Abstract

Shifting the field of developmental toxicology towards evaluation of pathway perturbation requires a quantitative definition of normal developmental dynamics. This project examined a publicly available dataset to quantify pathway dynamics during testicular development and spermatogenesis and anchor toxicant-perturbed pathways within the context of normal development. Genes significantly changed throughout testis development in mice were clustered by their direction of change using K-means clustering. Gene Ontology terms enriched among each cluster were identified using MAPPfinder. Temporal pathway dynamics of enriched terms were quantified based on average expression intensity for all genes associated with a given term. This analysis captured processes that drive development, including the peak in steroidogenesis known to occur around gestational day 16.5 and the increase in meiosis and spermatogenesis-related pathways during the first wave of spermatogenesis. Our analysis quantifies dynamics of pathways vulnerable to toxicants and provides a framework for quantifying perturbation of these pathways.

Keywords: testicular development, spermatogenesis, quantitative pathway analysis

Introduction

Increasing rates of reproductive disorders that have origins in early reproductive development demonstrate the need for methods to characterize and quantify perturbations of developmental processes in gonadal development and spermatogenesis. For example, there is mounting evidence for a consistent decline in semen quality in recent decades, accompanied by an increasing prevalence of male reproductive disorders, including hypospadias, undescended testes, and testicular cancer [1–6]. All of these adverse reproductive health outcomes are manifestations of testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), a set of conditions believed to have common origins during early gonadal development [7]. Early testicular development and spermatogenesis are very sensitive processes that depend on a series of precisely timed steps regulated by hormonal cues and germ cell microenvironments [8, 9]. These processes in male reproductive development are therefore particularly vulnerable to perturbation by genetic and environmental factors [10, 11]. Indeed, the recent increase in TDS related conditions has been hypothesized to be a result of environmental factors that can influence early male reproductive development, such as exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals [7].

Exploration of the complex interaction of environmental and genetic factors underlying reproductive disorders requires a systems-based framework for characterizing normal and perturbed pathway dynamics during critical windows of male reproductive development. The field of toxicology is increasingly shifting towards characterization of pathway perturbation as a sensitive indicator of toxicity [12]. A quantitative framework for measuring shifts from normal pathway dynamics would facilitate quantification of pathway perturbation by toxicants. Furthermore, incorporation of in vitro models into chemical screening, underscores the need to anchor pathway dynamics captured in these in vitro models to pathway dynamics driving in vivo development. The first step in being able to place pathway perturbation measured in vivo and in vitro within the context of normal development is to define normal pathway dynamics in vivo in an easily translatable, quantitative framework.

Fortunately, much of the data needed to provide this baseline characterization of normal developmental dynamics is available in publicly available datasets. Microarray-based high-throughput gene expression analysis has proven to be an effective method for studying the changes in gene expression associated with the growth and development of mammalian tissues [13, 14]. Many of the genetic drivers of male reproductive development have been characterized through mouse knockout models [15, 16] and global gene expression analysis [17–21]. The Griswold lab at Washington State University has employed microarray-based gene expression analysis to characterize dynamic changes in global gene expression patterns over the course of several particularly sensitive processes of male reproductive development in mice [17, 18]. The group identified genes with changing expression patterns throughout gonadal differentiation and development and the first wave of spermatogenesis [17, 18]. The gene expression profiles observed by Small et al reiterated the known functional activities of each cell type, and suggested the involvement of novel genes in the maturation of the testis and differentiation of germ cells. Their temporal microarray study provides a valuable resource for evaluating biological factors that influence testis maturation and spermatogenesis. However, as with all microarray data, the functional interpretation of such a vast set of genomic data presents a major challenge. In order to elucidate the biological consequences of these expression changes in single genes, gene expression data must be integrated with quantitative information on functional changes in whole gene networks and developmental signaling pathways over time.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis is a powerful tool for translating a vast amount of genomic data into a description of functional changes in gene networks and signaling pathways. The GO approach has been successfully combined with pathway analysis to generate an unbiased determination of the statistical significance of changes observed in pathways of interest [22–25]. For example, previous GO analysis of testicular gene expression has successfully identified pathways that are significantly changed throughout murine spermatogenesis [26]. However, standard GO analysis results in a list of enriched pathways with no quantitative description of how these pathways are changed. In addition these approaches did not retain quantitative information on the expression of individual genes and are limited to the evaluation of only two experimental dimensions.

In order to address the need to quantify changes in pathway dynamics through time or in response to an environmental exposure, our lab developed the GO-Quant approach [27]. GO-Quant incorporates gene expression data with Gene Ontology analysis in MAPPfinder [22] to calculate the average intensity of expression of all significantly altered genes associated with a given GO term. This allows the quantitative evaluation of the dynamics of entire gene pathways along a third dimension, such as developmental stage or toxicant dose. We first applied this quantitative pathway-based approach in a published dose- and time-dependent genomic dataset [28] and found that our systematic approach quantitatively described the degree to which functional gene systems changed across dose or time course [27, 29]. We have subsequently used our quantitative pathway analysis for a genome-wide assessment of phthalate toxicity in an in vitro rat testis co-culture model [30] and for an assessment of time- and dose-dependent methylmercury toxicity in developing mouse embryos undergoing neurulation [31].

In the current study, we applied our established quantitative pathway-based approach to a publicly available dataset of murine male reproductive development [18] to quantify the dynamic functional changes in biological processes that characterize normal testicular development and the first wave of spermatogenesis in vivo. Through this analysis we demonstrate that our approach can quantitatively illustrate pathway dynamics throughout a complex developmental process in vivo, successfully capturing well characterized developmental milestones. The result provides a framework for quantifying perturbation of normal developmental pathways in vivo as well as anchoring emerging in vitro models of male reproductive development to in vivo pathway dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Gene Expression Data Set

For this analysis we obtained publically available temporal mouse genomic data during early testis development (gestational days (GD) 11.5, 12.5, 14.5, 16.5, and 18.5) and the first wave of spermatogenesis (postnatal days (PND) 0, 3, 6, 8, 10, 14, 18, 20, 30, 35, and 56). Gene expression intensity in testicular tissue at each timepoint was quantified using Affymetrix MGU74Av2, Bv2, and Cv2 arrays. Detailed methods of sample collection and microarray processing are available in the original papers [17, 18]. NCBI’s gene expression omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was used to retrieve the raw dataset.

Identification and Clustering of Significantly Changed Genes

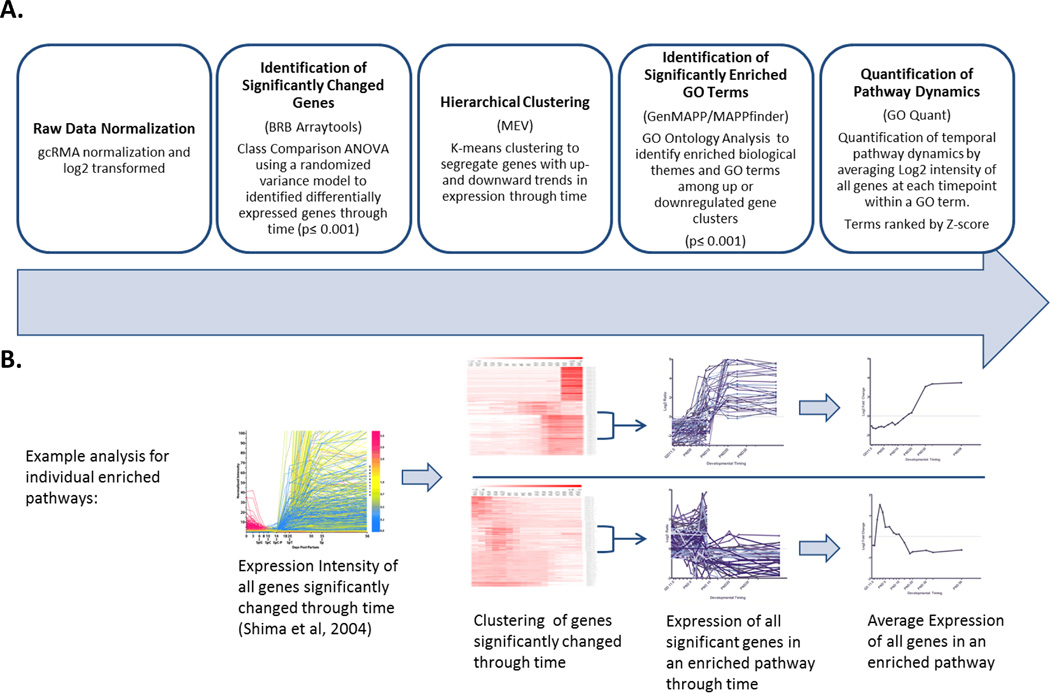

Microarray analysis was conducted based on our established quantitative pathway-based approach as shown in Figure 1 [27]. Significantly changed probes were identified using BRB ArrayTools, developed by Dr. Richard Simon and the BRB ArrayTools Development Team. Data were normalized by gcRMA normalization and log2 transformed. In order to identify significantly changed probes, we conducted an ANOVA class comparison across timepoints. Genes that were significantly altered (p ≤ 0.001) across time were selected and K-means cluster analysis was used to group genes based on the similarity of their patterns of mean expression though time. Since there are generally two directions of gene expression changes at a certain time (either up-regulation or down-regulation within a specific gene category), the average of these two different directions of gene expression alteration would mask the degree of absolute change in a pathway. For pathway analysis, we therefore separated significantly changed genes into two groups with patterns of expression tending towards consistent up- or down-regulation across time based on K-means cluster analysis [32].

Figure 1. Microarray Analysis Pipeline for Quantification of Pathway Dynamics.

A) Summary of analysis pipeline B) Illustration of data analysis process. Starting with single gene expression in testis through time (Shima et al, 2004) we normalized data and identified significantly changed genes using BRB Arraytools software, clustered genes with significantly increasing or decreasing expression through time using Multiple Experiment Viewer software (MEV), then used GO Quant software to identify GO terms enriched among these clusters and average the expression of all significantly changed genes in that pathway to produce a quantitative summary of gene expression dynamics in each GO term through time.

Identification of Enriched GO terms

We applied MAPPfinder to identify enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms at p ≤ 0.001 [33] in up- and down-regulated probes at each timepoint. Enriched GO terms were ranked by Z-score and permutation p-value [33]. As previously described, the Z-score, a statistical measure of significance for gene expression in a given group, was calculated by subtracting the number of genes expected to be randomly changed in a GO term from the observed number of changed genes in that GO term. This value was then divided by the standard deviation of the observed number of genes under a hypergeometric distribution. The equation is written out as

| (1) |

where N is the total number of genes measured, R is the total number of genes meeting the criterion that the gene be significantly changed based on an F test at significant p <= 0.001 value, n is the total number of genes in each specific GO term, and r is the number of genes meeting the criterion in this specific GO term. Complete lists of GO terms enriched among significantly upor down-regulated genes are available as supplemental data (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Quantification of Pathway Dynamics Throughout Development

To quantify the dynamic changes in GO terms through time, we used GO-Quant to link enriched GO terms to the expression values of all the significantly up- or down-regulated genes contained within the pathway. By incorporating gene expression data into the pathway analysis, we could compute the average intensity of expression among genes in each enriched GO term at each timepoint. These values at individual timepoints were then normalized to ‘average’ expression across time by subtracting the average expression intensity of genes in the GO term across all the timepoints. This yielded a log2 ratio of mean expression at each timepoint relative to the average mean expression across all timepoints. Plotting the log2 ratio for each GO term through time illustrates temporal pathway dynamics throughout development. GO terms included in the figures and tables presented here are the ten biological processes with the highest Z-scores that are relevant to each of the dominant categories selected.

