Introduction

An estimated 7.1 million U.S. children have asthma with African American children experiencing higher asthma morbidity and a 7.6 times higher mortality rate than non-Hispanic white children.1, 2 Although the cause for the increased morbidity and mortality are multifold, inappropriate use of asthma medications has been reported as a major contributor to uncontrolled asthma among inner-city populations.3, 4 Although the elevated rates of asthma morbidity and mortality experienced by minority inner-city children are widely known, these children have increased odds of overusing short acting B2 agonist (SABA) on a daily basis3 and are the least likely to receive adequate guideline based therapy 5-7 or specialty care for asthma.8-10 Frequent use of SABA medication is a key indicator of poor asthma control. 5,11-14 Use of 3 or more SABA canisters per year by children with asthma has been found to be associated with a 2-fold increase in risk of asthma-related hospitalization or emergency department (ED) visit. 15

Several explanations for the increased SABA use in inner-city children have been proposed. Allergen sensitization and exposure are reported to be associated with increased asthma morbidity and SABA use.16 Multiple allergen sensitization and exposure may result in greater adverse effects than sensitization and exposure to a single allergen.17 The type of housing available to families of inner-city children with asthma are known to have high levels of multiple environmental allergens such as mouse, cockroach, cat, mold and dust mite.18 Exposure to these major allergens can result in an increased risk for allergen sensitization, recurrent wheezing19 and increased ED visits and hosptilatizations.20 In addition, low-income, inner-city children are more frequently exposed to second hand smoke (SHS) than non-poor children. 10, 21-23 Indoor SHS exposure, particularly maternal smoking, was associated with a 52% increased risk of wheeze and 20% increased risk of asthma at age 5-18 years,24 and any home SHS exposure was associated with increased asthma symptoms.25 Identifying factors associated with frequent SABA medication use, indicative of poor asthma control, including allergen sensitization and indoor exposures to allergens and SHS may be helpful in targeting individualized environmental control as well as community level asthma interventions for inner-city families. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine factors, including allergic sensitization and second hand smoke (SHS) exposure, associated with high SABA use among low-income inner-city children with frequent ED visits for asthma.

Methods

Study Design and population

This manuscript presents a sub-analysis of baseline data on n=100 participants enrolled in an ongoing randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of an ED and home-based environmental control intervention for children with frequent ED visits for asthma. One primary aim of the intervention was to increase controller medication use and decrease SABA use when indicated. The primary outcome of this sub-analysis was the level of SABA use over 12 months. The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Children were recruited, consented and enrolled during an ED visit for treatment of an acute asthma exacerbation (ED enrollment visit). Data were collected from August 2013 through October 2014. Inclusion criteria were physician diagnosed persistent asthma and uncontrolled asthma based on current National Asthma Education Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines,13 2 or more ED asthma visits or ≥ 1 hospitalization due to asthma during the past 12 months, aged 3-12 years and residence in the Baltimore metropolitan area. Children were excluded if they had significant other non-asthma respiratory conditions such as cystic fibrosis, were enrolled in another asthma study, refused blood draw for RAST testing, or were homeless and/or lacked access to a phone for delivery of the home intervention. After screening 177 children with asthma in the ED, 153 children were eligible. Out of the 153 eligible children, 100 met inclusion criteria, agreed to participate, and were enrolled in the study. (Figure 1) After written informed consent was obtained from each child’s primary caregiver/legal guardian and verbal assent from children over age 8 years, children were randomly assigned to either ED-home based intervention or an attention control group in a 1:1 ratio. During the enrollment ED visit, all children received (1) serologic allergen specific IgE testing (RAST) to assess sensitization to ten common indoor and outdoor allergens and (2) saliva collected to measure cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, to determine their level of second hand smoke (SHS) exposure. RAST and cotinine test results were sent to each child’s primary care provider (PCP) and caregiver within 1-2 weeks post enrollment ED visits as part of the ED and home environmental control intervention. Control PCPs and caregivers received the same information at the end of the 3 month control intervention period.

Figure 1. Recruitment Flow Diagram.

Measurement of Variables

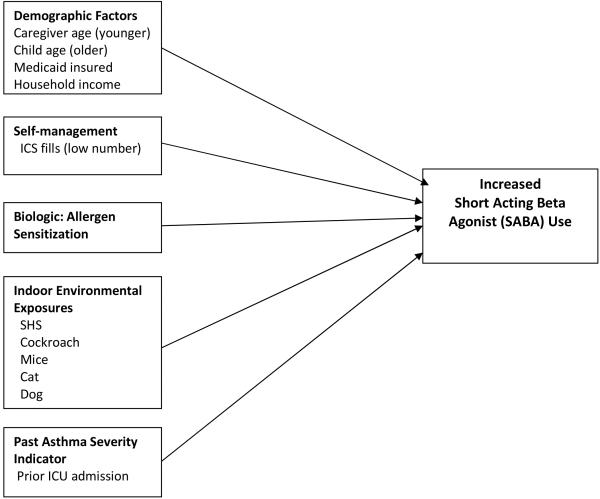

The hypothesized factors associated with high SABA use among inner-city children with frequent ED visits for asthma and examined in this analysis are shown in Figure 2. The model includes demographic factors (caregiver and child age, Medicaid insurance, household income), self-management (low use of inhaled corticosteroids), biologic or allergic sensitization factors, indoor environmental exposures (SHS, cockroach, mice, cat and dog) and a prior ICU admission as an indicator of more severe asthma. Measurement of these individual variables is described below.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model for Factors Associated with Increased Short Acting Beta Agonist (SABA) Use.

