Abstract

In the fatty acid biosynthesis of plants and bacteria, the acyl carrier protein (ACP) is known to sequester elongating products within its hydrophobic core, but this dynamic mechanism remains poorly understood. In this paper we exploit solvatochromic pantetheine probes attached to ACP that fluoresce when sequestered. Addition of a catalytic partner lures the cargo out of the ACP and into the active site of the enzyme, enhancing fluorescence to reveal the elusive chain-flipping mechanism. This activity is confirmed by demonstration of a dual solvatochromic-crosslinking probe and solution-phase NMR. The chain-flipping mechanism can be visualized by single molecule fluorescent techniques, demonstrating specificity between the Escherichia coli ACP and its ketoacyl synthase catalytic partner KASII.

Keywords: solvatochromism, acyl carrier protein, chain-flipping mechanism, fatty acid synthase, fatty acids

Primary and secondary acetate metabolites are synthesized by dedicated fatty acid and polyketide synthases. Both families are subdivided in type I and type II architectures, based on whether they are encoded on one multidomain polypeptide chain or as separate proteins, respectively. These are often represented as molecular assembly lines with domains that perform chemistry on the growing metabolite while tethered to an acyl carrier protein (ACP),[1] which shuttles its cargo from one enzyme to the next. Although synthetic biologists have ambition to swap domains and modules between these synthases to create new molecular architectures, these efforts have been tempered by the discovery that both protein-substrate and protein-protein interactions play an important role in both iterative and modular assemblies.[2] Due to the highly dynamic nature of these protein complexes, structural information on their interactions remains scarce.

Productive interactions between the ACP and its partners are required for catalysis, and de novo design of synthases will rely on this underlying behavior. The large ACP family (>100,000 homologs) is structurally conserved in all kingdoms of life and spans a large sequence space.[3] All ACPs are acidic proteins of 60–100 amino acids, and contain three major and one small α-helix. A highly conserved serine motif (D/W/N-S-L/M) is post-translationally modified by phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTases) that transform apo-ACP into its holo form by addition of the phosphopantetheine moiety from coenzyme A (CoA), the terminal thiol of which ferries cargo during catalysis via a thioester linkage.

In type II synthases, where enzymes are found as separate proteins, NMR[4] and molecular dynamic studies[5] have demonstrated that cargo becomes sequestered in the ACP hydrophobic core between helix II and III. In contrast, type I synthases do not appear to sequester their cargo.[6] At least four different explanations have been proposed for cargo sequestration, including protecting the thioester linkage from hydrolysis and premature product release, protecting unstable polyketides from side-reactions, providing a limiting “ruler” for control of metabolite size, and inducing conformational changes to trigger proper catalysis.

Here we provide a new technique to visualize cargo sequestration and release by ACPs and catalytic partners using solvatochromic fluorophores (Fig. 1). These dyes are highly sensitive to environment, displaying different fluorescence lifetimes, emission wavelengths and quantum yields that vary with solvent hydrophobicity.[7] Solvatochromic dyes[8] have successfully found important application in protein structure and dynamics studies,[7b] and we recognized the potential utility of such environmental reporters as a tag to probe ACP activity.[9] 4-N,N-dimethylamino-1,8-napthalimide (4-DMN), recently applied to protein-peptide-interaction sensing,[10] displays only weak fluorescence in aqueous solution, making it ideal for detecting small environmental changes.[7a] 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl (Nbd)[11] derivatives also show solvatochromic behavior but differ in electronic and steric properties. These dyes along with rhodamine B, which is much larger and shows limited solvatochromic behavior,[12] were fused with pantetheine analogs for attachment to ACP (Fig. 2). Computational docking predicted that the Nbd- and 4-DMN pantetheine analogs would be able to sequester into the core of type II FAS ACPs (see SI Discussion and Table S1, Table S2, Fig. S1 and Fig. S2), but the larger rhodamine pantetheine analog would not show sequestration. No probe was predicted to sequester in type I FAS ACPs. Although these solvatochromic probes do not resemble the natural fatty acid cargo of ACPs, computational docking shows that especially small dyes, like 4-DMN, do fit in the inner core of ACPs of type II FASs.

