Abstract

Background

Population-based surveys (self-report) and health insurance administrative data (HEDIS) are used to estimate chlamydia screening coverage in the U.S. Estimates from these methods differ, but few studies have compared these two indices in the same population.

Methods

In 2010, we surveyed a random sample of women aged 18–25 enrolled in a Washington State managed care organization. Respondents were asked if they were sexually active in last year and if they tested for chlamydia in that time. We linked survey responses to administrative records of chlamydia testing and reproductive/testing services used, which comprise the HEDIS definition of the screened population and the sexually active population, respectively. We compared self-report and HEDIS using three outcomes: (1) sexual activity (gold-standard=self-report); (2) any chlamydia screening (no gold standard); and (3) within-plan chlamydia screening (gold-standard=HEDIS).

Results

Of 954 eligible respondents, 377 (40%) completed the survey and consented to administrative record linkage. Chlamydia screening estimates for HEDIS and self-report were 47% and 53%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of HEDIS to define sexually active women were 84.8% (95% CI=79.6%–89.1%) and 63.5% (95% CI=52.4%–73.7%), respectively. Forty percent of women had a chlamydia test in their administrative record but 53% self-reported being tested for chlamydia (kappa=0.35); 19% reported out-of-plan chlamydia testing. The sensitivity of self-reported within-plan chlamydia testing was 71.3% (95% CI=61.0%–80.1%); the specificity was 80.6% (95% CI=72.6%–87.2%).

Conclusions

HEDIS does not accurately identify sexually active women and may underestimate chlamydia testing coverage. Self-reported testing may not be an accurate measure of true chlamydial testing coverage.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis infection is the most commonly reported infection in the United States (US).1 Screening asymptomatic young women is the cornerstone of US national efforts to control chlamydial infection; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Preventative Services Task Force, and numerous professional medical associations recommend annual chlamydia screening for all sexually active women in the US aged <26 years.2–5 However, while national chlamydia screening recommendations were developed and released two decades ago,6,7 efforts to monitor the uptake of the testing recommendations have been problematic. Owing to inconsistencies in defining the sexually active population (denominator) and identifying the number of women who are tested annually (numerator), published estimates of the proportion of sexually active women aged <26 years tested for C. trachomatis annually vary widely.8–13

The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure of chlamydial testing is one of the most widely used and cited methods for estimating chlamydia testing coverage. The HEDIS measure uses insurance claims and administrative data from women enrolled in commercial or Medicaid health plans to determine the number of sexually active women who are tested each year. Although the HEDIS measure is a performance measure to assess quality of care in managed care organizations, public health officials have used it as a proxy for population-level screening coverage.7 However, when used to assess testing coverage, HEDIS is limited in a number of ways. First, the use of claims data to define the sexually active population may misestimate the number of women who are truly sexually active and require screening.14 Second, the HEDIS measure applies only to insured women and is further limited to women who receive care in a given year. Finally, the measure does not consistently identify testing that occurs out-of-plan. To address these limitations, CDC investigators have used self-reported data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) as an alternative approach to calculate testing coverage.8 While self-reported data likely provide the best possible estimates of sexual activity, the validity of self-reported chlamydia testing has not been well-studied. Thus, the usefulness of population-based surveys to estimate screening coverage is unknown.

In the current study, we compared self-reported and HEDIS estimates of chlamydia screening among female enrollees of a managed care health plan. Our goals were to: (1) determine the validity of the HEDIS measure to define sexually active women; (2) evaluate the agreement between HEDIS and self-reported estimates of chlamydia testing; and (3) determine the validity of self-reported chlamydia testing among women tested within plan.

METHODS

Study population, design, and data collection

This study was conducted among enrollees of Group Health Cooperative (GH), a mixed-model managed care system in Washington State. Eligible study participants were women aged 18–25 years who were continuously enrolled in GH in 2009 (i.e., <1 month break in service in the entire calendar year). We excluded women <18 years of age because parental consent would be required to participate. The survey was administered in July 2010.

We selected a stratified (by age: 18–21 versus 22–25; and residence: Eastern versus Western Washington) random sample of 1,000 eligible enrollees, to whom we mailed a self-administered questionnaire. A pre-incentive of $2.00 was included in the initial mailing and women who returned the questionnaire were sent an additional $10.00.

