This study compared health-related quality of life and psychological morbidity in a hospital-based sample of first-generation migrants and Australian-born Anglo cancer patients and explored the relative contribution of ethnicity versus migrant-related variables. In multiple linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, socioeconomic status, time since diagnosis, and type of cancer, migrants who develop cancer have worse psychological and health-related quality of life outcomes than Anglo-Australians.

Keywords: Health disparities, Health-related quality of life, Anxiety, Depression, Migrants, Cancer

Abstract

Background.

Multiethnic societies face challenges in delivering evidence-based culturally competent health care. This study compared health-related quality of life and psychological morbidity in a hospital-based sample of first-generation migrants and Australian-born Anglo cancer patients, controlling for potential confounders related to migrant status. Further, it explored the relative contribution of ethnicity versus migrant-related variables.

Methods.

Eligible participants, recruited via 16 oncology clinics in Australia, included those over the age of 18, diagnosed with cancer (any type or stage) within the previous 12 months and having commenced treatment at least 1 month previously.

Results.

In total, 571 migrant patients (comprising 145 Arabic, 248 Chinese, and 178 Greek) and a control group of 274 Anglo-Australian patients participated. In multiple linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, socioeconomic status, time since diagnosis, and type of cancer, migrants had clinically significantly worse health-related quality of life (HRQL; 3.6–7.3 points on FACT-G, p < .0001), higher depression and anxiety (both p < .0001), and higher incidence of clinical depression (p < .0001) and anxiety (p = .003) than Anglo-Australians. Understanding the health system (p < .0001 for each outcome) and difficulty communicating with the doctor (p = .04 to .0001) partially mediated the impact of migrancy. In migrant-only analyses, migrant-related variables (language difficulty and poor understanding of the health system), not ethnicity, predicted outcomes.

Conclusion.

Migrants who develop cancer have worse psychological and HRQL outcomes than Anglo-Australians. Potential targets for intervention include assistance in navigating the health system, translated information, and cultural competency training for health professionals.

Implications for Practice:

Multiethnic societies are facing the challenge of health disparity among immigrant and minority groups. International organizations have called for more research to increase understanding of this under-researched population and to identify the determinants of these disparities. This study contributes to closing the literature gap by documenting the extent of cancer disparities for psychological well-being and quality of life in the Australian immigrant population and delineating the relative contribution of ethnicity versus migrant-related variables in such disparities. The findings will provide an evidence base to guide cultural competence in cancer care, a need recognized internationally.

Introduction

Recently, many countries have experienced rapid growth of ethnically diverse and foreign-born populations, bringing cultural differences to medical encounters, which can complicate health care delivery. Health disparities between majority and minority populations have been widely reported. Several international organizations have issued position papers calling for more research on health disparities and identification of key service issues that would guide “culturally competent” health services, accessible to all patients, regardless of racial or ethnic background [1, 2].

Cancer, now the world’s biggest killer, has become a focus of disparity research given its chronicity and extensive impact. Disparities in cancer incidence and survival among migrants and minorities have been well documented. In the U.S., for example, minorities are expected to have approximately a twofold higher risk of developing cancer in the next 20 years compared with white Americans [3]. However, little is known about patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in this population.

In the limited studies identified in a recent systematic review on this topic [4], ethnic minority groups were consistently identified as more vulnerable in terms of psychological morbidity and quality of life, even after adjustment for socioeconomic status. However, most studies focused on the Hispanic minority group in the U.S., and results may not be generalizable to other countries, particularly those with different health systems and ethnic composition. Secondly, most studies examined ethnicity differences and overlooked migrant status. The World Health Organization has explicitly stated that “both being a migrant and belonging to an ethnic minority are frequently associated with impaired health and poorer access to health services” [5] and asserted that both migrant status and ethnicity should be considered in disparities research.

In a study evaluating the impact of both migrancy and ethnicity on PRO in Australian cancer survivors [6], we found inferior psychological and quality of life (QoL) outcomes in migrants but no differences between ethnic subgroups. This study identified two common predictors of PROs across the study’s cultural subgroups: language difficulty and problems understanding the health system.

The current study aimed to extend current knowledge to include migrant patients who were in the active treatment phase of the cancer trajectory, which represents the time of highest need for information, support, and practical assistance. To gain a better insight into migrant health issues, PROs were compared for foreign-born migrants versus Anglo-Australians, controlling for potential confounders related to migrant status. Furthermore, this study sought to explore the relative contribution of ethnicity versus migrant-related factors in explaining migrant outcomes. The results will inform development of evidence-based guidelines for migrant cancer care.

The hypotheses were:

Migrants with cancer will have worse PROs than Anglo-Australians in terms of psychological morbidity and QoL.

Difficulty communicating with health professionals and problems understanding the health system will mediate the effect of migrant status on PROs.