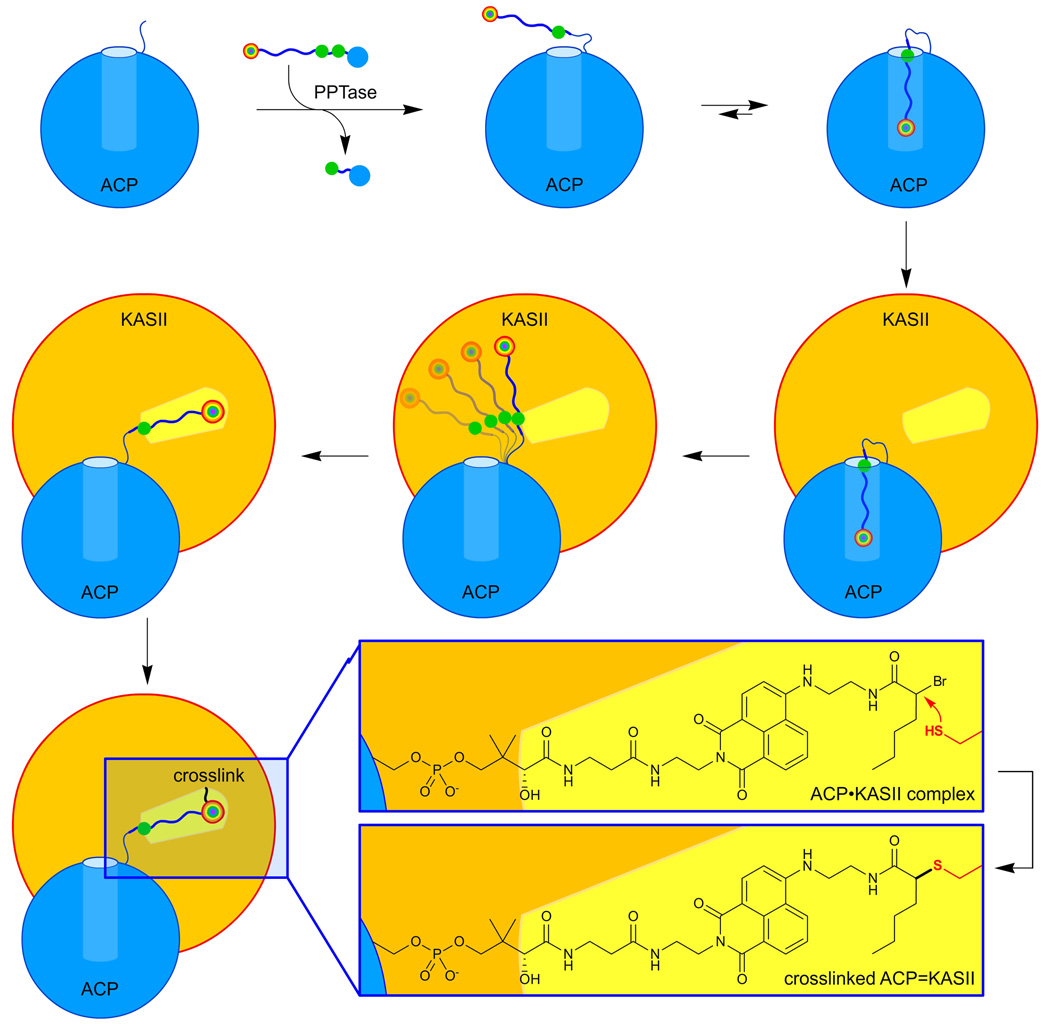

Figure 1.

Chain-flipping mechanism visualized by solvatochromism. Apo-acyl carrier protein (ACP) is loaded with a solvatochromic CoA analog using the promiscuous PPTase Sfp. The cargo is sequestered in the inner core of ACP, leading to a visible color and fluorescent signal. Addition of ketoacyl synthase II (KASII) reveals the chain-flipping mechanism in which the probe is extended into the active site of KASII. The crosslinking moiety on probe 4 forms a covalent bond with the active site cysteine of KASII.

