Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pulmonary contusion (PC) is a common, potentially lethal injury that results in the priming for exaggerated responses to subsequent immune challenge such as an infection (second hit). We hypothesize a PC-induced complement (C) activation participates in the priming effect for a second hit.

METHODS

Male, 8 weeks to 9 weeks, C57BL/6 mice (wild-type, C5−/−) underwent blunt chest trauma resulting in PC. At 3 hours/24 hours after injury, the inflammatory response was measured in tissue, serum, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). The thrombin inhibitor, hirudin, was used to determine if injury-induced thrombin participated in the activation of C. Injury-primed responses were tested by challenging injured mice with bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) as a second hit. Inflammatory responses were assessed at 4 hours after LPS challenge. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni multiple comparison posttest (significance, p ≤ 0.05). Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

We found significantly increased levels of C5a in the BAL of injured animals as early as 24 hours, persisting for up to 72 hours after injury. Hirudin-treated injured mice had significantly decreased levels of thrombin in the BAL that correlated with reduced C5a levels. Injured mice challenged with intratracheal (IT) LPS had increased C5a and inflammatory response. Conversely, inhibition of C5a or its receptor, C5aR, before LPS challenge correlated with decreased inflammatory responses; C5a-deficient mice showed a similar loss of primed response to LPS challenge.

CONCLUSION

Complement C5a levels in the BAL are increased over several days after PC. Premorbid inhibition of thrombin markedly decreases C5a levels after PC, suggesting that thrombin-induced C activation is the major pathway of activation after PC. Similarly, inhibition of C5a after PC will decrease injury-primed responses to LPS stimulation. Our findings suggest cross-talk between the coagulation and complement systems that induce immune priming after PC.

Keywords: Pulmonary contusion, complement C5a, second hit, immune priming, mice

It is clinically recognized that significant traumatic injury seems to prime the immune system for an exaggerated response to subsequent infectious challenge (the “second hit”) with the lung as a particularly vulnerable organ.1 The second hit response is linked to multiple-organ dysfunction and death, and previous studies have implicated this response to exaggerated Toll-like receptor (TLR)–mediated signaling.2,3 We and others have previously shown a priming effect of injury on TLR4-induced expression of inflammatory proteins.2–4 However, injury-induced mediators of these enhanced or primed TLR responses are not yet well defined.

Complement is a major component of innate immunity and is activated via the classical, alternative, and/or mannose-binding pathways that converge at C3; however, alternative activation pathways have been described.5 The major effector protein of complement activation is the anaphylatoxin, C5a. Acting through the receptor C5aR, C5a elicits a variety of pro-inflammatory activities including cellular activation, leukocyte chemotaxis, and alterations of apoptosis.6 The role of C5a in injury has been the focus of numerous studies.7–9 Models of ischemia and reperfusion injuries showed that inflammatory responses required C5a, with inhibition of either C5 or C3 being protective.10–12 Similarly, animal models of noninfectious lung injury demonstrate that complement activation and C5a is an integral component of the inflammatory response.13,14 In septic and injured humans, levels of complement activation products are elevated and have been correlated with the onset of infectious morbidity and mortality.9

Recent evidence indicates the presence of extensive “cross-talk” between the complement and TLR signaling pathways.15 Such molecular interplay could result in synergistic or antagonistic interactions. Indeed, synergism between C5a and TLR4 has been described, resulting in exaggerated TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses.16–20 Our previous studies in an animal model of isolated blunt chest trauma showed that this injury would prime effector cells of innate immunity for a second hit and observed the exaggerated response to LPS, when administered to the lung after injury.4 In this report, we tested the hypothesis that C5a is induced by traumatic lung injury and that injury priming for a second hit of LPS is dependent on C5a.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics and Selection

Patient study procedures were approved by the institutional review board (#BG03-081). Patients were identified prospectively during a 12-month period. We included patients who required mechanical ventilation and were diagnosed with a unilateral or bilateral pulmonary contusion (PC) on admission chest computed tomography. Successive bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens were obtained at the times indicated. Lung contusion volume was determined as previously described.21 Outcome metrics were collected, including the onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) within the first 72 hours of admission and pneumonia. ARDS was defined as PaO2/FIO2 ratio less than 200 with diffuse bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph with no evidence of congestive heart failure.22 Pneumonia was diagnosed by BAL and defined as greater than 105 CFU/mL. Uninjured, healthy volunteers were used as controls.