Within the migrant group only, English ability and knowledge of the health system will predict PROs, regardless of ethnicity.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study surveyed first-generation migrant cancer patients in Australia from Arabic-, Greek-, or Chinese-speaking backgrounds, who represent the most prevalent language groups [7]. A control group of Anglo-Australian-born patients was included. Eligibility criteria for the study included being over the age of 18, being diagnosed with cancer (any type or stage) within the previous 12 months, and having commenced treatment at least 1 month previously.

Procedure

A community advisory group for each language group, comprising consumers, health care professionals (nurses, general practioners, and oncologists), social workers, psychologists, community leaders, and religious leaders guided the cultural competence of the study. Recruitment was conducted at 16 oncology clinics across New South Wales, Victoria, and the Northern Territory in Australia. Ethical approvals were obtained from all relevant ethical review boards.

Potentially eligible participants were identified from clinic lists using surnames as an indicator of ethnicity and confirmed by oncologists. Immigrants’ surnames were entered into a surname database developed by our research group to identify people of probable or possible Arabic, Chinese, or Greek ancestry [6]. They were then approached in person at clinics by a bilingual research assistant, who confirmed patients’ birthplaces and self-identified ethnicities, obtained informed consent, and provided research materials in patients’ preferred languages. Participants completed a questionnaire booklet and mailed it back using a postage-paid envelope. Missing data were minimized by phoning respondents. Participants were informed that they could call a toll-free number to reach a bilingual researcher for help completing the questionnaire. Nonrespondents also received a reminder call to check whether they needed help completing the questionnaire. Clinical details were collected from participating hospitals. Aggregated, deidentified data were released by participating hospitals on nonparticipants.

Measures

Except for those measures already available and validated in the required languages (the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] [8, 9] and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General [FACT-G] [10]), translation of documents/measures proceeded according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer translation protocol [11]. Discrepancies after translation and back-translation were identified, discussed, and resolved, and the questionnaires were field-tested as recommended by Schuman [12] and subsequently revised.

Demographic details were obtained from patients including years lived in Australia, marital and employment status, religion, education level, difficulty communicating with doctors (not at all to very often), and understanding of the Australian health system (very well/well versus not so well/not well at all). Only migrants rated their confidence speaking and understanding English (very confident/confident versus not so confident/not confident at all).

Clinical details including cancer type and stage (early versus late) at the time of recruitment were recorded.

Psychological morbidity was assessed using the HADS [13], comprising seven items measuring anxiety and seven measuring depression. Each subscale has a score range of 0–21.This scale was established as the optimal measure of anxiety and depression for psycho-oncology studies in a recent review [14].

Quality of life was assessed using the FACT-G [15], a 27-item, widely used measure of QoL in cancer with high reliability (Chronbach’s α = 0.9) and validity. The FACT-G consists of four subscales assessing well-being in physical, emotional, social, and functional domains, with higher scores reflecting better QoL.

In this study, HADS and FACT-G had a high internal consistency with Chronbach’s α ≥ 0.9 for both migrants and Anglo-Australians.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding source had no role in any part of this study, except for financial support. The corresponding author had full access to all data and final responsibility for the decision to submit.

Statistical Analyses

Quality of life, anxiety, and depression were compared between migrants and Anglo-Australians in unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models. The adjusted models were prespecified and included socioeconomic and disease-related variables: language group, age, sex, education (low, medium, and high), socioeconomic status (SES; continuously, as the index of relative social advantage and disadvantage score) [16], marital or partnered status (yes or no); cancer type (breast, prostate, colorectal, lung, hepatobiliary, and other), cancer stage (early [primary] or late [metastatic]), and currently on chemotherapy/radiation treatment (yes or no). Migrant-related variables (difficulty communicating with the doctor, understanding of the health system, and language competency) were not included in these models because of their high correlation with migrant status and because we believed they were mediators.

Prevalence of clinical levels of anxiety and depression were computed using the HADS cutoff value of >10 [17]. Logistic regression was used to compute odds ratios to compare the three migrant groups with Anglo-Australians. The Sobel test [17] and Baron and Kenny’s methods [18] were used to examine whether difficulty understanding the health care system and difficulty communicating with the doctor mediated the effect of migrant status (as a binary variable) and each of the outcomes.

Multiple linear regression models were used in the migrant-only sample to assess the determinant roles of ethnicity versus migrant-specific factors: understanding of the health system and a fine-grained language variable measured only in migrants (i.e., confidence understanding English). Because difficulty communicating with the doctor and years in Australia were highly correlated with confidence understanding English, these factors were not included in this analysis. The model also included socioeconomic and disease-related variables mentioned previously in this section.

Results

Participants

Figure 1 shows the study flow. Over the 24-month study period, 1,449 of 1,603 potentially eligible patients were confirmed to be eligible and invited to participate in the study; 1,250 consented, and 903 returned the questionnaire (overall response rate of 62%). Fifty-eight patients in the Anglo-Australian control group who were born outside Australia (e.g., U.K., New Zealand) were excluded, yielding a final dataset of 845 subjects for statistical analyses. There were 571 migrants (comprising 145 Arabic, 248 Chinese, and 178 Greek) and a control group of 274 Anglo-Australians. Note that response rates for Anglo-Australians (73%), Arabic (49%), Chinese (68%), and Greek (53%) participants varied slightly, with fewer Arabic people responding than other groups.

