Abstract

The −13910C>T polymorphism (rs4988235) upstream from the lactase (LCT) gene, strongly associated with lactase persistence (LP) in Europeans, is emerging as a new candidate for obesity. We aimed to analyze the association of this polymorphism with obesity-related variables and its modulation by dairy product intake in an elderly population. We studied 940 high-cardiovascular risk Spanish subjects (aged 67 ± 7 years). Dairy product consumption was assessed by a validated questionnaire. Anthropometric variables were directly measured, and metabolic syndrome-related variables were obtained. Prevalence of genotypes was: 38.0% CC (lactase nonpersistent (LNP)), 45.7% CT, and 16.3% TT. The CC genotype was not associated with lower milk or dairy product consumption in the whole population. Only in women was dairy intake significantly lower in CC subjects. The most important association was obtained with anthropometric measurements. CC individuals had lower weight (P = 0.032), lower BMI (29.7 ± 4.2 vs. 30.6 ± 4.2 kg/m2; P = 0.003) and lower waist circumference (101.1 ± 11.8 vs. 103.5 ± 11.5 cm; P = 0.005) than T-allele carriers. Obesity risk was also significantly higher in T-allele carriers than in CC individuals (odds ratio (OR): 1.38; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.05–1.81; P = 0.01), and remained significant even after adjustment for sex, age, diabetes, physical activity, and energy intake. However, in subgroup analysis, these associations were found to be significant only among those consuming moderate or high lactose intakes (>8 g/day). No significant associations with lipids, glucose, or blood pressure were obtained after adjustment for BMI. In conclusion, despite not finding marked differences in dairy product consumption, this polymorphism was strongly associated with BMI and obesity and modulated by lactose intake in this Mediterranean population.

INTRODUCTION

The association of dairy food consumption with obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors has been investigated in several studies, but with contradictory results (1–6). A beneficial effect of dairy consumption on the incidence of various metabolic syndrome components (including obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) was reported by Pereira et al. (1) in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study and replicated in some (2–4), but not all (5,6) subsequent studies. Some meta-analyses carried out for this purpose reflect the inconsistency of results and underline the need to analyze the different factors involved in greater depth (7–9). One of the potential factors that may affect the quantity of milk consumed as well as the effects of dairy products on obesity and obesity-related variables in adults is lactose intolerance or lactase nonpersistence (LNP). Lactose intolerance is the syndrome of diarrhea, abdominal pain, or flatulence, occurring after lactose ingestion (10). These symptoms, caused by a decreased ability to hydrolyze lactose due to the decrease in the lactase expression, may have an influence in the amount of dairy product consumed. On the other hand, if there is no restriction of dairy products in LNP subjects, the undigested lactose may have several metabolic effects that may be related to obesity.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Lactase is coded by the lactase gene (LCT), and LCT activity remains high until weaning, then it fades away in most of the adult population (adult-type hypolactasia or LNP). A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs4988235), located at −13,910 bp upstream from the LCT gene (−13910C>T) within intron 13 of the adjacent minichromosome maintenance 6 (MCM6) gene was found to be associated with lactase persistence (LP) (11). Various studies (11–13) have demonstrated that the −13910C>T SNP is functional and is associated with changes in LCT gene expression. Individuals homozygous for the C allele (LNP) have almost undetectable levels of intestinal lactase production compared to TC or TT individuals (LP), following a codominant model (11). Pohl et al. (14) found an excellent agreement between the lactose hydrogen test (10) and the genetic test based on this SNP for LNP in Europeans. The frequency of LP is high in northern European populations, decreases across southern Europe and more than half of the world’s population is LNP (15). Although some studies have associated the CC genotype with a lower consumption of milk (16–18), this association is not always observed (19–21).

Interestingly, the LCT gene is emerging as a new candidate gene related with obesity and other anthropometric measurements. Hence, in a recent Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAs) carried out by Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology (CHARGE), the Consortium (22) found a strong association between various SNPs in the LCT gene and waist circumference. Likewise, Kettunen et al. (23), undertook a meta-analysis on eight European cohorts (in which the Mediterranean population was not included) finding a strong association between the LP variant (T allele, rs4988235) and higher BMI. However, none of the published studies has analyzed the joint influence of the LP genotype and dairy product consumption on obesity. Therefore, our aim was to study the association of the LCT −13910C>T polymorphism with obesity and obesity-related variables as well as its modulation by lactose intake in an elderly Mediterranean population.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Subjects and study design

We studied 940 unrelated ethnically homogeneous individuals (338 men and 602 women), mean age 67.3 ± 6.5 years, who participated in the PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) study. All of them were consecutively recruited in the Valencia Region (on the East Mediterranean coast of Spain) from October 2003 to December 2008 and had the −13910C>T SNP genotype determined. The ethics committee of the University of Valencia approved the study and all participants gave their informed consent. Details of this study have been previously reported (24). Briefly, high-cardiovascular risk subjects were selected by physicians in Primary Care Centers participating in the study. Eligible subjects were community-dwelling people (55–80 years of age for men; 60–80 years of age for women) who fulfilled at least one of two criteria: type 2 diabetes; three or more cardiovascular risk factors (current smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, overweight, or a family history of premature cardiovascular disease).

Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical measurements

The baseline examination included assessment of standard sociodemographic factors, clinical, biochemical, and lifestyle variables, as previously detailed (24). Anthropometric variables were directly measured by trained nurses by standard techniques at baseline (24). Height and weight were measured with light clothing and no shoes. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest using an anthropometric tape. Trained personnel measured blood pressure with a validated semiautomatic sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM-705CP; Omron, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands) in a seated position after a 5-min rest. Physical activity was estimated by the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity as previously reported (24). Blood samples were obtained for each participant after an overnight fast and were frozen at −80 °C. Fasting glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol were determined as previously reported (24). The metabolic syndrome was defined according to updated ATP III criteria (25), which require that three or more of the following conditions be met: abdominal obesity (waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women), hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides level 150 mg/dl), low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol level (<40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women), elevated fasting blood glucose level (100 mg/dl), and elevated blood pressure (systolic 130 mm Hg, diastolic 85 mm Hg, or taking antihypertensive medication). Participants who were being treated with antidiabetic, antihypertensive, or triglyceride-lowering medications were considered to be diabetic, hypertensive, or hypertriglyceridemic, respectively.

Dietary measurements

Food consumption was determined by a validated (26) semiquantitative 137-item food frequency questionnaire. Energy and nutrient intake were calculated from Spanish food composition tables (27). Lactose content was not available in the Spanish tables and so foreign food composition tables were used (Fineli Food Composition Database, Finland, release 2010). The questionnaire was based on the typical portion sizes that were multiplied by the consumption frequency for each food. Information about dairy products was assessed in fifteen items of the semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (whole-fat milk, partially skimmed milk, skimmed milk, condensed milk, whipped cream, yoghurt, skimmed yoghurt, milkshake, ricotta cheese or curd, petit Suisse cheese, spreadable cheese wedges, cottage cheese, other cheese, custard, and ice cream). We calculated total dairy products intake (in g/day) for each individual on the basis of the type and amount consumed.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood. The LCT −13910C>T (rs4988235) polymorphism was determined using a 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and a customized fluorescent allelic discrimination TaqMan assay by standard procedures. For quality control purposes, 50% of randomly selected samples were also genotyped by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Concordance between techniques was >95%. Discrepant samples were sequenced. Information on probes and PCR conditions for genotyped SNPs can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Statistical analysis

χ2-tests were used to test differences in percentages. Taking into account that the genetically defined LP is considered to follow a dominant model, CT and TT subjects (LP) were grouped and compared with CC subjects for the statistical analysis after having checked that this dominant model is observed in this Mediterranean population. We applied the t-tests to compare crude means for normally distributed variables. Alcohol and dairy product consumption did not follow a normal distribution and we applied the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test. For continuous anthropometric variables, multivariate adjustment was carried out by linear regression analysis. Model were adjusted for sex, age (as continuous), diabetes, total energy intake (as continuous), and physical activity (as continuous). Additional adjustments for dairy product consumption or medications (antihypertensives, lipid-lowering drugs, and diabetes treatment) were also done. Multivariate adjustment of plasma lipids, fasting glucose, and blood pressure was also carried out by linear regression. Regression coefficients and adjusted means for each predictor were estimated from the multivariate models. Regression models with interaction terms and as well as stratified analysis were applied to test the homogeneity of effects by gender and lactose intake. Logistic regression models were fitted to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of obesity and obesity-related variables associated with the LP genotype compared with LNP. Analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows general characteristics of the study subjects by gender. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome was high given that this study involved a population that was selected for being elderly and with a high-cardiovascular risk. Total dairy product consumption was higher in women than in men (395 ± 230 g/day vs. 322 ± 194 g/day, respectively; P < 0.001). Men consumed a greater amount of whole-fat milk whereas women consumed more skimmed milk and skimmed yoghurt, and there were no significant differences between men and women in the amount of whole-fat yoghurt consumed. Likewise, total cheese intake did not differ between men and women. The amount of lactose intake derived from dairy products was also significantly higher in women than men (P = 0.01). However, there were no significant differences in the percentage of men and women who claim never to consume milk (14.2% vs. 14%; P = 0.994).

