Abstract

Background

Limb-sparing surgery for osteosarcoma requires taking wide bony resection margins while maximizing preservation of native bone and joint. However, the optimal bony margin and factors associated with recurrence and survival outcomes in these patients are not well established.

Procedure

We conducted a retrospective review of outcomes in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma from 1986–2012, where bony resection margins for limb-sparing surgeries were decreased serially from 5 to 1.5 cm. The association between bony margins and other surgicopathological factors with survival and recurrence outcomes was determined.

Results

In 181 limb-sparing surgeries in 173 patients, planned and actual bony resection margins were not significantly associated with local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), event-free survival (EFS), and overall survival (OS) – at median 5.8 years follow-up, decreasing planned bony resection margins from 5 to 1.5 cm did not significantly decrease survival outcomes. Multivariable analysis showed that the presence of distant metastases at diagnosis was associated with decreased LRFS, EFS, and OS (P=0.002, 0.005 and <0.0001, respectively). Post-chemotherapy tumor necrosis ≤90% was associated with decreased EFS and OS (P=0.001 and 0.022, respectively). Earlier years of treatment and pathologic fractures were associated with decreased OS only (P=0.018, and 0.008, respectively); previous cancer history and male gender were associated with decreased EFS only (P=0.043 and 0.023, respectively).

Conclusion

We did not observe significant increase in adverse survival outcomes with reduction of longitudinal bony resection margins to 1.5 cm. Established prognostic factors, particularly histologic response to chemotherapy and metastases at diagnosis, remain relevant in limb-sparing patients.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, limb salvage, osteotomy, neoplasm recurrence, local, resection margin

INTRODUCTION

In limb-sparing surgery for extremity osteosarcoma, the priority of oncologic local control needs to be balanced against the biomechanical advantage of retaining more healthy bone. The primary tumor must be resected with sufficiently wide margins while retaining as much native bone and joint as possible. However, no benchmark exists to define a “sufficiently wide” margin that does not compromise local control. In children, limiting the extent of resection optimizes joint function and growth by sparing the epiphysis and preserving the natural joint [1]. Maximizing remaining bone length also aids bony reconstruction and improves implant or graft longevity.

The association of limb-sparing surgery with inadequate bony margins and with local recurrence risk remains controversial. Both multi- and single-center studies involving adults and children have shown that limb-sparing surgeries are associated with a higher incidence of inadequate bony resection margins – defined by Enneking as marginal, intralesional or contaminated margins [2–6]. Although some studies conclude that limb-sparing surgery increases the risk of local recurrence because of the need for close resection margins, others suggest that these differences are related to surgical expertise. While the consensus is to obtain wide margins for local control, recent studies suggest that marginal resections are adequate with selected adjuvant therapies [7–9]. Establishing a benchmark for a sufficient bony resection margin is important to help guide choices for surgical options for local control.

Limb-sparing resections can be planned based on preoperative imaging. The intraosseous length of abnormal bone marrow signal in extremity osteosarcoma does not change significantly with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [10], and tumor measurements on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) correlate accurately with actual tumor dimensions on histology [11–13]. Thus, pre-chemotherapy MRI can be used reliably to plan surgical resections and determine the length of endoprostheses required for reconstruction.

In this retrospective study, we evaluated the association of bony resection margins and other surgicopathological factors with oncologic outcomes in children and adolescents undergoing limb-sparing surgery for resection of extremity osteosarcoma. By using serial decrements in bony resection margins over consecutive prospective clinical trials, we determined the shortest bony margin that did not compromise survival outcomes.

METHODS

Patients

Patients with high-grade extremity osteosarcoma who underwent limb-sparing surgeries between July 1986 and June 2012 were identified through hospital databases and records of treatment protocols. Patients with axial tumors, low- or intermediate-grade tumors, and those who underwent amputations for local control were excluded. Patient records, radiographic images, and pathological reports and section maps were individually reviewed. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Treatment approach

All patients were treated with pre- and post-operative chemotherapy (Table I). Although all patients were eligible for limb-sparing surgery, individual suitability was determined based on the likelihood of a successful wide resection. The aim of surgical control of the primary tumor was always to obtain wide or radical margins according to Enneking’s classification [14], incorporating skip metastases when present. Specific contraindications to limb salvage included any situation which would preclude the possibility of a complete resection, and patient preference.

