Abstract

Adipose-derived mesenchymal cells (ACs) and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells (BMCs) have been widely used for bone regeneration and can be seeded on a variety of rigid scaffolds. However, to date, a direct comparison of mesenchymal cells (MC) harvested from different tissues from the same donor and cultured in identical osteogenic conditions has not been investigated. Indeed, it is unclear whether marrow-derived or fat-derived MC possess intrinsic differences in bone-forming capabilities, since within-patient comparisons have not been previously done. This study aims at comparing ACs and BMCs from three donors ranging in age from neonatal to adult. Matched cells from each donor were studied in three distinct bioreactor settings, to determine the best method to create a viable osseous engineered construct. Human ACs and BMCs were isolated from each donor, cultured, and seeded on decellularized porcine bone (DCB) constructs. The constructs were then subjected to either static or dynamic (stirring or perfusion) bioreactor culture conditions for 7–21 days. Afterward, the constructs were analyzed for cell adhesion and distribution and osteogenic differentiation. ACs demonstrated higher seeding efficiency than BMCs. However, static and dynamic culture significantly increased BMCs proliferation more than ACs. In all conditions, BMCs demonstrated stronger osteogenic activity as compared with ACs, through higher alkaline phosphatase activity and gene expression for various bony markers. Conversely, ACs expressed more collagen I, which is a nonspecific matrix molecule in most connective tissues. Overall, dynamic bioreactor culture conditions enhanced osteogenic gene expression in both ACs and BMCs. Scaffolds seeded with BMCs in dynamic stirring culture conditions exhibit the greatest osteogenic proliferation and function in vitro, proving that marrow-derived MC have superior bone-forming potential as compared with adipose-derived cells.

Introduction

Autologous bone grafting is currently the gold standard of bone reconstruction due to its inherent compatibility and integration. However, exact three-dimensional replication of missing bone segments is not possible when transplanting bone from a site dissimilar to the recipient area. In addition, the downsides of donor site morbidity and limited sources remain problematic.1 Tissue-engineered bone constructs represent an alternative for reconstruction of defective bone, in which a rigid, yet porous, scaffold material is seeded with osteogenic cells in the setting of bone-forming stimulation.2–4

Mesenchymal cells (MCs) exhibit strong osteogenic differentiation potential and have proved to be ideal cellular seeding sources for tissue-engineered bone constructs. The presence of pro-osteogenic growth factors and culture media promotes osteogenic differentiation and activity. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells (BMCs) have long been used for this purpose but are more difficult to harvest. Adipose-derived mesenchymal cells (ACs) are generating increased interest due to their widespread availability and ease of harvest.5,6 Although ACs can be driven toward osteogenic differentiation, it is not apparent that the activity from adipose-derived cells is equivalent to that of bone marrow-derived cells. Genetic analysis had previously uncovered greater angiogenic, osteogenic, migratory, and neurogenic capacity in BMCs, but enhanced myogenic capacity in ACs.7 Comparison of the osteogenic potential of ACs and BMCs showed higher levels of osteogenic differentiation in BMCs.8 However, a confounding variable in all previous studies is the difference in donor source of ACs and BMCs. The inter-subject variability inevitably influences the evaluation of cellular osteogenic potential due to differences in age, physiologic and hormonal state, and health conditions and gender of the donors.9,10 Therefore, the ideal experimental scenario would assess osteogenic differentiation of MCs obtained from different tissues in the same donor. Then, a direct comparison can be performed to assess ACs and BMCs under the same conditions, with an emphasis on optimized bone formation. Direct comparison of MCs harvested from the same donor, in identical culture settings, will provide insight into the environmental conditions for optimized osteogenic cellular response.

Regardless of the osteogenic cell source, culture conditions, and growth factors, each impacts cell proliferation and function.11 Native osteoblasts and their progenitors within bony matrices are constantly subjected to interstitial fluid perfusion and shear stress.12 Both BMCs and ACs are mechanosensitive and osteogenically responsive to fluid flow.13,14 Davidson et al. designed a perfusion system for explanted rat femur and demonstrated that perfusing flow significantly upregulated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in explants and endochondral bone viability.15 Shear stress, secondary to fluid flow, activates expression of COX-2, ALP, collagen I, osteopontin (OPN), and osteocalcin (OCN) in BMCs from various species.16 The osteogenic capacities of both ACs and BMCs are enhanced when coupled with mechanical loading or stimulation.17,18 Given the benefits of physiologic flow and mechanotransduction on osteogenic cells, we surmise that creating a more dynamic and physiologic culture environment will enhance the osteogenic proliferation and capacity of a bioengineered graft. The success of bioengineered bone grafts can be limited by the inability to maintain cell growth in the innermost aspects of the construct. The creation of a dynamic, biomimetic type culture system has been espoused to mitigate these issues.19 Bioreactors, such as rotational wall, spinner flasks, and perfusing devices, are designed to be more physiologic by enhancing delivery of oxygen and nutrients, as well as by imparting three-dimensional mechanical stimuli to all cells within the construct.20

The purpose of this study is to compare adipose and bone marrow-derived cells from donors ranging in age from 8 months to 32 years when seeded on decellularized porine bone. Porcine and bovine bone substitutes, as well as hydroxyappatite blocks are available for clinical use. Given the previous clinical use, and the relative ease of decellularization, it was permitted to be a representative scaffold for use in our mechanism. Cells were subjected to distinct culture conditions, including both static and two dynamic settings (stirring, perfusion). Cellular characteristics (proliferation, morphology, and alignment) and osteogenic activity were compared to identify the best bioengineered bony construct. We hypothesize that BMCs cultured under dynamic flow conditions will result in increased osteogenic activity and cell viability, which are prerequisites to successful human implantation.