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric, dietary, and genetic characteristics of the studied subjects

| Men (n = 338) | Women (n = 602) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | |

| Age (years)a | 66 (7) | 67 (6) |

| Weight (kg)a | 81.2 (12.0) | 73.4 (11.0) |

| Height (m)a | 1.66 (0.06) | 1.55 (0.06) |

| Waist circumference (cm)a | 104 (12) | 102 (12) |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 29.5 (3.8) | 30.7 (4.4) |

| Physical activity (kcal/day)a | 220 (217) | 136 (126) |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day)a | 2,384 (669) | 2,117 (614) |

| Total fat intake (% energy) | 38.7 (7.6) | 39.1 (6.9) |

| Carbohydrates (% energy) | 41.8 (7.9) | 42.6 (6.9) |

| Proteins (% energy)a | 16.3 (2.7) | 17.4 (2.7) |

| Alcohol (g/day)a | 11.7 (14.9) | 2.6 (4.8) |

| Total dairy products (g/day)a | 322 (194) | 395 (230) |

| Whole-fat milk (g/day)a | 43 (123) | 35 (120) |

| Partially skimmed milk (g/day) | 103 (153) | 127 (189) |

| Skimmed milk (g/day)a | 77 (145) | 115 (191) |

| Whole-fat yoghurt (g/day) | 22 (54) | 21 (56) |

| Skimmed yoghurt (g/day)a | 37 (64) | 56 (80) |

| Total cheese (g/day) | 31 (23) | 34 (28) |

| Lactose (g/day)a | 13 (9) | 16 (10) |

| Nonconsumers of milk (%) | 14.2 | 14.0 |

| Current smokers (%)a | 27.8 | 4.1 |

| Obesity (%)a | 42.4 | 53.5 |

| Diabetes (%)a | 54.4 | 41.9 |

| Metabolic syndrome (%)a | 53.5 | 66.8 |

| LCT (−13910C>T) genotype (%) | ||

| CC (LNP) | 39.3 | 37.2 |

| CT (LP) | 43.5 | 47.0 |

| TT (LP) | 17.2 | 15.8 |

The metabolic syndrome was defined according to updated ATP III criteria.

LP, lactase persistence; LNP, lactase nonpersistence.

Statistically significant differences between men and women (Student’s t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test for dairy products, alcohol, and physical activity. χ2-tests for categorical variables.

Prevalence of the LCT −13910 C>T genotypes were: CC (LNP) 38.0% (n = 357), CT 45.7% (n = 430), and TT 16.3% (n = 153). Carriers of the T allele were the genetically determined LP subjects. This distribution was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.221) and did not differ between men and women (P = 0.577).

Association between the −13910C>T polymorphism and dairy product intake

Table 2 shows mean intake of milk and dairy products (total and by gender) depending on the LCT −13910 C>T genotypes. The results are shown grouping the T carriers together (LP) and comparing them with CC subjects (LNP). Total energy intake did not differ between CC and subjects carrying the T-allele. Likewise, we did not find significant differences in physical activity depending on the LCT genotype (not shown). On analyzing the results for men and women jointly, it is observed that although dairy product consumption tended to be lower in CC subjects, the differences did not reach statistical significance. Neither was the total consumption of milk or the contribution of lactose or calcium through dairy products lower. Statistically significant differences were only reached in the consumption of skimmed yoghurt, which was lower in CC subjects.

Table 2.

Association of the LCT −13910C>T polymorphism with dairy product consumption in the elderly Mediterranean population

| Whole population | Men | Women | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT+TT | CC | CT+TT | CC | CT+TT | ||||||||||

| LNP (n = 357) | LP (n = 583) | LNP (n = 133) | LP (n = 205) | LNP (n = 283) | LP (n = 378) | ||||||||||

| Mean | (s.d.) | Mean | (s.d.) | P | Mean | (s.d.) | Mean | (s.d.) | P | Mean | (s.d.) | Mean | (s.d.) | P | |

| Age (years) | 68 | (6) | 67 | (6) | 0.075 | 67 | (6) | 66 | (7) | 0.472 | 68 | (6) | 67 | (6) | 0.153 |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 2,228 | (646) | 2,204 | (648) | 0.599 | 2,405 | (684) | 2,371 | (661) | 0.617 | 2,122 | (600) | 2,114 | (623) | 0.882 |

| Total dairy products (g/day) | 354 | (199) | 378 | (232) | 0.124 | 330 | (187) | 317 | (199) | 0.387 | 369 | (204) | 411 | (242) | 0.045 |

| Whole-fat milk (g/day) | 46 | (135) | 33 | (112) | 0.068 | 45 | (114) | 42 | (129) | 0.440 | 47 | (146) | 29 | (102) | 0.088 |

| Partially skimmed milk (g/day) | 112 | (165) | 123 | (184) | 0.642 | 108 | (160) | 101 | (149) | 0.855 | 115 | (169) | 135 | (199) | 0.491 |

| Skimmed milk (g/day) | 97 | (166) | 104 | (183) | 0.942 | 84 | (147) | 73 | (144) | 0.292 | 105 | (176) | 121 | (199) | 0.434 |