TABLE I.

Summary of treatment protocols.

| Protocol, time period | Chemotherapy | Timing of surgery | Preoperative tumor imaging | Planned surgical margin (cm) | Surgeries performed during time period [n (%of entire study cohort)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS-8615 (1986–1991) | IFO, HDMTX, DOX | Week 13 | X-ray, CT, MR, 99TcDMP | 5 | 11 (6.1) |

| OS-9116 (1991–1997) | IFO/CBP | Week 10 | X-ray, CT, MR, 99TcDMP | 5 | 50 (27.6) |

| OS-9917 (1999–2006) | IFO, CBP, DOX | Week 12 | X-ray, CT, MR, 99TcDMP | 3 | 81 (44.8) |

| OS-08 (2008–2012) | CDDP/DOX/HDMTX, BEV, ± IFO/ETOP | Week 10 | X-ray, MR, 99TcDMP | 1.5 | 39 (21.5) |

DOX, doxorubicin; CBP, carboplatin; CYC, cyclophosphamide; HDMTX, high-dose methotrexate; IFO, ifosfamide; ETOP, etoposide; CDDP, cisplatin; BEV, bevacizumab; CT, computed tomography scan; MR, magnetic resonance imaging; 99TcDMP, technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate bone scan.

The length of the longitudinal bony resection and distance of the bony margin were planned using the imaging study performed at diagnosis, and reconfirmed on repeat imaging just before surgery. This was performed consistently in all cases by a single investigator. During surgery, osteotomy sites were determined by correlating preoperatively planned distances from bony landmarks with measurements taken on intraoperative fluoroscopy. Following the osteotomies, biopsies of adjacent un-diseased bone marrow were evaluated with frozen section histology before proceeding with bony reconstruction. Actual bony margins were confirmed on final permanent histological sections, and were determined as the closest longitudinal distance between the tumor and cut surface of the bone. Improved resolution of preoperative imaging allowed reduction of the distance of the planned bony resection margin from 5 cm to 1.5 cm over the years (Table I). The planned and actual bony margins on final histology were recorded and correlated with survival and local recurrence outcomes. An inclusive stance was taken, defining all loco-regional recurrences occurring in close proximity to the original surgical field as local recurrences, regardless of whether they were in or in the vicinity of the same bone as the primary tumor.

Statistical analysis

Cox regression models were used to evaluate associations between outcomes of interest—LRFS, OS, and EFS—and distance of planned and actual bony resection margins, and other known prognostic factors: tumor site, extent of necrosis, ratio of longitudinal length of tumor to bone, pathologic fracture, skip metastases, positive bony or soft tissue resection margins, and presence of distant metastases at diagnosis. Patient age, gender, race, history of previous cancer, treatment protocol, and year of treatment were also evaluated. Analyses for outcomes were conducted independently. Single imputation (replacement of missing data points with the median value) was performed for 5 cases with missing Rosen grades and 1 case with missing longitudinal tumor and bone lengths. Backward selection was used to identify the variables for the final multiple Cox-regression models, which reported results of all factors that remained significant at the 5% level.

