Abstract

Papillomaviruses (PV) are double stranded (ds) DNA viruses that infect epithelial cells within the skin or mucosa, most often causing benign neoplasms that spontaneously regress. The immune system plays a key role in the defense against PVs. Since these viruses infect keratinocytes, we wanted to investigate the role of the keratinocyte in initiating an immune response to canine papillomavirus-2 (CPV-2) in the dog. Keratinocytes express a variety of pattern recognition receptors (PRR) to distinguish different cutaneous pathogens and initiate an immune response. We examined the mRNA expression patterns for several recently described cytosolic nucleic acid sensing PRRs in canine monolayer keratinocyte cultures using quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Unstimulated normal cells were found to express mRNA for melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA5), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), DNA-dependent activation of interferon regulatory factors, leucine rich repeat flightless interacting protein 1, and interferon inducible gene 16 (IFI16), as well as their adaptor molecules myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88, interferon-β promoter stimulator 1, and endoplasmic reticulum-resident transmembrane protein stimulator of interferon genes. When stimulated with synthetic dsDNA [poly(dA:dT)] or dsRNA [poly(I:C)], keratinocytes responded with increased mRNA expression levels for interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-β, RIG-I, IFI16, and MDA5. There was no detectable increase in mRNA expression, however, in keratinocytes infected with CPV-2. Furthermore, CPV-2-infected keratinocytes stimulated with poly(dA:dT) and poly(I:C) showed similar mRNA expression levels for these gene products when compared with expression levels in uninfected cells. These results suggest that although canine keratinocytes contain functional PRRs that can recognize and respond to dsDNA and dsRNA ligands, they do not appear to recognize or initiate a similar response to CPV-2.

Keywords: Canine papillomavirus, pattern recognition receptors, keratinocyte

1. Introduction

Papillomaviruses (PV) are epitheliotropic, highly species and tissue specific viruses within the family Papillomaviridae. They are circular, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses that contain several early genes (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7) and two late genes (L1 and L2). These viruses are most often associated with benign mucosal and cutaneous epithelial proliferations; however, there are certain high-risk PV types associated with cancer. The immune system plays a key role in controlling these infections and patients with cell mediated immune deficits, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, congenital immune deficiencies, or those on immunosuppressive therapy, are at an increased risk for PV infections and their associated cancers (Doorbar, 2005; Frazer, 2009; zur Hausen, 2009).

Similar observations have been made in dogs with canine papillomavirus-2 (CPV-2), a newly recognized canine PV that is associated with the formation of papillomas on the skin of dogs (Yuan et al., 2007). These viral papillomas are more common in older, immunosuppressed patients and are associated with particularly malignant lesions in a group of dogs with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (Goldschmidt et al., 2006). Normal skin may harbor CPVs, but often these infections remain subclinical in immunocompetent hosts (Lange et al., 2011). It remains unknown, however, if or how the immune system specifically recognizes PV infections and induces an effective antiviral immune response. Since CPV-2 is a cutaneous infection, we were interested in investigating the ability of keratinocytes to upregulate antiviral cytokines, such as type I IFNs, in response to infection with CPV-2.

Keratinocytes are critical members of the immune system and are the first line of defense against invading pathogens in the skin (Suter et al., 2009). The pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their signaling cascades are one way keratinocytes can detect potential pathogens and initiate an antiviral immune response (Tohyama et al., 2005; Lebre et al., 2007; Sugita et al., 2007; Kalali et al., 2008; Miller, 2008; Prens et al., 2008; Hendricks et al., 2012). Viral recognition by these PRRs initiates signaling cascades that lead to the production of type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines, which are important for the elimination of viruses (Barbalat et al., 2011; Rathinam and Fitzgerald, 2011). Viral nucleic acids are recognized by specific PRRs, including certain Toll like receptors (TLR) and cytosolic nucleic acid sensors. TLR9 is the only known TLR that recognizes viral DNA (Barbalat et al., 2011). The cytosolic DNA sensors include DNA-dependent activation of interferon regulatory factors (DAI), leucine rich repeat flightless interacting protein 1 (LRRFIP1), and interferon inducible gene 16 (IFI16) (Rathinam and Fitzgerald, 2011). The cytosolic RIG-I like helicases (RLR), which include melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA5) and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), recognize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which can be synthesized during infection with a DNA virus (Matsumiya et al., 2011). Signaling through these different receptors requires specific adaptor molecules that activate transcription factors to induce expression of antiviral cytokines. TLR9 signals through the adaptor molecule myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) (Barbalat et al., 2011). The RLRs require the adaptor protein IFN-β promoter stimulator 1 (IPS-1) and the DNA sensors DAI and IFI16 require the adaptor molecule endoplasmic reticulum-resident transmembrane protein stimulator of IFN genes (STING) (Matsumiya et al., 2011; Rathinam and Fitzgerald, 2011).

Natural infection with PVs requires a break in the stratified squamous epithelium and exposure of basal keratinocytes to infectious particles (Doorbar, 2005). In these basal keratinocytes, the genome is maintained at low copy numbers with expression of early viral genes (Doorbar, 2005). The proliferative phase, genome amplification, and virus synthesis occurs after basal cells have exited the cell cycle and undergone terminal differentiation (Doorbar, 2005). Infection of primary canine keratinocyte cultures in our study was used to mimic the initial infection of basal epithelial cells.