Frequency of short-acting beta agonist (SABA) medication

The primary outcome for this analysis was the frequency of SABA use during the 12 months prior to the enrollment ED visit and was based on pharmacy records. Pharmacy records of all asthma medications dispensed over the 12 month period prior to the baseline interview including the dispensing date, product name, strength, dosage form, and quantity dispensed were used as an objective measure of asthma medication use. Pharmacy records were obtained from all pharmacies listed by the caregiver as being used in the 12 month baseline period. Number of SABA canisters, defined as SABA fills per 12 months, was examined across all participants and high SABA use was defined as SABA fills in the top quartile (>75%; 4 or more fills) with all others classified as low/moderate use. Additionally, caregivers reported the number of days of SABA use during the prior 2 weeks.

Frequency of Inhaled Corticosteroid (ICS) Fills as a Proxy for Caregiver Self-management Behavior

Number of ICS fills per 12 months, calculated from pharmacy record data, was selected as the measure of anti-inflammatory exposure because they were the most commonly filled controller medication. In addition, caregiver report of controller medication use and oral corticosteroid courses over the past 6 months were ascertained during the baseline survey.

Sociodemographic Covariates

Surveys administered at baseline via face-to-face interview assessed demographic characteristics such as age, gender and race of the child and age, relationship to child, educational, employment status and income level of the primary caregiver. Income level was categorized into three groups: 0-$19,000, $20-$39,000 and >$40,000 per year .Medicaid insurance status of the child was also ascertained at baseline.

Allergen Sensitization: Serologic allergen specific IgE test (Radioallergosorbent Test, RAST)

To perform the RAST test, a total of 6 ml of blood was obtained from the child during the ED enrollment visit and sent to a private laboratory for analysis. The RAST was performed using the immunoassay (ImmunoCap®) Childhood Allergy Profile that measures IgE antibodies for common allergens: mouse, cockroach, cat, dog, timothy grass, Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus, oak tree, common ragweed and dermatophagoides farina (house dust mite). The degree of sensitization ranged from <0.35 to >100 kU/L of specific IgE to any of the allergens tested.

Cotinine Analysis for Second Hand Smoke (SHS) Exposure

Child saliva samples were collected during the index ED asthma visit. A 3-cm cotton swab (Salimetrics, State College, PA) was placed under the child’s tongue for 1 minute to absorb a minimum of 1 ml of saliva. The cotton roll was placed in a 2 ml vial and stored at −20° Centigrade prior to transport to the lab, then centrifuged and analyzed at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) lab using enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) analysis. The cotinine analysis serves as a biomarker of nicotine exposure over the prior 24 hours. The lower limit of cotinine sensitivity was 0.05 ng/ml and average intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation were less than 5.8% and 7.9%, respectively. A cotinine cutoff level of 1.0 ng/ml was used to define positive SHS exposure based on comparable samples of inner-city children with asthma. 26, 27

Indoor Environmental Exposure Assessment

Data on indoor exposure to cats, dogs, mice, rats or cockroaches, and the number of smokers in the home, smoker’s relationship to the child and type of home smoking ban (total, partial or some restrictions and no restrictions) were reported by the caregiver on the baseline questionnaire at the ED enrollment visit.

Asthma Morbidity and Healthcare Utilization

Asthma morbidity measures included the number of symptom days and nights over the past 2 weeks based on current National Asthma Education Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines. 13 Caregiver’s were asked to rate their perception of the child’s asthma control over the past 4 weeks into 3 categories including “controlled”, “not controlled” or “unsure”. Caregiver understanding of the child’s asthma control was not ascertained. Healthcare utilization measures included the number of asthma ED visits, hospitalizations for asthma, and primary care provider (PCP) visits for routine asthma care reported over the past 3 months. Office urgent care visits for asthma were not included in ED asthma visit counts in order to target high cost utilization. Caregiver report of any lifetime ICU admission for asthma, indicative of children at high risk for future life-threatening exacerbations, was confirmed with electronic medical record (EMR) review. High concordance (83% agreement) was found between caregiver report and EMR for lifetime ICU admission.

