Abstract

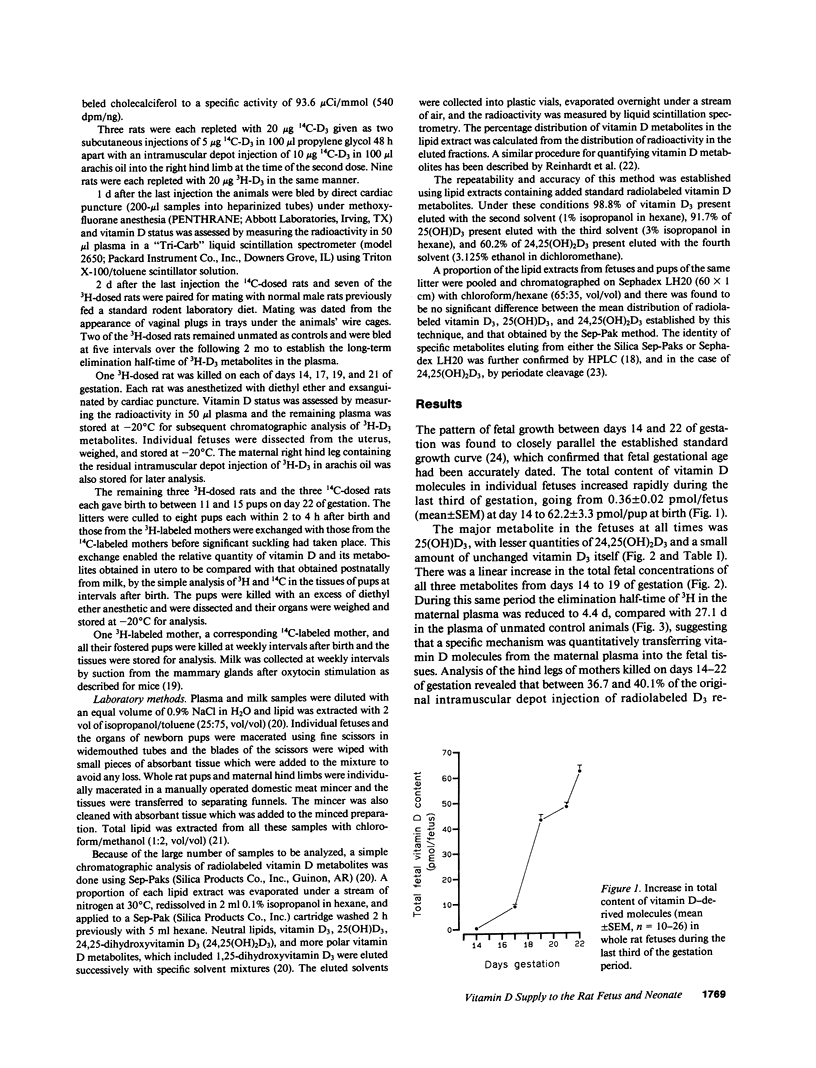

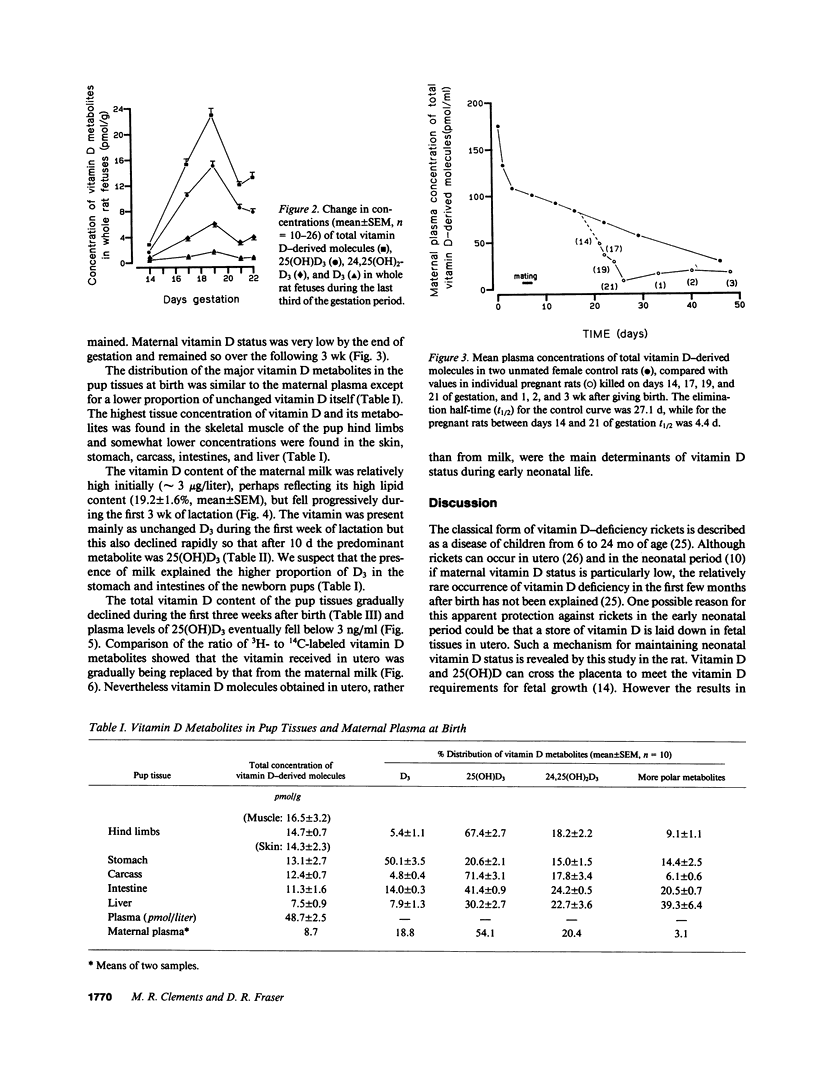

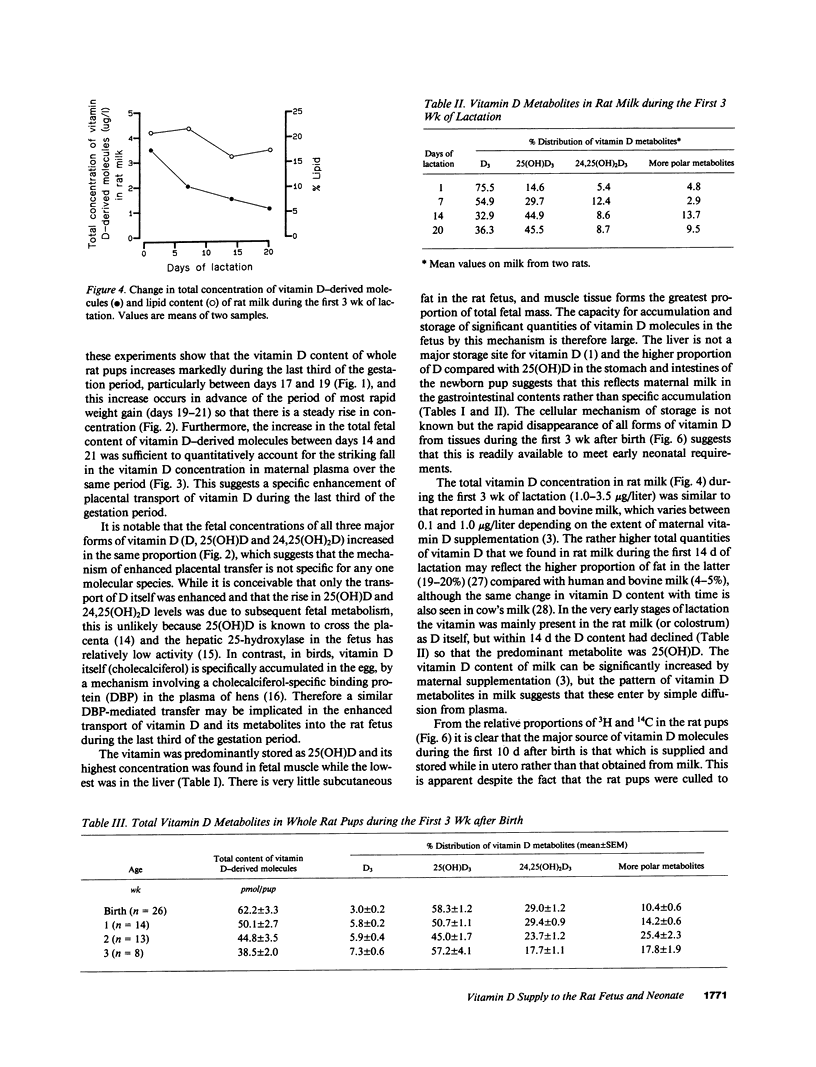

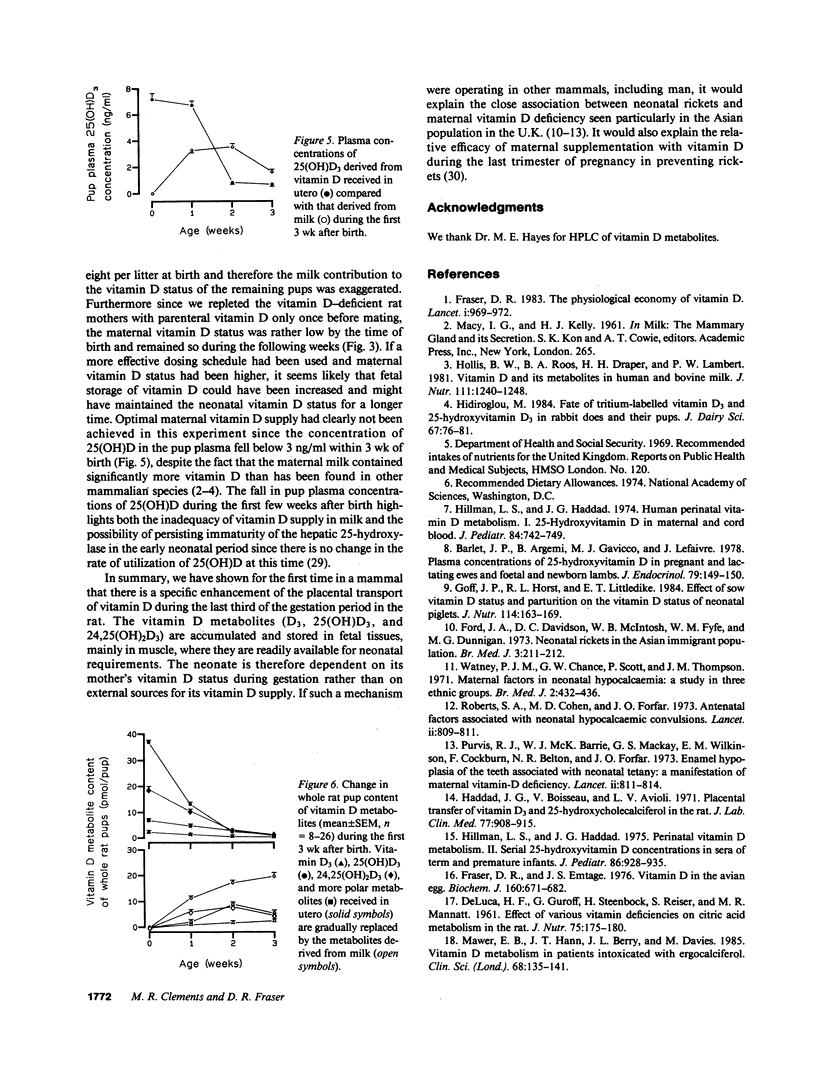

The prevention of neonatal rickets by oral supplementation with vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) has tended to obscure our ignorance of the natural mechanism by which young mammals receive an adequate supply of vitamin D. To investigate the possibility of specific intrauterine transfer and storage of vitamin D in fetal tissues, vitamin D-deficient female rats were given depot injections of 3H- or 14C-labeled vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) before mating and the 3H-labeled animals were killed at stages during the last third of gestation. Analysis of lipid extracts from whole fetuses revealed a linear increase in the concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and D3 itself between days 14 and 19 of gestation. During this period the elimination half-time of 3H-labeled molecules in maternal plasma fell from 27.1 to 4.4 d, suggesting that a specific mechanism was transferring vitamin D molecules into the fetuses. The vitamin was stored predominantly as 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, with the highest concentrations in fetal muscle. Immediately after birth, pups from 3H- and 14C-labeled mothers were exchanged and later killed after 1-3 wk of suckling. Analysis of total lipid extracts for 3H and 14C content determined the relative contributions of vitamin D supplied before birth via the placenta and after birth in the maternal milk. The vitamin D content of the rat milk was relatively high, between 1.0 and 3.5 micrograms/liter. Nevertheless, the supply of vitamin D in utero, rather than from milk, was the main determinant of vitamin D status in early neonatal life. This is the first indication in a mammal of a specific transfer mechanism that allows the fetus to accumulate vitamin D from the mother during the last third of gestation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BLIGH E. G., DYER W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959 Aug;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlet J. P., Argemi B., Davicco M. J., Lefaivre J. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in pregnant and lactating ewes and foetal and newborn lambs. J Endocrinol. 1978 Oct;79(1):149–150. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0790149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LUCA H. F., GUROFF G., STEENBOCK H., REISER S., MANNATT M. R. Effect of various vitamin deficiencies on citric acid metabolism in the rat. J Nutr. 1961 Oct;75:175–180. doi: 10.1093/jn/75.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J. A., Davidson D. C., McIntosh W. B., Fyfe W. M., Dunnigan M. G. Neonatal rickets in Asian immigrant population. Br Med J. 1973 Jul 28;3(5873):211–212. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5873.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D. R., Emtage J. S. Vitamin D in the avian egg. Its molecular identity and mechanism of incorporation into yolk. Biochem J. 1976 Dec 15;160(3):671–682. doi: 10.1042/bj1600671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D. R. The physiological economy of vitamin D. Lancet. 1983 Apr 30;1(8331):969–972. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff J. P., Horst R. L., Littledike E. T. Effect of sow vitamin D status at parturition on the vitamin D status of neonatal piglets. J Nutr. 1984 Jan;114(1):163–169. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad J. G., Jr, Boisseau V., Avioli L. V. Placental transfer of vitamin D3 and 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in the rat. J Lab Clin Med. 1971 Jun;77(6):908–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidiroglou M. Fate of tritium-labeled vitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in rabbit does and their pups. J Dairy Sci. 1984 Jan;67(1):76–81. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman L. S., Haddad J. G. Human perinatal vitamin D metabolism. I. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in maternal and cord blood. J Pediatr. 1974 May;84(5):742–749. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(74)80024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman L. S., Haddad J. G. Perinatal vitamin D metabolism. II. Serial 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in sera of term and premature infants. J Pediatr. 1975 Jun;86(6):928–935. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann F. A., Sawatzki G., Schmitt H., Kubanek B. A milker for mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1982 Aug;32(4):387–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M. F., Schnoes H. K., DeLuca H. F., Gray R. W., Boyle I. T., Suda T. Isolation and identification of 24,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, a metabolite of vitamin D made in the kidney. Biochemistry. 1972 Nov 7;11(23):4251–4255. doi: 10.1021/bi00773a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis B. W., Roos B. A., Draper H. H., Lambert P. W. Vitamin D and its metabolites in human and bovine milk. J Nutr. 1981 Jul;111(7):1240–1248. doi: 10.1093/jn/111.7.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet E., Gügi B., Brunelle P., Hénocq A., Basuyau J. P., Lemeur H. Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy: a controlled trial of two methods. Obstet Gynecol. 1986 Sep;68(3):300–304. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198609000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawer E. B., Hann J. T., Berry J. L., Davies M. Vitamin D metabolism in patients intoxicated with ergocalciferol. Clin Sci (Lond) 1985 Feb;68(2):135–141. doi: 10.1042/cs0680135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn M., Haddad J. G. Postnatal fall and rise of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the rat*. J Lab Clin Med. 1975 Jul;86(1):32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano T., Yokoshima K., Kobayashi T. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of vitamin D3 in bovine colostrum, early and later milk. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1984 Oct;30(5):431–439. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.30.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis R. J., Barrie W. J., MacKay G. S., Wilkinson E. M., Cockburn F., Belton N. R. Enamel hypoplasia of the teeth associated with neonatal tetany: a manifestation of maternal vitamin-D deficiency. Lancet. 1973 Oct 13;2(7833):811–814. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90857-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redhwi A. A., Anderson D. C., Smith G. N. A simple method for the isolation of vitamin D metabolites from plasma extracts. Steroids. 1982 Feb;39(2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(82)90082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt T. A., Horst R. L., Orf J. W., Hollis B. W. A microassay for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D not requiring high performance liquid chromatography: application to clinical studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984 Jan;58(1):91–98. doi: 10.1210/jcem-58-1-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. A., Cohen M. D., Forfar J. O. Antenatal factors associated with neonatal hypocalcaemic convulsions. Lancet. 1973 Oct 13;2(7833):809–811. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. B., Coward W. A. Dietary supplementation increases milk output in the rat. Br J Nutr. 1985 Jan;53(1):1–9. doi: 10.1079/bjn19850003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. G., Hill L. F. True fetal rickets. Br J Radiol. 1974 Oct;47(562):732–734. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-47-562-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watney P. J., Chance G. W., Scott P., Thompson J. M. Maternal factors in neonatal hypocalcaemia: a study in three ethnic groups. Br Med J. 1971 May 22;2(5759):432–436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5759.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]