The self-administered 2-page questionnaire, which referenced activities or services used in 2009, queried women on their demographics (e.g., race, marital status, education), sexual activity (e.g., vaginal sex and number of sex partners), and health care utilization (e.g., tested for chlamydia, had a pelvic exam). Responses from the questionnaire were used to define self-reported sexual activity and chlamydia testing. As part of the survey, we requested permission to link respondents’ questionnaire responses to their GH electronic medical records. Data from these same databases are the source of GH HEDIS data, and were used to construct the HEDIS measure of sexual activity and chlamydia testing.

The final study population includes women who returned the questionnaire by September 2010 and who consented to have their survey data linked to their automated medical data. Table 1 summarizes the strategies used to evaluate the three analytic aims, described below.

Table 1.

Definitions of Population, Gold Standard and Comparison Methods for Each of Three Aims

| Aim | Gold Standard | Comparison Method | Population Included in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validity of HEDIS to define the sexually active population | Self-report: Reported vaginal sex with a man in 2009 | HEDIS: ICD, CPT, NDC, and HCPCS claim codes or visits for pregnancy, contraception, STD diagnosis, screening or treatment, or cervical cancer screening in 2009 administrative medical record | Women whose administrative medical record indicated they had ≥1 GH visit in 2009 |

| Agreement between HEDIS and self-reported chlamydia testing | None | Self-report: Reported being tested for chlamydia either within plan or outside plan in 2009 HEDIS: ≥1 recorded chlamydia test in 2009 administrative medical record |

Women who self-reported being sexually active in 2009 |

| Validity of self-reported chlamydia testing | HEDIS: ≥1 recorded chlamydia test in 2009 administrative record | Self-report: Reported being tested for chlamydia within GH in 2009 | Women who self-report being sexually active in 2009 and did not report being tested for chlamydia outside GH in 2009 |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedure Terminology; HEDIS, Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NDC, National Drug Code; STD, sexually transmitted disease

Validity of HEDIS to define sexually active women

To estimate the validity of the HEDIS definition of the sexually active population, we assumed self-reported sexual activity was the gold standard. Women defined as sexually active per self-report were those who answered in the affirmative to the following question: “In 2009, did you have vaginal sex with a man? For this survey, vaginal sex means that a man put his penis in your vagina”. Following the HEDIS definition of sexual activity,15 we classified women as sexually active per HEDIS if they had diagnosis, prescription or lab codes (International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), National Drug Code (NDC), or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes) from 2009 that identified services related to a Pap test or pelvic exam, a contraceptive service, a pregnancy-related service, or screening or treatment for a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

We calculated the sensitivity (numerator = number of women classified as sexually active by HEDIS; denominator = number of women classified as sexually active by self-report) and specificity (numerator = number of women classified as not sexually active by HEDIS; denominator = number of women classified as not sexually active by self-report) of the HEDIS definition, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We stratified this analysis by 2-year age groups because we hypothesized that the validity of HEDIS may depend on the respondent’s age.14 Because the HEDIS measure of sexual activity only includes women who used health care services, this analysis excluded women whose administrative record indicated they had no utilization or claims submitted to GH in 2009.

Agreement of self-report and HEDIS estimates of chlamydia testing

Among women who self-reported being sexually active, we evaluated the agreement between self-reported chlamydia testing and the HEDIS measure of chlamydia testing. We limited this analysis to self-reported sexually active women instead of HEDIS-defined sexually active women because of the perceived superior validity of self-report.

Women who had at least one chlamydia test in their 2009 GH medical record were classified as having been tested per HEDIS. Women who did not have a chlamydia test in their record or who were not defined as sexually active per HEDIS were classified as non-tested per HEDIS. Self-reported chlamydia testing information was obtained from the following survey question: “In 2009, were you tested by a doctor or other medical person for chlamydia? Chlamydia is a common sexually transmitted disease. Doctors sometimes test for it when they do a pelvic exam or when they take urine”. For this question, women could indicate if they had been: (1) tested within GH; (2) tested outside of GH; (3) tested within GH and outside GH; or (4) not tested. We calculated the agreement between these two measures using the kappa statistic with 95% CI.

Validity of self-reported chlamydia testing within GH

Among women who self-reported being sexually active and who did not indicate that they were tested for chlamydia exclusively outside GH, we used the HEDIS measure of chlamydia testing as the gold-standard to estimate the validity of self-reported testing. We considered HEDIS to be the gold-standard since any women who received chlamydia testing within GH should have a test included as part of their health plan administrative data. Self-reported chlamydia testing and the HEDIS measure of chlamydia testing for this aim followed the same definition as described above for the agreement analysis.