Statistical Analysis

Standard frequencies were used to describe baseline demographic and health related variables for all children. The primary outcome, number of SABA fills over the past 12 months was categorized into two groups: low/moderate use (first to third quartile of fills) versus high use. High SABA use was defined as the upper quartile of SABA fills over 12 months (4 or more SABA fills over 12 months). Mean SABA fills over 12 months was 3.12 fills and is higher than prior reports of SABA use in a comparable group of high risk children with asthma after an ED asthma visit (mean of 1.90 SABA canisters per 12 months).28 Due to the non-normal distribution of salivary cotinine concentrations, all cotinine values were log transformed for analysis as a continuous variable. To control for asthma seasonality, a season variable was created with season based on the date of the ED enrollment visit. Unadjusted odds ratios were calculated using logistic regression for associations between high SABA use by child age, caregiver perception of asthma control, exposure to SHS and exposure to indoor allergens, season of enrollment ED visit, allergen sensitizations and any prior ICU admission. Student’s t-test and ANOVA were used to compare the two SABA groups by the continuous variables including symptom days and nights, number of ED visits and hospitalizations. Forward conditional stepwise multivariate logistic regression was used to predict high SABA use while adjusting for caregiver and child age (categorized as 3-5 versus 6-12 years), child gender, income, number of ICS fills, cockroach allergy sensitization status, prior ICU asthma admission, receipt of asthma specialty care and cotinine level (categorized as positive versus negative). Variable selection criteria for inclusion in the model were entry set at p=0.35 and variable exclusion at p<0.30. Two-sided tests were used and p values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 22 software. 29

Results

Study Population

A demographic description of the study sample is provided in Table 1. Child participants were primarily African American (95%), male (56%) and Medicaid insured (97%) with a mean age 6.3 years (SD 2.6). Caregivers were predominantly the child’s biological mother (93%). Most caregivers were single (77%), high school graduates or greater education (81%), employed (56%) and had a household income of <$30,000 (67%).

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Sample (N=100)

| Total N (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | |

| Age years (Mean, SD) 3-5 years 6-12 years |

6.25 (2.6) 50 (50.0) 50 (50.0) |

| Gender Male Female |

56 (56.0) 44 (44.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity African American White Other |

95 (95.0) 1 ( 1.0) 4 ( 4.0) |

| Medical Insurance (n=99) Medicaid Private Insurance No insurance |

96 (97.0) 3 ( 3.0) 0 ( 0.0) |

| Caregiver Characteristics | N (%) |

| Age years (Mean, SD) Range 19-58 yrs |

31.8 (7.8) |

| Relationship to child Biological mother Grandmother Missing |

93 (93.0) 4 ( 4.0) 3 ( 3.0) |

| Education (N=91) < 9th grade Some HS HS grad or GED Some college or more |

2 ( 2.0) 17 (17.0) 38 (38.0) 43 (43.0) |

| Marital Status (N=99) Single Married Divorced/separated/Widow Other |

76 (76.8) 16 (16.2) 6 ( 6.0) 1 ( 1.0) |

| Employment Status Part time Fulltime Unemployed/other |

13 (13.0) 43 (43.0) 44 (44.0) |

| Income (n=99) < $10,000 $10,000-29,000 $30,000-39,000 >$ 40,000 Refused |

35 (35.4) 31 (31.3) 10 (10.1) 14 (14.1) 9 ( 9.1) |

| Medication Use Characteristics | N (%) |

| SABA Use (Pharmacy fills over 12 months) Mean (SD) Range High use (top quartile) range |

3.12 (2.8) 0-18 4.25-18 |

| Inhaled Corticosteroid (ICS) Use (Pharmacy fills over 12 months Mean (SD) Range |

2.09 (2.9) 0-16 |

| Controller Medication Use past 2 weeks Yes No |

77 (77.0) 23 (23.0) |

| Duration of SABA medication canister (n=98) < 1 month 1-2 months 3 or more months |

30 (30.6) 47 (48.0) 21 (21.4) |

| Duration of Controller Medication canister (N=77) <1 month 1-2 months 3 or more months |

25 (32.5) 46 (59.7) 6 ( 7.8) |

| Number of oral steroid courses reported past 3 months (mean, SD) |

3.04 (2.8) |

| HealthCare Utilization Characteristics | N (%) |

| Primary Care Provider (PCP) visit for asthma past 3 months 1 or more visits |

54 (54) |

| Specialty Care for Asthma in past Yes |

20 (20) |

| Number asthma-related ED visits for asthma past 3 months (mean, SD) |

1.37 (1.0) |

| Number asthma-related hospitalizations past 3 months (mean, SD) |

0.12 (0.4) |

| Prior ICU admission (lifetime)-medical record confirmed Yes |

31 (31.0) |

| Asthma Control past 4 weeks (caregiver report) Well controlled Not well controlled Unsure |

51 (51.0) 42 (42.0) 7 ( 7.0) |

| Allergen Sensitization and Exposure Characteristics | N (% ) |

| Positive Allergy Sensitization Dog Cat Mouse Cockroach Timothy Grass Dermatophagoides Oak tree Aspergillus fumigatus Alternaria alternate Ragweed |

