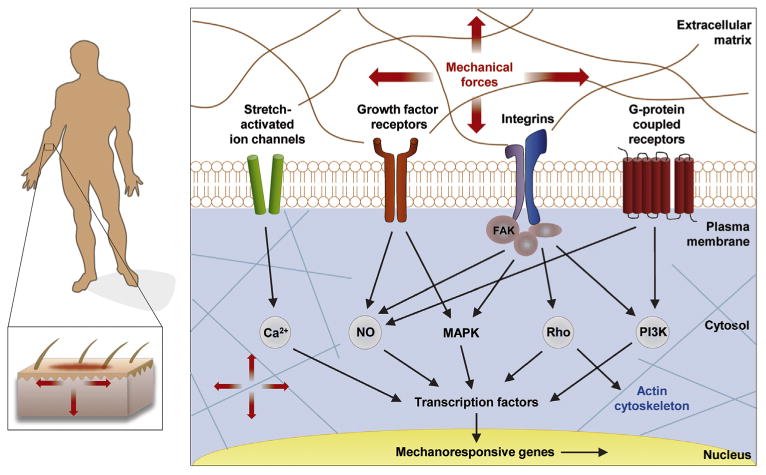

Recent efforts have led to an increased understanding of the key molecular links governing the intracellular signal transduction of physical signals from the ECM. While multiple interrelated signaling pathways have been shown to participate in the complex mechanism of intracellular mechanotransduction, some of the most important mediators responsible for transducing signals from the biomechanical environment include integrin-matrix interactions, growth factor receptors (e.g., for TGF-β), G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), mechanoresponsive ion channels (e.g., Ca2+), and cytoskeletal strain responses (Jaalouk and Lammerding, 2009; Wong et al., 2012) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Intracellular Mechanotransduction. The most important mediators of transduction signals from the biomechanical environment include integrin-matrix interactions, growth factor receptors (e.g., for TGF-β), G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), mechanoresponsive ion channels (e.g., Ca2+), and cytoskeletal strain responses. Once transmitted over the cell membrane, mechanical force activates multiple interrelated signaling pathways including calcium-dependent targets, nitric oxide signaling, mitogen-associated protein kinases (MAPKs), RhoGTPases, and phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) (Wong et al., 2011). Reprint with permission.

The most widely studied structures that transmit signals from the ECM are integrins. Integrins comprise a large family of heterodimeric transmembrane receptor proteins consisting of an a and β subunit. They possess a cytoplasmic domain, which is in contact with the actin cytoskeleton, and an extracellular domain able to bind to the molecules of the ECM (Schwarz and Gardel, 2012). Integrins are fundamentally involved in both “outside-in” transmission of environmental mechanical cues to the cell, and "inside-out" communication of cell traction forces (Schwarz and Gardel 2012). This bidirectional signaling process is modulated by various intracellular binding proteins, which associate with integrins to form large macromolecular structures, termed focal adhesions (Zaidel-Bar et al., 2007; Wehrle-Haller, 2012). The recruitment of these associating proteins, namely focal adhesion kinase (FAK), paxillin, talin and vinculin among others, and the subsequent maturation of focal adhesions themselves into advanced mechanoresponsive organelles is greatly augmented both by forces applied externally and internal traction forces (Chen et al., 2013; Dumbauld et al., 2013).

In addition to physical transmission from the ECM to the cytoskeleton and vice versa, all forces going through the focal adhesion complexes also lead to conformational changes in the complex macro-structure, which ultimately activates the non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase FAK via autophosphorylation. Moreover, while integrins have no intrinsic enzymatic activity, they can trigger downstream signaling pathways via FAK, demonstrating their ability to influence both mechanical and chemical cell signaling (Rustad et al., 2013).

Highlighting the key role that FAK plays in the mechanical stimulation of fibrosis, our laboratory recently demonstrated a mechanically activated pathway linking fibroblast FAK signaling with cutaneous scar formation (Wong et al., 2012). In this work, microarray analyses were first used to construct transcriptome networks of mechanically regulated genes, including FAK, with subsequent genetic and pharmacological FAK inhibition establishing a clear link between kinase activation and fibroproliferative injury caused by mechanical force. Interestingly, this work also identified extracellular-related kinase (Erk, part of the family of mitogen activated kinases [MAPKs]) as a critical mediator in the FAK related response to wound tension that leads to overproduction of collagen and the pro-fibrotic chemokine monocyte che-moattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) (Wong et al., 2012). Several studies have also suggested a role for other MAPKs including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 isoforms in the tension induced fibrotic response (Hofmann et al., 2004; Kook et al., 2011), though their specific contributions remain to be clarified.

Integrins, and therefore focal adhesions, can also have a direct influence on the activation and release of TGF-β from its reservoir in the extracellular latent complex (Margadant and Sonnenberg 2010; Buscemi et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011). This cytokine has been strongly linked to numerous fibrotic diseases, and acts mainly via the transforming growth factor-β receptor 2 and its downstream effector proteins Smad 2 and 3 to induce several pro-fibrotic mechanisms, including collagen production and fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. (Leask and Abraham, 2004; LeBleu et al., 2013)

