Significance

Human ES cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can differentiate along all the major cell lineages of the embryo proper, but there is evidence that they can also give rise to extraembryonic placental trophoblast. This observation is controversial because human ESCs (hESCs) are considered to arise from a part of the embryo that does not contribute to trophoblast. Here, we describe stable, self-renewing stem cell lines derived from hESCs and iPSCs by brief exposure to bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) that appear poised to differentiate readily along all the main developmental cell lineages, including placental trophoblast. BMP4 signaling may thus play a role in the early embryo by establishing a cell state permissive for trophoblast development.

Keywords: biological sciences, developmental biology, pluripotent stem cells, totipotent, trophoblast

Abstract

Human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) show epiblast-type pluripotency that is maintained with ACTIVIN/FGF2 signaling. Here, we report the acquisition of a unique stem cell phenotype by both human ES cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in response to transient (24–36 h) exposure to bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) plus inhibitors of ACTIVIN signaling (A83-01) and FGF2 (PD173074), followed by trypsin dissociation and recovery of colonies capable of growing on a gelatin substratum in standard medium for human PSCs at low but not high FGF2 concentrations. The self-renewing cell lines stain weakly for CDX2 and strongly for NANOG, can be propagated clonally on either Matrigel or gelatin, and are morphologically distinct from human PSC progenitors on either substratum but still meet standard in vitro criteria for pluripotency. They form well-differentiated teratomas in immune-compromised mice that secrete human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) into the host mouse and include small areas of trophoblast-like cells. The cells have a distinct transcriptome profile from the human PSCs from which they were derived (including higher expression of NANOG, LEFTY1, and LEFTY2). In nonconditioned medium lacking FGF2, the colonies spontaneously differentiated along multiple lineages, including trophoblast. They responded to PD173074 in the absence of both FGF2 and BMP4 by conversion to trophoblast, and especially syncytiotrophoblast, whereas an A83-01/PD173074 combination favored increased expression of HLA-G, a marker of extravillous trophoblast. Together, these data suggest that the cell lines exhibit totipotent potential and that BMP4 can prime human PSCs to a self-renewing alternative state permissive for trophoblast development. The results may have implications for regulation of lineage decisions in the early embryo.

Mouse ES cells, the “naive” type, are obtained from outgrowths of the inner cell mass/early epiblast of blastocysts (1) and are dependent on the growth factor leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) for maintenance of pluripotency. They may be passaged by dispersal to single cells with trypsin and can be maintained on a gelatin substratum. Human ES cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) form flattened colonies that resemble, and are considered functionally comparable to, pluripotent cells derived from the mouse epiblast, or “primed”-type stem cells (1–5). hESCs and iPSCs are maintained with activators of two signaling pathways: the BMP receptor type-1A (BMPR1A) (ALK3) pathway via ACTIVIN and the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/ERK signaling pathway via FGF2 (6–8). They do not readily survive single-cell dispersion by proteinases; rather, they must be passaged by either mechanical breakage of colonies after dispase treatment or gentle dissociation with chelating agents in presence of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitors to small clusters of cells. Moreover, they can be grown on a feeder layer or substratum coated with Matrigel (Corning), but not gelatin. Both mouse and hESCs and iPSCs are considered pluripotent and capable of differentiating to the three embryonic lineages but are generally not regarded as totipotent, because they are not considered to contribute to extraembryonic cell types (1). However, there are several reports indicating that mouse ESCs, given a suitable stimulus, can differentiate to trophoblast (9–11).

hESCs and iPSCs will also differentiate to the extraembryonic trophoblast lineage either when they are allowed to form embryoid bodies (12, 13) or when BMP4, or certain of its homologs, including BMP2, BMP5, BMP7, BMP10, and BMP13, are present in the medium and FGF2 is absent (13–24). The BMP-driven process is accelerated and directionality is enhanced if the signaling pathways that maintain the pluripotent state are inhibited (25). Trophoblast markers become up-regulated as differentiation proceeds, and an invasive HLA-G+ population and a syncytial cell population expressing CGA, CGB, ERVW1, and other signature genes gradually emerge (17, 18, 25–27). The colonies of human cells release human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), placental growth factor (PGF), placental lactogen (CSH1), and progesterone into the medium (25). All of this trophoblast differentiation can occur in either a complex medium conditioned by mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or in a chemically defined medium (25). On the other hand, if FGF2 is not removed from the culture medium before addition of BMP4, a more complex differentiation pattern materializes, with both mesoderm and endoderm, as well as extraembryonic tissues, emerging in amounts that appear to depend on the relative concentrations of BMP4, ACTIVIN, and FGF2 (5). Consequently, it might be inferred that both mouse ESCs and hESCs, when placed in an appropriate environment, can expand their developmental potential and differentiate to trophoblast.

The ability of BMP4 to initiate trophoblast differentiation from hESCs has been puzzling. In naive-type ESCs, BMP4 augments pluripotency rather than destabilizing it (28, 29), although mouse epiblast-derived ESCs in absence of ACTIVIN signaling also respond to BMP4 by expressing markers characteristic of primitive endoderm and trophoblast (2). On the other hand, embryologists have expressed doubt as to whether “epiblast”-type stem cells could give rise to trophoblast, a lineage that segregates from the inner cell mass before the epiblast has formed (30, 31).

Here, we present evidence that BMP4 acts to enhance the potency of hESCs and iPSCs, making them readily capable of forming both embryonic and trophoblast lineages. Previously, we reported that only a transient, 24-h exposure to BMP4 was necessary for hESC colonies to commit to trophoblast. Thereafter, the ACTIVIN signaling inhibitor A83-01 and FGF2 signaling inhibitor PD173074, in the complete absence of BMP4, were sufficient to promote a full display of markers for differentiated trophoblast sublineages (25). The goal of the current study was to maintain stable cell lines in the state reached just after brief exposure to BMP4, A83-01, and PD173074 (BAP). We had initially predicted that these cells would be present early in the trophoblast lineage, possibly even in trophoblast stem cells. Instead, these lines represent a unique type of human pluripotent stem cell (PSC).

Results

Isolation of BAP-Converted ESC and iPSC Lines.