Results

Our quantitative pathway analysis (summarized in Figure 1A) translates a vast amount of information on expression of single genes into a quantitative summary of temporal changes in activity across entire gene networks and biological processes described by GO terms (Figure 1B). Of the approximately 36,000 probes on the array, 9,599 probes were significantly changed through time. Significant genes were clustered into two groups based on their general expression trends using K-means clustering. This resulted in segregation of significantly changed genes into two sets: one set with overall upward trends in expression and another set with overall downward trends in expression. We then used MAPPFinder to identify GO terms describing biological processes that were enriched among each of these two gene clusters. We found 308 GO terms enriched among genes with downwards trends in expression and 112 GO terms enriched among genes with upward trends in expression. For each of these enriched GO terms, GO-Quant facilitated generation of a quantitative temporal summary of average gene expression dynamics at each timepoint among genes significantly changed in the pathway through time.

GO Terms Significantly Enriched Among Genes with Upward Trends in Expression

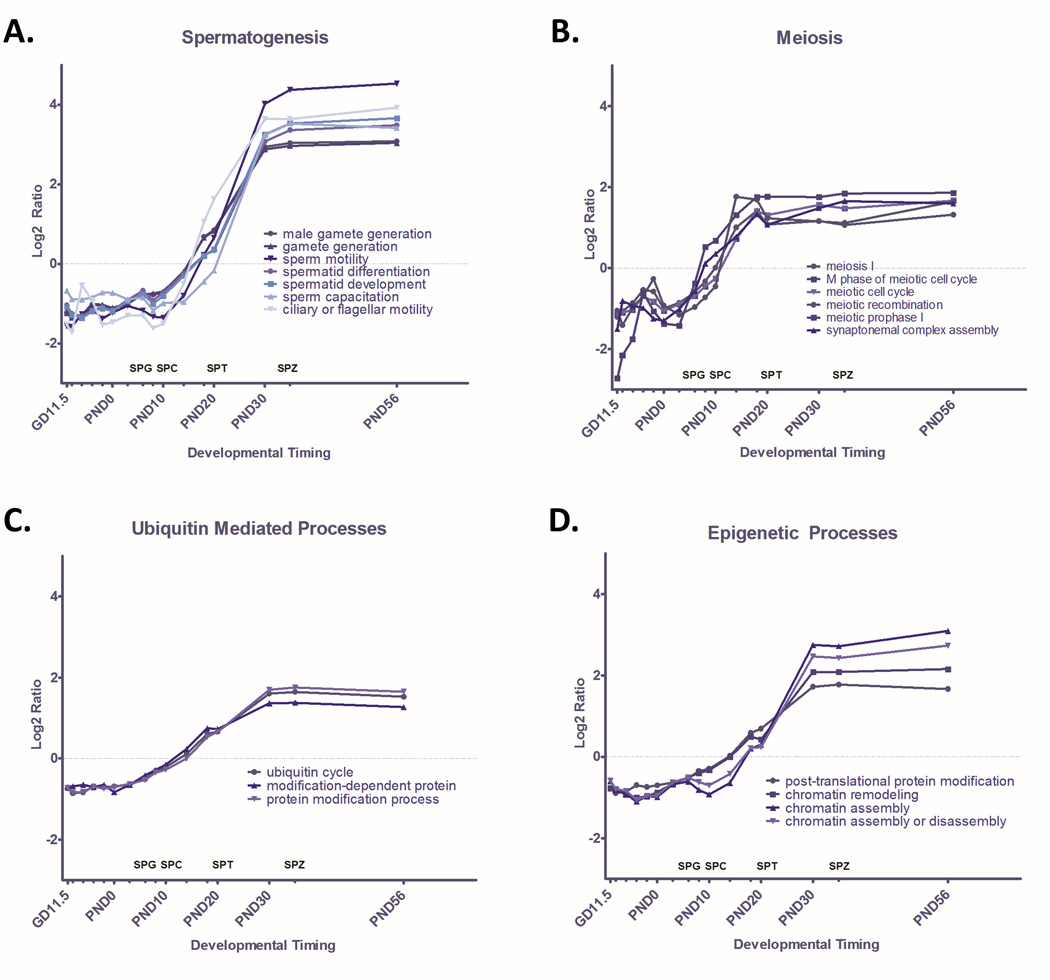

The GO terms most significantly over represented among genes with increased expression are dominated by terms associated with spermatogenesis and meiosis (Table 1). Indeed, 12 of the top 20 (60%) of significantly enriched GO terms ranked by Z-score are directly relevant to spermatogenesis or meiosis (Supplemental Table 1). Quantitative pathway analysis reveals that average gene expression in GO terms related to meiosis (Figure 2B) begins increasing around PND 3, slightly preceding the spermatogenesis and spermatid maturation signal. We see a dramatic increase in the average expression of genes in GO terms relating to spermatogenesis and spermatid development throughout testis development, capturing gene expression dynamics that are closely aligned in time with known developmental outcomes (Figure 2A). Average expression of genes involved in a host of GO terms relating to spermatid development and differentiation begin a gradual increase on PND 10 with the emergence of spermatocytes, increase around PND 20 when spermatids appear, and remain high through PND 56 as the first wave of spermatogenesis is completed and spermatozoa are produced. Simultaneously, average expression in GO terms associated with a panel of pathways related to ubiquitin mediated processes (Figure 2C) and epigenetic processes (Figure 2D) increases in parallel, with over a quarter of the genes associated with chromatin remodeling and ubiquitin cycle changing significantly through spermatogenesis.

Table 2.1.

GO Terms Enriched Among Genes With Significantly Increased Expression Through Time

| GOID | GO Name | # Genes in GO |

% of Present Genes Changed |

% of Genes Present on Array |

Z-Score | Parametric p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spermatogenesis and Sperm Maturation | ||||||

| 48232 | male gamete generation | 194 | 53.3 | 70.6 | 11.935 | 4.0E-05 |

| 7283 | spermatogenesis | 194 | 53.3 | 70.6 | 11.935 | 4.0E-05 |

| 7276 | gamete generation | 278 | 41.8 | 66.2 | 9.601 | 5.1E-05 |

| 30317 | sperm motility | 15 | 75 | 106.7 | 6.427 | 3.7E-05 |

| 48515 | spermatid differentiation | 36 | 56.2 | 88.9 | 6.202 | 7.7E-05 |

| 7286 | spermatid development | 34 | 56.7 | 88.2 | 6.067 | 3.3E-05 |

| 1539 48240 |

ciliary or flagellar motility sperm capacitation |

6 5 |

100 100 |

66.7 60 |

4.574 3.961 |

1.7E-06 3.3E-05 |

| Meiotic Cell Cycle | ||||||

| 7127 | meiosis I | 32 | 63.2 | 59.4 | 5.597 | 1.9E-04 |

| 51327 | M phase of meiotic cell cycle | 76 | 37.7 | 69.7 | 4.309 | 1.5E-04 |

| 7126 | meiosis | 76 | 37.7 | 69.7 | 4.309 | 1.5E-04 |

| 51321 | meiotic cell cycle | 77 | 37 | 70.1 | 4.21 | 1.5E-04 |

| 7131 | meiotic recombination | 17 | 75 | 23.5 | 3.212 | 6.4E-06 |

| 7128 | meiotic prophase I | 4 | 60 | 125 | 2.677 | 1.0E-07 |

| 7130 | synaptonemal complex assembly | 6 | 60 | 83.3 | 2.677 | 1.1E-04 |

| Ubiquitin Mediated Processes | ||||||

| 6512 | ubiquitin cycle | 433 | 25.3 | 83.1 | 4.837 | 7.7E-05 |

| 6511 | ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 165 | 28.9 | 69.1 | 3.767 | 6.9E-05 |

| 19941 | modification-dependent protein catabolic process | 167 | 28.4 | 69.5 | 3.654 | 6.9E-05 |

| 43632 | modification-dependent macromolecule catabolic process | 167 | 28.4 | 69.5 | 3.654 | 6.9E-05 |

| 6464 | protein modification process | 1609 | 19.5 | 78.3 | 3.535 | 8.7E-05 |

| Epigenetic Regulation | ||||||

| 43687 | post-translational protein modification | 1375 | 19.1 | 79.1 | 2.895 | 8.5E-05 |

| 6338 | chromatin remodeling | 52 | 28.9 | 73.1 | 2.169 | 8.6E-05 |

| 31497 | chromatin assembly | 142 | 25.4 | 44.4 | 2.026 | 3.6E-05 |

| 6333 | chromatin assembly or disassembly | 180 | 23.6 | 49.4 | 1.945 | 7.0E-05 |

Figure 2. Quantified Pathway Dynamics of GO Terms that Significantly Increase Through Time.

GO terms enriched among genes with significantly increasing expression (p<0.001) through time were identified through MAPPfinder. Significantly enriched GO terms (p<0.001) were ranked by Z-score and dominant themes among these terms were identified as A) Spermatogenesis, B) Meiosis, C) Ubiquitin Mediated Processes, and D) Epigenetic Processes. Dynamic change in GO terms related to each dominant theme are plotted here as the ratio of average Log2 intensity of expression of all significantly changed genes at each timepoint in a GO term over Average Log2 intensity across all timepoints for that GO term. Corresponding stages of spermatogenesis, including spermatogonia (SPG), spermatocyte (SPC), spermatid (SPT), and spermatozoa (SPZ) are indicated along the X axis.

GO Terms Significantly Enriched Among Genes with Downward Trends in Expression

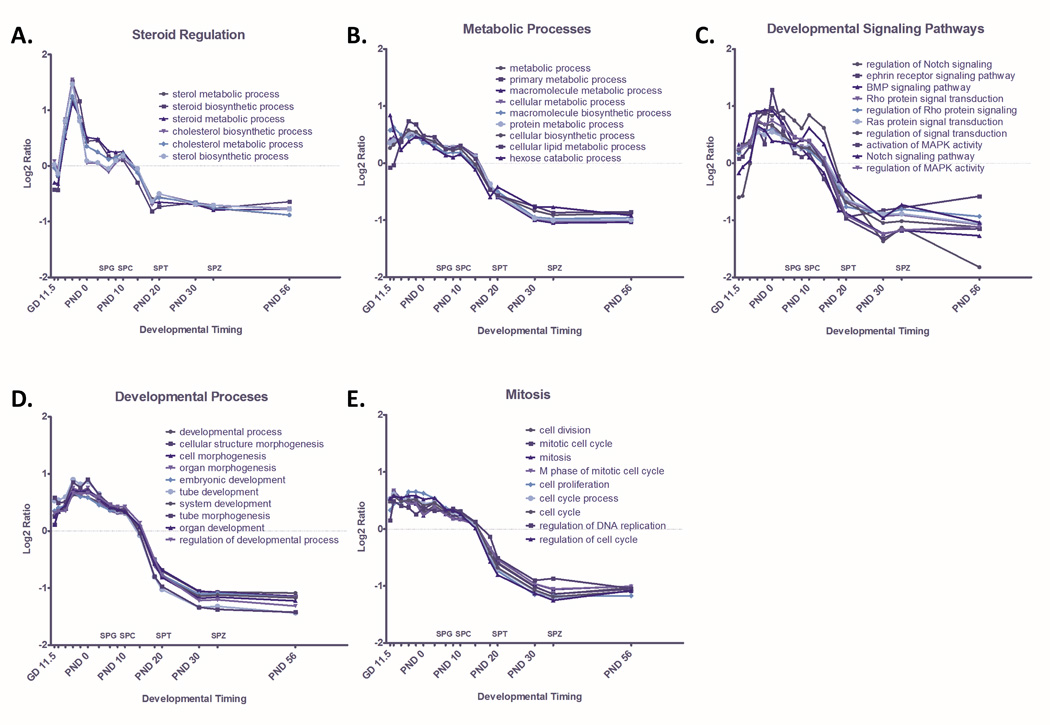

The dominant themes in GO terms enriched among genes with decreasing expression through time include developmental processes, metabolic processes, developmental signaling pathways, mitosis, and steroid regulation (Table 2). Quantitative pathway analysis illustrates dynamic changes in GO terms related to steroid regulation throughout testis development. For example, average gene expression in sterol metabolic and biosynthetic processes peak at GD 16.5, decrease before birth, and decrease further after spermatid development commences (Figure 3A). Several other catabolic and metabolic pathways, including lipid metabolism, follow a similar pattern of expression (Figure 3B).

