Abstract

There are limited data to guide the choice of high-dose therapy (HDT) regimen prior to autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) for patients with Hodgkin (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). We studied 4,917 patients (NHL n=3,905; HL n=1,012) who underwent AHCT from 1995-2008 using the most common HDT platforms: BEAM (n=1730), CBV (n=1853), BuCy (n=789), and TBI-containing (n=545). CBV was divided into CBVhigh and CBVlow based on BCNU dose. We analyzed the impact of regimen on development of idiopathic pulmonary syndrome (IPS), transplant-related mortality (TRM), progression free and overall survival (PFS and OS). The 1-year incidence of IPS was 3-6% and was highest in recipients of CBVhigh (HR 1.9) and TBI (HR 2.0) compared to BEAM. 1-year TRM was 4-8% and was similar between regimens. Among patients with NHL, there was a significant interaction between histology, HDT regimen, and outcome. Compared to BEAM, CBVlow (HR 0.63) was associated with lower mortality in follicular lymphoma (p<0.001), and CBVhigh (HR1.44) with higher mortality in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (p=0.001). For patients with HL, CBVhigh (HR1.54), CBVlow (HR1.53), BuCy (HR1.77) and TBI (HR 3.39) were associated with higher mortality compared to BEAM (p<0.001). The impact of specific AHCT regimen on post transplant survival is different depending on histology; therefore, further studies are required to define the best regimen for specific diseases.

Keywords: autologous transplant, lymphoma, idiopathic pneumonia syndrome

Introduction

High-dose therapy (HDT) with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) has been a standard component of therapy for patients with Hodgkin1 and non-Hodgkin lymphoma2,3 for decades. The therapeutic rationale of HDT with AHCT relies on enhanced cytotoxicity through the delivery of myeloablative doses of chemotherapy or total body irradiation. The choice of HDT regimen has traditionally been based on institutional experience, and several regimens are considered standard and routinely used for patients with all histologies of lymphoma.4

Each HDT regimen is associated with its own unique toxicities, based on the individual agents or modalities used. One example is idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS), which encompasses non-infectious pneumonitides caused by high dose alkylating chemotherapy (e.g., BCNU) or total body irradiation (TBI) and is the major pulmonary toxicity after HDT.5 As prompt initiation of corticosteroids can often result in clinical improvement, early recognition of IPS is important, and the published risk factors for IPS after AHCT are variable.6-12

A large study of lymphoma patients undergoing AHCT in the modern era has not been performed to define the impact of conditioning regimens on overall outcomes, or to describe the incidence and risk factors for developing IPS and its impact on outcomes. To this end, we undertook a large retrospective registry study to analyze the impact of several commonly used HDT regimens on clinical outcomes.

Methods

Data Source

The CIBMTR includes a voluntary working group of more than 450 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on consecutive allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantations to a statistical center at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) Coordinating Center in Minneapolis. Participating centers are required to report all transplants consecutively; patients are followed longitudinally and compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in CIBMTR's capacity as a Public Health Authority under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.13

Patient Selection

All adult patients (≥18 years) reported to the CIBMTR who received AHCT using marrow or peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) for NHL or HL between 1995 and 2008 were included in this analysis. Patients were excluded for: no post-transplant follow up information (n=138), BCNU given in a regimen other than BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) 14 or CBV (cyclophosphamide, BCNU, etoposide [VP-16]) 15 (n=145), or date of development of IPS was prior to the transplant (n=23). Among recipients of BEAM, cases were excluded if the BCNU dose per body surface area was less than 10th percentile (n=228), greater than the 90th percentile (n=4) or if the dose was missing (n=166). Among recipients of CBV, patients were excluded if the BCNU dose per body surface area was less than 10th percentile (n=137) or if the dose was missing (n=241). Among patients who received non-BCNU regimens, only patients who received BuCy (busulfan, cyclophosphamide16 and TBI (total body irradiation) 17 were included to the final dataset. A total of 4,917 patients were identified from 204 centers. In order to address the impact of BCNU dose on outcomes, the total dose administered of BCNU was divided by the calculated body surface area from height and weight data reported to the CIBMTR. According to patterns of practice, the dose distribution of BCNU varied widely among recipients of CBV, clustering approximately around 300 mg/m2 (median 296 mg/m2, range 225-374 mg/m2)and at 450mg/m2(median 453 mg/m2, range 376-807 mg/m2), which were then separated into CBVlow and CBVhigh, respectively. Among recipients of BEAM, the BCNU dose distribution was approximately around 300mg/m2 (median 293 mg/m2, range 227-347 mg/m2).

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this analysis was overall survival (OS) among the different conditioning regimens. Secondary endpoints included IPS, transplant-related mortality (TRM), relapse or progression, and progression-free survival (PFS). TRM was defined as any death without recurrent lymphoma. Relapse or progression was defined as evidence of disease recurrence censored at the date of last contact and using death in remission as the competing hazard. PFS was defined as survival without death or relapse censored at the date of last contact.

