Abstract

Rationale

Higher doses of benzodiazepines and alcohol induce sedation and sleep; however, in low to moderate doses these drugs can increase aggressive behavior.

Objectives

To assess firstly the effects of ethanol, secondly the effects of flunitrazepam, a so-called club drug, and thirdly the effects of flunitrazepam plus alcohol on aggression in mice and rats.

Methods

Exhaustive behavioral records of confrontations between a male resident and a male intruder were obtained twice a week, using CF-1 mice and Wistar rats. The salient aggressive and non-aggressive elements in the resident´s reperetoire were analyzed. Initially, the effects of ethanol (1.0 g/kg), and secondly flunitrazepam (0; 0.01; 0.1; and 0.3 mg/kg) were determined in all mice and rats; subsequently, flunitrazepam or vehicle, given intraperitoneally (0; 0.01; 0.1; and 0.3 mg/kg) was administered plus ethanol 1.0 g/kg or vehicle via gavage.

Results

The most significant finding is the escalation of aggression after a moderate dose of ethanol, and a low dose of flunitrazepam. The largest increase in aggressive behaviour occurred after combined flunitrazepam plus ethanol treatment in mice and rats.

Conclusions

Ethanol can heighten aggressive behavior and flunitrazepam further increases this effect in male mice and rats.

Keywords: benzodiazepines, GABAA receptor, aggression, club drug, alcohol

Introduction

Gabaergic mechanisms are implicated in several forms of behavioral and physiological disinhibition (Bond and Lader 1991; Stephens et al 2005), impulsivity (Bizot et al. 1999) and heightened aggressive behavior (Fox and Snyder, 1969, Apfelbach and Delgado 1974; Krsiak 1979; Miczek and O'Donnell, 1980; Puglisi-Allegra et al. 1981; Miczek et al. 2003; Gourley et al. 2005; De Almeida et al. 2008).

Studies on the effect of GABA(A) receptor modulators including allopregnanolone and pregnanolone, both neuroactive metabolites of progesterone, as well as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and alcohol (for review see Kumar, 2009) have shown divergent results. Although human and animal studies have revealed beneficial properties such as anaesthesia, sedation, anticonvulsant effects, and anxiolytic effects; however the reports have also indicated adverse effects such as anxiety, irritability, and aggression, particularly at lower doses (for review see Andréen et al 2009).

In preclinical studies the administration of low to moderate doses of allosteric positive modulators of the GABAA receptor leads to significant increases in aggressive behavior (Miczek 1974; Rodgers and Waters 1985; Mos and Olivier 1989; Fish et al. 2001; Miczek et al. 2003; De Almeida et al. 2004; Gourley et al. 2005). Experiments in humans and clinical observations confirmed these high levels of aggression in some individuals after using benzodiazepines (BZDs) (diMascio 1972; Ben-Porath and Taylor 2002) or alcohol intake in low to moderate doses (Bond et al 1998), particularly after tolerance to the sedative effects has developed.

Alcohol more than any other drug has been associated with aggressive and violent behavior (Miczek et al 2004). The development of an experimental procedure to model heightened aggressive behavior after consumption of alcohol has facilitated the neurobiologic analysis of the link between alcohol and aggression (Miczek et al. 1992; Miczek and De Almeida 2001). From a pharmacologic perspective, consumption of low to moderate doses of alcohol engenders heightened aggressive behavior in a significant number of individuals preceding the circulation of appreciable amounts of the aldehyde metabolite (Miczek et al. 1998). Ionophoric receptors such as NMDA, 5-HT(3) and GABA(A) have been identified in the brain as major sites of action for alcohol in the dose range that is relevant for engendering heightened aggression (Grant and Lovinger 1995). Actions at the GABA(A) receptor complex that depend on particular GABA(A) subunit composition appear to be necessary for alcohol-heightened aggression (Miczek et al 2003). Benzodiazepines, specifically when associated with alcohol, seem to facilitate GABAergic transmission, which can be the source for the disinhibited behaviors (Saïas and Gallarda, 2008). Individuals who abuse flunitrazepam often commit sexual assaults and violent acts (Dåderman and Lidberg 1999). The increasing abuse of MDMA, flunitrazepam, and ketamine hydrochloride, have been seen particularly by young people in social settings such as clubs. Most of the time they take flunitrazepam together with alcohol and exhibit euphoria, agitation and amnesia (Druid et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2002). Flunitrazepam is becoming increasingly abused by the young who use this drug in combination with alcohol and commit violent crimes (Daderman et al 2002). In addition to the unknown mechanisms via which cultural factors link flunitrazepam, alcohol and violence, there are common targets for both drugs on the GABAA receptor that may contribute to the display of increased aggressive behavior.