Animals

Male, age-matched (8–9 weeks) C57/BL6 (wild-type [WT]), C3-deficient (C3−/−) and C5-deficient (C5−/−) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Tissue, serum, and BAL were obtained at the times indicated. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animal injury model

PC was induced using the cortical contusion impactor as described previously.23 Briefly, mice were anesthetized and positioned left lateral decubitus and during inspiration, and the right chest was struck with the cortical contusion impactor along the posterior axillary line, 1 cm above the costal margin.

Second-Hit Model

The second-hit mouse model used was previously described.4 Briefly, at 24 hours following PC, 50 μg of LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected into the trachea (IT). Control animals were (1) injured and received IT phosphate-buffered saline alone or (2) received IT LPS without previous injury.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

Patients

BAL was performed using a clean inline suction catheter at the times indicated. Normal saline (3 times 30 mL, 37°C) was instilled and collected in a Lukens specimen trap. BAL samples were separated into cells and supernatant by low-speed centrifugation.

Animals

BAL was performed by cannulation of the trachea as described previously.4 BAL supernatants were collected and stored at −70°C until use. The cell pellet was counted and differentiated as previously described.23,24

Injury and inflammatory mediator measurements

Complement, cytokine, chemokine, and thrombin activity measurements, C5a, interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-10, CXCL1 and thrombin activity, were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or fluorometric thrombin activity assay (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Samples were assayed in duplicate.

Histopathology

Lung specimens were fixed in 10% formalin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (slides, original magnification 20×) were evaluated and graded for the presence of interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate, intra-alveolar hemorrhage, and pulmonary septal edema as described previously.23,24

Neutralization/Inhibition Studies

Complement C5a activity was neutralized using α-C5a antibody (R&D Systems) or C5a receptor antagonist (C5aRa, AnaSpec). Thrombin activity was inhibited using hirudin (lepirudin [Refludan], Bayer, Wayne, NJ). At 20 minutes before injury, α-C5a (45 μg) was given intraperitoneally (IP) or intravenously. At 1 hour before and at 30 minutes after injury, hirudin (2 mg/kg) was given IP. At 45 minutes before the second hit, α-C5a (45 μg) or C5aRa (2 mg/kg) was given IP.

Statistical Analysis

At the indicated times, serum and BAL samples were collected after death. Data are reported using GraphPad Prism (version 4.03, San Diego, CA) and expressed as the mean ± SEM of independent observations as indicated in the figures. Student’s t test and/or one-way analysis of variance with multiple comparison post test (Bonferroni) was used to compare the means between experimental groups as indicated. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Patients With PC Show Sustained BAL Levels of C5a After Injury

As shown in Figure 1A, we found significant and sustained levels of C5a in the BAL of patients with PC. C5a levels were increased within 24 hours of injury and remained higher than BAL levels observed in normal healthy controls throughout the 5-day observation period. In patients at risk for developing ARDS with greater than 24% contused lung,21 complement C5a BAL levels at 24 hours after injury were significantly increased, and of those, patients who developed pneumonia showed significantly higher C5 levels than those without infection (Fig. 1B). These results show sustained C5a activation in the BAL from PC patients. Furthermore, C5a levels are significantly increased with the size of contusion and/or in patients with pneumonia, suggesting an association between complement activation and the onset of organ dysfunction and infectious morbidity.

Figure 1.

Patients with PC show sustained BAL levels of C5a after injury. C5a levels in the BAL from uninjured and injured patients with PC were measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. A, BALs from PC patients show increased C5a levels compared with BAL levels from healthy, uninjured controls (n = 4 per group). B, At 24 hours after injury, patients with PC greater than 24% (n = 4) showed significantly decreased C5a BAL levels compared with patients with PC greater than 24% (n = 6), while patients with PC greater than 24% and pneumonia (pc >24%pn, n = 4) showed significantly increased C5a BAL levels (significance, *p ≤ 0.05).