Statistical Analysis

Patient-, disease- and transplant-related characteristics were described according to each conditioning regimen and compared using chi-square tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate. The cumulative incidence function was used for calculating IPS, TRM, relapse or progression outcomes accounting for competing risks. OS and PFS were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariable analysis for each outcome was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. The effect of development of IPS on subsequent TRM, treatment failure (relapse progression or death) and overall mortality was performed by fitting a Cox model with a time-dependent effect for prior development of IPS. Preparative regimens were included in all models as the main effect. The proportional hazards assumption was checked using graphical approaches or time-dependent covariates. Stepwise model building was used to identify additional predictors besides preparative regimen, from among the following candidate variables included: age (18-39, 40-49, 50-59, ≥60), gender, body mass index (<18.5, 18.5-25, 25-30, > 30, unknown), Karnofsky performance status (<90, 90-100, unknown), disease status at AutoHCT, number of prior chemotherapy regimens received, year of AutoHCT (1995-1999, 2000-2004, 2005-2008), history of smoking, time from diagnosis to AutoHCT, prior use of rituximab in NHL patients and graft type (bone marrow vs. peripheral blood stem cells). Interactions between preparative regimen and other baseline characteristics were checked. Disease was tested in two ways, first separating on Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and second separating NHL according to histologies. Both ways demonstrated a significant interaction between disease and conditioning on several outcomes. Details of the final model are shown for the four largest disease groupings: HL, follicular lymphoma (FL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Considering multiple comparisons across conditioning regimens, only p-values≤0.01 were considered significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Patient characteristics for each regimen are summarized in Table 1. The cohorts differed in age, distribution of disease, year of AHCT, Karnofsky performance score (KPS), prior chemotherapy, time from diagnosis to AHCT and prior use of rituximab in NHL patients. Recipients of AHCT with BEAM were older: age ≥ 54 years (BEAM 53%, CBVlow 38%, CBVhigh 34%, BuCy 50% and TBI 40%, p<0.001). A lower proportion of BEAM and TBI patients had Hodgkin lymphoma: (BEAM 18%, CBVlow 23%, CBVhigh 37%, BuCy 21% and TBI 4%, p<0.001). BEAM was used more frequently in later years of the study period: year of AHCT 2002 or later: (BEAM 70%, CBVlow 18%, CBVhigh 26%, BuCy 49% and TBI 19%, p<0.001). For patients with NHL, prior rituximab use was different: (BEAM 67%, CBVlow 18%, CBVhigh 29%, BuCy 43% and TBI 21%, p<0.001). Among patients with available age adjusted IPI, the proportion of patients with low and low-intermediate IPI was in the range of 82% to 88% across the conditioning groups. The cohorts were similar in terms of gender and median follow-up for survivors.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | BEAM | CBVlow | CBVhigh | BuCy | TBI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1730 | 1249 | 604 | 789 | 545 | -- |

| Number of centers | 126 | 106 | 92 | 54 | 68 | -- |

| Age | ||||||

| Median (range) | 55 (18-79) | 49 (18-80) | 46 (18-74) | 54 (18-76) | 51 (19-73) | <0.001 |

| Age < 54, (%) | 819 (47) | 775 (62) | 396 (66) | 392 (50) | 327 (60) | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.57 | |||||

| Male (%) | 1108 (64) | 787 (63) | 368 (61) | 499 (63) | 332 (60) | |

| Female (%) | 622 (36) | 462 (37) | 236 (39) | 290 (37) | 213 (40) | |

| Karnofsky Score | <0.001 | |||||

| < 90 (%) | 545 (32) | 413 (33) | 133 (22) | 253 (32) | 145 (27) | |

| 90-100 (%) | 1089 (63) | 809 (65) | 456 (75) | 501 (63) | 386 (71) | |

| Missing (%) | 96 (6) | 27 (2) | 15 (2) | 35 (4) | 14 (3) | |

| Disease | <0.001 | |||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 316 (18) | 283 (23) | 224 (37) | 165 (21) | 24 (4) | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1414 (82) | 966 (77) | 380 (63) | 624 (79) | 521 (96) | |

| Follicular | 254 (15) | 171 (14) | 60 (10) | 126 (16) | 152 (28) | |

| Diffuse large cell | 735 (42) | 472 (38) | 190 (31) | 279 (35) | 161 (30) | |

| Lymphoblastic | 64 (4) | 34 (3) | 18 (3) | 26 (3) | 24 (4) | |

| Burkitt's / Burkitt's like | 19 (1) | 29 (2) | 13 (2) | 9 (1) | 14 (3) | |

| Mantle cell | 162 (9) | 96 (8) | 47 (8) | 77 (10) | 91 (17) | |

| Other | 180 (10) | 164 (13) | 52 (9) | 107 (14) | 79 (14) | |

| Disease status at AHCT | <0.001 | |||||

| PIF sensitive | 304 (18) | 218 (17) | 109 (18) | 142 (18) | 90 (17) | |

| PIF resistant | 58 (3) | 45 (4) | 30 (5) | 36 (5) | 28 (5) | |

| CR1 | 336 (19) | 254 (20) | 95 (16) | 115 (15) | 115 (21) | |

| REL sensitive | 422 (24) | 355 (28) | 166 (27) | 213 (27) | 112 (21) | |

| REL resistant | 104 (6) | 70 (6) | 45 (7) | 49 (6) | 35 (6) | |

| CR2+ | 430 (25) | 217 (17) | 104 (17) | 149 (19) | 70 (13) | |

| REL/PIF untreated/unknown | 22 (1) | 39 (3) | 28 (5) | 12 (2) | 13 (2) | |

| Missing | 54 (3) | 51 (4) | 27 (4) | 73 (9) | 82 (15) | |

| Age adjusted IPI score | <0.001 | |||||

| Low | 415 (24) | 398 (32) | 147 (24) | 172 (22) | 159 (29) | |

| Low-Intermediate | 386 (22) | 328 (26) | 171 (28) | 195 (25) | 150 (28) | |

| High-Intermediate | 98 (6) | 98 (8) | 66 (11) | 68 (9) | 54 (10) | |

| High | 12 (<1) | 8 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 8 (1) | 4 (<1) | |

| Undetermined | 819 (47) | 417 (33) | 219 (36) | 346 (44) | 178 (33) | |

| Number of regimens of Chemotherapy received | <0.001 | |||||

| 1-2 | 953 (55) | 770 (62) | 346 (57) | 404 (51) | 285 (52) | |

| ≥ 3 | 769 (44) | 469 (38) | 250 (42) | 379 (48) | 251 (46) | |

| Use of rituximab in NHL | <0.001 | |||||

| Rituximab | 949 (67) | 177 (18) | 110 (29) | 266 (43) | 109 (21) | |

| No rituximab | 465 (33) | 789 (82) | 270 (71) | 358 (57) | 412 (79) | |

| Year of ASCT | <0.001 | |||||

| 1995-1999 | 302 (17) | 865 (69) | 393 (65) | 296 (37) | 400 (74) | |

| 2000-2004 | 446 (26) | 288 (23) | 104 (17) | 218 (27) | 74 (14) | |

| 2005-2008 | 982 (57) | 96 (7) | 107 (17) | 277 (35) | 71 (13) | |

| Time from dx to AHCT, median (range), months | 17 (2-383) | 16 (3-259) | 16 (3-362) | 17 (3-282) | 14 (3-272) | 0.017 |

| Graft type | <0.001 | |||||

| Bone marrow (%) | 15 (<1) | 84 (7) | 36 (6) | 48 (6) | 79 (14) | |

| Peripheral blood (%) | 1715 (99) | 1165 (93) | 568 (94) | 741 (94) | 466 (86) | |

| Dose of BCNU, median (range), mg/m2 | 293 (227 – 347) | 296 (225 – 374) | 453 (376 – 807) | -- | -- | - |

| History of smoking | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 764 (44) | 491 (39) | 257 (43) | 347 (44) | 242 (44) | |

| No | 911 (53) | 658 (53) | 305 (50) | 401 (51) | 264 (48) | |

| Missing | 55 (3) | 100 (8) | 42 (7) | 41 (5) | 39 (7) | |

| Median follow-up, median range), months | 66 (1-193) | 116 (1-217) | 110 (1-216) | 72 (1-194) | 95 (3-206) |

