Abstract

Background

Postoperative pulmonary and non-pulmonary complications are common problems that increase morbidity and mortality in surgical patients, even though the incidence has decreased with the increased use of protective lung ventilation strategies. Previous trials have focused on standard strategies in the intraoperative or postoperative period, but without personalizing these strategies to suit the needs of each individual patient and without considering both these periods as a global perioperative lung-protective approach. The trial presented here aims at comparing postoperative complications when using an individualized ventilatory management strategy in the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods with those when using a standard protective ventilation strategy in patients scheduled for major abdominal surgery.

Methods

This is a comparative, prospective, multicenter, randomized, and controlled, four-arm trial that will include 1012 patients with an intermediate or high risk for postoperative pulmonary complications. The patients will be divided into four groups: (1) individualized perioperative group: intra- and postoperative individualized strategy; (2) intraoperative individualized strategy + postoperative continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP); (3) intraoperative standard ventilation + postoperative CPAP; (4) intra- and postoperative standard strategy (conventional strategy). The primary outcome is a composite analysis of postoperative complications.

Discussion

The Individualized Perioperative Open-lung Ventilatory Strategy (iPROVE) is the first multicenter, randomized, and controlled trial to investigate whether an individualized perioperative approach prevents postoperative pulmonary complications.

Trial registration

Registered on 5 June 2014 with identification no. NCT02158923.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13063-015-0694-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Postoperative pulmonary complications, Open lung approach, Recruitment maneuvers, Positive end-expiratory pressure, Continuous positive airway pressure, Lung protective ventilation

Background

Every year more than 230 million patients are scheduled for surgical procedures that require general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation [1], and these produce postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) that increase morbidity and mortality [2-7]. There are several reasons for the appearance of PPCs related to general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation: first, cyclic alveolar recruitment/derecruitment related to atelectasis, which appears in almost all patients during general anesthesia; second, alveolar overdistension related to the use of high tidal volume (VT) or inadequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) levels [8,9]. Even for short time periods, both these factors increase the alveolar and systemic inflammatory response, thus favoring lung injury [10,11] and multiple-organ system failure [12].

Protective ventilation with a low VT and adequate PEEP prevents lung injury and decreases morbi-mortality in critically ill patients with [13-15] or without [16] previous lung injury; this has also been shown for short-term intraoperative mechanical ventilation [17], as supported by evidence from two separate meta-analyses [18,19]. An intraoperative VT of 6–8 ml/kg, together with a PEEP of 6–8 cmH2O, decreases PPCs, readmissions, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS), and even mortality, compared to ventilation with a VT of 10 ml/kg and a PEEP of 3 cmH2O [19]. Despite a significant decrease in the number of PPCs, they are still high in intermediate- and high-risk patients [18-20]. We hypothesize that this may be either because one standard protective strategy does not fit all patients or because a global approach, including a combined intraoperative and postoperative strategy, is required to minimize postoperative complications in these patients.

Lung injury has also been attributed to a high fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) by, among other phenomena, increasing the number of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which has raised concerns about the potential harm of perioperative hyperoxia [21]. In spite of this, we propose the use of 0.8 FiO2 intraoperatively for optimal care for several reasons. First, even though some studies have suggested that a high VT and hyperoxia have a synergistic effect that accentuates alveolar damage, lung-protective ventilation may substantially reduce additional risks from hyperoxia. The use of PEEP as well as protective mechanical ventilation (MV) has substantially reduced the risk related to hyperoxia for the vast majority of patients requiring MV [22]. Second, tissue hyperoxia decreases oxidative stress related to perioperative ischemia/reperfusion phenomena, an effect that has been demonstrated in colon, thoracic, and cardiac surgery [23]. Third, the use of a FiO2 of 0.8 during anesthesia has been shown to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs) in many surgical procedures [24], with an SSI risk reduction of 23% for all surgeries combined [25], and therefore the rationale for proposing hyperoxia as a factor in preventing SSIs is well established [26]. Finally, hyperoxia does not seem to increase atelectasis or other pulmonary complications after surgical procedures [24].

Complementary strategies for lowering VT and PEEP during the intra- and postoperative periods, such as alveolar recruitment maneuvers (ARMs), individualizing PEEP settings (through a decremental PEEP trial), FiO2 0.8, and ventilatory support in the immediate postoperative period, have physiological benefits, such as improvements in oxygenation, ventilation and respiratory mechanics as well as and a reduction in PPCs [17,18,27-30]. However, these strategies are not commonly used together in clinical practice [30,31]. We hypothesized that, compared to a standard low-VT lung-protective ventilation strategy applied to all intermediate- to high-risk surgical patients, individualized ventilatory management consisting of a strategy for minimizing lung collapse and overdistension that combines the use of low VT, ARMs, an individualized PEEP trial, reevaluation of PEEP during the intraoperative period, and individualized ventilatory support in the postoperative period, will decrease postoperative pulmonary and systemic complications in patients with no previous lung injury.

Therefore, iPROVE aims to compare the efficacy of perioperative individualized ventilation and standard lung-protective ventilatory strategies to reduce the overall incidence of a composite of pulmonary and systemic complications.

Methods

Study design

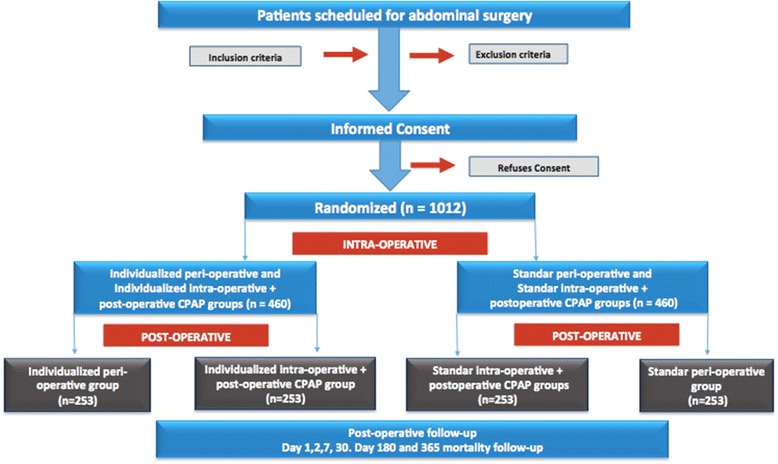

The Individualized Perioperative Open-lung Ventilatory Strategy (iPROVE) trial is a comparative, prospective, multicenter, randomized, and controlled four-arm trial that will include 1012 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of iPROVE. CPAP continuous positive airway pressure.