LRFS, EFS, and OS distributions were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. LRFS was defined as the time from diagnosis by biopsy to local failure, and EFS was defined as the time from diagnosis by biopsy to local or distant failure or death due to any cause. All local and distant failures were confirmed by histology. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis by biopsy to death due to any cause. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Patient and tumor characteristics

Over 26 years, 248 resections for extremity osteosarcoma were performed – 67 amputations in 65 patients and 181 limb-sparing resections in 173 patients. Median age of patients was 13.6 years (range, 3.2–23.6 years). Eleven patients had prior malignancies, including retinoblastoma (n=3) and previous osteosarcoma in a different bone (n=8). The latter were regarded as a second cancer rather than metachronous distant metastases due to long time intervals between prior and present cancers (mean 5.3 +/− 3.1 years). One patient had limb-sparing surgery for the recurrent tumor. Median longitudinal tumor length measured on preoperative imaging was 10.6 cm (range, 1–30.4 cm), a median of 26.5% of the length of the affected bone (range, 2.5%–77.7%). On final histology, median tumor length was very similar (9.0 cm; range, 1.5–37.0 cm), confirming the accuracy of preoperative MRI in evaluating actual tumor dimensions.

Actual and planned bony resection margins

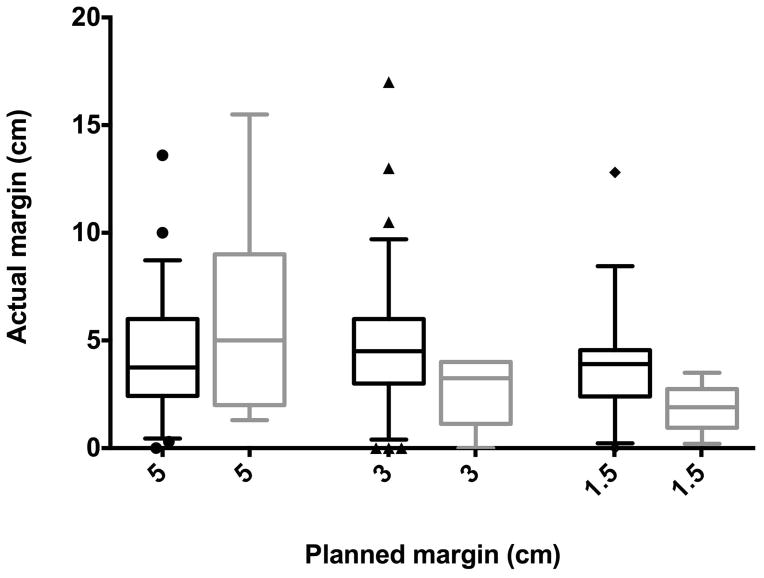

The median actual bony resection margin was 4.0 cm (range, 0.0–17.0 cm) for the entire cohort. Nine patients had positive margins. Actual margins were longer than planned in 111 (61.3%) surgeries; 52 (of 111) were longer by more than 2 cm. Actual margins were shorter than planned in 62 (34.3%) surgeries; 25 (of 62) were shorter by more than 2 cm. Actual margins were shorter for planned margins of 5 cm (median 3.8 cm), and longer for planned margins of 3 and 1.5 cm (median 4.5 and 3.5 cm, respectively). There was no association between actual and planned resection (correlation coefficient ρ=0.09, P=0.228). In patients that developed local recurrence, planned and actual bony margins were similar, with median actual bony margins of 5.0, 3.3, and 1.9 cm for patients that had planned margins of 5, 3, and 1.5 cm, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Box plots showing no significant difference between planned and actual bony resection margins for patients without local recurrence (black boxes) and patients with local recurrence only (grey boxes).

Outcomes

At a median follow-up of 5.8 years (range, 0.3–25.9 years), there were 18 (9.9%) local recurrences, 41 (22.6% ) distant recurrences, and 6 (3.3%) concurrent local and distant recurrences. Fifty-one (29.5%) patients died of their disease, and 3 (1.7%) died of other causes. OS estimates at 5, 10 and 15 years were 73.7% (±3.5%), 68.6% (±3.9%), and 58.1% (±5.6%), respectively. The median (range) times to local recurrence, death, and disease event (local or distant failure, or death) were 1.38 (0.62–10.38), 2.19 (0.35–16.42), and 1.69 (0.02–16.42) years, respectively. Local recurrence rates were 11.5% for procedures with planned bony margins of 5 cm (7 of 61), 7.4% for those with planned margins of 3 cm (6 of 81), and 12.8% for those with planned margins of 1.5 cm (5 of 39).