Abbreviations: BEAM = BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; CBV = cyclophosphamide, BCNU, etoposide; BuCy = busulfan, cyclophosphamide; TBI = total body irradiation; AHCT = autologous hematopoietic cell; transplantation; PIF = primary induction failure; REL = relapsed; CR = complete remission; NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Idiopathic Pneumonia Syndrome

The incidence of IPS by 1 year after AHCT was: BEAM (3% [2-4%]), CBVlow (3% [2-4%]), CBVhigh (6% [4-8%]), BuCy (4% [2-5%]), and TBI (5% [3-7%]). Multivariate analysis showed that in comparison to BEAM, the risk of IPS for each regimen was: CBVlow (HR 1.07 [0.72-1.60], p=0.742), CBVhigh (HR 1.88 [1.24-2.83], p=0.003), BuCy (HR 1.25 [0.82-1.92], p=0.30), and TBI (HR 2.03 [1.30-3.19], p=0.002) (Table 2). Additional risk factors associated with the development of IPS: 1) diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma (HR 2.33, [1.68-3.24], p < 0.001), 2) female gender (HR 1.39 [1.05-1.82], p=0.019), 3) chemotherapy-resistant disease at time of AHCT (HR 1.9 [1.29-2.79], p=0.001), and 4) age ≥ 55 (HR 1.54, [1.13-2.09], p=0.006). In the entire cohort, patients who developed IPS had a significantly higher rate of TRM (HR 4.02, [3.09-5.24], p < 0.001), shorter PFS (HR 1.85, [1.53-2.24], p < 0.001), and shorter OS (HR 2.50, [2.10-2.99], p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis for IPS

| Regimen | Reference | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBVlow | BEAM | 1.07 (0.72-1.6) | 0.742 |

| CBVhigh | BEAM | 1.88 (1.24-2.83) | 0.003 |

| BuCy | BEAM | 1.25 (0.82-1.92) | 0.299 |

| TBI | BEAM | 2.03 (1.30-3.19) | 0.002 |

| CBVhigh | CBVlow | 1.75 (1.14-2.70) | 0.01 |

| BuCy | CBVlow | 1.17 (0.75-1.84) | 0.489 |

| TBI | CBVlow | 1.90 (1.19-3.04) | 0.008 |

| BuCy | CBVhigh | 0.67 (0.42-1.06) | 0.085 |

| TBI | CBVhigh | 1.08 (0.67-1.76) | 0.746 |

| TBI | BuCy | 1.62 (0.99-2.65) | 0.055 |

Transplant Related Mortality

There was no difference in TRM for patients with HL compared to those with NHL, and thus, the groups were combined for analysis. The incidence of TRM at 1 year for each cohort was as follows: BEAM (4% [3-5%]), CBVlow (7% [5-8%]), CBVhigh (8% [6-11%]), BuCy (7% [6-9%]), and TBI (8% [6-10%]) and was not significantly different after multivariate analysis. While choice of high-dose regimen had no effect on TRM, the following factors were associated with increased TRM: older age, male gender, KPS < 90, chemo-resistant disease, higher number of previously received chemotherapy regimens, earlier year of AHCT, history of smoking, and use of bone marrow as source of progenitor cells (data not shown).

Relapse / Progression

The cumulative incidences of disease progression or relapse varied according to histologies and are shown in Table 3. Multivariate analysis of disease progression or relapse (Table 4) demonstrated that the effect of conditioning on outcome was significant for patients with MCL and HL. Among patients with MCL, the HR for disease progression or relapse for CBVlow was 0.55 (95% CI 0.34-0.88, p=0.014) compared to BEAM. Conversely, when testing all possible comparisons, the HR for CBVhigh and TBI were 2.28 (95% CI, 1.29-4.04, p<0.005) and 2.28 (95% CI. 1.38-3.76, p=0.001) compared to CBVlow, respectively (Table 4). For patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, BuCy (HR 1.52 [1.13-2.05] compared to BEAM, p=0.006) and CyTBI (HR 1.94, [1.09-3.45] compared to BEAM, p=0.024) were associated with higher rates of progression compared to BEAM, CBVlow and CBVhigh. Multivariate analysis also showed the following factors to be associated with increased relapse or disease progression: older age, chemo-resistant disease, higher number of prior regimens of chemotherapy, and shorter time from diagnosis to AHCT (data not shown).

Table 3.

Univariate probabilities for treatment related mortality, disease progression or relapse, progression free survival and overall survival across different high dose regimens prior to autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma.

| Outcomes | BEAM (95% CI) | CBVlow (95% CI) | CBVhigh (95% CI) | BuCy (95% CI) | TBI (95% CI) | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | ||||||

| Progression/Relapse | ||||||

| Number of patients | 313 | 279 | 219 | 162 | 23 | |

| @ 3 years | 32 (27-37) | 32 (26-38) | 30 (24-36) | 41 (34-49) | 57 (37-76) | 0.026 |

| Progression-free survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 313 | 279 | 219 | 162 | 23 | 0.004 |

| @ 3 years | 62 (56-67) | 60 (54-66) | 57 (50-64) | 51 (43-59) | 43 (24-63) | 0.110 |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 316 | 283 | 224 | 165 | 24 | <0.001 |

| @ 3 years | 79 (74-83) | 73 (68-79) | 68 (61-74) | 65 (58-73) | 47 (27-68) | 0.001 |

| Follicular Lymphoma | ||||||

| Progression/Relapse | ||||||

| Number of patients | 253 | 171 | 60 | 125 | 151 | |

| @ 3 years | 39 (33-46) | 28 (21-35) | 51 (38-63) | 31 (23-39) | 39 (31-47) | 0.010 |

| Progression free survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 253 | 171 | 60 | 125 | 151 | |

| @ 3 years | 52 (45-58) | 67 (59-74) | 41 (28-54) | 60 (52-69) | 54 (45-62) | 0.002 |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 254 | 171 | 60 | 126 | 152 | |

| @ 3 years | 73 (68-79) | 81 (75-87) | 55 (42-68) | 79 (71-86) | 71 (63-78) | 0.004 |