The trial has been designed in accordance with the fundamental principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki, the Convention of the European Council relating to human rights and biomedicine, and the Universal Declaration of UNESCO on the human genome and human rights, and with the requirements established by Spanish legislation in the field of biomedical research, the protection of personal data, and bioethics, which was classified by the Spanish Agency of Drugs and Medical Devices as a clinical randomized study without drugs on 8 April 2014 and registered on 5 June 2014 at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov with identification no. NCT02158923. Approval of the final protocol by the local committee at each participation center has been obtained prior to recruitment initiation (see Additional file 1).

Study population

The inclusion criteria of the study population consists of male and female patients ≥18 years old, with an intermediate or high risk of PPCs as defined by the ARISCAT score (based on the analysis of seven factors, in which a score between 26 and 44 points defines an intermediate risk and a score of more than 44 points defines a high risk [31]), with a body mass index (BMI) of <35 kg/m2, who are scheduled for major abdominal (laparotomy and laparoscopic) surgery with an expected operating time of more than 2 h (see Additional file 2). Exclusion criteria are age <18 years, pregnancy or breast-feeding, a body mass index of >35 kg/m2, moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; PaO2/FiO2 < 200 mmHg), diagnosis of heart failure defined as a cardiac index <2.5 ml/min/m2 or >2.5 when ≥5 μg/kg/min dobutamine is required, or suspicion of heart failure according to clinical signs (hypotension, oliguria, pulmonary edema) together with NT-proBNP >13 pg/ml, diagnosis or suspicion of intracranial hypertension (>15 mmHg), mechanical ventilation in the last 15 days (including CPAP), presence of pneumothorax or giant bullae on a chest radiograph or computed tomography (CT), patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) requiring oxygen or CPAP, and patients participating in another interventional study.

Method of randomization and bias minimization

Informed consent will be obtained from each participant before enrollment in the study. Patients who meet all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria will be consecutively included and randomized into one of the four study arms (Figure 1):

Individualized perioperative group;

Individualized intraoperative group + postoperative CPAP;

Standard intraoperative group + postoperative CPAP;

Standard perioperative group.

The patients will be randomized online via the website http://iprove.incliva.es using the Mersenne Twister algorithm with an allocation rate of 1:1:1:1.

Blinding: At least two investigators are required in each participating center, because the study characteristics do not allow the blinding of investigators in the operating and postoperative room, so data acquired in these sites will not be blinded. After 24 h, all data will be acquired by the second investigator who will be blinded to the randomization arm.

General procedures

All participating patients, regardless of the study arm into which they are randomized, will be monitored and managed following general standard of care practices aimed at maintaining optimal conditions. Both intraoperative and immediate-postoperative (3 h) anesthetic management (unrelated to ventilatory management) will be decided by the attending physician as they see fit, following the established protocols at each center. However, in order to ensure a high standard of anesthetic management, a number of common strategies have been established: halogenated agents will be given to maintain anesthesia, intra- and postoperative pain will be controlled with neuraxial anesthetics, hemodynamic management will be based on advance cardiac output monitoring, and fluids will be administered following goal-direct therapy principles. Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis will be administered, and pharmacological prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) will be adopted. Finally, when nasogastric tube insertion is required, it should be withdrawn prior to extubation when possible. All these data will be collected and analyzed.

Monitoring

Intraoperative monitoring will include an electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry, capnography, bladder or esophageal temperature, anesthetic depth analysis (bispectral analysis, BIS) and a neuromuscular blockade (with train of four, TOF), invasive blood pressure measurements, and advanced hemodynamic monitoring with minimally invasive monitoring (optional depending on the standard clinical practice and availability of equipment at each hospital). Ventilatory parameters will be monitored by the anesthesia machine: VT, PEEP, FiO2, peak airway pressure (Paw), plateau pressure (Pplat), and dynamic compliance of the respiratory system (Crs). Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) will be monitored during laparoscopic surgery. Postoperative monitoring will include at least an ECG, pulse oximetry, and invasive arterial pressure measurements.

General intraoperative ventilator management

Pre-oxygenation will be performed for 5 min at FiO2 0.8 with a tightly sealed face mask before induction. Patients will be ventilated in volume control mode (VCV) with squared flow, a VT of 8 ml/kg of the predicted body weight (PBW), and a Pplat of ≤25 cmH2O. If the Pplat reaches or exceeds 25 cmH2O, VT will be decreased in 1 ml/kg steps until the Pplat drops to ≤25 cmH2O. The respiratory rate (RR) will be set to maintain an end-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure (EtCO2) between 35–45 mmHg, with an inspiratory to expiratory ratio (I:E) of 1:2 and a inspiratory pause time of 20% of the inspiratory time. FiO2 will be set at 0.8 throughout the whole procedure. During the awakening period from general anesthesia (patients with spontaneous ventilation), a FiO2 of 0.8 will be applied at the same end-expiratory pressure used, using either PEEP or CPAP.

Extubation will not be allowed by applying a positive pressure above the previously set PEEP or CPAP or while suctioning through the tracheal device. If necessary, aspiration can be performed at least 10 min before extubation. After suction, the patient will be switched back to mechanical ventilation. If the patient is randomized into the individualized perioperative or individualized intraoperative + postoperative CPAP group, a new alveolar recruitment maneuver will be performed. Once extubation has been performed, the patient will be oxygenated with 0.5 FiO2 through a Venturi mask.