Material and Methods

Decellularized bone scaffold

Cancellous bone punches from fresh porcine ribs (within 12 h after animal sacrifice, from a local slaughterhouse) were collected and rinsed repeatedly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Collected samples were frozen until decellularized, as described next. The cancellous bone samples (cylindrical, diameter=5 mm, length=10 mm) were briefly flushed with high velocity water to remove the bone marrow. The bone samples were then immersed in detergent (2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [American Bioanalytical] and 10 mM Tris [American Bioanalytical]) and shaken at room temperature for 12 h, followed by sequential washes in methanol, chloroform, and ethanol (each for 10 min). A 0.25% trypsin solution (Invitrogen) was then added, and the samples were digested at 37°C for 20 min. Afterward, deionized water was replaced and the samples were rinsed with sonication in an ultrasound cleaner for 5 min. The entire decellularization procedure was repeated until residual bone marrow was completely removed and trabecular bone was turned. Thereafter, the samples were immersed in an enzyme solution (50 U/mL DNAse [Roche Applied Science], 1 U/mL RNAse [Roche Applied Science], and 10 mM Tris) for 3 h at 37°C, to completely remove cellular material. The scaffolds were then rinsed with deionized water and lyophilized before use. For the characterization of scaffolds, samples were examined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and micro-computed tomography (micro-CT). Samples were then processed for histological staining.

Donors and cell culture

All human tissues that were used in these studies were from tissue samples that were meant for discarding. These tissues were de-identified for patient information except for donor age and sex. Because these tissues were discarded and anonymous they do not fall under human subjects research. The extra donor bone grafts came from cases of alveolar cleft repair—iliac crest cancellous bone harvested for placement at the alveolus for unification in cleft patients. The extra fat came from similar situations, where fat grafting was performed and injected into the lip scars of these patients. All hMSCs were characterized by flow cytometry. According to our previous studies, cells from younger donors have higher proliferative potentials and maintain longer telomere length during in vitro culture compared with cells from elderly donors.10 Thus, we obtained tissue from donors aged 8 months (male), 11 years (female), and 32 years (male).

ACs isolation

Lipoaspirate was obtained from abdominal fat with small fat harvest cannulas with a 10 cc syringe under manual suction. The donor sites were prepared using a small amount of lidocaine with epinephrine in all cases. The ACs were isolated and cultured as previously reported.10 Lipoaspirates were rinsed repeatedly with PBS and digested with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, low glucose; Gibco) containing 0.15% collagenase I (Worthington) for 60 min at 37°C. The stromal vascular fraction was collected by centrifugation, then filtered through a 40 μm strainer, and cultured in complete medium consisting of DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Lonza) and antibiotics. The supernatant was replaced after 2 days with fresh complete medium, and the cultures were maintained in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C.

BMCs isolation

Particulate cancellous bone samples were collected from the same clinical donors. These tissues were meant for discarding, were de-identified, and, therefore, did not require IRB approval for the experiments performed herein. The cells inside trabeculae were flushed out with DMEM, then collected, and finally rinsed twice to thrice with DMEM. Lastly, bone marrow cells were collected by centrifuging the samples at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were suspended in DMEM with 10% FBS, plated onto culture dishes, and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 2 days of culture, the medium and nonadherent cells were discarded and fresh medium was changed at 3–4 day intervals. Cultured cells were treated with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) 7–10 days after the initial plating and labeled as passage 1.

Flow cytometry

Cells derived from individual donors were expanded to passage 1 and analyzed using flow cytometry. Cells from each donor were grown to confluency and trypsinized, and 1×106 cells were resuspended with cold fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS) in FACS tubes. Cells were washed twice with cold FACS buffer, and they were incubated for 30 min on ice with the specific conjugated primary antibody and the corresponding isotype control. The immunostained cells were rinsed twice with cold FACS buffer and analyzed on an LSR II Flow Cytometer device (BD Biosciences). The following human antibodies were used: CD44 (FITC), CD73 (PE), CD90 (APC), and CD105 (APC) (eBioscience).

Engineering of cell-scaffold constructs and bioreactor culture conditions

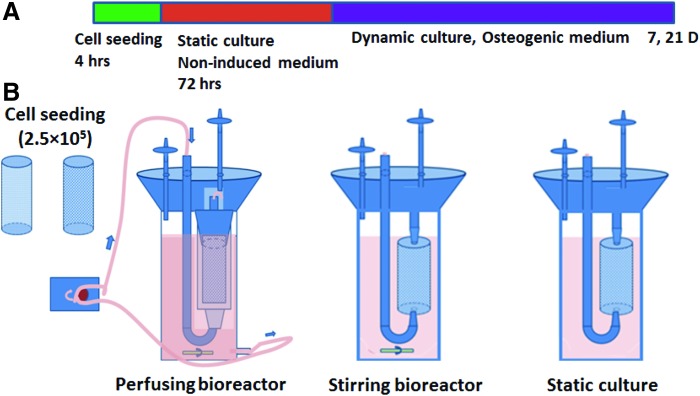

For the bioreactor cultures, cells were expanded in DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics till the second passage. Scaffolds with pore sizes ranging from 250 to 400 μm, as assessed by electron microscopy, were selected for experimentation and were sterilized in 75% ethanol before use. For cell seeding, a cell suspension of 1.0×106 cells per mL was seeded onto scaffolds (250 μL/scaffold) and then the constructs were cultured statically for 3 days to allow seeded cells to attach firmly onto the scaffolds (Fig. 1). Thereafter, cell culture media was replaced with osteogenic medium consisting of DMEM (high glucose), 10% FBS, ascorbic acid (50 mg/L), dexamethasone (1 μmol/L; Sigma), β-sodium glycerophosphate (216 mg/L; Sigma), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). The constructs were divided into three groups: static culture (n=4); stirring bioreactor culture (stirrer was used at 20 rpm) (n=4); and perfusion bioreactor culture (bioreactors supported medium perfusion through the lumen of the constructs) (n=4). In the perfusion bioreactors, constructs were mounted on silicone tubing plugs and inserted into the polypropylene tubes that were connected to the medium flow. A peristaltic pump perfused the lumen of each construct at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The medium was changed every 3–5 days (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematics of the staged bioreactor operation. (A) Culturing procedure for all of the constructs. (B) Three different home-made bioreactors were used: A perfusion bioreactor was driven by peristaltic pump; the constructs were held in by silicon tubing, inserted into the plastic chamber, and underwent medium perfusion. Stirring bioreactors rely on stirring flow driven by a magnetic bar on the bottom. Constructs in static culture had no dynamic fluid flow. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Examination of cell adhesion and proliferation