The Model of PC Shows Sustained BAL Levels of C5a and C5a-Dependent Inflammatory Response to Injury

Given our findings in humans, we sought to determine the role of C5a in a mouse PC model. We and others have previously shown that the injury response to PC, in addition to physical lung dysfunction, has many attributes similar to innate immune inflammatory responses.25,26 As shown in Figure 2A, we found significant and sustained increases in C5a levels in the BAL of injured mice. Similar to humans, C5a levels were increased within 24 hours of PC and remained significantly increased for up to 72 hours after injury. Using C5a−/− mice, we determined inflammatory responses to PC that were dependent on C5a. As shown in Figure 2B, we found that poly-morphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) recruitment to the injured lung is, at least in part, dependent on complement activation. C5a−/− mice or WT mice treated with α-C5a before injury show significantly decreased levels of PMN. Consistent with this observation, we also found significantly decreased serum levels of CXCL1 and IL-6 and observed a decrease in lung histopathology in the absence of C5a (Fig. 2C and D, respectively) In contrast, IL-10 serum levels were unchanged by injury in WT or C5a−/− mice (data not shown).

Figure 2.

A mouse model of PC shows sustained BAL levels of C5a after injury and C5a-dependent injury and inflammatory responses. C5a and PMN (24 hours, BAL), CXCL1, and IL-6 levels (3 hours, serum) from uninjured and injured mice measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. A, BALs from WT injured mice show increased C5a levels compared with BAL levels from uninjured controls (n = 6 per group). B, C5-deficient (C5−/−, open bars) injured mice show significantly decreased PMN levels compared with WT injured mice (solid bars) (n = 6 per group). WT injured mice were treated IP or intravenously (n = 4) with α-C5a as described in the Materials and Methods section and show significantly decreased PMN levels compared with untreated injured WT mice. C, Serum levels of inflammatory mediators in uninjured (n = 3 per group) and injured (n = 5 per group) WT or C5−/− mice were compared. CXCL1 and IL-6 (10-fold difference in injured scale, left panel) were increased in injured mice compared with uninjured mice and was significantly decreased in C5−/− injured mice. (significance *p ≤ 0.05; **p < 0.001; n.s., no significant difference). D, Uninjured and injured lungs from WT and C5-deficient mice were formalin fixed, stained, and analyzed by an experienced pathologist. Lung sections of the contusion are shown (original magnification, 20×) at 24 hours after injury. Hemorrhage is evident in all injuries (right panels). Neutrophil infiltration is reduced in C5−/− mice compared with WT. Specimens shown are representative of lung injuries in at least three animals per genotype.

C3-Independent Complement Activation After PC

Complement activation pathways converge at C3 to form a C5 convertase that generates C5a. To test for a role for C3 in complement activation after PC, we measured C5a in the BAL of C3−/− injured mice. As shown in Figure 3, we found comparable levels of C5a in the BAL of WT and C3−/− mice after injury. As expected, C5−/− mice did not have C5a in the BAL. These data suggest that alternative pathways of complement activation play a major role in C5a generation after PC.

Figure 3.

C5a release into the alveolar space after PC seems to be C3 independent. C5a levels in the BAL from uninjured and injured WT (black) and C3-deficient (C3−/−, gray) mice (24 hours, n = 5 per group) were measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. Levels of C5a in the BAL from injured C3−/− mice were similar to C5a levels in injured WT mice. For comparison, C5a levels in C5−/− mice are shown (open bars, left panel, note different scale, n = 4 per group) and show low C5a BAL levels with or without injury. (n.s., no significant difference).

Mechanism of Complement Activation After PC

Recent studies suggest that thrombin can activate complement C5a after injury.27,28 To determine if thrombin participates in complement activation after PC, we measured thrombin levels in the BAL and determined C5a levels in the BAL of injured mice treated with the thrombin inhibitor, hirudin (Fig. 4). At 3 hours after PC, we observed thrombin activity in the BAL of injured mice that was decreased in the BAL of hirudin-treated injured mice (Fig. 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, C5a levels were decreased in the BAL of hirudin-treated WT and C3−/− injured mice.

Figure 4.

Thrombin activity is inhibited by hirudin treatment and decreases C5a levels in the BAL of injured mice. Injured WT mice (black) were treated with hirudin, and thrombin activity and C5a were measured in the BAL as described in the Materials and Methods section. A, At 3 hours after injury, thrombin activity is significantly increased in the BAL from injured mice and is decreased to uninjured levels with inhibition by hirudin treatment of injured mice. B, Hirudin treatment also decreased C5a levels in the BAL of injured WT or C3-deficient (C3−/−) mice at 24 hours after injury (n = 5 per group, significance *p < 0.001).

