Abstract

Background

Beta-2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) agonists are critical treatments for asthma. However, receptor desensitization can lead to loss of therapeutic effects. While desensitization to repeated use of β2 agonists is well studied, Type-2 inflammation could also impact β2AR function.

Objective

To evaluate the impact of the Type-2 cytokine, IL-13, on β2AR desensitization in human airway epithelial cells (HAECs) and determine whether 15-Lipoxygenase-1 (15LO1) binding with phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein-1 (PEBP1) contributes to desensitization through release of G-protein Receptor Kinase-2 (GRK2).

Methods

HAECs in air-liquid-interface (ALI) culture with/without IL-13 (48 hrs) or isoproterenol (ISO) (30 min) pretreatment were stimulated with ISO (10min). cAMP was measured by ELISA and β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation by Western Blot. siRNA was utilized for 15LO1 knockdown. Interactions of GRK2, PEBP1 and 15LO1 were detected by Immunoprecipitation/Western Blot and immunofluorescence. HAECs and airway tissue from controls and asthmatics were evaluated for I5LO1, PEBP1 and GRK2.

Results

Pretreatment with ISO or IL-13 decreased ISO-induced cAMP generation compared to ISO for 10 min alone, paralleled by increases in β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation. GRK2 associated with PEBP1 after 10 min of ISO in association with low pGRK2 levels. In contrast, in the presence of IL-13+ISO (10 min), binding of GRK2 to PEBP1 decreased, while 15LO1 binding and pGRK2 increased. 15LO1 knockdown restored ISO-induced cAMP generation. These findings were recapitulated in freshly brushed HAEC from asthmatic cells and tissue.

Conclusion

IL-13 treatment of HAECs leads to β2AR desensitization which involves 15LO1/PEBP1 interactions to free GRK2 and allow it to phosphorylate (and desensitize) β2ARs, suggesting beneficial effects of β2 agonists could be blunted in Type-2 associated asthma.

Keywords: IL-13, cAMP, Phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein-1, 15-lipoxygenase-1, β2AR, GRK2, asthma

Introduction

Beta-2-agonist drugs, central to obstructive airway disease management, work through activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), specifically the beta-2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR). This receptor is present on many cells including airway epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Activation of β2ARs on airway smooth muscle leads to muscle relaxation and bronchodilation, while acute epithelial cell effects include enhanced ciliary beat and mucus clearance.1 Chronic exposure of a GPCR to its ligand leads to receptor desensitization via receptor phosphorylation and internalization. Indeed, continuous β2-agonist use results in loss of bronchodilator and bronchoprotective effects2–7 and deterioration of asthma control.8,9 Following ligand stimulation and arrestin binding, β2ARs are internalized. They can then be recycled to the surface following removal of ligand or more permanently made inaccessible in states of chronic stimulation10,11. GPCR kinases (GRKs), specifically GRK2, play important roles in mediating β2AR desensitization.12,13 GRK2 phosphorylates the receptor, allowing arrestins to bind, effectively blocking receptor interaction and activation of heterotrimeric G proteins.14

Interestingly, GRK2 also interacts with the multifunctional protein phosphatidyl-ethanolamine binding protein 1 (PEBP1). Normally, PEBP1 binds to and inactivates Raf-1 (an activator of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathways), thereby serving as an endogenous inhibitor of those pathways.15–19 Under inflammatory conditions which phosphorylate PEBP1, conformational changes in PEBP1 induce its dissociation from Raf-1 allowing PEBP1 to bind GRK220,21. This binding to PEBP1 prevents GRK2 from phosphorylating the β2AR allowing ongoing receptor activation.

Recent studies showed that 15 lipoxygenase-1 (15LO1), an enzyme induced by the Type-2/Th2 cytokine IL-13 in epithelial cells, also binds to PEBP1. 15LO1 is upregulated in asthma in association with IL-4/-13/”Type-2” inflammation, ERK activation and increases in the mucin, MUC5AC.22,23 Importantly, similar to GRK2, enhanced 15LO1 expresssion by IL-13 displaces Raf-1 from PEBP1 allowing it to bind 15LO1, an association recapitulated in asthmatic epithelial cells in vivo. In vitro, this binding enhances ERK activation and MUC5AC expression.

We therefore hypothesized that under “Type-2“ conditions, as evidenced by high levels of 15LO1 seen in ~50% of asthma patients, 15LO1 would preferentially bind to PEBP1 while displacing (and freeing up) GRK2 to be phosphorylated. This phosphorylated GRK2 would phosphorylate and desensitize the β2AR, decreasing cyclic adenosine 3, 5-monophosphate (cAMP) response to β-agonists. To address this hypothesis, HAECs were evaluated for their cAMP response to β2AR stimulation, as well as their levels of phosphorylated β2AR, in the presence and absence of IL-13 induced 15LO1. The role of IL-13 induced 15LO1 was evaluated by measuring the binding of 15LO1 and GRK2 to PEBP1 in vitro. The subsequent effect of 15LO1 knockdown on β2AR desensitization/cAMP activation was then addressed. These in vitro experiments were compared to in vivo findings in airway epithelial cells and tissues from asthmatic and control patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Asthmatic participants met American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria for asthma24 and were recruited as part of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program, NIH AI-40600 or the Electrophilic Fatty Acid Derivatives in Asthma studies25. Mild-Moderate asthmatics had an FEV1 of ≥60% predicted on short acting β-agonists (SABA) only or on low-moderate dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) (<880 mcg/day fluticasone propionate or equivalent) +SABA. Severe asthma was defined by the American Thoracic Society 2000 definition, consisting of 1 or 2 major criteria (high-dose ICS and/or frequent use of oral CS) with at least 2 of 7 minor criteria.26 Healthy controls (HCs) had no history of respiratory disease or recent respiratory infection and normal lung function. No subject smoked within the last year or >5 pack years. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and all participants gave informed consent.

Bronchoscopy with epithelial airway brushings

Bronchoscopy with epithelial brushing was performed as previously described27,28. Per protocol, all participants including HCs received 2.5 mg nebulized albuterol within 15–45 min of the procedure.

Primary Human Airway Epithelial Cell (HAEC) Culture and siRNA Transfection

Primary HAECs were cultured in air liquid interface as previously described28,29,30. siRNA transfection was performed on 70% confluent cells in 12-well transwell plates during submerged culture using Mirus si-QUEST transfection reagent. (See online supplement).

Western Blotting

Cell lysates were run on 4–12% SDS-PAGE gels under reducing conditions as previously described.28

cAMP Assay

Cells were washed with cold PBS, stimulated for 10 minutes with ISO 1 µM, and lysed for cAMP levels using a competitive enzyme-linked immunoassay kit.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed, pre-cleaned with Protein A agarose beads, and incubated with pull-down antibody prior to incubation with Protein A agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates (IPs) were centrifuged and separated on 4–12% SDS/PAGE gels for Western blot using primary antibodies generated from different species from the pull-down antibody. For details, see the online supplement.