On days 1, 7, and 21, the constructs were fixed with 10% formalin and stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) for cell nuclei observation. For quantification of cell growth in each scaffold, DNA assays were performed. The samples were digested in proteinase K containing lysate solution according to the manufacturer's instructions (DNAse Blood & Tissue kit; Qiagen). Cell lysates were then centrifuged using QI Shredder columns (Qiagen), and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until quantification. DNA quantification was performed using a Quant-iTTM PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Sample fluorescence was measured (excitation 480 nm, emission 538 nm), and DNA concentration was calculated using a standard curve and standardized using the following formula: cell adherence efficiency=DNA from scaffolds/DNA content (0.25×106)×100.

Histological examination and immunostaining

Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and demineralized with 0.5% EDTA solution for 36 h at room temperature. Afterward, they were frozen into Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature compound, cryosectioned to 8 μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In addition, nondecalcified fresh samples were frozen, cut to 8 μm thick slices, and immunostained for the osteogenic marker OCN. Frozen sections were fixed in 100% ethanol for 10 min, and nonspecific binding was blocked by 30 min of incubation in normal goat serum (5% v/v, 0.1% Triton 100, 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C. Slides were then incubated with the primary anti-OCN antibodies (rabbit anti human; Millipore) for 40 min at 37°C. Slides were rinsed thrice in PBS and then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies (mouse anti rabbit; Abcam) for 30 min at 37°C. Slides were co-stained for nuclei with DAPI (Invitrogen). Negative controls were stained using the same protocol but without primary antibodies.

Scanning electron microscopy

Samples harvested at different time points were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol) for 15 min each, followed by three subsequent dehydrations in 100% ethanol and hexamethyldisilazane until completely dry. Samples were then mounted on aluminum stubs, gold sputtered, and imaged using an XL 30 SEM (Philips).

ALP activity

ALP activity was quantified in constructs cultured for 7 and 21 days. Four-millimeter segments from samples were cut, minced, and lysed using RIPA lysate reagent (containing proteinase inhibitors). Then, the solution was centrifuged at 10,800 g at 4°C for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. The ALP activities of the cells were determined by a spectrophotometric end-point assay that determined the conversion of colorless p-nitrophenyl phosphate to colored p-nitrophenol. In a 96-well plate, 30 μL sample, 70 μL 2-amino-2-methyl-propanol buffer, and 100 μL p-nitrophenyl phosphate (4 mg/mL) were added to each well. Samples were incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 100 μL of 1 M NaOH per well. ALP concentration was measured by absorbance at excitation/emission of 405/600 nm using a BioTek Synergy-MX multiplate reader. Standards were prepared from p-nitrophenol (concentration range: 0–100 μg/mL). All of the ALP concentrations were normalized with DNA content, and technical duplicates were used for each biological sample (n=3).

Quantitative examination of osteogenic gene expression

The mRNA levels of osteogenic markers (RUNX-2, OCN, OPN/bone sialoprotein I, and collagen type I alpha I [Col I]) in cells from different groups were estimated using real-time PCR (RT-PCR) (Bio-rad CFX). Total cellular RNA was extracted from cells in constructs from all groups at different time points using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Then, cDNA was obtained using the Omniscript® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The protocol of quantitative RT-PCR was performed using cDNA as the template in a 25 μL reaction mixture containing iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and a specific primer pair of each cDNA according to published sequences (Table 1). Each reaction was repeated twice, and the threshold cycle average was used for data analysis (Manager software; Bio-Rad CFX). Relative expression was quantified using the ΔΔCt method, and target genes were normalized against GAPDH. The cells cultured in dishes without osteogenic induction served as internal controls (noninduced cells). All the samples were run in triplicate to minimize the sample-to-sample variation.

Table 1.

Sequence of Gene Primer for Real-Time PCR

| Marker | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Human GAPDH |

Forward AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAAC |

| Reverse GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA | |

| Human RUNX-2 |

Forward CCGTCTTCACAAATCCTCCCC |

| Reverse CCCGAGGTCCATCTACTGTAAC | |

| Human osteocalcin (OCN) |

Forward GGACTGTGACGAGTTGGCTG |

| Reverse CCGTAGAAGCGCCGATAGG | |

| Human osteopontin (OPN) |

Forward CTCCATTGACTCGAACGACTC |

| Reverse CAGGTCTGCGAAACTTCTTAGAT | |

| Human collagen-I (COL-I) |

Forward TGACGAGACCAAGAACTG |

| Reverse CCATCCAAACCACTGAAACC |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Micro-CT analysis and calcium quantification

To visualize calcium deposition in the constructs, samples were analyzed using micro-CT (Scanco μCT-35 instrument [5 uM resolution]; Scanco). In addition, samples were processed for Alizarin red staining using standard methods. After staining, the amount of matrix mineralization was determined by dissolving the cell-bound alizarin red S in 10% acetic acid and by quantifying spectrophotometrically at 415 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Each assay was performed on each donor separately, the results were averaged together for final analysis, and the data were reported as mean±standard deviation. Analyses of variance were performed using Sigma Plot software from Systat Software, Inc. followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison tests to establish statistical significance between experimental groups at the p<0.05 (*) level.