The first objective of this study was to determine if canine keratinocytes express mRNA for these DNA and RNA sensing PRRs by establishing a quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay to characterize their expression patterns in keratinocytes in response to different PRR ligands. Our second objective was to examine the mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines, type I IFNs, and these DNA and RNA sensing PRRs in keratinocytes after infection with CPV-2. We found that CPV-2 infection does not induce transcriptional activation of antiviral cytokines or interferon responsive genes (IRGs), suggesting that CPV-2 successfully evades innate immune recognition early in infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 CPV-2 virus propagation, purification, and quantification

CPV-2 was propagated and purified using a modified mouse xenograft system as previously described (Yuan et al., 2007). In brief, fresh dog buccal mucosa was incubated with papilloma homogenate for 2 hours, and then implanted subcutaneously in three SCID mice. Twelve weeks later, the mice were sacrificed and the grafts were collected. The tissue was cut into small pieces and homogenized in extraction buffer (0.02 M Tris, pH 7.5, 1.0 M NaCl, 30 μM PMSF) using a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 16,000 rcf for 30 minutes at 4 °C using an HB-4 rotor (Sorvall centrifuge, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA). The supernatant (about 3 ml) was transferred to a Ti centrifugation tube and ultracentrifuged at 4 °C, 126,000 rcf for 101 min (70 Ti rotor, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). The pellet was resuspended in a total of 20 ml of CsCl (D = 1.333) using a Dounce homogenizer. The CsCl solution (5 ml each tube) was then centrifuged at 110,000 rcf for 20 hours (55 Ti rotor, Beckman Coulter) at 4 °C. The band containing virions was aspirated from the side of the centrifuge tube with a 3 ml syringe (23 gauge needle) and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline containing phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride overnight at 4 °C. Viral genomic DNA was quantified using qPCR. SYBR Green real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was performed on the Bio-Rad iCycler MyiQ (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) for quantification of viral E6 DNA. The primers used to detect E6 were: sense primer, 5′-TGCTACGTGTACTGTTGAAGG-3′, anti-sense primer, 5-ACTAGCATAAATGGCGACCG-3′. A standard curve using a plasmid containing CPV-2 genome was established for the quantification. Primer concentration in the reaction mixture was 5 pmol/ml. Cycling conditions were 95° for 10 min followed by 42 cycles of 94° for 15 s and 60° for 1 min. All samples were run in triplicate. The quantity of viral genomic DNA was determined using iQ™5 Optical System Software (BioRad).

2.2. Isolation of keratinocytes, ligand stimulation, and CPV-2 infection

Skin samples were obtained from discarded fresh biopsy samples from dogs without a history of skin disease submitted to the anatomic pathology service at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital at the University of California, Davis. Samples were collected under the approval of the UC Davis Clinical Trial Review Board for tissue banking samples and use for non-invasive procedures with a general owner consent form. Primary canine keratinocyte cultures were established based upon previously published protocols (Suter et al., 1991; Kolly et al., 2005). In brief, the sections of skin were placed immediately into canine keratinocyte culture media CnT-09 (CELLnTEC advanced cell systems AG, Bern, Switzerland) supplemented with 100 U/ml Penicillin, 100 μg/ml Streptomycin and 250 ng/ml Amphotericin B (CnT-ABM, CELLnTEC advanced cell systems AG). The epidermis was then separated from the dermis after incubation in 10 mg/ml dispase II neutral protease, grade III (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The epidermis was then placed in TrypLE for 30 minutes (Gibco Invitrogen Cell Culture, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to obtain a single cell suspension, which was then incubated at 34° C and 5% CO2, as previously described.

For all stimulation/infection assays, 3.0 × 105 viable keratinocytes (between passage 3-10) were seeded into multiple wells of 6-well tissue culture plates (Fischer Scientific, BD Falcon, Hanover Park, IL, USA) and incubated at 34° C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours. After 24 hours, the cells were either incubated in medium alone or medium containing 0.6μg/ml poly(dA:dT)/Lyovec (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA), 0.5μg/ml poly(I:C) (Invivogen), 2μg/ml E.coli ssDNA/LyoVec (Invivogen), or 20, 100, or 200 CPV-2 particles per cell. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated in at least three independent experiments using primary keratinocyte cultures derived from at least 3 individual normal control dogs. Since PVs are non-cytolytic viruses and do not produce virions in monolayer cultures, confirmation of in vitro PV infection is most commonly based upon the presence of mRNA spliced transcripts of the viral early genes (Ozbun, 2002). In this study, we performed RT-PCR to detect transcription of the early viral gene E2 and the spliced transcripts E1^E4 and E1^E2. Primers for E2 were designed based upon the published genome sequence for CPV-2 and are listed in Table 1. Primers for E1^E4 and E1^E2 were designed based upon identification of splice sites between E1 and E2 and between E1 and E4 (Yuan H., manuscript in preparation); primer pairs are listed in Table 1. PCR reaction conditions are listed below. The cells were incubated at 34° C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours after stimulation/infection and then lyzed for RNA extraction. For viral infection and subsequent ligand stimulation, the cells were incubated with 200 CPV-2 particles per cell or medium alone for four days and either 0.6μg/ml poly(dA:dT), 0.6μg/ml Poly(I:C) or medium alone was added to appropriate wells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate using keratinocytes derived from one dog; the experiment was repeated in two additional independent experiments using keratinocytes derived from two additional dogs. The cells were incubated at 34° C and 5% CO2 for an additional 2 days before the cells were lyzed for RNA extraction.