Figure 1.

Study flow.

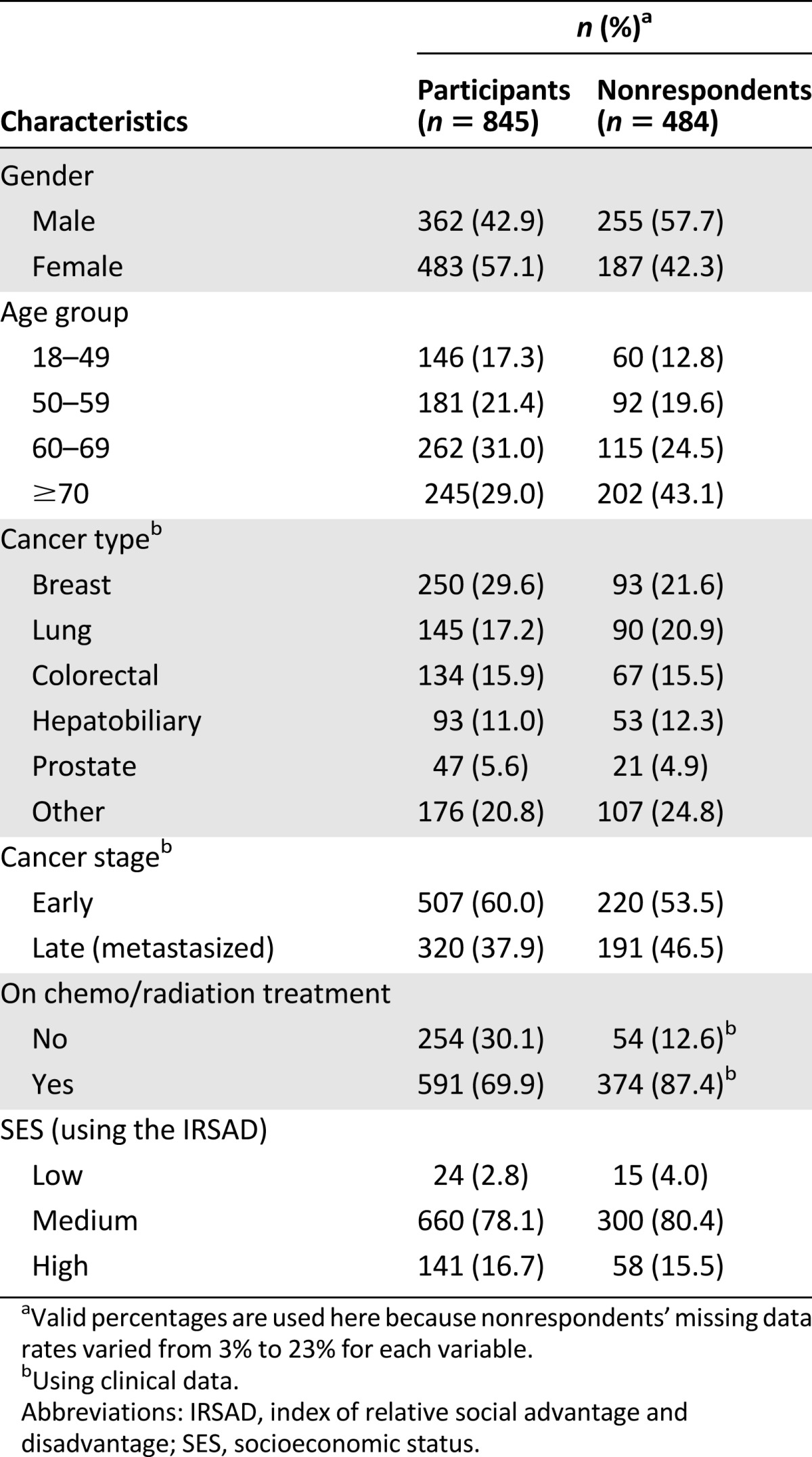

Deidentified data were obtained from participating hospitals on nonrespondents (Table 1). Compared with participants, more nonrespondents were male, were over 70 years old, had late-stage cancer, and were currently receiving chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics for participants vs. nonrespondents