Results

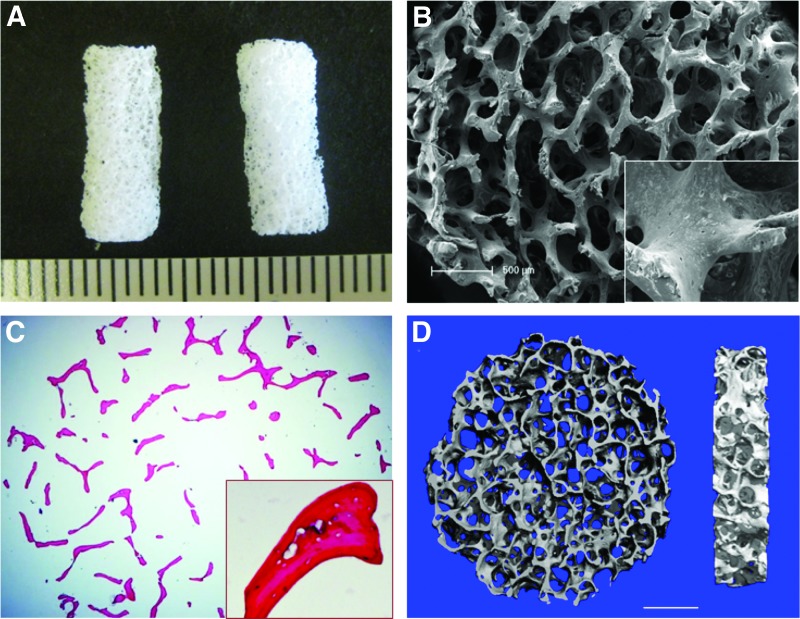

Characterization of decellularized bone

The decellularized bone (DCB) had a ceramic white appearance and a highly porous morphology after lyophilization (Fig. 2A, B). Our protocol efficiently removed cells from cancellous bone matrices. H&E staining of trabecular matrices showed empty lacunae, which were originally occupied by osteocytes (Fig. 2C). SEM images showed a highly porous and interconnected structure after decellularization. Higher magnification of images also showed empty lacunae (Fig. 2B), which confirmed the efficacy of the decellularization protocol. Using micro-CT, we found that pore size ranged from 250 to 400 μm, and the porosity reached 91.1%±2.3% (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Characterization of decellularized bone (DCB). (A) Gross appearance of cylindrical DCB scaffold. (B) Representative scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of DCB show a highly interconnected and porous structure. The lacuna were empty after decellularization (inset). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of DCB shows complete removal of cells in matrices, and (D) micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT) demonstrates that the porosity of DCB is 91.10%±2.31% and pore sizes ranging from 250 to 400 μm (n=3), scale bar=1 mm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

ACs adhere more efficiently to decellularized bone matrix than BMCs

ACs and BMCs from the same donor had similar morphologies that were fibroblast like under phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 3A, B). Surface protein expression of adherent MCs from all groups was examined by flow cytometry (Fig. 3C, D) for MC markers CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105. MC surface protein expression was highly expressed in all of the adherent cells (>90%), which signified a high MC isolation rate from donors. However, the percentage of cells expressing CD44 or CD105 was statistically higher in adipose-derived cells than in bone marrow-derived cells for our three donors (p<0.05). This indicated that the surface markers of MCs vary between different tissue sources.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of adipose-derived mesenchymal cells (ACs) and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells (BMCs) from the same donors (n=3). (A, B) Examination cellular morphology for ACs under a phase-contrast microscope at the first passage (10×). (C, D) Examination of mesenchymal cells (MCs) surface marker expression, including CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105, by flow cytometry at the first cell passage from different groups, and percentage of positively stained cells from three different donors were shown in (E, * means p<0.05). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

DAPI and SEM micrographs showed that BMCs and ACs attached and spread well in all DCB scaffolds at 24 h after cell seeding (Fig. 4A–D). Furthermore, DNA quantification of the constructs indicated that ACs adhered more efficiently than BMCs to the DCB scaffold (Fig. 4E). DNA quantification confirmed significantly higher cellularity in ACs-seeded scaffolds than the BMC constructs (p<0.01) at 24 h.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of cell attachment and cell seeding efficiency for constructs cultured at 24 h after cell seeding. SEM micrographs show cell spreading and flattening in both ACs (A) and BMCs (B) on the surface of trabeculae, scale bar=50 μm. DAPI staining shows more ACs (C) distributed in pores of scaffold than BMCs (D), scale bar=100 μm (E) DNA quantification shows that ACs were seeded with a higher efficiency than BMCs; values are mean±standard error, *p<0.05. Analysis was performed in triplicate, n=3. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Dynamic bioreactor culture conditions promote the cellularity of constructs

At 7 and 21 days, H&E staining showed cellular distribution and tissue growth throughout the culture process (Figs. 5 and 6). In most cases, perfusion bioreactors allowed the highest construct cellularity for both ACs and BMCs during the first 7 days, while stirring bioreactors allowed the highest cellularity of constructs after 21 days of incubation. By day 7 of culture in the perfusion bioreactor, cells began to cover the porous surface; whereas in the static and stirring culture groups, most of the cells sparsely attached to the interior of the scaffolds (Fig. 5a–l). In contrast, perfusion bioreactors allowed even cellular distribution and continuous cell layers in the scaffolds. Multilayers of cells were observed in both AC and BMC constructs that were perfused (Fig. 5 m–r). In stirring bioreactors at day 21 (Fig. 6g–l), both AC and BMC constructs exhibited high cellularity in the scaffolds with cells not only covering the decellularized bone matrix but also filling the pores. In contrast, fewer ACs and BMCs accumulated throughout the scaffold in static cultures (Fig. 6a–f). Perfusion bioreactors seeded with either ACs or BMCs and assayed at day 21 revealed a reduction in proliferation capacity when compared with the stirring bioreactors. The reduction in cellular proliferation capacity between the two conditions was apparent by decreased visible cellular coverage on the bone scaffolds cultured in the perfusion bioreactor as compared with the larger amount of cellular coverage present in the stirring bioreactors (Fig. 6m–r, 21 days).