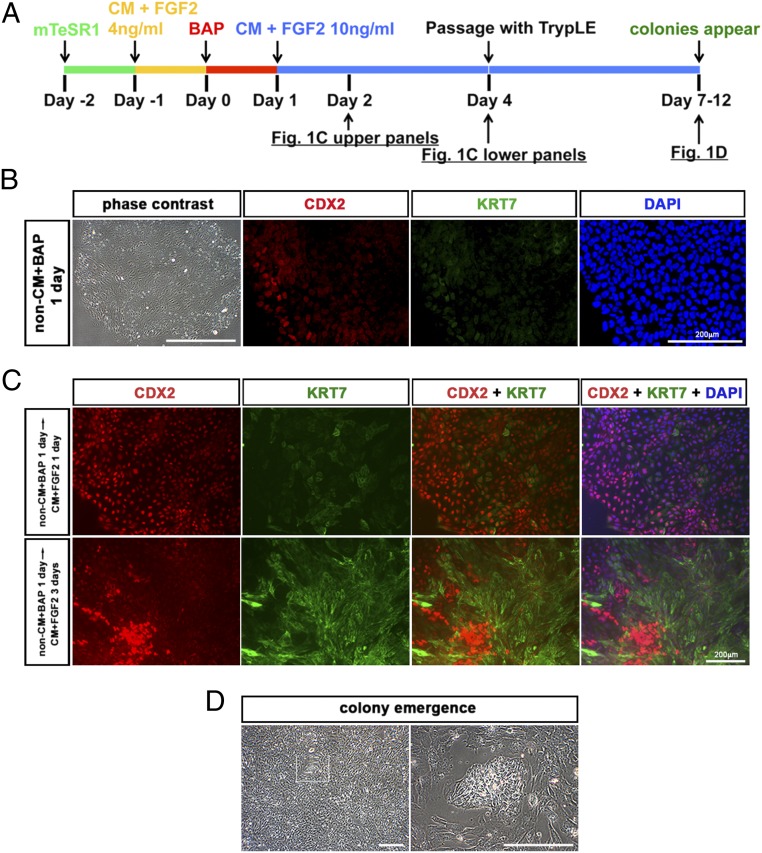

H1 (WA01) cells, H9 (WA09) cells, and iPSC cells were routinely cultured on a Matrigel substratum on mTeSR1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies) (32). To initiate differentiation toward trophoblast, colonies were subcultured; on the following day, the culture medium was changed from the defined mTeSR1 medium to the MEF-conditioned DMEM/F12/KOSR medium (MEF-CM), which contains lower concentrations of recombinant FGF2 (4 ng/mL) than mTeSR1 medium and no supplementary TGF-β (Fig. 1A). After a further 24 h, the medium was changed again to one lacking FGF2 but containing BMP4 (10 ng/mL), the ALK4/5/7 inhibitor A83-01 (1 μM), and the FGF2-signaling inhibitor PD173074 (0.1 μM) (BAP treatment) in nonconditioned DMEM/F12/KOSR medium (hESCM). Control cultures continued to be grown in the same basal medium in the presence of FGF2 and in the absence of BMP4 and inhibitors. At this stage, the BAP cultures remained negative for KRT7, but many cells, particularly on the periphery of the colonies, stained weakly for CDX2 (Fig. 1B), although they converted completely to a KRT7+/CDX2+ state if kept in this medium for a further day (25).

Fig. 1.

Procedure for deriving PSCBP colonies. (A) Human ESC lines (H1 and H9) and a well-characterized human iPSC line were progressively cultured on mTeSR1 medium (green line) and conditioned medium containing FGF2 (4 ng/mL) (CM + FGF2) for 24 h (yellow line), and then treated with BAP (BMP4, 10 ng/mL; A83-01, 1 μM; PD173074, 0.1 μM; red line) for 24 h (25). To prevent further progression along the trophoblast lineage, the medium was changed to standard ESCM lacking BAP (blue line) and containing FGF2 (10 ng/mL). After a further 3 d (day 4), the colonies were dispersed to single cells with TrypLE and cultured on the same FGF2-containing medium on a gelatin substratum. (B) Images of H1 colonies treated with BAP for 24 h (red-line phase). Cells had an epithelium-like morphology in a phase-contrast image, and some, near the periphery of colonies, were CDX2+. KRT7 immunofluorescence was very faint. Nuclear stain with DAPI was captured at the same site. (C) Images of H1 colonies in standard ESCM with FGF2 after the transient BAP treatment (blue-line phase). (Upper) H1 colonies 24 h after removal of BAP (day 2) when most cells were CDX2+. Variable KRT7-expressing cells within the colonies were also detectable. (Lower) H1 colonies 3 d after removal of BAP (day 4). Cells in the colony were consistent with cells seemingly organized into patches of strongly CDX2+ but KRT7− cells and cells with down-regulated CDX2 and highly up-regulated KRT7. (D) Colonies emerged among a background of scattered surrounding cells between days 3 and 8 after passage with TrypLE (days 7–12). (Scale bars: phase-contrast images, 500 μm; immunofluorescence images, 200 μm.)

After the initial 24-h exposure to BAP conditions, the culture medium was changed to MEF-CM containing FGF2 (4 ng/mL) (Fig. 1A). After 24 h on this medium, all cells stained positively for CDX2 but KRT7 staining was weak and less uniform, with many areas of the colonies remaining negative for this antigen (Fig. 1C, Upper). After 3 d, defined patches of CDX2+/KRT7− cells were evident and appeared to be organizing into colonies (Fig. 1C, Lower). These regions of clustered cells that stained for CDX2 were encompassed by KRT7+ cells. At day 4, soon after these disorganized colonies became evident, the cultures were dispersed into single cells with TrypLE and passaged at a 1:2 ratio onto 0.1% gelatin-coated culture wells in the same MEF-CM with 10 ng/mL FGF2.

In most experiments, well-formed colonies began to emerge within 3–8 d (Fig. 1D), and where colonies had not emerged so early, they did so after the next passage. Thereafter, cells from colonies can be passaged approximately every 3 d at a ratio of 1:3 or 1:4. To distinguish these new cell lines from their progenitor PSC lines, each is provided with the same cell line designation followed by the subscript BP (BAP-primed). Hence, the derivative cell lines from H1 cells are named H1BP cells. That these H1BP colonies are distinct from the precursor H1 cells is evident from their comparative morphologies. For example, the H1BP cells appeared to be flatter and to have a larger surface area, reflecting a greater cytoplasm-to-nuclear ratio, than the parental H1 cells (Fig. 3 A and E). They also displayed more distinct cell margins (Fig. S1A). These morphological differences were also observed during culture on Matrigel (Fig. 3E), and so were not a consequence of a particular substratum. However, when H1 and H1BP cells were evaluated for relative size after dispersion to single cells, their diameters did not differ [6.33 ± 0.17 μm for H1 cells vs. 6.17 ± 0.17 μm for H1BP cells (n = 3, with each experiment performed on >5 × 105 cells)], suggesting that the differences evident during culture were a reflection of their respective interactions with the substratum. When H1BP colonies were dispersed to single cells by TrypLE and plated on a gelatin substratum, 73 ± 5% (n = 3) cells attached to the substratum within 24 h and formed well-developed colonies within 3 d (Table S1). By contrast, parental H1 cells did not survive complete dispersion to single cells by TrypLE and could not be propagated on a gelatin substratum (Fig. S2 and Table S1). H1 cells passaged in the standard manner as small clumps (∼100 μm in diameter) by dispase treatment, followed by mechanical dissociation with a cutting tool, also failed to grow on gelatin (Fig. S2C).

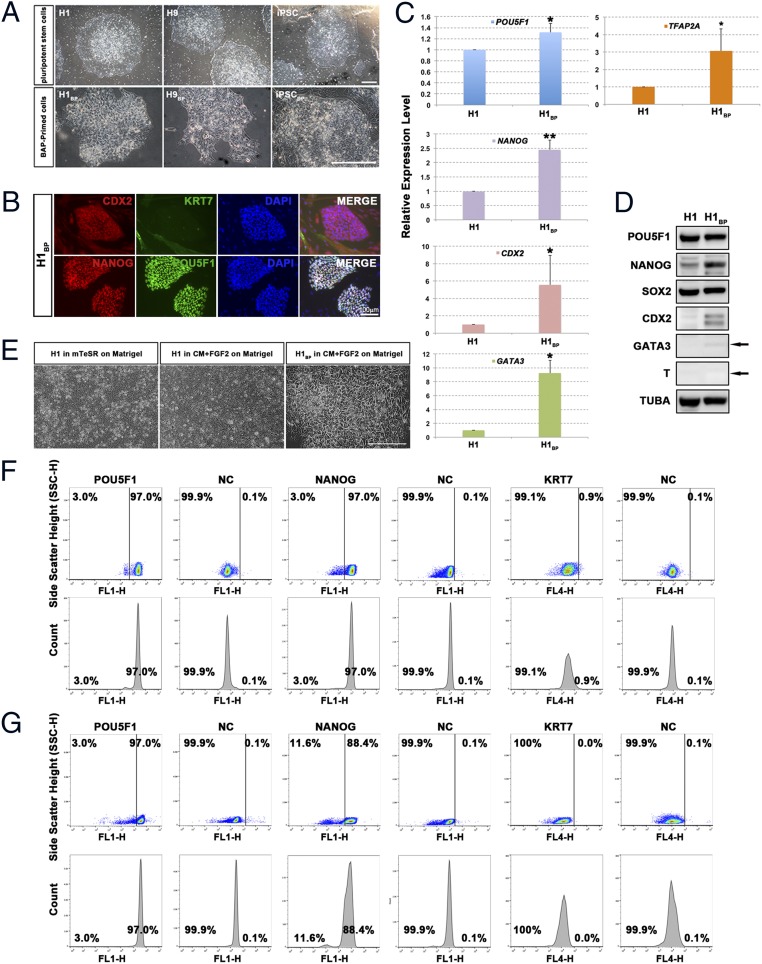

Fig. 3.