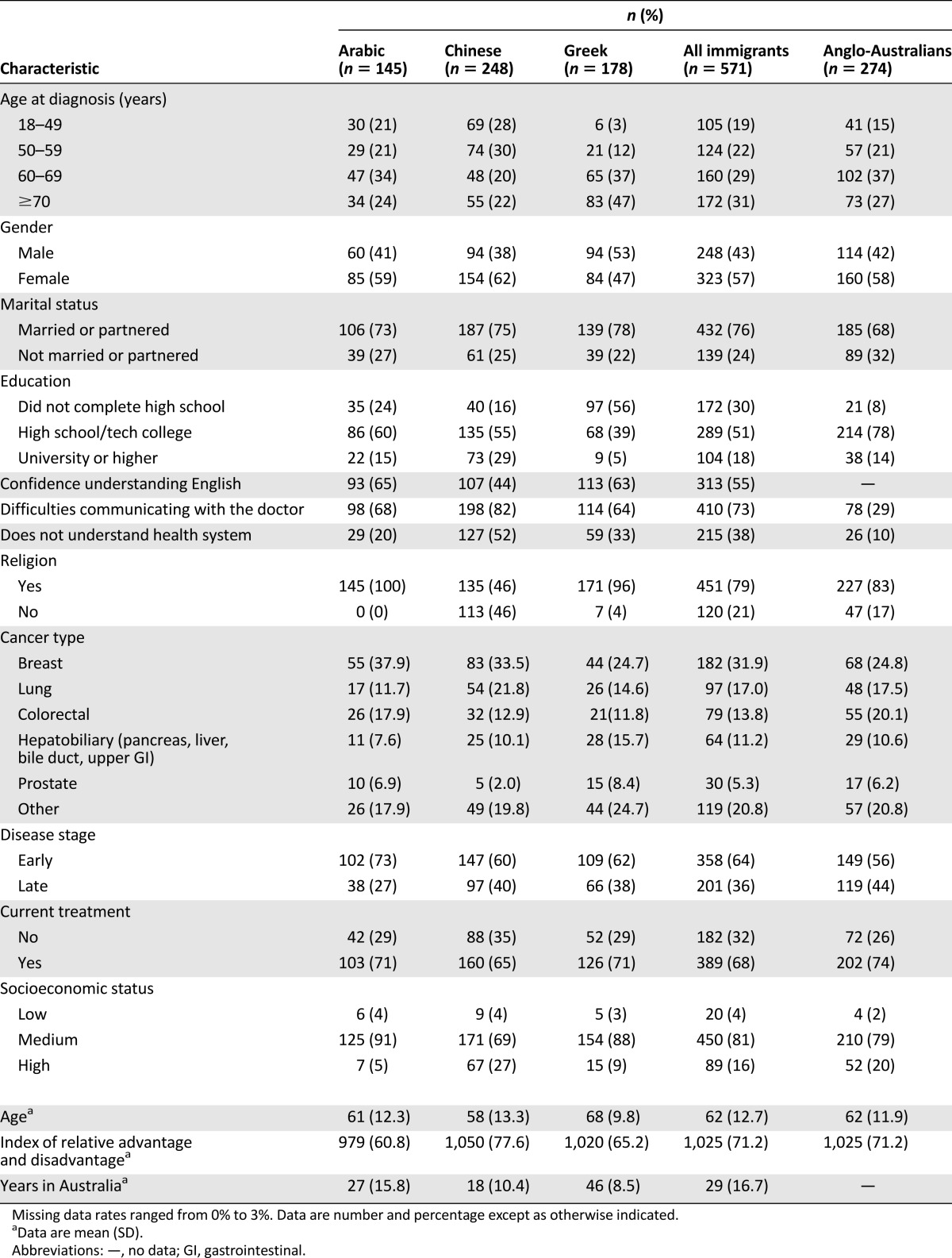

Table 2 shows demographic and disease characteristics of study participants. Except for gender and marital status, distributions of each categorical variable varied significantly (p < .05) among the four cultural groups. These variables were adjusted for in all statistical analyses.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by language group

Compared with Anglo-Australians, a significantly higher proportion of migrants reported problems understanding the health system (38% vs. 10%). Among the migrant groups, many reported lack of confidence understanding English (Arabic, 35%; Chinese, 56%; and Greek, 37%, respectively).