We assessed the acute effects of alcohol on aggressive behavior in male resident mice and rats at a previously determined maximally effective dose, and the effects after administration of flunitrazepam in combination with alcohol in rats and mice, the former living in colonies, the latter most often dispersing in territories (Miczek et al. 2003; Miczek and de Boer 2005). We focused on aggressive behavior by residents confronting an intruder, as this type of aggression is heightened by alcohol and BZDs and particularly the combination of both drugs (Miczek 1974; Miczek and Barry 1977; Miczek and O'Donnell 1980; Miczek et al. 1992).

Methods

Subjects

Male CF1 mice (Mus musculus) (n=28) obtained from (FEPPS, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil) were used as residents and as intruders (n=64) in the experiments. At the start of the experiment, the resident male mice were 60 days old, weighing 25 g, and housed as breeding pairs. Each resident was housed in clear polycarbonated cages (28× 17 × 14 cm) with a female (n=28) from the same strain. Intruders were from the same strain, weighting 25-40 g, 50 days old and maintained in groups of eight, in standard polycarbonate boxes (46 × 24 × 15 cm). All mice were in the same vivarium according to a 12:12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00 hours), in a temperature-controlled environment (20 ± 2 ° C) with food and water available ad libitum. The animals were tested during the light phase of the photo cycle from 09:00 to 16:00 hours in order to avoid high baseline levels of fighting.

Male Wistar rats, obtained from (FEPPS, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil), were established as residents (n=10) confronting intruders (n=30) (Miczek 1979). The resident male rats were 150 days old, weighing between 380-450 g and housed as breeding pairs in plastic cages (www.beiramar.com GK 115, 49×34×21cm). The animals were provisioned with food and water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 5:00 a.m.). The intruders weighed between 350-420 g and were kept in groups of 6 animals per cage (www.beiramar.com GK 115, 49 × 34× 16 cm). Animals were tested from 5 pm to 7 pm twice a week with at least 72 hours between tests during the dark-phase of the cycle.

The female cohabitant was removed during the behavioral tests, and the male rats were repeatedly tested in advance to establish the aggressive behavior towards a male intruder.

All animals were cared for in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and Colégio Brasileiro de Experimentação Animal (COBEA) and the protocol was accepted.

Resident-intruder confrontations

Resident males were allowed to acclimate for 21 days with their female cagemate in the laboratory environment. After this period, each resident was submitted to successive confrontations with a male intruder (3 times a week with intervals of at least 24 h) to establish the baseline of aggressive behavior. Before these tests, the female and pups were removed and a male intruder was placed into the home cage of the resident. Each behavioral test lasted 5 minutes and if no attack bite occurred, the experimental session was terminated after 5 minutes (Miczek and O'Donnell 1978). Only the animals that exhibited more than 10 bites per 5 min were included in the experiment. In the rare cases when the resident was attacked, the intruder was substituted immediately. In confirmation of earlier observations (Winslow and Miczek 1984) the levels of aggression from the resident mice were more variable during the first confrontations than after some six or seven baseline confrontations with the same intruder.

Experimental Procedure

Firstly, the mice and rats were administered with ethanol (1.0 g/kg) or vehicle via gavage (mice, n= 28 and rats, n=10) before the behavioral test. Each animal received ethanol three times at 1.0 g/kg and three times or more the vehicle, ensuring stable fighting after vehicle control treatment.

Secondly, a flunitrazepam dose-effect determination (0.01; 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) was performed in male mice (n=28) and in male rats (n=10), each dose given in a counterbalanced sequence to the individual animals intraperitoneally (ip).

Thirdly, the mice and rats were administered ip with flunitrazepam (0.01; 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) plus ethanol (1.0 g/kg) via gavage (mice, n= 28 and rats, n=10). The animals were injected with flunitrazepam or vehicle ip 30 minutes and with alcohol or vehicle (water) via gavage 15 minutes before the behavioral test for aggression towards a male intruder.