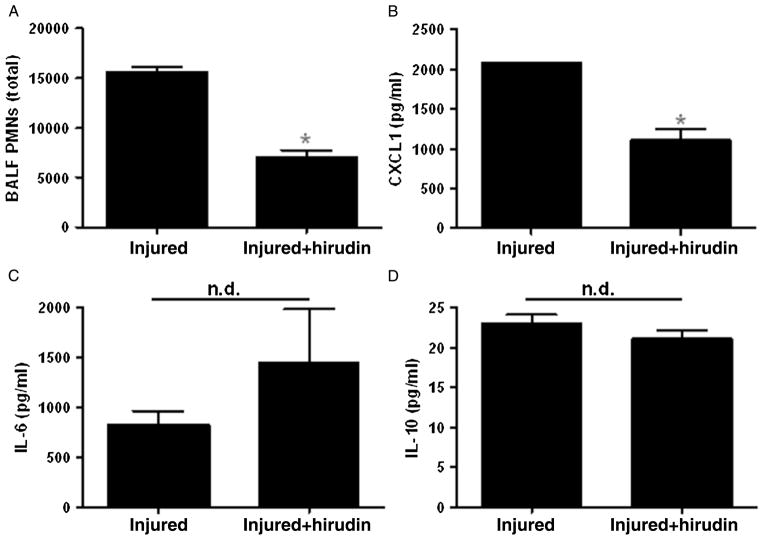

We also determined whether the inhibition of thrombin inhibited inflammatory responses after injury. As shown in Figure 5, we found that both PMN and CXCL1 levels were decreased in hirudin-treated injured mice; however, injury-induced IL-6 and IL-10 levels were unchanged with thrombin inhibition. Taken together, these results support a model of localized inflammatory response (CXCL1 and PMN infiltration) that is dependent on thrombin-activated C5a in the injured lung.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of thrombin activity decreases PMN and CXCL1 levels in injured mice. Injured WT mice were treated with hirudin and PMN, and inflammatory mediator levels were measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. A, Hirudin treatment significantly decreases PMN in the BAL at 24 hours after injury. B, Hirudin treatment also significantly decreases CXCL1 levels in the serum at 3 hours after injury. Serum levels of IL-6 (C) and IL-10 (D) are not affected by hirudin treatment (n = 6 per group; significance *p < 0.0001; n.d., no difference).

C5a Mediates Priming

Synergism between C5a- and TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses has been described.16–20 Since PC patients at higher risk for ARDS and pneumonia showed significantly higher levels of C5a, we used our mouse PC model to determine whether C5a plays a role on the second hit. We hypothesized that elevated levels of C5a after PC participate in the priming to a second hit of LPS. As we had previously observed, injury increased PMN in the BAL after a second hit (LPS) when compared with LPS without injury (Fig. 6A). We further established that this increased PMN was dependent on C5a, since no significant difference was seen in PMN levels in LPS without injury when C5a is blocked (α-C5a or C5aRa treated) or absent (C5a−/− mice).

Figure 6.

C5a mediates a primed inflammatory response after PC. As described in the Materials and Methods section, injured WT mice were treated without or with α-C5a or C5aRa before LPS as a second hit; BAL as well as serum and tissue samples were obtained at 4 hours after the second hit. PMN in the BAL and inflammatory mediator levels in the serum were measured; tissue was fixed and stained as described in the Materials and Methods section. A, PMN levels in the BAL are significantly increased in injured + LPS mice compared with LPS only. Treatment with α-C5a or C5aRa (striped bars) decreased PMN levels. Injury-primed PMN response to a second hit in C5−/− mice is shown for comparison. B, CXCL1 and IL-6 show a significant injury-primed response that is inhibited in injured mice treated with α-C5a or C5aRa before the second hit. IL-10 levels do not show an injury-primed response to LPS, consistent with IL-10 levels remaining unaffected by PC (n = 5 per group; significance *p < 0.05). C, Injured WT mice treated without or with α-C5a or C5aRa before LPS as a second hit were formalin fixed, stained, and analyzed by an experienced pathologist. Lung sections (original magnification, 20×) at 4 hours after injury are shown. Histopathology is reduced in treated mice compared with untreated mice. Specimens shown are representative of at least three animals in the treated or untreated groups.