Characterization of PSCBP colonies. (A) Typical colony morphologies of H1 cells, H9 cells, and iPSCs (Upper) and of H1BP cells, H9BP cells, and iPSCBP (Lower). (Scale bar: 500 μm.) (B) H1BP colonies immunostained for CDX2, KRT7, NANOG, and POU5F1. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C) Real-time PCR assessments (n = 3; i.e., three RNA preparations from three independent experiments) of relative concentrations of transcripts for POU5F1, NANOG, CDX2, GATA3, and TFAP2A in H1BP cells relative to H1 cells (with GAPDH as an endogenous standard). To provide comparisons, the mean concentration of each transcript in H1 cells has been assigned a value of 1 (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; mean ± SD). (D) Western blotting of SDS gels used for analysis of proteins present in 30 μg of H1 and H1BP cell extracts. The arrow indicates the anticipated mobility of GATA3 and T (Brachyury) based on their migration rate (Mr). All analyses were performed on the same 10% polyacrylamide gel. TUBA, α-tubulin. (E) Morphology of H1 cells cultured on Matrigel in mTeSR1 medium or CM supplemented with 10 ng/mL FGF2 and H1BP cells cultured on Matrigel in CM supplemented with 10 ng/mL FGF2. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) Flow cytometry histograms for POU5F1, NANOG, and KRT7 expression in H1BP (F) and H1 (G) cells are shown. For the negative control (NC), cells were exposed to IgG and a second antibody without prior exposure to primary antibodies.

The protocol described above works successfully for H1 cells, H9 cells, and iPSCs (Fig. 2), and it has been performed repeatedly with H1 cells (Fig. 2). For each of the cell lines, colony self-renewal can be extended over multiple passages with no measurable change in population doubling times. However, extended passage (>25 passages) of H1BP and H9BP lines has led to variable degrees of chromosomal instability (Fig. S3). For example H1BP cells have been noted with trisomy 12 and other signs of chromosomal instability in late-passage cells when trypsin had been used for regular cell passage. H9BP cells also show karyotype abnormalities (e.g., translocations involving chromosomes 8 and 18) as passage numbers are extended (Fig. S3). Such aberrations associated with trypsin passage have been commonly noted in hESCs (33). A more gentle dispersion to single cells with nonenzymatic reagents, rather than the continued use of trypsin, has so far provided chromosomal stability over 16 passages (Fig. S3).

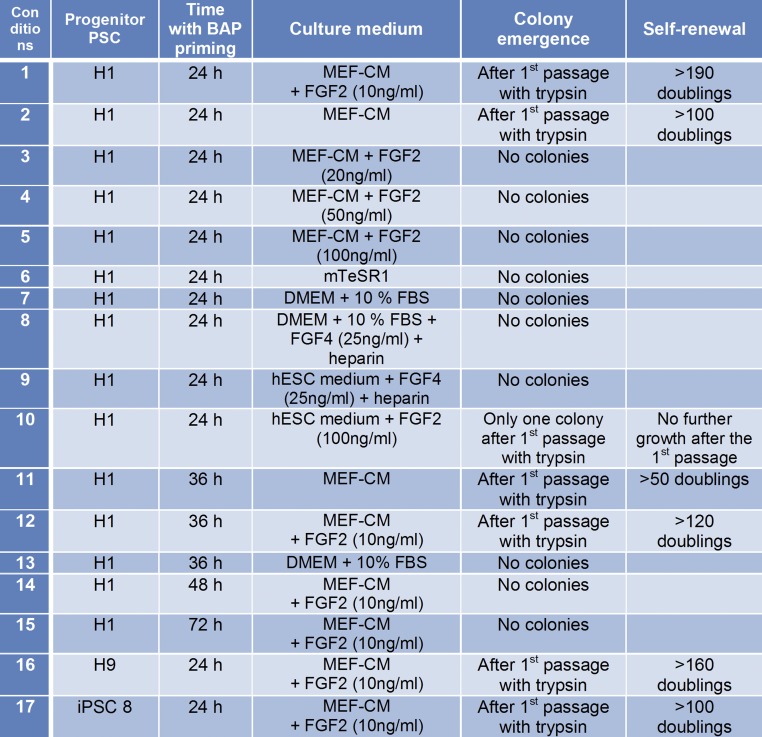

Fig. 2.

Summary of conditions used to derive and maintain of PSCBP. Trypsin is TrypLE (recombinant trypsin).

Colonies can also be derived if the initiating BAP conditions are extended to 36 h, but not to 48 h or beyond (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1B). The emergence of colonies is also sensitive to the concentration of FGF2 in the culture medium. No lines have been successfully derived when FGF2 exceeded 10 ng/mL (Fig. 2, conditions 3–5 and 10). Similarly, the H1BP cells could neither be generated nor maintained in mTeSR1 medium, which contains high concentrations of FGF2 (100 ng/mL) (Fig. 2 condition 6). H1BP colonies can be generated, and subsequently maintained, on conditioned medium without supplemental FGF2 (Fig. 2, conditions 2 and 11); however, as shown later (Fig. S1C), such colonies stain less intensely for NANOG and POU5F1 than the ones grown with added FGF2. These results are consistent with the conclusion that the H1BP cells require only low concentrations of FGF2, which can be supplied minimally in the MEF-CM (34). Importantly, self-renewing H1BP colonies could not be generated in nonconditioned ESC medium, even in presence of FGF2 (Fig. 2, condition 10), suggesting that in addition to FGF2, some other factor released by MEFs and present in conditioned medium is required for growth.

Finally, no colonies could be generated under conditions used to derive and maintain trophoblast stem cells from mouse conceptuses (35, 36) (Fig. 2, conditions 8 and 9). Colonies did form when FGF4 was used in association with MEF-CM, but there was no indication that this colony formation occurred more efficiently than when the FGF4 was omitted.

Phenotype of the BAP-Primed ESC and iPSC Lines.

The PSCBP colonies were distinct in several features from the initiating H1 cells, H9 cells, and iPSCs (Fig. 3A and Table S1). They were weakly positive for CDX2, negative for KRT7, but strongly positive for POU5F1 and NANOG (Fig. 3B and Fig. S1 D and E). By contrast, the scattered surrounding cells still present in the cultures at early passage did not form colonies and were negative for POU5F1 and NANOG, but positive for KRT7, indicating they had probably converted to trophoblast. Two approaches were used to minimize the contribution of these trophoblast cells as culture continued. The first approach was to dissociate the colonies to single cells, such that no clumps were present, and then to allow the cell suspension to settle. Under these conditions, the larger KRT7+ cells sank more quickly, causing the upper layer to become enriched with cells from the colonies. When the latter were replated, the background of epithelial cells was markedly reduced (Fig. S1F). The second approach, shown here for H1BP cells but also successful with other lines, was to passage the cells repeatedly at a lower split ratio (1:6–1:8). Over extended passage, the cultures progressively lost the KRT7+ components and became composed solely of colonies similar to those colonies shown in Fig. S1F. Thus, the KRT7+ supplemental cells were not required to maintain H1BP self-renewal.