Drugs

Ethanol was prepared by diluting 95% ethanol to 10.0% (w/v) with distilled water and was administered orally via gavage 15 minutes before the behavioral test. The 1.0 g/kg dose of ethanol was chosen because it is the maximally effective low dose which escalates aggression in mice and rats (see Miczek et al. 1992; Miczek et al. 1998; Miczek and De Almeida 2001; Van Erp and Miczek 2007).

Flunitrazepam was prepared in a 5% Tween 80 water solution. Drug doses were counterbalanced between subjects. The drug or vehicle was injected ip in a volume of 1.0 ml/100 g in mice, and 1.0 ml/kg in rats, 30 minutes prior to the confrontation with the intruder.

Resident-intruder confrontations in mice

Resident males were allowed to acclimate for 21 days with their female cagemate in the laboratory environment. After this period, each resident was submitted to successive tests (3 times a week, each test separated by at least 24 h) to establish a stable baseline of aggressive behavior. Before each test, female and pups were removed and a male intruder was placed into the home cage of residents. Each behavioral test lasted 5 minutes and if no attack bite occurred, the experimental session was terminated after 5 minutes (Miczek and O´Donnell 1978). Only the animals that delivered more than 10 bites per 5 min were included in the experiment. In the rare cases when the resident was attacked, the intruder was substituted immediately. After six or seven confrontations the level of aggressive behavior toward the intruder became more stable (Winslow and Miczek 1984).. The behaviors were analyzed blind with regard to the treatment condition.

Resident-intruder confrontations in rats

The behaviors of the male resident towards a male intruder were recorded on videotape during the 10 min confrontations twice a week during the dark phase. A trained observer used the “Observer” program (Noldus, Wageningen, The Netherlands) to analyze the following salient aggressive behaviors: attack bites, sideways threats, aggressive postures, pursuits, pins and nips, and non-aggressive elements such as: walking, rearing, autogrooming, and digging. These behavioral elements are operationally defined and illustrated by Miczek and de Boer (2005). The frequency and the duration of these behavioral acts and postures were analyzed. In rats, the measure of total aggression was calculated as the sum of the frequency counts for bites + sideways threats + pin + nip. This approach reduced the impact of large individual differences in the display of these four elements of aggressive behavior (de Almeida et al. 2008). The behaviors were analyzed blind with regard to the treatment condition.

Statistical Analysis

Durations and frequencies of all salient aggressive and non-aggressive behaviors were recorded. All data were expressed as mean ±SEM. Regarding non-aggressive motor behaviors, the data from all groups were compared with those from their respective controls using ANOVA. When significant differences were found, Bonferroni post hoc tests were performed. Firstly, the effects of ethanol were analyzed and compared between vehicle (water) and 1g/kg ethanol. Ethanol data were analyzed comparing treated and control (vehicle) group. Post hoc analyses were carried out using the Student t Test, with the level of significance set at p< 0.05.

Secondly, the effects of flunitrazepam (0.01-0.3) were separately analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When there were statistically significant F values (p≤0.05), Bonferroni post hoc tests compared drug treatments with the corresponding vehicle group. And thirdly, the effects of flunitrazepam plus alcohol on aggression in mice and rats were assessed. The interaction between ethanol and flunitrazepam effects was analyzed, particularly, the comparison of flunitrazepam and ethanol by itself and with the combined treatment, using an ANOVA and when a statistically significant effect was present post hoc Tukey tests were used to compare individual drug doses to vehicle baseline. The level of significance was set at p< 0.05.

Results

Ethanol effects on aggression in mice and rats

Oral administration of the 1.0 g/kg ethanol dose significantly increased aggressive behaviour in male mice as compared to the values after vehicle treatment (t(27)=3.92; p<0.001; Fig. 1, part A). And the same dose increased the aggression in the male rats as compared to the values after vehicle treatment, (t(9)=2.55; p<0.02; Fig.1, part B). In Figure 2 the frequency of aggressive behaviour by each individual mouse and rat are rank-ordered according to their size after treatment with water vs. ethanol.

Figure 1.