FIG. 5.

Construct tissue formation after 7 days of culture. H&E staining of constructs was presented as lower magnification (a, d, g, j, m, p scale bar=500 μm) and higher magnification (b, e, h, k, n, q scale bar=200 μm). DAPI staining for cell nuclei was also shown for each construct (c, f, i, l, o, r scale bar=50 μm). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

FIG. 6.

Construct tissue formation after 21 days of culture. H&E staining of constructs was presented as lower magnification (a, d, g, j, m, p scale bar=500 μm) and higher magnification (b, e, h, k, n, q scale bar=200 μm). DAPI staining for cell nuclei was also shown for each construct (c, f, i, l, o, r scale bar=50 μm). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

SEM images confirmed the earlier observations. The images of constructs cultured for 7 days demonstrated that static and stirring bioreactors supported a sub-confluent cell growth, with more ACs distributed in the interior of scaffolds in each group (Fig. 7A-a, b, d, e). In contrast, perfusion bioreactors supported confluent layers of cells in the scaffold pores for both ACs and BMCs constructs on day 7, and cells manifested a spindle-like morphology on DCB scaffolds (Fig. 7A-c, f). DNA assays showed that the cellular content of AC constructs was higher than that of BMCs constructs when cultured in either static bioreactors (23.7±5.1 vs 14.8±1.7 μg/scaffold, p<0.05) or stirring bioreactors (25.6±3.8 vs 17.8±2.9 μg/scaffold, p<0.05) (Fig. 7C). However, perfusion bioreactors greatly improved BMCs proliferation and no significant difference was detected between ACs and BMCs (28.4±4.7 vs 31.1±5.2 μg/scaffold, p=0.5). On day 21, both ACs and BMCs appeared to fill the pores of scaffolds in stirring bioreactors (Fig. 7B-h, k). In contrast, cells in static culture only showed a slight increase in proliferation (Fig. 7B-g, j).

FIG. 7.

Microstructure of constructs and DNA quantification for evaluation of cell proliferation. (A) SEM micrographs for ACs constructs (a–c) and BMCs constructs (d–f) after 7 days in culture. (B) SEM micrographs for ACs constructs (g–i) and BMCs constructs (j–l) after 21 days in culture. Scale bar=100 μm. (C) DNA quantification for constructs cultured for 7 days. (D) DNA quantification for constructs cultured for 21 days, indicating that both ACs and BMCs cultured with stirring bioreactors have the highest cellularization among all groups. Values represent mean±standard error, *p<0.05. Analysis was performed in triplicate, n=3.

Likewise, ACs in perfusion bioreactors appeared less numerous (Fig. 7B-i, l), and this was further confirmed by DNA quantification. In perfusion bioreactors, cell accumulation was not as extensive as that in stirring bioreactors at 21 days. DNA content in ACs and BMCs constructs were in the same range (57.4±11.6 vs 64.6±6.1 μg/scaffold, p=0.4). The DNA contents were significantly lower than counterparts in stirring bioreactors (p<0.05). These data show that cellular dynamics, particularly the ability of these cells to proliferate and survive, can potentially contribute to the bioreactor condition in which the cells were grown. These data demonstrate that the stirring bioreactors had a greater efficiency in allowing for the seeded cells, either ACs or BMCs, to proliferate when compared with either the static or the perfusion bioreactors.