Table 2.2.

GO Terms Enriched Among Genes With Significantly Decreased Expression Through Time

| GOID | GO Name | # Genes in GO |

% of Present Genes Changed |

% of Genes Present on Array |

Z-Score | Parametric p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid Regulation | ||||||

| 16125 | sterol metabolic process | 73 | 44.1 | 80.8 | 2.997 | 7.3E-05 |

| 6694 | steroid biosynthetic process | 75 | 46.3 | 72 | 3.237 | 5.7E-05 |

| 6695 | cholesterol biosynthetic process | 25 | 55 | 80 | 2.846 | 4.1E-05 |

| 8203 | cholesterol metabolic process | 67 | 43.4 | 79.1 | 2.729 | 6.0E-05 |

| 16126 | sterol biosynthetic process | 31 | 50 | 83.9 | 2.67 | 7.4E-05 |

| 8202 | steroid metabolic process | 145 | 36.5 | 79.3 | 2.358 | 9.8E-05 |

| Cellular Metabolism | ||||||

| 8152 | metabolic process | 8113 | 28.8 | 76.1 | 4.835 | 1.3E-04 |

| 44238 | primary metabolic process | 7338 | 29 | 75.1 | 4.83 | 1.3E-04 |

| 43170 | macromolecule metabolic process | 6411 | 28.8 | 74.7 | 3.91 | 1.3E-04 |

| 44237 | cellular metabolic process | 7311 | 28.9 | 75.4 | 4.651 | 1.3E-04 |

| 9059 | macromolecule biosynthetic process | 899 | 34.8 | 65.5 | 4.476 | 1.5E-04 |

| 19538 | protein metabolic process | 3404 | 29.4 | 74 | 3.263 | 1.3E-04 |

| 44249 | cellular biosynthetic process | 646 | 33.1 | 74.9 | 3.156 | 1.4E-04 |

| 44255 | cellular lipid metabolic process | 542 | 33.2 | 81.2 | 3.063 | 1.4E-04 |

| 19320 | hexose catabolic process | 91 | 44.2 | 57.1 | 2.839 | 1.3E-04 |

| 46365 | monosaccharide catabolic process | 91 | 44.2 | 57.1 | 2.839 | 1.3E-04 |

| Developmental Processes | ||||||

| 32502 | developmental process | 3292 | 31.8 | 75.6 | 6.268 | 1.2E-04 |

| 32989 | cellular structure morphogenesis | 485 | 39.4 | 77.9 | 5.61 | 7.9E-05 |

| 902 | cell morphogenesis | 485 | 39.4 | 77.9 | 5.61 | 7.9E-05 |

| 9887 | organ morphogenesis | 457 | 39.2 | 82.1 | 5.49 | 8.6E-05 |

| 9790 | embryonic development | 362 | 39.2 | 94.5 | 5.229 | 6.1E-05 |

| 35295 | tube development | 128 | 46.9 | 100 | 5.146 | 5.3E-05 |

| 48731 | system development | 1704 | 32.5 | 74.9 | 4.824 | 1.0E-04 |

| 35239 | tube morphogenesis | 83 | 48.9 | 106 | 4.683 | 6.2E-05 |

| 48513 | organ development | 1345 | 32.2 | 76.4 | 4.077 | 1.0E-04 |

| 50793 | regulation of developmental process | 256 | 38.8 | 85.5 | 4.039 | 7.9E-05 |

| Developmental Signaling Pathways | ||||||

| 8593 | regulation of Notch signaling pathway | 5 | 100 | 80 | 3.304 | 2.0E-05 |

| 48013 | ephrin receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 100 | 133.3 | 3.304 | 4.2E-05 |

| 30509 | BMP signaling pathway | 26 | 57.1 | 80.8 | 3.139 | 1.5E-04 |

| 7266 | Rho protein signal transduction | 102 | 41.5 | 80.4 | 3.002 | 1.6E-04 |

| 43405 | regulation of MAPK activity | 77 | 44.4 | 70.1 | 2.929 | 9.7E-05 |

| 35023 | regulation of Rho protein signal transduction | 72 | 42.2 | 88.9 | 2.781 | 1.8E-04 |

| 7265 | Ras protein signal transduction | 172 | 37.4 | 71.5 | 2.66 | 1.7E-04 |

| 9966 | regulation of signal transduction | 411 | 32.1 | 78.8 | 2.171 | 1.6E-04 |

| 187 | activation of MAPK activity | 48 | 43.8 | 66.7 | 2.164 | 9.9E-05 |

| 7219 | Notch signaling pathway | 51 | 40.9 | 86.3 | 2.113 | 5.6E-05 |

| Mitotic Cell Cycle | ||||||

| 51301 | cell division | 218 | 42.9 | 90.8 | 5.155 | 1.7E-04 |

| 278 | mitotic cell cycle | 249 | 39.6 | 81.1 | 4.133 | 1.3E-04 |

| 7067 | mitosis | 168 | 41.7 | 85.7 | 4.043 | 1.4E-04 |

| 87 | M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 170 | 41.5 | 86.5 | 4.039 | 1.4E-04 |

| 8283 | cell proliferation | 648 | 35.3 | 63 | 3.925 | 9.8E-05 |

| 22402 | cell cycle process | 646 | 34.9 | 69.2 | 3.923 | 1.4E-04 |

| 7049 | cell cycle | 762 | 33.7 | 74.4 | 3.773 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6275 | regulation of DNA replication | 19 | 70 | 52.6 | 3.083 | 1.5E-04 |

| 51726 | regulation of cell cycle | 461 | 33.5 | 60.3 | 2.523 | 1.3E-04 |

| 74 | regulation of progression through cell cycle | 459 | 33.5 | 59.9 | 2.509 | 1.3E-04 |

Figure 3. Quantified Pathway Dynamics of GO terms that Significantly Decrease Through Time.

GO terms enriched among genes with significantly decreasing expression (p<0.001) through time were identified through MAPPfinder. Significantly enriched GO terms (p<0.001) were ranked by Z-score and dominant themes among these terms were identified as A) Steroid Regulation B) Cellular Metabolism C) Developmental Signaling Pathways, D) Developmental Processes, and E) Meiosis. Dynamic change in GO terms related to each dominant theme are plotted here as the ratio of average Log2 intensity of expression of all significantly changed genes at each timepoint in a GO term over Average Log2 intensity across all timepoints for that GO term. Corresponding stages of spermatogenesis, including spermatogonia (SPG), spermatocyte (SPC), spermatid (SPT), and spermatozoa (SPZ) are indicated along the X axis.

Our analysis also reveals dynamic changes of signal transduction pathways throughout spermatogenesis (Figure 3C). Average gene expression of many developmental signaling pathways, including BMP, Notch, and MAPK signaling, are elevated towards the end of gestation and during the earliest stages of spermatogenesis, peaking between GD 16.5 and PND 3. Average expression in these developmental signaling pathways decreases dramatically between PND 14 and PND 18, as testicular formation and development give way to functional adult tissue.

GO terms for developmental processes (Figure 3D) and mitosis (Figure 3E) display a similar pattern of dramatic upregulation during peak testicular development, dropping off as testes mature and spermatogenesis progresses. For example, pathways involved in cell growth and differentiation, mitosis, and cellular morphogenesis and development, are generally elevated during gestation and the first week of life. Then, around PND 8, expression of genes in these pathways begins a gradual decrease. This decrease corresponds to the end stages of testis development and maturation and the beginning of spermatogenesis.

Discussion

Our systematic pathway-based approach distills complex genomic data into a quantitative description of pathway dynamics over the course of gonadal development and spermatogenesis. This analysis successfully captures well characterized developmental processes, offering a quantitative framework for assessing normal temporal dynamics of reproductive development and measuring any perturbation of these dynamics that could lead to pathology. Finally, by defining in vivo pathway dynamics, this analysis facilitates evaluation of the ability of emerging in vitro systems to capture important developmental pathways.

Pathway analysis captures dynamics of key events known to drive testicular development and spermatogenesis

The trends highlighted by our analysis are consistent with well characterized developmental processes described in the literature. For example, the notable peak in expression of pathways related to steroidogenesis and hormonal regulation observed in our analysis at GD 16.5 corresponds to the well characterized peak in testosterone known to drive male reproductive development [16, 34]. Furthermore, in this dataset, specific genes that are widely recognized in the literature for their roles in steroidogenesis, including, star, 3β-HSD, and C/EBPβ [35, 36] follow temporal expression patterns that are consistent with the average expression patterns reflected in pathway analysis. The significant increase in steroidogenesis during this phase has previously been identified as a critical initiator of testis development and masculinization of the fetus [16, 34]. Expression of a host of genes in the mouse reproductive tract has been shown to be modulated by estrogen and testosterone [37].

The dramatic proliferation of somatic cells that occurs early in testis development plays a role in promoting the male fate by increasing the number of SRY-producing cells and marks a key difference between male and female development [38]. Accordingly, in this analysis, we see that pathways that promote proliferation and mitosis are expressed in developing testes and then downregulated as functionally mature testes begin spermatogenesis. Conversely, meiosis in the testis does not begin until around PND5, with the initiation of the first wave of spermatogenesis [39]. This is clearly illustrated at the pathway level in our analysis. In addition, several meiosis-specific genes described in the literature, such as the family of synaptonemal complex proteins [40] follow expression trends consistent with overall pathway trends.

The onset of meiosis in this analysis is followed by a dramatic increase in expression of a host of specific genes known to play an important role in spermatogenesis. For example, by PND 30 there is a sharp increase in gene expression of protamines 1 and 2 and the transition proteins that facilitate the switch between histones and sperm-specific protamines [40]. General expression dynamics of GO terms related to spermatogenesis are consistent with expression dynamics for these genes with well-characterized roles in spermatogenesis.

During spermatogenesis, chromatin restructuring facilitates sperm compaction and regulation of DNA methylation [41, 42]. Precise regulation of these epigenetic processes is essential for sperm development as well as for appropriate expression of the paternal genome in the developing embryo [42]. The ubiquitin system plays an important role in performing the histone modifications that underlie this chromatin restructuring [43]. The prominent increase in expression of genes associated with ubiquitin mediated processes and epigenetic processes that is observed concurrently with spermatogenesis in our analysis illustrates the temporal dynamics of these well-described regulatory processes.

Our analysis also successfully captures the important role of signal transduction pathways in regulating development. At least 17 highly conserved signaling pathways are now recognized for their central role in guiding developmental processes [12, 44]. Many of these signaling pathways are specifically implicated in guiding the processes of gonadal differentiation and testicular development [45] and germ cell differentiation [46]. In the current analysis, we capture the increased expression of genes involved in these signal transduction pathways throughout gestation and testicular maturation. These signaling pathways are then downregulated as testis tissue achieves maturation and begins the process of meiosis and spermatogenesis.