A Frequency of aggression in male mice (n=28) and B frequency of aggression in male rats (n=10) administered 3 times with vehicle or 1.0 g/kg ethanol each. Vertical bars represent the mean ± SEM and asterisks indicate the statistical difference between the groups, p≤ 0.05.

Figure 2.

Histogram rank-ordering the bars according to the frequency of aggressive behaviour after water (clear bars) vs. ethanol (grey bars) in individual male mice (n=28) in A, and male rats (n=10) in B.

Ethanol effects on non-aggressive behavior in mice and rats

After the administration of ethanol (1.0 g/kg) in mice and rats none of the elements of non-aggressive behaviour such as walking, rearing and grooming revealed any significant effects as compared to the vehicle treatment condition.

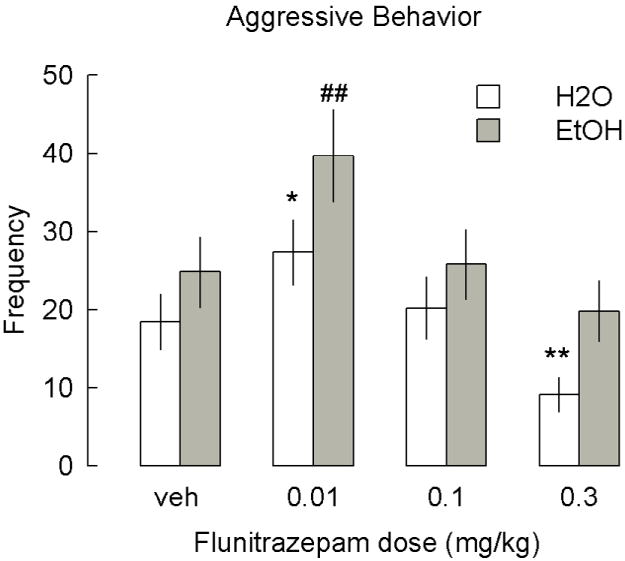

Flunitrazepam effects on aggression

The low 0.01 mg/kg dose of flunitrazepam increased significantly aggressive behavior in resident mice and rats relative to vehicle values [F(7,164)=6.28, p< 0.00004] (Figure 3, part A). By contrast, after administration with 0.3 mg/kg flunitrazepam, the resident rats displayed less aggressive behaviour [F(7,164)=5.42 (p<0.000006)] relative to the values in the vehicle condition (Figure 3, part B).

Figure 3.

A Frequency of aggression in resident male mice (n=28) and the right side of the figure shows the effects of flunitrazepam (0.01-0.3 mg/kg) and the left side the effects of ethanol 1.0 g/kg plus flunitrazepam (0.01-0.3 mg/kg). B Frequency of aggression in resident male rats (n=10). The frequency of attack bites towards the male intruder are depicted. Vertical bars represent the mean ± SEM and * statistical difference from vehicle; ## statistical difference from all other groups, p≤ 0.05.

Flunitrazepam plus ethanol effects on aggression

The low 0.01 mg/kg dose of flunitrazepam plus 1.0 g/kg ethanol significantly increased aggressive behavior [F(7,164)=7.82, p< 0.00003] in male mice as compared to the measures after vehicle treatment. However, the higher dose of flunitrazepam 0.3 mg/kg plus 1.0 g/kg ethanol decreased aggression in mice [F(7,164)=1.71, p< 0.01 (Figure 3). Also, the lower dose of 0.01 mg/kg of flunitrazepam plus ethanol 1.0 g/kg significantly increased aggressive behavior [F(7,164)=5.20 (p<0.0001)] in male rats as compared to vehicle group. This increase in aggressive behavior was significantly larger than that in the group treated with 0.01 mg/kg flunitrazepam only. An overall two-way ANOVA analysis (treatments versus doses) compared the data from all groups treated with flunitrazepam (0.0; 0.01; 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) and ethanol 1.0 g/kg and water vehicle [F(7,164)=6.28, p<0.000004]. As expected, the ethanol 1.0 g/kg dose increased aggression. The lowest dose of flunitrazepam tested increased aggression in both species. For the combinations, the lowest dose of flunitrazepam plus ethanol further increased significantly aggression.