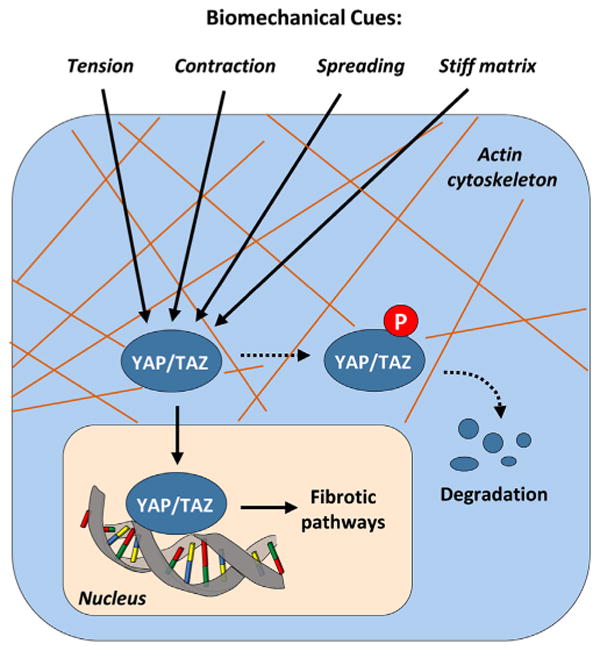

Another major target of focal adhesion components and FAK signaling is the Rho family of GTPases. RhoGTPases, in particular, have been shown to influence cell tension, motility, adherence and cytoskeletal dynamics, as well as stimulate myofibroblast differentiation (Chiquet et al., 2007; Haudek et al., 2009), indicating their likely broad mechanosensing function. There is also growing evidence of a connection between RhoGTPases and two downstream effectors of the mammalian Hippo pathway, a highly conserved signaling pathway involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, stem cell function and malignant transformation (Fig. 3) (Zhao et al., 2011; Tremblay and Camargo, 2012). In fact, the mechanosensitive proteins YAP (Yes-associated protein) and TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif, also known as WWTR1) have emerged as major regulators of organ development and regeneration (Dupont et al., 2011; Halder et al., 2012; Hiemer and Várelas, 2013), and have been shown to be essential for dermal wound healing (Lee et al., 2013). Among their transcriptional targets are connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and TGF-β (Varelas et al., 2010; Dupont et al., 2011), with both growth factors playing important roles in the development of fibrosis, as well as transglutaminase-2, a molecule involved in ECM deposition, turnover and crosslinking (Raghunathan et al., 2013). The Hippo pathway has also been linked to components of the Wnt-β-Catenin pathway (Heallen et al., 2011), which itself has been shown to be mechanoresponsive and play a critical role in myofibroblast differentiation and wound fibrosis (Cheon et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2011; Samuel et al., 2011).

Fig. 3.

The Hippo Pathway in Mechanotransduction. The highly conserved mammalian Hippo pathway, with its two main downstream effectors YAP and TAZ, represents an important connection between biomechanical cues, the cytoskeleton and cell behavior. Among its transcriptional targets are connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and TGF-β, both of which playing important roles in the development of fibrosis, as well as transglutaminase-2, a molecule involved in ECM deposition, turnover and crosslinking. This makes YAP and TAZ potentially attractive therapeutic targets.

Interestingly, this research on the influences of the downstream effectors YAP and TAZ has taken place without full characterization of the upstream signals of the Hippo pathway. Nonetheless, Yu et al. recently revealed that GPCRs, in particular G12/13 and Gs coupled receptors, act upstream of the transcriptional coactivators YAP/TAZ to either activate or inhibit the Hippo pathway (Yu et al., 2012). Interestingly, GPCRs also act as general cell surface mechanoreceptors and have been linked to many of the same intracellular pathways activated by focal adhesion complexes (Jaalouk and Lammerding, 2009; Wong et al., 2012). While, more investigation is needed to fully elucidate the role of the Hippo pathway in mechanotransduction and fibrosis, its profibrotic gene targets and substantial interactions with several key pathways related to scar development make YAP and TAZ potentially attractive therapeutic targets.

Another intracellular mechanism of mechanotransduction involves stretch activated, calcium-dependant ion channels (Goto et al., 2010). These mechanoresponsive calcium channels are key factors in the regulation of cytoskeletal function. Furthermore the influx of Ca2+ in response to mechanical strain can influence MAPKs, participate intimately in the GPCR system, and is thought to promote profibrotic gene expression (Huang et al., 2012).

In addition to the transduction of forces from the outside, a cell can also produce and sense mechanical cues from within. Cell traction forces (CTFs) are generated by the cells own cytoskeleton and applied to the surrounding ECM or neighboring cells (Discher et al., 2005; Lemmon et al., 2009). This physical communication has implications for development, disease, and regeneration, including the alteration of gene expression in stem cell differentiation. (Buxboim et al., 2010).

In reviewing this body of work, the complexity of the mechanisms by which cells "feel" and interact with their environment becomes readily apparent. Nonetheless, in order to most effectively address the specific deficiencies underlying fibroproliferative diseases, future efforts are needed to gain a more complete understanding of the relative role of the different mechanisms involved in physiological and pathological mechanotransduction.

4. Mechanotransduction in tissue engineering

Complex tissue and organ engineering holds promise for a variety of clinical implications, including the replacement of tissues/organs affected by fibrotic disease. Interestingly, mechan-otransduction has been recognized as a key factor in the engineering of various tissues and organs, such as bone (Mullender et al., 2004), heart (Parker and Ingber, 2007), muscle (Agrawal and Ray 2001), ligaments (Vunjak-Novakovic et al., 2004), cartilage (Freed et al., 1997) and bladder (Korossis et al., 2006). For example, matrix production by tissue-engineered bone is enhanced when the growing tissue is subjected to mechanical forces in bioreactor culture (Morris et al., 2010), and similar findings support the benefit of complex multi-dimensional strain on the engineering of ligaments (Altman et al., 2002). Looking to physiologic developmental processes for engineering insight, the spatial and temporal maturation of critical organs, such as the heart, are also strongly connected to mechanical cues (Ott et al., 2008). This suggests that a recapitulation of these forces will be required in tissue engineering approaches to construct bioartificial replacement organs using progenitor cells, a concept that is reinforced by the demonstrated sensitivity of stem cell differentiation to mechanical cues (Subramony et al., 2013). The design of novel biomaterials that mimic the complex hierarchical mechano-structure of native tissues is therefore critical to the field of regenerative medicine (Shi et al., 2010).