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma | ||||||

| Progression/Relapse | ||||||

| Number of patients | 731 | 465 | 187 | 273 | 156 | |

| @ 3 years | 44 (40-47) | 40 (36-45) | 47 (40-54) | 41 (35-47) | 42 (35-50) | 0.599 |

| Progression free survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 731 | 465 | 187 | 273 | 156 | |

| @ 3 years | 47 (44-51) | 47 (43-52) | 39 (32-46) | 45 (39-52) | 42 (34-50) | 0.273 |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 735 | 472 | 190 | 279 | 161 | |

| @ 3 years | 58 (55-62) | 55 (50-59) | 43 (36-51) | 52 (46-58) | 47 (40-55) | 0.002 |

| Mantle Cell Lymphoma | ||||||

| Progression relapse | ||||||

| Number of patients | 162 | 96 | 47 | 77 | 90 | |

| @ 3 years | 27 (21-35) | 22 (14-32) | 44 (30-59) | 44 (33-55) | 24 (16-34) | 0.006 |

| Progression free survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 162 | 96 | 47 | 77 | 90 | 0.611 |

| @ 3 years | 62 (54-70) | 57 (47-68) | 49 (35-64) | 47 (36-58) | 62 (51-72) | 0.165 |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Number of patients | 162 | 96 | 47 | 77 | 91 | 0.127 |

| @ 3 years | 75 (68-82) | 66 (56-76) | 80 (68-90) | 60 (49-71) | 66 (56-76) | 0.051 |

Table 4.

Impact of high-dose therapy regimen on treatment related mortality, disease progression or relapse, treatment failure (death or disease progression) and overall mortality by each histology.

| Regimen | Disease Progression/Relapse (95% CI) | p | Treatment Failure HR (95% CI) | p | Overall Mortality HR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL | |||||||

| BEAM | 1.00 | 0.008*1 | 1.00 | <0.001*1 | 1.00 | <0.001*1 | |

| CBVlow | 1.12 (0.85-1.47) | 0.41 | 1.27 (1.01-1.61) | 0.04 | 1.53 (1.16-2.02) | 0.003 | |

| CBVhigh | 0.95 (0.71-1.28) | 0.75 | 1.18 (0.92-1.51) | 0.20 | 1.54 (1.15-2.05) | 0.003 | |

| BuCy | 1.52 (1.13-2.05) | 0.0061 | 1.51 (1.15-1.97) | 0.0031 | 1.77 (1.30-2.42) | <0.0011 | |

| TBI | 1.94 (1.09-3.46) | 0.024 | 2.01 (1.21-3.34) | 0.0071 | 3.38 (2.03-5.63) | <0.0011 | |

| CBVhigh vs. CBVlow | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | 0.30 | 0.92 (0.73-1.18) | 0.53 | 1.00 (0.77-1.30) | 0.97 | |

| BuCy vs CBVlow | 1.35 (1.00-1.84) | 0.05 | 1.19 (0.91-1.55) | 0.21 | 1.16 (0.86-1.55) | 0.32 | |

| TBI vs. CBVlow | 1.73 (0.97-3.09) | 0.06 | 1.58 (0.95-2.62) | 0.07 | 2.20 (1.34-3.63) | 0.0021 | |

| BuCy vs. CBVhigh | 1.59 (1.15-2.21) | 0.0061 | 1.28 (0.97-1.70) | 0.08 | 1.16 (0.85-1.56) | 0.35 | |

| TBI vs. CBVhigh | 2.04 (1.13-3.69) | 0.02 | 1.71 (1.03-2.86) | 0.04 | 2.20 (1.33-3.64) | 0.0021 | |

| TBI vs. BuCy | 1.28 (0.71-2.31) | 0.42 | 1.33 (0.79-2.25) | 0.28 | 1.91 (1.13-3.20) | 0.015 | |

| FL | |||||||

| BEAM | 1.00 | 0.105* | 1.00 | 0.042* | 1.00 | 0.005*1 | |

| CBVlow | 0.79 (0.58-1.08) | 0.23 | 0.72 (0.55-0.94) | 0.016 | 0.63 (0.45-0.87) | 0.0061 | |

| CBVhigh | 1.34 (0.90-2.00) | 0.12 | 1.16 (0.81-1.67) | 0.42 | 1.24 (0.83-1.86) | 0.30 | |

| BuCy | 0.82 (0.59-1.14) | 0.35 | 0.77 (0.58-1.03) | 0.08 | 0.69 (0.49-0.87) | 0.035 | |

| TBI | 1.03 (0.76-1.41) | 0.73 | 0.88 (0.66-1.16) | 0.35 | 0.93 (0.68-1.28) | 0.65 | |

| CBVhigh vs. CBVlow | 1.70 (1.10-2.61) | 0.02 | 1.62 (1.11-2.37) | 0.01 | 1.98 (1.28-3.06) | 0.0021 | |

| BuCy vs CBVlow | 1.04 (0.72-1.50) | 0.85 | 1.08 (0.79-1.48) | 0.63 | 1.10 (0.74-1.62) | 0.64 | |

| TBI vs. CBVlow | 1.31 (0.92-1.85) | 0.16 | 1.22 (0.91-1.65) | 0.19 | 1.48 (1.04-2.11) | 0.03 | |

| BuCy vs. CBVhigh | 0.61 (0.39-0.96) | 0.04 | 0.67 (0.45-0.99) | 0.05 | 0.55 (0.35-0.97) | 0.011 | |

| TBI vs. CBVhigh | 0.77 (0.50-1.19) | 0.23 | 0.76 (0.51-1.11) | 0.15 | 0.75 (0.49-1.15) | 0.18 | |

| TBI vs. BuCy | 1.26 (0.87-1.83) | 0.26 | 1.13 (0.82-1.56) | 0.45 | 1.35 (0.93-1.97) | 0.11 | |