We estimated the sensitivity (numerator = number of sexually active women who self-reported being tested for chlamydia within GH; denominator = number of sexually active women tested per HEDIS) and specificity (numerator = number of sexually active women who self-reported not being tested for chlamydia; denominator = number of sexually active women not tested per HEDIS) of self-reported chlamydia testing with 95% CI.

In an ancillary validity analysis, we estimated the sensitivity and specificity of self-reported chlamydia positivity, using the medical record test result as the gold-standard. This analysis was limited to self-reported sexually active women with a chlamydia test in their record.

All analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Study procedures were approved by the GH Human Subjects Review Committee.

RESULTS

Of our initial sample of 1,000 eligible enrollees, 46 were sampled erroneously or had incorrect addresses on file. Of the remaining 954 women, 465 (48.7%) returned the questionnaire and 377 (81.1%) of 465 agreed to have their questionnaire responses linked to their medical record. Characteristics of women who did (n=377) and did not (n=88) agree to medical record linkage did not significantly differ with one exception: women who agreed to linkage were more likely to self-report testing for chlamydia in 2009 compared to women who did not (41.1% versus 29.4%, respectively; P=0.05).

Forty-seven percent of respondents were 18–21 years old, approximately three-quarters were White non-Hispanic, and most (n=269, 71%) reported having vaginal sex in 2009 (Table 2). Using only self-reported data, 142 (52.8%) of the 269 women who reported being sexually active were tested for chlamydia in 2009. Using the HEDIS definitions of testing and sexual activity, 113 (47.3%) of 239 sexually active women were tested.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Population in 2009 (N = 377)

| Self-reported characteristics, from study questionnaire | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 18–19 | 88 | 23.3 |

| 20–21 | 88 | 23.3 |

| 22–23 | 101 | 26.8 |

| 24–25 | 100 | 26.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 286 | 76.1 |

| Black | 5 | 1.3 |

| Asian | 24 | 6.4 |

| Hispanic | 33 | 8.8 |

| Other | 28 | 7.5 |

| Lived outside Washington state | 58 | 15.4 |

| Student status | ||

| High school | 24 | 6.4 |

| College or graduate school | 171 | 45.4 |

| Both high school and college | 36 | 9.6 |

| Other school type | 11 | 2.9 |

| Not a student | 135 | 35.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 279 | 74.0 |

| Married | 59 | 15.7 |

| Living with partner but unmarried | 39 | 10.3 |

| Sexually active (vaginal sex) | 269 | 71.4 |

| Sexually active (vaginal sex) by agea | ||

| 18–19 (n = 88) | 52 | 59.1 |

| 20–21 (n = 88) | 54 | 61.4 |

| 22–23 (n = 101) | 84 | 83.2 |

| 24–25 (n = 100) | 81 | 81.1 |

| Tested for chlamydia, among sexually active women (N=269)b | ||

| Yes, within GH | 91 | 33.8 |

| Yes, outside GH only | 51 | 19.0 |

| Not tested | 127 | 47.2 |

| Had chlamydia in 2009 | 9 | 2.4 |

| Ever had chlamydia | 29 | 7.7 |

|

| ||

| Characteristics from administrative record | ||

|

| ||

| ≥1 visit/claim to GH | 322 | 85.4 |

| Sexually active (HEDIS definition) | 239 | 63.4 |

| ≥1 chlamydia test billed to GH | 113 | 30.0 |

| ≥1 positive chlamydia test | 5 | 4.4 |

Abbreviations: GH, Group Health; HEDIS, Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set

Proportions represent row percentages

Denominator for proportions is the number of self-reported sexually active women (N=269)