Pathway analysis can facilitate discovery of new roles for pathways dynamically changed in testicular development

In addition to accurately illustrating these well characterized developmental processes, quantitative pathway analysis is also a powerful tool for providing new insight into the stagespecific regulation of signaling pathways involved in the unique and complex processes of gonadal differentiation and spermatogenesis. The precise balance of these signaling pathways is hypothesized to play a key role in male development by initiating the differentiation of the fetal Leydig cells that produce masculinizing hormones [47]. The current analysis shows a wide range of signal transduction pathways that go through dramatic changes in expression in testicular tissue over the course of the first wave of spermatogenesis. Further investigation of the fluctuations in these signaling pathways over time could provide insight into their roles in the regulation and maintenance of spermatogenesis.

We also find that pathways related to cellular metabolism of lipids and proteins follow the same pattern of expression as steroidogenesis pathways during spermatogenesis. If these pathways are in fact linked, this is consistent with the hypothesis that cellular metabolism pathways are a target of androgen action, allowing androgens to modulate the testis environment to promote spermatogenesis [16]. These observations illustrate that our pathway-based approach can provide quantitative information on the dynamic changes seen in a range of signaling pathways over the course of development. Deeper exploration of this pathway analysis may reveal additional novel pathways that are important in reproductive development.

Benefits and drawbacks of the quantitative pathway-based approach

There are many benefits to applying a pathway based approach to analyze temporal gene expression data. For example, we reduce the potential for overlooking key pathways whose subtle changes have large effects by considering the pathway as a whole as opposed to individual genes. We also reduce the amount of statistical noise, as entire gene networks are far less likely than individual genes to be significantly increased simply by chance. It is important to note that while average pathway expression provides an informative summary of pathway dynamics driving developmental processes, this method is not ideal for identification and characterization of single genes that serve as key developmental regulators. In addition, the quality of a pathway-based analysis is limited by the quality of the curation of each pathway. Indeed, there are several pathways enriched in our analysis (e.g. heart development and neural tube development) that are likely to be an artifact of genes that have simultaneous roles in multiple pathways or signal transduction that is highly conserved across a diverse range of developmental processes.

Applications for developmental toxicology: defining sensitive phases of development and generating complex, context dependent Adverse Outcome Pathways

In addition to providing insight into normal gonadal development and spermatogenesis, this quantitative gene ontology analysis offers a new lens through which to evaluate developmental pathology. This will be a particularly valuable tool for our field of developmental toxicology. Understanding the dynamics of signaling pathways can further define key phases of susceptibility to environmental factors. For example quantitative characterization of the pathway dynamics that drive steroid regulation can shed light on key windows of susceptibility of this process to endocrine disrupting chemicals [7, 48].

The challenge of regulatory chemical testing requirements and the vast number of chemicals yet to be tested will require innovative computational toxicology methods [49, 50]. Toxicity-related alterations in gene transcription and biological pathway dynamics have been proposed as valuable metrics for chemical risk assessment that could be generated by highthroughput methods [51, 52]. To that end, a quantitative pathway-based approach can be applied to predict and measure the effects of chemical exposure on signaling pathway dynamics. This approach is a powerful way to quantify changes in the developmental dynamics of signaling pathways in response to genetic mutations and environmental factors. Changes in the peaks, slopes and duration of the dynamic expression patterns of signaling pathways in response to toxicant exposure will provide a sensitive measure of reproductive developmental toxicity and offer insight into mechanisms of toxicity. Quantitative pathway-based characterization of signaling pathway dynamics could also inform mathematical models for in silico simulation of the specific impacts of gene changes or environmental exposures on developmental outcomes. Furthermore, quantifying the perturbation of developmental pathway dynamics in response to toxicant exposures could facilitate articulation of “Adverse Outcome Pathways”, which are emerging as an increasingly valuable tool for translating toxicological data for risk assessment [53]. Therefore, in addition to shedding light on normal developmental dynamics, this quantitative pathway- based approach provides a framework for quantifying deviation from normal developmental processes.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.3.

Full list of GO Terms Enriched Among Genes With Significantly Increased Expression Through Time

| GOID | GO Name | # Genes in GO |

%Genes Changed |

%Genes Present |

Z- Score |

Parametric p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48232 | male gamete generation | 194 | 53.3 | 70.6 | 11.94 | 4.0E-05 |

| 7283 | Spermatogenesis | 194 | 53.3 | 70.6 | 11.94 | 4.0E-05 |

| 19953 | sexual reproduction | 327 | 45 | 67.9 | 11.87 | 4.6E-05 |

| 3 | Reproduction | 492 | 35.5 | 65.2 | 9.62 | 5.2E-05 |

| 7276 | gamete generation | 278 | 41.8 | 66.2 | 9.60 | 5.1E-05 |

| 9566 | Fertilization | 48 | 62.9 | 72.9 | 7.55 | 2.0E-05 |

| 7338 | single fertilization | 48 | 61.8 | 70.8 | 7.27 | 2.1E-05 |

| 30317 | sperm motility | 15 | 75 | 106.7 | 6.43 | 3.7E-05 |

| 48515 | spermatid differentiation | 36 | 56.2 | 88.9 | 6.20 | 7.7E-05 |

| 7286 | spermatid development | 34 | 56.7 | 88.2 | 6.07 | 3.3E-05 |

| 7127 | meiosis I | 32 | 63.2 | 59.4 | 5.60 | 1.9E-04 |

| 6457 | protein folding | 238 | 29.5 | 72.7 | 4.84 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6512 | ubiquitin cycle | 433 | 25.3 | 83.1 | 4.84 | 7.7E-05 |

| 35036 | sperm-egg recognition | 12 | 66.7 | 100 | 4.78 | 1.5E-07 |

| 1539 | ciliary or flagellar motility | 6 | 100 | 66.7 | 4.57 | 1.7E-06 |

| 7129 | Synapsis | 9 | 75 | 88.9 | 4.54 | 2.2E-04 |

| 9988 | cell-cell recognition | 13 | 61.5 | 100 | 4.47 | 1.5E-07 |

| 51327 | M phase of meiotic cell cycle | 76 | 37.7 | 69.7 | 4.31 | 1.5E-04 |

| 7126 | Meiosis | 76 | 37.7 | 69.7 | 4.31 | 1.5E-04 |

| 7339 | binding of sperm to zona pellucida | 11 | 63.6 | 100 | 4.30 | 1.6E-07 |

| 51321 | meiotic cell cycle | 77 | 37 | 70.1 | 4.21 | 1.5E-04 |

| 48240 | sperm capacitation | 5 | 100 | 60 | 3.96 | 3.3E-05 |

| 6644 | phospholipid metabolic process | 127 | 30.1 | 81.1 | 3.90 | 9.7E-05 |

| 2483 | antigen processing and presentation of endogenous peptide antigen | 8 | 80 | 62.5 | 3.90 | 4.8E-05 |

| 19885 | antigen processing and presentation of endogenous peptide antigen via MHC class I | 8 | 80 | 62.5 | 3.90 | 4.8E-05 |

| 30163 | protein catabolic process | 220 | 27.2 | 71.8 | 3.85 | 9.4E-05 |

| 6643 | membrane lipid metabolic process | 173 | 28 | 76.3 | 3.77 | 9.0E-05 |

| 6511 | ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 165 | 28.9 | 69.1 | 3.77 | 6.9E-05 |

| 19941 | modification-dependent protein catabolic process | 167 | 28.4 | 69.5 | 3.65 | 6.9E-05 |

| 43632 | modification-dependent macromolecule catabolic process | 167 | 28.4 | 69.5 | 3.65 | 6.9E-05 |

| 8654 | phospholipid biosynthetic process | 67 | 33.9 | 83.6 | 3.65 | 3.7E-05 |

| 6352 | transcription initiation | 45 | 37.8 | 82.2 | 3.62 | 5.1E-05 |

| 44265 | cellular macromolecule catabolic process | 319 | 25.1 | 64.9 | 3.58 | 5.9E-05 |

| 6516 | glycoprotein catabolic process | 16 | 62.5 | 50 | 3.58 | 1.4E-04 |

| 6913 | nucleocytoplasmic transport | 127 | 29.7 | 71.7 | 3.55 | 1.2E-04 |

| 51603 | proteolysis involved in cellular protein catabolic process | 170 | 28 | 69.4 | 3.54 | 6.9E-05 |

| 6464 | protein modification process | 1609 | 19.5 | 78.3 | 3.54 | 8.7E-05 |

| 6508 | proteolysis | 806 | 21.3 | 70.5 | 3.49 | 8.2E-05 |

| 6611 | protein export from nucleus | 16 | 50 | 87.5 | 3.46 | 1.3E-04 |

| 9057 | macromolecule catabolic process | 387 | 23.8 | 67.2 | 3.46 | 7.8E-05 |

| 22414 | reproductive process | 248 | 26.1 | 63.3 | 3.46 | 5.4E-05 |

| 44257 | cellular protein catabolic process | 172 | 27.5 | 69.8 | 3.43 | 6.9E-05 |

| 46467 | membrane lipid biosynthetic process | 85 | 31.3 | 78.8 | 3.42 | 3.4E-05 |

| 65004 | protein-DNA complex assembly | 172 | 29.2 | 51.7 | 3.39 | 5.0E-05 |

| 7342 | fusion of sperm to egg plasma membrane | 9 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 3.38 | 8.0E-07 |

| 51169 | nuclear transport | 115 | 29.6 | 70.4 | 3.34 | 1.3E-04 |

| 43412 | biopolymer modification | 1677 | 19.2 | 78.1 | 3.31 | 8.6E-05 |

| 7017 | microtubule-based process | 216 | 25.6 | 72.2 | 3.28 | 9.2E-05 |

| 44267 | cellular protein metabolic process | 3258 | 18.2 | 74 | 3.26 | 9.3E-05 |

| 45862 | positive regulation of proteolysis | 5 | 75 | 80 | 3.21 | 3.1E-05 |

| 7131 | meiotic recombination | 17 | 75 | 23.5 | 3.21 | 6.4E-06 |

| 6003 | fructose 2\,6-bisphosphate metabolic process | 4 | 75 | 100 | 3.21 | 2.5E-04 |

| 9894 | regulation of catabolic process | 19 | 50 | 63.2 | 3.21 | 2.1E-05 |

| 44260 | cellular macromolecule metabolic process | 3301 | 18.1 | 74.1 | 3.14 | 9.3E-05 |

| 19538 | protein metabolic process | 3404 | 18.1 | 74 | 3.12 | 9.2E-05 |

| 6986 | response to unfolded protein | 62 | 38.5 | 41.9 | 3.12 | 3.9E-05 |

| 51789 | response to protein stimulus | 62 | 38.5 | 41.9 | 3.12 | 3.9E-05 |

| 19318 | hexose metabolic process | 174 | 26.5 | 67.2 | 3.09 | 7.0E-05 |

| 22403 | cell cycle phase | 289 | 23.5 | 78.2 | 3.06 | 1.2E-04 |

| 9056 | catabolic process | 639 | 21 | 72.1 | 2.97 | 7.2E-05 |

| 279 | M phase | 232 | 23.9 | 81 | 2.97 | 1.3E-04 |

| 7340 | acrosome reaction | 12 | 57.1 | 58.3 | 2.96 | 4.5E-07 |

| 45026 | plasma membrane fusion | 10 | 57.1 | 70 | 2.96 | 8.0E-07 |

| 19883 | antigen processing and presentation of endogenous antigen | 11 | 57.1 | 63.6 | 2.96 | 4.8E-05 |

| 5996 | monosaccharide metabolic process | 178 | 25.8 | 67.4 | 2.93 | 7.0E-05 |

| 42176 | regulation of protein catabolic process | 14 | 50 | 71.4 | 2.93 | 2.5E-05 |

