The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) has the following goal: “to provide clear descriptions of diagnostic categories in order to enable clinicians and investigators to diagnose, communicate about, study, and treat people with various mental disorders.” The DSM-IV also includes specifiers for mood disorders that are intended to increase diagnostic specificity and create homogeneous subgroups, drive treatment selection, and improve the prediction of prognosis. With postpartum onset is a specifier with two requirements: 1) a time criterion (onset of episode within 4 weeks after birth), and 2) application to the current or most recent episode of four diagnoses (major depressive disorder; major depressive, manic, or mixed episode in bipolar I or II disorder; or brief psychotic disorder). However, the term postpartum depression has been used to describe a broad variety of childbearing-related mood episodes not included in the DSM-IV definition. Gaynes et al. (2005) used an expanded concept of perinatal depression (during pregnancy through one year postpartum) in their report (commissioned by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) to inform national policy. From a public health perspective, women, families and communities suffer regardless of when the maternal episode begins.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the DSM-IV definition of with postpartum onset and challenges in its clinical and research application. Our goal is to frame the discussion about the specifier as revisions of the DSM and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes are considered. We focus on major depressive disorder (MDD) to highlight the ways in which the definition of the postpartum onset specifier might be modified.

Time considerations

The DSM-IV sets 4 weeks post-birth as the delimiter for with postpartum onset; in contrast, the ICD-10 classifies mental disorders as associated with the puerperium if they begin within 6 weeks after birth. An international expert panel convened at Satra Bruk, Sweden, recommended 3 months as the time frame for specifying postpartum onset (Elliott 2000). This decision was influenced by classic epidemiologic studies conducted by R.E. Kendell and colleagues in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Kendell et al. (1987) found an increased risk for admission for any psychiatric illness from birth through 90 days. The excess of admissions after childbirth was far greater than the deficit of admissions during pregnancy.

Munk-Olsen et al. (2006) performed an epidemiologic investigation of a reproductive-aged population-based cohort of women and men with the first lifetime onset of psychiatric illness from their infant’s birth to 12 months post-birth. Similar to Kendell et al. (1987), they found that the risk of psychiatric admission or outpatient contact for the period of birth through 3 months (precisely, through less than 4 months) was significantly higher compared to women who became parents 11 to 12 months before. Munk-Olsen et al. (2006) also provided data for increased risk specifically for MDD, which was significantly elevated for 5 months after birth. The relative risk for MDD from 0 to 30 days postpartum was 2.79; 31–60 days, 3.53; and 3 to 5 months, 2.08. Both investigative teams observed that pregnancy was a time of decreased risk for incident episodes for women. No increase in psychiatric illness was observed among fathers of infants at any time during or following their partner’s pregnancy.

These two epidemiologic studies with different populations and comparison groups converge on a significantly elevated overall risk of 1.7 (for first time psychiatric admission or contact; Munk-Olsen et al. 2006) to 3.8 (for all admissions; Kendell et al. 1987) within 90 days of childbirth. These observations raise the question of whether the postpartum onset specifier should be expanded to 3 months post-birth. Alternatively, disease-specific risk periods could be defined, such as 5 months postpartum for MDD (Munk-Olsen et al. 2006). Application of disease-specific time frames may be premature given limited data and the added complexity for implementation. Finally, although the most frequent episodes identified in hospitalized women in both perinatal epidemiological studies were mood disorders, the incidence of anxiety disorders (such as obsessive compulsive and panic; Ross and McLean 2006) and schizophrenia (Munk-Olsen et al. 2006) are increased during the post-birth period. Expanding the postpartum onset specifier to a broader group of diagnoses will facilitate identification for research purposes.