To specifically delineate the role of C5a in PC priming, we measured inflammatory mediators in the serum and BAL of injured WT mice where C5a was neutralized with antibody after injury and before LPS challenge rather than using C5−/− mice. Our rationale was that C5−/− animals have an impaired response to initial injury and would thus be unsuitable to use to evaluate primed responses. As we previously reported,4 serum levels of CXCL1 and IL-6 mediators show an injury-primed response to LPS; IL-10 levels do not show an injury-primed response to LPS, consistent with IL-10 levels remaining unaffected by PC (Fig. 6B). We find that treating injured mice with α-C5a or C5aRa after injury decreases the primed response to LPS. Specifically, inhibition of C5a or C5aR after injury decreases IL-6, IL-10, and CXCL1 levels in the serum to levels comparable with LPS alone. We also observed decreased histopathology in the lung tissue from injured mice when C5a was neutralized before LPS challenge (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these data indicate that C5a mediates, at least in part, a primed systemic inflammatory response to a second hit after injury and uses the receptor, C5aR.

DISCUSSION

The effect of serious injury on priming the immune system for an exaggerated response to infectious challenge is often observed, poorly understood, and difficult to predict. We and others have demonstrated exaggerated TLR4-dependent responses after injury; however, the mechanisms surrounding priming after traumatic injury remain obscure. Paterson et al.,3 using a burn model of injury with LPS, suggested that priming was related to enhanced p38 activity and later suggested a role for CD4+25+ T regulatory cells in this response.2 In a rat model of intestinal ischemia-reperfusion, Fan et al.29 demonstrated enhanced CINC-1 expression by alveolar macrophages after LPS administration. Our present observations indicate a role for C5a and C5aR in the priming of the host for a second hit response to TLR4 stimulation after injury.

Emerging evidence supports functional cooperation and/or cross-regulation between the TLRs and the complement system. Zhang et al.30 demonstrated the regulation of TLR4 signaling with enhanced IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-1β in mice deficient in the membrane complement inhibitor decay-accelerating factor when challenged with LPS. These effects were primarily mediated by the C5aR and involved necrosis factor κB activation and the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) extracellular regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK).20 In models of whole human blood and a mouse model of encephalitis, Wang et al.19 suggest a regulator role for complement in TLR4-induced cytokine responses. They describe C5a as an amplifier of IL-8–dependent responses in humans and of IL-6 and KC in mice and implicate the MAPKs p38 and ERK1/2 as mediators. Furthermore, C5a enhancement of TLR-dependent responses is not restricted to TLR4 but has been described with TLR2- and TLR9-mediated responses.19,20

The mechanism(s) through which C5a stimulates TLR-mediated responses is unknown. Multiple investigators have suggested alternative explanations/pathways. Receptor colocalization between TLR2 and C5aR on lipid rafts has been described, which suggests a direct physical interaction between receptors that stabilize TLR signaling.31 Others have theorized a direct effect of C5a on TLR4, a role for CD14, and/or IL-6–induced C5aR up-regulation as possible mechanisms whereby C5a enhances TLR signaling.15,32 In addition, the contribution of C5L2, the alternative C5a receptor, has been implicated in TLR responses.33 C5L2 was originally thought to be a decoy or scavenger receptor for C5a and negatively affect C5aR signaling through competitive binding of C5a.34 However, more recent evidence indicates that C5L2 has signaling properties of its own.32 Mice deficient in C5L2 have enhanced proinflammatory cytokine responses when stimulated with LPS, and C5L2 has been shown to mediate the ability of C5a to suppress cytokine synthesis in mouse macrophages using a pathway involving phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K).35,36 In our studies, we are unable to definitively eliminate receptor colocalization or participation of C5L2 in the second-hit response after injury. Furthermore, it is possible that C5a is a messenger of the second-hit response rather than the actual priming stimulus. These possibilities and delineating the intracellular signaling pathways involved are the focus of ongoing investigations.

Classical, alternative, or lectin pathways are the typical means through which complement is activated.5 These pathways converge at C3 by forming a C5 convertase to generate the fragments, C5a, and C5b. Cross-regulation between the complement and coagulation systems has been described. Given that both systems are activated during acute inflammation and are composed of serine proteases, it is not surprising that overlap exists. Huber-Lang et al.28 demonstrated the ability of thrombin to generate C5a from C5 in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. Amara et al.27 described the ability of thrombin to cleave both C3 and C5 to generate C3a and C5a, respectively, and demonstrated similar activities with fibrin, factor Xa, and plasmin. With the use of a model of isolated traumatic lung injury, our findings in C3−/− and hirudin-treated mice confirm the presence of C5a in the absence of C3 and decreased C5a in animals treated with the thrombin-specific inhibitor, hirudin. While our findings strongly suggest that thrombin-induced C5a generation is the major pathway through which C5a is produced after blunt chest trauma, we cannot completely exclude contributions from other members of the coagulation pathway, leukocyte-derived protease activity, or serum protease activity.37,38