Specific intraoperative ventilatory management

The intraoperative ventilatory management comprises a two-arm management strategy (Figure 1).

Standard group

The patients will be ventilated as previously described in the General intraoperative ventilator management section.

Individualized group

In this group, an ARM is performed after intubation followed by a PEEP titration trial. Before the recruitment is performed the anesthesiologist must ensure that there is hemodynamic stability [mean arterial pressure (MAP) of more than 70 mmHg and/or a cardiac index of more than 2.5 ml/min/m2] for at least 5 min, a stroke volume variation (SVV) of less than 10%, and an adequate neuromuscular blockade (0 of 4 by TOF). The ARM is performed as described in the following section.

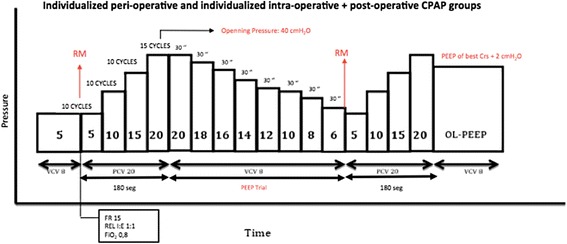

Alveolar recruitment maneuver (ARM)

The ventilator will be changed from VCV to pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) with a 20-cmH2O driving pressure and an RR of 15 breaths per minute (rpm), I:E of 1:1, 0.8 FiO2, and PEEP of 5 cmH2O. For the recruitment phase, the PEEP level will be increased in steps of 5 cmH2O every ten respiratory cycles, up to a PEEP of 20 cmH2O, to produce an airway opening pressure of 40 cmH2O and maintained for 15 respiratory cycles in the opening pressure [32] (total maneuver time: 180 s). If hemodynamic instability appears during the recruitment phase (a >50% decrease in the cardiac index or MAP), the maneuver will be interrupted and 5–15 mg ephedrine or 0.05-0.15 mg phenylephrine given; after hemodynamic stabilization, a new ARM will be performed. After lung recruitment is accomplished, the optimal PEEP is titrated through a decremental PEEP trial, as described in the following section [8] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Alveolar recruitment maneuver and PEEP titration trial protocol. RM recruitment maneuver, Crs respiratory system compliance, PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure, CPAP continuous positive end-expiratory pressure, VCV volume-controlled ventilation, PCV pressure-controlled ventilation, RR respiratory rate, I:E inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio.

Titration of the optimal individual positive end-expiratory pressure: Decremental PEEP trial

At the end of the last step of the PCV recruitment phase when the PEEP is 20 cmH2O, the mode will be switched to VCV with a VT of 8 ml/kg, RR of 15 rpm, and I:E of 1:2, 0.8 FiO2. After this, PEEP is decreased 2 cmH2O steps every 30 s until the highest Crs observed on the ventilator’s monitor (until Crs starts decreasing or does not increase). Once the best Crs is known, a new recruitment maneuver is performed and the PEEP for the best Crs + 2 cmH2O is adjusted. In the case of accidental airway depressurization, a new ARM is performed while an identical PEEP is set (Figure 2).

The need for new recruitment maneuvers and a PEEP trial is evaluated every 40 min by measuring the CRS and peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2). If there is a drop of more than 10% of the Crs, FiO2 will be transitorily decreased to 0.21-0.25 for at least 4 min, and if SpO2 drops to ≤96% at this FiO2, a new recruitment and PEEP trial are performed.

Intraoperative rescue maneuvers

In the case of arterial hypoxemia (SpO2 of ≤95% with FiO2 0.8), after excluding endobronchial tube displacement, bronchospasm, pneumothorax, or a hemodynamic cause, a protocol for rescue therapy has been devised for each specific group.

Individualized group

A new recruitment maneuver and PEEP trial are performed. If SpO2 is less than 95%, FiO2 is increased in 0.1 steps.

Standard group

The 0.1 FiO2 is increased until SpO2 is more than 95%. If arterial hypoxemia persists with 1.0 FiO2, the PEEP is increased in steps of 2 cmH2O (until a maximum of 12 cmH2O).

General postoperative management in the postoperative care unit

General postoperative management in the postoperative care unit (PACU) not related to ventilator management will be decided by the attending physician following the established protocols at each center. Patients will be oxygenated with FiO2 0.5 through a Venturi mask for the first 15 min. The arterial oxygenation will be evaluated 15 to 30 min later when patients are awake and collaborative [Glasgow coma score (GCS) higher than 13] without any residual anesthetic effect (Richmond scale −1 to +1) and under pain control [verbal analog pain scale (echelle verbal analogique; EVA) score <4] by decreasing the FiO2 to 0.21 for at least 5 min (air test). The air test is intended to identify possible decreases in SpO2 related to postoperative atelectasis that may have been masked by the use of 0.5 FiO2. The air test is not performed if the patient already has an SpO2 below 96% with FiO2 0.5. Air tests are repeated at 60, 120, and 180 min after PACU admission in all study patients. When the patient arrives in the PACU or ICU with invasive mechanical ventilation, the above-mentioned management will be applied after extubation.

Specific postoperative ventilatory management

Postoperative ventilatory management consists of two types of management for each of the two intraoperative arms (Figure 1).

Individualized perioperative group

Supplemental oxygen at FiO2 0.5 will be delivered through a Venturi mask. If SpO2 falls below 96% during the room-air test (FiO2 0.21 for 5 min), a CPAP of 5 cmH2O (or 10 cmH2O if the BMI exceeds 30) with FiO2 0.5 will be initiated. Reevaluation of arterial oxygenation will be performed every hour for the first 3 postoperative hours. If patients require CPAP at any time during their PACU stay, it will be maintained for 3 h, independently of their oxygenation levels.