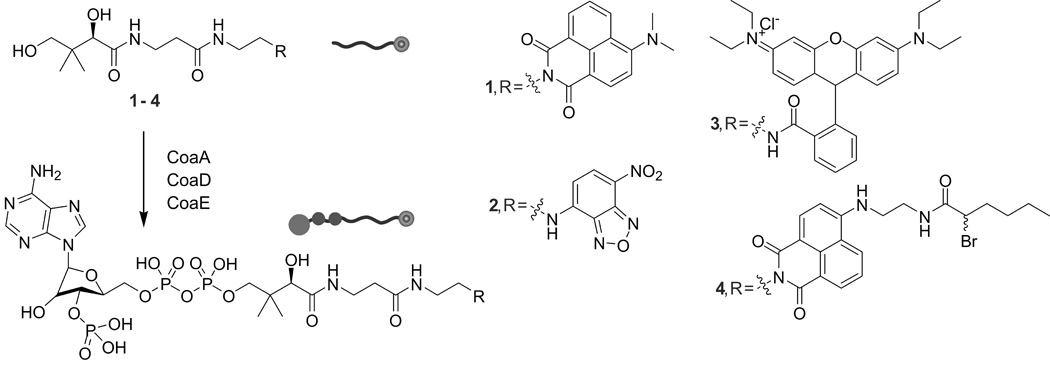

Figure 2.

Molecules used in this study. Pantetheinamide derivatives of 4-DMN (4-N,N-dimethylamino-1,8-naphthalimide) (1), Nbd (7-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole) (2) and rhodamine B (3) were synthesized from pantothenic acid via PMB-protection, 2-azidoethanamine coupling, reduction, coupling to fluorophore and deprotection. An extended solvatochromic 4-DMN-inspired mechanistic crosslinker (4) was synthesized on a protected pantetheinamide of 4-bromo-1,8-naphtalimide, reaction with ethylenediamine, coupling of 2-bromohexanoic acid and deprotection. CoaA, -D and –E transform the pantetheinamides into CoA analogs, substrates for the promiscuous PPTase Sfp, which installs these probes onto ACPs.

Next, the synthesized pantetheine probes were loaded onto a type II FAS ACP from Escherichia coli (EcACP). The probes were transformed in situ into CoA analogs and subsequently installed on ACP by the phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) Sfp.[13] The loading of ACP was monitored by conformationally sensitive UREA-PAGE[14] (Fig. S3), bands corresponding to labaled ACP excised and the proteins electroeluted for analysis by fluorescence spectroscopy and LC-MS (Fig. S4 and S5).