56/92 (60.9) 52/92 (56.5) 45/87 (51.7) 40/90 (44.4) 39/92 (42.4) 38/89 (42.7) 38/91 (41.8) 30/91 (33.0) 31/91 (34.1) 29/92 (31.5) |

| Any positive allergy Yes |

73/91 (80.2) |

| Number of smokers in the home None 1 2 3 or more Mother is smoker (n=57 smokers) |

43 (43.0) 34 (34.0) 16 (16.0) 7 ( 7.0) 19/57 (33.3) |

| Cotinine Log (mean, SD) | 0.13 (0.4) |

| N (%) | |

| Cotinine Positive (n=98) ≥ 1.0 ng.ml |

53 (54.1) |

| Rodents and Roaches in home by self-report Mice (yes) Cockroaches (yes) Rats (yes) |

50/100 (50.0) 45/100 (45.0) 7/100 ( 7.0) |

| Pets in home by self-report Dogs (yes) Cats (yes) |

18/99 (18.2) 30/99 (30.3) |

| Mice + Cat in home Yes |

16/100 (16.0) |

Children were highly atopic with 80% sensitized to 1 or more allergens tested. The most common positive allergen sensitizations were dog (61%), cat (57%), mouse (52%) and cockroach (44%). Older children, aged 6-12 years, had significantly higher rates of positive allergen sensitivity rates for all allergens except mouse, cat and Aspergillus as compared to younger children aged 3-5 years. (Figure 3). Indoor exposure to allergens was high for mouse (50%), cockroach (45%), and cats (30%); concurrent cat and mouse exposure was reported in 16% of homes. Child age was not associated with indoor exposure to cat, dog, cockroach or mice. Exposure to SHS was high with 54% of children having cotinine levels consistent with SHS exposure (>1.0 cotinine) and 57% of caregivers reporting 1 or more cigarette smokers in the home. Percent agreement of positive cotinine and caregiver report of a smoker in the home was moderate at 65% (Kappa 0.30, p=0.003) indicating some misclassification of SHS exposure based on caregiver report. One-third of the smokers were identified as the caregiver.

Figure 3.

Percent of Children with Positive Allergen Sensitization by Age Group.

SABA Use and Healthcare Utilization Characteristics

SABA use was high with over one-quarter (27%) reporting daily use over the past 2 weeks. Mean SABA fills over 12 months was 3.12 (SD2.8) with a range of 0-18 fills. There was no seasonal trend for mean SABA fills (F=0.49, df =3, p=0.69). One quarter of children had 4 or more SABA fills over 12 months and 16% had 6 or more SABA fills over the same time period. Health care utilization was high with mean ED visits in the past 3 months at 1.37 (SD1.0) and mean hospitalizations at 0.12 (SD 0.4) over same time period. Further, almost one-third (31%) had a confirmed lifetime ICU asthma admission. Despite high SABA use, high ED utilization and many with a prior ICU admission for asthma, most caregivers rated their child’s asthma control as well controlled (51%) at baseline.

Factors Associated with High SABA Medication Use

Based on the unadjusted bivariate analysis, children with high SABA use were over 5 times more likely to have a hospitalization for asthma within the past 3 months than children with low to moderate SABA use (Table 2). Further, children with high SABA use were almost 3 times more likely to have a prior ICU admission, over 3 times more likely to have received specialty asthma care for asthma, and 3 times more likely to have positive cockroach sensitization. Mean number of PCP visits was almost twice as high for the high SABA use group as compared to the low/moderate SABA use group. Mean inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) fills were almost four times higher in the high versus low to moderate SABA use group (Low to moderate SABA, mean (SD): 1.31 (2.2); High SABA: 4.07 (3.5), p<0.001) indicating controller medication use with high SABA use. Residing with a smoker in the home was not significantly associated with high SABA use, although two-thirds of the high SABA use group reported a smoker in the home versus only half of the low/moderate SABA use group. A positive cotinine level, or reported mouse or cockroach exposure in the home were not associated with high SABA use. Season of the ED enrollment visit was not associated with high SABA use (X2 =3.20, df=3, p=0.36).

Table 2.

High SABA Use by Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics by (N=100)

| Characteristic | Low to moderate SABA use N= 73 |

High SABA Use N=27 |

Total N= 100 |

Statistic OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| Child Age 3-5 years 6-12 years (reference group) |