Flunitrazepam effects on non-aggressive behavior

In mice, ip administration of flunitrazepam did not alter the display of the elements of non-aggressive behavior such as walking, rearing and grooming as compared to vehicle treatment (Table 1). In rats, the high 0.3 mg/kg dose of flunitrazepam decreased the duration of walking [F(7,164)=3.29, (p<0.009) and increased the duration of lying [F(7,164)= 2.69, p<0.02] indicative of sedative effects (Table 2). The other individual elements of non-aggressive behavior did not show any significant effects after flunitrazepam administrations as compared to vehicle control.

Table 1.

Frequency of aggressive behaviors and duration of non-aggressive behaviors (in seconds) by the resident mice (n=28) towards a male intruder during 5 minute behavioral tests. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

| Flunitrazepam (mg/kg) | Ethanol + Flunitrazepam (mg/kg) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Frequency | V +V | V+0.01 | V+0.1 | V+0.3 | E+V | E+0.01 | E+0.1 | E+0.3 |

| Sideways threat | 20.6±1.9 | 26.6±6.8 | 25.7±2.8 | 25.1±1.4 | 30.2±3.7 | 26.6±3.8 | 14.5±2.9* | 24.8±3.8 |

| Sniff | 6.3±1.4 | 12.6±2.5 | 14.3±2.7 | 11.7±2.9 | 11.1 ±3.2 | 4.7±0.8 | 13.5±3.6 | 6.4±3.1 |

| Tail rattle | 11.8±1.5 | 5.1±2.0 | 8.1 ±2.0 | 9.5±2.6 | 14.5±3.4 | 17.1 ±4.1 | 20.9±4.0 | 23.5±6.7 |

|

| ||||||||

| Duration | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Groom (s) | 6.6±1.3 | 2.3±1.2 | 4.1 ±0.8 | 3.2±0.9 | 17.1±4.3 | 21 3±5.2 | 26.3±7.2 | 13.0±4.4 |

| Rear (s) | 13.9±4.7 | 5.6±1.5 | 9.0±2.6 | 3.0±0.8 | 20.3±7.1 | 22.1±10.5 | 12.2±3.0 | 40.7±21.0 |

| Walk (s) | 69.2±11.7 | 74.2±5.4 | 81.2±20.1 | 57.6±12.2 | 75.2±3.4 | 74.3±5.4 | 72.7±5.1 | 64.3±15.3 |

V=Vehicle; E=Ethanol

Table 2.

Frequency of aggressive behaviors and duration of non-aggressive behaviors (in seconds) by the resident rats (n=10) towards a male intruder during 10 minute behavioral tests. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

| Flunitrazepam (mg/kg) | Ethanol + Flunitrazepam (mg/kg) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Frequency | V +V | V+0.01 | V+0.1 | V+0.3 | E+V | E+0.01 | E+0.1 | E+0.3 |

| Lateral threat | 10.6±1.9 | 6.6±2.8 | 5.7±2.8 | 5.1 ±1.4 | 13.0±3.7 | 16.6±4.1 | 17.5±3.5* | 14.8±3.8 |

| Sniff | 16.8±4.6 | 22.7±5.5 | 24.8±5.3 | 21.9±6.1 | 21.4±5.4 | 24.6±5.2 | 23.8±4.9 | 26.2±5.4 |

|

| ||||||||

| Duration | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Groom (s) | 6.6±1.3 | 2.3±1.2 | 4.1 ±0.8 | 3.2±0.9 | 17.1±4.3 | 21 3±5.2 | 26.3±7.2 | 13.0±4.4 |

| Rear (s) | 13.9±4.7 | 5.6±1.5 | 9.0±2.6 | 3.0±0.8 | 20.3±7.1 | 22.1±10.5 | 12.2±3.0 | 40.7±21.0 |

| Lying (s) | 47.2±11.4 | 48.5±14.4 | 58.8±19.1 | 97.8±23.8* | 34.3±5.4 | 32.7±5.1 | 34.3±5.3 | 34.3±5.3 |

| Walking (s) | 70.1±6.9 | 75.8±7.5 | 68.8±3.9 | 48.3±10.2* | 79.2±7.3 | 69.3±4.5 | 71.8±5.7 | 64.5±15.4 |

V=Vehicle; E=Ethanol;

p<0.05

Flunitrazepam plus ethanol effects on non-aggressive behavior

After the administration of flunitrazepam plus ethanol (1.0 g/kg) in mice (Table 1) and rats (Table 2) none of the elements of non-aggressive behaviour such as walking, rearing and grooming revealed any significant changes relative to those after vehicle treatment.