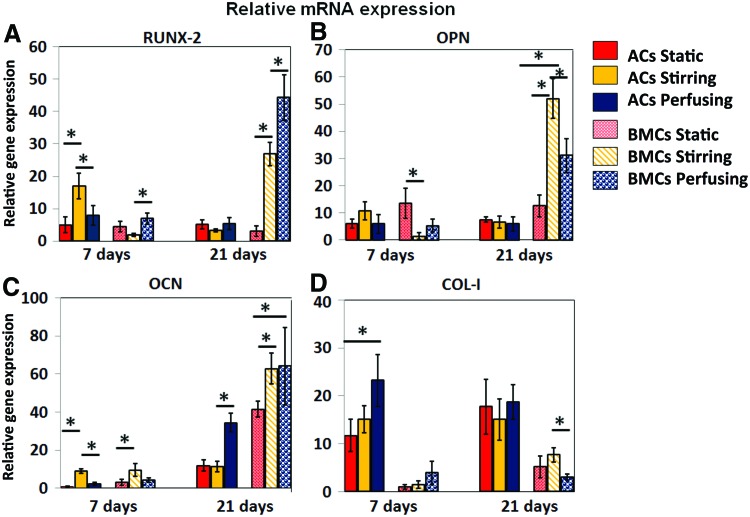

Osteogenic gene expression

The relative expression of RUNX-2, OCN, OPN/bone sialoprotein I, and collagen type I alpha I (Col I) was determined using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with primers and probes that were specific for each osteogenic marker gene (Fig. 8). On the seventh day, ACs expressed higher RUNX-2 in stirring bioreactors than other groups; however, that trend did not continue to day 21 (F=1.95, p=0.22). In contrast, BMCs had lower RUNX-2 expression than ACs on day 7, whereas dynamic culture contributed to the increase of RUNX-2 expression by BMCs at day 21 (p<0.01) (Fig. 8A). OPN is an extracellular structural protein and is an important organic component of bone. On day 7, there were few significant differences among all ACs and BMCs groups for OPN expression. Dynamic culture and longer osteogenic induction did not increase expression of OPN in ACs over time, whereas dynamic culture helped BMCs increase OPN expression by day 21. The stirring bioreactor appeared to be more beneficial to OPN expression with BMCs (p<0.05) (Fig. 8B). In addition, BMCs appeared more sensitive to osteogenic induction than ACs in vitro with overall higher levels of OCN expression at all time points, which were enhanced by dynamic culture. Dynamic culture caused variant OCN expression among groups. At day 7, stirring bioreactors contributed to higher expression than other culturing styles in both ACs and BMCs (p<0.05) (Fig. 8C). Perfusion culture slowly but continuously promoted OCN expression in ACs and BMCs, thus resulting in the highest expression value by day 21. The most prevalent organic component of bone, collagen type I (COL-I), was more highly expressed in ACs (p<0.01) than in BMCs (Fig. 8D). However, COL-I is not specific to bone formation, and higher expression of this gene in ACs is not necessarily indicative of more bony tissue formation in vitro. Our data indicate that stirring bioreactors allow for a greater amount of bone-specific marker gene expression, specifically OCN, from both the BMCs and the ACs when compared with the static and perfusion bioreactor conditions. While OCN is upregulated in both cell types in the stirring bioreactors, BMCs respond more favorably to this condition, as is shown by a statistically greater amount of OCN transcript present in the stirring cultures containing BMCs than in those containing ACs.

FIG. 8.

The relative gene expression of osteogenic markers measured by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The data shown represent the mean±SD (n=3) *p<0.05. (A) RUNX-2 gene expression, ACs in stirring culture, and BMCs in perfusion culture express more RUNX-2 after 7 days in culture; while BMCs in perfusion culture express more at day 21. (B) Osteopontin (OPN) gene expression, BMCs in static culture express more in 7 days; while BMCs in stirring culture express more at day 21. (C) OCN gene expression, ACs and BMCs in stirring culture express more at day 7; while ACs and BMCs in perfusion culture express more at day 21. (D) COL-I gene expression, ACs in perfusion culture express more in 7 days; while BMCs in stirring culture express more at day 21. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

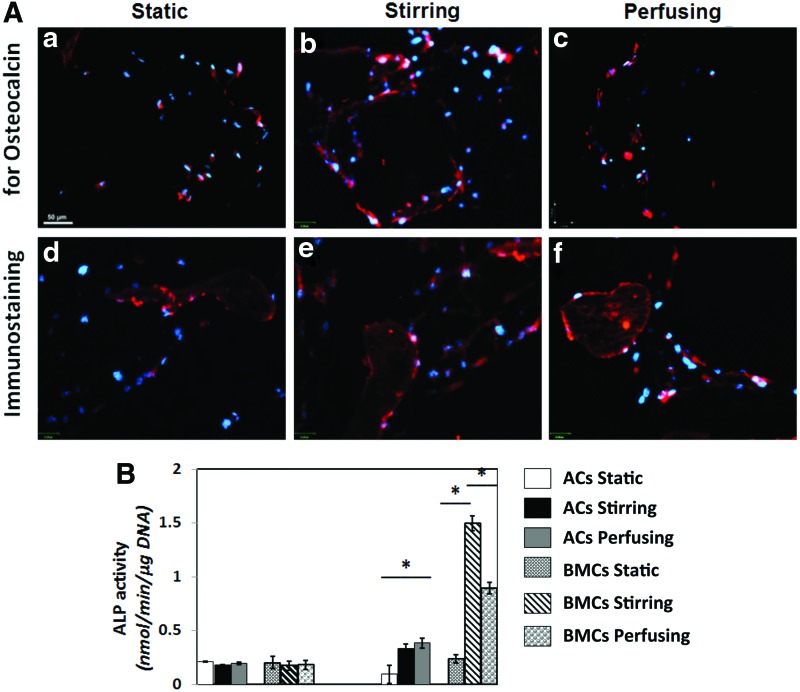

Immunostaining for OCN and ALP activity

OCN is synthesized and secreted exclusively by late-stage osteoblastic cells, and it is thus regarded a marker of mature osteoblasts.14. Immunofluorescence demonstrated expression of OCN in all 21-day constructs (Fig. 9A-a–f). Positively stained cells were distributed predominantly on the outer surfaces of scaffolds in the static group and throughout the scaffolds in stirring and perfusion groups. A higher proportion of cells from stirred bioreactor cultures positively expressed OCN protein, indicating a positive effect of dynamic culture on overall bony marker expression.

FIG. 9.

Immunofluorescence staining for osteocalcin (OCN) (A) in ACs constructs (a–c) and BMCs constructs (d–f) from different bioreactors. (scale bar=50 μm). (B) Measurement of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity ACs in perfusion culture and BMCs in stirring culture have more ALP activity at day 21. The value was presented as mean±standard deviation, *p<0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

ALP enzymatic activity, a marker for early osteogenesis, precedes mineralization of newly formed bone. ALP activity assays revealed that enzyme activity did not vary in a statistically significant manner between the two cell types and various culturing conditions on day 7 (Fig. 9B). In contrast, on day 21, both AC and BMC constructs cultured dynamically had significantly higher enzyme activity than their statically cultured counterparts (p<0.01). In addition, BMC constructs cultured in both stirred and perfusion bioreactors had higher enzymatic activity than all of the AC constructs, and stirred bioreactors had the highest ALP activity among all of the groups for BMCs (p<0.05).