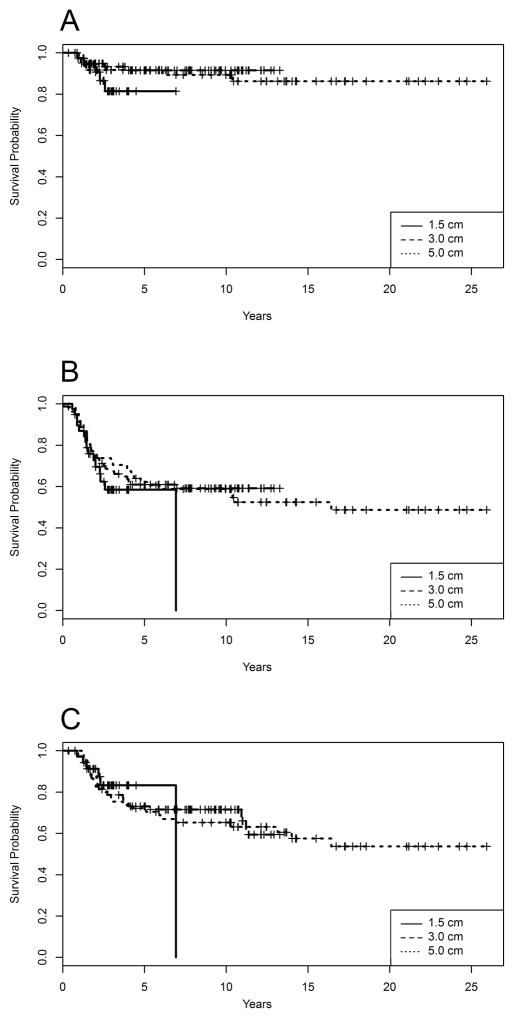

Forty-one percent, 30.3% and 16.7% of patients died in the subgroups with planned margins of 5.0, 3.0, and 1.5cm, respectively. LRFS, EFS and OS did not differ significantly among these 3 subgroups (log-rank test P=0.349, 0.392 and 0.935 respectively) (Fig. 2). The survival curves for patients with 1.5 cm margins drop sharply due to a death occurring after the last censoring.

Fig 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of local recurrence–free survival (A), event-free survival (B), and overall survival (C), according to planned bony resection margins.

Predictors of outcome

Univariate analysis showed that decreased LRFS, EFS, and OS were significantly associated with presence of distant metastases at diagnosis and history of a previous cancer. EFS and OS were associated with post-chemotherapy tumor necrosis ≤90%, (Table II). Planned and actual bony resection margins were not significantly associated with LRFS, EFS, and OS; that is, serially decreasing planned bony resection margins from 5 to 1.5 cm did not adversely affect survival outcomes.

TABLE II.

Univariate analysis of factors predictive of outcome.

| Factor | Surgeries (N) | 5- year LRFS probability (SE) | P | 5-year EFS probability (SE) | P | Patients (N) | 5-year OS probabilit y (SE) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient factors | ||||||||

| Age* | 181 | 0.901 (0.027) | 0. 7386 | 0.602 (0.063) | 0.696 | 173 | 0.739 (0.047) | 0.7394 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 94 | 0. 888 (0.039) | 0.5847 | 0.512 (0.103) | 0.0012 | 87 | 0. 680 (0.074) | 0. 0598 |

| Female | 87 | 0.912 (0.034) | 0.693 (0.071) | 86 | 0. 795 (0.053) | |||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 125 | 0.899 (0.031) | 0.9964 | 0.613 (0.072) | 0.8438 | 120 | 0. 741 (0.054) | 0.8708 |

| African American | 45 | 0.903 (0.052) | 0.566 (0.130) | 42 | 0. 716 (0.095) | |||