Differences Between Groups in Psychological Morbidity and QoL

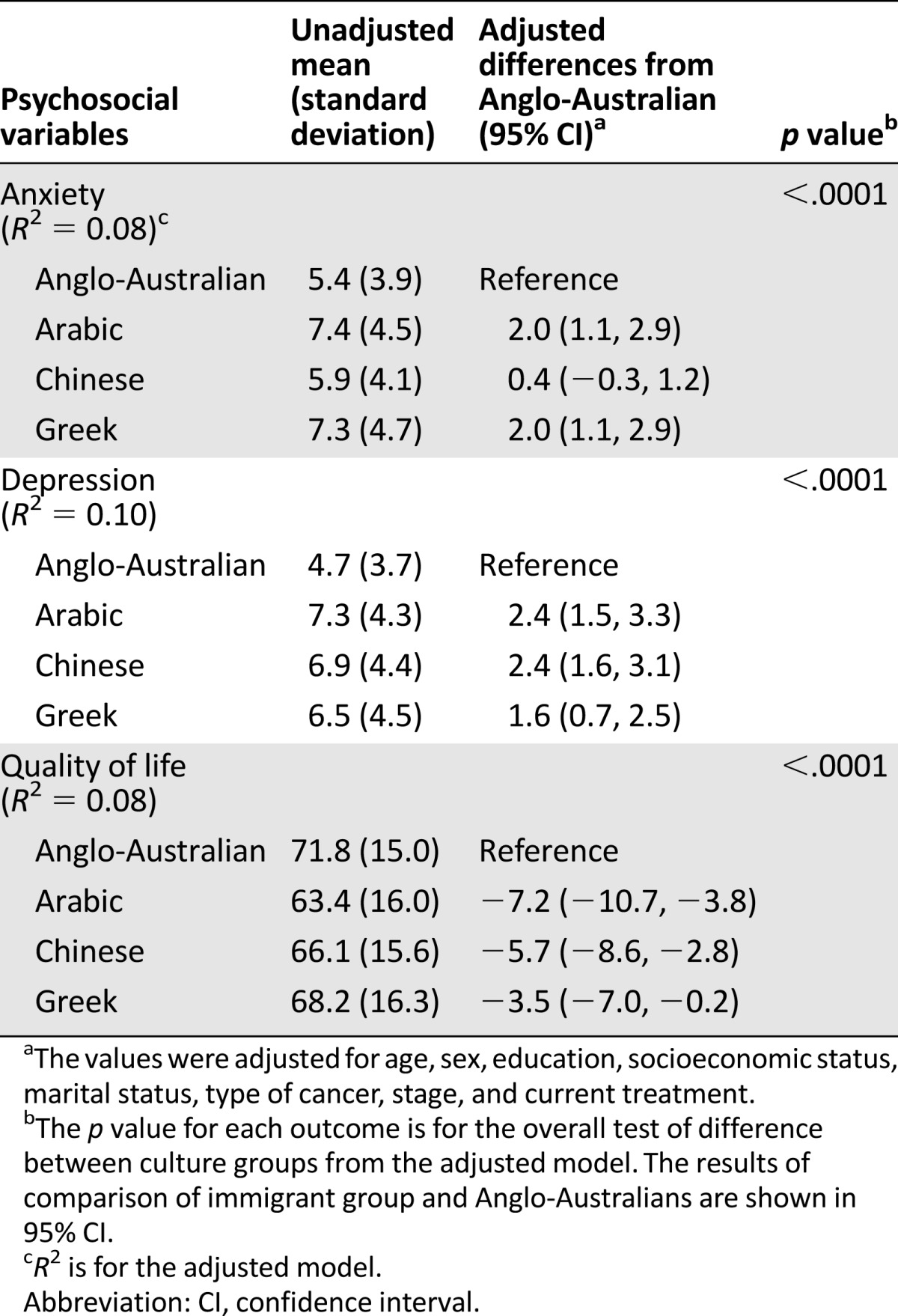

Hypothesis 1 was supported. In adjusted multivariate analyses, compared with Anglo-Australians, migrant participants had significantly higher levels of anxiety (R2 = 0.08, p < .0001), depression (R2 = 0.10, p < .0001), and lower levels of quality of life (R2 = 0.08, p < .0001), as shown in Table 3. Comparison of means between individual migrant groups with Anglo-Australians showed that all migrant groups were disadvantaged on all three outcomes, except for Chinese participants, whose anxiety levels were equivalent to those of Anglo-Australians. Arabic participants had the highest levels of anxiety and depression, as well as the lowest QoL.

Table 3.

Unadjusted means (standard deviations) of anxiety, depression, and quality of life and adjusted mean differences (95% confidence intervals) between immigrants and Anglo-Australians

Estimated differences in QoL scores compared with Anglo-Australians was 7.3 for Arabic migrants, 5.8 for Chinese migrants, and 3.6 for Greek migrants, meeting the threshold of minimal important difference of between 3 and 7 using the FACT-G (QoL) [19].