| DLBCL | |||||||

| BEAM | 1.00 | 0.30* | 1.00 | 0.11* | 1.00 | 0.006*1 | |

| CBVlow | 1.05 (0.89-1.25) | 0.55 | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) | 0.73 | 1.04 (0.88-1.24) | 0.63 | |

| CBVhigh | 1.25 (0.99-1.57) | 0.06 | 1.26 (1.03-1.55) | 0.02 | 1.44 (1.16-1.77) | 0.0011 | |

| BuCy | 0.95 (0.77-1.17) | 0.62 | 0.99 (0.83-1.19) | 0.95 | 1.10 (0.91-1.33) | 0.32 | |

| TBI | 1.09 (0.84-1.41) | 0.52 | 1.19 (0.96-1.49) | 0.12 | 1.29 (1.02-1.62) | 0.03 | |

| CBVhigh vs. CBVlow | 1.19 (0.93-1.51) | 0.17 | 1.23 (1.00-1.51) | 0.05 | 1.38 (1.11-1.70) | 0.0031 | |

| BuCy vs CBVlow | 0.90 (0.72-1.13) | 0.36 | 0.97 (0.80-1.17) | 0.73 | 1.06 (0.86-1.29) | 0.59 | |

| TBI vs. CBVlow | 1.03 (0.79-1.35) | 0.81 | 1.16 (0.93-1.45) | 0.19 | 1.23 (0.98-1.56) | 0.07 | |

| BuCy vs. CBVhigh | 0.76 (0.58-0.99) | 0.04 | 0.79 (0.62-0.99) | 0.04 | 0.77 (0.61-0.97) | 0.03 | |

| TBI vs. CBVhigh | 0.87 (0.64-1.19) | 0.38 | 0.94 (0.73-1.22) | 0.67 | 0.90 (0.69-1.17) | 0.42 | |

| TBI vs. BuCy | 1.15 (0.85-1.54) | 0.36 | 1.20 (0.94-1.54) | 0.14 | 1.17 (0.91-1.50) | 0.23 | |

| MCL | |||||||

| BEAM | 1.00 | <0.001*1 | 1.00 | 0.24* | 1.00 | 0.81* | |

| CBVlow | 0.54 (0.34-0.84) | 0.0061 | 0.80 (0.58-1.12) | 0.19 | 1.08 (0.74-1.56) | 0.70 | |

| CBVhigh | 1.16 (0.74-1.84) | 0.51 | 0.94 (0.62-1.43) | 0.78 | 0.98 (0.60-1.59) | 0.94 | |

| BuCy | 1.14 (0.78-1.66) | 0.50 | 1.02 (0.73-1.42) | 0.90 | 1.23 (0.84-1.79) | 0.29 | |

| TBI | 0.52 (0.33-0.81) | 0.0041 | 0.71 (0.51-1.00) | 0.05 | 0.99 (0.68-1.44) | 0.95 | |

| CBVhigh vs. CBVlow | 2.17 (1.26-3.76) | 0.0051 | 1.17 (0.75-1.84) | 0.48 | 0.91 (0.55-1.51) | 0.72 | |

| BuCy vs CBVlow | 2.13 (1.31-3.44) | 0.0021 | 1.27 (0.88-1.84) | 0.20 | 1.14 (0.76-1.70) | 0.52 | |

| TBI vs. CBVlow | 0.97 (0.57-1.65) | 0.91 | 0.89 (0.62-1.27) | 0.51 | 0.92 (0.62-1.35) | 0.57 | |

| BuCy vs. CBVhigh | 0.98 (0.60-1.60) | 0.93 | 1.08 (0.69-1.70) | 0.73 | 1.25 (0.75-2.08) | 0.39 | |

| TBI vs. CBVhigh | 0.45 (0.26-0.77) | 0.0041 | 0.75 (0.48-1.19) | 0.22 | 1.01 (0.61-1.67) | 0.97 | |

| TBI vs. BuCy | 0.46 (0.28-0.74) | 0.0011 | 0.70 (0.48-1.01) | 0.06 | 0.81 (0.54-1.21) | 0.29 | |

Overall p-values

Comparisons significantly associated with an outcome (p < 0.01).