Validity of HEDIS to define sexually active women

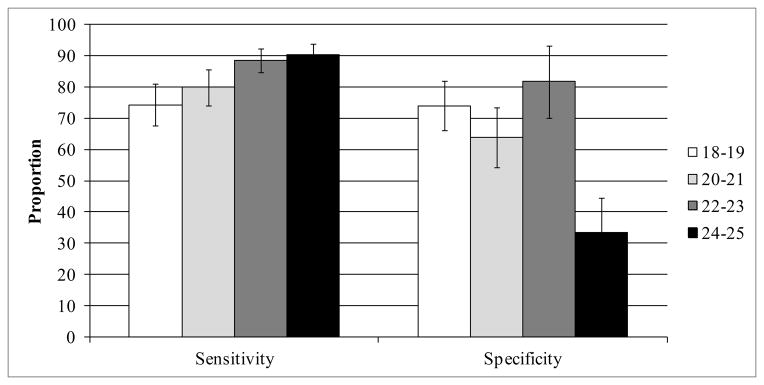

Of 322 women who had at least one contact with GH recorded in the administrative data, 237 (73.6%) self-reported being sexually active. Of these, 201 were classified as sexually active by HEDIS (sensitivity = 84.8%; 95% CI: 79.6% – 89.1%). Of 85 women who reported not being sexually active, 54 were classified as non-sexually active per HEDIS (specificity = 63.5%; 95% CI: 52.4% – 73.7%). As age increased, the sensitivity of HEDIS to define sexually active women increased, while the specificity generally decreased, with one exception (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Sensitivity and Specificity of HEDIS to Define Sexually Active Women using Self-report as the Gold-standard, Stratified by Agea.

Abbreviations: HEDIS, Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set

aError bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Stratum-specific sample sizes: 18–19: n=74; 20–21: n=75; 22–23: n=82; 24–25: n=91

Agreement of self-report and HEDIS estimates of chlamydia testing

Among self-reported sexually active respondents (n=269), 108 (40.1%) had a chlamydia test in their administrative record but 142 (52.8%) self-reported being tested for chlamydia (kappa = 0.35) (Table 3). Approximately 19% (51 of 269) indicated that they were tested exclusively outside of GH. Only 14 (27%) of these 51 women had a chlamydia test in their record (Table 3) and 13 (25%) were classified as not sexually active per HEDIS (data not shown).

Table 3.

Agreement and Validity of Self-reported Versus HEDIS Measures of Chlamydia Testing

| Self-reported measure | HEDIS measure

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested | Not Tested | Total | ||

| Agreement | Reported testing for chlamydia | N = 108 | N = 161 | N = 269 |

|

| ||||

| Yes, tested inside or outside GH | 81 | 61 | 142 | |

| Yes, tested outside GH onlya | 14 | 37 | 51 | |

| Not tested | 27 | 100 | 127 | |

| Agreement (%) and 95% CI | 67.3 | 61.3 – 72.9 | ||

| Kappa and 95% CI | 0.35 | 0.25 – 0.46 | ||

|

| ||||

| Validity | Reported testing for chlamydia within GH | N = 94 | N = 124 | N = 218 |

|

| ||||

| Yes, tested within GH | 67 | 24 | 91 | |

| Not tested | 27 | 100 | 127 | |

| Sensitivity (%) and 95% CI | 71.3 | 61.0 – 80.1 | ||

| Specificity (%) and 95% CI | 80.6 | 72.6 – 87.2 | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HEDIS, Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set; GH, Group Health

Represents women who received out-of-plan care

Validity of self-reported chlamydia testing within GH

Among women who self-reported being sexually active (n=269), 218 did not report testing for chlamydia exclusively outside GH; these women were included in this analysis. Sixty-seven of the 94 women classified as tested using HEDIS criteria self-reported that they were tested at GH in the prior year (sensitivity of self-report = 71.3%; Table 3); 100 of 124 women who were not tested per HEDIS criteria reported that they were not tested in 2009 (specificity of self-report = 80.6%). Among women who reported being tested at GH, 26.4% (24 of 91) did not have a chlamydia test in their administrative medical record (Table 3).

Of 108 women with a chlamydia test in their GH record, five (4.6%) had a positive test. All five women self-reported testing positive (sensitivity = 100.0%). Of 103 women with a negative chlamydia test in their record, 101 self-reported testing negative (specificity = 98.1%; 95% CI: 93.2% – 99.8%).

DISCUSSION

In a population of young, female health plan enrollees, we found that the HEDIS measure and patient self-report yielded similar overall estimates of the percentage of women tested for C. trachomatis (47% versus 53%); however, the agreement between HEDIS and self-report was suboptimal. HEDIS somewhat overestimated the percentage of the population that was sexually active, and a substantial number of women – 36% who self-reported testing for chlamydia – reported testing outside of their health plan, suggesting that the HEDIS measure may be insensitive. At the same time, the sensitivity of self-report was relatively low and only moderately specific in identifying women who were tested for chlamydia within their health plan. Overall, our findings indicate that, for different reasons, neither the HEDIS measure nor self-report are likely to be accurate measures of chlamydial screening, and suggest the need for new approaches to estimate population-level chlamydia screening coverage.