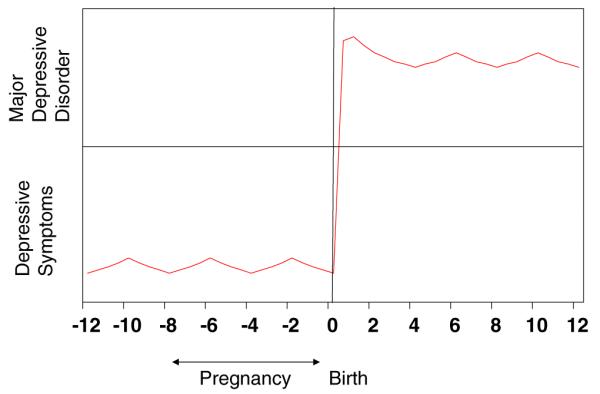

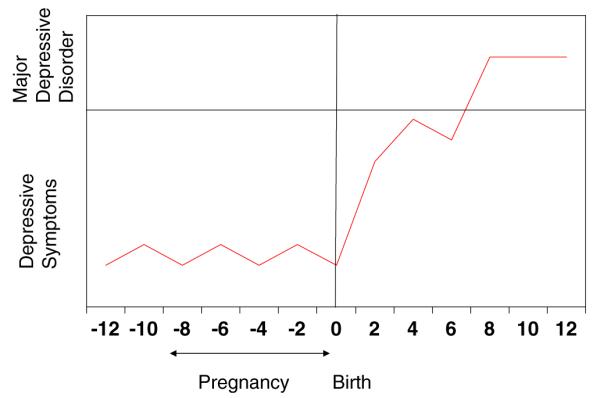

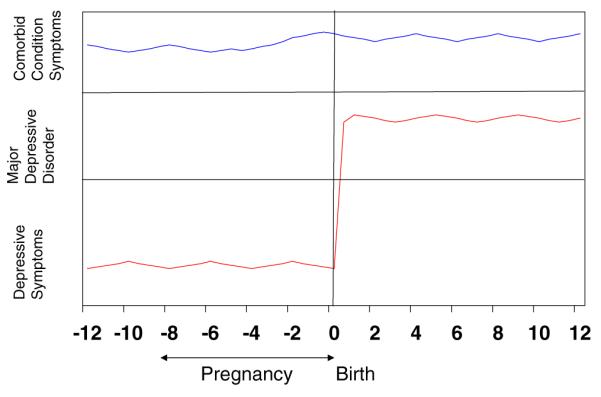

Many challenges are inherent when applying the postpartum onset specifier to MDD in clinical practice. If the symptom course follows the pattern in Fig. 1, the episode meets full criteria for MDD before 4 weeks postpartum and clearly fits the DSM-IV definition. In Fig. 2, the symptoms increase within the 4 week post-birth period, but do not meet full criteria for MDD until 7 months postpartum. This type of symptom trajectory challenges the definition of “within 4 weeks after birth.” Does within 4 weeks refer to the onset of symptoms that evolve into an episode of MDD or to onset of the full syndrome? The pattern in Fig. 2 would not allow the diagnosis of MDD with postpartum onset until 7 months postpartum. Before 7 months, the patient might be described as having minor depression with postpartum onset. Minor depression is included in the DSM-IV Appendix as an episode of sad mood or loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities and at least two but less than five additional symptoms from the criterion set for MDD. The symptoms must cause distress or impairment in function. In DSM-IV, individuals whose presentation meets these criteria would be diagnosed as having adjustment disorder with depressed mood if the symptoms occurred in response to a psychosocial stressor. Should the pattern in Fig. 2 before 7 months be called minor depression with postpartum onset, which is not in accord with DSM-IV but often included in postpartum depression incidence figures (as in Gaynes et al. 2005). Or should it be labeled adjustment disorder with depressed mood, since childbirth is certainly a major psychosocial stressor?

Fig. 1.

Classical depression with postpartum onset

Fig. 2.