Calcium deposition

Micro-CT was used to evaluate the formation of calcium nodules in the engineered bone constructs (Fig. 10A-a–f). Qualitatively, calcium deposition appeared denser in BMC constructs cultured in stirred bioreactors than in other conditions. It is important to note that since all of the scaffolds were demineralized before cell seeding, all calcium nodule formation occurred de novo during culture. From the Alizarin Red assay, the average calcium content of AC and BMC constructs was similar: 1.1±0.1 versus 1.0±0.1 (p=0.9). In contrast, stirred bioreactors exhibited the highest calcium formation for BMCs constructs (1.9±0.1), and AC constructs in stirred bioreactors also showed higher calcium content (1.3±0.1) than other AC groups (p<0.05).

FIG. 10.

Calcium deposition assay (A). The higher magnification images from micro-CT scanning showed small calcium deposition in extracellular matrices, which was indicated by circles (ACs constructs, a–c; BMCs, d–f). (B) The quantification of alizarin red staining; the values represent the ratio of absorbance of the constructs with nonseeded scaffolds and were presented as mean±standard deviation, *p<0.05. Blue color in figure 10 is the background of the image. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

These data further solidify the importance of dynamic culture conditions in enhancing bone formation processes from both ACs and BMCs. While both cell types were capable of greater calcium deposition in dynamic cell cultures, the BMCs demonstrated a greater capacity to form calcium deposits when compared with the ACs.

Discussion

MCs are capable of differentiation down the osteogenic cell pathway, making them an ideal cell source for osseous tissue engineering applications. Both ACs and BMCs have been used for bony regeneration and can be seeded onto a variety of rigid, porous scaffolds. This study is the first to use both ACs and BMCs from the same individual human donors for comparison of the cells' osteogenic potential in three kinds of bioreactors. It has been repeatedly shown that MCs are highly heterogeneous between individuals, and previous studies that compared the ability of ACs with BMCs without taking into consideration the potential confounding factors introduced by donor heterogeneity may ultimately lead to inaccurate results. Thus, reducing the effects of donor-to-donor variability allows for a more accurate evaluation of AC and BMC osteogenic potential.

DCB provides a bone niche for cells and has been widely used for bone tissue engineering studies.3 BMCs are mostly found in the cancellous bone of the human body; therefore, they are expected to grow well in scaffolds resembling cancellous bone. Interestingly, ACs instead of BMCs exhibited more efficient cellular seeding on the DCB. Histologic analysis of these constructs demonstrated a more efficient cellular seeding of ACs within the scaffold interior as compared with BMCs. The innermost aspect of cellular scaffolds has been shown to have a less negative influence on AC attachment compared with BMCs.21–23 Despite this, BMCs show greater growth than ACs under static and stirring conditions and are nearly identical under perfusion after 3 weeks in culture.

Dynamic culture, either stirring or perfusion, enhances nutritional and gas exchange from the medium to the construct. Previous work by others has shown that dynamic culture can contribute to higher cellularity and activity compared with static culture,24 but a systematic comparison has not been made between different dynamic culture environments. In our study, the stirring bioreactor, rather than the perfusion model, resulted in the highest cellularity of constructs after 21 days in culture. Bjerre et al. observed that higher cellularity was achieved in statically cultured constructs as opposed to perfusion cultured constructs when scaffolds, which contained very large pore sizes (500 μm), were used.25 In contrast, in our study, the average pore size of the scaffold is only 300 μm. In addition, we demonstrated via SEM imaging that the pores in perfusion scaffolds remained open after 21 days in culture, while cells filled the pores in scaffolds cultured in a stirred bioreactor. The stirring bioreactors likely promoted gas and nutritional exchange between the scaffold and media, with perhaps a more gentle flow to the scaffold interior as compared with the perfusion bioreactor. Conversely, the perfusion bioreactor forces a throughput flow past the interior of the scaffold, possibly limiting the ability of cells to adhere and fill the contiguous pores. Perhaps the optimal conditions for future large constructs would entail several main fluid pass-through channels to allow gentle flow driven by stirring the medium to nourish the porous interior via these main channels.

While previous studies have shown that both ACs and BMCs can express osteogenic markers and contain calcium deposits, our results demonstrated that BMCs exhibited a greater propensity for osteogenic marker expression, as shown by qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence analysis of bone markers, than donor-matched ACs.9,11,15 BMCs have been shown in fate-restricted experiments to allow for bone maintenance and regeneration and are highly stress responsive and osteolineage restricted in vivo.26 It has also been shown that BMCs can repair bone defects by augmenting marrow structure and recruiting hematopoietic cells.27 In contrast, similar results using ACs in bony defects and bone-engineered constructs are still lacking.

We further observed variance of osteogenic gene expression with different bioreactor culturing styles. Interestingly, dynamic culture enhanced RUNX-2 and OCN mRNA expression in both ACs and BMCs, which suggests that flowing medium can influence the osteogenic process of MCs. Further ALP analysis and calcium measurement indicated that stirring bioreactors are more beneficial to the osteogenesis of BMCs. It has previously been shown that MCs are mechanosensitive, in which repeated application of shear stress stimulates late phenotypic markers of osteoblastic differentiation of BMCs in a manner that depends on the duration of stimulus.11,14 Fluid flow is stronger in the perfusion bioreactor compared with the stirring bioreactor, which, in turn, causes cells that are poorly attached to the scaffold to be flushed away. Therefore, optimization of the scaffold structure and flow rates to avoid this loss of cells would be helpful for cell differentiation as well as for cellularity.