| Other | 11 | 0.896 (0.110) | 0.589 (0.266) | 11 | 0. 794 (0.164) | |||

| History of previous cancer | ||||||||

| Absent | 169 | 0.913 (0.026) | 0.0299 | 0.630 (0.062) | 0.0004 | 162 | 0.752 (0.046) | 0.0162 |

| Present | 12 | 0.692 (0.216) | 0.212 (0.502) | 11 | 0.367 (0.504) | |||

| Disease factors | ||||||||

| Tumor site | ||||||||

| Lower extremity | 0.911 (0.027) | 0.1962 | 0.629 (0.064) | 0.0415 | 0.760 (0.047) | 0.0563 | ||

| Femur | 108 | 105 | ||||||

| Tibia | 39 | 37 | ||||||

| Fibula | 10 | 10 | ||||||

| Upper extremity | 0.824 (0.099) | 0.433 (0.219) | 0.584 (0.74) | |||||

| Humerus | 23 | 20 | ||||||

| Ulna | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Distant metastases at diagnosis | ||||||||

| Absent | 135 | 0.946 (0.021) | 0.0005 | 0.684 (0.060) | <0.0001 | 132 | 0.823 (0.041) | <0.0001 |

| Present | 46 | 0.741 (0.099) | 0.363 (0.192) | 41 | 0.460 (0.169) | |||

| Pathologic fracture | ||||||||

| Absent | 175 | 0.898 (0.027) | 0.789 | 0.606 (0.064) | 0.3906 | 167 | 0.747 (0.047) | 0.0814 |

| Present | 6 | 0.999 (0.013) | 0.436 (0.480) | 6 | 0.438 (0.480) | |||

| Skip metastases | ||||||||

| Absent | 166 | 0.898 (0.028) | 0.819 | 0.606 (0.065) | 0.5736 | 158 | 0.756 (0.047) | 0.0664 |

| Present | 15 | 0.919 (0.085) | 0.535 (0.238) | 15 | 0.553 (0.226) | |||

| Ratio of axial length of tumor to bone* | 181 | 0.928(0.033) | 0.7891 | 0.603 (0.064) | 0.2895 | 173 | 0.742 (0.048) | 0.401 |

| Treatment factors | ||||||||

| Planned bony resection margin (cm) | ||||||||

| 1.5 | 39 | 0.832 (0.085) | 0.3657 | 0.498 (0.188) | 0.4379 | 36 | 0.763 (0.112) | 0.9354 |

| 3 | 81 | 0.926 (0.032) | 0.626 (0.085) | 76 | 0.740 (0.066) | |||

| 5 | 61 | 0.900 (0.043) | 0.613 (0.097) | 61 | 0.726 (0.074) | |||

| Actual bony resection margin (cm)* | 181 | 0.916(0.026) | 0.1429 | 0.601 (0.064) | 0.8629 | 173 | 0.740 (0.047) | 0.8622 |

| Bony resection margin | ||||||||

| Negative | 172 | 0.901 (0.027) | 0.804 | 0.613 (0.063) | 0.1345 | 164 | 0.749 (0.047) | 0.1353 |

| Positive | 9 | 0.874 (0.135) | 0.396 (0.381) | 9 | 0.558 (0.265) | |||

| Soft tissue resection margin | ||||||||

| Negative | 176 | 0.897 (0.028) | 0.7705 | 0.604 (0.064) | 0.6161 | 169 | 0.743 (0.048) | 0.4477 |

| Positive | 5 | 0.999 (0.012) | 0.508 (0.392) | 4 | 0.597 (0.365) | |||

| Tumor necrosis (Rosen grade) | ||||||||

| ≤90% | 0.875 (0.042) | 0.2761 | 0.484 (0.108) | 0.0007 | 0.673 (0.075) | 0.0337 | ||

| 1 | 48 | 45 | ||||||

| 2 | 46 | 43 | ||||||

| >90% | 0.924 (0.031) | 0.727 (0.065) | 0.804 (0.051) | |||||

| 3 | 70 | 69 | ||||||

| 4 | 17 | 17 | ||||||

| Treatment plan | ||||||||

| On protocol | 118 | 0.918 (0.029) | 0.2805 | 0.614 (0.075) | 0.5939 | 114 | 0.743 (0.056) | 0.8422 |

| Non-protocol treatment plan | 63 | 0.866 (0.052) | 0.575 (0.109) | 59 | 0.792(0.078) | |||

| Year of treatment* | 181 | 0.900(0.027) | 0.7460 | 0.593 (0.067) | 0.0872 | 173 | 0.743 (0.049) | 0.4619 |

Analyzed as continuous variables.