Table 1.

Primer sets, product size, and GenBank accession numbers for RT-PCR.

| Target gene | GenBank accession no. | Primer sequence forward and reverse (5'-- 3') | Product size (bp) | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRRFIP1 | XM_534615.3 | GAGTGACCGAGACGATCTTAG | 97 | 105 |

| CCCGTTGGTAGCTATG | ||||

| DAIa | XM_849539.3 | GGAGGTGCCAGCAAGACATAG | 153/327 | ND |

| AAATGTGGTTATGTGGTCCGT | ||||

| DAIb | XM_849539.3 | TCACTGACCAGCATTCGAGAG | 99 | 102 |

| TGTGGTTATGTGGTCCGTT | ||||

| MDA5 | XM_545493.3 | GGAGAAGAAGCTGCTGACCGA | 161 | 102 |

| GGGCATAGTTCTCCGTTTGA | ||||

| RIG-I | XM_003639385.1 | AGAAGGCTGGTTCCGTG | 146 | 91.5 |

| TAAATTCTGGTTGTAAACGCT | ||||

| IFI16 | XM_003434299.1 | ACTCCAAAAATCCGTGATCT | 154 | 102 |

| GGCGTCCATACACCCA | ||||

| MyD88 | XM_003433106.1 | CGGATGGTAGTGGTTGTCT | 113 | 108 |

| TCTTCATTGCCTTGTACTTG | ||||

| IPS-1 | XM_001122609.1 | CCAGCGGAGCCACAGTTAGT | 90 | 99 |

| CTCTCTGTAGCCGTTGGTG | ||||

| STING | XM_843245.2 | CCGCCTCATTGTCTACCA | 109 | 99 |

| CATGCTGCCCATAGTAACCTC | ||||

| IFN-k | XM_003639384.1 | TGGAAGAGGATGGGATAAAC | 149 | 108 |

| TCTGATTTCCACTCGGATG | ||||

| E1^E2a | NC_006564.1 | AAGAGCACTTCAGCGATG | 163 | ND |

| TTGCTGCCAGACTCATACTGA | ||||

| E1^E4a | NC_006564.1 | CCGAAGGAGGTGAAAGAGCGT | 122 | ND |

| CTTTTCGCCATCCTCATCTGTATA | ||||

| E2a | NC_006564.1 | GTGGGCCTATATTTACTATCA | 139 | ND |

| GCGCAGAGCATCCTTAGCA |

primer pair used for conventional PCR only

primer pair used for real time PCR; sense primer spans exon 3-exon 5 junction and was based upon 153bp sequence derived with first set of DAI primers

ND= not done; primers only used for conventional PCR

2.3 Total RNA extraction and cDNA preparation

Total RNA was isolated using a RNA extraction kit (Qiagen RNeasy mini kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following manufactures recommended protocol. Resulting RNA was subsequently DNase treated to eliminate contaminating DNA and complementary DNA (cDNA) generated utilizing a reverse transcription kit (Quantitec RT kit, Qiagen). A sample without reverse transcriptase was used to control for genomic DNA contamination.

2.4 Primer design and validation

Primers for canine IFN-κ, DAI (also known as Z-DNA binding protein 1), LRRFIP1, IFI16 (canine homolog of human IFI16 identified as interferon activable protein 203), RIG-I (also known as ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX-58), MyD88, IPS-1 (also known as mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein), STING (also known as transmembrane protein 173), and MDA5 (also known as interferon induced with helicase C domain 1) were designed based upon the reference mRNA sequences listed in the NCBI database using commercially available primer design software (Oligo Primer Analysis Software, Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., West Cascade, CO, USA). Sequences of primer pairs and the reference mRNA sequences are listed in Table 1. Primer sets used for GAPDH were provided by the UC Davis Real-time Research and Diagnostics Core Facility (Davis, CA) and are as follows: forward 5’ (TCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACC) 3’; reverse 5’ (ACCTTGCCCACAGCCTTG) 3’. Conventional PCR followed by sequence analysis was performed to validate the primer pairs. To this aim, the cDNA sample (10ul of 1:10 dilution) was amplified by PCR in a reaction mixture (40 μl) containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 200uM each (800 μM) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1 unit (0.2 μl) taq polymerase, and approximately 0.5 μg of each primer for a total reaction volume of 50 μl. All PCR reactions were performed on an Applied Biosystems GeneAmp PCR system 2700 thermocycler (Foster City, CA, USA). An initial step of 95° C for 10 minutes (HotStar Taq DNA polymerase, Qiagen, Valencia, CA., USA) was followed by 40 cycles of 1) 1 minute at 95° C 2) 1 minute at 55° C, and 3) 1 minute at 72° C and concluded with a final step of 72° C for 10 minutes. All PCR products were electrophoresed through 1.5% agarose at 80 V for two hours and stained with Cyber Gold (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 minutes. The PCR products were purified using Promega Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol and submitted for DNA sequencing (University of California, Davis, CA, USA). To confirm CPV-2 infection, PCR products for E1^E2, E1^E4, E2, and GAPDH were size separated and visualized using an eGene HDA-GT12 capillary electrophoresis analyzer (renamed QIAxcel, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