Immunofluorescence (IF) and Confocal Microscopy

Tissues were fixed in acetone and embedded in glycol-methacrylate for immunofluorescence (IF) staining as previously described29. For details, see online supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical demographics data were generally normally distributed and analyzed by T-Test; categorical data were analyzed by Chi-square analysis. All subjects were divided into 15LO1 Lo vs Hi on the basis of the median split of the 15LO1 protein expression data in the fresh epithelial cells. Clinical experimental data were not normally distributed, but the majority of fresh epithelial cell data were normalized by natural log transformation and could be analyzed by T-test. Ex vivo Co-IP data were not normally distributed after log transformation and were therefore analyzed non-parametrically with Wilcoxon Rank Sum testing.

In vitro data, including percent/fold changes, were analyzed using linear and non-linear models. All control and stimulated condition values were normally distributed except for IL-13 stimulated pGRK2, while the fold changes were normally distributed using natural log transformation. To test the differences between the control and stimulated groups, the natural log of the fold change was compared to zero using normal approximation for null distribution. Although analytically we used mean and standard deviation (SD) (pβ2AR and pGRK2) or standard error of the mean (SEM) (cAMP) of log transformed data, we reported the results as the geometric mean and geometric co-efficient of variation (CV). Comparisons of fold changes (IL-13 vs ISO30 pretreatment) were performed by T-test Pairwise correlations were performed on normally distributed data. No formal adjustment for multiple testing was applied. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP SAS software (Cary, NC). P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In vitro studies

Subject Demographics

Airway epithelial cells were obtained from a total of 73 subjects, including 15 healthy controls (HC) and 58 asthmatics. In vitro culture studies were performed on HAECs from 5 HCs and 44 asthmatics (Supplemental Table 1). There were no differences in responses by asthma disease state or severity.

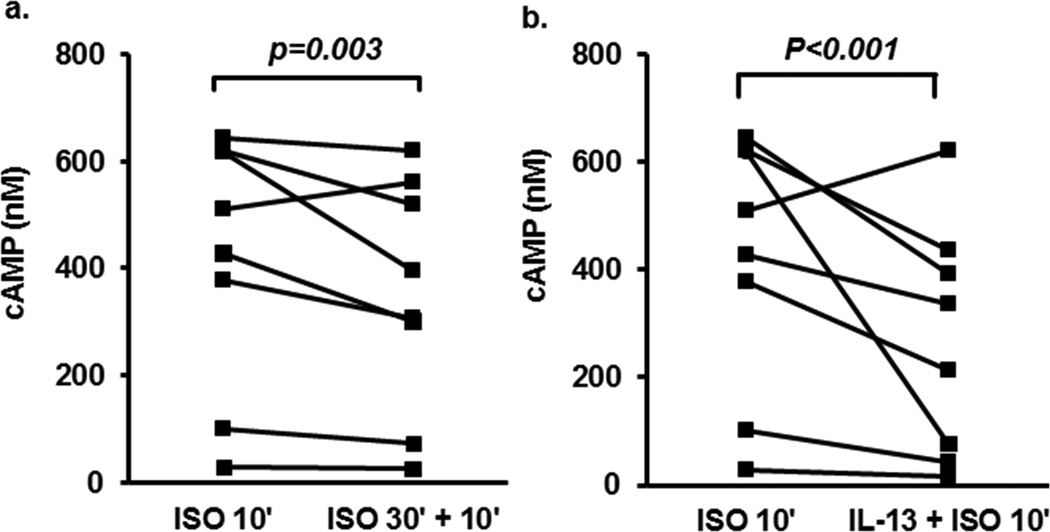

IL-13 decreases cAMP generation in response to Isoproterenol

To determine whether IL-13 impacts β2AR desensitization in HAEC, cAMP generation was evaluated in response to ISO (1 µM for 10 min) in the presence or absence of IL-13 (10 ng/ml) for 48 hours and compared to the cAMP response to a 2nd addition of ISO following 30 minutes of ISO (1µM) pre-treatment, a protocol which reduces cAMP response.31. Stimulation of cells with ISO for 10 min induced a high level of cAMP release (Figure 1). There was a 17% (GCV=12%) decrease in cAMP by ISO pretreatment for 30 min (Figure 1a, p=0.003). IL-13 pretreatment for 48 hrs inhibited cAMP release 46% (GCV=25%) in response to ISO (10 min) (Figure 1b, p<0.001). Although not statistically significant, IL-13 tended to reduce ISO-induced cAMP release to a greater degree than prior ISO treatment (p=0.066, data not shown).

Figure 1.

IL-13 pretreatment decreases cAMP release in response to Isoproterenol stimulation. ALI-cultured primary BAECs were pretreated with either ISO (30 min) or IL-13 (48 hr) followed by stimulation with ISO for 10 min. Cells were harvested for cAMP levels by ELISA. (a). ISO stimulation for 10 min induced high cAMP levels (415±84 SEM)), which were inhibited by ISO (30min) pretreatment (350±77(SEM)). (b). IL-13 pretreatment for 48 hrs inhibited cAMP release induced by ISO for 10min alone (267± 76 (SEM)).