5. Possibilities for therapeutic intervention

In parallel to tissue engineering approaches, direct interventions on pathologic fibrotic processes are being explored. Tissue fibrosis generally results from aberrant signaling in response to injury, which leads to disruption of homeostasis between collagen production and collagen degradation. Therapies seeking to alleviate fibrosis must therefore restore collagen homeostasis by modulating either its production or degradation.

5.2. Pharmacological approaches

Pharmacological approaches for the treatment of fibrosis typically involve the use of targeted molecular therapies designed to up- or down-regulate pathways involved in collagen homeostasis. Typically, these therapies are designed to decrease collagen synthesis (Yamaguchi et al., 2012; Beyer et al., 2013; Diao et al., 2013; Tomcik et al., 2013).

TGF-β has been identified as a critical mediator of collagen synthesis, and therefore fibrosis, which makes it a promising target for anti-fibrotic therapy. TGF-βl and 2 have pro-fibrotic effects, whereas TGF-β3 has anti-fibrotic effects (Murata et al., 1997). The major therapeutic strategies involving the TGF-β pathway thus include using neutralizing antibodies to TGF-βl and 2, or increasing TGF-β3. Neutralizing antibodies bind directly to the ligand and prevent receptor activation, and TGF-β1 and 2 specific antibodies have been successfully used to reduce fibrosis in a number of organs in animal models (Shah et al., 1992, 1994; McCormick et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2003). Unfortunately, the preclinical success of TGF-β antibodies has not translated into clinical efficacy. The first clinical trial assessing an anti-TGF-β antibody (metelimumab) was used for patients with systemic sclerosis and demonstrated no significant improvement in their skin condition (Denton et al., 2007). A similar lack of benefit was seen in a Phase II clinical trial using imatinib mesylate, an inhibitor of TGF-β and platelet-derived growth factor signaling, for the treatment of scleroderma (Prey et al., 2012).

The use of TGF-β3 has also been effectively tested in animal models, where it was found to reduce fibrosis and scarring by decreasing TGF-β1/2 levels (Shah et al., 1995; O'Kane and Ferguson 1997; Ohno et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013). However, similar to the clinical challenges observed with TGF-β1 and 2 specific antibodies, no significant mitigation of scar development could be observed with TGF-β3 in an international Phase III clinical trial (Renovo, 2011).

A number of other therapeutic targets have shown promise for the mitigation of mechanically induced fibrosis in preclinical models, including the hedgehog pathway (Horn et al., 2012), extracellular cross-linking enzymes (transglutaminases, lysyl oxidases, and prolyl hydroxylases) (Barry-Hamilton et al., 2010; Kolb and Gauldie, 2011; Olsen et al., 2011), early growth response gene-1 (Yamaguchi et al., 2012), canonical Wnt (Beyer et al., 2013), heat shock protein 90 (Tomcik et al., 2013), histone deacetylase (Diao et al., 2013) and IL-10, which modulates fibrosis by intercepting specific but varied intracellular signaling pathways (Reitamo et al., 1994; Yamamoto et al., 2001; Yuan and Varga, 2001; Nakagome et al., 2006, Occleston et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2013). Although remarkable progress has been made in targeting pro-fibrotic pathways experimentally, clinical translation of these therapies remains an ongoing challenge.

5.2. Mechanomodulatory approaches

An alternative approach to limiting fibrosis in the setting of cutaneous injury is modulating environmental cues by mechanical off-loading. As outlined above, mechanical tension plays a significant role in the development of fibrosis (Wong et al., 2012; Rustad et al., 2013), and compression dressings (Ward 1991; Akaishi et al., 2010; Engrav et al., 2010; Li-Tsang et al., 2010; Steinstraesser et al., 2011) and even paper tape (Atkinson et al., 2005) have demonstrated some efficacy in scar reduction.

Taking this concept one step further, active mechanical offloading (as opposed to passive tissue approximation) has also demonstrated efficacy in both animal and clinical trials, potentially reducing fibrosis by influencing multiple signaling pathways with mechano-receptive elements (Gurtner et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2013). Moreover, a phase I clinical trial (Gurtner et al., 2011) has demonstrated that stress-shielding of half of an abdominoplasty incision leads to significant improvements in scar appearance compared to the contralateral side where the incision was allowed to heal in the presence of significant mechanical tension. These findings suggest that a mechanomodulatory approach might be a promising way to address the multiple pathways involved in the fibrotic response, at least in the cutaneous setting. Looking ahead, this approach should be refined for individual patients and wound sites, as region-specific differences in skin tension (Wong et al., 2012) may require a customization of mechanomodulatory environments in order to most efficiently reduce scarring and optimize healing across wound settings.

6. Conclusion and future perspectives

Scarring and fibrosis represent a significant healthcare burden, with elucidation of the underlying mechanotransductive signaling pathways playing a crucial role in understanding scar formation and developing targeted therapeutics to interrupt these processes. The emergence of highly translational mechanotransduction modeling systems has enabled researchers to precisely measure and manipulate the mechanical cell environment. Accordingly, investigations into the effect of mechanical force on hypertrophic scarring have already led to significant advancements in medical device development for the treatment of wounds (Gurtner et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2013), with some of these products already entering the clinical setting. Nonetheless, a more complete understanding of the mechanisms of scar formation should lead to increasingly sophisticated therapeutic concepts that may ultimately reduce, prevent and perhaps even reverse fibrosis across all organ systems.