The increased expression of POU5F1 and NANOG transcripts, inferred from immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3B and Table S2), was confirmed by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 3C and Table S3). Expression of POU5F1 and NANOG was higher in H1BP cells than in H1 cells. CDX2, GATA3, and TFAP2A transcripts were also significantly up-regulated, but levels of all three were low, requiring more than 28 amplification cycles when the internal control, GAPDH, was detected after only about 17 cycles.

Flow cytometry demonstrated that dissociated colonies of both H1BP cells (passaged by single-cell dissociation) and H1 cells (passaged by mechanical dispersion but dissociated by TrypLE before fixing and staining for flow cytometry) were highly uniform in terms of expression of POU5F1 and were >99% negative for KRT7 staining (Fig. 3 F and G and Table S4). H1BP colonies also provided a highly homogeneous population of cells positive for NANOG, whereas H1 cells were more heterogeneous for NANOG staining and included some cells that stained only weakly, if at all, for this transcription factor. These experiments have been repeated on at least three different occasions with similar outcomes. In the case of H1BP cells, the flow cytometry was performed with different clonal populations of cells. Each was highly homogeneous in terms of POU5F1 and NANOG staining.

Western blot analysis performed on colony lysates verified that H1BP cells expressed POU5F1, NANOG, SOX2, CDX2, and GATA3 (Fig. 3D and Table S5). The up-regulation of NANOG, CDX2, and GATA3 in H1BP cells relative to H1 cells was clearly evident in these Western blotting experiments. However, these data were not as clear-cut for H9BP cells and iPSCBP. With the H9BP cells, there appeared to be increased expression of POU5F1, NANOG, and SOX2 relative to the parental H9 cells (Fig. S1D, Left), but expression of CDX2 and GATA3 was much lower than noted in the H1BP cell line. In iPSCBP/iPSC comparisons, expression of POU5F1, NANOG, and SOX2 was similar, whereas CDX2 expression was increased in iPSCBP (Fig. S1D, Right). Despite these differences, both of these cell lines successfully survived complete proteolytic dispersion to single cells, could be maintained on a gelatin substratum (Fig. 2, conditions 16 and 17), and displayed no sign of differentiation.

Microarray Analysis.

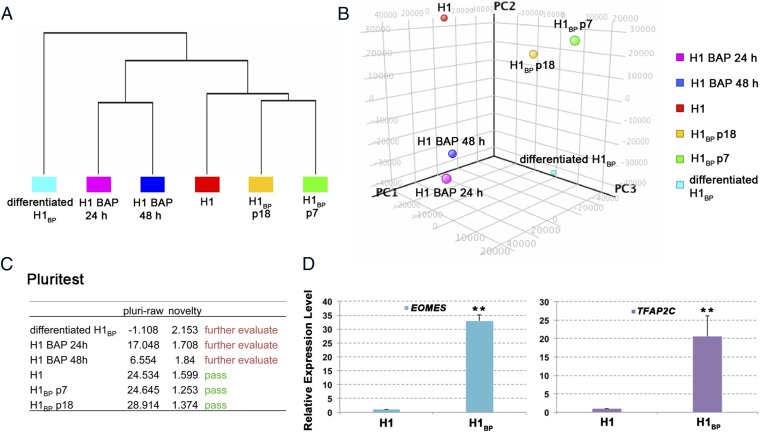

RNA was isolated from control H1 cells, from H1 cells exposed to BAP conditions for 24 and 48 h, from H1BP colonies picked individually at two different passage numbers (p7 and p18), and from H1BP cells that had been allowed to differentiate spontaneously in the absence of FGF2 (Fig. 4A). The latter cells are discussed in greater detail in the next section. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis of the data (Fig. 4 A and B) showed that the H1BP cells had distinct transcriptional profiles from the progenitor H1 cells and H1 cells treated with BAP for 24 h. H1BP cells at different passage numbers had also diverged somewhat in terms of their gene expression profiles.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the transcriptomes of H1 colonies and H1BP colonies at two different passage numbers (p7 and p18) in H1 colonies that were exposed to BAP conditions for 24 and 48 h and H1BP colonies that had been allowed to differentiate spontaneously [10 d on defined hESCM medium (i.e., nonconditioned ESC medium minus FGF2 and BMP4, differentiated H1BP cells). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering (A) and principal component analysis of microarray data (B), outcomes of analysis by the PluriTest (www.pluritest.org) based on overall gene expression (C), and confirmation of the >twofold up-regulation of two genes (EOMES and TFAP2C) in H1BP vs. H1 cells by real-time PCR (D). Conditions were as in Fig. 3C (**P < 0.01). PC, principal component.

Analysis by the pluripotency test (PluriTest) (Fig. 4C), a bioinformatics tool that provides an assessment of whether or not human cells are pluripotent by their expression of a relatively large number of gene markers consistently associated with hESCs and iPSCs (37), indicated that the H1BP cells had transcriptional profiles consistent with pluripotency and pluri-raw scores comparable to the pluripotency and pluri-raw scores of H1 cells. The novelty scores, which essentially measure deviation from the expected gene expression pattern of an idealized human pluripotent cell line, were also low. By contrast, the cultures of H1 cells that had been treated with BAP for 24 h and from which the H1BP cells ultimately emerged had already diverged from their parental H1 cells and lost pluripotency. This drift from pluripotency was further accentuated after 48 h of BAP treatment.

A total of 110 genes were up-regulated greater than twofold in the two H1BP cell samples relative to H1 cells (Fig. S4 and Dataset S1). Among the most strongly up-regulated genes were NODAL, CER1 (which encodes cerberus, a BMP antagonist), F2RL1, LEFTY1, LEFTY2, GDF3, GAL, and SCGB3A2 (which encodes secretoglobin, a surfactant protein). In addition to these genes, there was significant up-regulation of at least two other potential trophoblast stem cell markers, namely, EOMES and TFAP2C, whose increased expression in the H1BP colonies was confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 4D).

Teratoma Formation.

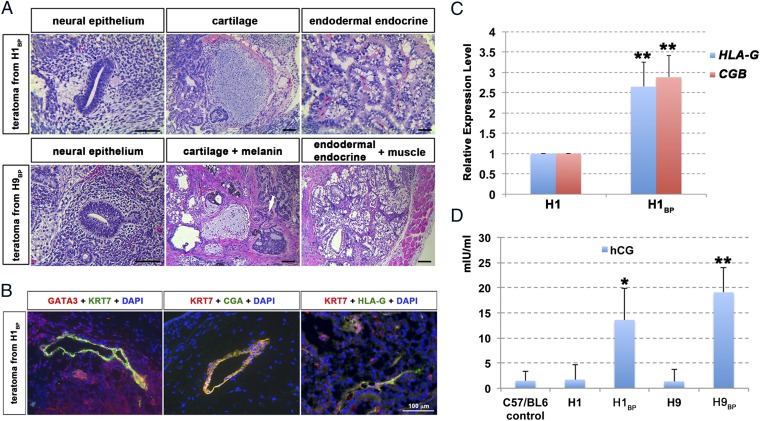

H1 cells, H1BP cells, H9 cells, H9BP cells, iPSCs, and iPSCBP all gave rise to teratomas in immunodeficient mice. In each case, the tumors included tissue representative of ectoderm (neural epithelium and melanin-producing cells), endoderm (gut-like epithelium accompanied by secretory glands), and mesoderm (muscle and cartilage tissues, shown for H1BP and H9BP cells in Fig. 5A). Immunostaining of sections for KRT7, which is a broadly used marker for trophoblast, and for the transcription factor GATA3 revealed a few small regions of positive tissue adjacent to open, vacuole-like structures resembling lacunae of the early human placenta (Fig. 5B). Such regions were also positive for CGA, and hence are potential trophoblast, but cellular detail was insufficient to determine whether syncytial structures were present (Fig. 5B). A few regions within the tumors showed positive HLA-G and KRT7 staining (Fig. 5B). The presence of HLA-G and CGB transcripts in the teratomas was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 5C). In addition to these potential indicators of trophoblast, mice carrying tumors derived from H1BP or H9BP cells, but not mice with H1 cell, H9 cell, or iPSCBP tumors, had serum concentrations of hCG significantly higher than control mice and mice harboring H1 and H9 teratomas (Fig. 5D). Together, these data indicated that all of the cell lines were pluripotent and that the H1BP and H9BP teratomas contained small amounts of tissue that was possibly trophoblast.