Individualized intraoperative + postoperative CPAP group

A CPAP of 5 cmH2O (or 10 cmH2O if the BMI exceeds 30) with a FiO2 0.5 will be applied to all patients in this group.

Standard + postoperative CPAP group

A CPAP of 5 cmH2O (or 10 cmH2O if the BMI exceeds 30) with a FiO2 0.5 will be applied to all patients in this group.

Standard group

Supplemental oxygen at 0.5 FiO2 will be delivered through a Venturi mask.

If any patient in any group experiences PONV or does not tolerate the CPAP device, they will be changed to standard therapy.

Postoperative rescue maneuver

Rescue therapies are initiated if the SpO2 decreases to 92% or less during the air test or if SpO2 is 95% or less while on 0.5 FiO2, with or without pressurization according to the patient’s randomized group. Evaluation of a positive or negative response to the rescue maneuver is performed in a maximum period of 30 min.

Individualized perioperative group:

For patients with a 0.5 FiO2 Venturi mask, the rescue maneuver is started with 5 cmH2O CPAP (or 10 cmH2O if the BMI exceeds 30). If the patient is already on 5 cmH2O CPAP, it will be increased to 10 cmH2O.

In patients with a BMI exceeding 30 or with persistent hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia [blood partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) >50 mmHg with a pH <7.30], tachypnea (RR >25 rpm), or increased activity of accessory respiratory muscles are present, inspiratory support with noninvasive ventilation (NIV) will be started.

Individualized intraoperative + postoperative CPAP and Standard + postoperative CPAP group:

CPAP will be increased to 10 cmH2O in all cases.

In patients with a BMI of more than 30 or persistent hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 50 mmHg with a pH <7.30), tachypnea (RR >5 rpm), or increased activity of accessory respiratory muscles are present, inspiratory support with NIV will be started.

Standard group:

FiO2 will be increased to 0.8 through a controlled FiO2 mask with a reservoir bag.

If there is persistent hypoxemia, CPAP of 5 cmH2O (or 10 cmH2O if the BMI exceeds 30) will be used.

If hypoxemia persists, CPAP will be increased to 10 cmH2O.

If persistent hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 50 mmHg with a pH <7.30), tachypnea (RR exceeding 25 rpm), or increased activity of accessory respiratory muscles are present, inspiratory support with NIV will be started.

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV)

The ventilator (specific for NIV or with software for NIV) and interface for NIV will be chosen by the attending physician and based on hospital availability. CPAP, i.e., expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP), and FiO2 will be set according to the patient’s randomized group. Positive pressure will start with an inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) of 5 cmH2O higher than the EPAP and will be increased in steps of 5 cmH2O up to 15 cmH2O. The EPAP will be increased to a maximum of 10 cmH2O (15 cmH2O if the BMI exceeds 30).

Invasive ventilation

Direct tracheal intubation (without NIV trial) will be indicated if the patients also meet at least one of the following criteria:

Hemodynamic instability [a systolic blood pressure (SBP) <80 mmHg or <40% of the basal or vasoactive drug requirements for more than 2 h is required to maintain the SBP above 80 mmHg].

Ventricular arrhythmias with hemodynamic instability or ECG signs of myocardial ischemia.

GCS of less than 9.

Sedation requirement due to agitation.

Tracheal intubation after 1 h of NIV will be indicated in patients meeting at least one of the following criteria:

Severe hypoxemia (SpO2 < 92% with a FiO2 as prescribed according to the randomized group).

Respiratory acidosis (pH <7.30 with a PaCO2 > 50 mmHg).

Signs of distress with increased use of accessory respiratory muscles or paradoxical thoracic-abdominal respiratory movements.

Study variables

The primary outcome of the iPROVE trial is a composite of pulmonary and systemic complications experienced by the study population in the first 7 days after surgery and can be divided into respiratory complications and systemic complications as discussed below.

Respiratory complications:

Atelectasis: defined by a combination of SpO2 ≤ 96% during the air test and chest X-ray images suggesting lung opacities with a shift in the mediastinum, hilum, or hemidiaphragm toward the affected area and compensatory overinflation in the adjacent non-atelectic lung.

Hypoxemia: defined as SpO2 of 92% or less with 0.21 FiO2 or SpO2 of 95% or less with 0.5 FiO2.

ARDS: according to the Berlin definition [33].

Pneumonia: the presence of a new pulmonary infiltrate and/or progression of previous pulmonary infiltrates on a chest radiograph plus at least two of the following criteria: (a) leukocytosis with >12,000 WBC/mm3 or leukopenia with <4000 WBC/mm3, (b) fever >38.5°C or hypothermia <36°C, and (c) increased secretions with purulent sputum and a positive bronchial aspirate.

Pleural effusion: chest x-ray with the presence of costophrenic angle blunting, displacement of adjacent anatomical structures, and blunting of the hemidiaphragmatic silhouette in the supine position.

Bronchospasm: presence of expiratory wheezing treated with bronchodilators.

Pneumothorax: air in the pleural space and the mediastinum is shifted to the opposite side (a thorax radiography will be performed in suspected cases of auscultation hoarseness).

Aspiration pneumonitis: respiratory failure after the inhalation of regurgitated contents.

Requirements for rescue maneuvers: increased FiO2, increased requirement for CPAP, or the need for noninvasive or invasive ventilation.

Early extubation failure or requirement of reintubation.

Systemic complications:

Heart failure: cardiac index <2.5 ml/min/m2 or >2.5 when ≥5 μg/kg/min dobutamine is required. Clinical signs (hypotension, oliguria, pulmonary edema) together with NT-proBNP >13 pg/ml or echocardiographic diagnosis [34].