P-values in bold are significant at α=.10.

LRFS, local recurrence-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; OS, overall survival; SE, standard error.

Multiple Cox regression showed that presence of distant metastases at diagnosis was significantly associated with LRFS, EFS and OS. Post-chemotherapy tumor necrosis ≤90%, earlier years of treatment and presence of pathologic fracture were associated with decreased OS; history of previous cancer, tumor necrosis ≤90%, and male gender were associated with decreased EFS (Table III).

TABLE III.

Multivariate analysis of factors predictive of outcome.

| 5-year LRFS probability | 5-year EFS probability | 5-year OS probability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI.) | P | |

| Tumor necrosis (>90%: ≤90%) | 0.606 | (0.231–1.588) | 0.3082 | 0.450 | (0.277–0.729) | 0.0012 | 0.523 | (0.301–0.909) | 0.0216 |

| Distant metastases at diagnosis (present: absent) | 4.763 | (1.740–13.044) | 0.0024 | 2.061 | (1.251–3.395) | 0.0045 | 4.741 | (2.597–8.654) | <0.0001 |

| History of previous cancer (present: absent) | 1.906 | (0.511–7.112) | 0.3371 | 2.080 | (1.022–4.233) | 0.0434 | 2.965 | (0.946–9.297) | 0.0624 |

| Pathologic fracture (present: absent) | * | * | 5.262 | (1.554–17.817 | 0.0076 | ||||

| Year of treatment | * | * | 0.545 | (0.330–0.902) | 0.0183 | ||||

| Gender(female: male) | 0.923 | (0.358–2.377) | 0.8683 | 0.576 | (0.358–0.925) | 0.0226 | * | ||

Variable did not enter into multivariate model.

P-values in bold are significant at <0.05.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; LRFS, local recurrence-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; OS, overall survival.

DISCUSSION

In our series of children and adolescents undergoing limb-sparing surgery for extremity osteosarcoma, we did not observe significant increase in adverse survival outcomes with reduction of bony resection margins down to 1.5 cm. Consistent with previous reports, we found that the degree of tumor necrosis and the presence of distant metastases at diagnosis were independently associated with decreased OS and EFS.

Bony resection margins planned on preoperative MRI correlated well with the actual osteotomies executed with intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging guidance. Actual and planned bony margins varied by a median of 1.5–2.0 cm. Actual margins tended to be longer in more recent cases, mostly because of having to accommodate expandable endoprostheses with adequate expansion capacity. It has been shown that MRI can accurately estimate true tumor dimensions in osteosarcoma, in particular with T1-weighted imaging, and with minimal interpersonal differences in interpretation [10, 18]. In our previous study, pre- and post-chemotherapy T1-weighted images overestimated tumor length by median 1 cm in 16% of cases and underestimated it in 14% of cases. Although the latter is of greater concern when planning tumor resections, median underestimation was only 2 cm (range, 1–5 cm) on pre-chemotherapy imaging and 1 cm (range, 1–2 cm) after chemotherapy. Thus, a planned bony margin of at least 1.5 cm should compensate for any under-representation of true tumor dimensions on MRI.