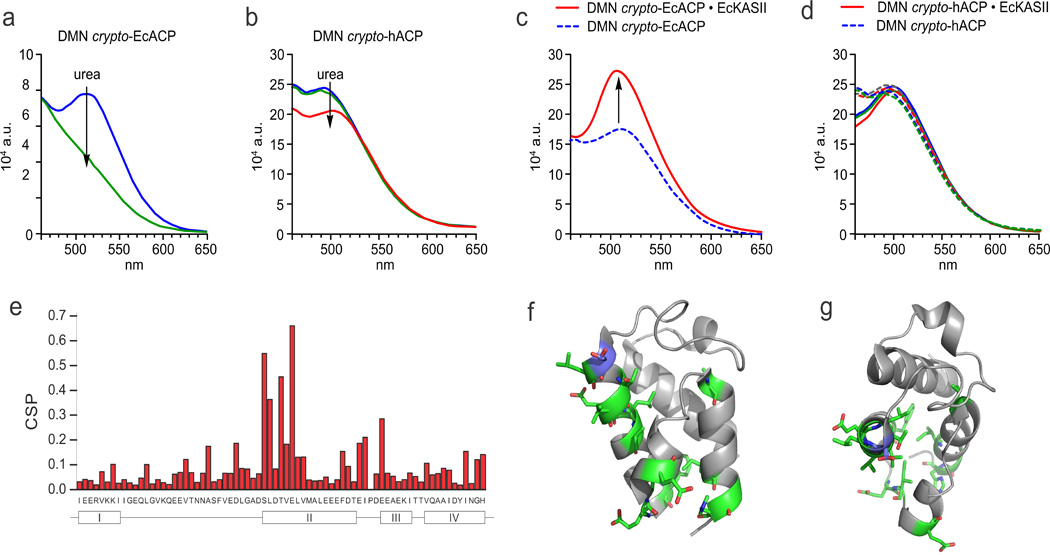

To evaluate our hypothesis of probe sequestration, we studied the behavior of labeled ACPs in solution. The results could be rapidly discerned by eye, where an aqueous solution containing EcACP bearing 4-DMN containing pantetheine analog 1 appeared bright yellow (Fig. S3 and S6). Addition of denaturant (urea or SDS) turned the solution colorless (Fig. S3 and S7) and also eliminated the fluorescent signal for 1 at 515 nm (Fig. 3a), showcasing the unfolding of the protein and exposure of the solvatochromic dye to the aqueous environment. Apo-EcACP shows no visible color or fluorescence (Fig. S6) in its native or denatured states. A high concentration of probe 1 dissolved in buffer showed no changes in fluorescence upon addition of denaturant but a significant increase and shift in fluorescence upon addition of organic solvent (acetonitrile) (Fig. S7). EcACP loaded with the Nbd-containing pantetheine analog 2 shows a marked decrease and shift in fluorescence upon denaturation. In agreement with the computational docking results, EcACP loaded with rhodamine pantetheine analog 3 shows no change in fluorescence upon denaturation, suggesting that the bulky probe is not sequestered (Fig. S8). Taken together, these solvatochromic dye-loaded ACPs replicate the phenomenon that EcACP sequesters cargo of moderate size inside the helix bundle. To validate these results, we turned to solution state NMR. Uniformly 15N-labeled apo-EcACP was loaded with analog 1, forming crypto-EcACP. Cargo sequestration by acyl-EcACP elicits significant chemical shift perturbations in 15N, 1H-HSQC spectra compared to apo- and holo-EcACP.[15] Chemical shift perturbations were observed in crypto-4-DMN-EcACP (Fig. 3e–g, S9 and table S3) comparable to those previously observed for other sequestering crypto-EcACPs,[15] validating the location of the 4-DMN probe.

Figure 3.

Solvatochromism to elucidate ACP dynamics. a) Denaturation of crypto-EcACP, modified with probe 1, measured by fluorescence spectroscopy. Upon denaturation of labeled EcACP the sequestered probe is exposed to aqueous buffer, resulting in the disappearance of the fluorescence signal and visible yellow color of the labeled protein (Fig. S3). b) The loss of the fluorescence maximum seen in (a) is not observed for crypto-hACP. c) EcKASII was titrated into EcACP and hACP (d) loaded with probe 1, monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy. Whereas the fluorescence maximum increased in the case of labeled EcACP, labeled hACP did not respond to the addition of EcKASII. e) Chemical shift perturbation plot of solution protein NMR comparing holo-EcACP to crypto-EcACP (modified with probe 1), showing typical perturbations of helix II upon cargo sequestration, providing direct evidence for the presence of probe 1 in the inner hydrophobic core of EcACP, and thus its solvatochromic behavior. f and g) Visualization of perturbed residues (in green sticks) on the protein structure (in side and top view). Serine 36, the residue which is 4’-phosphopantetheinylated, is shown in blue.

To extend this technique to type I ACPs, hACP excised from H. sapiens FAS was loaded with the solvatochromic pantetheine probes. The excised hACP readily forms a disulfide homodimer,[16] which is not a substrate for Sfp, but addition of dithiotreitol prevents this dimerization. Although computational modeling predicted no probe sequestration (Table S1 and S2), the crypto proteins showed modest fluorescence in aqueous environment (but no visible yellow color). However, in contrast with EcACP, addition of denaturant did not significantly change fluorescence (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the probes are not sequestered but associated with the surface of hACP. To explain this differential behavior, computational analysis of the electrostatic surface potential and hydrophobicity of hACP versus EcACP (Fig. S10) reveals major differences between these carrier proteins and is consistent with the localization of the dye on the protein surface.

We next turned to examine the dynamic movement of a sequestered acyl substrate from within a type II ACP into the active site of a partner enzyme, also referred to as chain-flipping.[17] This phenomenon has never been directly detected, but the protein-protein interactions governing this activity remain at the forefront of pathway engineering. Recently, two papers in Nature elegantly showed co-crystal structures of E. coli ACP with partner enzymes (LpxD[18] and FabA[1]), revealing snapshots of these protein-protein interactions.[17] The dynamic interaction between FabA and ACP was also interrogated by NMR titration experiments, however, since most likely the population of protein species involved in chain-flipping is small, this event has to date not been measured by NMR. The size of ACP-partner protein complexes pushes standard solution protein NMR to its limits, requiring novel NMR techniques like solution-state TROSY or solid-state magic-angle spinning sedimentation.[19] Indeed, when we added unlabeled E. coli ketoacyl synthase II (EcKASII, FabF) into a solution of our labeled EcACP, severe signal broadening was observed (Fig. S9). In addition, protein NMR still requires relatively large amounts of protein and is time consuming and costly. Thus, our solvatochromic approach to visualize the chain-flipping mechanism offers a facile and orthogonal way to study ACP-partner protein interactions.