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): axillary temperature >38.5°C or <35.5°C, or central temperature of 38°C and 36°C, respectively. Heart rate (HR) >90 bpm (in the presence of atrial arrhythmia, the ventricular rate measurement will be used). If medication that could affect the HR is administered, the patient must meet the following three criteria: (a) RR >20 rpm, (b) a PaCO2 of <32 mmHg or use of mechanical ventilation, (c) leukocytosis of ≥12 × 109/l, or leukopenia of <4 × 109/l.

Sepsis: infectious focus identified plus SIRS criteria.

Severe sepsis: sepsis plus at least one organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension.

Septic shock: Severe sepsis with hypotension and hypoperfusion that is unresponsive to fluids.

Renal failure, following the acute kidney injury scale [35].

Anastomosis dehiscence: suture line failure with leakage of the intraluminal contents that may cause peritonitis, fistula from the wound or drain, or appearing as an abdominal fluid collection (diagnosed with imaging) that causes fever, septicemia, and shock.

Abdominal abscess diagnosed with imaging techniques (CT).

Surgical wound infection: following the CDC criteria [36].

Surgical reintervention required.

The secondary outcomes are the composite of postoperative pulmonary complications at 7 days and over the first 30 post-surgical days. Other secondary outcomes are:

Increased ICU length of stay (LOS).

Increased hospital LOS.

ICU readmission in the first 30 days after surgery.

Hospital readmission in the first 30 days after surgery.

Mortality within 30, 180, or 365 days.

The presence of plasma inflammatory markers: increased expression of interleukin 8 (IL-8), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and monocyte chemo-attractant protein (MCP-1). Plasma samples will be taken preoperatively and 48 h post-surgery.

The primary and secondary data outcomes will be taken 15 min and 3 h after PACU/ICU admission and at 1, 2, 7, and 30 days after surgery, with a 180- and 365-day follow-up for mortality. Plasma samples will be taken preoperatively and at 2 days after surgery. If the patient is not extubated in the operating room, the first four data time points will be taken from the time of extubation.

Other follow-up variables

Baseline variables will be recorded preoperatively and are age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, ARISCAT [26] risk score, type of intervention, and medical history.

Intraoperative parameters recorded at three different time points (post-induction, 60 min after induction, and pre-extubation) will be: arterial blood gases, SpO2, FiO2, respiratory variables [VT, PEEP, Paw, Pplat, Crs, respiratory system resistance (Raw), hemodynamics (cardiac index, PAM, and stroke volume variation (SVV) and/or pulse pressure variation (PPV)], diuresis, and temperature. Other relevant data that include the types of anesthetic drugs used, type and volume of fluids, blood loss and transfusion requirements, need of vasoactive drugs, diuresis, nasogastric tube insertion, duration of surgery, mechanical ventilation time, number of recruitment maneuvers performed, and the need for rescue therapy will also be recorded.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was estimated from the literature, assuming a risk of 25% for developing postoperative pulmonary or non-pulmonary complications [17], a relative reduction of 50% in the incidence of these complications with individualized alternative treatment in the groups, and taking into account the statistical power for making matched comparisons between the four groups in the study [37]; using a significance level of 5% and a power of 80% results in a total requirement of 920 patients (230 in each ventilatory management group). This figure was enlarged to 1012 (10%) to compensate for possible dropouts. The recruitment among centers will be competitive.

First, the patient baseline variables will be described and the homogeneity of these groups evaluated using appropriate statistical tests for the type of variable being analyzed (mean difference of proportions, chi-square, ANOVA, with a corresponding confidence interval of 95%). Then bivariate associations between patient characteristics, the primary endpoint, and the secondary outcomes will be performed by calculating their respective odds ratios or, in the case of a quantitative outcome, by an ANOVA test.

Following this, the association between the intervention groups and the main and secondary outcomes will be analyzed, calculating the corresponding odds ratio, or ANOVA in the case of quantitative outcomes. In all cases, respective means or proportions are estimated with their respective 95% confidence intervals. The primary outcome, pulmonary complications outcome, non-pulmonary complications, and mortality measurement analyses will be repeated using multivariate logistic regression models and adjusted to any patient characteristics that are shown to be clinically relevant by the previous bivariate analyses. Similarly, a multilevel analysis will be performed, incorporating different hospitals as random effects in order to assess whether the recruitment center influenced the results.

The monitoring plan is based on the modified Haybittle-Peto boundaries for stopping trials after interim analyses in the second half of the inclusion period [38,39]. Analysis of the main endpoint will be presented to the Data and Safety management board under a blinded code for allocation group. The first interim analysis will be conducted when outcome data of 460 trial participants have been obtained and/or the main endpoints for 150 participants have been documented. If this first interim analysis is significant (P <0.001) for benefit or harm from the intervention, a second interim analysis will be carried out when outcome data for 600 trial participants have been obtained. If this second interim analysis is also statistically significant (P <0.001) for benefit or harm, the Data and Safety management board will advise the Steering Committee to stop the trial.

Trial organization

The steering committee is constituted by the study principal investigators who contributed to its design and approved the final protocol. The executive committee comprises the main investigators of each participating center and is responsible for administrative, trial, and data management. The Data and Safety management board is composed of independent experts in mechanical ventilation and multicenter trials, and it recommends the continuance or discontinuation of the study based on the evidence collected at interim analysis intervals. The trial management team comprises a chief investigator, a project manager, a statistician, and an investigator expert in informatics. The responsibilities of this team are:

Planning and conducting the study: designing the protocol, case report, and electronic case report (e-CRF) forms, designing the investigator manual, and managing and controlling the data quality.

Research center support: assisting the centers with the administrative submission, monitoring recruitment rates and taking action to increase recruitment if necessary, monitoring follow-ups, auditing, and sending study materials to the research centers.

Producing a monthly study newsletter and developing supporting material for the study.

Statistical analysis and research reporting: complete statistical analysis and helping in writing the final manuscript.