2.5 RT-qPCR

Two different sized PCR products for DAI were obtained using the first set of primers listed for DAI in Table 1. The 327 bp product, which included a portion of exon 3, all of exon 4, and a portion of exon 5, was identical to the nucleotide sequence listed in the NCBI database. The 153bp product included a portion of exon 3 and exon 5 but was missing exon 4. This 153bp nucleotide sequence was used to design the DAI primer pair used for RT-qPCR; the sense primer crosses the exon 3/ exon 5 junction.

Real time RT-PCR for IFN-κ, DAI, LRRFIP, IFI16, RIG-I, MDA5, MyD88, STING, and IPS-1 was performed using SYBR green detection (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following standard protocols. Briefly, 10μl of diluted cDNA (1:10) was added to a master mix containing 12.5μl of SYBR Green master mix, 0.5 to 1μl each of forward and reverse primers, and 0.5 to 1.5 μl of water to yield a total PCR mix of 25ul. The Validated Taqman® Gene Expression Assay system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for the following primer and probe sets: β-actin (Cf03023880_g1), IFN-β (Cf03644503_s1), IL-6 (Cf02624282_m1), TNF-α (Cf02628237_m1), and TLR9 (Cf02717353_g1) following their recommended protocols. Briefly, all reactions were set up in a 20μl reaction mix in optical 96 well plates using Taqman Universal Primer Mix (Applied Biosystems). The reaction mix consisted of 10μl 2X master mix, 1μl primer/probe mix, and 9μl of cDNA (diluted 1:10). All PCR reactions were performed on a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Reaction conditions for SYBR green detection were as follows: 95° C for 15 minutes followed by 40 cycles of 94° C for 30s, 57° C for 30s, and 72° C for 31s, and a final phase at 72° C for 10 minutes. Product specificity was monitored by a final melting curve analysis. Assays were validated using standard curves generated with serial fold dilutions of cDNA template; primer efficiencies are listed in Table 1. Reaction conditions for taqman detection were as above except the annealing temperature was changed to 60° C. For baseline expression of PRRs, individual genes were normalized to expression of GAPDH and graphed as the ΔCq value. For stimulation assays, the expression of individual genes was normalized to expression of GAPDH (Sybr green detection method) or β-actin (taqman detection method) and graphed as the relative fold change between the experimental (stimulated/infected) and calibrator (un-stimulated sample) based upon the 2-ΔΔCq method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

2.7 Statistics

Statistical analysis and graphical presentation were performed using Graph Pad Prism 4 software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA). Mean values for relative gene expression were compared between unstimulated samples and samples stimulated with either poly(dA:dT), poly(I:C), or CPV-2 using the Mann-Whitney U-test. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1 Cultured canine keratinocytes express mRNA for the DNA sensing PRRs and adaptor molecules

All primer pairs successfully amplified cDNA for canine IFN-κ, MDA5, RIG-I, IFI16, LRRFIP-1, DAI, IPS-I, STING, and MyD88, which were confirmed by sequence analysis of the PCR products.

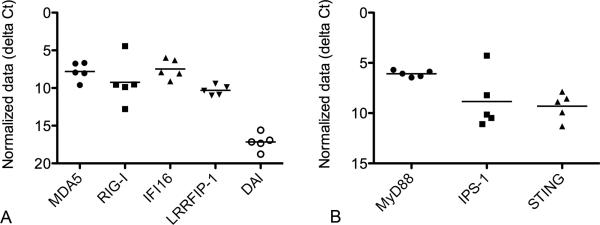

Canine keratinocytes derived from 5 different dogs were cultured in duplicate for 24 hours and baseline mRNA expression of PRRs and adaptor molecules was analyzed by RT-qPCR. Canine keratinocytes expressed mRNA for all DNA sensing PRRs and adaptor molecules analyzed (Figure 1). Of the cytosolic nucleic acid sensing PRRs investigated, the relative transcription level at baseline for DAI was lower (higher Cq) than the other receptors examined.

Fig. 1.

Baseline mRNA expression of cytosolic nucleic acid sensing pattern recognition receptor (a) and adaptor molecule (b) mRNA expression in normal canine monolayer keratinocyte cultures at 24 hours (n=5). Expression is graphed as the cycle number (Cq) normalized to the reference gene, GAPDH (ΔCq). Graph y-axis is reversed so higher Cq values, which correspond to lower expression, are placed lower on the graph. Bar designates mean expression.