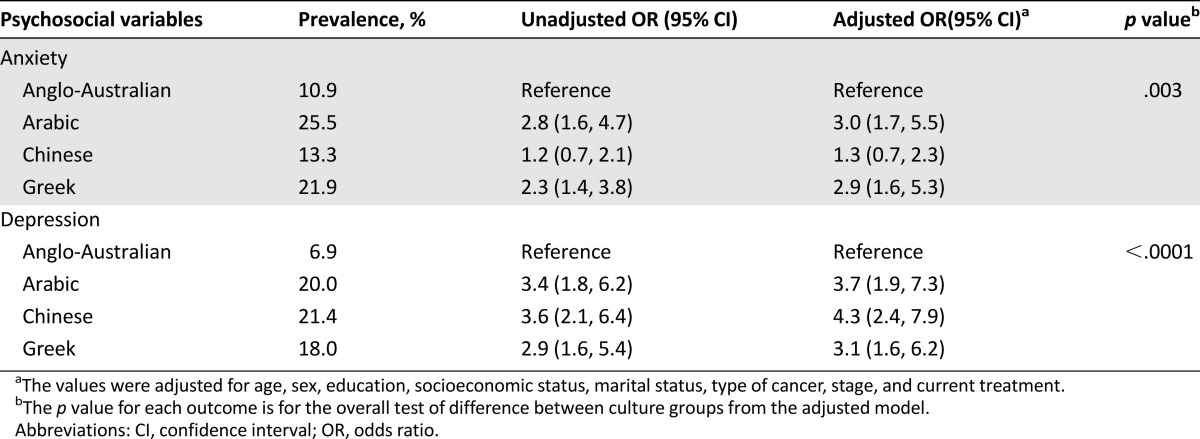

The estimated prevalence of clinical depression was 20% for Arabic participants, 21% for Chinese, 18% for Greek, and 7% for Anglo Australian (p < .0001). The estimated prevalence of clinical anxiety was 26% for Arabic participants, 13% for Chinese, 22% for Greek, and 11% for Anglo-Australian (p = .003). Compared with their Anglo-Australian counterparts, migrants had a three to four times higher risk of clinical depression and a one to three times higher risk of anxiety (Table 4), controlling for potential confounding socioeconomic and disease-related variables.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for clinical levels of depression and anxiety (95% confidence intervals) for immigrants compared with Anglo-Australians

Migrant Status Predicting PROs

In models that included all participants, migrant status was statistically significant for all three outcomes. Other predictors were age for anxiety; SES, treatment, and stage for depression; and age, SES, and treatment for QoL. There were no statistically significant interactions between migrant status and any of the candidate covariates. These are not substantially different from the estimates shown in Table 5 for migrants only.

Table 5.

Factors associated with anxiety, depression, and quality of life among immigrants

Mediating Factors

Hypothesis 2 was supported. Understanding the health system partially mediated the relationship between migrant status (migrant versus Anglo-Australian) and anxiety, depression, and QoL (p < .0001 for each). The indirect effect of understanding the health system accounted for 25% of the total effect for anxiety, 21% of the total effect of depression, and 30% for QoL.

Difficulties communicating with the doctor also significantly mediated anxiety (indirect effect = 21%, p = .04), depression (indirect effect = 26%, p = .0001), and QoL (indirect effect = 46%, p < .0001). This implies, as an example, that nearly half of the effect of migrant status on QoL is explained by whether the participant had difficulty communicating with the doctor.

Migrant-Specific Variables Predicting Migrants’ Cancer Adjustment

In regression analyses investigating which variables are associated with anxiety, depression, and QoL for migrants only, hypothesis 3 is generally supported. Ethnicity predicted only anxiety (p = .001), with the Chinese sample reporting lower anxiety. Conversely, understanding the health system was associated with lower values of anxiety (p = .008), lower depression (p = .03), and higher QoL (p = .003). Confidence understanding English was associated with lower values of anxiety (p = .003), lower depression (p = .01), and higher QoL (p = .02). These models explained 12.0%, 10.4%, and 13.3% of the variance (R2) for anxiety, depression, and QoL, respectively. The results are shown in Table 5.

Discussion

This study is the first to comprehensively assess the prevalence and predictors of psychological morbidity and QoL among migrants with cancer in Australia. In line with existing evidence [4], the results suggest that migrant cancer patients who come from Arabic-, Chinese-, and Greek-speaking backgrounds have higher levels of anxiety and depression, as well as inferior QoL, compared with their Australian-born Anglo counterparts. Migrants had a three to four times higher risk of clinical levels of depression and a one to three times higher risk of clinical levels of anxiety, controlling for potentially confounding demographic and disease variables.

Our results are generally consistent with data from other studies. For example, a British study reported a mean HADS score of 6.9 for anxiety (compared with 5.9–7.4 in our sample) and 7.4 for depression (compared with 6.5–7.3 in our sample) in Asian British patients [20], whereas two U.S. studies reported mean FACT-G scores of 56–60 for Latino Americans and 65 for Asian Americans [21, 22] (compared with 63–68 in our sample). In the current study, the estimated prevalence of clinical depression and clinical anxiety for Anglo-born-Australians was 7% and 11%, respectively, which are similar to results of other studies [23, 24], suggesting that the control group was also representative.

This study has pinpointed two variables that may place migrants at a disadvantage when they receive cancer care, namely their inadequate understanding of the health system and lack of English (and consequent difficulties communicating with the health care team). These factors predicted outcomes across the three migrant groups, indicating that these are challenges facing most newcomers in a host country and likely to be generic to most multiethnic Western countries. The lack of predictive ability of ethnicity in migrant outcomes further reinforces the need to learn more about the key determinants underlying health disparity instead of subscribing to overly prescriptive guidelines about specific ethnic groups.