Shorter planned bony resection margins down to 1.5 cm were not significantly associated with adverse survival outcomes. Arbitrary resection margins of 2–3 cm have been recommended in various papers and texts for central [19–22] and peripheral osteosarcoma [23–25]. Our findings agree with the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group’s analysis of 123 osteosarcoma patients where bony resection margins of 0.1–1.0 cm versus 1.1–2.0 cm did not significantly impact 2- and 5-year local recurrence rates [26]. Among their patients who had limb-sparing surgery, median bony resection margin was 4.5 cm, similar to our study (median bony margin 4.0 cm). In a small pilot series utilizing multiplanar osteotomies with a minimum 1 cm bony margin, there were no local recurrences in 4 patients with lower-extremity osteosarcoma at 2-year follow-up [27].

The only 2 prognostic variables found to be independently associated with EFS and OS were related to the biological behavior of the tumor–in its propensity for distant spread and its sensitivity or resistance to chemotherapy. In contrast, other analyses have identified positive resection margins and poor response to preoperative chemotherapy as independent risk factors for local recurrence [28–32]. These studies included both patients undergoing limb-sparing surgery and amputation, and may not be directly comparable. Tumors amenable to limb-sparing surgery may differ from those considered for amputation. The former may have less neurovascular invasion, and may be more proximal, smaller [33] and less aggressive. In the current era of limb-sparing surgery, the main challenge in improving outcomes for extremity osteosarcoma may lie more with the treatment of systemic disease than local control.

The key limitation was the long study period during which time the chemotherapy protocols advanced significantly. The more effective chemotherapy in more recent protocols may have confounded our analysis by masking potential adverse effects of decreasing the bony resection margin. Also the significant association of year of treatment with overall survival may have been confounded by the decreased follow-up duration in more recent cases. Soft tissue margin distance was not considered in our study, as this variable was limited by the close proximity of these tumors to neurovascular structures, which had to be preserved. As resection margin is determined by the surgeon’s judgment, there may exist a potential intervention bias where margins may be adjusted according to the surgeon’s impression of the patient’s therapeutic response or prognosis. Also, although local recurrence rates in the group with 1.5 cm margins was slightly higher, the LRFS did not differ significantly. Thus, the study cannot make definitive conclusions about the association between decreased resection margins and local recurrence rates. Also, within the short period of follow-up, particularly for the cohort with 1.5 cm margins, true differences in LRFS, EFS and OS may not have become apparent.