PFS and OS

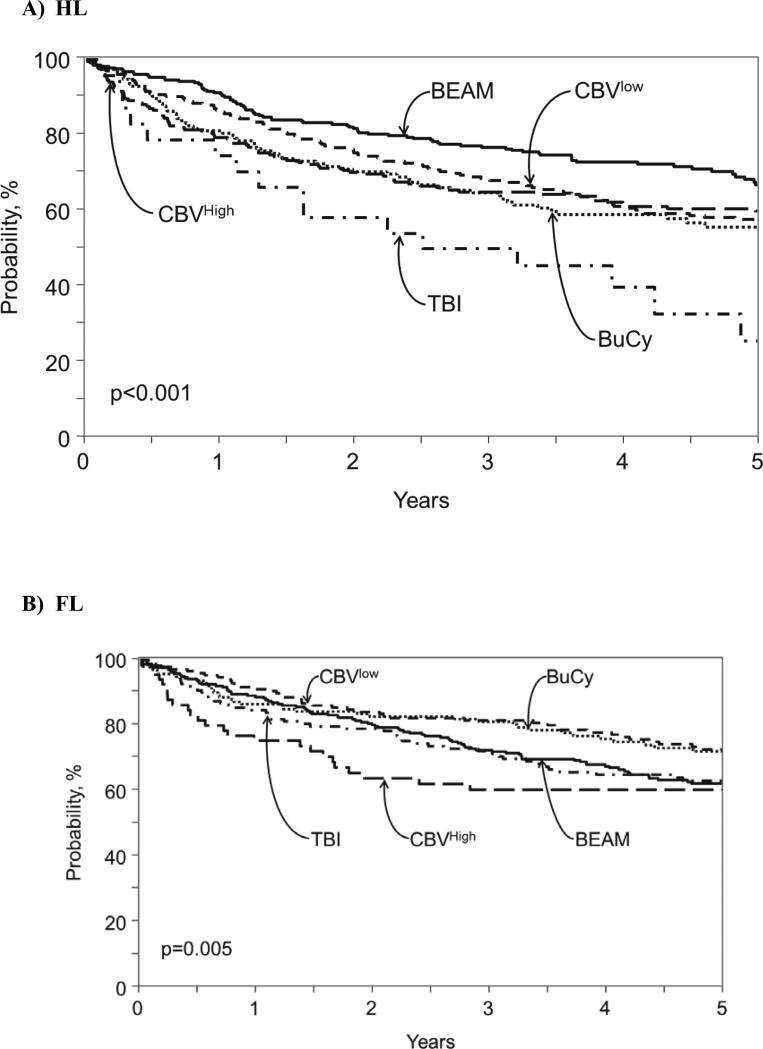

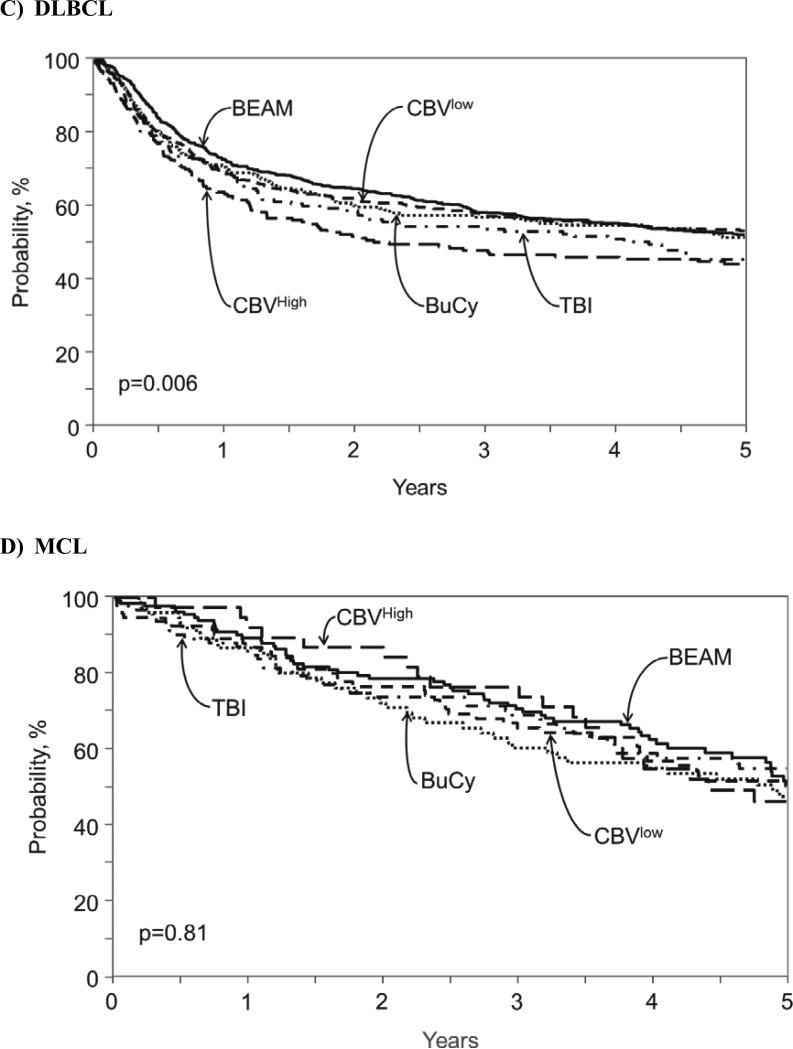

For patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, probabilities of three-year PFS were: BEAM (51% [48-53%]), CBVlow (52% [49-55]), CBVhigh (41% [36-46%]), BuCy (49% [45-53%]), and TBI (50% [45-54]). Table 3 shows three-year PFS and OS probabilities for the three most common NHL histologies: FL, FLBCL and MCL. Multivariate analysis for treatment failure (1-PFS) showed no specific impact of conditioning regimen on this outcome in FL, DLBCL or MCL. (Table 3). Probabilities of three-year OS were: BEAM (64% [61-66]), CBVlow (60% [57-64%]), CBVhigh (52% [47-57]), BuCy (59% [55-63]), and TBI (59% [55-63%]). . Multivariate analysis for overall mortality (Table 4) demonstrated that among patients with FL, CBVlow resulted in better outcomes compared to BEAM (HR 0.63, [0.45-0.87], p=0.006) and to CBVhigh (HR 0.50 [0.33-0.78], p=0.002). Among patients with with DLBCL, CBVhigh resulted in worse outcomes compared to BEAM (HR 1.44 [1.16-1.77], p=0.001) and CBVlow (HR 1.38 [1.11-1.70], p=0.003). All conditioning regimens resulted in similar overall survival among patients with MCL. Figure 1A-C shows overall survival for each NHL histology.

Figure 1.

Adjusted probability of overall survival after autologous hematopoietic cell transplant for (A) Hodgkin lymphoma, (B) follicular lymphoma, (C) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and (D) mantle cell lymphoma according to conditioning regimen.

For patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, probabilities of three-year PFS were: BEAM (62% [56-67%]), CBVlow (60% [54-66%]), CBVhigh (57% [50-64%]), BuCy (51% [43-59%]), and TBI (43% [24-63]). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that BuCy (HR 1.51 [1.15, 1.97], p=0.003) and TBI (HR 2.01, [1.21, 3.34], p=0.007) had worse PFS compared to BEAM (Table 4). Probabilities of three-year OS were: BEAM (79% [74-83]), CBVlow (73% [68-79]), CBVhigh (68% [61-74]), BuCy (65% [58-73]), and TBI (47% [27-68%]) (Figure 1D). Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with HL receiving BEAM had superior overall survival compared to all other regimens (Table 4). Factors associated with inferior OS for all patients included older age, male gender, BMI < 18.5, KPS < 90, chemo-resistant disease, higher number of previous regimens of chemotherapy received, shorter time from diagnosis to AHCT, and use of bone marrow (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large retrospective registry study of patients with NHL and HL, we analyzed the impact of several commonly used high-dose therapy regimens (BEAM, CBVlow, CBVhigh, BuCy and TBI) for AHCT on outcomes including IPS, TRM, relapse or progression, PFS, and OS. The results demonstrated clear differential outcomes according to the conditioning regimen utilized with NHL or HL. For all patients, the development of IPS significantly increases the risk of death after AHCT and the incidence of IPS was higher in patients receiving higher doses of BCNU and TBI-based regimens. For patients with NHL, the outcomes further differed by specific disease histologies, with CBVlow associated with better survival for FL, CBVhigh being worse for DLBCL and no difference in survival according to the conditioning regimens studied among patients with MCL. Among patients with HL, BEAM was associated with better survival compared to all other regimens.