3.2 Keratinocytes respond to dsDNA ligand by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines, type 1 IFNs, and cytosolic nucleic acid sensing PRRs

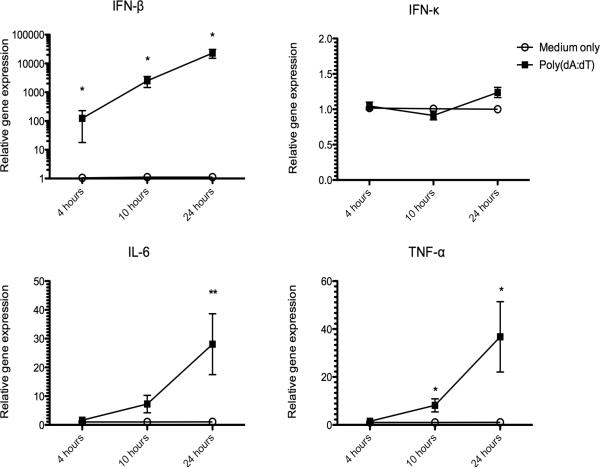

Canine keratinocytes derived from 5 different dogs were cultured in duplicate for 24 hours and then stimulated with poly(dA:dT) for an additional 4, 10, or 24 hours. The keratinocytes upregulated mRNA transcription for IFN-β, IL-6, and TNF-α in response to stimulation with poly(dA:dT) (Figure 2). In the time frame analyzed, the highest transcription was detected 24 hours post-stimulation for IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-β. Gene transcription for IFN-β revealed the largest fold increase of all the cytokines analyzed. There was no significant fold change in the mRNA expression of IFN-κ between unstimulated and stimulated keratinocytes.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of cytokine mRNA expression in canine cultured keratinocytes stimulated with the synthetic double stranded DNA ligand poly(dA:dT). Cytokine mRNA expression was determined at 4, 10, and 24 hours after stimulation with poly(dA:dT) by quantitative RT-PCR. Resulting Cq values were normalized to the Cq value of reference gene and calibrated to mRNA expression in unstimulated keratinocytes (ΔΔCq). Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated in at least three independent experiments using primary keratinocyte cultures derived from 5 individual normal dogs. Results expressed as mean +/− SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (Comparison with medium only control; Mann-Whitney U test)

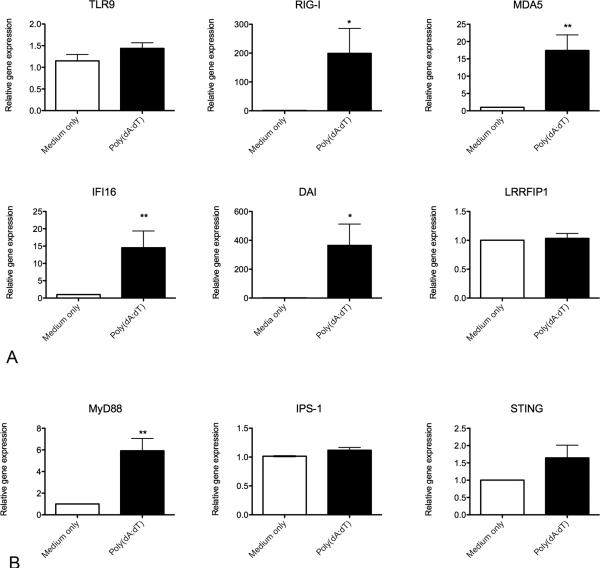

Several of the PRRs are IRGs and can be upregulated in response to viral infections. Of the nucleic acid sensing PRRs, gene transcription for DAI, RIG-I, MDA5, and IFI16 was significantly increased in the stimulated cells when compared to unstimulated cells at 24 hours (Figure 3A). The greatest fold increase over expression in unstimulated cells was for DAI and RIG-I. There was no significant increase in gene transcription for LRRFIP1 or TLR9. Gene transcription for MyD88 was significantly increased in stimulated cells when compared with unstimulated cells (Figure 3B). No significant increase in gene transcription of STING or IPS-I was identified.

Fig. 3.

Nucleic acid sensing pattern recognition receptor (a) and adaptor molecule (b) mRNA expression in canine keratinocytes stimulated with the synthetic double stranded DNA ligand poly(dA:dT) for 24 hours. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated in at least three independent experiments using primary keratinocyte cultures derived from 5 individual normal dogs. Results expressed as mean +/− SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (Comparison with medium only control; Mann-Whitney U test)

3.3 CPV-2 infection of canine keratinocytes does not initiate upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, type I IFNs, or cytosolic nucleic acid sensing PRRs