Fig. 5.

In vivo differentiation of PSCBP. (A) Histological analysis of teratomas generated from H1BP (Upper) and H9BP (Lower) cells after injecting 107 cells into the dorsal flanks of nonobese diabetic SCID-γ mice for 6.0 and 6.9 wk, respectively. The tissue sections were stained by H&E and indicate the presence of representative ectoderm-derived [Left, neural epithelium; Lower Center, melanin-producing cells (white arrow)], endoderm-derived (Right, gut-like epithelium accompanied with secretory glands), and mesoderm-derived (Center, cartilage tissues; Lower Right, muscle) tissues. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (B) Immunohistological images show areas of presumptive trophoblast staining for GATA3+ and KRT7+, CGA+ and KRT7+, and HLA-G+ and KRT7+ cells from H1BP teratomas. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C) Real-time PCR assessments (n = 3; i.e., three PCR reactions from the same RNA preparation from each teratoma) of relative concentrations of transcripts for HLA-G and CGB in an H1BP teratoma relative to an H1 teratoma (with GAPDH as an endogenous standard). To provide comparisons, the mean concentration of each transcript in H1 cells has been assigned a value of 1 (**P < 0.01; mean ± SD). (D) Comparisons of hCG concentrations (mIU/mL) in sera of control mice (first column) and mice bearing teratomas from H1, H1BP, H9, and H9BP cells (second–fifth columns). Values (mean ± SD) for mice carrying teratomas from H1BP and H9BP cells are significantly higher than in controls (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01), where hCG concentrations for control mice and mice with H1 and H9 teratomas were close to the detection limit of the ELISA.

In Vitro Differentiation.

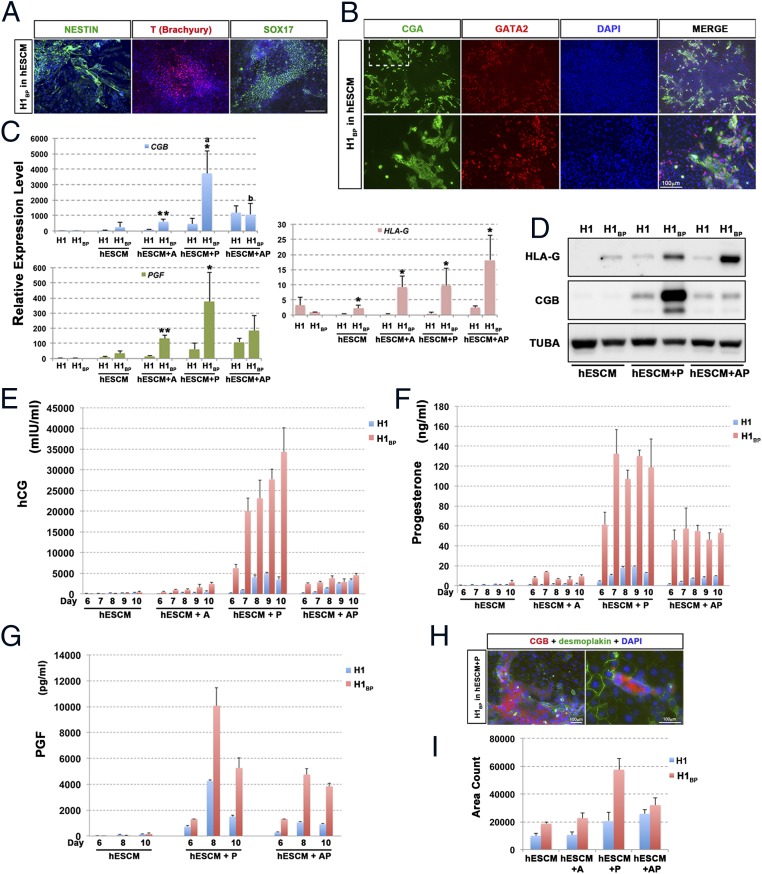

Although the PSCBP lines could self-renew, removal of FGF2 and replacement of the MEF-CM with nonconditioned ESC medium lacking FGF2 (hESCM) led to initiation of differentiation within the colonies (Fig. 6A and Fig. S5A). Within 10 d of culture in hESCM, many colonies possessed regions of cells that were positive for NESTIN, T (BRACHYURY), and SOX17 (Fig. 6A). The colonies also release α-fetoprotein into the medium, consistent with a partial endodermal phenotype (Fig. S5B). Additionally, there were regions that were positive for CGA and GATA2 (Fig. 6B), and hence likely to be trophoblast. There was also considerable heterogeneity in colony morphologies and in the distribution of markers among the colonies within a particular culture well. The differentiated colonies produced hCG, progesterone, and PGF, although in relatively small amounts relative to when differentiation was driven by PD173074 (0.1 μM), A83-01 (1 μM), or both inhibitors together (Fig. 6E and Table S6). Thus, all three main germ layers, as well as trophoblast, appeared to be represented among these differentiating colonies. The expression of additional markers for trophoblast (transcripts for CGB, PGF, and HLA-G) and their increased expression in differentiated H1BP cells relative to undifferentiated cells (maintained on MEF-CM plus 10 ng/mL FGF2) was confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

In vitro differentiation of H1BP cells. (A) Differentiation of H1BP cells to colonies containing presumptive ectoderm (NESTIN), mesoderm (T, Brachyury), and endoderm (SOX17) by culturing in basal, chemically-defined hESCM without any growth factors for 10 d. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (B) Some colonies cultured as in A also contained areas of presumptive trophoblast, which were positive for both CGA (green) and GATA2 (red). (C) Comparison of relative expressions of CGB, PGF, and HLA-G in H1 and H1BP colonies that had been cultured under five different culture conditions [1, controls in MEF feeder cell-conditioned medium plus FGF2; 2, hESCM with no additions (hESCM); 3, hESCM plus A83-01 (hESCM + A); 4, hESCM plus PD173074 (hESCM + P); 5, hESCM plus A83-01 and PD173074 (hESCM + AP)] for 10 d. The values are the mean ± SD for three separate experiments. Comparisons between H1 and H1BP cells under each culture condition were evaluated by the Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). Values across treatments were assessed by ANOVA (different letters indicate values differed from each other by at least P < 0.05). (D) Representative Western blot comparing relative concentrations of HLA-G and CGB in H1 and H1BP cells cultured in either hESCM with no additions or in the same medium supplemented with A, P, or A plus P. The data were all from the same blot of a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide blot (30 μg of protein per lane). The loading control is TUBA. Comparison between H1 (blue bars) and H1BP (red bars) cells in production of three placental hormones [hCG (E), progesterone (F), and PGF (G)] over time of culture in four different media (hESCM, hESCM + A, hESCM + P, and hESCM + AP as defined above) for up to 10 d. The values are the mean ± SD for three separate experiments. The medium was replaced daily, such that values represent daily production and release of the hormones to the medium. Analyses of PGF were limited to days 6, 8, and 10 and to just three of the media for cost considerations. The values for hCG production are also illustrated in Table S6 to demonstrate that measurable amounts of hormone were secreted in the hESCM by both cell types. (H) In the presence of PD173074 (hESCM + P), large areas of syncytiotrophoblasts were detected by double staining for DSP (green) and CGB (red), indicating that the syncytial areas had a continuous cytoplasm and contained multiple nuclei. (I) Quantification of syncytial areas (immunostaining for CGB+) from H1 and H1BP cells in four different media (hESCM, hESCM + A, hESCM + P, and hESCM + AP as defined above) for 10 d. CGB+ areas from nine frames of each experiment were automatically counted by imageJ software (NIH) and averaged.