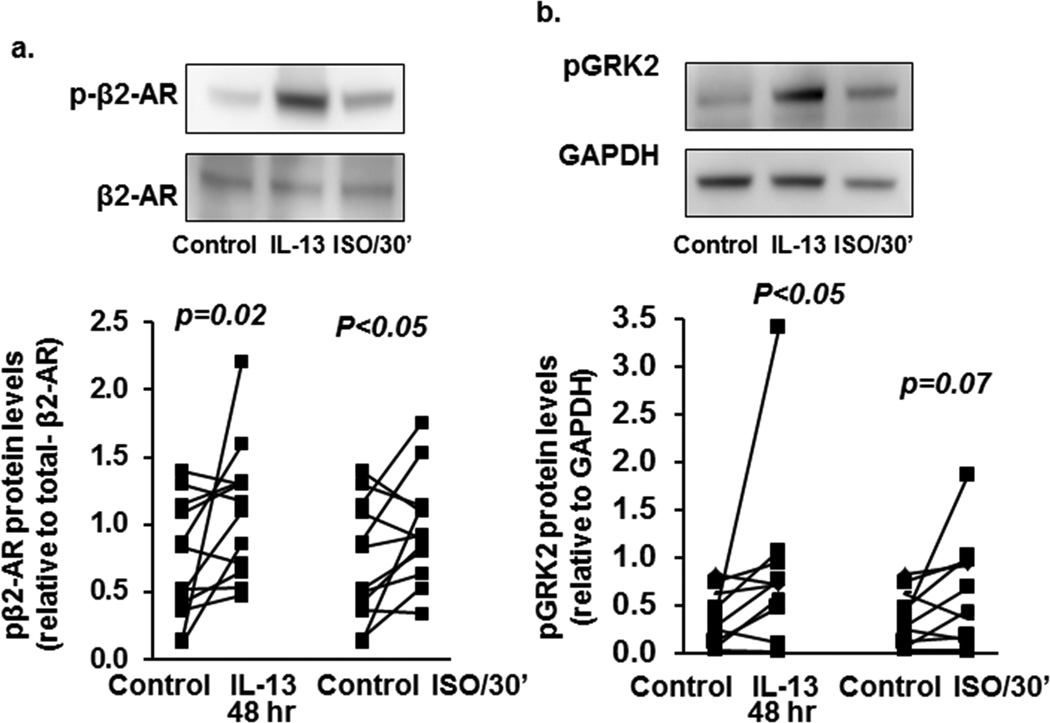

IL-13 and ISO induce phosphorylation of the β2AR and GRK2

As IL-13 pretreatment inhibited cAMP generation in response to ISO, HAECs were treated with either IL-13 (10 ng/ml) for 48 hours or ISO (1 µM) for 30 minutes, β2AR phosphorylation measured and indexed to total β2AR. Both IL-13 and ISO increased pβ2AR as compared to media alone (Figure 2a, 54% (GCV=32%) increase p=0.022, and 45% (GCV=25%) increase, p<0.05 respectively. (Also seen in Supplemental Figure S1a). Similar increases were observed when pβ2AR was normalized to GADPH (p=0.02, Supplemental Figure S1b and d). There were no effects of IL-13 on total β2AR protein expression or membrane translocation. However, IL-13 did increase cytosolic pβ2AR (Supplemental Figures S1b,c and e). Increases in pβ2AR paralleled decreases in cAMP after pretreatment with IL-13 or ISO.

Figure 2.

IL-13 and ISO induce β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation in primary BAECs. ALI-cultured BAECs were stimulated with ISO (30 min) or IL-13 (48 hr). Total protein was harvested for β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation by Western blot and densitometry analysis. (a) Both IL-13 (1.06±0.13) and ISO (1.01±0.13) significantly increased β2AR phosphorylation compared to media alone (0.75±0.11). (b) Both IL-13 (0.88±0.27) and ISO (0.69±0.16) significantly increased GRK2 phosphorylation compared to media alone (0.39±0.08).

Previous studies suggest phosphorylation of GRK2 is required for β2AR phosphorylation and desensitization.32 GRK2 phosphorylation was evaluated in the presence and absence of IL-13 and ISO pretreatment by Western blot. GAPDH was applied as the loading control (See supplemental methods). ISO marginally increased GRK2 phosphorylation by 35% (GCV=18%) (p=0.07) while IL-13 increased pGRK2 by 58% (GCV=20%) (p<0.05) (Figure 2b, Supplemental Figure S2), suggesting IL-13 promotes β2AR phosphorylation and desensitization through a GRK2 mechanism.

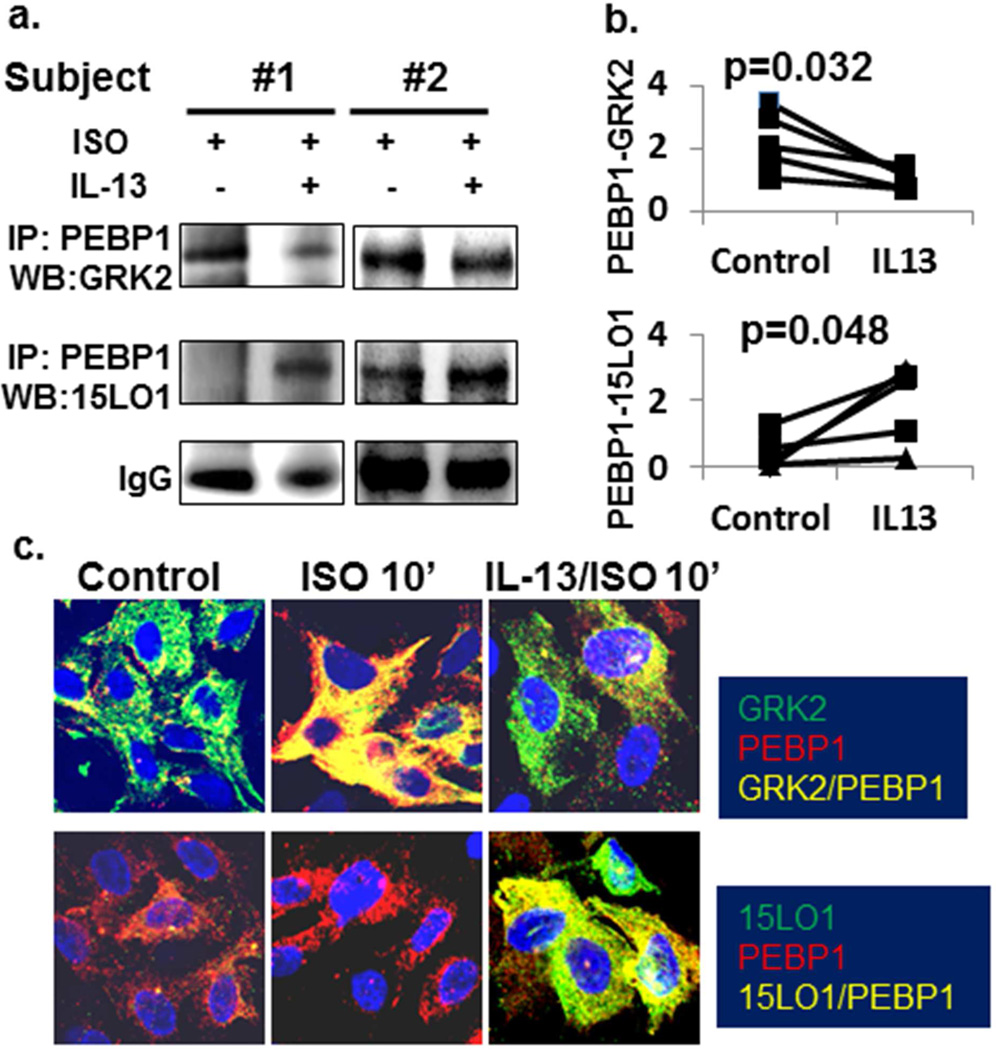

IL-13 suppresses GRK2 binding to PEBP1 in response to ISO in vitro: Potential involvement of 15LO1 in β2AR phosphorylation and desensitization

β2AR activation is regulated by interactions of GRK2 with PEBP1.16,17 Factors which prevent GRK2 binding to PEBP1 will increase GRK2 association with the β2AR complex promoting receptor phosphorylation and desensitization.22 We hypothesized that under IL-13/Type-2 conditions, 15LO1 would displace GRK2 from PEBP1 allowing it to phosphorylate the β2AR. Accordingly, primary HAECs were treated with IL-13+ISO or ISO alone and IP/Western Blot or IF staining performed. As expected, GRK2 bound with PEBP1 in response to ISO (Figure 3a). In contrast, IL-13 (10 ng/ml) pretreatment decreased binding of GRK2 to PEBP1 in response to ISO, compared to ISO alone (Figure 3a and 3b upper panel, p=0.032), while as expected (and in contrast), the binding of PEBP1 with 15LO1 increased (Figure 3b, lower panel p=0.048).

Figure 3.