Discussion

The most significant finding of the current experiments is the very high level of aggressive behavior after the combined treatment with a moderate dose of ethanol plus a low dose of flunitrazepam in mice and rats. Also, the present experiments confirmed that the 1.0 g/kg dose of ethanol can significantly increase aggressive behaviour in male mice and male rats as compared to the values after vehicle treatment, although this latter effect is usually only seen in a subgroup of subjects.

Administration of flunitrazepam and ethanol did heighten aggression, both in rats and mice. One type of drug interaction occurs at low doses of both of these drugs. Acute low doses of both drugs can exert pro-aggressive effects, and these interactive effects may be due to positive modulation of the GABA(A) receptor.

A second type of drug interaction occurred at the highest dose of flunitazepam when combined with ethanol. The suppression of aggressive behavior and walking at the highest dose of flunitrazepam was apparently reversed in rats when combined with ethanol. Similarly, the highest dose of flunitrazepam decreased aggression in mice relative to vehicle only when combined with ethanol. In drug interaction studies it is important to compare shifts in dose response functions for the drugs used in combination.

In pre-clinical studies, low doses of BZDs show so-called paradoxical effects like insomnia, agitation and heightened aggression (Miczek 1974; Ben-Porath and Taylor 2002; Gourley et al. 2005; de Almeida et al 2008) and alcohol can increase aggression in a significant minority of individuals (Miczek et al. 1992, 1998; Van Erp and Miczek 1997, de Almeida et al 2004, Grant et al 2005, van Erp and Miczek 2007; Fish et al 2008).

The BZDs have been reported to disinhibit behavior in conflict models in numerous studies (e.g., Geller et al 1960; Vogel et al. 1971; Millan 2003) and these effects extend to flunitrazepam (Svensson et al. 2003). Different effects of allosteric positive modulators of GABAA receptors may be explained by targeting different subunits of the GABAA receptor complex. The α1 subunit protein and its role in aggressive behavior was investigated pharmacologically due to the availability of α1-preferring agonists, such as zolpidem and antagonists such as β-CCt and 3-PBC (Cox et al. 1995; Huang et al. 2000). The α1 subunit appears relevant in the aggression-heightening effects of midazolam and alcohol, since these effects can be attenuated by the alpha1 subunit-preferring antagonists (de Almeida et al. 2004; Gourley et al. 2005). However, future studies possibly with the recently developed point-mutated animals need to determine which subunit composition is required for flunitrazepam and alcohol to heighten aggressive behavior.

For the mediation of escalated aggressive behavior, important evidence points to the prefrontal cortex as a critical site which controls impulsive aggression (Blair 2004). We hypothesize that flunitrazepam plus alcohol may impair the neural circuit that includes in part BZD binding sites in the prefrontal cortex and which in turn leads to inhibitory dysregulation in this specific brain area (de Almeida et al. 2008). Further studies with measurements of GABA and glutamate and their receptors in the prefrontal cortex would provide a direct test of this hypothesis.

Recently Sustková-Fišerová et al (2009) studied neurochemically individually-housed male mice which behaved aggressively during encounters with strange males, while others were timid or sociable in the same situation. One week after the categorization as aggressive, timid or sociable, by means of the social conflict test, levels of glutamate, aspartate, and GABA were measured by in vivo microdialysis of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of the isolated and group-housed mice. The results showed that sociable mice had almost triple the levels of GABA in their mPFC than aggressive or timid mice. No significant differences in aspartate and glutamate levels were found in these three types of individually-housed mice. Forebrain chemistry of group-housed mice did not differ from that of individually-housed mice with the exception of levels of glutamate and GABA which were significantly lower in group-housed mice than in sociable individually-housed mice. These results suggested that GABA might play a role in the shift from aggressive behavior to sociable behavior, and it corroborates other findings indicating that the corticolimbic GABAergic system, interacting with serotonin, represents an important molecular and neural substrate for the selective attenuation of aggression (Sustková-Fišerová et al 2009).