Discussion

Postoperative pulmonary and systemic complications are a common problem in patients with an intermediate or high risk of PPCs, and there is clear evidence showing that protective mechanical ventilation can attenuate these complications by limiting lung injury and the systemic inflammatory response [17,20].

Atelectasis appears in almost all patients during general anesthesia, favoring the two mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) [40-42]: alveolar cyclic recruitment/derecruitment and overdistension because the aerated part of the lung receives most of the VT. These mechanisms produce alveolar damage and trigger the local and systemic inflammatory responses, favoring pulmonary and systemic lung complications, even in short-term mechanical ventilation in previously healthy lungs [12,43].

Lung-protective mechanical ventilation with a low VT minimizes overdistension and reduces lung injury not only in ARDS patients or patients without lung injury receiving long-term mechanical ventilation, but also during intraoperative short-term mechanical ventilation. This has been recently confirmed in a randomized controlled trial [17] and in previous meta-analyses [18,19]. The use of a low VT favors atelectasis and therefore makes PEEP the other key point in the lung-protective ventilatory strategy, which aims to avoid cyclic recruitment/derecruitment. However, the ideal PEEP level is not yet known because of the high heterogeneity in the methods for setting the PEEP settings and the different PEEP levels used in previous trials.

Recently, two large randomized controlled trials tried to show the benefits of the open lung concept, including recruitment maneuvers and higher PEEP levels than those normally used in clinical practice. The PROtective Ventilation using High versus Low positive end-expiratory pressure (PROVHILO) study showed no differences between high PEEP (12 cmH2O) levels combined with recruitment maneuvers compared to a low PEEP (less than 2 cmH2O) levels [20]. These results may be explained by the use of an inadequate opening pressure during the recruitment maneuver (30–35 cmH2O) during only three respiratory cycles or may be related to the use of inadequately high PEEP levels that may well be as harmful in terms of lung injury as low PEEP levels. The Intraoperative Protective Ventilation in Abdominal Surgery (IMPROVE) study showed that the strategy of a VT of 6–8 ml/kg IBW with repetitive recruitment maneuvers combined with a standardized PEEP level (6–8 cmH2O) was beneficial, but only compared to the nonprotective ventilation strategy using high VT (10–12 ml/kg IBW) with no PEEP [17].

Although the IMPROVE strategy resulted in a positive effect of the open lung concept, we believe that it could be improved by limiting the unnecessary number of recruitment maneuvers during the intraoperative period because it is known that ARMs themselves can trigger an inflammatory response. Thus, this strategy can be further improved by individualizing the PEEP level titration; this approach maintains the benefits of the maneuver and makes it more time-effective, therefore decreasing the need for repeated recruitment maneuvers [8]. Another important intraoperative strategy for optimal care proposed in this study is the use of 80% supplemental oxygen, which has been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of SSIs without increasing postoperative pulmonary complications [24]. Finally, atelectasis formation is favored in the immediate postoperative period by many factors. Several clinical studies show that prophylactic pressurization, or pressurization at the first sign of hypoxemia, reduces postoperative pulmonary complications [30].

Despite these interesting results, there are no clinical trials that apply these strategies with an individualized approach in both the intraoperative and postoperative period settings, i.e., by integrating intraoperative and immediate postoperative strategies, but aiming all of them toward protecting the lung from injury and thus reducing pulmonary and non-pulmonary postoperative complications.

In this trial, the effectiveness of individualized implementation and global approaches to lung-protective ventilation, to keep lung collapse and overdistension to a minimum, will be evaluated. The strategy includes all the maneuvers that have previously been shown to have a beneficial effect:

Low VT

ARMs

Individualized PEEP setting with a decremental PEEP trial

Reevaluation of PEEP during the intraoperative period

High intraoperative FiO2

Individualized ventilatory support in the postoperative period.

If the trial demonstrates that the individualized perioperative global approach decreases postoperative complications, these findings will represent a big improvement in the management of moderate- and high-risk surgical patients.

Trial status

The iPROVE screening for patients begins in January 2015. Local ethics approval at each participation center is required.

Acknowledgments

Funding source

This trial is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant PI14/00829, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund), and the support of the Grants Programme of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. CR is funded by grant RD12/0001/0005 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund).

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ARM

Alveolar recruitment maneuvers

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- BIS

Bispectral analysis

- BMI

Body mass index

- Bpm

Breaths per minute

- C

Confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

- Crs

Dynamic compliance of the respiratory system

- CT

Computed tomography

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- EPAP

Expiratory positive airway pressure

- EtCO2

End-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure

- EVA

Visual analog pain scale (echelle visuelle analogique EVA)

- FiO2

Inspiratory oxygen fraction

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Score

- HR

Heart rate

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- I:E

Inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio

- IL-8

Interleukin 8

- IPAP

Inspiratory positive airway pressure

- IPROVE

Individualized perioperative open lung ventilatory strategy

- LOS

Length of stay

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemo-attractant protein

- MV

Mechanical ventilation

- NIV

Noninvasive ventilation

- PaCO2

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PACU

Postoperative care unit

- Paw

Peak airway pressure

- PBW

Predicted body weight

- PCV

Pressure control ventilation

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- PPCs

Postoperative pulmonary complications

- Pplat

Plateau pressure

- PONV

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- PPV

Pulse pressure variation

- Raw

Respiratory system resistance

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RR

Respiratory rate

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SIRS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SpO2

Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation

- SSI

Surgical site infection

- SVV

Stroke volume variation

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TOF

Train of four

- VCV

Volume control ventilation

- VILI

Ventilator-induced lung injury

- VT

Tidal volume

Appendix 1

The iPROVE Investigators consist of:

Steering committee: Carlos Ferrando, Javier Belda, Marina Soro, Jaume Canet, Carmen Unzueta, Fernando Suárez, Julián Librero, Alicia Llombart.