| 6515 | misfolded or incompletely synthesized protein catabolic process | 19 | 50 | 52.6 | 2.93 | 1.9E-04 |

| 30433 | ER-associated protein catabolic process | 18 | 50 | 55.6 | 2.93 | 1.9E-04 |

| 6493 | protein amino acid O-linked glycosylation | 16 | 50 | 62.5 | 2.93 | 1.7E-04 |

| 6367 | transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 25 | 40 | 80 | 2.92 | 7.1E-05 |

| 43687 | post-translational protein modification | 1375 | 19.1 | 79.1 | 2.90 | 8.5E-05 |

| 51170 | nuclear import | 80 | 29.5 | 76.2 | 2.87 | 1.2E-04 |

| 43285 | biopolymer catabolic process | 285 | 23.2 | 71.2 | 2.78 | 9.5E-05 |

| 30503 | regulation of cell redox homeostasis | 7 | 60 | 71.4 | 2.68 | 1.8E-05 |

| 7128 | meiotic prophase I | 4 | 60 | 125 | 2.68 | 1.0E-07 |

| 7130 | synaptonemal complex assembly | 6 | 60 | 83.3 | 2.68 | 1.1E-04 |

| 51324 | prophase | 4 | 60 | 125 | 2.68 | 1.0E-07 |

| 6000 | fructose metabolic process | 13 | 60 | 38.5 | 2.68 | 2.5E-04 |

| 6072 | glycerol-3-phosphate metabolic process | 7 | 60 | 71.4 | 2.68 | 4.7E-05 |

| 42787 | protein ubiquitination during ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 5 | 60 | 100 | 2.68 | 1.2E-04 |

| 9191 | ribonucleoside diphosphate catabolic process | 5 | 60 | 100 | 2.68 | 1.2E-05 |

| 46470 | phosphatidylcholine metabolic process | 7 | 60 | 71.4 | 2.68 | 3.4E-04 |

| 31365 | N-terminal protein amino acid modification | 6 | 60 | 83.3 | 2.68 | 3.6E-04 |

| 6606 | protein import into nucleus | 79 | 28.8 | 74.7 | 2.68 | 1.2E-04 |

| 7001 | chromosome organization and biogenesis (sensu Eukaryota) | 390 | 22.1 | 64.9 | 2.66 | 1.1E-04 |

| 45582 | positive regulation of T cell differentiation | 11 | 45.5 | 100 | 2.66 | 1.4E-04 |

| 51168 | nuclear export | 40 | 34.6 | 65 | 2.58 | 2.1E-04 |

| 6096 | glycolysis | 76 | 30.2 | 56.6 | 2.54 | 1.8E-05 |

| 6006 | glucose metabolic process | 133 | 25.8 | 66.9 | 2.53 | 4.8E-05 |

| 51276 | chromosome organization and biogenesis | 399 | 21.5 | 66.4 | 2.45 | 1.1E-04 |

| 7018 | microtubule-based movement | 115 | 26.3 | 66.1 | 2.45 | 6.6E-05 |

| 18342 | protein prenylation | 17 | 41.7 | 70.6 | 2.42 | 1.2E-04 |

| 16311 | dephosphorylation | 146 | 24 | 82.9 | 2.38 | 1.4E-04 |

| 48002 | antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen | 37 | 30.6 | 97.3 | 2.37 | 1.1E-04 |

| 46164 | alcohol catabolic process | 93 | 27.8 | 58.1 | 2.35 | 2.7E-05 |

| 8037 | cell recognition | 41 | 31.2 | 78 | 2.35 | 3.8E-07 |

| 6944 | membrane fusion | 31 | 37.5 | 51.6 | 2.34 | 8.7E-05 |

| 18346 | protein amino acid prenylation | 13 | 44.4 | 69.2 | 2.32 | 1.5E-04 |

| 46165 | alcohol biosynthetic process | 27 | 35 | 74.1 | 2.31 | 7.4E-05 |

| 46364 | monosaccharide biosynthetic process | 27 | 35 | 74.1 | 2.31 | 7.4E-05 |

| 19319 | hexose biosynthetic process | 27 | 35 | 74.1 | 2.31 | 7.4E-05 |

| 6066 | alcohol metabolic process | 300 | 21.6 | 72.7 | 2.23 | 7.1E-05 |

| 7049 | cell cycle | 762 | 19.4 | 74.4 | 2.22 | 1.1E-04 |

| 6007 | glucose catabolic process | 86 | 27.5 | 59.3 | 2.22 | 2.5E-05 |

| 51252 | regulation of RNA metabolic process | 17 | 38.5 | 76.5 | 2.20 | 3.5E-04 |

| 44248 | cellular catabolic process | 510 | 20.2 | 69.8 | 2.18 | 6.4E-05 |

| 32446 | protein modification by small protein conjugation | 75 | 26.2 | 81.3 | 2.17 | 6.3E-05 |

| 6338 | chromatin remodeling | 52 | 28.9 | 73.1 | 2.17 | 8.6E-05 |

| 46365 | monosaccharide catabolic process | 91 | 26.9 | 57.1 | 2.14 | 2.5E-05 |

| 19320 | hexose catabolic process | 91 | 26.9 | 57.1 | 2.14 | 2.5E-05 |

| 46916 | transition metal ion homeostasis | 49 | 30 | 61.2 | 2.08 | 6.1E-05 |

| 31497 | chromatin assembly | 142 | 25.4 | 44.4 | 2.03 | 3.6E-05 |

| 6333 | chromatin assembly or disassembly | 180 | 23.6 | 49.4 | 1.95 | 7.0E-05 |

Table 2.4.

Full list of GO Terms Enriched Among Genes With Significantly Decreased Expression Through Time

| GOID | GO Name | # Genes in GO |

% Genes Changed |

% Genes Present |

Z- Score |

Parametric p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9653 | anatomical structure morphogenesis | 1089 | 37.5 | 80.2 | 7.35 | 8.8E-05 |

| 9987 | cellular process | 12349 | 28.7 | 67 | 6.42 | 1.3E-04 |

| 32502 | developmental process | 3292 | 31.8 | 75.6 | 6.27 | 1.2E-04 |

| 48856 | anatomical structure development | 2002 | 33.4 | 74.8 | 6.16 | 9.9E-05 |

| 9058 | biosynthetic process | 1471 | 34.6 | 70 | 5.87 | 1.4E-04 |

| 902 | cell morphogenesis | 485 | 39.4 | 77.9 | 5.61 | 7.9E-05 |

| 32989 | cellular structure morphogenesis | 485 | 39.4 | 77.9 | 5.61 | 7.9E-05 |

| 9887 | organ morphogenesis | 457 | 39.2 | 82.1 | 5.49 | 8.6E-05 |

| 7167 | enzyme linked receptor protein signaling pathway | 278 | 43.7 | 71.6 | 5.42 | 9.7E-05 |

| 30036 | actin cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 196 | 46.6 | 74.5 | 5.42 | 7.1E-05 |

| 1525 | angiogenesis | 132 | 48.3 | 89.4 | 5.29 | 6.2E-05 |

| 9790 | embryonic development | 362 | 39.2 | 94.5 | 5.23 | 6.1E-05 |

| 30029 | actin filament-based process | 207 | 45.2 | 74.9 | 5.18 | 7.0E-05 |

| 7507 | heart development | 133 | 45.8 | 108.3 | 5.18 | 5.3E-05 |

| 51301 | cell division | 218 | 42.9 | 90.8 | 5.15 | 1.7E-04 |

| 35295 | tube development | 128 | 46.9 | 100 | 5.15 | 5.3E-05 |

| 7275 | multicellular organismal development | 2140 | 31.9 | 77.5 | 5.05 | 1.1E-04 |

| 48646 | anatomical structure formation | 173 | 44.4 | 92.5 | 5.04 | 7.4E-05 |

| 1944 | vasculature development | 190 | 42.9 | 93.2 | 4.87 | 7.2E-05 |

| 16043 | cellular component organization and biogenesis | 2656 | 31.4 | 70.2 | 4.86 | 1.2E-04 |

| 8152 | metabolic process | 8113 | 28.8 | 76.1 | 4.83 | 1.3E-04 |

| 44238 | primary metabolic process | 7338 | 29 | 75.1 | 4.83 | 1.3E-04 |

| 48731 | system development | 1704 | 32.5 | 74.9 | 4.82 | 1.0E-04 |

| 48514 | blood vessel morphogenesis | 162 | 44 | 92.6 | 4.78 | 7.5E-05 |

| 1568 | blood vessel development | 187 | 42.5 | 93 | 4.71 | 7.3E-05 |

| 35239 | tube morphogenesis | 83 | 48.9 | 106 | 4.68 | 6.2E-05 |

| 55008 | cardiac muscle morphogensis | 4 | 100 | 200 | 4.67 | 5.5E-05 |

| 44237 | cellular metabolic process | 7311 | 28.9 | 75.4 | 4.65 | 1.3E-04 |

| 1763 | morphogenesis of a branching structure | 49 | 54.7 | 108.2 | 4.59 | 6.3E-05 |

| 9059 | macromolecule biosynthetic process | 899 | 34.8 | 65.5 | 4.48 | 1.5E-04 |

| 48754 | branching morphogenesis of a tube | 46 | 55.1 | 106.5 | 4.48 | 5.1E-05 |

| 55010 | ventricular cardiac muscle morphogenesis | 4 | 100 | 175 | 4.37 | 5.0E-05 |

| 7399 | nervous system development | 658 | 35.2 | 74.3 | 4.25 | 1.0E-04 |

| 65007 | biological regulation | 4497 | 29.6 | 74.5 | 4.21 | 1.2E-04 |

| 22610 | biological adhesion | 645 | 35.4 | 70.5 | 4.20 | 8.5E-05 |

| 7155 | cell adhesion | 645 | 35.4 | 70.5 | 4.20 | 8.5E-05 |

| 278 | mitotic cell cycle | 249 | 39.6 | 81.1 | 4.13 | 1.3E-04 |

| 7178 | transmembrane receptor protein serine/threonine kinase signaling pathway | 87 | 50 | 71.3 | 4.13 | 1.2E-04 |

| 15669 | gas transport | 17 | 81.8 | 64.7 | 4.12 | 8.7E-05 |

| 50789 | regulation of biological process | 4133 | 29.7 | 75.1 | 4.11 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6996 | organelle organization and biogenesis | 1201 | 33.1 | 65.9 | 4.10 | 1.1E-04 |

| 30865 | cortical cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 14 | 76.9 | 92.9 | 4.08 | 1.5E-04 |

| 48513 | organ development | 1345 | 32.2 | 76.4 | 4.08 | 1.0E-04 |

| 7067 | mitosis | 168 | 41.7 | 85.7 | 4.04 | 1.4E-04 |

| 87 | M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 170 | 41.5 | 86.5 | 4.04 | 1.4E-04 |

| 50793 | regulation of developmental process | 256 | 38.8 | 85.5 | 4.04 | 7.9E-05 |

| 7169 | transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway | 177 | 42.1 | 75.1 | 4.00 | 8.3E-05 |

| 9880 | embryonic pattern specification | 41 | 55.3 | 92.7 | 3.96 | 7.9E-05 |

| 8283 | cell proliferation | 648 | 35.3 | 63 | 3.93 | 9.8E-05 |

| 22402 | cell cycle process | 646 | 34.9 | 69.2 | 3.92 | 1.4E-04 |

| 43170 | macromolecule metabolic process | 6411 | 28.8 | 74.7 | 3.91 | 1.3E-04 |

| 22603 | regulation of anatomical structure morphogenesis | 46 | 53.7 | 89.1 | 3.89 | 3.8E-05 |