In conclusion, flunitrazepam at low doses and flunitrazepam plus alcohol engender very high levels of aggression when administered in mice and rats. We postulate that flunitrazepam in combination with alcohol causes impulsive behavior due to the loss of control and the benzodiazepines reduce 5-HT neurotransmission, which precipitate aggressive behavior.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andréen L, Nyberg S, Turkmen, van Wingen G, Fernández G, Bäckström T. Sex steroid induced negative mood may be explained by the paradoxical effect mediated by GABA(A) modulators. Psychoneurol. 2009;34(8):1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfelbach R, Delgado J. Social hierarchy in monkeys (Macaca mulatta) modified by chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride. Neuropharmacol. 1974;13:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(74)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath D, Taylor S. The effects of diazepam (valium) and aggressive disposition on human aggression: an experimental investigation. Addict Behav. 2002;27:167–77. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizot J, Le Bihan C, Puech AC, Hamon M, Thiébot M. Serotonin and tolerance to delay of reward in rats. Psychopharmacol. 1999;146(4):400–12. doi: 10.1007/pl00005485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behavior. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:198–208. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A, Lader M. Does alcohol modify responses to reward in a competitive task? Alcohol Alcohol. 1991;26(1):61–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A, Curran H, Bruce M, O'Sullivan G, Shine P. Behavioural aggression in panic disorder after 8 weeks' treatment with alprazolam. J Affect Disord. 1998;35:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox ED, Hagen TJ, McKernan RM, Cook JM. BZ1 receptor subtype specific ligands: synthesis and biological properties of β-CCt, a BZ1 receptor subtype specific antagonist. Med Chem Res. 1995;5:710–718. [Google Scholar]