The HEDIS estimate of chlamydia testing in this population is similar to national HEDIS estimates from 2009 (47.3% versus 43.1%, respectively)13 but our self-reported estimate is higher than that obtained from the 2006–2008 NSFG (52.8% versus 37.9%, respectively).8 We suspect the discrepancy in estimates between the current study and that of NSFG reflects differences between the two populations with respect to age (i.e., women aged 18–25 versus women aged 15–25, respectively) or insurance coverage (i.e., enrollees in a managed care health plan versus the general population of sexually active women, respectively).

Despite the similarity of HEDIS and self-reported estimates of testing coverage in our population, the agreement between these two methods of estimation was only fair,16 as nearly one-third of women were discordantly classified (i.e., classified as tested by one method of estimation but not the other). This is partially explained by the fact that we limited the agreement analysis to self-reported sexually active women, which lowered the HEDIS-defined screening estimate. Nonetheless, these data suggest that HEDIS and self-report capture different women in their respective screening estimates, and that the potential for discrepancies between the two methods may be substantial.

Our findings highlight two important limitations of the HEDIS measure of chlamydia screening. First, these data indicate that HEDIS overestimates the number of women who are sexually active, which could lead to an underestimation of the proportion of women screened. Among our study population, nearly 40% of those who denied any sexual activity were classified as sexually active based on HEDIS administrative data (specificity = 63%), and this low specificity was especially pronounced among women aged 24–25. These relatively older women may utilize reproductive health care services but may not currently be sexually active; thus, their inclusion in the denominator could falsely lower screening estimates in that population. Second, we found that approximately one-fifth of our sexually active respondents reported testing for chlamydia exclusively out-of-plan. Only a portion of these women had a test in their record and one-quarter were excluded from the HEDIS estimate completely. The former misclassification would result in an underestimation of screening, since these women would be included in the denominator (they accessed reproductive health services at GH) but not the numerator (their out-of-plan test did not result in a claim). In contrast, women who did not access any reproductive health services at GH and who were tested for chlamydia outside GH would be excluded from both the numerator and denominator of the HEDIS screening estimate. The effect of this exclusion could increase or decrease the screening estimate depending on the level of screening among these women. However, a previous study of the same managed care population found that adolescents who use out-of-plan care were at higher risk for STIs;17 thus, better strategies for monitoring screening trends in this population are needed.

We were hopeful that the self-reported estimates of chlamydia testing would prove valid. However, nearly 30% of women who had a test in their GH record reported that they had not been tested, indicating that self-report is not a highly accurate approach for estimating population-level screening coverage. Further, 26% of women who reported being tested at GH had no evidence of a test in their record. This finding is particularly important for health care providers who rely on patient self-report to assess chlamydia testing history.

There are a number of possible explanations for the low sensitivity of self-reported screening that we observed. First, these women may have been unaware of having been tested, as previous research suggests that knowledge of chlamydia testing procedures is low.18–23 Second, it is possible that respondents did not accurately recall the timing of their chlamydia test (we sent questionnaires in mid-2010 and asked respondents to recall their health care utilization in 2009). Third, some women who reported being tested for chlamydia within GH may have actually been tested out-of-plan; these tests may or may not be captured by the HEDIS estimate.

This study has a number of strengths. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to directly compare self-reported and HEDIS measures of chlamydia testing within the same patient population. This allowed us to directly quantify the discrepancies of the two methods. We obtained data from the administrative databases of a large managed care organization to obtain HEDIS estimates, and our eligible study population was a random sample of enrollees.

There are also a number of limitations. First, less than one-half of eligible respondents completed the self-administered questionnaire. These non-responders may have different health care utilization or chlamydia testing patterns than our study population. Further, 20% of women who returned the questionnaire did not agree to have their questionnaire linked to their medical record, and a smaller percentage of these women self-reported testing for chlamydia compared to women included in the study. Second, as noted above, self-reported sexual activity and testing are subject to recall bias. Third, the question about chlamydia testing may have led some women to believe that a routine pelvic exam includes testing for chlamydia, which could have increased the proportion of women who inaccurately reported being tested. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other populations. Our study population included only those women enrolled in a managed care organization and excluded women who were <18 years of age.