36 (49.3) 37 (50.7) |

14 (51.9) 13 (48.1) |

50 (50.0) 50 (50.0) |

OR:0.90 (0.37, 2.19) |

| Caregiver Age Mean (SD) |

31.56 (8.3) |

32.27 (6.6) |

31.76 (7.8) |

F=0.15, df=1, p=0.70 |

| Health Characteristics | ||||

| Specialty Care for asthma Yes No (reference group) |

10 (13.7) 63 (86.3) |

10 (37.0) 17 (63.0) |

20 (20.0) 88 (80.0) |

OR:3.71 (1.33, 10.35)a |

| ICU or ventilator in past (confirmed) Yes No (reference group) |

18 (24.7) 55 (75.3) |

13 (48.1) 14 (51.9) |

31 (31.0) 69 (69.0) |

OR:2.84 (1.13, 7.15)b |

| Number PCP visits for asthma routine care past 3 months (mean, SD) |

0.70 (0.88) |

1.37 (1.4) |

0.88 (1.08) |

F=8.25, df=1, p=0.005 |

| ED visit for asthma past 3 months Yes No |

57 (78.1) 16 (21.9) |

24 (88.9) 3 (11.1) |

81 (81.0) 19 (19.0) |

OR 2.25 (0.60, 8.42) |

| Hospitalized for asthma past 3 months Yes No |

4 ( 5.6) 67 ( 94.4) |

7 (25.9) 20 (74.1) |

11 (11.2) 87 (88.8) |

OR 5.86 (1.56, 22.08)a |

| Number of Symptom Days past 2 weeks (mean, SD) |

5.03 (4.5) |

6.22 (4.7) |

5.35 (4.6) |

F=1.36, df=1, p =0.25 |

| Number of Symptom Nights past 2 weeks (mean, SD) |

5.70 (7.9) |

6.96 (8.5) |

6.04 (8.1) |

F=0.48, df=1, p=0.49 |

| Asthma Controlled (Parent Report) N=92) Yes No (reference group) |

38 (56.7) 29 (43.3) |

13 (50.0) 13 (50.0) |

51 (54.8) 42 (45.2) |

OR: 1.31 (0.53, 3.25) |

| Medication Use Characteristics | ||||

| Rescue medication canister duration (200 sprays) <1 month 1 or more months |

18 (25.4) 53 (74.6) |

12 (44.4) 15 (55.60 |

30 (30.6) 68 (69.4) |

OR: 0.43 (0.17, 1.07) |

| Mean (SD) Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) fills past 12 months |

1.31 (2.2) |

4.07 (3.5) |

2.09 (2.9) |

F=21.0, df=1, p <0.001 |

| Indoor Exposures and Allergen Sensitization Results | ||||

| Smoker in the home None (reference) 1 or more |

36 (49.3) 37 (50.7) |

9 (33.3) 18 (66.7) |

45 (45.0) 55 (55.0) |

OR: 1.95 (0.77, 4.89) |

| Mother is smoker Yes No |

14 (19.2) 59 (80.8) |

5 (18.5) 22 (81.5) |

19 (19.0) 81 (81.0) |

OR:0.96 (0.31, 2.97) |

| Cotinine at Baseline Positive (≥ 1.0 ng/ml) Negative (< 1.0 ng/ml) |

39 (53.2) 33 (45.8) |

14 (53.8) 12 (46.2) |

53 (54.1) 45 (45.9) |

OR:0.99 (0.40, 2.43) |

| Mean cotinine (SD) | 1.98 (2.0) | 2.79 (4.6) | 2.19 (2.9) | t= −1.23, p=0.22 |

| Any positive allergy test c

Yes No |

56 (80.0) 14 (20.0) |

19 (82.6) 4 (17.4) |

75 (80.6) 18 (19.4) |

OR:1.19 (0.35, 4.05) |

| Cockroach Sensitization Positive Negative |

25 (37.3) 42 (62.7) |

15 (65.2) 8 (34.8) |

40 (44.4) 50 (55.6) |

OR:3.15 (1.17, 8.48)b |

| Cockroach noted in the home past 3 months Yes No |

34 (46.6) 39 (53.4) |

11 (40.7) 16 (59.3) |

45 (45.0) 55 (55.0) |

OR:1.27 (0.52, 3.10) |

| Mice noted in the home past 3 months Yes No |

35 (47.9) 38 (52.1) |

15 (55.6) 12 (44.4) |

50 (50.0) 50 (50.0) |

OR:0.74 (0.30, 1.79) |

p≤0.01

p≤0.05

Mouse, cat, dog, alternaria alternata, aspergillus fumigatus, oak tree, timothy grass, dermatophagoides farinae and common ragweed IgE sensitizations p>0.10 between High vs. low and moderate SABA fills over past 12 months.

The final stepwise multivariate logistic regression model assessing the impact of select variables on high SABA use contained six independent variables (number of ICS fills, cockroach sensitization, prior ICU asthma admission, receipt of asthma specialty care, child age and income). The results indicated that for every additional ICS fill, a child was 1.4 times more likely to have high SABA fills and a child having a positive cockroach sensitization was almost 7 times more likely to have high SABA fills while controlling for prior ICU asthma admission, receiving asthma specialty care, child age and income (Table 3). The model as a whole explained between 0.28 (Cox and Snell R square) and 0.41 (Nagelkerke R squared) of the variance in high SABA use, and correctly classified 74% of cases. Comparable results, i.e. number of ICS fills and positive cockroach sensitization significantly associated with high SABA fills, were obtained when all variables (number of ICS fills, cockroach sensitization, prior ICU asthma admission, receipt of asthma specialty care, child and caregiver age, income and cotinine level) were entered into the multiple logistic regression model.