IL-13 suppresses GRK2 binding to PEBP1 and enhances 15LO1 binding to PEBP1 in response to ISO in vitro. BAECs in the presence or absence of IL-13 (48 hr) were stimulated with ISO for 10 min. Total protein was harvested for Western blot/IP. Cells were also fixed for IF staining. (a) GRK2 bound with PEBP1 in response to ISO while pretreatment with IL-13 markedly decreased binding of GRK2 to PEBP1 and increased 15LO1 binding to PEBP1. (b) Densitometry analysis of Western blot/IP. (C) Confocal analysis showing that ISO treatment increased the colocalization (yellow) of GRK2 (green) with PEBP1 (red) as compared to control. This colocalization was less in the presence of IL-13. In contrast, 15LO1 (green) was highly expressed and colocalized/bound (yellow) to PEBP1 in the presence of IL-13 and not affected by ISO.

Confocal analysis confirmed these studies. ISO (10 min) increased co-localization of GRK2 with PEBP1 compared to control, while in the presence of IL-13, this co-localization was suppressed (Figure 3c upper panel). In contrast, 15LO1 was highly bound to PEBP1 in the presence of IL-13 and not affected by ISO (Figure 3c lower panel). Thus, IL-13-induced 15LO1 competitively binds with PEBP1 lowering GRK2 binding to PEBP1 in vitro.

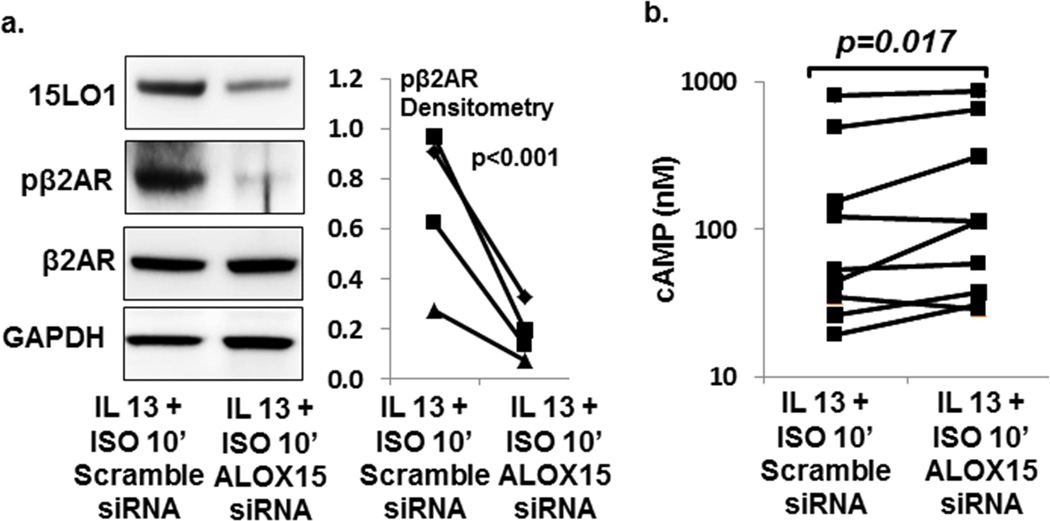

Knockdown of 15LO1 in the presence of IL-13 restores cAMP generation in response to ISO stimulation

To confirm that high 15LO1 levels inhibit cAMP generation, siRNA knockdown of 15LO1 in the presence of IL-13 was performed and cAMP and pβ2AR measured. IL-13 induced 15LO1 protein expression (p=0.013), while ISO (30 min) did not (p=0.4) (Supplemental Figure S3). ALOX15 siRNA knocked down 15LO1 protein by 30–80% (Figure 4a, and Supplemental Figure S4a,b). ALOX15 siRNA transfection also decreased β2AR phosphorylation by 63–86% in the presence of IL-13+ISO (10 min) (Figure 4a, p<0.001). ALOX15 knockdown in IL-13 stimulated cells increased cAMP generation by 34% (GCV=35%) in response to ISO (10 min) compared to scramble siRNA (Figure 4b, p=0.017) and as fold-change compared to scramble fold-change p=0.02 (Supplemental Figure S4c). No changes were observed in total β2AR after ALOX15 siRNA transfection (Figure 4a, and Figure S4a,d). The decrease in β2AR phosphorylation and restoration of cAMP release following ALOX15 knockdown confirmed that 15LO1 desensitizes the β2AR, likely through a GRK2/PEBP1 mechanism.

Figure 4.

ALOX15 siRNA knock-down of 15LO1 expression restored ISO induced cAMP generation in BAECs. ALI-cultured cells transfected with ALOX15 siRNA or scramble siRNA were stimulated with IL-13 for 48 h + ISO 10 min. Total protein was harvested for Western blot and ELISA analysis. Data are presented as the mean of duplicates. (a) ALOX15 siRNA knocked down 15LO1 protein and decreased β2AR phosphorylation induced by IL-13/ISO stimulation. (b) ALOX15 siRNA knock-down restored ISO (10 min) induced cAMP generation in cells treated with IL-13 for 48 hours (244±102 SEM) as compared to scramble siRNA (196±91 SEM).

Ex vivo studies

Subject Demographics

Ex vivo studies of freshly brushed epithelial cells (western blot) were performed on 36 subjects, including 10 HCs and 26 asthmatics (Table 1). Subjects were categorized by 15LO1 phenotype (Lo vs Hi as median split). 15LO1 Hi subjects were more likely to be mild CS-naïve or severe asthmatics, the majority of whom were on oral CSs, and were more likely to be male. There were no differences in FEV1, SABA or LABA use between the 2 phenotypes. However, FeNO was significantly higher in 15LOi-Hi subjects as compared to 15LO1-Lo subjects (p<0.001). Fresh HAECs from 14 subjects were utilized for IP/Western blot (Table 2). In small numbers, there were no differences in 15LO1 Lo vs Hi subjects, except age was higher in the 15LO1 Hi group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects undergoing analysis of fresh epithelial cells (n=36)

| ALL SUBJECTS | 15 LO1 Lo* | 15 LO1 Hi | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 40±12 | 39±1 | 0.8 |

| Sex (% Female) | 82% | 42% | 0.01 |

| Race (C/AA/Other) % | 65/29/6 | 79/19/8 | 0.34 |

| FEV1% Predicted mean±SEM | 88±7 | 77±5 | 0.18 |

| Bronchodilator response (%) mean+SEM | 12±3 | 16±4 | 0.31 |

| Severity¥ (%) | 29/18/29/24 | 26/26/0/47 | 0.03 |

| FeNO (ppb) mean±SEM | 21±3 | 45±7 | 0.007 |

| ASTHMA ONLY (n=26) | |||

| ICS (No/Yes) % | 17/83 | 36/64 | 0.27 |

| LABA (No/Yes) % | 42/58 | 57/43 | 0.43 |

| SABA (puffs/week) Mean±SD | 6±8 | 15±15 | 0.09 |

15 LO1 Lo/Hi calculated as median split of densitometry data for 15 LO1 among all subjects

C=Caucasian, AA=African American, O=other

Severity=HC/Mild no ICS/Mild-Moderate+ICS/Severe

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects for Co-IP analysis (n=14)