| 8360 | regulation of cell shape | 46 | 53.7 | 89.1 | 3.88 | 3.8E-05 |

| 22604 | regulation of cell morphogenesis | 46 | 53.7 | 89.1 | 3.88 | 3.8E-05 |

| 6412 | translation | 656 | 35.2 | 61.4 | 3.87 | 1.4E-04 |

| 48644 | muscle morphogenesis | 6 | 80 | 166.7 | 3.80 | 5.5E-05 |

| 7049 | cell cycle | 762 | 33.7 | 74.4 | 3.77 | 1.3E-04 |

| 8150 | biological_process | 14509 | 27.6 | 67.7 | 3.77 | 1.3E-04 |

| 30323 | respiratory tube development | 54 | 51.1 | 87 | 3.76 | 3.3E-05 |

| 22403 | cell cycle phase | 289 | 37.6 | 78.2 | 3.69 | 1.2E-04 |

| 7010 | cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 504 | 35.5 | 68.3 | 3.67 | 9.3E-05 |

| 30900 | forebrain development | 65 | 46.3 | 103.1 | 3.60 | 8.3E-05 |

| 31032 | actomyosin structure organization and biogenesis | 25 | 63.2 | 76 | 3.58 | 8.3E-05 |

| 30324 | lung development | 53 | 50 | 86.8 | 3.55 | 3.5E-05 |

| 9792 | embryonic development ending in birth or egg hatching | 149 | 39.2 | 102.7 | 3.48 | 4.8E-05 |

| 15671 | oxygen transport | 16 | 77.8 | 56.2 | 3.45 | 1.1E-04 |

| 43009 | chordate embryonic development | 147 | 39.1 | 102.7 | 3.42 | 4.9E-05 |

| 279 | M phase | 232 | 37.8 | 81 | 3.41 | 1.3E-04 |

| 51128 | regulation of cellular component organization and biogenesis | 68 | 46.6 | 85.3 | 3.40 | 9.8E-05 |

| 50794 | regulation of cellular process | 3752 | 29.3 | 74.9 | 3.39 | 1.2E-04 |

| 45765 | regulation of angiogenesis | 34 | 55.6 | 79.4 | 3.37 | 1.5E-04 |

| 8593 | regulation of Notch signaling pathway | 5 | 100 | 80 | 3.30 | 2.0E-05 |

| 48013 | ephrin receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 100 | 133.3 | 3.30 | 4.2E-05 |

| 48468 | cell development | 1610 | 30.8 | 74.2 | 3.27 | 1.3E-04 |

| 19538 | protein metabolic process | 3404 | 29.4 | 74 | 3.26 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6817 | phosphate transport | 84 | 44.6 | 77.4 | 3.25 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6694 | steroid biosynthetic process | 75 | 46.3 | 72 | 3.24 | 5.7E-05 |

| 6270 | DNA replication initiation | 26 | 64.3 | 53.8 | 3.17 | 1.4E-04 |

| 44249 | cellular biosynthetic process | 646 | 33.1 | 74.9 | 3.16 | 1.4E-04 |

| 30509 | BMP signaling pathway | 26 | 57.1 | 80.8 | 3.14 | 1.5E-04 |

| 6729 | tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthetic process | 6 | 83.3 | 100 | 3.13 | 1.8E-04 |

| 45995 | regulation of embryonic development | 7 | 83.3 | 85.7 | 3.13 | 2.1E-06 |

| 46146 | tetrahydrobiopterin metabolic process | 6 | 83.3 | 100 | 3.13 | 1.8E-04 |

| 51291 | protein heterooligomerization | 10 | 83.3 | 60 | 3.13 | 2.8E-05 |

| 8064 | regulation of actin polymerization and/or depolymerization | 41 | 51.6 | 75.6 | 3.12 | 9.1E-05 |

| 30832 | regulation of actin filament length | 42 | 51.6 | 73.8 | 3.12 | 9.1E-05 |

| 48546 | digestive tract morphogenesis | 10 | 66.7 | 120 | 3.12 | 7.8E-06 |

| 51169 | nuclear transport | 115 | 42 | 70.4 | 3.09 | 9.8E-05 |

| 9220 | pyrimidine ribonucleotide biosynthetic process | 16 | 70 | 62.5 | 3.08 | 6.8E-05 |

| 6275 | regulation of DNA replication | 19 | 70 | 52.6 | 3.08 | 1.5E-04 |

| 30866 | cortical actin cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 11 | 70 | 90.9 | 3.08 | 1.9E-04 |

| 8088 | axon cargo transport | 14 | 70 | 71.4 | 3.08 | 8.9E-05 |

| 7439 | ectodermal gut development | 8 | 75 | 100 | 3.08 | 1.0E-05 |

| 48567 | ectodermal gut morphogenesis | 8 | 75 | 100 | 3.08 | 1.0E-05 |

| 44255 | cellular lipid metabolic process | 542 | 33.2 | 81.2 | 3.06 | 1.4E-04 |

| 32990 | cell part morphogenesis | 249 | 36.3 | 80.7 | 3.06 | 1.0E-04 |

| 48858 | cell projection morphogenesis | 249 | 36.3 | 80.7 | 3.06 | 1.0E-04 |

| 30030 | cell projection organization and biogenesis | 249 | 36.3 | 80.7 | 3.06 | 1.0E-04 |

| 6403 | RNA localization | 49 | 50 | 69.4 | 3.05 | 1.7E-04 |

| 6790 | sulfur metabolic process | 78 | 45.3 | 67.9 | 3.04 | 1.0E-04 |

| 7266 | Rho protein signal transduction | 102 | 41.5 | 80.4 | 3.00 | 1.6E-04 |

| 16125 | sterol metabolic process | 73 | 44.1 | 80.8 | 3.00 | 7.3E-05 |

| 1501 | skeletal development | 205 | 37.6 | 72.7 | 2.98 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6221 | pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthetic process | 22 | 58.8 | 77.3 | 2.98 | 9.7E-05 |

| 30154 | cell differentiation | 2098 | 29.9 | 78.6 | 2.97 | 1.2E-04 |

| 48869 | cellular developmental process | 2098 | 29.9 | 78.6 | 2.97 | 1.2E-04 |

| 904 | cellular morphogenesis during differentiation | 182 | 37.8 | 78.6 | 2.97 | 1.1E-04 |

| 48332 | mesoderm morphogenesis | 24 | 51.9 | 112.5 | 2.94 | 8.7E-05 |

| 43405 | regulation of MAPK activity | 77 | 44.4 | 70.1 | 2.93 | 9.7E-05 |

| 46164 | alcohol catabolic process | 93 | 44.4 | 58.1 | 2.93 | 1.3E-04 |

| 59 | protein import into nucleus\, docking | 15 | 60 | 100 | 2.90 | 1.6E-04 |

| 51261 | protein depolymerization | 34 | 50 | 88.2 | 2.87 | 9.3E-05 |

| 7015 | actin filament organization | 50 | 47.4 | 76 | 2.86 | 3.9E-05 |

| 7179 | transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling pathway | 57 | 47.4 | 66.7 | 2.86 | 1.1E-04 |

| 15931 | nucleobase\, nucleoside\, nucleotide and nucleic acid transport | 54 | 47.4 | 70.4 | 2.86 | 2.4E-04 |

| 35112 | genitalia morphogenesis | 1 | 100 | 300 | 2.86 | 2.3E-07 |

| 7213 | acetylcholine receptor signaling\, muscarinic pathway | 6 | 100 | 50 | 2.86 | 1.8E-05 |

| 48010 | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling pathway | 2 | 100 | 150 | 2.86 | 2.0E-05 |

| 30513 | positive regulation of BMP signaling pathway | 3 | 100 | 100 | 2.86 | 2.5E-04 |

| 31529 | ruffle organization and biogenesis | 3 | 100 | 100 | 2.86 | 3.4E-04 |

| 6290 | pyrimidine dimer repair | 4 | 100 | 75 | 2.86 | 3.1E-05 |

| 6435 | threonyl-tRNA aminoacylation | 3 | 100 | 100 | 2.86 | 9.7E-05 |

| 7043 | intercellular junction assembly | 9 | 100 | 33.3 | 2.86 | 1.4E-06 |

| 6598 | polyamine catabolic process | 3 | 100 | 100 | 2.86 | 1.7E-04 |

| 30538 | embryonic genitalia morphogenesis | 1 | 100 | 300 | 2.86 | 2.3E-07 |

| 6695 | cholesterol biosynthetic process | 25 | 55 | 80 | 2.85 | 4.1E-05 |

| 46365 | monosaccharide catabolic process | 91 | 44.2 | 57.1 | 2.84 | 1.3E-04 |

| 19320 | hexose catabolic process | 91 | 44.2 | 57.1 | 2.84 | 1.3E-04 |

| 8154 | actin polymerization and/or depolymerization | 54 | 46.3 | 75.9 | 2.83 | 8.3E-05 |

| 50658 | RNA transport | 47 | 48.5 | 70.2 | 2.81 | 1.8E-04 |

| 51236 | establishment of RNA localization | 47 | 48.5 | 70.2 | 2.81 | 1.8E-04 |

| 50657 | nucleic acid transport | 47 | 48.5 | 70.2 | 2.81 | 1.8E-04 |

| 32787 | monocarboxylic acid metabolic process | 225 | 35.8 | 84.4 | 2.81 | 1.3E-04 |

| 46907 | intracellular transport | 737 | 32 | 73.7 | 2.81 | 1.4E-04 |

| 6629 | lipid metabolic process | 650 | 32.2 | 78.3 | 2.80 | 1.5E-04 |

| 51170 | nuclear import | 80 | 42.6 | 76.2 | 2.79 | 8.2E-05 |

| 35023 | regulation of Rho protein signal transduction | 72 | 42.2 | 88.9 | 2.78 | 1.8E-04 |

| 42127 | regulation of cell proliferation | 425 | 34 | 67.1 | 2.78 | 9.4E-05 |

| 51028 | mRNA transport | 43 | 50 | 65.1 | 2.77 | 2.0E-04 |

| 48568 | embryonic organ development | 29 | 50 | 96.6 | 2.77 | 2.8E-05 |

| 44260 | cellular macromolecule metabolic process | 3301 | 29.1 | 74.1 | 2.77 | 1.3E-04 |

| 44267 | cellular protein metabolic process | 3258 | 29.1 | 74 | 2.77 | 1.3E-04 |

| 45454 | cell redox homeostasis | 58 | 44.7 | 81 | 2.77 | 8.9E-05 |

| 32501 | multicellular organismal process | 4035 | 29.2 | 52.9 | 2.76 | 1.1E-04 |

| 9218 | pyrimidine ribonucleotide metabolic process | 17 | 63.6 | 64.7 | 2.76 | 6.8E-05 |

| 1676 | long-chain fatty acid metabolic process | 16 | 63.6 | 68.8 | 2.76 | 3.0E-04 |

| 48628 | myoblast maturation | 29 | 55.6 | 62.1 | 2.75 | 5.1E-05 |

| 6913 | nucleocytoplasmic transport | 127 | 39.6 | 71.7 | 2.75 | 9.3E-05 |

| 7163 | establishment and/or maintenance of cell polarity | 33 | 52.2 | 69.7 | 2.75 | 1.5E-05 |

| 7369 | gastrulation | 51 | 43.4 | 103.9 | 2.73 | 6.4E-05 |

| 8203 | cholesterol metabolic process | 67 | 43.4 | 79.1 | 2.73 | 6.0E-05 |

| 51129 | negative regulation of cell organization and biogenesis | 34 | 48.4 | 91.2 | 2.71 | 9.3E-05 |