Table 3.

Multivariate Regression Modela Predicting High SABA Use (N=70 cases for full model).

| Baseline Characteristic | B (SE) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Inhaled Corticosteroid (ICS) fills over 12 months |

0.36 (0.15) | 1.43 (1.07, 1.93)b |

| Cockroach allergy sensitization Yes No (reference) |

1.94 ().85) |

6.97 (1.32, 36.70)b |

| ICU admission ever Yes No (reference) |

1.41 (0.77) |

4.08 (0.90, 18.52) |

| Asthma Special Care last 2 years Yes No (reference) |

1.45 (0.80) |

4.28 (0.89, 20.58) |

| Child Age 6-12 years 3-5 years (reference) |

−1.50 (0.88) |

0.22 (0.04, 1.26) |

| Income 0-$19,000 (reference) $20,000-$39,000 >$40,000 |

1.18 (0.83) 0.74 (0.99) |

3.27 (0.64, 16.73) 2.09 (0.30, 14.54) |

Forward stepwise regression. Selection entry criteria of p=0.35 and exclusion criteria of p>0.30. Variables excluded were caregiver age, child gender and baseline cotinine level.

p<0.05

Cox & Snell R square = 0.28, Nagelkerke R square = 0.41 Hosmer and Lemeshow Test for Model : Chi square =11.2, df=8, p=0.19

Discussion

Our data indicate that increased inhaled corticosteroid use was significantly associated with high SABA use, indicating high SABA users received some exposure to anti-inflammatory medication. Perhaps treating acute symptoms with SABA medication may be a reminder or motivator for filling a controller medication or that some caregivers believe that acute exacerbations require treatment with SABA and ICS medications(11) or is their asthma action plan for the “yellow zone”. Alternatively, the dosage of anti-inflammatory coverage may be insufficient to decrease bronchial inflammation and a step-up in therapy may have been indicated but not achieved.

Moreover, increased ICS use with high SABA use may indicate inadequate inhaler technique, i.e. insufficient drug delivery of both medications. Monitoring inhaler technique is an important component of pharmacological management of asthma.30 National asthma guidelines recommend a minimum of two non-urgent asthma clinic visits per 12 months and/or consider referral to an asthma specialist for children with persistent or poorly controlled asthma to include monitoring of inhaler device technique.13 Our data show that only 54% of all participants reported a routine asthma visit with their PCP over the past 3 months, yet had at least one ED asthma visit over the same time period. Further, only 20% of these children reported receiving any asthma specialty care. These PCP visits may have resulted in missed opportunities for guideline based practice to (1) identify high SABA use, (2) assess inhaler device technique, (3) adjust dosage of anti-inflammatory medication and (4) refer children with more severe asthma to an asthma specialist.

Since many asthma exacerbations in children are preceded by exposure to environmental triggers,31 we examined exposures to common indoor allergens and SHS for association with high SABA use to understand their potential impact on SABA overuse. Almost half of all families reported exposure to cockroach and/or mouse, posing a high allergen burden on these children and consistent with the increased prevalence of American cockroach sensitization among Thai children with asthma.32 Positive cockroach sensitization was associated with almost a seven fold risk of high SABA use suggesting that the combination of sensitization and exposure to cockroaches may be a key contributor to asthma morbidity in inner-city children per prior reports.33 Because only one-third of children had received prior allergy testing, most caregivers may be unaware of their child’s sensitization to cockroach and the increased risk for symptoms with exposure. Prevention of symptoms in children with cockroach sensitivity requires exposure to the lowest achievable level, often difficult to achieve for inner-city children residing in multi-unit dwellings.34 This inability to adequately remediate rodent and pest exposures may have contributed to the high morbidity noted in this group of children. Additionally, tailoring home environmental control interventions based on the child’s positive sensitizations may be easier to implement rather than a more comprehensive non-targeted intervention. If cockroaches are present in the child’s home, abatement measures including integrated pest management are recommended.34 Further, subcutaneous cockroach immunotherapy has been shown to be effective in adult pilot studies.35

SABA overuse is associated with higher healthcare utilization.15 A 5-fold higher rate of hospitalization within the past 3 months and almost a 3-fold higher rate of having a prior ICU admission in children with high SABA use was noted when compared to children with low to moderate SABA use. Parent report of daily SABA medication has been associated with very poor asthma control.36 SABA overuse may in part be due to parental misunderstanding or nonadherence and/or inadequate or inappropriate controller stepwise treatment prescribing by health care providers.36 Although short and long-acting beta agonists provide bronchodilation and relieve asthma symptoms, none of the inhaled beta agonists modify the underlying inflammatory process in the lungs.37 It has been suggested that the development of a tolerance to B2-agonists may occur particularly with increasing bronchoconstriction 38 and may explain the cause of asthma deaths outside the hospital in patients who fail to respond to SABA medications as emergency treatment in the home 38 and high prior ICU admission rate. Alternatively, half of caregivers of the high SABA users reported their child’s asthma was controlled indicating a high proportion of caregivers perceived their child’s asthma was controlled despite excessive SABA use. Caregiver definition of well controlled asthma may be based on the availability and response to SABA rather than recognition of symptom severity. Tolerance to SABA medication can be reversed with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), yet low ICS adherence is known to exist in minority inner-city populations as reported in our results. 5,4,11, 39

