Abstract

Mucormycosis is an opportunistic fungal infection that is associated with high mortality in immunocompromised individuals. While rhinocerebral and pulmonary forms are most common, primary gastrointestinal mucormycosis is very uncommon. The stomach is the most commonly affected organ followed by the colon and ileum in alimentary zygomycosis. We report a rare case of invasive gastric mucormycosis in a 50-year-old diabetic gentleman with a history of chronic alcoholism presenting with complaints of pain and distension of the abdomen for 6 days associated with fever, nausea, vomiting and anorexia. At presentation, he was hemodynamically unstable, febrile with uncontrolled blood sugar level and had negative HIV serology. There was generalized guarding, rigidity and distension of the abdomen and investigations confirmed perforative peritonitis. Upon exploration, there was solitary large 4 × 4 cm size perforated ulcer in the gastric body with greenish, greyish sloughed out mucosa within. Wedge resection of the ulcer with primary closure was performed. Histopathology revealed aseptate, broad, obtuse angled fungal hyphae, and invasive mucormycosis was confirmed by special stains like Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Gomori′s methenamine silver (GMS). Very few cases of invasive gastric mucormycosis associated with uncontrolled diabetes and alcoholism have been reported in the literature. Delayed presentation of the patient along with rapid progression to fungal septicaemia resulted in the case fatality despite early surgical intervention and critical care management.

Keywords: Invasive gastric mucormycosis, Perforative peritonitis, Diabetes, Alcoholism

Introduction

Mucormycosis, although uncommon, is caused by the ubiquitous filamentous fungi and is associated with high mortality rates, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Primary gastrointestinal mucormycosis is very uncommon [1], and reported cases in adults are on the rise in conditions such as malignant haematological disease, transplant recipients, malnourishment, diabetes, neutropenia and iron-overload states [2]. Here, we report a rare case of invasive gastric mucormycosis in an uncontrolled diabetic with alcoholic liver disease presenting with perforative peritonitis.

Case Report

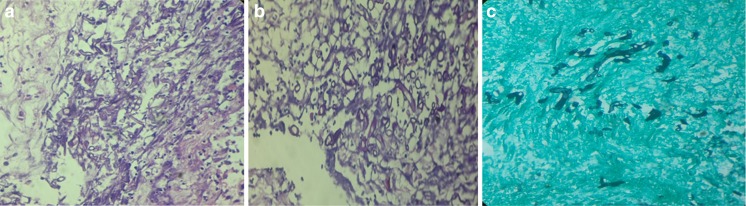

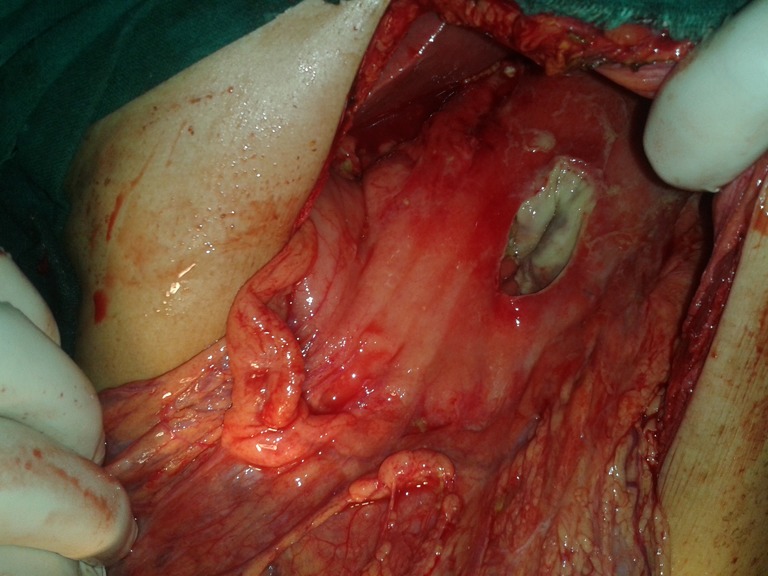

A 50-year-old diabetic gentleman presented with complaints of abdominal pain and distension for 6 days associated with fever, nausea, vomiting and anorexia. There was neither a history of haematemesis, melaena, hematochezia nor any history of trauma to the abdomen. He was a chronic alcoholic for at least 10 years and was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus only a year prior. On examination, the patient was febrile (temp = 39 °C), had tachycardia (pulse = 110 beats/min), had hypotension (BP = 90/60 mmHg), had tachypnea (RR = 26/min) and had altered mentation. Abdominal examination revealed a distended, tender abdomen with generalized guarding, rigidity and absent bowel sounds, highly suggestive of perforative peritonitis. He was negative for HIV, hepatitis B markers and his random blood sugar level at admission was 355 mg/dl with urine positive for sugars (+++), but negative for ketones. Upon stabilization, his ultrasonography revealed distended bowel loops with sluggish peristalsis, hepatomegaly and moderate free fluid. An erect abdominal X-ray confirmed free air under the diaphragm. After initial fluid resuscitation and insulin infusion, the patient was shifted to the operating room. At surgical exploration, there was solitary 4 × 4 cm circumferential perforation in the gastric body with irregular margins, 5 cm from pylorus, with sloughed out greenish, greyish gastric mucosa within [Fig. 1]. There was around 300 cm3 free fluid in the abdomen with minimal peritoneal contamination. Wedge resection of the perforated gastric ulcer with primary closure of the stomach was done followed by thorough peritoneal lavage. The patient was nursed in the intensive care unit post-operatively. On histopathology, multiple studied sections showed ulcerated mucosa and granulation tissue composed of acute on chronic inflammatory infiltrate and proliferating blood vessels. Aseptate, broad, obtuse angled fungal hyphae along with foreign body type granulomas and Langhans type giant cells were seen on haematoxylin and eosin stain [Fig. 2a]. Special stains like Periodic Acid-Schiff [PAS] confirmed the fungal morphology and Gomori′s methenamine–silver (GMS) stain showed black fungal hyphae of mucormycosis. [Fig. 2b, c]. Diagnosis of invasive gastric mucormycosis was thus confirmed. However, microbiological culture and species subtyping was not done.