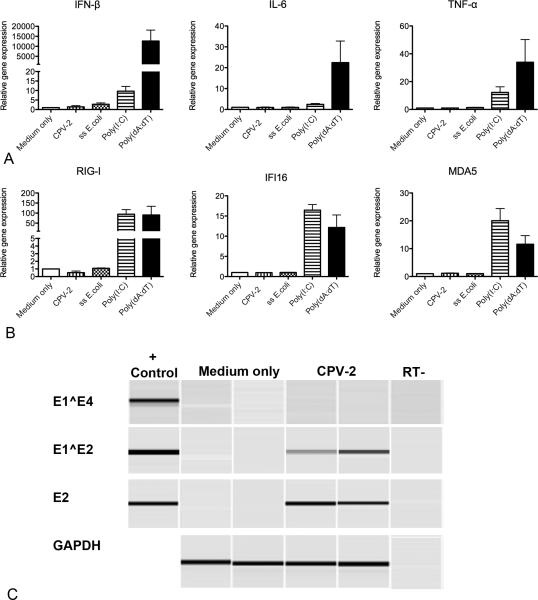

Since we had shown that keratinocytes were able to elicit an immune response to synthetic dsDNA, we next wanted to determine if keratinocytes were able to elicit an immune response to CPV-2, dsRNA poly(I:C), and a TLR9 ligand (ssE.coli). Canine keratinocytes derived from 3 different dogs were cultured in duplicate for 24 hours and then stimulated with either CPV-2, poly(dA:dT), Poly(I:C), or ssE.coli for an additional 24 hours. Stimulation with poly(I:C) resulted in upregulation of IFN-β, IL-6, TNF-α, RIG-I, MDA5, and IFI16 after 24 hours when compared with unstimulated cells (Figure 4A and B). No significant upregulation of the proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α), IFN-β, or the PRRs IFI16, MDA5, and RIG-I was identified with infection using 100 CPV-2 viral particles per cell or the TLR9 ligand ssE.coli. The TLR9 ligand ssE.coli was shown to upregulate proinflammatory cytokines in a canine dendritic cell line (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Cytokine (a) and pattern recognition receptor (PRR) (b) mRNA expression in canine keratinocytes stimulated with 100 canine papillomavirus -2 (CPV-2) viral particles, sheared ss E.coli, poly(I:C), or poly(dA:dT) for 24 hours. 4a and b. mRNA expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated in three independent experiments using primary keratinocytes cultures derived from three individual normal dogs. 4c. RT-PCR for the CPV-2 spliced transcripts E1^E2 and E1^E4, early gene E2, and internal control (GAPDH) in non-infected and CPV-2 infected keratinocytes. Results are shown from one of three experiments. Similar results were obtained for E1^E4, E2, and GAPDH in all three experiments. Only one experiment out of three detected E1^E2 expression in the infected keratinocytes.

E1^E4 spliced transcripts are most commonly used for PV infectivity assays (Ozbun, 2002); however, these splice transcripts were not detected within the keratinocytes after 24 hours of infection (Figure 4C). Detection of E1^E2 splice transcripts was present consistently in only one out of the three replicate experiments while a portion of the E2 gene was detected consistently in all three replicate experiments. The internal control gene (GAPDH) was detected within all samples. We also infected keratinocytes with 20, 100, and 200 CPV-2 particles per cell for 6 days with no detectable upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, type I inteferons, or PRRs (data not shown); CPV-2 infection was confirmed in these keratinocytes by RT-PCR detection of spliced transcripts E1^E2 which were expressed in all replicates and repeated experiments.

3.4 CPV-2 infected keratinocytes can upregulate proinflammatory cytokines, type I inteferons, and PRRs when stimulated with dsDNA and dsRNA ligands

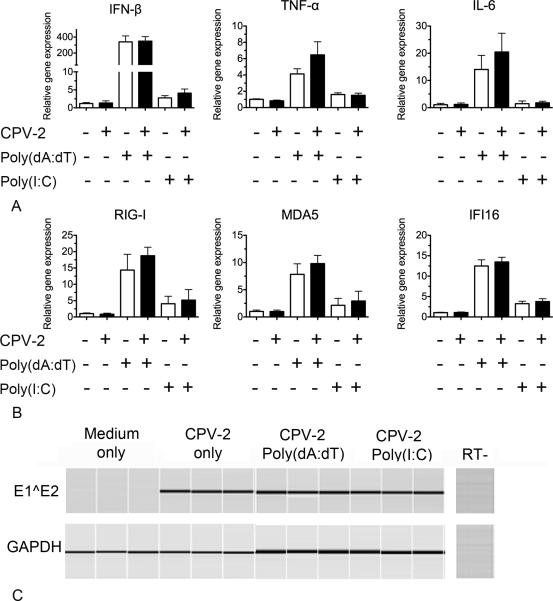

PVs have evolved many different mechanisms to evade the host immune system (Stanley, 2012). Several of the early proteins, E6 and E7, have been shown to bind to and inhibit IFN regulatory factors, which are important for the upregulation of cytokines elicited by PRRs [reviewed in (Karim et al., 2011; Stanley, 2012)]. We wanted to determine if CPV-2 infection of keratinocytes prevented the upregulation of gene transcription for proinflammatory cytokines when stimulated with two different PRR ligands. Canine keratinocytes derived from 3 different dogs were cultured in triplicate for 24 hours and then infected with CPV-2. At 4 days post infection, the keratinocytes were stimulated with either poly(I:C) or poly(dA:dT) for an additional 48 hours. We found no significant differences in mRNA transcription for cytokines or PRRs between uninfected and CPV-2 infected cells when stimulated with either poly(dA:dT) or poly(I:C) (Figure 5A and 5B). E1^E2 transcripts were detected in all replicates and independent experiments by conventional RT-PCR in the CPV-2 infected keratinocytes (Figure 5C). Conventional PCR for GAPDH was performed as an internal control gene (Figure 5C).

Fig. 5.