Differentiation to trophoblast was increased in the presence of PD173074 or A83-01 and PD173074 (Fig. 6 C–F), as reflected in the release of hCG and progesterone by the cultured cells assessed at 24-h intervals from day 6, when the production of these hormones was initiated, until day 10 of treatment. Under all three inhibitor treatment conditions, the H1BP cells produced significantly greater amounts of the two hormones than when the inhibitors were omitted, although both hCG and progesterone were measurable in the hESCM controls, albeit in small amounts (Fig. 6E and Table S6). However, although A83-01 promoted only a modest increase relative to controls, PD173074 had a major effect. These effects of PD173074 were much greater on the H1BP cells than on the H1 cells. Not only were daily amounts of hCG and progesterone enhanced by PD173074 but the onset of detectable production was always earlier than in the controls. Quantification of a CGB+ syncytial area on day 10 of treatment was consistent with the ELISA results (Fig. 6I). Double-staining the colonies for desmoplakin (DSP), a component of functional desmosomes and CGB, indicated that the hCG production was largely limited to cellular regions where the cytoplasm appeared continuous and contained several nuclei (Fig. 6H), whereas the cells that were negative for CGB contained a single nucleus and were enclosed by a DSP-staining outer surface.

The combination of PD173074 and A83-01 led to a lower production of hCG and progesterone than with PD173074 alone, although amounts under both treatments remained higher than with A83-01 alone. That the H1BP cells were responding differently to PD173074 than to PD173074 and A83-01 in combination is also illustrated in Fig. 6D. Here, it is clear that CGB and HLA-G expression had been boosted by PD173074, whereas the combination of both drugs led to a much augmented production of HLA-G relative to CGB. These data for CGB are consistent with the qPCR outcomes (Fig. 6C), where PD173074 alone increased CGB transcript levels ∼10-fold in H1BP cells relative to H1 cells exposed to the same conditions. qPCR data for HLA-G were more complex but confirmed the enhanced expression in response to PD173074 and A83-01 in combination than with PD173074 alone. Experiments to follow PGF expression (Fig. 6G) confirmed that the control cultures maintained in hESCM produced low amounts (∼100 pg/mL) of hormone and that production was enhanced ∼100-fold with PD173074 and, to a lesser extent, in response to PD173074 and A83-01 together. Comparable results have been obtained with the other cell lines. Fig. S5D, for example, indicates that H9BP cells also have contrasting responses to PD173074 and to PD173074 and A83-01 together in terms of hCG production. H9 cells, although responding to PD173074 with a later onset of hCG production than H9BP cells, did produce large quantities of the hormone, particularly by day 10 of culture (compare Fig. 6E with Fig. S5D). Differences with regard to responses to inhibitors between H1 and H9 ESCs have been noted previously (25).

Discussion

Our original goal was to isolate trophoblast stem cells from hESCs by brief exposure to BAP. Together, this regimen of factors efficiently drives hESCs to a uniformly KRT7+ state in 48 h (25). The hypothesis was that after about 24 h of treatment, and around the time they became CDX2+, the cells would be passing through a transient trophoblast stem cell stage before differentiating into more advanced trophoblast lineages. Confidence that this hypothesis was correct was raised when it proved possible to derive colonies from H1 and H9 cells exposed to this differentiation protocol under culture conditions that would not support the growth and passage of the initiating ESCs themselves (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2). The cells comprising these colonies also possessed a number of features that initially led us to believe that they might indeed be trophoblast stem cells. For example, under appropriate culture conditions, they were self-renewing and weakly positive for CDX2, and could be readily converted to differentiated cell populations that expressed a suite of trophoblast markers (Fig. 6). However, it soon became obvious that rather than being trophoblasts, the cells were quite closely related to, but nevertheless distinct from, their pluripotent progenitors (Fig. 3). In the discussion that follows, we first consider the identities of these cells. Second, we ask whether or not these cells are totipotent. Third, we propose that ESCBP and iPSCBP can potentially provide improved models for following syncytiotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast differentiation by varying the concentration of PD173074 and A83-01 in the culture medium. Finally, we readdress the ongoing controversy relating to how hESCs and iPSCs might harbor trophoblast potential and discuss the role played by BMP4 in this process.

Are ESCBP/iPSCBP (PSCBP) Distinct from Their Pluripotent Progenitors?

There seems little doubt that H1BP cells and their H9 and iPSC homologs are pluripotent as gauged by the usual criterion of being able to differentiate along the three main germ cell lineages (Figs. 5 and 6). The undifferentiated BP cells also express the usual transcription factors associated with the pluripotent state and “passed” the PluriTest (37) (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, the BP cell lines differ in several key respects (Table S1) from the cells from which they were derived. In particular, they are morphologically distinct from the initiating ESCs whether they are cultured on Matrigel or gelatin (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1). They can be propagated clonally on gelatin from single cells after trypsin treatment and have transcriptome profiles that distinguish them from their ESC/iPSC progenitors (Fig. 4 and Fig. S4). The relevance of elevated, somewhat varied expression of several genes encoding transcription factors that may direct trophoblast formation (38–40) (e.g., GATA3, TFAP2A, TFAP2C, CDX2, EOMES) is unclear but might reflect the fact that such cells are hovering on the point of differentiating along that lineage (i.e., transcriptionally primed) as soon as the pluripotent gene networks are down-regulated. Although the observation that CDX2 was coexpressed with POU5F1 in the undifferentiated H1BP cells might be considered surprising, CDX2 expression has been consistently observed in rat ESCs (41–43) and associated with POU5F1 expression in human (44) and bovine (45) embryonic trophectoderm. More unexpected was the coexpression of CDX2 with NANOG, because the two transcription factors have mutually antagonistic effects in mouse ESCs and preimplantation embryos (46).

One possible origin of the PSCBP is that they were selected from a small residual population able to survive in a pluripotent state despite exposure (24 h or 36 h) to BAP conditions. Conceivably, such cells existed in a “sporadic superstate” (47) and were already present as a minority population of NANOG-overexpressing cells within the parental ESC and iPSC colonies. Heterogeneity exists in ESC colonies (48–50) and is evident for NANOG staining of H1 cells (Fig. 3G). Such heterogeneity is not apparent for H1BP cells, which are highly homogeneous for NANOG and POU5F1 expression. Moreover, lines resembling H1BP and H9BP cell lines cannot be derived directly from parental H1 and H9 cell colonies by simply dispersing the latter to single cells and capturing survivors on a gelatin substratum (Fig. S2). Furthermore, our stock populations of ESCs and iPSCs are routinely maintained on mTeSR1 medium, which does not support H1BP cell self-renewal and would presumably have purged such cells from the population. Accordingly, we believe that such cells arise transiently in response to brief BAP treatment.

Are PSCBP Totipotent?

ESCs and iPSCs are considered pluripotent in that they differentiate to all three embryonic germ layers but are not generally believed to be capable of giving rise to extraembryonic tissue, including trophoblast (1). Although the H1BP cell lines differentiated spontaneously along the three main germ cell lineages in what appears to be a stochastic manner when FGF2 and MEF-CM were withdrawn and replaced with a defined medium that lacked any growth factors, they also readily formed trophoblast (Fig. 6B). Additionally, H1BP and H9BP cells differentiated predominantly, if not completely, to trophoblast when PD173074 alone or in combination with A83-01 was added to the defined ESCM (Fig. 6 C–E). Interestingly, cell lines with the capacity to contribute to extraembryonic as well as embryonic tissues have been described recently for the mouse (49, 51). We suggest that both the aforesaid mouse lines and the PSCBP lines described here have achieved a state that is permissive to form trophoblast in addition to differentiated derivatives of the three main germ layers. A number of genes associated with pluripotency are up-regulated in PSCBP, especially LEFTY1, LEFTY2, and NANOG, and could prove to be useful markers of this BMP-primed state.