In this analysis, the development of IPS was most common after CBVhigh (6%) or TBI-based (5%) regimens, and patients who developed IPS had much worse PFS and OS. The most recently published series investigating pulmonary toxicity following AHCT was a retrospective study on 222 patients with lymphoma receiving a CBVhigh regimen at Massachusetts General Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Clinical factors associated with pneumonitis included prior mediastinal radiation, total BCNU dose ≥ 1000 mg, and age < 54 years. Importantly, 3 of the 4 cases of TRM in their cohort were due to pneumonitis.12 While the dose of BCNU was found to be a risk factor for IPS in the current study, mediastinal radiation could not be validated as this data was not comprehensively available. However, the fact that HL was associated with the diagnosis of IPS suggests that the treatment of HL, which commonly includes radiation, could be contributing to the increased risk. The association of older age (rather than younger) with an increased risk of pneumonitis may reflect patients with pre-existing pulmonary disease, however, routine pulmonary function data was also not available.

While the choice of specific HDT regimen did not influence the risk of TRM when adjusted for all clinical variables, several characteristics were associated with an increased risk of TRM, including older age, male gender, KPS < 90%, chemo-resistant disease, higher number of previously received chemotherapy regimens, earlier year of AHCT, history of smoking, and use of bone marrow. Most of these variables reflect patient co-morbidities or significant changes in supportive care and patient selection over time, and have previously been shown to be associated with TRM after AHCT.

Interestingly, the impact of HDT regimen on the risk of disease relapse or progression differed in NHL vs. HL. For example, patients with MCL who received CBVlow or TBI experienced lower rates disease progression. For patients with HL, those who received either BuCy or TBI-based regimens had a significantly increased risk of relapse compared to patients who received BEAM or either CBV regimen. Of greater interest, these effects translated into better overall survival outcomes in some subsets. For example, in FL the use of CBVlow was associated with better survival, but there was no effect on disease progression or TRM. One explanation is that there are few TRM events after AHCT which makes it challenging to observe differences within each disease histology. Progression after AHCT is a much more common event, and therefore if a conditioning regimen results in inferior disease control and is associated with higher toxicity this may translate into higher overall mortality.

These findings are noteworthy given that many practitioners are of the opinion that all standard HDT regimens yield similar outcomes across all lymphoma types as long as myeloablative doses are employed. This belief is supported by many single-arm series and the study by Vose et al from the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) 18 describing outcomes of different regimens, all of which show comparable results but are impossible to directly compare to one another. Appropriately, in recent years, most centers have moved away from using TBI-based regimens given the long-term sequelae of TBI,19-21 particularly the increased risk for secondary malignancies.22 Moreover, retrospective studies have suggested improved efficacy with chemotherapy-alone regimens compared to those which are TBI-based.23-25

Recent studies support our finding of the superiority of BEAM for HL. The Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group performed a retrospective analysis on 225 patients with HL who received AHCT between 1984 and 2007. Importantly, they only included patients who were alive after 2 years, and compared outcomes of BEAM vs. CBV. At 10 years, PFS was 79% for BEAM and 59% for CBV (p=0.01) and OS was 84% for BEAM vs. 66% for CBV (p=0.02).26 More recently, investigators used a matched control analysis to compare outcomes of a cohort of 184 lymphoma patients enrolled on a multi-center phase II study of AHCT following BuCyE (intravenous Bu, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) to controls who received BEAM from the CIBMTR database. Toxicity and TRM appeared to be comparable between the groups. Outcomes for patients with NHL were equivalent between BuCyE and BEAM, however, for patients with HL, patients receiving BuCyE had a significantly higher rate of progression and much shorter PFS.27 Recently, investigators have incorporated newer agents into traditional high-dose regimens. Visani et al. conducted a phase I/II study on 43 patients using BeEAM (bendamustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) conditioning for AHCT for relapsed / refractory lymphoma and showed an impressive CR rate of 81% at a median follow-up of 18 months.28 Vose et al. have conducted several trials combining 131-Iodine tositumomab with BEAM for AHCT, but no clear advantage was observed in the phase III trial.18,29,30 Other trials have studied Gem-Bu-Mel (gemcitabine, busulfan and melphalan)31, Bu-Mel-TT (busulfan, melphalan and thiotepa)32, and the additions of (90)Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan33 or Bortezomib,34 respectively, to BEAM conditioning. Clearly, prospective randomized trials will determine if incorporation of these newer agents into HDT regimens has significant value, but based on our results,the selection of the control needs to take into account the differences in outcomes based on histologies..

The limitations of our analysis are those inherent to any large registry study. For example, the patients who received BEAM were predominantly treated in a more recent era, and thus, any improvements observed could have been partly due to improved supportive care, patient selection, or salvage therapy. These variables may not be well adjusted for in our multivariate model, although year of transplant and source of stem cells were included and were not significantly associated with outcomes. In addition, the regimens were given heterogeneously, according to individual center standards, which includes the order and rate of chemotherapy administration, use of systemic corticosteroids as anti-emetics, and institution specific supportive care, all of which could influence toxicities such as the development of IPS. The method by which the diagnosis of IPS was made was based on the individual center's definition of IPS and the lack of pulmonary infection. Given the large number of patients treated at many centers over many years, individual cases could not be validated centrally. Furthermore, we were unable to analyze if pre-existing pulmonary dysfunction (as defined by standard pulmonary function tests) influenced the development of IPS given the incompleteness of available data. The study compare the most common high dose regimens used in lymphoma, however, in some subgroups, for example recipients of TBI for HL the numbers are too small. This needs to take into consideration when interpreting the results.

In summary, we have conducted the largest study to date on lymphoma patients undergoing AHCT, comparing outcomes of five commonly used HDT regimens. In this large cohort, IPS was a significant complication of all regimens, but more commonly observed after CBVhigh or TBI-based regimens. The development of IPS had a profoundly negative effect on overall survival. In terms of overall survival, patients with FL appeared to do best with CBVlow, while patients with HL appeared to do best with BEAM. Regimens with higher doses with BCNU were associated with higher incidences of IPS, and in DLBCL resulted in higher mortality. In conclusion, there is variability in toxicity and disease outcomes among specific AHCT regimens. Further analyses in specific lymphoma subtypes are important to understand the best regimen that maximizes disease control with lower toxicities.

Key points.