Lack of association between SHS exposure and high SABA use was surprising, but consistent with prior reports in a comparable sample of inner-city children.(10) Despite parental awareness that SHS exacerbates asthma, 40-67% of inner-city children with asthma reside in a household with at least one smoker.10, 27 Our high rate of SHS exposure (54%) is consistent with multiple inner-city asthma studies.10,22,26 Avoidance of SHS exposures is a key component of national and international guidelines for management of childhood asthma.13 Unlike our prior studies, the caregiver was not the predominant household smoker and she/he may be unable to institute a total home smoking ban without cooperation from all household members. Anecdotally, several children resided in households owned by a grandparent who smoked cigarettes. This may result in the caregiver choosing between continued SHS exposure or seeking alternative housing when resources are scarce. Additionally, prior studies indicate that many caregivers have a misperception that limiting smoking to certain areas of the house (e.g. basement or bathroom) will sufficiently decrease SHS exposure to their children and are unaware of the ubiquitous penetration of SHS in the home.23

Several clinical implications can be drawn from this study. The use of biomarkers to identify potential sensitizations to environmental allergens can be used to target specific home remediation interventions. For example, knowledge of positive cockroach sensitization without dust mite sensitization can result in a targeted pest management intervention rather than a costly comprehensive intervention. Providers should consider routine cotinine screening for children identified with uncontrolled asthma. Moreover, identification of high SABA users may prompt primary care and ED providers to observe inhaler technique and perform stepwise controller therapy adjustments to achieve and maintain well controlled asthma. If providers are not confident about instituting stepwise therapy, referral to specialty care should be considered to identify co-morbidities, obtain allergy testing and individualize environmental control recommendations and receipt of appropriate guideline based therapy.

There are potential limitations associated with this study. Use of pharmacy claims data for SABA fills is not a direct measure of SABA use as there may be loss and/or sharing of canisters dispensed. High SABA fills may reflect family sharing of medications and may have resulted in an overestimation of SABA canisters dispensed. Further, generalizability of the results is limited in that we purposely recruited children with more severe or uncontrolled asthma for our study in order to maximize our ability to detect a difference in asthma morbidity and healthcare utilization with our intervention. Thus, our sample of children may have more uncontrolled asthma than the general pediatric asthma population.

In conclusion, one goal of guideline based asthma therapy is to minimize the need for SABA medications, yet we observed overuse of SABA medications with reported concomitant controller medication use. One contributor to SABA overuse may be unknown sensitization to common allergens, with positive sensitization to cockroach allergen among the most risky. The results of this study support monitoring of SABA use, evaluation of allergen sensitization and exposure, screening for SHS exposure and appropriate prescribing and use of controller medications to improve asthma control in inner-city children with asthma.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (NIH), with the grant number R01 NR013486. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov with number NCT01981564. This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by Grant Number UL1 TR 000424-06 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH. We thank Cassia Lewis Land and Cheyenne McCray for their review of the manuscript.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (NIH), (R01 NR013486) and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by Grant Number UL1 TR 000424-06 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT01981564..