Prolonged systemic activation of complement after injury has been described by others. Burk et al.8 evaluated systemic levels of C5a in polytrauma patients and showed sustained C5a generation for up to 240 hours after injury. In their study, C5a levels correlated with the severity of traumatic brain injury and survival. Our human and animal data are in concordance with their findings. Furthermore, we have recently described an association between contusion volumes of greater than 24% of total lung volume and the onset of posttraumatic ARDS.21 C5a levels were significantly different between patients with greater than 24% lung contusion and less than 24% lung contusion, and further elevations in C5a levels were found in patients who subsequently developed pneumonia. Thus, our findings indicate an association between BAL C5a levels and the onset of organ dysfunction and infection after injury. It is possible that the since these samples came from polytrauma patients, our results are influenced by the magnitude of injury and degree of shock at presentation. Our intention when using BAL samples was to obtain a sample from the injured organ of interest and gain an understanding of the localized inflammatory response. It was because of these potentially confounding influences that we used an animal model of lung injury to further delineate the role of C5a in both the initial and subsequent inflammatory responses.

Our findings indicate a role for C5a in the initial innate immune response to lung contusion in a murine model of lung contusion. Others have studied the role of C5a in the initial innate immune response in animal models of traumatic lung injury. Flierl et al.13 used a blast model of lung contusion and demonstrated a role for C5a in the ensuing innate inflammatory response. When C5a was neutralized, they found reduced BAL PMN, cytokines, and chemokines with an improvement in neutrophil functional activity. We confirmed and extend their observations using C5−/− animals in our experiments where we found reduced histopathology, BAL PMN, IL-6, and CXCL1 in the C5−/− animals after lung injury. Despite differences in models and approach, taken together, clearly, there is a role for C5a in the innate inflammatory response to lung contusion.

In conclusion, our findings indicate thrombin-dependent complement activation and sustained C5a levels after lung contusion. C5a participates in the initial innate immune response to lung contusion and seems to play a role in priming for a second-hit response. Further studies are needed to address the mechanisms involved in C5a-primed injury and inflammatory responses.

Footnotes

Portions of this study were presented at the 72nd annual meeting of the American Association of Surgery for Trauma, September 18–21, 2013, in San Francisco, California.

AUTHORSHIP

J.J.H. and B.K.Y. contributed in the study design, data analysis and interpretation, as well as study reporting. J.D.W. and S.E.J. contributed in the study design, data collection, and data analysis. C.E.M. contributed in the study design and data interpretation.