Fig. 1.

Intra-operative image of the perforated gastric ulcer

Fig. 2.

a Haematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrating fungal hyphae (LPF). b PAS stain showing mucormycosis (HPF). c Gomori′s Methenamine–silver stain demonstrating branched obtuse angled fungal hyphae

Despite aggressive surgical and critical care management, the patient progressively deteriorated and died because of multi-organ failure on the second post-operative day. Post-mortem examination was not done, and we do not know if the other organs were involved. Histopathological diagnosis of the resected specimen was obtained after the patient succumbed and so specific antifungal therapy could not be instituted.

Ethics

No approval of the institutional review committee was needed because the data was collected in the course of common clinical practice, and accordingly, written informed consent was obtained before the surgical procedure. The study protocol conforms to the “World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human subjects” adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964, as revised in Tokyo 2004.

Discussion

Mucormycosis is an opportunistic angioinvasive fungal infection and results from inhalation or direct inoculation of sporangiospores onto disrupted skin or mucosa in immunocompromised individuals [1].

Rhinocerebral and pulmonary forms are most common presentations while primary gastrointestinal mucormycosis is very uncommon [1, 3]. It may occur due to ingestion of infected sputum or secondary colonization of pre-existing ulcers [5]. The stomach is the most commonly affected followed by the colon and ileum. The symptomatology of gastrointestinal mucormycosis varies, ranging from fever, non-specific abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting to hematemesis, melaena, hematochezia or gastrointestinal perforation. The diagnosis is often made histopathologically by biopsy of the suspected area at surgery or endoscopy [1, 4–7]. It is known as primary gastric mucormycosis when the stomach is the only affected site. While there have been case reports in premature neonates and malnourished children [1, 3, 4], primary gastric mucormycosis in adults is on a rise [5–7]. Non-specific symptomatology and delayed antemortem diagnosis have resulted in mortality as high as 85 % in gastrointestinal mucormycosis, primarily due to bowel perforation [3].

Uncontrolled diabetes has been a major predisposing factor for mucormycosis [1, 3, 8]. Although rhinocerebral form is most commonly associated with diabetes [3], few cases of gastric mucormycosis in diabetics have been reported [6, 7]. Alcoholic liver disease was never reported as a predisposing factor, but cases of gastric mucormycosis associated with chronic alcoholism [5, 6] and cirrhosis [7] along with other co-morbid factors have been reported.

The diagnosis of gastric mucormycosis is made on biopsy that shows aseptate, broad PAS-positive fungal hyphae adjacent to the necrotic areas. Definitive diagnosis by microbiological culture and identification of the causative organism to the genus and species carries valuable epidemiological, therapeutic and prognostic implications. Polyene antifungal agent, amphotericin B, is typically active against the fungus, and liposomal formulations have been effective due to less nephrotoxicity. The role of combination antifungal therapy is uncertain [1]. However, antifungal therapy alone is typically inadequate, and surgery to debulk or resect all infected tissue is often required for an effective cure. Roden et al. [3], in his review, has confirmed the importance of multimodality treatment with surgery and amphotericin B.

Knowledge about this fungal pathogen and its clinic-pathological spectrum will certainly benefit clinicians in early diagnosis and management of this disease entity. A strong clinical suspicion and diagnosis and aggressive surgical debridement with adjunct amphotericin B therapy are essential to avert fatalities associated with the disease.

In our case, invasive gastric mucormycosis was associated with uncontrolled diabetes and chronic alcoholism, leading to a fatal outcome. Colonization of gastric erosions due to chronic alcoholism with subsequent wall invasion could be a possibility. Delayed presentation after 6 days of onset of symptoms and lack of immune response from the patient, as indicated by minimal peritoneal contamination at laparotomy, resulted in rapid progression to fungal septicaemia. Despite early surgical intervention after presentation, the patient could not be salvaged. We do not know if it was primary gastric mucormycosis or gastric manifestation of a systemic mycosis, as post-mortem examination was not done. Jung et al. [6] report a similar case of invasive gastric mucormycosis associated with emphysematous gastritis in alcoholic and diabetic patient who had a lethal outcome.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

None

Financial Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Spellberg B. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis: an evolving disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:140–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:23–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, Sein M, Sein T, Chiou CC, Chu JH, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–53. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhury M, Kahkashan E, Choudhury SR. Neonatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis—a case report. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:81–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahapure AG, Patankar RV, Bhatkhande R. Gastric mucormycosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2002;21:231–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung JH, Choi HJ, Yoo J, Kang SJ, Lee KY. Emphysematous gastritis associated with invasive gastric mucormycosis: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:923–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.5.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dannheimer IP, Fouche W, Nel C. Gastric mucormycosis in a diabetic patient. S Afr Med J. 1974;48:838–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakrabarti A, Das A, Mandal J, et al. The rising trend of invasive mucormycosis in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Med Mycol. 2006;44:335–42. doi: 10.1080/13693780500464930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]