Consistent with this idea were the observations on the H1BP and H9BP teratomas, which were composed largely of an array of fetal tissue types (Fig. 5A) but also included small regions that were trophoblast-like in that they were positive for KRT7 and GATA3 and for KRT7 and CGA, as well as being located adjacent to vacuolar-like spaces that might be analogous to the lacunae present in the immature human placenta (52) (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the mice carrying tumors from the H1BP and H9BP cells had significantly elevated concentrations of hCG in their blood (Fig. 5D). Care must be taken in evaluating the teratoma data, however. Many human tumors express CGB (53–55), and some secrete placental CG and CSH1 (56), whereas others, including aggressive breast carcinomas, contain areas that are both GATA3+ and KRT7+ (57). Because the areas of teratomas expressing trophoblast markers were sporadic and not well characterized histologically, the proof that they represent fetal placenta remains weak. In addition, it is clear from the relative amounts of different tissues within the tumors that introduction of the stem cell under the skin of the mice favored differentiation along the three main germ-line images and not to trophoblast.

PSCBP as an Improved Model for Trophoblast Differentiation.

The outcomes with different inhibitor combinations on the ESCBP were not identical. With the FGF2-signaling inhibitor (PD173074) alone, markers of syncytiotrophoblast predominated, which represents an outcome quite similar to the outcome observed by Sudheer et al. (20), who noted that another FGF inhibitor, namely SU5402, in the presence of 10 ng/mL BMP4 drove H1 and H9 cells largely to syncytiotrophoblast. Intriguingly, in our experiments, the presence of the second inhibitor, A83-01, which targets the ALK4, ALK-5, and ALK-7 receptors, and hence ACTIVIN/NODAL/TGF-β signaling, led to a smaller area of CGB+ cells within colonies than PD173074 (Fig. 6I), reduced the amount of placental hormones released into the medium, and accentuated expression of HLA-G, suggesting that the colonies contained a higher proportion of extravillous trophoblast. Confirming these hypotheses will require additional experiments, but the ability to bias trophoblast differentiation toward either cell type might be of value in understanding the pathobiology of a disease like pre-eclampsia, where placental development appears to be abnormal (58).

Role for BMP4 in the Generation of Trophoblast from epi-ESCs.

We propose that short-term exposure to BMP4 in presence of the two inhibitors causes the PSC to undergo a transition to a “BMP-primed” state, such that the cells remain self-renewing and continue to display a pluripotent signature but are poised to differentiate to trophoblast much more efficiently than if they had not been BMP4-exposed. A somewhat similar role has been envisioned for BMP4 in conserving a stable “ground state” for naive-type stem cells from the mouse (28, 29), where in association with the growth factor LIF, BMP4 helps preserve the potential of the ESCs for multilineage differentiation, chimera formation, and clonal propagation.

As discussed earlier, the idea that BMP4 can drive hESCs to trophoblast has been controversial (31), despite evidence that both mouse ESCs and hESCs have the potential to differentiate along extraembryonic lineages under appropriate culture conditions (9–24). Moreover, recent evidence suggests that BMP signaling has a role in ensuring the correct development of the trophoblast lineage in preimplantation mouse embryos (59, 60) and that, by the 16-cell morula stage, only the outer cells are fully equipped to respond to signals initiated by BMP4 and related ligands, such as BMP7 (59). Conceivably, human PSCBP lines are analogous to these outer cells. Their phenotype has been molded by brief BMP exposure, and they remain pluripotent yet can transform to trophoblast as soon as the pluripotent network begins to be down-regulated.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care.

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under Protocol 7170.

Pluripotent Stem Cell Culture.

Human H1 (WA01) and H9 (WA09) ESCs were from the WiCell Research Institute, whereas the iPSC line was derived from human umbilical cord fibroblasts reprogrammed with five factors and TP53 shRNA by using episomal plasmid transfection (61) as described by Lee et al. (62). For routine maintenance, all cell lines were cultured in six-well culture plates (Nunc) coated with Matrigel (BD Bioscience) in the defined mTeSR1 medium, containing FGF2 at 100 ng/mL and 0.6 ng of TGF-β at 0.6 ng/mL (STEMCELL Technologies) (63), The medium in all wells was changed daily. Cells were passaged at a 1:6 ratio every 5–6 d by using dispase (1 mg/mL; STEMCELL Technologies) for 7 min at 37 °C, followed by breakage into small clumps with the Stempro EZpassage (InVitrogen) cutting tool.

Establishing Self-Renewing PSCBP Colonies.

To establish the BP self-renewing colonies (Fig. 1A), H1 cell, H9 cell, hESC, and iPSC colonies were subcultured to provide a transfer of ∼2.4 × 104 cells per square centimeter. On the following day, the culture medium was changed from the defined mTeSR1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies) to the standard medium for hESCs (64, 65), which had been conditioned by a monolayer of γ-irradiated MEF feeder cells (21, 66) containing FGF2 (4 ng/mL). After a further 24 h, the medium was changed to one lacking FGF2 but containing BMP4 (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems), the ALK4/5/7 inhibitor A83-01 (1 μM; Tocris Bioscience), and the FGF2-signaling inhibitor PD173074 (0.1 μM; Sigma–Aldrich) in hESC basal medium not conditioned with MEF feeder cells. Control cultures continued to be grown in the presence of FGF2 and in the absence of BAP. Following this exposure to BMP4 and inhibitors, the culture medium was changed to MEF-CM with FGF2 (10 ng/mL). Culture medium was replenished daily for an additional 2–4 d. On either day 5 or 6, cells were dispersed with TrypLE Express (Gibco) for 3–4 min or with Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (STEMCELL Technologies) for 6–7 min at 37 °C and transferred to 0.1% gelatin-coated culture dishes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Aihua Dai, Dr. Alexander Jurkevich, and Ms. Yuchen Tian for experimental contributions and Mr. Dennis Reith for his editorial assistance. We also thank Drs. Yun Lian and Jinchun Zhou (University of Texas Southwestern Microarray Core Laboratory) for performing the microarray analysis and for their extensive discussion of the microarray data, and the reviewers for their helpful insights. This work was supported by NIH Grants R01HD067759 and R01HD077108.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE62065).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1504778112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brons IG, et al. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448(7150):191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesar PJ, et al. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7150):196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greber B, et al. Conserved and divergent roles of FGF signaling in mouse epiblast stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(3):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallier L, et al. Early cell fate decisions of human embryonic stem cells and mouse epiblast stem cells are controlled by the same signalling pathways. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e6082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vallier L, Alexander M, Pedersen RA. Activin/Nodal and FGF pathways cooperate to maintain pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 19):4495–4509. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallier L, et al. Signaling pathways controlling pluripotency and early cell fate decisions of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(11):2655–2666. doi: 10.1002/stem.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu RH, et al. NANOG is a direct target of TGFbeta/activin-mediated SMAD signaling in human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(2):196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenke-Layland K, et al. Collagen IV induces trophoectoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(6):1529–1538. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He S, Pant D, Schiffmacher A, Meece A, Keefer CL. Lymphoid enhancer factor 1-mediated Wnt signaling promotes the initiation of trophoblast lineage differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(4):842–849. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi Y, et al. BMP4 induction of trophoblast from mouse embryonic stem cells in defined culture conditions on laminin. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2010;46(5):416–430. doi: 10.1007/s11626-009-9266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harun R, et al. Cytotrophoblast stem cell lines derived from human embryonic stem cells and their capacity to mimic invasive implantation events. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(6):1349–1358. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerami-Naini B, et al. Trophoblast differentiation in embryoid bodies derived from human embryonic stem cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145(4):1517–1524. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen G, et al. Trophoblast differentiation defect in human embryonic stem cells lacking PIG-A and GPI-anchored cell-surface proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(4):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas GC, VandeVoort CA, Kumar P, Chang TC, Golos TG. Trophoblast stem cells: Models for investigating trophectoderm differentiation and placental development. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(3):228–240. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drukker M, et al. Isolation of primitive endoderm, mesoderm, vascular endothelial and trophoblast progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):531–542. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, et al. BMP4-directed trophoblast differentiation of human embryonic stem cells is mediated through a ΔNp63+ cytotrophoblast stem cell state. Development. 2013;140(19):3965–3976. doi: 10.1242/dev.092155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchand M, et al. Transcriptomic signature of trophoblast differentiation in a human embryonic stem cell model. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(6):1258–1271. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.086413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz LC, et al. Human embryonic stem cells as models for trophoblast differentiation. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S10–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudheer S, Bhushan R, Fauler B, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. FGF inhibition directs BMP4-mediated differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to syncytiotrophoblast. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(16):2987–3000. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das P, et al. Effects of fgf2 and oxygen in the bmp4-driven differentiation of trophoblast from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2007;1(1):61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erb TM, et al. Paracrine and epigenetic control of trophectoderm differentiation from human embryonic stem cells: The role of bone morphogenic protein 4 and histone deacetylases. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20(9):1601–1614. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu RH, et al. BMP4 initiates human embryonic stem cell differentiation to trophoblast. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(12):1261–1264. doi: 10.1038/nbt761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtner B, Knaus P, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. BMP10 as a potent inducer of trophoblast differentiation in human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(38):9789–9802. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amita M, et al. Complete and unidirectional conversion of human embryonic stem cells to trophoblast by BMP4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(13):E1212–E1221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303094110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telugu BP, et al. Comparison of extravillous trophoblast cells derived from human embryonic stem cells and from first trimester human placentas. Placenta. 2013;34(7):536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai Q, et al. Dissecting the first transcriptional divergence during human embryonic development. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8(1):150–162. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9301-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115(3):281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassani SN, et al. Inhibition of TGFβ signaling promotes ground state pluripotency. Stem Cell Rev. 2014;10(1):16–30. doi: 10.1007/s12015-013-9473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernardo AS, et al. BRACHYURY and CDX2 mediate BMP-induced differentiation of human and mouse pluripotent stem cells into embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(2):144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts RM, et al. Differentiation of trophoblast cells from human embryonic stem cells: to be or not to be? Reproduction. 2014;147(5):D1–D12. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig T, A Thompson J. 2007. Defined, feeder-independent medium for human embryonic stem cell culture. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol Chapter 1:Unit 1C.2.