References

- 1.Lasanianos NG, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. Intramedullary nailing as a ‘second hit’ phenomenon in experimental research: lessons learned and future directions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2514–2529. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy TJ, Paterson HM, Kriynovich S, et al. Linking the “two-hit” response following injury to enhanced TLR4 reactivity. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:16–23. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0704382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson HM, Murphy TJ, Purcell EJ, et al. Injury primes the innate immune system for enhanced Toll-like receptor reactivity. J Immunol. 2003;171:1473–1483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoth JJ, Martin RS, Yoza BK, Wells JD, Meredith JW, McCall CE. Pulmonary contusion primes systemic innate immunity responses. J Trauma. 2009;67:14–21. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819ea600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarma JV, Ward PA. The complement system. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo RF, Ward PA. Mediators and regulation of neutrophil accumulation in inflammatory responses in lung: insights from the IgG immune complex model. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:303–310. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecke F, Schmidt U, Kola A, Bautsch W, Klos A, Kohl J. Circulating complement proteins in multiple trauma patients—correlation with injury severity, development of sepsis, and outcome. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:2015–2024. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199712000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burk AM, Martin M, Flierl MA, et al. Early complementopathy after multiple injuries in humans. Shock. 2012;37:348–354. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182471795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fosse E, Pillgram-Larsen J, Svennevig JL, et al. Complement activation in injured patients occurs immediately and is dependent on the severity of the trauma. Injury. 1998;29:509–514. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busche MN, Stahl GL. Role of the complement components C5 and C3a in a mouse model of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Ger Med Sci. 2010;8 doi: 10.3205/000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai C, Gill R, Eum HA, et al. Complement factor 3 deficiency attenuates hemorrhagic shock-related hepatic injury and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R1175–R1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00282.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu DZ, Zaets SB, Chen R, et al. Elimination of C5aR prevents intestinal mucosal damage and attenuates neutrophil infiltration in local and remote organs. Shock. 2009;31:493–499. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318188b3cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flierl MA, Perl M, Rittirsch D, et al. The role of C5a in the innate immune response after experimental blunt chest trauma. Shock. 2008;29:25–31. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180556a0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shushakova N, Skokowa J, Schulman J, et al. C5a anaphylatoxin is a major regulator of activating versus inhibitory FcgammaRs in immune complex-induced lung disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1823–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajishengallis G, Lambris JD. Crosstalk pathways between Toll-like receptors and the complement system. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang C, Zhang X, Miwa T, Song WC. Complement promotes the development of inflammatory T-helper 17 cells through synergistic interaction with Toll-like receptor signaling and interleukin-6 production. Blood. 2009;114:1005–1015. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Neff TA, et al. Increased C5a receptor expression in sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:101–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI15409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaeffer V, Cuschieri J, Garcia I, et al. The priming effect of C5a on monocytes is predominantly mediated by the p38 MAPK pathway. Shock. 2007;27:623–630. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31802fa0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Han G, Wang R, et al. Regulation of IL-8 production by complement-activated product, C5a, in vitro and in vivo during sepsis. Clin Immunol. 2010;137:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Lewkowich IP, Kohl G, Clark JR, Wills-Karp M, Kohl J. A protective role for C5a in the development of allergic asthma associated with altered levels of B7-H1 and B7-DC on plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5123–5130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becher RD, Colonna AL, Enniss TM, et al. An innovative approach to predict the development of adult respiratory distress syndrome in patients with blunt trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1229–1235. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825b2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoth JJ, Hudson WP, Brownlee NA, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 participates in the response to lung injury in a murine model of pulmonary contusion. Shock. 2007;28:447–452. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318048801a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoth JJ, Wells JD, Brownlee NA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 dependent responses to lung injury in a murine model of pulmonary contusion. Shock. 2008;31:376–381. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181862279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoth JJ, Wells JD, Yoza BK, McCall CE. Innate immune response to pulmonary contusion: identification of cell-type specific inflammatory responses. Shock. 2012;37:385–391. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182478478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perl M, Gebhard F, Bruckner UB, et al. Pulmonary contusion causes impairment of macrophage and lymphocyte immune functions and increases mortality associated with a subsequent septic challenge. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1351–1358. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000166352.28018.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amara U, Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, et al. Molecular intercommunication between the complement and coagulation systems. J Immunol. 2010;185:5628–5636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, et al. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nm1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan J, Marshall JC, Jimenez M, Shek PN, Zagorski J, Rotstein OD. Hemorrhagic shock primes for increased expression of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant in the lung: role in pulmonary inflammation following lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1998;161:440–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Kimura Y, Fang C, et al. Regulation of Toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory response by complement in vivo. Blood. 2007;110:228–236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang M, Krauss JL, Domon H, et al. Microbial hijacking of complement-toll-like receptor crosstalk. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Nadeau BA, et al. Functional roles for C5a receptors in sepsis. Nat Med. 2008;14:551–557. doi: 10.1038/nm1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao H, Neff TA, Guo RF, et al. Evidence for a functional role of the second C5a receptor C5L2. FASEB J. 2005;19:1003–1005. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3424fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scola AM, Johswich KO, Morgan BP, Klos A, Monk PN. The human complement fragment receptor, C5L2, is a recycling decoy receptor. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1149–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raby AC, Holst B, Davies J, et al. TLR activation enhances C5a-induced pro-inflammatory responses by negatively modulating the second C5a receptor, C5L2. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2741–2752. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wrann CD, Tabriz NA, Barkhausen T, et al. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway exerts protective effects during sepsis by controlling C5a-mediated activation of innate immune functions. J Immunol. 2007;178:5940–5948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber-Lang M, Younkin EM, Sarma JV, et al. Generation of C5a by phagocytic cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1849–1859. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64461-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huber-Lang M, Denk S, Fulda S, et al. Cathepsin D is released after severe tissue trauma in vivo and is capable of generating C5a in vitro. Mol Immunol. 2012;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]