Executive committee: Carlos Ferrando, Jaume Canet, Mª Carmen Unzueta, Lucas Rovira, Fernando Ramasco, Manuel Granell, César Aldecoa, Oscar Diaz, Jaume Balust, Ignacio Garutti, Roque Company, Teresa Alonso, Rafael Gonzalez, Mª Eugenia Durán, Lucia Gallego, Santiago García del Valle, Javier Redondo, Pedro Diaz, David Pestaña, Aurelio Rodríguez, Marisol Hernandez, Javier García, Elena Espinosa, Pedro Charco, Manuel de la Matta, Maite Ibáñez, Francisco Barrios.

Data and Safety management board: Jesus Villar, Joao Borges, Samir Jaber.

Trial management committee: Carlos Ferrando, Alicia Llombart, Marina Soro, Carlos Delgado, Salvador Peiró.

Appendix 2

iPROVE investigators:

Esther Romero, Carolina Romero, Amanda Miñana, Tania Moreno, Antonio Katime, Estefanía Gracia, Ana Izquierdo, Tania Socorro, Concepción Rubio, Paola Valls, Angels Lozano, Alejandro Duca, Raul Incertis, Isabel Fuentes, Ana Jurado, Juan Carrizo, Jose Navarro, Abigail Villena, Ferran Serralta, Jose A Carbonell, Jaume Puig, Ernesto Pastor, Blanca Arocas, Mª Luisa García, Andrea Gutierrez, Gerardo Aguilar, Ana Mugarra, Jose M. Alonso, Maria J. Parra, Mario de Fez, Esperanza Mata, Jesus Nieves, Carlos Alvarez, Raquel Tolos, Mar Sendra, Andrea Brunelli, Virginia Cegarra, Mercedes García, Gonzalo Azparren, Patricia Piñeiro, AnaM Lajara, Jose M Pérez, Jose A de Andrés, Maria J Hernández, Lorena Gómez, Teresa Alonso, Sara Rodiño, Marta López, AnaM Pérez, Jose M Marcos, Fernando Díez, Mª Piedad Martínez, Mª del Mar Hernández, José Fernandez-Pacheco, Maria J Rivera, M Galiana, Roque Company, Ana Colás, Irene Molinós, Ana Asensio, Margarita Vergas, Clara García, Jesus Rico, Pablo García, Jose I. García, Viviana Varón, Eva Romero, Guido Mazzinari, Esperanza Herrera, Eva Rosado, Patricia Ramos, Nazario Ojeda, Oto Padrón, Lucia Valencia, Sergio Cabrera, Rayco Rodríguez, Antonio Romero, Ana González, Jessica García, Nilda Martinez de Castro, Cristina Medrano, Nuria Mané, Graciela Martínez, Roger Pujol, Amalia Alcon, Vicente Torres, Javier Román Marta García, Alejandro Dominguez, Inmaculada Benítez, Domingo González, Daniel López-Herrera, M. Sol Hernández, Clara Morales, David Soriano, David Domínguez, Samuel Hernández, Maria Vila, Maria J Alberola, Sandra Verdeguer, Maite Ibáñez, Elena Lozano, Jose Valdivia, Vicente Gilabert, Francisco Barrios, Mercedes Ayuso, Ricardo Moreno.

Additional files

Ethics committees that approved the final protocol.

Surgical procedures included in the study protocol.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CF, FJB, JC, MS, FS, ALl, MªCU, JL, SP, CD, IL, and GT conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. LR, FR, MG, CA, OD, JB, IG, MM, AP, RG, MªED, LG, SGdV, JA, FJR, PD, DP, AR, JMG, JG, EE, PC, JN, and CR helped to design the final manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Carlos Ferrando, Email: cafeoranestesia@gmail.com.

Marina Soro, Email: soromarina@gmail.com.

Jaume Canet, Email: jcanet54@gmail.es.

Ma Carmen Unzueta, Email: mcunzueta@gmail.com.

Fernando Suárez, Email: fsuarez.sipmann@surgsci.uu.se.

Julián Librero, Email: librero_jul@gva.es.

Salvador Peiró, Email: peiro_bor@gva.es.

Alicia Llombart, Email: allombart@incliva.es.

Carlos Delgado, Email: cardelna@gmail.com.

Irene León, Email: irene.leon.carsi@gmail.com.

Lucas Rovira, Email: lucasrovira@gmail.com.

Fernando Ramasco, Email: gorria66@gmail.com.

Manuel Granell, Email: mgranellg@gmail.com.

César Aldecoa, Email: cesar.aldecoa@gmail.com.

Oscar Diaz, Email: oscardiazcambronero@gmail.com.

Jaume Balust, Email: jbalust@clinic.ub.es.

Ignacio Garutti, Email: ngaruttimartinez@yahoo.es.

Manuel de la Matta, Email: mdlmatta@hotmail.com.

Alberto Pensado, Email: Teresa.Alonso.Ferreira@sergas.es.

Rafael Gonzalez, Email: rafarealeon@gmail.com.

Mª Eugenia Durán, Email: geniaduran@gmail.com.

Lucia Gallego, Email: lgallegoligorit@gmail.com.

Santiago García del Valle, Email: sgarcia@anestesiar.org.

Francisco J Redondo, Email: ardredondo@hotmail.com.

Pedro Diaz, Email: d_spedro@hotmail.com.

David Pestaña, Email: dpestanalag@hotmail.com.

Aurelio Rodríguez, Email: arodperp@gobiernodecanarias.org.

Javier Aguirre, Email: javier.aguirrearas@osakidetza.net.

Jose M García, Email: JMGG1982BOLLU@hotmail.com.

Javier García, Email: ventilacionanestesia@gmail.com.

Elena Espinosa, Email: mespdom@gmail.com.

Pedro Charco, Email: pcharco@gmail.com.

Jose Navarro, Email: jnavarro.martinez@gmail.com.

Clara Rodríguez, Email: rodriguez_claber@gva.es.

Gerardo Tusman, Email: gtusman@hotmail.com.