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma Prevalence, heath care use, and mortality: United States: 2005-2009. National Health Stat Report. 2011;12(32):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ. Status of Childhood Asthma in the United States, 1908-2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123(Supp 3):S131–S145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crocker D, Brown C, Moolenaar R, et al. Racial and Ethnic disparities in asthma medication usage and health-care utilization. Chest. 2009;136(4):1063–1071. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollinger ME, Mudd KE, Boldt A, et al. Prescription fill patterns in underserved children with asthma receiving subspecialty care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013 Sep;111(3):185–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz T, Sturm T, Matte T, et al. Medication use among children with asthma in East Harlem. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):1188–1193. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega An, Gergen PJ, Paltiel AD, et al. Impact of site of care, race, and Hispanic ethnicity on medication use for childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akinbami LJ, LaFleur BJ, Schoendorf KC. Racial and income disparities in childhood asthma in the United States. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(5):382–387. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0382:raidic>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores G, Snowden-Bridon C, Torres S, Perez R, et al. Urban minority children with asthma: substantial morbidity, compromised quality and access to specialists, and the importance of poverty and specialty care. J Asthma. 2009;46:392–398. doi: 10.1080/02770900802712971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart KA, Higgins PC, McLaughlin CG, et al. Differences in prevalence, treatment and outcomes of asthma among a diverse population of children with equal access to care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(8):720–726. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butz AM, Halterman JS, Bellin M, et al. Factors Associated with Second Hand Smoke Exposure in Young Inner-City Children with Asthma. J Asthma. 2011a;48(5):449–459. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.576742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butz A, Thompson RE, Tsoukleris M, et al. Seasonal Patterns of Controller and Rescue Medications Dispensed in Underserved Children with Asthma. J Asthma. 2008;45(9):800–806. doi: 10.1080/02770900802290697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Shulruff R, et al. Self-reported physician practices for children with asthma: are national guidelines followed? Pediatrics. 106(suppl):886–896. 200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.USDHHS National Asthma Education Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. 2007 NIH Publication No. 07-4051. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paris J, Peterson EI, Wells K, et al. Relationship between recent short-acting beta-agonist use and subsequent asthma exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:482–487. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanford RH, Shah MB, D'Souza AO, et al. Short-acting B-agonist use and its ability to predict future asthma-related outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheehan WJ, Sheehan MD, Rangsithienchal PA, et al. Pest and allergen exposure and abatement in inner-city asthma: A Work Group Report of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Indoor Allergy/Air Pollution Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahluwalia SK, Peng RD, Breysse PN, et al. Mouse allergen is the major allergen of public health relevance in Baltimore City. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(4):830–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine . Clearing the Air: Asthma and Indoor Air Exposures. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsui EC. Environmental exposures and asthma morbidity in children living in urban neighborhoods. Allergy. 2014;69:553–558. doi: 10.1111/all.12361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banda E, Persky V, Chisum G, et al. Exposure to home and school environmental triggers and asthma morbidity in Chicago inner-city children. Pediatr Allergy Immunolo. 2013;24:734–741. doi: 10.1111/pai.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruchalla RS, Pongracic J, Plaut M, et al. Inner-city Asthma Study: relationship among sensitivity, allergen exposure, and asthma morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(3):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halterman JS, Borrelli B, Tremblay P, et al. Screening for environmental tobacco smoke exposure among inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1277–1283. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butz A, Breysse P, Rand CS, et al. Household Smoking Behavior and Indoor Air Quality of Urban Children with Asthma. Maternal and Child Health J. 2011;15(4):460–468. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0606-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke H, Leonardi-Bee J, Hasnim A, Pine-abata H, Chen Y, Cook DG, Britton JR, McKeever TM. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):735–744. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang JE, Dozor AJ, Holbrook JT, Mougey E, Krishnan S, Sweeten S, Wise RA, Teague WG, Wei CY, Shade D, Lima JJ. Biologic mechanisms of environmental tobacco smoke in children with poorly controlled asthma: results from a multicenter clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;1(2):172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar R, Curtis LM, Khiani S, et al. A community–based study of tobacco smoke exposure among inner-city children with asthma in Chicago. J Allergy Clinical Immunology. 2008;122(4):754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarville M, Sohn MW, Oh E, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and asthma exacerbations and severity: the difference between measured and reported exposure. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2013;98(7):510–514. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stempel DA, McLaughlin TP, Stanford RH. Treatment patterns for pediatric asthma prior to and after emergency department events. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40(4):310–315. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.IBM Corp . Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funston W, Higgins B. Improving the management of asthma in adults in primary care. Practitioner. 2014;258(1776):15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulet LP, Cartier A, Thomson NC, et al. Asthma and increases in nonallergic bronchial responsiveness from seasonal pollen exposure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;71:399–406. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuenyongviwat A, Koonrangsesomboon D, Sangsupawanich P. Recent 5-year trends of asthma severity and allergen sensitization among children in southern Thailand. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31(3):242–246. doi: 10.12932/AP0289.31.3.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bassirpour G, Zoratti E. Cockroach allergy and allergen-specific immunotherapy in asthma: potential and pitfalls. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:535–541. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Portnoy J, Chew GL, Phipatanakul W, Williams PB, Grimes C, Kennedy K, Matsui EC, Miller JD, et al. Environmental assessment and exposure reduction of cockroaches: a practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(4):802–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.061. e1-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood RA, Toigas A, Wildfire J, Visness CM, Matsui EC, Gruchalla R, Hershey G, Liu AH, O'Connor GT, Pongracic JA, Zoratti E, Little F, Granada M, Kennedy S, Durham SR, Shamji MH, Busse WW. Development of cockroach immunotherapy by the Inner-city Asthma Consortium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schatz M, Nakahiro R, Crawford W, et al. Asthma quality-of-care markers using administrative data. Chest. 2005;128:1968–1973. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mcivor RA, Pizzichini E, Turner MO, et al. Potential masking effects of salmeterol on airway inflammation in asthma. Am J. Resp Crit Care Med. 1998;158:924–930. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9802069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wraight JM, Herbison GP, Cowan JO, et al. Tolerance to the acute bronchodilator effects of beta-agonist with increasing degrees of bronchoconstriction. Respirology. 2001;6:A48. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sloan CD, Gebretsadik T, Pingsheng W, et al. Reactive versus practice patterns of inhaled corticosteroid use. Ann Am Thoracic Society. 2013;10(2):131–134. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201209-076BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]