| 6606 | protein import into nucleus | 79 | 42.4 | 74.7 | 2.70 | 8.5E-05 |

| 48557 | embryonic digestive tract morphogenesis | 6 | 66.7 | 150 | 2.70 | 1.4E-06 |

| 48547 | gut morphogenesis | 9 | 66.7 | 100 | 2.70 | 1.0E-05 |

| 30510 | regulation of BMP signaling pathway | 13 | 66.7 | 69.2 | 2.70 | 1.6E-04 |

| 21915 | neural tube development | 37 | 45.2 | 113.5 | 2.70 | 6.9E-05 |

| 43549 | regulation of kinase activity | 193 | 37 | 69.9 | 2.69 | 1.2E-04 |

| 48699 | generation of neurons | 307 | 34.3 | 81.8 | 2.69 | 9.8E-05 |

| 16050 | vesicle organization and biogenesis | 9 | 80 | 55.6 | 2.68 | 2.2E-04 |

| 40016 | embryonic cleavage | 5 | 80 | 100 | 2.68 | 9.3E-05 |

| 8215 | spermine metabolic process | 6 | 80 | 83.3 | 2.68 | 6.2E-06 |

| 15012 | heparan sulfate proteoglycan biosynthetic process | 8 | 80 | 62.5 | 2.68 | 2.5E-04 |

| 46128 | purine ribonucleoside metabolic process | 6 | 80 | 83.3 | 2.68 | 7.4E-05 |

| 48488 | synaptic vesicle endocytosis | 11 | 80 | 45.5 | 2.68 | 1.5E-04 |

| 6400 | tRNA modification | 7 | 80 | 71.4 | 2.68 | 1.8E-04 |

| 30325 | adrenal gland development | 6 | 80 | 83.3 | 2.68 | 2.2E-04 |

| 7440 | foregut morphogenesis | 4 | 80 | 125 | 2.68 | 1.5E-05 |

| 1704 | formation of primary germ layer | 25 | 50 | 104 | 2.67 | 9.4E-05 |

| 16126 | sterol biosynthetic process | 31 | 50 | 83.9 | 2.67 | 7.4E-05 |

| 43406 | positive regulation of MAPK activity | 52 | 47.1 | 65.4 | 2.67 | 9.9E-05 |

| 47496 | vesicle transport along microtubule | 5 | 71.4 | 140 | 2.66 | 5.4E-05 |

| 9396 | folic acid and derivative biosynthetic process | 6 | 71.4 | 116.7 | 2.66 | 1.3E-04 |

| 30838 | positive regulation of actin filament polymerization | 7 | 71.4 | 100 | 2.66 | 2.0E-04 |

| 43525 | positive regulation of neuron apoptosis | 5 | 71.4 | 140 | 2.66 | 2.9E-04 |

| 7265 | Ras protein signal transduction | 172 | 37.4 | 71.5 | 2.66 | 1.7E-04 |

| 7409 | axonogenesis | 158 | 37.4 | 77.8 | 2.66 | 1.2E-04 |

| 50673 | epithelial cell proliferation | 23 | 52.4 | 91.3 | 2.65 | 8.4E-05 |

| 51338 | regulation of transferase activity | 198 | 36.7 | 70.2 | 2.64 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6007 | glucose catabolic process | 86 | 43.1 | 59.3 | 2.63 | 1.2E-04 |

| 22008 | neurogenesis | 330 | 33.8 | 82.4 | 2.63 | 1.1E-04 |

| 6461 | protein complex assembly | 203 | 36.8 | 65.5 | 2.62 | 1.3E-04 |

| 45859 | regulation of protein kinase activity | 186 | 36.9 | 69.9 | 2.61 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6631 | fatty acid metabolic process | 166 | 36.4 | 86.1 | 2.59 | 1.6E-04 |

| 1707 | mesoderm formation | 23 | 50 | 104.3 | 2.57 | 1.0E-04 |

| 96 | sulfur amino acid metabolic process | 21 | 57.1 | 66.7 | 2.56 | 1.1E-04 |

| 55001 | muscle cell development | 20 | 57.1 | 70 | 2.56 | 6.3E-05 |

| 6261 | DNA-dependent DNA replication | 73 | 43.5 | 63 | 2.55 | 1.2E-04 |

| 48667 | neuron morphogenesis during differentiation | 166 | 36.6 | 78.9 | 2.55 | 1.2E-04 |

| 48812 | neurite morphogenesis | 166 | 36.6 | 78.9 | 2.55 | 1.2E-04 |

| 1569 | patterning of blood vessels | 18 | 52.6 | 105.6 | 2.54 | 5.6E-05 |

| 51098 | regulation of binding | 23 | 52.6 | 82.6 | 2.54 | 1.8E-04 |

| 48627 | myoblast development | 30 | 52.6 | 63.3 | 2.54 | 5.1E-05 |

| 51052 | regulation of DNA metabolic process | 37 | 52.6 | 51.4 | 2.54 | 1.3E-04 |

| 8610 | lipid biosynthetic process | 256 | 34.7 | 78.9 | 2.53 | 1.1E-04 |

| 51726 | regulation of cell cycle | 461 | 33.5 | 60.3 | 2.52 | 1.3E-04 |

| 74 | regulation of progression through cell cycle | 459 | 33.5 | 59.9 | 2.51 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6082 | organic acid metabolic process | 521 | 32.2 | 79.3 | 2.51 | 1.3E-04 |

| 19752 | carboxylic acid metabolic process | 520 | 32.2 | 79.4 | 2.51 | 1.3E-04 |

| 8285 | negative regulation of cell proliferation | 189 | 37.3 | 58.2 | 2.48 | 9.9E-05 |

| 7417 | central nervous system development | 224 | 35.1 | 77.7 | 2.47 | 8.2E-05 |

| 16525 | negative regulation of angiogenesis | 15 | 58.3 | 80 | 2.47 | 1.2E-04 |

| 48565 | gut development | 15 | 58.3 | 80 | 2.47 | 8.9E-06 |

| 30833 | regulation of actin filament polymerization | 17 | 58.3 | 70.6 | 2.46 | 1.5E-04 |

| 40007 | growth | 252 | 34.5 | 78.2 | 2.46 | 9.9E-05 |

| 48519 | negative regulation of biological process | 1018 | 30.6 | 76.1 | 2.44 | 1.2E-04 |

| 10003 | gastrulation (sensu Mammalia) | 18 | 52.9 | 94.4 | 2.43 | 2.7E-05 |

| 46849 | bone remodeling | 99 | 38.4 | 86.9 | 2.43 | 1.4E-04 |

| 51216 | cartilage development | 37 | 45.5 | 89.2 | 2.42 | 9.3E-05 |

| 16331 | morphogenesis of embryonic epithelium | 52 | 41.5 | 101.9 | 2.42 | 7.3E-05 |

| 22607 | cellular component assembly | 536 | 32.6 | 61.8 | 2.41 | 1.4E-04 |

| 1503 | ossification | 89 | 39 | 86.5 | 2.41 | 1.5E-04 |

| 15980 | energy derivation by oxidation of organic compounds | 81 | 40.7 | 72.8 | 2.41 | 1.2E-04 |

| 2009 | morphogenesis of an epithelium | 106 | 37 | 101.9 | 2.41 | 1.1E-04 |

| 44272 | sulfur compound biosynthetic process | 35 | 48 | 71.4 | 2.39 | 1.6E-04 |

| 48523 | negative regulation of cellular process | 967 | 30.7 | 74.6 | 2.39 | 1.2E-04 |

| 31175 | neurite development | 192 | 35.3 | 79.7 | 2.38 | 1.1E-04 |

| 35088 | establishment and/or maintenance of apical/basal cell polarity | 12 | 60 | 83.3 | 2.37 | 2.5E-05 |

| 50818 | regulation of coagulation | 11 | 60 | 90.9 | 2.37 | 5.1E-05 |

| 8202 | steroid metabolic process | 145 | 36.5 | 79.3 | 2.36 | 9.8E-05 |

| 31214 | biomineral formation | 90 | 38.5 | 86.7 | 2.33 | 1.5E-04 |

| 31110 | regulation of microtubule polymerization or depolymerization | 14 | 53.3 | 107.1 | 2.32 | 1.2E-04 |

| 50678 | regulation of epithelial cell proliferation | 18 | 53.3 | 83.3 | 2.32 | 9.4E-05 |

| 8637 | apoptotic mitochondrial | 18 | 53.3 | 83.3 | 2.32 | 8.0E-05 |

| 17038 | protein import | 93 | 39.1 | 74.2 | 2.31 | 1.0E-04 |

| 51270 | regulation of cell motility | 67 | 40.4 | 85.1 | 2.31 | 6.3E-05 |

| 44275 | cellular carbohydrate catabolic process | 110 | 39.7 | 57.3 | 2.31 | 1.3E-04 |

| 48469 | cell maturation | 83 | 40 | 72.3 | 2.31 | 4.6E-05 |

| 14031 | mesenchymal cell development | 28 | 45.2 | 110.7 | 2.31 | 4.7E-05 |

| 6241 | CTP biosynthetic process | 13 | 62.5 | 61.5 | 2.28 | 6.6E-06 |

| 9209 | pyrimidine ribonucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 13 | 62.5 | 61.5 | 2.28 | 6.6E-06 |

| 6098 | pentose-phosphate shunt | 9 | 62.5 | 88.9 | 2.28 | 2.4E-04 |

| 97 | sulfur amino acid biosynthetic process | 12 | 62.5 | 66.7 | 2.28 | 9.6E-05 |

| 1836 | release of cytochrome c from mitochondria | 10 | 62.5 | 80 | 2.28 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6465 | signal peptide processing | 8 | 62.5 | 100 | 2.28 | 3.1E-06 |

| 6740 | NADPH regeneration | 9 | 62.5 | 88.9 | 2.28 | 2.4E-04 |

| 10165 | response to X-ray | 5 | 62.5 | 160 | 2.28 | 2.1E-04 |

| 43648 | dicarboxylic acid metabolic process | 12 | 62.5 | 66.7 | 2.28 | 1.4E-04 |

| 50920 | regulation of chemotaxis | 10 | 62.5 | 80 | 2.28 | 1.8E-04 |

| 50921 | positive regulation of chemotaxis | 9 | 62.5 | 88.9 | 2.28 | 1.8E-04 |

| 1837 | epithelial to mesenchymal transition | 6 | 62.5 | 133.3 | 2.28 | 3.7E-05 |

| 9208 | pyrimidine ribonucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 13 | 62.5 | 61.5 | 2.28 | 6.6E-06 |

| 46036 | CTP metabolic process | 13 | 62.5 | 61.5 | 2.28 | 6.6E-06 |

| 51347 | positive regulation of transferase activity | 118 | 37.5 | 74.6 | 2.27 | 1.2E-04 |

| 1839 | neural plate morphogenesis | 35 | 43.2 | 105.7 | 2.26 | 9.1E-05 |

| 7420 | brain development | 152 | 35.3 | 89.5 | 2.24 | 8.8E-05 |

| 6066 | alcohol metabolic process | 300 | 33.5 | 72.7 | 2.24 | 1.0E-04 |

| 16049 | cell growth | 139 | 36.6 | 72.7 | 2.23 | 6.3E-05 |

| 6096 | glycolysis | 76 | 41.9 | 56.6 | 2.23 | 9.1E-05 |

| 7498 | mesoderm development | 51 | 41.9 | 84.3 | 2.23 | 6.8E-05 |

| 75 | cell cycle checkpoint | 47 | 46.2 | 55.3 | 2.23 | 1.2E-04 |

| 45333 | cellular respiration | 36 | 46.2 | 72.2 | 2.23 | 1.4E-04 |

| 51168 | nuclear export | 40 | 46.2 | 65 | 2.23 | 1.0E-04 |

| 1843 | neural tube closure | 22 | 46.2 | 118.2 | 2.23 | 1.0E-04 |

| 16337 | cell-cell adhesion | 250 | 34.6 | 63.6 | 2.23 | 6.4E-05 |

| 30182 | neuron differentiation | 273 | 33.5 | 78.8 | 2.22 | 1.1E-04 |

| 48562 | embryonic organ morphogenesis | 15 | 50 | 120 | 2.22 | 1.6E-06 |

| 30334 | regulation of cell migration | 58 | 40.8 | 84.5 | 2.22 | 7.2E-05 |

| 65009 | regulation of a molecular function | 365 | 32.8 | 71.8 | 2.22 | 1.5E-04 |