Acknowledgments

Funding for mechanobiology research conducted in our laboratory has been provided by the Hagey Family Endowed Fund in Stem Cell Research and Regenerative Medicine (DOD #W81XWA0-08-2-0032), the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine (DOD #W81XWA0-08-2-0032) (U.S. Department of Defense), and the Oak Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: GCG is listed on the following patent assigned to Stanford University: inhibition of focal adhesion kinase for control of scar tissue formation (No: 2013/0165,463). GCG and MTL have equity positions in Neodyne Biosciences, Inc., a startup company developing a device to shield wounds from tension to minimize postoperative scarring.

Conflict of interest statement: DD, ZNM, VWW, RCR, MR, MJ, MH and AW have no potential conflicts of interest, affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed herein.

References

- Aarabi S, Bhatt KA, Shi Y, Paterno J, Chang EI, Loh SA, Holmes JW, Longaker MT, Yee H, Gurtner GC. Mechanical load initiates hypertrophic scar formation through decreased cellular apoptosis. FASEB J. 2007;21(12):3250–3261. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8218com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agha R, Ogawa R, Pietramaggiori G, Orgill DP. A review of the role of mechanical forces in cutaneous wound healing. J Surg Res. 2011;171(2):700–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal C, Ray RB. Biodegradable polymeric scaffolds for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55(2):141–150. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200105)55:2<141::aid-jbm1000>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaishi S, Akimoto M, Hyakusoku H, Ogawa R. The tensile reduction effects of silicone gel sheeting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):109e–111e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181df7073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alenghat FJ, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction: all signals point to cytoskeleton, matrix, and integrins. Sci STKE. 2002;2002(119):pe6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.119.pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman GH, Lu HH, Horan RL, Calabro T, Ryder D, Kaplan DL, Stark P, Martin I, Richmond JC, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Advanced bioreactor with controlled application of multi-dimensional strain for tissue engineering. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124(6):742–749. doi: 10.1115/1.1519280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JA, McKenna KT, Barnett AG, McGrath DJ, Rudd M. A randomized, controlled trial to determine the efficacy of paper tape in preventing hypertrophic scar formation in surgical incisions that traverse Langer's skin tension lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(6):1648–1656. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000187147.73963.a5. discussion 1657-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BB, Lawson WE, Oury TD, Sisson TH, Raghavendran K, Hogaboam CM. Animal models of fibrotic lung disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49(2):167–179. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0094TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baneyx G, Baugh L, Vogel V. Fibronectin extension and unfolding within cell matrix fibrils controlled by cytoskeletal tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(8):5139–5143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072650799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry SP, Davidson SM, Townsend PA. Molecular regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(10):2023–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry-Hamilton V, Spangler R, Marshall D, McCauley S, Rodriguez HM, Oyasu M, Mikels A, Vaysberg M, Ghermazien H, Wai C, Garcia CA, Velayo AC, Jorgensen B, Biermann D, Tsai D, Green J, Zaffryar-Eilot S, Holzer A, Ogg S, Thai D, Neufeld G, Van Vlasselaer P, Smith V. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenviron-ment Nat. Med. 2010;16(9):1009–1017. doi: 10.1038/nm.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett CA, Herrmann I. Influence of oxygen concentration and mechanical factors on differentiation of connective tissues in vitro. Nature. 1961;190:460–461. doi: 10.1038/190460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Ehrlich HP, Buttle DJ, Nakatsuji T. Living tissue formed in vitro and accepted as skin-equivalent tissue of full thickness. Science. 1981;211(4486):1052–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.7008197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Ivarsson B, Merrill C. Production of a tissue-like structure by contraction of collagen lattices by human fibroblasts of different proliferative potential in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76(3):1274–1278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Reichert H, Akan H, Mallano T, Schramm A, Dees C, Palumbo-Zerr K, Lin NY, Distler A, Gelse K, Varga J, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. Blockade of canonical Wnt signalling ameliorates experimental dermal fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1255–1258. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AC, Fiore VF, Sulchek TA, Barker TH. Physical and chemical microenvironmental cues orthogonally control the degree and duration of fibrosis-associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. J Pathol. 2013;229(1):25–35. doi: 10.1002/path.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscemi L, Ramonet D, Klingberg F, Formey A, Smith-Clerc J, Meister JJ, Hinz B. The single-molecule mechanics of the latent TGF-beta1 complex. Curr Biol. 2011;21(24):2046–2054. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxboim A, Ivanovska IL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity, cytoskeletal forces and physics of the nucleus: how deeply do cells ‘feel’ outside and in? J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 3):297–308. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver W, Goldsmith EC. Regulation of tissue fibrosis by the biomechanical environment. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:101979. doi: 10.1155/2013/101979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Kishimoto Y, Hasan A, Welham NV. TGF-beta3 modulates the inflammatory environment and reduces scar formation following vocal fold mucosal injury. Dis Models Mech. 2013 doi: 10.1242/dmm.013326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH, Chen WL, Sider KL, Yip CY, Simmons CA. beta-catenin mediates mechanically regulated, transforming growth factor-beta1-induced myofibroblast differentiation of aortic valve interstitial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(3):590–597. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.220061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Fibroblasts in post-infarction inflammation and cardiac repair. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(4):945–953. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Pasapera AM, Koretsky AP, Waterman CM. Orientation-specific responses to sustained uniaxial stretching in focal adhesion growth and turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(26):E2352–E2361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221637110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon SS, Cheah AY, Turley S, Nadesan P, Poon R, Clevers H, Alman BA. beta-Catenin stabilization dysregulates mesenchymal cell proliferation, motility, and invasiveness and causes aggressive fibromatosis and hyperplastic cutaneous wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(10):6973–6978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102657399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MS, Lancerotto L, Helm DL, Dastouri P, Prsa MJ, Ottensmeyer M, Akaishi S, Orgill DP, Ogawa R. Analysis of neuropeptides in stretched skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):102–113. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a81542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiquet M, Tunc-Civelek V, Sarasa-Renedo A. Gene regulation by mechanotransduction in fibroblasts. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32(5):967–973. doi: 10.1139/H07-053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromar GL, Xiong X, Chautard E, Ricard-Blum S, Parkinson J. Toward a systems level view of the ECM and related proteins: a framework for the systematic definition and analysis of biological systems. Proteins. 2012;80(6):1522–1544. doi: 10.1002/prot.24036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AS, Seehar GM. The control of cell division by tension or diffusion. Nature. 1978;274(5666):52–53. doi: 10.1038/274052a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallon JC, Ehrlich HP. A review of fibroblast-populated collagen lattices. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(4):472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton CR, Merkel PA, Furst DE, Khanna D, Emery P, Hsu VM, Silliman N, Streisand J, Powell J, Akesson A, Coppock J, Hoogen F, Herrick A, Mayes MD, Veale D, Haas J, Ledbetter S, Korn JH, Black CM, Seibold JR. Recombinant human anti-transforming growth factor beta1 antibody therapy in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase I/II trial of CAT-192. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):323–333. doi: 10.1002/art.22289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derderian CA, Bastidas N, Lerman OZ, Bhatt KA, Lin SE, Voss J, Holmes JW, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Mechanical strain alters gene expression in an in vitro model of hypertrophic scarring. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(1):69–75. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000168160.86221.e9. discussion 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao JS, Xia WS, Yi CG, Yang Y, Zhang X, Xia W, Shu MG, Wang YM, Gui L, Guo SZ. Histone deacetylase inhibitor reduces hypertrophic scarring in a rabbit ear model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):61e–69e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318290f698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310(5751):1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Gerber EE, Dietz HC. Matrix-dependent perturbation of TGFbeta signaling and disease. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(14):2003–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakos SG, Kfoury AG, Selzman CH, Verma DR, Nanas JN, Li DY, Stehlik J. Left ventricular assist device unloading effects on myocardial structure and function: current status of the field and call for action. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26(3):245–255. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328345af13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbauld DW, Lee TT, Singh A, Scrimgeour J, Gersbach CA, Zamir EA, Fu J, Chen CS, Curtis JE, Craig SW, Garcia AJ. How vinculin regulates force transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(24):9788–9793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216209110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, Elvassore N, Piccolo S. Role of YAP / TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474(7350):179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckes B, Zweers MC, Zhang ZG, Hallinger R, Mauch C, Aumailley M, Krieg T. Mechanical tension and integrin alpha 2 beta 1 regulate fibroblast functions. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2006;11(1):66–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engrav LH, Heimbach DM, Rivara FP, Moore ML, Wang J, Carrougher GJ, Costa B, Numhom S, Calderon J, Gibran NS. 12-Year within-wound study of the effectiveness of custom pressure garment therapy. Burns. 2010;36(7):975–983. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J, Greenspan HP. Influence of geometry on control of cell growth. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;417(3-4):211–236. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(75)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster T. Zwischenmolekulare energiewanderung und fluoreszenz. Ann Phys. 1948;2(1-2):55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Freed LE, Langer R, Martin I, Pellis NR, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tissue engineering of cartilage in space. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94(25):13885–13890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B. Tensegrity. Portfolio and Art News Annual. 1961;(4):112–127. 144, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Gieni RS, Hendzel MJ. Mechanotransduction from the ECM to the genome: are the pieces now in place? J Cell Biochem. 2008;104(6):1964–1987. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M, Ikeyama K, Tsutsumi M, Denda S, Denda M. Calcium ion propagation in cultured keratinocytes and other cells in skin in response to hydraulic pressure stimulation. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224(1):229–233. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F, Petroll WM. Cell motility and mechanics in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:335–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, Dauskardt RH, Wong VW, Bhatt KA, Wu K, Vial IN, Padois K, Korman JM, Longaker MT. Improving cutaneous scar formation by controlling the mechanical environment: large animal and phase I studies. Ann Surg. 2011;254(2):217–225. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318220b159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453(7193):314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guvendiren M, Burdick JA. Stiffening hydrogels to probe short- and long-term cellular responses to dynamic mechanics. Nat Commun. 2012;3:792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjipanayi E, Mudera V, Brown RA. Close dependence of fibroblast proliferation on collagen scaffold matrix stiffness. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3(2):77–84. doi: 10.1002/term.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Dupont S, Piccolo S. Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(9):591–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haudek SB, Gupta D, Dewald O, Schwartz RJ, Wei L, Trial J, Entman ML. Rho kinase-1 mediates cardiac fibrosis by regulating fibroblast precursor cell differentiation. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83(3):511–518. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL, Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332(6028):458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1199010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(8):589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise RL, Stober V, Cheluvaraju C, Hollingsworth JW, Garantziotis S. Mechanical stretch induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelia via hyaluronan activation of innate immunity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(20):17435–17444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiemer SE, Varelas X. Stem cell regulation by the Hippo pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(2):2323–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B. Tissue stiffness, latent TGF-betal activation, and mechanical signal transduction: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11(2):120–126. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann M, Zaper J, Bernd A, Bereiter-Hahn J, Kaufmann R, Kippenberger S. Mechanical pressure-induced phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in epithelial cells via Src and protein kinase C. Biochem. Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316(3):673–679. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn A, Kireva T, Palumbo-Zerr K, Dees C, Tomcik M, Cordazzo C, Zerr P, Akhmetshina A, Ruat M, Distler O, Beyer C, Schett G, Distler JH. Inhibition of hedgehog signalling prevents experimental fibrosis and induces regression of established fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(5):785–789. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Akaishi S, Ogawa R. Mechanosignaling pathways in cutaneous scarring. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304(8):589–597. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Ingber DE. Cell tension, matrix mechanics, and cancer development. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(3):175–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yang N, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Sun Y, Morris SW, Ding Q, Thannickal VJ, Zhou Y. Matrix stiffness-induced myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by intrinsic mechanotransduction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(3):340–348. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0050OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubmacher D, Apte SS. The biology of the extracellular matrix: novel insights. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25(1):65–70. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835b137b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley-Jones J, Pinney JW, Archer J, Robertson DL, Boot-Handford RP. Back to basics—how the evolution of the extracellular matrix underpinned vertebrate evolution. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90(2):95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2008.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 2009;326(5957):1216–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.1176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. The architecture of life. Sci Am. 1998;278(1):48–57. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0198-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Tensegrity-based mechanosensing from macro to micro. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;97(2-3):163–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaalouk DE, Lammerding J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):63–73. doi: 10.1038/nrm2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadi A, Fawzi-Grancher S, Lakisic G, Stoltz JF, Muller S. Effect of cyclic stretching and TGF-beta on the SMAD pathway in fibroblasts. Biomed Mater Eng. 2008;18(Suppl 1):S77–S86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PA, Bissell MJ. Tumor reversion: correction of malignant behavior by microenvironmental cues. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(5):688–695. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King TE, Jr, Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, Aono, Azuma, Kishi, Takezaki, Kishi, Makino, Okazaki, Uehara, Izumi, Sone, Nishioka Antifibrotic effects of focal adhesion kinase inhibitor in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49(4):536–543. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0277OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook SH, Jang YS, Lee JC. Involvement of JNK-AP-1 and ERK-NF-kappaB signaling in tension-stimulated expression of type I collagen and MMP-1 in human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111(6):1575–1583. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00348.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korossis S, Bolland F, Ingham E, Fisher J, Kearney J, Southgate J. Review: tissue engineering of the urinary bladder: considering structure-function relationships and the role of mechanotransduction. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(4):635–644. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagares D, Busnadiego O, Garcia-Fernandez RA, Kapoor M, Liu S, Carter DE, Abraham D, Shi-Wen X, Carreira P, Fontaine BA, Shea BS, Tager AM, Leask A, Lamas S, Rodriguez-Pascual F. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase prevents experimental lung fibrosis and myofibroblast formation. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(5):1653–1664. doi: 10.1002/art.33482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert CA, Soudant EP, Nusgens BV, Lapiere CM. Pretranslational regulation of extracellular matrix macromolecules and collagenase expression in fibroblasts by mechanical forces. Lab Invest. 1992;66(4):444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancerotto L, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Mechanisms of action of microdeformational wound therapy. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(9):987–992. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer K. Zur Anatomie und Physiologie der Haut. Über die Spaltbarkeit der Cutis. Sitzungsbericht der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Wiener Kaiserlichen Academie der Wissenschaften. 1861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004;18(7):816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBleu VS, Taduri G, O'Connell J, Teng Y, Cooke VG, Woda C, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/nm.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ran Byun, Furutani-Seiki, Hong, Jung YAP and TAZ regulate skin wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;134:518–525. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lele TR, Sero JE, Matthews BD, Kumar S, Xia S, Montoya-Zavala M, Polte T, Overby D, Wang N, Ingber DE. Tools to study cell mechanics and mechanotransduction. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;83:443–472. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon CA, Chen CS, Romer LH. Cell traction forces direct fibronectin matrix assembly. Biophys J. 2009;96(2):729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Tsang CW, Zheng YP, Lau JC. A randomized clinical trial to study the effect of silicone gel dressing and pressure therapy on posttraumatic hypertrophic scars. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(3):448–457. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181db52a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Weintraub, Kaplan, Januszyk, Cowley, McLaughlin, Beasley, Gurtner, Longaker The embrace device significantly decreases scarring following scar revision surgery in a randomized control trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;133(2):398–405. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000436526.64046.d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chua CH, Wu XL, Wang DR, Yin DM, Cui L, Cao YL, Longaker MT. Inhibiting scar formation in rat cutaneous wounds by blocking TGF-beta signaling. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;83(1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammoto A, Mammoto T, Ingber DE. Mechanosensitive mechanisms in transcriptional regulation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 13):3061–3073. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammoto T, Ingber DE. Mechanical control of tissue and organ development. Development. 2010;137(9):1407–1420. doi: 10.1242/dev.024166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margadant C, Sonnenberg A. Integrin-TGF-beta crosstalk in fibrosis, cancer and wound healing. EMBO Rep. 2010;11(2):97–105. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick LL, Zhang Y, Tootell E, Gilliam AC. Anti-TGF-beta treatment prevents skin and lung fibrosis in murine sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease: a model for human scleroderma. J Immunol. 1999;163(10):5693–5699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(3):362–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris HL, Reed CI, Haycock JW, Reilly GC. Mechanisms of fluid-flow-induced matrix production in bone tissue engineering. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2010;224(12):1509–1521. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouratis MA, Aidinis V. Modeling pulmonary fibrosis with bleomycin. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(5):355–361. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328349ac2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb MR, Gauldie J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the matrix is the message. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):627–629. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1282ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullender M, El Haj A, Yang Y, Van Duin M, Burger E, Klein-Nulend J. Mechanotransduction of bone cellsin vitro: mechanobiology of bone tissue. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2004;42(1):14–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02351006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata H, Zhou L, Ochoa S, Hasan A, Badiavas E, Falanga V. TGF-beta3 stimulates and regulates collagen synthesis through TGF-betal-dependent and independent mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108(3):258–262. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12286451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na S, Wang N. Application of fluorescence resonance energy transfer and magnetic twisting cytometry to quantitate mechano-chemical signaling activities in a living cell. Sci Signal. 2008;1(34) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.134pl1. nihpa69932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagome K, Dohi M, Okunishi K, Tanaka R, Miyazaki J, Yamamoto K. in vivo IL-10 gene delivery attenuates bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the production and activation of TGF-beta in the lung. Thorax. 2006;61(10):886–894. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguera R, Nieto OA, Tadeo I, Farinas F, Alvaro T. Extracellular matrix, biotensegrity and tumor microenvironment. An update and overview Histol Histopathol. 2012;27(6):693–705. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane S, Ferguson MW. Transforming growth factor beta s and wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29(1):63–78. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occleston NL, O'Kane S, Goldspink N, Ferguson MW. New therapeutics for the prevention and reduction of scarring. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13(21-22):973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa R, Hsu CK. Mechanobiological dysregulation of the epidermis and dermis in skin disorders and in degeneration. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17(7):817–822. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Hirano S, Kanemaru S, Kitani Y, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Mizuta M, Tateya I, Nakamura T, Ito J. Transforming growth factor beta3 for the prevention of vocal fold scarring. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(3):583–589. doi: 10.1002/lary.22389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen KC, Sapinoro RE, Kottmann RM, Kulkarni AA, Iismaa SE, Johnson GV, Thatcher TH, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Transglutaminase 2 and its role in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):699–707. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0013OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oschman JL. Charge transfer in the living matrix. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2009;13(3):215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14(2):213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KK, Ingber DE. Extracellular matrix, mechanotransduction and structural hierarchies in heart tissue engineering. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2007;362(1484):1267–1279. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak A, Kumar S. Independent regulation of tumor cell migration by matrix stiffness and confinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(26):10334–10339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118073109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten RD, Hall-Porter MR. Small animal models of heart failure: development of novel therapies, past and present. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(2):138–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.839761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P, Rocco PR. Effects of mechanical ventilation on the extracellular matrix. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(4):631–639. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prey S, Ezzedine K, Doussau A, Grandoulier AS, Barcat D, Chatelus E, Diot E, Durant C, Hachulla E, de Korwin-Krokowski JD, Kostrzewa E, Quemeneur T, Paul C, Schaeverbeke T, Seneschal J, Solanilla A, Sparsa A, Bouchet S, Lepreux S, Mahon FX, Chene G, Taieb A. Imatinib mesylate in scleroderma-associated diffuse skin fibrosis: a phase II multicentre randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(5):1138–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan VK, Morgan JT, Dreier B, Reilly CM, Thomasy SM, Wood JA, Ly I, Tuyen BC, Hughbanks M, Murphy CJ, Russell P. Role of substratum stiffness in modulating genes associated with extracellular matrix and mechanotransducers YAP and TAZ. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(1):378–386. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitamo S, Remitz A, Tamai K, Uitto J. Interleukin-10 modulates type 1 collagen and matrix metalloprotease gene expression in cultured human skin fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(6):2489–2492. doi: 10.1172/JCI117618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reno F, Traina V, Cannas M. Mechanical stretching modulates growth direction and MMP-9 release in human keratinocyte monolayer. Cell Adhes Migr. 2009;3(3):239–242. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.3.8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renovo Juvista EU Phase 3 Trial Results 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Ross RS, Harris AN, Knowlton KU, Steinhelper ME, Field LJ, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR. Segregation of atrial-specific and inducible expression of an atrial natriuretic factor transgene in an in vivo murine model of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(18):8277–8281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad KC, Wong VW, Gurtner GC. The role of focal adhesion complexes in fibroblast mechanotransduction during scar formation. Differentiation. 2013;86(3):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel MS, Lopez JI, McGhee EJ, Croft DR, Strachan D, Timpson P, Munro J, Schroder E, Zhou J, Brunton VG, Barker N, Clevers H, Sansom OJ, Anderson KI, Weaver VM, Olson MF. Actomyosin-mediated cellular tension drives increased tissue stiffness and beta-catenin activation to induce epidermal hyperplasia and tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(6):776–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz US, Gardel ML. United we stand: integrating the actin cytoskeleton and cell-matrix adhesions in cellular mechanotransduction. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 13):3051–3060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Kumar S. Combining mechanical and optical approaches to dissect cellular mechanobiology. J Biomech. 2010;43(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Control of scarring in adult wounds by neutralising antibody to transforming growth factor beta. Lancet. 1992;339(8787):213–214. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90009-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Neutralising antibody to TGF-beta 1,2 reduces cutaneous scarring in adult rodents. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 5):1137–1157. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.5.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Neutralisation of TGF-beta 1 and TGF-beta 2 or exogenous addition of TGF-beta 3 to cutaneous rat wounds reduces scarring. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 3):985–1002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Votruba AR, Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Nanotechnology in drug delivery and tissue engineering: from discovery to applications. Nano Lett. 2010;10(9):3223–3230. doi: 10.1021/nl102184c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi JH, Guan H, Shi S, Cai WX, Bai XZ, Hu XL, Fang XB, Liu JQ, Tao K, Zhu XX, Tang CW, Hu DH. Protection against TGF-betal-induced fibrosis effects of IL-10 on dermal fibroblasts and its potential therapeutics for the reduction of skin scarring. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305(4):341–352. doi: 10.1007/s00403-013-1314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, Chen X, Mi L, Walz T, Springer TA. Latent TGF-beta structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474(7351):343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(10):738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solon J, Levental I, Sengupta K, Georges PC, Janmey PA. Fibroblast adaptation and stiffness matching to soft elastic substrates. Biophys J. 2007;93(12):4453–4461. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinstraesser L, Flak E, Witte B, Ring A, Tilkorn D, Hauser J, Langer S, Steinau HU, Al-Benna S. Pressure garment therapy alone and in combination with silicone for the prevention of hypertrophic scarring: randomized controlled trial with intraindividual comparison. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(4):306e–313e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182268c69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramony SD, Dargis BR, Castillo M, Azeloglu EU, Tracey MS, Su A, Lu HH. The guidance of stem cell differentiation by substrate alignment and mechanical stimulation. Biomaterials. 2013;34(8):1942–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throm Quinlan AM, Sierad LN, Capulli AK, Firstenberg LE, Billiar KL. Combining dynamic stretch and tunable stiffness to probe cell mechanobiology in vitro. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting SB, Caddy J, Hislop N, Wilanowski T, Auden A, Zhao LL, Ellis S, Kaur P, Uchida Y, Holleran WM, Elias PM, Cunningham JM, Jane SM. A homolog of Drosophila grainy head is essential for epidermal integrity in mice. Science. 2005;308(5720):411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1107511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V, Rifkin DB. LTBPs, more than just an escort service. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(2):410–418. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomcik M, Zerr P, Pitkowski J, Palumbo-Zerr K, Avouac J, Distler O, Becvar R, Senolt L, Schett G, Distler JH. Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibition targets canonical TGF-beta signalling to prevent fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay AM, Camargo FD. Hippo signaling in mammalian stem cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(7):818–826. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varelas X, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Narimatsu M, Weiss A, Cockburn K, Larsen BG, Rossant J, Wrana JL. The Crumbs complex couples cell density sensing to Hippo-dependent control of the TGF-beta-SMAD pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;19(6):831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vunjak-Novakovic G, Altman G, Horan R, Kaplan DL. Tissue engineering of ligaments. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:131–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JG, Miyazu M, Xiang P, Li SN, Sokabe M, Naruse K. Stretch-induced cell proliferation is mediated by FAK-MAPK pathway. Life Sci. 2005;76(24):2817–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang N. FRET and mechanobiology. Integr Biol (Camb) 2009;1(10):565–573. doi: 10.1039/b913093b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RS. Pressure therapy for the control of hypertrophic scar formation after burn injury. A history and review J Burn Care Rehabil. 1991;12(3):257–262. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrle-Haller B. Structure and function of focal adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24(1):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipff PJ, Hinz B. Integrins and the activation of latent transforming growth factor betal-an intimate relationship. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87(8-9):601–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Akaishi S, Longaker MT, Gurtner GC. Pushing back: wound mechanotransduction in repair and regeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(11):2186–2196. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Levi K, Akaishi S, Schultz G, Dauskardt RH. Scar zones: region-specific differences in skin tension may determine incisional scar formation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(6):1272–1276. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824eca79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Longaker MT, Gurtner GC. Soft tissue mechanotransduction in wound healing and fibrosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(9):981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Paterno J, Sorkin M, Glotzbach JP, Levi K, Januszyk M, Rustad KC, Longaker MT, Gurtner GC. Mechanical force prolongs acute inflammation via T-cell-dependent pathways during scar formation. FASEB J. 2011;25(12):4498–4510. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-178087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Rustad KC, Akaishi S, Sorkin M, Glotzbach JP, Januszyk M, Nelson ER, Levi K, Paterno J, Vial IN, Kuang AA, Longaker MT, Gurtner GC. Focal adhesion kinase links mechanical force to skin fibrosis via inflammatory signaling. Nat Med. 2012;18(1):148–152. doi: 10.1038/nm.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Sorkin M, Glotzbach JP, Longaker MT, Gurtner GC. Surgical approaches to create murine models of human wound healing. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:969618. doi: 10.1155/2011/969618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(3):524–529. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Takihara T, Chambers RA, Veraldi KL, Larregina AT, Feghali-Bostwick CA. A peptide derived from endostatin ameliorates organ fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(136):136ra71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Eckes B, Krieg T. Effect of interleukin-10 on the gene expression of type I collagen, fibronectin, and decorin in human skin fibroblasts: differential regulation by transforming growth factor-beta and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281(1):200–205. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T, Komuro I, Yazaki Y. Molecular aspects of mechanical stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996:163–164. 197–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00408658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano S, Komine M, Fujimoto M, Okochi H, Tamaki K. Mechanical stretching in vitro regulates signal transduction pathways and cellular proliferation in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(3):783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough WM, Mukherjee R, Stroud RE, Rivers WT, Oelsen JM, Dixon JA, Eckhouse SR, Ikonomidis JS, Zile MR, Spinale FG. Progressive induction of left ventricular pressure overload in a large animal model elicits myocardial remodeling and a unique matrix signature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(1):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, Zhao J, Yuan H, Tumaneng Kv, Li H, Fu XD, Mills GB, Guan KL. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150(4):780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Varga J. Transforming growth factor-beta repression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in dermal fibroblasts involves Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(42):38502–38510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R, Itzkovitz S, Ma'ayan A, Iyengar R, Geiger B. Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(8):858–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb0807-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(8):877–883. doi: 10.1038/ncb2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SB, Wang J, Chiang CA, Sheng LL, Li QF. Mechanical stretch upregulates Sdf-1alpha in skin tissue and induces migration of circulating bone marrow-derived stem cells into the expanded skin. Stem Cells. 2013;31(12):2703–2713. doi: 10.1002/stem.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]