Despite worse migrant outcomes in general, it is noteworthy that the Chinese group appeared more resilient to anxiety than the Arabic and Greek groups. A recent study with breast cancer patients in Singapore postulated that Asians were less prone to anxiety than Anglo-Australians. Although our results did not suggest Chinese participants had a lower prevalence of clinical anxiety than Anglo-Australians, this is certainly worth further exploration. Chinese cancer patients in Australia receive significant support from community-based cancer support organizations, who actively recruit through many of the hospitals participating in this study. Conversely, there are far fewer support groups available to Greek and Arabic patients. This may mean Chinese patients are better supported in gaining information and managing their anxiety. On the other hand, this finding may be due to cultural differences in illness perception and coping mechanisms.

Implications

Our results suggest that migrants require specific support to optimize their cancer care. Cancer requires a multidisciplinary care model to address the whole range of care and support needs (physical, emotional, informational, practical, and financial), increasing the challenge for patients in navigating the health system. Patient navigation programs have received increasing attention for their effectiveness in improving access to quality cancer care and system efficiency [25]. A recent study of the feasibility of a culturally targeted patient navigation program has shown that such a service is welcomed by potential consumers, who viewed it as a useful means to cater to their needs and preferences [26].

Interventions to overcome language barriers may include provision of interpreting services and greater access to translated information materials. Our recent study of interpreters has identified a potential expansion of their role as patient advocates [27], which may represent one pathway forward. A recent study comparing audiotaped content of medical consultations with migrants and those with Anglo-Australians found that oncologists spoke less to migrants and were more likely to delay responses to or ignore cues given by migrants [28], suggesting cross-cultural training of health professionals may be required.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

Despite inclusion of a range of demographic, clinical, and migrant variables, a considerable amount of the variance was not explained by the regression models. It is recognized that people respond to cancer in different ways depending on the culture-specific explanatory models and attitudes they hold about cancer [29]. It is possible that such cultural factors might explain more of the variance in outcomes. A recent qualitative study suggested that migrants reported a sense of cultural estrangement from culturally discordant health professionals even when they had no problem understanding English [30]. Future research on cultural factors would complement our findings in understanding of cancer disparity among migrant populations.

This study had a large sample that allowed subgroup analyses of outcomes for different ethnic groups. However, heterogeneity of the sample should not be ignored. This study classified migrant groups based on their language spoken and self-identified ethnicity. Within each language group were people from many different countries of origin (e.g., Arabic people born in Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan) where social and political structures differ significantly and also people with varied causes of migration, leading to variations in psychosocial needs. More migrant studies are needed to explore such potential differences.

Because of prospective recruitment, it was not possible to match Anglo-Australian and immigrant groups on disease and demographic variables. There were significant differences between the groups on a number of variables, which we controlled for in analyses. Nevertheless, some caution must be applied in interpreting the results because of intergroup differences.

In this study, two very widely used PRO measures in cancer research (i.e., the HADS and FACT-G) were selected to allow comparison with norms and other study samples. Although both of these scales have been translated using gold-standard approaches and have been cross-culturally validated in some cultures, not all language versions have been subjected to psychometric analysis for cross-cultural validity, and thus results may need to be viewed with some caution. In addressing this, Rasch analysis can be used to test the psychometric properties of PRO measures to explore cross-cultural validity, and this will ideally be applied in future studies.

Lastly, although response rates were fairly high overall (62%), Arabic participants were less likely to respond to the study invitation, with just under half (49%) agreeing to participate in the study and returning questionnaires. We also noted that those who were male, older, diagnosed with late-stage cancer, and receiving chemotherapy/radiotherapy tended to decline invitations to the study. This may imply that results for Arabic patients may not reflect that of the whole population in this group and that those in active treatment with late-stage disease may also be under-represented.

Most previous reports of cancer disparities in migrants arose spontaneously from research in the general cancer population [7]. This study used rigorous cross-cultural research methods, including the use of bilingual research assistants to increase patient engagement, translation of study material to remove language barriers, and community advisory groups to enhance cultural competence and guide result interpretation. The relatively high proportion of returns (62%) strengthens the broad applicability of our conclusions.

Conclusion

This study documented the extent of cancer disparities regarding psychological issues and quality of life in migrant populations and the determinant role of migrant-specific variables in these outcomes. Intervention programs and practice guidelines aiming to alleviate inequities in existing cancer care services are now required.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Cancer Australia and beyondblue under the Priority-Driven Collaborative Cancer Research Scheme, with some additional financial support provided by Multicultural Health Service, South Eastern Sydney Illawarra Health under the Cultural Diversity Health Enhancement Grants Program. Phyllis Butow holds a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Principal Research Fellowship, Madeleine King is supported by the Australian Government through Cancer Australia, and Afaf Girgis is supported by a Cancer Institute New South Wales grant.