Francisco Javier Belda, Email: fco.javier.belda@uv.es.

References

- 1.Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB, Lipsitz SR, Berry WR, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372:139–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ. Participants in the VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242:326–41. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner DO. Preventing postoperative pulmonary complications: the role of the anesthesiologist. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1467–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks-Brunn JA. Postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia. Heart Lung. 1995;24:94–115. doi: 10.1016/S0147-9563(05)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slutsky AS. Lung injury caused by mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1999;116:9S–15. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.9S-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao T, Bo L, Chen F, Xie Q, Zou Y, Hu B, et al. Effect of protective ventilation on postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing general anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:347–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrando C, Ferrando C, Mugarra A, Gutierrez A, Carbonell JA, García M, et al. Setting individualized positive End-expiratory pressure level with a PEEP decrement trial after a recruitment maneuver improves oxygenation and lung mechanics during One-lung ventilation. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:657–65. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whalen FX, Gajic O, Thompson GB, Kendrick ML, Que FL, Williams BA, et al. The effects of the alveolar recruitment maneuver and positive end-expiratory pressure on arterial oxygenation during laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:98–305. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000183655.57275.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, Roelofs JJ, Juffermans NP, Schultz MJ. Mechanical ventilation using noninjurious ventilation settings causes lung injury in the absence of preexisting lung injury in healthy mice. Crit Care. 2009;13:R1. doi: 10.1186/cc7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imai Y, Parodo J, Kajikawa O, de Perrot M, Fischer S, Edwards V, et al. Injurious mechanical ventilation and end-organ epithelial cell apoptosis and organ dysfunction in an experimental model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2003;289:2104–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michelet P, D’Journo XB, Roch A, Doddoli C, Marin V, Papazian L, et al. Protective ventilation influences systemic inflammation after esophagectomy: a randomized controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:911–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villar J, Kacmarek RM, Pérez-Méndez L, Aguirre-Jaime A. A high positive end- expiratory pressure, low tidal volume ventilatory strategy improves outcome in persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1311–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215598.84885.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Needham D, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Dinglas VD, Sevransky JE, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, et al. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:2124–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Determann RM, Royakkers A, Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, Paulus F, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with conventional tidal volumes for patients without acute lung injury: a preventive randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R1. doi: 10.1186/cc8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Futier E, Constantin JM, Paugam-Burtz C, Pascal J, Eurin M, Neuschwander A, et al. A trial of intraoperative Low-tidal-volume ventilation in abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:428–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serpa Neto A, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, Pereira VG, Espósito DC, Pasqualucci Mde O, et al. Association between use of lung- protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308:1651–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmes SN, Serpa Neto A, Schultz MJ. Intraoperative ventilatory strategies to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications: a meta-analysis. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2013;26:126–33. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32835e1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The PROVE. Network investigators High versus low positive end-expiratory pressure during general anesthesia for open abdominal surgery (PROVHILO trial): a multicenter randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:495–503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumb AB, Walton LJ. Perioperative oxygen toxicity. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;30:591–605. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrando C, Soro M, Belda J. Protective strategies during cardiopulmanory bypass: ventilation, anesthestics and oxygen. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.García-de-la-Asunción J, Barber G, Rus D. Hyperoxia during colon surgery is associated with a reduction of xanthine oxidase activity and oxidative stress in colonic mucosa. Redox Rep. 2011;16:121–8. doi: 10.1179/174329211X13049558293632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hovaguimian F, Lysakowski C, Elia N, Tramèr MR. Effect of intraoperative high inspired oxigen fraction on surgical site infection, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and pulmonary function: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:303–16. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829aaff4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belda FJ, Catalá-López F, Greif R, Canet J. Benefits and risks of intraoperative high inspired oxygen therapy: firm conclusions are still far off. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1051–2. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canet J, Belda FJ. Perioperative hyperoxia: the debate is only getting started. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1271–3. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31821bdbb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Carlesso E. How to ventilate patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:69–76. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200502000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maish S, Reissmann H, Fuellekrug B, Weismann D, Rutkowski T, Tusman G, et al. Compliance and dead space fraction indicate an optimal level of positive End-expiratory pressure after recruitment in anesthetized patients. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:175–81. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000287684.74505.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glossop A, Shephard N, Bryden DC, Mills GH. Non-invasive ventilation for weaning, avoiding reintubation after extubation and in the postoperative period: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:305–14. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ireland CJ, Chapman TM, Mathew SF, Herbison GP, Zacharias M. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during the postoperative period for prevention of postoperative morbidity and mortality following major abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD008930. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008930.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, Paluzie G, Vallès J, Castillo J, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1338–50. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fc6e0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tusman G, Belda FJ. Treatment of anesthesia-induced lung collapse with lung recruitment maneuvers. CACC. 2010;21:244–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Authors/Task Force Members, Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray J, Ponikowski P, et al. ESC. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the european society of cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the heart failure association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the european society of intensive care medicine (ESICM). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388–442. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network: acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:606–8. doi: 10.2307/30148464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chow S. Sample Size calculations in clinical research. Chapman & Hall/CRC Biostatistics Series; 2008

- 38.Haybittle JL. Repeated assessment of results in clinical trials of cancer treatment. Br J Radiol. 1971;44:793–7. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-44-526-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bendixen HH, Hedley-Whyte J, Laver MB. Impaired oxygenation in surgical patients during general anesthesia with controlled ventilation: a concept of atelectasis. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:991–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196311072691901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnusson L, Spahn DR. New concepts of atelectasis during general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:61e72. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duggan M, Kavanagh BP. Pulmonary atelectasis: a pathogenic perioperative entity. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:838–54. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinberg JM, Schiller HJ, Halter JM, Gatto LA, Lee HM, Pavone LA, et al. Alveolar instability causes early ventilator-induced lung injury independent of neutrophils. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:57e63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-544OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]