Full syndrome of depression onsets beyond 4 weeks postpartum

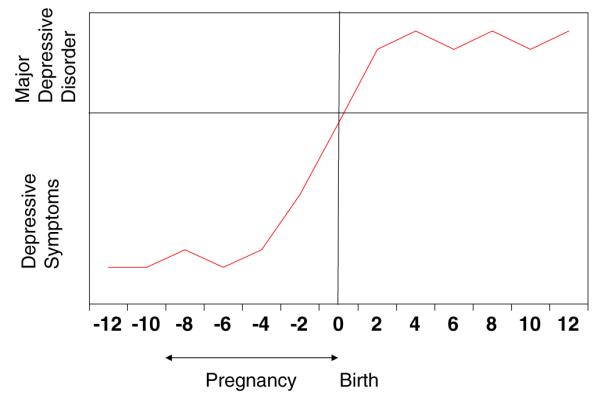

Figure 3 displays antenatal symptom onset with progression to full criteria for MDD within 4 weeks after delivery. This pattern is strikingly similar to the pattern of depressive symptoms elicited by a laboratory simulation of childbearing. Bloch et al. (2000) studied two groups of women: those with a history of MDD with postpartum onset and women with no history of depression. The investigators simulated perinatal hormone exposure by inducing a hypogonadal state with leuprolide, adding back supraphysiologic doses of estradiol and progesterone for eight weeks, and then withdrawing both steroids under double-blind conditions. Five of eight women with previous postpartum MDD developed symptoms at the end of the add-back phase (which simulated the sustained elevation of gonadal steroids of pregnancy) which peaked in intensity in the withdrawal (simulated postpartum) phase. Women with no previous depressive episodes were unaffected. Does symptom onset during pregnancy negate the with postpartum onset specifier? What if the full episode of MDD does not evolve until after birth, as in Fig. 3? The proximal bound of time for the operational definition of postpartum onset must be reconsidered for DSM-V.

Fig. 3.

Antenatal onset of depressive symptoms

Diagnostic considerations

The diagnostic entities most frequently observed after birth in both the Kendell et al. (1987) and Munk-Olsen et al. (2006) studies were major mood disorders, with a particular risk for bipolar disorder. Munk-Olsen et al observed highly significant relative risks of 23.33 in the first 30 days and 6.30 in the 31–60 days after birth for bipolar disorder. Kendell et al reported an RR of 21.7 for admission with psychosis (primarily bipolar disorder) within 30 days of birth. According to the DSM-IV, MDD with postpartum onset can be used to describe an episode of MDD within the longitudinal context of bipolar affective disorder. However, the term postpartum depression is frequently used to describe depressive episodes in any recently delivered woman. We urge careful diagnostic assessment with a focus on unipolar-bipolar differentiation to drive evidence-based treatment.

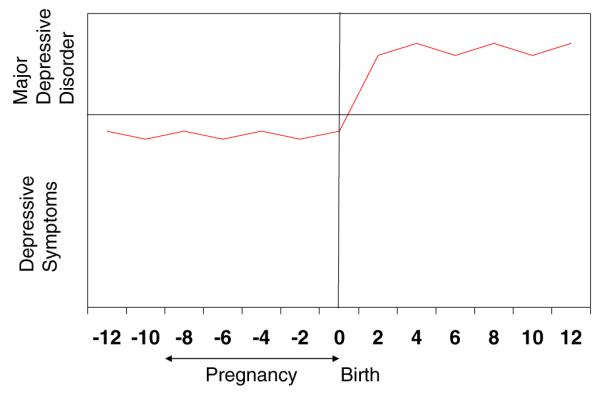

Figure 4 presents the situation of dysthymic disorder with the emergence of MDD within 4 weeks after birth. The syndromal MDD began after birth, but the onset of the majority of the depressive symptoms and impairment were more than two years prior to birth. Does this MDD with comorbid dysthymia qualify as MDD with postpartum onset?

Fig. 4.

Pre-existing dysthymic disorder

In Fig. 5, we consider other comorbid conditions. If the condition is obsessive compulsive disorder, the emergent episode of MDD within 4 weeks of birth would qualify for the with postpartum onset specifier. What if the comorbid condition is schizophrenia? According to the DSM-IV, MDD during the active or residual phase of schizophrenia or must be labeled as Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. If the woman has full remission of psychosis, is stable on antipsychotic medication throughout pregnancy and post-birth, and develops MDD within four weeks after birth, her symptom pattern fits the MDD with postpartum onset specifier. With accumulating research evidence of the neuromodulatory and neuroprotective activity of estrogens in women with schizophrenia, evaluation of the DSM-IV diagnostic restrictions in this context is warranted.

Fig. 5.