We chose to interrogate ketoacyl synthase II, which extends fatty acids up to C18.[20] Previously, we have shown that EcACP loaded with chloroacrylic or α-bromo moieties can succesfully interact and crosslink with EcKASII.[21] To both EcACP and hACP loaded with 1, we titrated increasing concentrations of EcKASII and observed a significant increase in fluorescence only for EcACP (Fig. 3c). As a negative control, BSA was titrated to EcACP showing no effect (Fig. S11). Human ACP does not functionally interact with EcKASII (Fig. 3d), as analyzed by mechanistic crosslinking (not shown).[21a] These findings indicate that either EcKSII induces hydrophobicity around the pantetheine probe by compaction or EcKASII is able to extrude the cargo from the ACP for binding within its hydrophobic active site. Computational docking studies indicate that the active site of EcKASII can accommodate probe 1 (Fig. S12), suggesting that chain-flipping activity is responsible for increase in fluorescence.[22]

As mentioned, we recently introduced mechanistic crosslinking as a tool to capture protein-protein interactions between carrier proteins and their partners.[21a] We hypothesized that crosslinking could be used to conclusively deduce the source of the increase in fluorescence signal upon addition of EcKASII to EcACP loaded with probe 1. Therefore solvatachromic-crosslinking probe 4 was prepared, and its loading onto EcACP resulted in a yellow color change and fluorescence response. Addition of EcKASII resulted in a crosslinked complex with increased fluorescence, as visualized by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S13), with a molecular weight of 54 kDa. Isolation of solvatochromic crosslinked EcACP-EcKASII, shows a strong fluorescence signal (Fig. S14A), although EcACP labeled with 4 itself gave a low fluorescence signal (Fig. S14B). Titration of EcKASII to EcACP labeled with 4 shows appearance of a strong fluorescence signal, albeit only after incubation overnight (Fig. S14B). Incubation of EcKASII with 4 alone did not result in fluorescence (Fig. S14C), suggesting that protein-protein interactions between ACP and ketoacyl synthase are required for binding of 4 within EcKASII. As expected, hACP loaded with 4 did not crosslink with EcKASII (data not shown). These results indicate that the solvatochromic fluorescent response with 4 is indeed a result of its transition from sequestration within EcACP to the active pocket of EcKASII. The increased fluorescence response therefore provides a direct response for chain-flipping activity.