- 33.Chan EM, Yates F, Boyer LF, Schlaeger TM, Daley GQ. Enhanced plating efficiency of trypsin-adapted human embryonic stem cells is reversible and independent of trisomy 12/17. Cloning Stem Cells. 2008;10(1):107–118. doi: 10.1089/clo.2007.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez L, et al. Maintenance of human embryonic stem cells in media conditioned by human mesenchymal stem cells obviates the requirement of exogenous basic fibroblast growth factor supplementation. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2012;18(5):387–396. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2011.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka S. Derivation and culture of mouse trophoblast stem cells in vitro. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;329:35–44. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-037-5:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J. Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science. 1998;282(5396):2072–2075. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller FJ, et al. A bioinformatic assay for pluripotency in human cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts RM, Fisher SJ. Trophoblast stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(3):412–421. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kidder BL, Palmer S. Examination of transcriptional networks reveals an important role for TCFAP2C, SMARCA4, and EOMES in trophoblast stem cell maintenance. Genome Res. 2010;20(4):458–472. doi: 10.1101/gr.101469.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ralston A, et al. Gata3 regulates trophoblast development downstream of Tead4 and in parallel to Cdx2. Development. 2010;137(3):395–403. doi: 10.1242/dev.038828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y, Blair K, Smith A. Robust self-renewal of rat embryonic stem cells requires fine-tuning of glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition. Stem Cell Rev. 2013;1(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong J, et al. A focused microarray for screening rat embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(3):431–443. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajendran G, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase C signaling maintains rat embryonic stem cell pluripotency. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(34):24351–24362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niakan KK, Eggan K. Analysis of human embryos from zygote to blastocyst reveals distinct gene expression patterns relative to the mouse. Dev Biol. 2013;375(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berg DK, et al. Trophectoderm lineage determination in cattle. Dev Cell. 2011;20(2):244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, et al. Cross-regulation of the Nanog and Cdx2 promoters. Cell Res. 2009;19(9):1052–1061. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Surani A, Tischler J. Stem cells: A sporadic super state. Nature. 2012;487(7405):43–45. doi: 10.1038/487043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh AM, Hamazaki T, Hankowski KE, Terada N. A heterogeneous expression pattern for Nanog in embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(10):2534–2542. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macfarlan TS, et al. Embryonic stem cell potency fluctuates with endogenous retrovirus activity. Nature. 2012;487(7405):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature11244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torres-Padilla ME, Parfitt DE, Kouzarides T, Zernicka-Goetz M. Histone arginine methylation regulates pluripotency in the early mouse embryo. Nature. 2007;445(7124):214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature05458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abad M, et al. Reprogramming in vivo produces teratomas and iPS cells with totipotency features. Nature. 2013;502(7471):340–345. doi: 10.1038/nature12586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benirschke K. Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Regelson W. Have we found the “definitive cancer biomarker”? The diagnostic and therapeutic implications of human chorionic gonadotropin-beta expression as a key to malignancy. Cancer. 1995;76(8):1299–1301. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951015)76:8<1299::aid-cncr2820760802>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butler SA, Iles RK. Ectopic human chorionic gonadotropin beta secretion by epithelial tumors and human chorionic gonadotropin beta-induced apoptosis in Kaposi’s sarcoma: Is there a connection? Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(13):4666–4673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenman UH, Alfthan H, Hotakainen K. Human chorionic gonadotropin in cancer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(7):549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Itinteang T, et al. A placental chorionic villous mesenchymal core cellular origin for infantile haemangioma. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(10):870–874. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark BZ, Beriwal S, Dabbs DJ, Bhargava R. Semiquantitative GATA-3 immunoreactivity in breast, bladder, gynecologic tract, and other cytokeratin 7-positive carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142(1):64–71. doi: 10.1309/AJCP8H2VBDSCIOBF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang P, et al. Abnormal oxidative stress responses in fibroblasts from preeclampsia infants. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Graham SJ, et al. BMP signalling regulates the pre-implantation development of extra-embryonic cell lineages in the mouse embryo. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5667. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chu GC, Dunn NR, Anderson DC, Oxburgh L, Robertson EJ. Differential requirements for Smad4 in TGFbeta-dependent patterning of the early mouse embryo. Development. 2004;131(15):3501–3512. doi: 10.1242/dev.01248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okita K, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8(5):409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee K, et al. Engraftment of human iPS cells and allogeneic porcine cells into pigs with inactivated RAG2 and accompanying severe combined immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(20):7260–7265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406376111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ludwig TE, et al. Feeder-independent culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3(8):637–646. doi: 10.1038/nmeth902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amit M, et al. Clonally derived human embryonic stem cell lines maintain pluripotency and proliferative potential for prolonged periods of culture. Dev Biol. 2000;227(2):271–278. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ezashi T, Das P, Roberts RM. Low O2 tensions and the prevention of differentiation of hES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(13):4783–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501283102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu RH. In vitro induction of trophoblast from human embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Med. 2006;121:189–202. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-983-4:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.