| ALL SUBJECTS | 15 LO1 Lo* | 15 LO1 Hi | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 38±4 | 54±4 | 0.01 |

| Sex (% Female) | 38% | 33% | 0.8 |

| Race (C/AA/Other) #% | 86/14/0 | 50/50/0 | 0.14 |

| FEV1% Predicted mean±SEM | 80±7 | 67±9 | 0.3 |

| Bronchodilator response (%) mean+SEM | 7±3 | 5±3 | 0.59 |

| Severity¥ (%) | 37/13/13/37 | 17/17/33/33 | 0.73 |

| FeNO (ppb) mean±SEM | 37±10 | 34±11 | 0.8 |

| ASTHMA ONLY (n=10) | |||

| ICS (No/Yes) % | 20/80 | 20/80 | 1.0 |

| LABA (No/Yes) % | 40/60 | 20/80 | 0.29 |

| SABA (puffs/week) Mean±SD | 10±4 | 6±4 | 0.4 |

15 LO1 Lo/Hi calculated as median split of densitometry data for 15 LO1 among all subjects

C=Caucasian, AA=African American, O=other

Severity=HC/Mild no ICS/Mild-Moderate+ICS/Severe

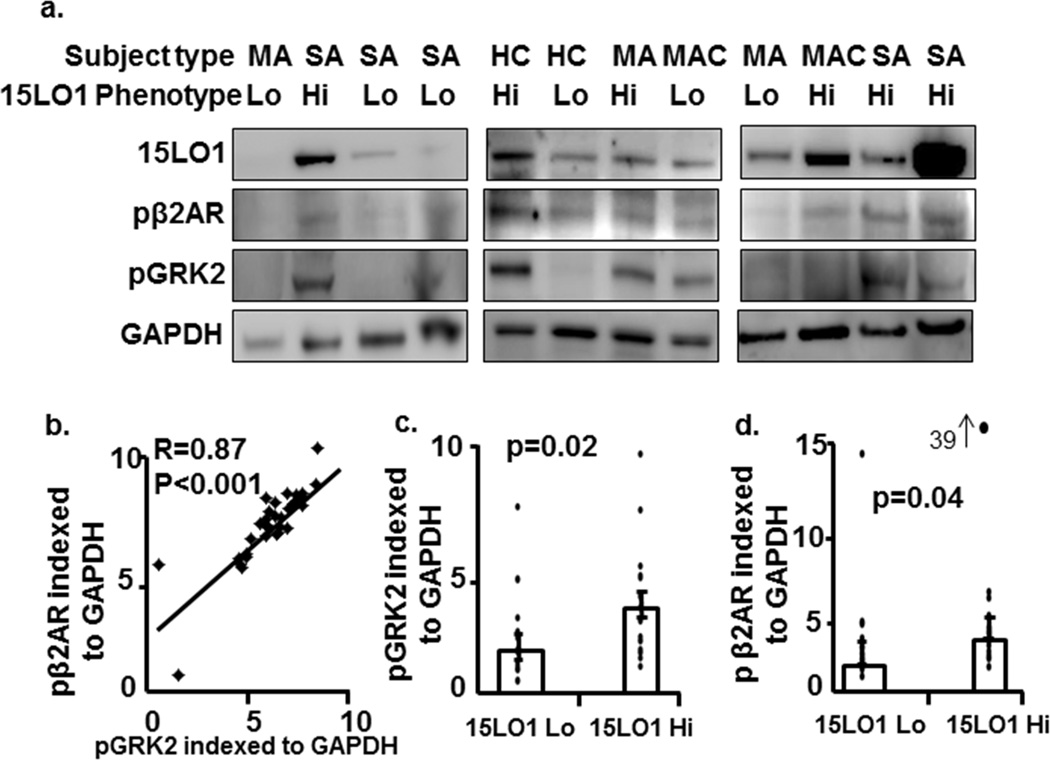

β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation positively correlate with 15LO1 expression in human airway epithelial cells ex vivo (Table 1)

As the in vitro data suggested a relationship of pGRK2 to pβ2AR (and receptor desensitization), the relation of pGRK2 to pβ2AR was evaluated by Western blot ex vivo in freshly brushed airway epithelial cells (see supplemental methods). Although absolute levels varied within subjects, perhaps due to albuterol pretreatment of all participants prior to bronchoscopy, pβ2AR levels strongly correlated with pGRK2 in these cells (Figure 5a and b, n=36, R=0.87, p<0.001). Phosphorylated β2AR and GRK2 levels also positively correlated with 15LO1 expression (r=0.52 and 0.47, p=0.002 and p=0.005 respectively, data not shown). When subjects were categorized into 15LO1 Lo and 15LO1 Hi groups using a median split of 15LO1 protein data, phosphorylated GRK2 and β2AR were significantly higher in the 15LO1 Hi group compared to the 15LO1 Lo group (Figure 5c, p=0.02, and 5d, p=0.04, respectively). No change in total GRK2 and β2AR protein expression was seen across the subjects ex vivo (Supplemental Figure S5).

Figure 5.

β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation positively correlate with 15LO1 expression in primary human airway epithelial cells ex vivo. (a) Total protein from freshly brushed airway epithelial cells was harvested and β2AR and GRK2 phosphorylation measured by Western blot. Densitometry analysis was performed. pβ2AR, pGRK2 and 15LO1 were normalized to GAPDH and reported as arbitrary units. (b) pβ2AR positively correlated with pGRK2. (c) phosphorylated GRK2 and (d) pβ2AR levels in 15LO1-Hi group were higher as compared to 15LO1-Lo group. Abbreviations: HC=Healthy control, MA=mild asthma/no ICS, MAC=mild-moderate+ICS, and SA=Severe Asthma.