For extremity osteosarcomas in children and adolescents, our data suggest that limb-sparing resections may be performed with longitudinal bony margins of down to 1.5 cm without significantly increasing the risk of adverse survival outcomes. T1-weighted MRI can accurately determine true tumor dimensions and can be reliably used to plan surgical resections. In children who have undergone limb-sparing surgery for osteosarcoma, poor response to preoperative chemotherapy and metastatic disease at diagnosis independently predict event-free and overall survival.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Cancer Center Support (CORE) grants CA-21765 and CA-23099 from National Cancer Institute and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Mankin HJ, Gebhardt MC, Jennings LC, et al. Long-term results of allograft replacement in the management of bone tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;324:86–97. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacci G, Longhi A, Versari M, et al. Prognostic factors for osteosarcoma of the extremity treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: 15-year experience in 789 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2006;106:1154–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimer RJ, Taminiau AM, Cannon SR Surgical Subcommitte of the European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. Surgical outcomes in osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:395–400. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b3.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosjö O. Surgical procedure and local recurrence in 223 patients treated 1982–1997 according to two osteosarcoma chemotherapy protocols. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group experience. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1999;285:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sluga M, Windhager R, Lang S, et al. Local and systemic control after ablative and limb sparing surgery in patients with osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;358:120–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacci G, Ferrari S, Lari S, et al. Osteosarcoma of the limb. Amputation or limb salvage in patients treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:88–92. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b1.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong CB, Song WS, Cho WH, et al. Local recurrence has only a small effect on survival in high-risk extremity osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1482–1490. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Moretti VM, Ashana AO, Lackman RD. Impact of close surgical margin on local recurrence and survival in osteosarcoma. Int Orthop. 2012;36:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu XC, Xu M, Song RX, Xu SF. Marginal resection for osteosarcoma with effective preoperative chemotherapy. Orthop Surg. 2009;1:196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-7861.2009.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onikul E, Fletcher BD, Parham DM, Chen G. Accuracy of MR imaging for estimating intraosseous extent of osteosarcoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1211–1215. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.5.8911182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespy T, 3rd, Manfrini M, Ruggieri P, et al. Staging of intraosseous extent of osteosarcoma: correlation of preoperative CT and MR imaging with pathologic macroslides. Radiology. 1988;167:765–767. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.3.3163153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloem JL, Taminiau AH, Eulderink F, et al. Radiologic staging of primary bone sarcoma: MR imaging, scintigraphy, angiography, and CT correlated with pathologic examination. Radiology. 1988;169:805–810. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.3.3055041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffer FA, Nikanorov AY, Reddick WE, et al. Accuracy of MR imaging for detecting epiphyseal extension of osteosarcoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:289–298. doi: 10.1007/s002470050743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;153:106–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daw NC, Billups CA, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2006;106:403–412. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer WH, Pratt CB, Poquette CA, et al. Carboplatin/ifosfamide window therapy for osteosarcoma: results of the St Jude Children's Research Hospital OS-91 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:171–182. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daw NC, Neel MD, Rao BN, et al. Frontline treatment of localized osteosarcoma without methotrexate: results of the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital OS99 trial. Cancer. 2011;117:2770–2778. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones KB, Ferguson PC, Lam B, et al. Effects of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on image-directed planning of surgical resection for distal femoral osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1399–1405. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kan JH, Kleinman PK. Secaucus. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2010. Pediatric and Adolescent Musculoskeletal MRI: A Case-Based Approach; p. 754. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heck RK, Carnesale PG. General principles of tumors. In: Canale ST, editor. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 10. Philadelphia: Mosby, Inc; 2003. pp. 733–792. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gitelis S, Malawer M, MacDonald D, Derman G. Principles of limb salvage surgery. In: Chapman MW, editor. Chapman’s Orthopaedic Surgery. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Inc; 2001. pp. 3309–3381. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittig JC, Bickels J, Priebat D, et al. Osteosarcoma: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2002;15:65, 1123–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayer M. Parosteal osteosarcoma of the distal femur. In: Conrad EU, editor. Orthopaedic oncology: diagnosis and treatment. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc; 2009. pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada K, Frassica FJ, Sim FH, et al. Parosteal osteosarcoma. A clinicopathological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:366–378. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luck JV, Luck JV, Schwinn CP. Parosteal osteosarcoma: a treatment-oriented study. Clin Orthopaed Rel Res. 1980;153:92–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreou D, Bielack SS, Carrle D, et al. The influence of tumor- and treatment-related factors on the development of local recurrence in osteosarcoma after adequate surgery. An analysis of 1355 patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group protocols. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1228–1235. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avedian RS, Haydon RC, Peabody TD. Multiplanar osteotomy with limited wide margins: a tissue preserving surgical technique for high-grade bone sarcomas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2754–2764. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bacci G, Forni C, Longhi A, et al. Local recurrence and local control of non-metastatic osteosarcoma of the extremities: a 27-year experience in a single institution. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:118–123. doi: 10.1002/jso.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bacci G, Ferrari S, Mercuri M, et al. Predictive factors for local recurrence in osteosarcoma: 540 patients with extremity tumors followed for minimum 2. 5 years after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:230–236. doi: 10.3109/17453679809000921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picci P, Sangiorgi L, Rougraff BT, et al. Relationship of chemotherapy-induced necrosis and surgical margins to local recurrence in osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2699–2705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.12.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bramer JA, van Linge JH, Grimer RJ, Scholten RJ. Prognostic factors in localized extremity osteosarcoma: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picci P, Sangiorgi L, Bahamonde L, et al. Risk factors for local recurrences after limb-salvage surgery for high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:899–903. doi: 10.1023/a:1008230801849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bieling P, Rehan N, Winkler P, et al. Tumor size and prognosis in aggressively treated osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:848–858. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]