Comorbid diagnoses

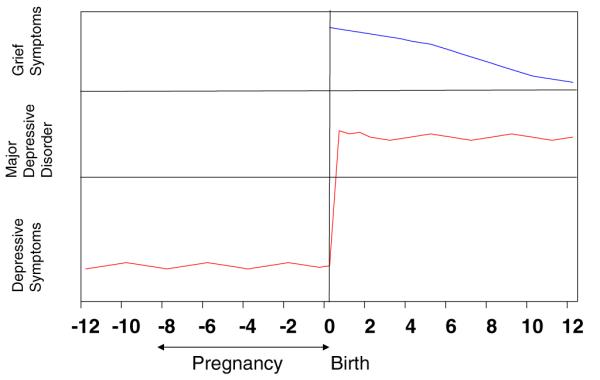

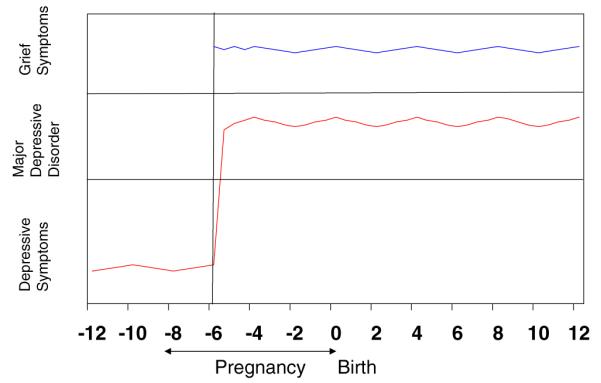

Kendell et al. (1987) reported that a factor significantly associated with postpartum psychiatric admission was infant death. In Fig. 6, the neurobiological milieu of the post-birth period is superimposed upon grief. If the mother experiences a stillbirth but has an episode consistent with MDD within 4 weeks of the fetal demise, does she have MDD with postpartum onset? Or should this diagnosis be assigned after evaluation of the course of the grief process? Figure 7 adds another consideration that is rarely discussed in the perinatal literature: how long must a pregnancy last to qualify for the with postpartum onset specifier? What if a woman has a miscarriage at the end of the first trimester and develops an episode of MDD within four weeks of the fetal loss?

Fig. 6.

Still birth and depression

Fig. 7.

Fetal loss and depression

We return to one of the goals of the DSM-IV: to define diagnostic categories to enable investigators to define populations for study. The potential contributions of perinatal research to the field of mental health have yet to be realized. The dramatic events of women’s reproductive lives provide an unparalleled opportunity for the study of etiologic factors. Identification of neural mechanisms in women with normal compared to impaired maternal mood regulation may inform development of new treatments. Alterations in the intrauterine climate associated with psychiatric disorders, such as changes in maternal hormones and monoamine function, affect the offspring’s neurobehavioral function and overall health into adulthood, termed fetal programming. The relationship between maternal mental illness and early childhood problems in offspring is a potentially modifiable sequence that begins during pregnancy. Carefully considered DSM-V nomenclature will strengthen our ability to reap this potential.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Dr. Wisner received a donation of active and placebo patches from Novogyne for an Nimit funded trial. Drs. Moses-Kolko and Sit have no conflicts.

Contributor Information

Katherine L. Wisner, Departments of Psychiatry, Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Epidemiology, and Women’s Studies, Women’s Behavioral HealthCARE, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

Eydie L. Moses-Kolko, Women’s Behavioral HealthCARE, Department of Psychiatry, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; MosesEL@upmc.edu

Dorothy K. Y. Sit, Women’s Behavioral HealthCARE, Department of Psychiatry, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; SitDK@upmc.edu

References

- Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatr. 2000;157(6):924–930. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S. Report on the satra bruk workshop on classification of postnatal mental disorders on november 7–10, 1999, convened by Birgitta Wickberg, Philip Hwang and John Cox with the support of Allmanna Barhuset represented by Marina Gronros. Arch Wom Ment Health. 2000;3:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes B, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr K, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. In: A. P. N. 05-E006-2, editor. Evidence report/technology assessment. Vol. 119. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville: 2005. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. [erratum appears in br j psychiatry 1987 jul;151:135] Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662–673. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Laursen T, Pederson C, Mors O, Mortensen P. New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2582–2589. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, McLean LM. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(8):1285–1298. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]