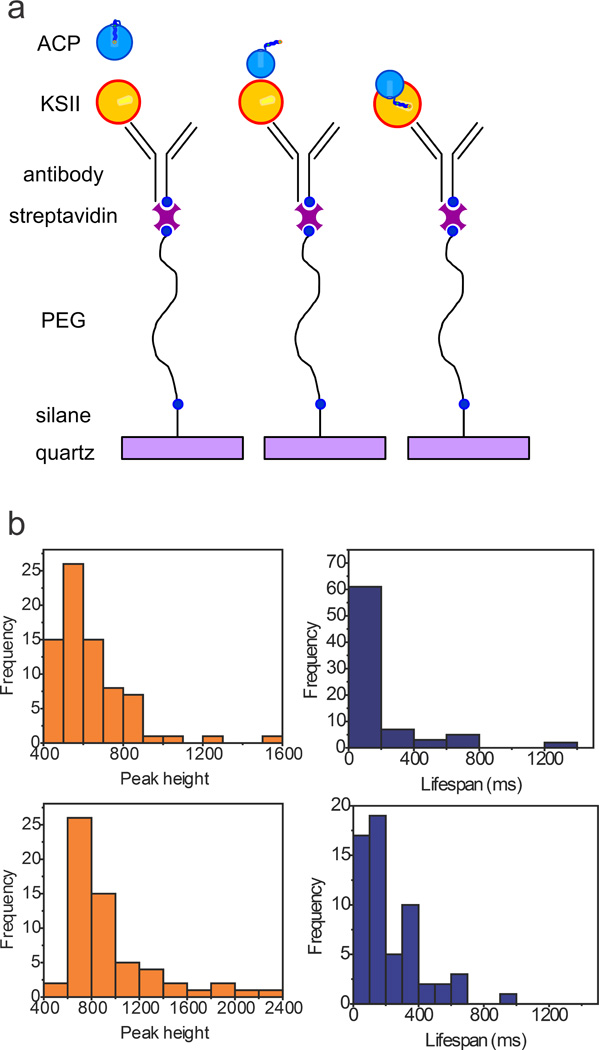

Single molecule fluorescence microscopy is emerging as a valuable technique to study biological processes such as protein trafficking in living organisms and interrogation of protein-protein interactions.[23] We reasoned that solvatochromic response from chain-flipping activity could be applied to single molecule fluorescence microscopy, whereby single binding events between EcACP and EcKASII could be quantified. Here, we attached EcKASII to a quartz surface and flowed DMN-labeled EcACP over the surface (Fig. 4a) while collecting a video of fluorescent events (Fig. 4b). Many bright events were observed, in contrast to flowing pantetheine probe 1 over the same surface. Interestingly, > 85% of the brightest spots picked by the software were distinct peaks with a clear signal intensity over background and a defined lifespan (Fig. 4b), whereas flowing the probe (1) alone resulted in some bright spots, from which < 20% are peaks (possibly originating from aggregation). Flowing labeled EcACP over an unmodified PEG surface resulted in ~60% peaks, but with very different intensities and ‘ON’ time (lifespan) distribution (Fig. 4b). In the case of labeled EcACP-EcKASII, the lifespan times were short, and peak intensity distributions were narrow, indicating that the interactions with the partner protein (KASII) changed the environment of the probe attached to EcACP significantly. Conversely, in the case of labeled EcACP flowing over an unmodified PEG surface, peak intensities were substantially increased, and the lifespans showed more variation (Fig. 4b). We also modified EcKASII with Cy5 and performed a co-localization experiment, using two different lasers, exciting either the Cy5 dye-labeled EcKASII or the DMN-labeled EcACP. Whereas this experiment is normally used for tight binding events, we are interrogating transient interactions between ACP and KS, complicating the analysis. However, a nontrivial population (~8%), compared to the statistical probability (~3%) showed bright fluorescent events in exactly the same location, in both channels, suggesting that we are indeed interrogating ACP-partner protein interactions (Fig. S15). The significant difference in fluorescence response at the single molecule level functionally demonstrates chain-flipping activity triggered by protein-protein interactions between EcACP and EcKASII. We envision that this single molecule approach can be used to rapidly screen ACP-partner protein interactions at very low concentrations, in the future.

Figure 4. Single molecule fluorescence behavior of DMN-labeled EcACP.

a) On a quartz surface, a layered design was patterned to provide sufficient spacing between proteins and to prevent surface effects. A sandwich approach for attachment of EcKASII used the sequential layering of aminosilane, biotinylated-PEG, streptavidin, and biotinylated anti-(His)6-antibody, and (His)6-tagged EcKASII. DMN-labeled EcACP was flowed over the decorated surface with video collection of fluorescent events. b) Time-lapsed images were collected, visualizing the bleaching of single molecules. Bright pixels were detected, and human analyses were performed to unselect aberrant data points. After selection, fluorescence intensity was plotted over time and observed peaks analyzed. Peak height is an arbitrary value of signal intensity and lifespan represents the width of the observed fluorescent peaks. top: DMN-EcACP flowed over EcKASII and bottom: DMN-EcACP flowed over unmodified PEG. Pantetheine probe 1 flowed over EcKASII does not show any significant fluorescent events.

In this work we introduce a biophysical tool to probe the dynamics of ACP with solvatochromic dyes. The attachment of these pantetheine probes to two different ACPs enabled us to evaluate substrate sequestration and visualize chain-flipping upon interaction with a partner protein. NMR spectroscopy has previously been used to demonstrate that type I ACPs do not demonstrate sequestration; the present methods efficiently verified those findings.[6] It should be noted however that the probes used here are not fatty acids, and that type I ACPs in the context of their synthase might behave differently. Importantly however, we showed a simple and quick technique to visualize protein-protein interactions between ACP and partner enzymes. By matching EcACP with EcKASII, we demonstrated both selectivity and a sensitive readout for protein-protein interactions. The development of a solvatochromic-crosslinking probe with a novel dual-purpose functionalization, allowed us to validate chan-flipping activity as a source of increased solvatochromic response. Finally, single molecule fluorescence reports the outcome of individual chain-flipping events, with lifespan comparisons that indicate selectivity between EcACP and EcKASII as stabilized by protein-protein interactions.