| 40012 | regulation of locomotion | 70 | 39.3 | 87.1 | 2.21 | 6.9E-05 |

| 42541 | hemoglobin biosynthetic process | 4 | 66.7 | 150 | 2.20 | 2.5E-04 |

| 20027 | hemoglobin metabolic process | 4 | 66.7 | 150 | 2.20 | 2.5E-04 |

| 6108 | malate metabolic process | 6 | 66.7 | 100 | 2.20 | 1.7E-04 |

| 48558 | embryonic gut morphogenesis | 5 | 66.7 | 120 | 2.20 | 2.1E-06 |

| 8156 | negative regulation of DNA replication | 12 | 66.7 | 50 | 2.20 | 2.5E-04 |

| 7028 | cytoplasm organization and biogenesis | 23 | 53.8 | 56.5 | 2.20 | 1.4E-04 |

| 15698 | inorganic anion transport | 153 | 36 | 72.5 | 2.20 | 1.6E-04 |

| 30239 | myofibril assembly | 19 | 53.8 | 68.4 | 2.20 | 5.1E-05 |

| 31111 | negative regulation of microtubule polymerization or depolymerization | 12 | 53.8 | 108.3 | 2.20 | 1.4E-04 |

| 55002 | striated muscle cell development | 19 | 53.8 | 68.4 | 2.20 | 5.1E-05 |

| 9165 | nucleotide biosynthetic process | 149 | 36.1 | 72.5 | 2.19 | 1.3E-04 |

| 2027 | cardiac chronotropy | 2 | 75 | 200 | 2.18 | 4.1E-05 |

| 9966 | regulation of signal transduction | 411 | 32.1 | 78.8 | 2.17 | 1.6E-04 |

| 40008 | regulation of growth | 169 | 35.1 | 79.3 | 2.17 | 1.0E-04 |

| 48762 | mesenchymal cell differentiation | 29 | 43.8 | 110.3 | 2.16 | 4.7E-05 |

| 187 | activation of MAPK activity | 48 | 43.8 | 66.7 | 2.16 | 9.9E-05 |

| 51246 | regulation of protein metabolic process | 276 | 33.3 | 77.2 | 2.16 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6284 | base-excision repair | 24 | 47.6 | 87.5 | 2.15 | 1.0E-04 |

| 7281 | germ cell development | 34 | 47.6 | 61.8 | 2.15 | 1.9E-05 |

| 8645 | hexose transport | 30 | 47.6 | 70 | 2.15 | 2.6E-04 |

| 15749 | monosaccharide transport | 30 | 47.6 | 70 | 2.15 | 2.6E-04 |

| 9952 | anterior/posterior pattern formation | 83 | 37.7 | 92.8 | 2.15 | 1.1E-04 |

| 30041 | actin filament polymerization | 28 | 47.6 | 75 | 2.15 | 1.2E-04 |

| 30282 | bone mineralization | 26 | 47.6 | 80.8 | 2.15 | 1.8E-04 |

| 16477 | cell migration | 285 | 33 | 80.7 | 2.15 | 9.0E-05 |

| 21700 | developmental maturation | 99 | 37.8 | 74.7 | 2.15 | 6.9E-05 |

| 43623 | cellular protein complex assembly | 48 | 42.9 | 72.9 | 2.14 | 1.1E-04 |

| 6259 | DNA metabolic process | 733 | 31 | 68.8 | 2.13 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6357 | regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 431 | 32.1 | 70.8 | 2.12 | 1.1E-04 |

| 31589 | cell-substrate adhesion | 74 | 38.7 | 83.8 | 2.12 | 6.1E-05 |

| 7219 | Notch signaling pathway | 51 | 40.9 | 86.3 | 2.11 | 5.6E-05 |

| 40029 | regulation of gene expression\, epigenetic | 64 | 40.9 | 68.8 | 2.11 | 1.9E-04 |

| 48666 | neuron development | 213 | 33.9 | 80.3 | 2.11 | 1.2E-04 |

| 8361 | regulation of cell size | 142 | 35.8 | 74.6 | 2.11 | 6.2E-05 |

| 9798 | axis specification | 17 | 50 | 94.1 | 2.09 | 1.4E-04 |

| 31570 | DNA integrity checkpoint | 26 | 50 | 61.5 | 2.09 | 4.0E-06 |

| 31109 | microtubule polymerization or depolymerization | 15 | 50 | 106.7 | 2.09 | 1.2E-04 |

| 45860 | positive regulation of protein kinase activity | 110 | 37 | 73.6 | 2.08 | 1.3E-04 |

| 7026 | negative regulation of microtubule depolymerization | 10 | 54.5 | 110 | 2.08 | 1.6E-04 |

| 7019 | microtubule depolymerization | 11 | 54.5 | 100 | 2.08 | 1.6E-04 |

| 31114 | regulation of microtubule depolymerization | 10 | 54.5 | 110 | 2.08 | 1.6E-04 |

| 9117 | nucleotide metabolic process | 229 | 34 | 70.7 | 2.06 | 1.3E-04 |

| 48771 | tissue remodeling | 105 | 36.2 | 89.5 | 2.05 | 1.6E-04 |

| 16052 | carbohydrate catabolic process | 115 | 37.9 | 57.4 | 2.03 | 1.3E-04 |

| 6220 | pyrimidine nucleotide metabolic process | 41 | 45.5 | 53.7 | 1.97 | 9.7E-05 |

| 271 | polysaccharide biosynthetic process | 24 | 45.5 | 91.7 | 1.97 | 1.4E-04 |

| 6793 | phosphorus metabolic process | 912 | 29.9 | 76.6 | 1.89 | 1.2E-04 |

| 6796 | phosphate metabolic process | 912 | 29.9 | 76.6 | 1.89 | 0.0001225 |

Highlights.

Quantitative pathway analysis of gene expression through time in testis development concisely summarizes pathway dynamics across development

The result of this analysis successfully captures and quantifies key processes of male reproductive development described in the literature

This approach provides a framework for quantifying perturbation of normal developmental dynamics by environmental factors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carlsen E, Giwercman A, Keiding N, Skakkebaek NE. Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during past 50 years. BMJ. 1992;305(6854):609–613. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6854.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swan SH, Elkin EP, Fenster L. Have sperm densities declined? A reanalysis of global trend data. Environmental health perspectives. 1997;105(11):1228–1232. doi: 10.1289/ehp.971051228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolland M, Le Moal J, Wagner V, Royere D, De Mouzon J. Decline in semen concentration and morphology in a sample of 26,609 men close to general population between 1989 and 2005 in France. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(2):462–470. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen AG, Jensen TK, Carlsen E, Jorgensen N, Andersson AM, Krarup T, et al. High frequency of sub-optimal semen quality in an unselected population of young men. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(2):366–372. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen TK, Carlsen E, Jorgensen N, Berthelsen JG, Keiding N, Christensen K, et al. Poor semen quality may contribute to recent decline in fertility rates. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(6):1437–1440. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Main KM. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: an increasingly common developmental disorder with environmental aspects. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(5):972–978. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharpe RM, Skakkebaek NE. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: mechanistic insights and potential new downstream effects. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2 Suppl):e33–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berruti G. Signaling events during male germ cell differentiation: bases and perspectives. Front Biosci. 1998;3:D1097–D1108. doi: 10.2741/a347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Western P. Foetal germ cells: striking the balance between pluripotency and differentiation. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53(2–3):393–409. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082671pw. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray LE, Jr, Ostby J, Furr J, Price M, Veeramachaneni DN, Parks L. Perinatal exposure to the phthalates DEHP, BBP, and DINP, but not DEP, DMP, or DOTP, alters sexual differentiation of the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58(2):350–365. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parks LG, Ostby JS, Lambright CR, Abbott BD, Klinefelter GR, Barlow NJ, et al. The plasticizer diethylhexyl phthalate induces malformations by decreasing fetal testosterone synthesis during sexual differentiation in the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58(2):339–349. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The National Academies Press; 2000. NRC, Scientific Frontiers in Developmental Toxicology and Risk Assessment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marjani SL, Le Bourhis D, Vignon X, Heyman Y, Everts RE, Rodriguez-Zas SL, et al. Embryonic gene expression profiling using microarray analysis. Reproduction, fertility, and development. 2009;21(1):22–30. doi: 10.1071/rd08217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armit C. Developmental biology and databases: how to archive, find and query gene expression patterns using the world wide web. Organogenesis. 2007;3(2):70–73. doi: 10.4161/org.3.2.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escalier D. Impact of genetic engineering on the understanding of spermatogenesis. Human reproduction update. 2001;7(2):191–210. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verhoeven G, Willems A, Denolet E, Swinnen JV, De Gendt K. Androgens and spermatogenesis: lessons from transgenic mouse models. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1546):1537–1556. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Small CL, Shima JE, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK, Griswold MD. Profiling gene expression during the differentiation and development of the murine embryonic gonad. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(2):492–501. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.033696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shima JE, McLean DJ, McCarrey JR, Griswold MD. The murine testicular transcriptome: characterizing gene expression in the testis during the progression of spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(1):319–330. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.026880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemente EJ, Furlong RA, Loveland KL, Affara NA. Gene expression study in the juvenile mouse testis: identification of stage-specific molecular pathways during spermatogenesis. Mamm Genome. 2006;17(9):956–975. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouma GJ, Hudson QJ, Washburn LL, Eicher EM. New candidate genes identified for controlling mouse gonadal sex determination and the early stages of granulosa and Sertoli cell differentiation. Biol Reprod. 2010;82(2):380–389. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houmard B, Small C, Yang L, Naluai-Cecchini T, Cheng E, Hassold T, et al. Global gene expression in the human fetal testis and ovary. Biol Reprod. 2009;81(2):438–443. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doniger SW, Salomonis N, Dahlquist KD, Vranizan K, Lawlor SC, Conklin BR. MAPPFinder: using Gene Ontology and GenMAPP to create a global gene-expression profile from microarray data. Genome Biol. 2003;4(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4(5):P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beissbarth T, Speed TP. GOstat: find statistically overrepresented Gene Ontologies within a group of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1464–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Shahrour F, Diaz-Uriarte R, Dopazo J. FatiGO: a web tool for finding significant associations of Gene Ontology terms with groups of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(4):578–580. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laiho A, Kotaja N, Gyenesei A, Sironen A. Transcriptome profiling of the murine testis during the first wave of spermatogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu X, Griffith WC, Hanspers K, Dillman JF, 3rd, Ong H, Vredevoogd MA, et al. A system-based approach to interpret dose- and time-dependent microarray data: quantitative integration of gene ontology analysis for risk assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2006;92(2):560–577. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillman JF, 3rd, Phillips CS, Dorsch LM, Croxton MD, Hege AI, Sylvester AJ, et al. Genomic analysis of rodent pulmonary tissue following bis-(2-chloroethyl) sulfide exposure. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18(1):28–34. doi: 10.1021/tx049745z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]