Cytokine and pattern recognition receptor (PRR) mRNA expression in canine keratinocytes infected with canine papillomavirus-2 (CPV-2) for 4 days and then stimulated with poly(dA:dT) or poly(I:C) for an additional 48 hours. 5a and b. mRNA expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated in three independent experiments using keratinocyte cultures derived from three individual normal dogs. Results expressed as mean +/− SEM. 5c. RT-PCR for the CPV-2 spliced transcripts E1^E2 and internal control (GAPDH) in non-infected and infected keratinocytes. Results are shown from one of three experiments performed in triplicate with similar results.

4. Discussion

We were able to demonstrate in this study that canine keratinocytes express nucleic acid sensing PRRs that recognize dsDNA and induce upregulation of antiviral cytokines and IRGs. PVs are potentially exposed to these nucleic acid sensing PRRs in the early phase of infection during viral entry, release from the viral capsid and transit to the nucleus, viral replication, and transcription of viral genes (Sapp and Bienkowska-Haba, 2009) (Doorbar, 2005). When infected with CPV-2, however, there was no similar upregulation of antiviral cytokines or IRGs, suggesting that this PV is able to avoid recognition by these nucleic acid sensors.

PVs enter keratinocytes through receptor-mediated endocytosis where they are potentially exposed to TLR9 within the endosome (Sapp and Bienkowska-Haba, 2009). A TLR9 ligand, however, did not elicit upregulation of antiviral cytokines or IRGs in these canine keratinocytes. The lack of cytokine and IRGs response to CPV-2 may therefore reflect an inactive TLR9 pathway and not an immune evasion strategy by the virus. This is in contrast to other studies that have detected increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in response to TLR9 agonists in human keratinocytes (Lebre et al., 2007; Sugita et al., 2007). It is possible that we may detect a response to the TLR9 ligand at a different time point or by examining different cytokines or chemokines.

Despite several potential stages where PV-derived nucleic acids could be exposed to the cytosolic PRRs, we did not detect any upregulation of antiviral cytokines or IRGs after viral infection. The PV life cycle itself could partially account for this finding. In the initial stage of infection of basal keratinocytes, the viral genome is maintained at low numbers, between 50-100 copies per cell, and only the very early genes are transcribed, thereby limiting the potential exposure of their virally derived nucleic acid to PRRs (Stanley, 2012). Vegetative viral replication and expression of the immunogenic capsid protein is restricted to the terminally differentiated cells which are not represented in monolayer cultures (Doorbar, 2005). Other DNA viruses evade recognition by encoding specific proteins that destroy the dsRNA viral agonists that would stimulate the PRRs (Paludan et al., 2011). It is unknown currently if PVs induce a similar dsRNA intermediate and how it avoids detection by the RLRs.

Other immune evasion strategies of PVs include interfering with and inhibiting critical molecules within the signaling pathways of the PRRs and type I IFNs (reviewed in (Stanley, 2012)). This is accomplished by either of the oncoproteins, E6 and/or E7, binding to critical molecules within the PRR or IFN pathways, which results in diminished cytokine and IRG production in response to PRR stimulation (Nees et al., 2001) (Karim et al., 2011) (Reiser et al., 2011). We, however, found that there was no difference in the response to synthetic dsDNA and dsRNA ligands between uninfected and CPV-2 infected keratinocytes. This suggested that the PRR and type I IFN signaling pathways were functional in these infected keratinocytes. Unlike the other studies using E6 and/or E7 expressing cell lines, our experiment mimics infection of the basal keratinocytes where expression of the E6 and E7 genes is minimal (Nees et al., 2001; Stanley, 2012). Alternatively, the ability of PV oncogenes to inhibit these signaling pathways is type specific and it may be that the CPV-2 oncogenes do not inhibit or interfere with the PRR or IFN signaling pathways at any stage of infection. Experiments using cell lines expressing the CPV-2 oncogenes E6 and E7 may help to differentiate these possibilities.

The transcription of the viral genes is tightly controlled and is dependent on the stage of differentiation of the keratinocyte (Doorbar, 2005). In basal keratinocytes, the early genes E1, E2, E6, and E7 are expressed, albeit at low levels (Doorbar, 2005). We were unable to detect the E1^E4 spliced transcripts and inconsistently detected the E1^E2 spliced transcripts 24 hours post infection. The E1^E4 spliced transcript encodes the viral protein E4; however, this protein is often not expressed until the kerationcytes are terminally differentiated (Roberts, 2006). It is likely that the kerationcytes in our monolayer cultures are not terminally differentiated and do not express E4. Detection of E1^E2 was variable at 24 hours but consistent after 2 days post infection, suggesting that this spliced transcript is produced early in infection but may be somewhat dependent on differentiation state of the keratinocyte. Proliferating keratinocytes in culture begin to terminally differentiate as they reach confluency, which could stimulate expression of some of the early viral genes (Kolly et al., 2005). Since the time to reach confluency may be influenced by cell line, passage number, or growth rate of the cells, we thought that this was a likely cause for the inter-experimental variation in detection of E1^E2 transcripts at 24 hours. After 2 days post infection, the E1^E2 transcripts are consistently detected and are a good method to confirm CPV-2 infection in cultured cells.

In conclusion, despite successfully infecting canine keratinocytes, we did not detect any alterations in mRNA transcripts for any of the cytokines or PRRs examined, suggesting that the virus successfully evades immune recognition.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by grant number T32 RR07038 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was also made possible by the Center for Companion Animal Health, University of California, Davis through grant (2011-14-F).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work.