We thank our collaborating clinicians who assisted with access to data and recruitment of participants: Dr. David Goldstein, Dr. Michael Jefford, Dr. Winston Liauw, Dr. Michael Jackson, Dr. Rina Hui, Dr. Martin Tattersall, Dr. Weng Ng, Dr. Ray Asghari, Dr. Christopher Steer, Dr. Janette Vardy, Dr. Phillip Parente, Dr. Marion Harris, Dr. Narayan Karanth, Dr. Michael Friedlander, and Dr. Fran Boyle. We are most grateful to members of our community advisory boards who provided invaluable advice on community engagement, interpretation of data, and study procedures: on the Greek Advisory Board, Nicole Komninou, Father Sophronios Konidaris, Maria Petrohilos, Bill Gonopoulos, Dr. Peter Calligeros, and Elfa Moraitakis; on the Chinese Advisory Board, Wendy Wang, Theresa Chow, Daniel Chan, Viola Yeung, Dr. Agnes Li, Hudson Chen, Dr. Ven Tan, Nancy Tam, Soo See Yeo, and Prof. Richard Chye; and on the Arabic Advisory Board, Father Antonios Kaldas, Mona Saleh, Seham Gerges, and Katya Nicholl. We also thank our bilingual research assistants who assisted with patient recruitment and data translation: Sarah Madah, Suzanne Loway-Aziz, Heba Kassoua, Hala Hubraq, Chen-Yu Huang, Haozhi Jiang, Ren Yi, Cynthis Wang, John Rose, Takis Katsampanis, Evi Drakoulidou, and Eleni Daviskas. Finally we thank all our participants who took part in this study. The Psycho-oncology Co-operative Research Group Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) team also includes Bettina Meiser, Elizabeth Lobb, and Patsy Yates.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Ming Sze, Phyllis Butow, Maurice Eisenbruch, Michael Jefford, Afaf Girgis, Madeleine King, David Goldstein

Provision of study material or patients: Skye Dong, Joshua McGrane, Weng Ng, Ray Asghari, Phillip Parente, Winston Liauw, David Goldstein

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ming Sze, Lisa Vaccaro, Skye Dong

Data analysis and interpretation: Ming Sze, Phyllis Butow, Melanie Bell, David Goldstein

Manuscript writing: Ming Sze

Final approval of manuscript: Ming Sze, Phyllis Butow, Melanie Bell, Lisa Vaccaro, Skye Dong, Maurice Eisenbruch, Michael Jefford, Afaf Girgis, Madeleine King, Joshua McGrane, Weng Ng, Ray Asghari, Phillip Parente, Winston Liauw, David Goldstein

Other (project coordination): Ming Sze

Disclosures

David Goldstein: Bayer, Glaxo, Pfizer (C/A); Celgene (RF, SAB). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Cultural competency in health: A guide for policy, partnerships and participation. Canberra, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health . Human Services, Office of Minority Health: National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. Rockville, MD: IQ Solutions; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . How health systems can address health inequities linked to migration and ethnicity. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butow P, Aldridge L, Bell M, et al. Inferior health-related quality of life and psychological well-being in immigrant cancer survivors: A population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1948–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.2008 Year Book Australia. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, et al. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Greek cancer patients: Psychometric analyses and applicability. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:821–825. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0698-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung CM, Ho S, Kan CS, et al. Evaluation of the Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. A cross-cultural perspective. Int J Psychosom. 1993;40:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonomi AE, Cella DF, Hahn EA, et al. Multilingual translation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) quality of life measurement system. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:309–320. doi: 10.1007/BF00433915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cull A, Sprangers M, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC quality of life group translation procedure. EORTC Brussels; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuman H. The random probe: A technique for evaluating the validity of closed questions. Am Sociol Rev. 1966;31:218–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luckett T, Butow PN, King MT, et al. A review and recommendations for optimal outcome measures of anxiety, depression and general distress in studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adults with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1241–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0932-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pink B. An Introduction to Socio-economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), 2006. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yost KJ, Eton DT. Combining distribution- and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences: The FACIT experience. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:172–191. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy R, Symonds RP, Kumar DM, et al. The use of denial in an ethnically diverse British cancer population: A cross-sectional study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1393–1397. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, et al. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:413–428. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, et al. Cervical cancer survivorship in a population based sample. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pascoe S, Edelman S, Kidman A. Prevalence of psychological distress and use of support services by cancer patients at Sydney hospitals. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:785–791. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, et al. The physical and psycho-social experiences of patients attending an outpatient medical oncology department: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1999;8:73–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1999.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hede K. Agencies look to patient navigators to reduce cancer care disparities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:157–159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw J, Butow P, Sze M, et al. Reducing disparity in outcomes for immigrants with cancer: A qualitative assessment of the feasibility and acceptability of a culturally targeted telephone-based supportive care intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2297–2301. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butow PN, Lobb E, Jefford M, et al. A bridge between cultures: Interpreters’ perspectives of consultations with migrant oncology patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butow P, Bell M, Goldstein D, et al. Grappling with cultural differences; communication between oncologists and immigrant cancer patients with and without interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dein S. Explanatory models of and attitudes towards cancer in different cultures. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:119–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butow PN, Sze M, Dugal-Beri P, et al. From inside the bubble: Migrants’ perceptions of communication with the cancer team. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0817-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]