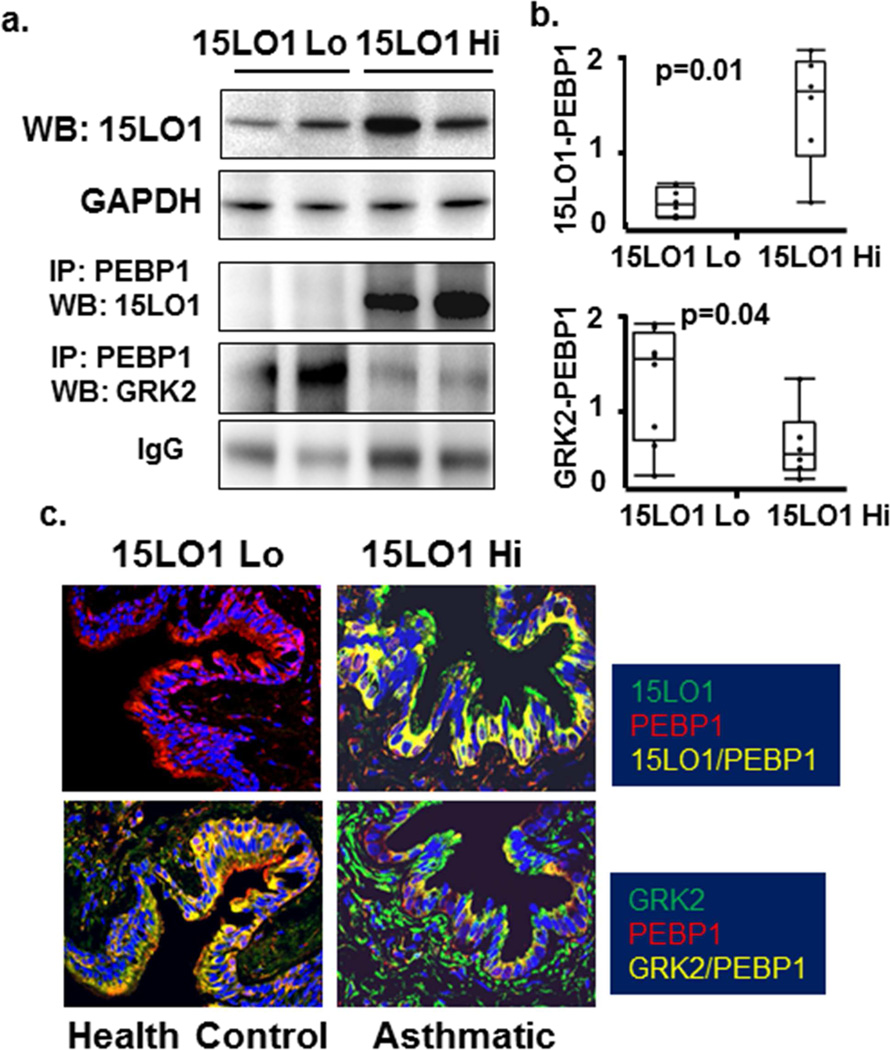

15LO1 binding to PEBP1 is associated with less GRK2 binding to PEBP1 in asthmatic cells and tissue (Table 2)

As in vitro data suggested IL-13 induced 15LO1 competitively binds PEBP1 to decrease its binding to GRK2, this association was also evaluated ex vivo in freshly brushed airway epithelial cells by IP/Western blot. As noted, prior to bronchoscopy all participants received albuterol as a safety measure, which could increase GRK2 binding to PEBP1 in the absence of 15LO1. Although the level of GRK2 binding to PEBP1 varied across the subjects (Figure 6a and b/Supplemental Table S2 for demographics), in general, higher levels of 15LO1 binding to PEBP1 were associated with lower GRK2 binding. These increases in 15LO1 binding to PEBP1 paralleled the 15LO1 levels observed by Western Blot.

Figure 6.

15LO1 binding to PEBP1 is associated with less GRK2 binding to PEBP1 in asthmatic cells and tissue as compared to health controls. Total protein from freshly brushed airway epithelial cells was harvested for Western blot/IP analysis. Lung tissue from asthmatic and healthy control subjects were fixed for Immunofluorescent-confocal microscopy studies. (a) Higher levels of 15LO1 binding to PEBP1 were associated with lower GRK2 binding in freshly brushed epithelial cells. (b) Densitometry analysis of Western blot/IP. (c) Expression 15LO1 and its colocalization with PEBP1 was higher in an asthmatic subject as compared to the control donor lung. In contrast, GRK2 colocalization with PEBP1 in the airway epithelium was lower in the asthmatic subject as compared to a healthy control.

To support this ex vivo observation further, IF-confocal microscopy was performed on lung tissue from 8 asthmatics and 8 HC (subject characteristics in Supplemental Table S2). As expected, 15LO1 co-localization with PEBP1 was higher in most asthmatic subjects compared to HC (Figure 6c, representative image). In contrast, GRK2 co-localization with PEBP1 in the airway epithelium was lower in asthmatic subjects as compared to the HC, consistent with the IP/Western blot, suggesting 15LO1 binding to PEBP1 can increase free/phosphorylated GRK2 which then phosphorylates and desensitizes the β2AR in the presence of IL-13.

Discussion

β2 agonists are indispensible asthma treatments, primarily inducing bronchodilation through effects on smooth muscle.33 However, their effects on epithelial cells to clear mucus are also important.34 This study is the first to observe a clinically meaningful effect of IL-13 to decrease β-agonist responsiveness in primary HAECs and to identify complex interactions between 15LO1, GRK2 and PEBP1 as contributing to this effect. In cultured human HAECs, IL-13 induces GRK2 and β2AR phosphorylation, while promoting 15LO1 expression. Enhanced 15LO1 expression contributes to increases in pGRK2 by competitively binding to PEBP1, freeing GRK2 from its binding to PEBP1. Free GRK2 can then phosphorylate the β2AR, desensitizing it and decreasing downstream activation as measured by lower cAMP production. These in vitro interactions were present in asthmatic epithelial cells and tissue ex vivo. Importantly, siRNA knockdown of 15LO1 restored cAMP generation in response to isoproterenol in vitro. These results strongly suggest that the elevated 15LO1 expression observed in asthma, particularly in relation to Type-2 inflammation, contributes to desensitization of the β2AR in HAECs.

The β2AR belongs to the seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family. β2AR activation enhances adenylate cyclase activity and cAMP synthesis, which promote smooth muscle relaxation in airways and blood vessels, enhance ciliary beating, enhancing mucin clearance.35,36 However, repeated β2AR stimulation leads to receptor desensitization through phosphorylation of GRK2, which promotes phosphorylation and internalization of the β2AR.12,37 This receptor activation/desensitization is complex with different mechanisms involved in different settings, although phosphorylation of β2AR is central to all.34 Although inflammation is likely to play a role in modulating β2AR desensitization, it has not been extensively studied. However, anti-inflammatory drugs like corticosteroids have been reported to reverse or prevent it38, while allergen challenge has been reported to slightly decrease β2AR sensitivity.39

IL-13, a Type-2 cytokine, plays a role in ~50% of asthma.40 IL-13 blockade, alone or in combination with IL-4, through targeted biologic approaches, consistently improves outcomes in asthmatics with evidence for Type-2 inflammation, with some of the most robust improvement seen in FEV1 even when added to ICS/LABA therapy.41,42 This suggests that improvement in FEV1 with these agents (on top of LABA) may be due to an improved effect of the LABA. While some of this effect is likely on airway smooth muscle responses, chronic improvement in FEV1 in more severe asthma likely also involves improved mucus clearance. Interestingly, another recent study suggests that tachyphylactic responses to β2 agonists during exercise challenge may be related to the level of background Type-2-immune processes, as they appear more likely to occur in patients with high FeNO levels (a known IL-4/-13 biomarker)43. Additionally, the β2AR gene is nested in the 5q31 region with the IL-4, 13 and 5 genes suggesting common origins. However, their interactions have not been specifically explored. The results reported here specifically link IL-13 and β2AR function, with the presence of a Type-2/IL-13 environment leading to nearly a 50% reduction in cAMP response to β2 agonist stimulation in primary HAECs. This reduced cAMP response associated with increased GRK2 and β2AR phosphorylation suggests IL-13 promoted β2AR desensitization through a GRK2 mechanism.32