- Dåderman AM, Lidberg L. Flunitrazepam (Rohypnol) abuse in combination with alcohol causes premeditated, grievous violence in male juvenile offenders. J AM Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(1):83–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dåderman AM, Fredriksson B, Kristiansson M, Nilsson LH, Lidberg L. Violent behavior, impulsive decision-making, and anterograde amnesia while intoxicated with flunitrazepam and alcohol or other drugs: a case study in forensic psychiatric patients. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):238–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida RMM, Rowlett JK, Cook JM, Yin W, Miczek KA. GABAA/alpha1 receptor agonists and antagonists: effects on species-typical and heightened aggressive behavior after alcohol self-administration in mice. Psychopharmacol. 2004:172, 255–63. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida RMM, Benini Q, Betat JS, Hipólide DC, Miczek KA, Svensson IA. Heightened aggression after chronic flunitrazepam in male rats: Potential links to cortical and caudate-putamen binding sites. Psychopharmacol. 2008;197(2):309–18. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMascio A. The effects of benzodiazepines on aggression: reduced or increased. Psychopharmacol. 1972;30:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00421423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druid H, Holmgren P, Ahlner J. Flunitrazepam: an evaluation of use, abuse and toxicity. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;122(2-3):136–41. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish EW, Faccidomo S, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Alcohol, allopregnanolone and aggression in mice. Psychopharamcol. 2001;153(4):473–83. doi: 10.1007/s002130000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JR, Mckenzie-Quirk SD, Bannai M, Miczek KA. 5-HT(1B) receptor inhibition of alcohol-heightened aggression in mice: comparison to drink and running. Psychopharmacol. 2008;197(1):145–56. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K, Snyder R. Effect of sustained low doses of diazepam on aggression and mortality in grouped male mice. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1969;69:663–6. doi: 10.1037/h0028190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller I, Demarco AO, Seiftner J. Delayed effects of nicotine on timing behavior in the rat. Science. 1960:131, 735–7. doi: 10.1126/science.131.3402.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourley S, Debold J, Yin W, Cook J, Miczek KA. Benzodiazepines and heightened aggressive behavior in rats: reduction by GABA(A)/alpha(1) receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacol. 2005;178:232–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Lovinger DM. Cellular and behavioral neurobiology of alcohol-receptor-mediated neuronal processes. Clinical Neuroscience. 1995;3:155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, He X, Ma C, Liu R, Yu S, Dayer CA, Wenger GR, McKernan R, Cook JM. Pharmacophore/receptor models for GABA(A)/BzR subtypes (alpha1beta3gamma2, alpha5beta3gamma2, and alpha6beta3gamma2) via a comprehensive ligand-mapping approach. J Med Chem. 2000:43, 71–95. doi: 10.1021/jm990341r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krsiak M. Effects of drugs on behaviour of aggressive mice. Br J Pharmacol. 1979;65:525–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1979.tb07861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Porcu P, Werner DF, Matthews DB, Diaz-Granados JL, Helfand RS, Morrow L. Psychopharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1562-z. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA. Intraspecies aggression in rats: effects of d-amphetamine and chlordiazepoxide. Psychopharmacol. 1974;39:275–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00422968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Barry H., 3rd Effects of alcohol on attack and defensive-submissive reactions in rats. Psychopharmacol. 1977;52:231–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00426705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA. A new test for aggression in rats without aversive stimulation: Differential effects of d-amphetamine and cocaine. Psychopharmacol. 1979;60:253–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00426664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, O'Donnell J. Intruder-evoked aggression in isolated and nonisolated mice: effects of psychomotor stimulants and L-dopa. Psychopharmacol. 1978;57(1):47–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00426957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, O'Donnell J. Alcohol and chlordiazepoxide increase suppressed aggression in mice. Psychopharmacol. 1980;69:39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00426519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Weerts EM, DeBold J, Vatne T. Alcohol and “bursts” of aggressive behavior: Ethological analysis of individual differences in rats. Psychopharmacol. 1992:107, 551–563. doi: 10.1007/BF02245270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Barros HM, Weerts EM. Alcohol and heightened aggression in individual mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1698–1705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, de Almeida RMM. Oral drug self-administration in the home cage of mice: alcohol-heightened aggression and inhibition by the 5-HT1B agonist anpirtoline. Psychopharmacol. 2001;157:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s002130100831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek K, Fish E, De Bold J. Neurosteroids, GABAA receptors, and escalated aggressive behavior. Horm Behav. 2001;44:242–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Fish EW, de Almeida RMM, Faccidomo S, DeBold JF. Role of alcohol consumption in escalations to violence. In: Devine J, Gilligan J, Miczek KA, Pfaff D, Shaikh R, editors. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 1036. 2004. pp. 278–289. Youth Violence. Scientific Approaches to Prevention. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Progress in Neurobiol. 2003;70:83–244. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mos J, Olivier B. Quantitative and comparative analyses of pro-aggressive actions of benzodiazepines in maternal aggression of rats. Psychopharmacol. 1989;97(2):152–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00442238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi-Allegra S, Simler S, Kempf E, Mandel P. Involvement of the GABAergic system in shock-induced aggressive behavior in two strains of mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981;14(Suppl 1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(81)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JR, Waters A. Benzodiazepines and their antagonists: a pharmacoethological analysis with particular reference to effects on “aggression”. Neurosci Biobehav. 1985;Rev 9:21–35. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(85)90029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saïas T, Gallarda T. Paradoxical aggressive reactions to benzodiazepine use: a review. Encephale. 2008;34(4):330–6. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM, Larive LL, Romanelli F. Club drugs: methylenedioxymethamphetamine, flunitrazepam, ketamine hydrochloride, and gamma-hydroxybutyrate. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(11):1067–76. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.11.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson A, Akesson P, Engel J, Soderpalm B. Testosterone treatment induces behavioral disinhibition in adult male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DN, Pistovcakova J, Worthing L, Atack JR, Dawson GR. Role of GABAA alpha5-containing receptors in ethanol reward in the effects of targeted gene deletion, and a selective inverse agonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;(1-3):240–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sustková-Fiseová M, Vávrová J, Krsiak M. Brain levels of GABA, glutamate and aspartate in sociable, aggressive and timid mice: an vivo microdialysis study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30(1):79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Erp AMM, Miczek KA. Increased aggression after ethanol self-administration in male resident rats. Psychopharmacol. 1997;131:287–295. doi: 10.1007/s002130050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Erp AM, Miczek KA. Increased accumbal dopamine during daily alcohol consumption and subsequent aggressive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacol. 2007;191(3):679–88. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel JR, Beer B, Clody DE. Simple and reliable conflict procedure for testing anti-anxiety agents. Psychopharmacol. 1971;21:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00403989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Miczek KA. Habituation of aggressive behavior in mice: A parametric study. Aggress Behav. 1984:10, 103–113. [Google Scholar]