Different high-dose therapy regimens resulted in different outcomes based on Hodgkin vs. non-hodgkin lymphoma.

Compared to other high-dose therapy regimens, BEAM gives the best outcomes for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Compared to BEAM, CBVlow results in better survival for patients with follicular lymphoma

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-13-1-0039 and N00014-14-1-0028 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; *Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; *Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; *Celgene Corporation; Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; *Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.;*Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Jeff Gordon Children's Foundation; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac GmbH; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; *Milliman USA, Inc.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; *Remedy Informatics; *Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; St. Baldrick's Foundation; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; *Tarix Pharmaceuticals; *TerumoBCT; *Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; *THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Minnesota; University of Utah; and *Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

*Corporate Members

Footnotes

Authorship: Y.C. and A.A.L. designed the research, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and contributed equally to this study. B.L., X.Z., G.A., M.A., A.A., C.N.B., K.R.C., V.T.H., H.M.L., R.O., W.S., P.M., and M.C.P. contributed to the design of the research, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Colpo A, Hochberg E, Chen YB. Current status of autologous stem cell transplantation in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. Oncologist. 2012;17:80–90. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moskowitz AJ, Moskowitz CH. Controversies in the treatment of lymphoma with autologous transplantation. Oncologist. 2009;14:921–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nademanee A. Transplantation for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2009;2:425–42. doi: 10.1586/ehm.09.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez HF, Escalon MP, Pereira D, et al. Autotransplant conditioning regimens for aggressive lymphoma: are we on the right road? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:505–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afessa B, Abdulai RM, Kremers WK, et al. Risk factors and outcome of pulmonary complications after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Chest. 2012;141:442–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong R, Rondon G, Saliba RM, et al. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high-risk breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:1157–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benekli M, Smiley SL, Younis T, et al. Intensive conditioning regimen of etoposide (VP-16), cyclophosphamide and carmustine (VCB) followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:613–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horning SJ, Chao NJ, Negrin RS, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin's disease: analysis of the Stanford University results and prognostic indices. Blood. 1997;89:801–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nademanee A, O'Donnell MR, Snyder DS, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with or without total body irradiation followed by autologous bone marrow and/or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin's disease: results in 85 patients with analysis of prognostic factors. Blood. 1995;85:1381–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puig N, de la Rubia J, Remigia MJ, et al. Morbidity and transplant-related mortality of CBV and BEAM preparative regimens for patients with lymphoid malignancies undergoing autologous stem-cell transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1488–94. doi: 10.1080/10428190500527769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reece DE, Barnett MJ, Connors JM, et al. Intensive chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, carmustine, and etoposide followed by autologous bone marrow transplantation for relapsed Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1871–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.10.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane AA, Armand P, Feng Y, et al. Risk factors for development of pneumonitis after high-dose chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, BCNU and etoposide followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1130–6. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.645208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasquini MC, Wang Z, Horowitz MM, et al. 2010 report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR): current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplants for blood and bone marrow disorders. Clin Transpl. 2010:87–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caballero MD, Rubio V, Rifon J, et al. BEAM chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell support in lymphoma patients: analysis of efficacy, toxicity and prognostic factors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:451–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheeler C, Antin JH, Churchill WH, et al. Cyclophosphamide, carmustine, and etoposide with autologous bone marrow transplantation in refractory Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a dose-finding study. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:648–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.4.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulrickson M, Aldridge J, Kim HT, et al. Busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Bu/Cy) as a preparative regimen for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a single-institution experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1447–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vose JM, Carter S, Burns LJ, et al. Phase III randomized study of rituximab/carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) compared with iodine-131 tositumomab/BEAM with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the BMT CTN 0401 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1662–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majhail NS, Ness KK, Burns LJ, et al. Late effects in survivors of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the bone marrow transplant survivor study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisk P, Arvidson J, Bratteby LE, et al. Pulmonary function after autologous bone marrow transplantation in children: a long-term prospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:645–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subira M, Sureda A, Martino R, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for high-risk Hodgkin's disease: improvement over time and impact of conditioning regimen. Haematologica. 2000;85:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sureda A, Arranz R, Iriondo A, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation for Hodgkin's disease: results and prognostic factors in 494 patients from the Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Transplante Autologo de Medula Osea Spanish Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1395–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caballero MD, Perez-Simon JA, Iriondo A, et al. High-dose therapy in diffuse large cell lymphoma: results and prognostic factors in 452 patients from the GEL-TAMO Spanish Cooperative Group. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:140–51. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez-Delgado F, Maloney DG, Press OW, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: comparison of radiation-based and chemotherapy-only preparative regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:455–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salar A, Sierra J, Gandarillas M, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for clinically aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: the role of preparative regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:405–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.William BM, Loberiza FR, Jr., Whalen V, et al. Impact of conditioning regimen on outcome of 2-year disease-free survivors of autologous stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:417–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasquini MC, Rademacher JL, Flowers C, et al. Matched Pair Comparison of Busulfan/Cyclophosphamide/Etoposide (BuCyE) to Carmustine/Etoposide/Cytarabine/Melphalan (BEAM) Conditioning Regimen Prior to Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (autoHCT) for Lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant: ASBMT abstract. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visani G, Malerba L, Stefani PM, et al. BeEAM (bendamustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) before autologous stem cell transplantation is safe and effective for resistant/relapsed lymphoma patients. Blood. 2011;118:3419–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-351924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vose JM, Bierman PJ, Enke C, et al. Phase I trial of iodine-131 tositumomab with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for relapsed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:461–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vose JM, Bierman PJ, Loberiza FR, et al. Phase II trial of 131-Iodine tositumomab with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nieto Y, Popat U, Anderlini P, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for refractory or poor-risk relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma: effect of the specific high-dose chemotherapy regimen on outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:410–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bains T, Chen AI, Lemieux A, et al. Improved outcome with busulfan, melphalan and thiotepa conditioning in autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:583–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.806659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krishnan A, Palmer JM, Tsai NC, et al. Matched-cohort analysis of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation with radioimmunotherapy versus total body irradiation-based conditioning for poor-risk diffuse large cell lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:441–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.William BM, Allen MS, Loberiza FR, Jr., et al. Phase I/II Study of VELCADE(R)-BEAM (V-BEAM) and Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (ASCT) for Relapsed Indolent Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Transformed, or Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]