In summary, our findings suggest that neither the HEDIS measure nor self-report yield accurate estimates of chlamydia testing coverage. The results from this study underscore the need to develop a standardized method to estimate population-level screening coverage. New methods to estimate coverage, including indirect estimation from surveillance data11 and laboratory data,12 have been developed and hold promise, but they are sensitive to variations in estimates of chlamydia positivity and the source of laboratory positivity data, respectively. With the movement toward a universally insured population and the emergence of data sharing across electronic medical record systems, estimates of chlamydia testing will likely become more accurate. However, given the additional complexity of defining the sexually active population, the most appropriate method to estimate screening coverage almost certainly involves combining data sources to separately estimate the components of the screening coverage estimate. By doing this, a standardized, population-based testing coverage estimate could be implemented to provide the best possible estimates of chlamydia screening coverage in the US.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chlamydia Evaluation Initiative and the National Institutes of Health [grant T32 AI07140 to C.M.K].

The authors thank the study participants and Group Health Research Institute staff.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

M.R.G. has received research support from Cempra Pharmaceuticals, and Melinta Pharmaceuticals for his work outside this study. All other authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2012. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyers DS, Halvorson H, Luckhaupt S, et al. Screening for chlamydial infection: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:135–42. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Congress on Obstetricians and Gynecologists. [Accessed December 3, 2013];Chlamydia and Gonorrhea Screening a Must for Women 25 and Younger. 2013 Available at: http://acogpresident.org/2013/04/11/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening-a-must-for-women-25-and-younger/

- 5.Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics. [Accessed December 4, 2013];Recommendations for Preventative Pediatric Health Care. 2008 Available at: http://brightfutures.aap.org/pdfs/AAP_Bright_Futures_Periodicity_Sched_101107.pdf.

- 6.1993 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;42:1–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease C and Prevention. CDC Grand Rounds: Chlamydia prevention: challenges and strategies for reducing disease burden and sequelae. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2011;60:370–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao G, Hoover KW, Leichliter JS, et al. Self-reported Chlamydia testing rates of sexually active women aged 15–25 years in the United States, 2006–2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:605–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318254c837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao G, Hoover KW, Kent CK. Chlamydia testing patterns for commercially insured women, 2008. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;42:337–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heijne JC, Tao G, Kent CK, et al. Uptake of regular chlamydia testing by U.S. women: a longitudinal study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010;39:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine WC, Dicker LW, Devine O, et al. Indirect estimation of Chlamydia screening coverage using public health surveillance data. American journal of epidemiology. 2004;160:91–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broad JM, Manhart LE, Kerani RP, et al. Chlamydia screening coverage estimates derived using healthcare effectiveness data and information system procedures and indirect estimation vary substantially. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:292–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182809776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Accessed December 3, 2013];The State of Health Care Quality 2012. 2012 Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/State%20of%20Health%20Care/2012/SOHC%20Report%20Web.pdf.

- 14.Tao G, Walsh CM, Anderson LA, et al. Understanding sexual activity defined in the HEDIS measure of screening young women for Chlamydia trachomatis. The Joint Commission journal on quality improvement. 2002;28:435–40. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2008: technical specifications. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Civic D, Scholes D, Grothaus L, et al. Adolescent HMO enrollees’ utilization of out-of-plan services. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2001;28:491–6. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Head SK, Crosby RA, Shrier LA, et al. Young women’s misperceptions about sexually transmissible infection testing: a ‘clean and clear’ misunderstanding. Sexual health. 2007;4:273–5. doi: 10.1071/sh07060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman K, Black CM, Persaud P, et al. Patient Knowledge of Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Testing in An Urban Clinic: A Comparison of Patient Perceived Testing and Actual Tests Performed. 2012 National STD Prevention Conference; Minneapolis, MN. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Head SK, Crosby RA, Moore GR. Pap smear knowledge among young women following the introduction of the HPV vaccine. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2009;22:251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogbechie OA, Hacker MR, Dodge LE, et al. Confusion regarding cervical cancer screening and chlamydia screening among sexually active young women. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:35–7. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breitkopf CR, Pearson HC, Breitkopf DM. Poor knowledge regarding the Pap test among low-income women undergoing routine screening. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2005;37:78–84. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.078.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royer HR, Falk EC, Heidrich SM. Sexually transmitted disease testing misconceptions threaten the validity of self-reported testing history. Public health nursing. 2013;30:117–27. doi: 10.1111/phn.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]