References

- Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, Barton GM. Nucleic acid recognition by the innate immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:185–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorbar J. The papillomavirus life cycle. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):S7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer IH. Interaction of human papillomaviruses with the host immune system: a well evolved relationship. Virology. 2009;384:410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt MH, Kennedy JS, Kennedy DR, Yuan H, Holt DE, Casal ML, Traas AM, Mauldin EA, Moore PF, Henthorn PS, Hartnett BJ, Weinberg KI, Schlegel R, Felsburg PJ. Severe papillomavirus infection progressing to metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in bone marrow-transplanted X-linked SCID dogs. J Virol. 2006;80:6621–6628. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02571-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks A, Elson-Riggins JG, Riddle AL, House AK, Varjonen K, Bond R. Ciclosporin modulates the responses of canine progenitor epidermal keratinocytes (CPEK) to toll-like receptor agonists. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012;147:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalali BN, Kollisch G, Mages J, Muller T, Bauer S, Wagner H, Ring J, Lang R, Mempel M, Ollert M. Double-stranded RNA induces an antiviral defense status in epidermal keratinocytes through TLR3-, PKR-, and MDA5/RIGI-mediated differential signaling. J Immunol. 2008;181:2694–2704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim R, Meyers C, Backendorf C, Ludigs K, Offringa R, van Ommen GJ, Melief CJ, van der Burg SH, Boer JM. Human papillomavirus deregulates the response of a cellular network comprising of chemotactic and proinflammatory genes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolly C, Suter MM, Muller EJ. Proliferation, cell cycle exit, and onset of terminal differentiation in cultured keratinocytes: pre-programmed pathways in control of C-Myc and Notch1 prevail over extracellular calcium signals. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1014–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CE, Zollinger S, Tobler K, Ackermann M, Favrot C. Clinically healthy skin of dogs is a potential reservoir for canine papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:707–709. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebre MC, van der Aar AM, van Baarsen L, van Capel TM, Schuitemaker JH, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC. Human keratinocytes express functional Toll-like receptor 3, 4, 5, and 9. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:331–341. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumiya T, Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Satoh K. Antiviral signaling through retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like receptors. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2011;59:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00005-010-0107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS. Toll-like receptors in skin. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:71–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yadr.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nees M, Geoghegan JM, Hyman T, Frank S, Miller L, Woodworth CD. Papillomavirus type 16 oncogenes downregulate expression of interferon-responsive genes and upregulate proliferation-associated and NF-kappaB-responsive genes in cervical keratinocytes. J Virol. 2001;75:4283–4296. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4283-4296.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbun MA. Infectious human papillomavirus type 31b: purification and infection of an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2753–2763. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-11-2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paludan SR, Bowie AG, Horan KA, Fitzgerald KA. Recognition of herpesviruses by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:143–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prens EP, Kant M, van Dijk G, van der Wel LI, Mourits S, van der Fits L. IFN-alpha enhances poly-IC responses in human keratinocytes by inducing expression of cytosolic innate RNA receptors: relevance for psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:932–938. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam VA, Fitzgerald KA. Innate immune sensing of DNA viruses. Virology. 2011;411:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser J, Hurst J, Voges M, Krauss P, Munch P, Iftner T, Stubenrauch F. High-risk human papillomaviruses repress constitutive kappa interferon transcription via E6 to prevent pathogen recognition receptor and antiviral-gene expression. J Virol. 2011;85:11372–11380. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05279-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. The E4 protein-- A late starter. In: Campo MS, editor. Papillomavirus research from natural history to vaccines and beyond. Caister Academic Press; Norfolk England: 2006. pp. 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sapp M, Bienkowska-Haba M. Viral entry mechanisms: human papillomavirus and a long journey from extracellular matrix to the nucleus. Febs J. 2009;276:7206–7216. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA. Epithelial cell responses to infection with human papillomavirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:215–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05028-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita K, Kabashima K, Atarashi K, Shimauchi T, Kobayashi M, Tokura Y. Innate immunity mediated by epidermal keratinocytes promotes acquired immunity involving Langerhans cells and T cells in the skin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:176–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter MM, Pantano DM, Flanders JA, Augustin-Voss HG, Dougherty EP, Varvayanis M. Comparison of growth and differentiation of normal and neoplastic canine keratinocyte cultures. Vet Pathol. 1991;28:131–138. doi: 10.1177/030098589102800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter MM, Schulze K, Bergman W, Welle M, Roosje P, Muller EJ. The keratinocyte in epidermal renewal and defence. Vet Dermatol. 2009;20:515–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2009.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohyama M, Dai X, Sayama K, Yamasaki K, Shirakata Y, Hanakawa Y, Tokumaru S, Yahata Y, Yang L, Nagai H, Takashima A, Hashimoto K. dsRNA-mediated innate immunity of epidermal keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Ghim S, Newsome J, Apolinario T, Olcese V, Martin M, Delius H, Felsburg P, Jenson B, Schlegel R. An epidermotropic canine papillomavirus with malignant potential contains an E5 gene and establishes a unique genus. Virology. 2007;359:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers - a brief historical account. Virology. 2009;384:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]