Conclusions

Donor-matched BMCs and ACs were compared in three distinct culture conditions. ACs seeded more efficiently within the interior of the DCB constructs. However, BMCs-seeded scaffolds demonstrated the greatest overall osteogenic proliferation and function in vitro. In particular, BMCs in a stirring bioreactor represented the best cell type and environment for growth of engineered bone constructs and may portend clinical success. Compared with existing, off-the-shelf, osteoconductive (possibly osteoinductive) bone substitutes, the system we describe has the benefit of a cell source, coaxed into osteogenic capabilities. The clinical uses are extremely broad—including carpal disease, long bone defects, cranial defects, Le Fort-I interpositional grafts, alveolar bone grafting, and vertebral defects. However, the limitations of this approach relate to the size and distance to the inner diameter for vascularization. So, a very large construct using this system may not be successful. The use of small-scale systems to optimize bone growth, before expanding to larger constructs, will ultimately aid in developing viable tissue-engineered bone for use in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to Benhua Sun for his assistance in Micro-CT examination and Dr. Kartoosh Heydari for his help in flow cytometry examination. This study was funded by ARRA R01 EB008388-03S1, USA. L.E.N. has a financial interest in Humacyte, Inc., a regenerative medicine company. Humacyte did not fund these studies, and Humacyte did not affect the design, interpretation, or reporting of any of the experiments herein.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kao S.T., and Scott D.D.A review of bone substitutes. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 19,513, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bose S., Roy M., and Bandyopadhyay A.Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends Biotechnol 30,546, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grayson W.L., Frohlich M., Yeager K., Bhumiratana S., Chan M.E., Cannizzaro C., et al. Engineering anatomically shaped human bone grafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107,3299, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.E L.L., Xu L.L., Wu X., Wang D.S., Lv Y., Wang J.Z., et al. The interactions between rat-adipose-derived stromal cells, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2, and beta-tricalcium phosphate play an important role in bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A 16,2927, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folgiero V., Migliano E., Tedesco M., Iacovelli S., Bon G., Torre M.L., et al. Purification and characterization of adipose-derived stem cells from patients with lipoaspirate transplant. Cell Transplant 19,1225, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y., Malladi P., Wagner D.R., Tataria M., Chiou M., Sylvester K.G., et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal cells (AMCs): a promising future for skeletal tissue engineering. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev 23,291, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monaco E., Bionaz M., Rodriguez-Zas S., Hurley W.L., and Wheeler M.B.Transcriptomics comparison between porcine adipose and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells during in vitro osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. PLoS One 7,e32481, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vishnubalaji R., Al-Nbaheen M., Kadalmani B., Aldahmash A., and Ramesh T.Comparative investigation of the differentiation capability of bone-marrow- and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by qualitative and quantitative analysis. Cell Tissue Res 347,419, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang B., Li N., Song Y., Lin Q., and Zhao R.C.Comparison of human post-embryonic, multipotent stem cells derived from various tissues. Biotechnol Lett 31,929, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu W., Niklason L., and Steinbacher D.M.The effect of age on human adipose-derived stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg 131,27, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Discher D.E., Mooney D.J., and Zandstra P.W.Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science 324,1673, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritton S.P., and Weinbaum S.Fluid and solute transport in bone: flow-induced mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 41,347, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knippenberg M., Helder M.N., Doulabi B.Z., Semeins C.M., Wuisman P.I., and Klein-Nulend J.Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells acquire bone cell-like responsiveness to fluid shear stress on osteogenic stimulation. Tissue Eng 11,1780, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreke M.R., Huckle W.R., and Goldstein A.S.Fluid flow stimulates expression of osteopontin and bone sialoprotein by bone marrow stromal cells in a temporally dependent manner. Bone 36,1047, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson E.H., Reformat D.D., Allori A., Canizares O., Janelle Wagner I., Saadeh P.B., et al. Flow perfusion maintains ex vivo bone viability: a novel model for bone biology research. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 6,769, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flores D., Liu Y., Liu W., Satlin L.M., and Rohatgi R.Flow-induced prostaglandin E2 release regulates Na and K transport in the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303,F632, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo A.B., and Jacobs C.R.Mesenchymal stem cell mechanobiology. Curr Osteoporo Rep 8,98, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yourek G., McCormick S.M., Mao J.J., and Reilly G.C.Shear stress induces osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Regen Med 5,713, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu X., Botchwey E.A., Levine E.M., Pollack S.R., and Laurencin C.T.Bioreactor-based bone tissue engineering: the influence of dynamic flow on osteoblast phenotypic expression and matrix mineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101,11203, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratcliffe A., and Niklason L.E.Bioreactors and bioprocessing for tissue engineering. Ann N Y Acad Sci 961,210, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung H.M., Won C.H., and Sung J.H.Responses of adipose-derived stem cells during hypoxia: enhanced skin-regenerative potential. Expert Opin Biol Ther 9,1499, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehman J., Traktuev D., Li J., Merfeld-Clauss S., Temm-Grove C.J., Bovenkerk J.E., et al. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation 109,1292, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stubbs S.L., Hsiao S.T., Peshavariya H.M., Lim S.Y., Dusting G.J., and Dilley R.J.Hypoxic preconditioning enhances survival of human adipose-derived stem cells and conditions endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells Dev 21,1887, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frohlich M., Grayson W.L., Marolt D., Gimble J.M., Kregar-Velikonja N., and Vunjak-Novakovic G.Bone grafts engineered from human adipose-derived stem cells in perfusion bioreactor culture. Tissue Eng Part A 16,179, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjerre L., Bunger C., Baatrup A., Kassem M., and Mygind T.Flow perfusion culture of human mesenchymal stem cells on coralline hydroxyapatite scaffolds with various pore sizes. J Biomed Mater Res A 97,251, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park D., Spencer J.A., Koh B.I., Kobayashi T., Fujisaki J., Clemens T.L., et al. Endogenous bone marrow MCs are dynamic, fate-restricted participants in bone maintenance and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 10,259, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Z., Chen F., Zhang J., He L., Cheng X., Ma Q., et al. Vitalisation of tubular coral scaffolds with cell sheets for regeneration of long bones: a preliminary study in nude mice. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47,116, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]