Solvatochromic pantetheine probes also enable sequestration studies of other carrier proteins, including those from polyketide and non-ribosomal peptide biosynthetic pathways. Further, these tools pave the way for dynamic studies of protein-protein interactions between the various partners of carrier proteins in type II synthases. Facile access to these probes, which do not require complex synthetic techniques, allows for broad use such as the selection of new catalytic partners for synthetic biology. Combination of this technique with time-correlated single photon counting fluorescence spectroscopy[24] or vibrational spectroscopy[25] will allow accurate modeling of the chain-flipping phenomenon. Other potential applications include a turn-on dye for ACP-fusion proteins to quickly visualize their cellular localization.

Experimental Section

Experimental Details can be found in the SI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

JB was supported by a Rubicon postdoctoral fellowship. MDB and JB were funded by California Energy Commission CILMSF 500-10-039; DOE DE-EE0003373; NIH R01GM094924 and R01GM095970. We would like to thank J. J. La Clair for fruitful discussions and support, X. Huang and D. J. Lee for training and support with solution protein NMR spectroscopy and T. L. Foley (NIH) for the plasmid encoding H. sapiens ACP.

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.Nguyen C, Haushalter RW, Lee DJ, Markwick PRL, Bruegger J, Caldara-Festin G, Finzel K, Jackson DR, Ishikawa F, O/'Dowd B, McCammon JA, Opella SJ, Tsai S-C, Burkart MD. Nature. 2014;505:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers DM, Gong H. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;85:649–662. doi: 10.1139/o07-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby J, Crump MP. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:1111–1137. doi: 10.1039/c2np20062g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zornetzer GA, Fox BG, Markley JL. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5217–5227. doi: 10.1021/bi052062d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan DI, Tieleman DP, Vogel HJ. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2860–2868. doi: 10.1021/bi901713r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Płoskoń E, Arthur CJ, Evans SE, Williams C, Crosby J, Simpson TJ, Crump MP. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:518–528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wattana-amorn P, Williams C, Ploskoń E, Cox RJ, Simpson TJ, Crosby J, Crump MP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2186–2193. doi: 10.1021/bi902176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Loving G, Imperiali B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13630–13638. doi: 10.1021/ja804754y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Loving GS, Sainlos M, Imperiali B. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Reichardt C. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2319–2358. [Google Scholar]; b) La Clair JJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:325–329. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<325::AID-ANIE325>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worthington AS, Burkart MD. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:44–46. doi: 10.1039/b512735a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexiou MS, Tychopoulos V, Ghorbanian S, Tyman JHP, Brown RG, Brittain PI. J. Chem. Soc. Perk. Trans. 2. 1990:837–842. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fery-Forgues S, Fayet JP, Lopez A. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 1993;70:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinckley DA, Seybold PG, Borris DP. Spectrochim. Acta, Pt. A: Mol. Spectrosc. 1986;42:747–754. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beld J, Sonnenschein EC, Vickery CR, Noel JP, Burkart MD. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31:61–108. doi: 10.1039/c3np70054b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Post-Beittenmiller D, Jaworski J, Ohlrogge J. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1858–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa F, Haushalter RW, Lee DJ, Finzel K, Burkart MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8846–8849. doi: 10.1021/ja4042059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi AK, Zhang L, Rangan VS, Smith S. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33142–33149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cronan JE. Biochem. J. 2014;460:157–163. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masoudi A, Raetz CRH, Zhou P, Pemble CW., Iv Nature. 2014;505:422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature12679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mainz A, Religa TL, Sprangers R, Linser R, Kay LE, Reif B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8746–8751. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Agnolo G, Rosenfeld I, Vagelos P. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:5289–5294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Worthington AS, Rivera H, Torpey JW, Alexander MD, Burkart MD. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006;1:687–691. doi: 10.1021/cb6003965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Beld J, Blatti JL, Behnke C, Mendez M, Burkart MD. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10811-013-0203-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leibundgut M, Jenni S, Frick C, Ban N. Science. 2007;316:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1138249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pappas D, Burrows SM, Reif RD. Trends Anal. Chem. 2007;26:884–894. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLean AM, Socher E, Varnavski O, Clark TB, Imperiali B, Goodson T., III J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:15935–15942. doi: 10.1021/jp407321g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MNR, Londergan CH, Charkoudian LK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11240–11243. doi: 10.1021/ja505442h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.