This association of IL-13 induced β2AR desensitization with GRK2 phosphorylation suggested that PEBP1 may be involved, as under certain stimulatory conditions (Protein kinase C activation and acute β2 agonist stimulation) PEBP1 dissociates from Raf-1 and binds with GRK2.16 GRK2 binding to PEBP1 prevents it from phosphorylating the β2AR prolonging receptor activation, and promoting activation of ERK through release of Raf-1 from PEBP1. However, we reported that in addition to GRK2 and Raf-1 binding to PEBP1, the eicosanoid generating enzyme, 15LO1, also binds PEBP1.29 15LO1, a lipoxygenase that generates 15 hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15s-HETE), is upregulated in response to IL-13 stimulation of HAECs and is increased in asthma in relation to Type-2/eosinophilic processes.23,27–29,44 In addition to upregulation of 15LO1 in response to IL-13, stimulation of HAECs with IL-13 promotes binding of 15LO1 to PEBP1, with subsequent release of Raf-1, activation of ERK and increased expression of the airway mucin, MUC5AC.23 Thus, we hypothesized that in the presence of IL-13, 15LO1 would compete with GRK2 for binding to PEBP1, leading to more free GRK2 and greater likelihood for β2AR desensitization (even in the absence of β2 stimulation).

As expected, GRK2 binding to PEBP1 was observed in cells stimulated with ISO for 10 min, supporting an active β2AR manifested by high cAMP expression. More importantly, pretreatment of cells with IL-13 decreased the association of GRK2 with PEBP1, in response to ISO, and in association with increases in 15LO1 binding to PEBP1. This decrease in GRK2 binding to PEBP1 in the presence of IL-13 was associated with increased pGRK2, pβ2AR and decreased cAMP production after ISO. Finally, 15LO1 knockdown prevented its interaction with PEBP1, but promoted binding of GRK2 to PEBP1 which returned production of cAMP post-ISO to near baseline.

To determine the relevance of these interactions to human disease, we evaluated the relationships of GRK2 and 15LO1 with PEBP1 in bronchial epithelial cells from asthmatics and controls obtained by bronchoscopy. As noted, bronchoscopic samples were obtained post-albuterol for safety reasons, which likely also promoted β2AR phosphorylation. Nevertheless, in the ex vivo samples, higher 15LO1 expression was associated with greater pGRK2 and pβ2AR levels. We also evaluated the binding of 15LO1 and GRK2 to PEBP1 in fresh epithelial cells using Co-IP and western blot, as well as confocal microscopy on airway tissue. The Co-IP studies demonstrated a strong inverse relationship of GRK2 binding to PEBP1 when compared to 15LO1 binding. Finally, the same associations were observed using confocal microscopy on asthmatic compared to control tissue. Thus, the in vitro findings were recapitulated ex vivo in human asthmatics.

We report that in the presence of Type-2 inflammation, IL-4/-13 induced 15LO1 binding to PEBP1 interferes with GRK2 binding, desensitizing the β2AR. The associated decrease in cAMP levels is likely to adversely affect mucociliary clearance, such that exogenous administration of β2 agonists, in the presence of Type-2 inflammation, may have little epithelial cell impact, and, in fact, could limit overall improvement in FEV1 in response to treatment. Future in vitro and in vivo studies of ciliary beat are needed to fully address this. However, it is important to note that airway smooth muscle cells, likely the primary target for β2 agonists in asthma, do not express 15LO1. Thus, any effects of IL-13 on β2AR/bronchodilator responses are unlikely to involve this 15LO1/GRK2 mechanism, explaining why we found no relationship between 15LO1 expression and β2 agonist-induced bronchodilator responses in vivo (data not shown). Whether additional effects of β2AR desensitization could be seen in macrophages or eosinophils (each of which express 15LO1) co-stimulated with IL-13 and β2 agonists remains to be determined.

β2AR desensitization likely occurs through many mechanisms. Depending on the stimulation, desensitization can occur through receptor uncoupling, internalization, phosphorylation and other closely related kinase pathways including other GRKs.12,45 Although further studies are needed to confirm whether GRK2/PEBP1 interactions desensitize β2ARs in HAECs, results presented here support the importance of this pathway. However, under Type-2 conditions, interactions of 15LO1 with PEBP1 directly prevent GRK2 from being in an “inactive” state, bound to PEBP1. This preferential binding of 15LO1 with PEBP1 not only leads to a freeing of Raf-1 and sustained activation of ERK, but also allows free GRK2 to phosphorylate the β2AR leading to its desensitization. Intriguingly, a recent study further suggested that free GRK2 could act as a scaffolding protein for ERK, perhaps further augmenting its activation.46 Thus, in the face of IL-13 induced 15LO1, enhanced availability of GRK2 could not only lead to a desensitized β2AR, but also increase the IL-13 induced activation of ERK, all of which could dramatically change epithelial cell function.

Limitations of the study include the small sample sizes and the confounding of β2 agonist use in the ex vivo studies. Additional data are needed to confirm that the IL-13-induced β2AR desensitization observed here has functional impact on ciliary beat and mucociliary clearance both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, due to difficulties with specific antibodies, total GRK2 could not be used as the index for pGRK2 in most samples. However, the correlation between GRK2 and GAPDH were very strong, such that we do not believe the results would have been appreciably changed.

In summary, these results demonstrate a potentially clinically relevant impact of IL-13 on desensitization of the β2AR in HAECs. The mechanism involves an enhanced availability of free GRK2 for phosphorylation due to its displacement from PEBP1 by high levels of IL-13-induced 15LO1. The downstream impact to desensitize the β2AR has implications for epithelial function in asthma and other airway diseases with evidence for Type-2 inflammation, especially when combined with the known effect of 15LO1 to increase MUC5AC through a similar mechanism. Modification of interactions of 15LO1 with PEBP1 could be a novel target for restoring β2AR sensitization in airway diseases.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

IL-13 stimulation desensitizes the β2AR through 15LO1’s competitive inhibition of GRK2 binding to PEBP1

These interactions, observed in vitro and in vivo, could limit the beneficial effects of β2 agonists in the airway epithelium

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH AI-40600-15(SEW); CTSI UL1-RR024153 (SEW), American Heart Association grant 0825556D (JZ), American Lung Association RG-231468-N (JZ).

Abbreviations

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptors

- β2AR

beta-2-adrenergic receptor

- GRK2

G-protein receptor kinase 2

- 15LO1

15-Lipoxygenase-1

- PEBP1

phosphatidyl ethanolamine binding protein 1

- Th2

T helper-2

- ISO

Isoproterenol hydrochloride

- ICS

Inhaled corticosteroids

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinases

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine 3, 5-monophosphate

- HAEC

primary human airway epithelial cell

- FeNO

exhaled nitric oxide

- SABA

short acting β-agonists

- LABA

long acting B2 agonists

- HC

healthy controls

- ALI

Air-liquid interface

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium duodecyl Sulfate-polyacrylimide gel

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- ALOX15

gene name for 15LO1

- IF

immunofluorescence

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lindberg S, Khan R, Runer T. The effects of formoterol, a long-acting beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist, on mucociliary activity. European journal of pharmacology. 1995;285:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00416-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cockcroft DW, Bhagat R, Kalra S, Swystun VA. Inhaled beta 2-agonists and allergen-induced airway responses. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1995;96:1013–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deshpande DA, Penn RB. Targeting G protein-coupled receptor signaling in asthma. Cellular signalling. 2006;18:2105–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhagat R, Kalra S, Swystun VA, Cockcroft DW. Rapid onset of tolerance to the bronchoprotective effect of salmeterol. Chest. 1995;108:1235–1239. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung D, Timmers MC, Zwinderman AH, Bel EH, Dijkman JH, Sterk PJ. Long-term effects of a long-acting beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist, salmeterol, on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with mild asthma. The New England journal of medicine. 1992;327:1198–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210223271703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters SP, Fish JE. Prior use of long-acting beta-agonists: friend or foe in emergency department? The American journal of medicine. 1999;107:283–285. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villaran C, O'Neill SJ, Helbling A, et al. Montelukast versus salmeterol in patients with asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Montelukast/Salmeterol Exercise Study Group. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1999;104:547–553. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sears MR, Taylor DR, Print CG, et al. Regular inhaled beta-agonist treatment bronchial asthma. Lancet. 1990;336:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93098-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel E, Chinchilli VM, Ford JG, et al. Use of regularly scheduled albuterol treatment in asthma: genotype-stratified, randomised, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1505–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krasel C, Bunemann MB, Lorenz K, Lohse MJ. beta-arrestin binding to the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor requires both receptor phosphorylation and receptor activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:9528–9535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. Ligand-regulated internalization and recycling of human beta 2-adrenergic receptors between the plasma membrane and endosomes containing transferrin receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson M. Molecular mechanisms of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2006;117:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.012. quiz 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:455–465. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billington CK, Penn RB. Signaling and regulation of G protein-coupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respiratory research. 2003;4:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Trafficking patterns of beta-arrestin and G protein-coupled receptors determined by the kinetics of beta-arrestin deubiquitination. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:14498–14506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung K, Seitz T, Li S, et al. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature. 1999;401:173–177. doi: 10.1038/43686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeung K, Janosch P, McFerran B, et al. Mechanism of suppression of the Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by the raf kinase inhibitor protein. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:3079–3085. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3079-3085.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbit KC, Trakul N, Eves EM, Diaz B, Marshall M, Rosner MR. Activation of Raf-1 signaling by protein kinase C through a mechanism involving Raf kinase inhibitory protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:13061–13068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slupsky JR, Quitterer U, Weber CK, Gierschik P, Lohse MJ, Rapp UR. Binding of Gbetagamma subunits to cRaf1 downregulates G-protein-coupled receptor signalling. Current biology : CB. 1999;9:971–974. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diviani D, Lattion AL, Larbi N, et al. Effect of different G protein-coupled receptor kinases on phosphorylation and desensitization of the alpha1B-adrenergic receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:5049–5058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenz K, Lohse MJ, Quitterer U. Protein kinase C switches the Raf kinase inhibitor from Raf-1 to GRK-2. Nature. 2003;426:574–579. doi: 10.1038/nature02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Grider JR, Murthy KS. Cross-regulation of VPAC(2) receptor desensitization by M(3) receptors via PKC-mediated phosphorylation of RKIP and inhibition of GRK2. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2007;292:G867–G874. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00326.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, Maskrey B, Balzar S, et al. Interleukin-13-induced MUC5AC is regulated by 15-lipoxygenase 1 pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;179:782–790. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1744OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;171:912–930. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;181:315–323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proceedings of the ATS workshop on refractory asthma: current understanding, recommendations, and unanswered questions. American Thoracic Society. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000;162:2341–2351. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.ats9-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu HW, Balzar S, Seedorf GJ, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta2 induces bronchial epithelial mucin expression in asthma. The American journal of pathology. 2004;165:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trudeau J, Hu H, Chibana K, Chu HW, Westcott JY, Wenzel SE. Selective downregulation of prostaglandin E2-related pathways by the Th2 cytokine IL-13. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2006;117:1446–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao J, O'Donnell VB, Balzar S, St Croix CM, Trudeau JB, Wenzel SE. 15-Lipoxygenase 1 interacts with phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein to regulate MAPK signaling in human airway epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:14246–14251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018075108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenzel SE, Busse WW. Severe asthma: lessons from the Severe Asthma Research Program. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.025. quiz 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penn RB, Pascual RM, Kim YM, et al. Arrestin specificity for G protein-coupled receptors in human airway smooth muscle. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:32648–32656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan G, Shumay E, Malbon CC, Wang H. c-Src tyrosine kinase binds the beta 2-adrenergic receptor via phospho-Tyr-350, phosphorylates G-protein-linked receptor kinase 2, and mediates agonist-induced receptor desensitization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:13240–13247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasilewski NV, Lougheed MD, Fisher JT. Changing face of beta2-adrenergic and muscarinic receptor therapies in asthma. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2014;16:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dowell ML, Lavoie TL, Solway J, Krishnan R. Airway smooth muscle: a potential target for asthma therapy. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2014;20:66–72. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker JK, DeFea KA. Role for beta-arrestin in mediating paradoxical beta2AR and PAR2 signaling in asthma. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2014;16:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nichols HL, Saffeddine M, Theriot BS, et al. beta-Arrestin-2 mediates the proinflammatory effects of proteinase-activated receptor-2 in the airway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:16660–16665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208881109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGraw DW, Liggett SB. Molecular mechanisms of beta2-adrenergic receptor function and regulation. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2005;2:292–296. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-027SR. discussion 311–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan KS, Grove A, McLean A, Gnosspelius Y, Hall IP, Lipworth BJ. Systemic corticosteriod rapidly reverses bronchodilator subsensitivity induced by formoterol in asthmatic patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1997;156:28–35. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9610113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penn RB, Shaver JR, Zangrilli JG, et al. Effects of inflammation and acute beta-agonist inhalation on beta 2-AR signaling in human airways. The American journal of physiology. 1996;271:L601–L608. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.4.L601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wenzel SE, Wang L, Pirozzi G. Dupilumab in persistent asthma. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:1276. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1309809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1088–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonini M, Permaul P, Kulkarni T, et al. Loss of salmeterol bronchoprotection against exercise in relation to ADRB2 Arg16Gly polymorphism and exhaled nitric oxide. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;188:1407–1412. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1323OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chibana K, Trudeau JB, Mustovich AT, et al. IL-13 induced increases in nitrite levels are primarily driven by increases in inducible nitric oxide synthase as compared with effects on arginases in human primary bronchial epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:936–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heijink IH, van den Berge M, Vellenga E, de Monchy JG, Postma DS, Kauffman HF. Altered beta2-adrenergic regulation of T cell activity after allergen challenge in asthma. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;34:1356–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson JD, Pitcher JA. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) is a Rho-activated scaffold protein for the ERK MAP kinase cascade. Cellular signalling. 2013;25:2831–2839. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.