| Condensed milk (g/day) | 0 | (2) | 0 | (2) | 0.311 | 0 | (1) | 0 | (1) | 0.589 | 0 | (3) | 0 | (2) | 0.639 |

| Total milk (g/day) | 255 | (182) | 260 | (199) | 0.856 | 237 | (162) | 215 | (174) | 0.125 | 266 | (193) | 284 | (207) | 0.468 |

| Whole-fat yoghurt (g/day) | 21 | (52) | 21 | (57) | 0.541 | 27 | (60) | 19 | (50) | 0.204 | 18 | (47) | 23 | (60) | 0.818 |

| Skimmed yoghurt (g/day) | 39 | (61) | 55 | (82) | 0.004 | 29 | (55) | 42 | (70) | 0.150 | 46 | (64) | 62 | (87) | 0.016 |

| Skimmed milk and yoghurt (g/day) | 248 | (201) | 318 | (239) | 0.053 | 221 | (186) | 216 | (185) | 0.762 | 265 | (208) | 318 | (239) | 0.014 |

| Whipped cream (g/day) | 0 | (1) | 0 | (5) | 0.305 | 0 | (1) | 1 | (7) | 0.699 | 0 | (1) | 0 | (2) | 0.321 |

| Milkshake (g/day) | 1 | (10) | 1 | (15) | 0.478 | 1 | (14) | 1 | (7) | 0.259 | 1 | (6) | 2 | (18) | 0.975 |

| Ricotta cheese or curd (g/day) | 2 | (8) | 1 | (8) | 0.378 | 1 | (7) | 1 | (9) | 0.991 | 2 | (9) | 1 | (8) | 0.268 |

| Petit Suisse cheese (g/day) | 1 | (5) | 0 | (3) | 0.717 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0.980 | 1 | (6) | 0 | (3) | 0.927 |

| Spreadable cheese wedges (g/day) | 1 | (3) | 1 | (5) | 0.646 | 1 | (3) | 1 | (4) | 0.602 | 1 | (2) | 1 | (5) | 0.323 |

| Cottage cheese (g/day) | 13 | (14) | 16 | (20) | 0.101 | 9 | (11) | 13 | (18) | 0.296 | 15 | (16) | 17 | (21) | 0.274 |

| Other cheese (hard cheese) (g/day) | 16 | (18) | 15 | (15) | 0.739 | 18 | (18) | 16 | (14) | 0.706 | 15 | (18) | 14 | (15) | 0.914 |

| Custard (g/day) | 3 | (12) | 3 | (9) | 0.615 | 4 | (13) | 4 | (11) | 0.324 | 3 | (11) | 2 | (7) | 0.805 |

| Ice cream (g/day) | 2 | (5) | 3 | (15) | 0.873 | 2 | (4) | 5 | (21) | 0.966 | 2 | (5) | 2 | (10) | 0.755 |

| Lactose (g/day) | 14 | (9) | 15 | (10) | 0.441 | 13 | (8) | 13 | (9) | 0.311 | 15 | (10) | 17 | (11) | 0.115 |

Statistically significant values are presented in boldface.

P values for the comparison of means between CC and CT+TT subjects for dairy products were carried out by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test.

LP, lactase persistence; LPN, lactase nonpersistence.

On analyzing the results per gender, it can be observed that in men the differences in milk and dairy product intake depending on genotype were minimal and did not reach statistical significance for any comparison. In women, these differences were more accentuated; reaching statistical significance in the consumption of skimmed yoghurt (lower in CC subjects) and when the consumption of skimmed yoghurt, skimmed milk, and partially skimmed milk were analyzed together (265 ± 208 g/day vs. 318 ± 239 g/day in CC vs. CT+TT; P = 0.014). Likewise, the total consumption of dairy products also reached statistically significant differences in women depending on the LCT genotype (P = 0.045). No significant differences of lactose intake were found.

We further analyzed whether the LCT −13910 C>T polymorphism predicted complete milk abstinence. A logistic regression model in which the 14% nonconsumers were compared to all the others was fitted. After adjustment for sex, the LCT genotype was not significantly associated with milk abstinence (OR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.54–1.20; P = 0.279 for CC in comparison with T-allele carriers).

Association between the −13910C>T SNP with anthropometric variables

We observed that the −13910C>T SNP presented a strong association with anthropometric measures (Table 3). CC individuals, although they do not differ in height from the other genotypes, had significantly less weight, a lower BMI and less waist circumference than T-allele carriers. These differences remained statistically significant when the models were adjusted for gender and age, and even after additional adjustment for diabetes, physical activity, and total energy intake. These associations were homogeneous by gender, and both in men and women CC subjects have lower means of anthropometric measurements than T-allele carriers (P for interaction LCT genotype × gender were 0.738, 0.872, and 0.942 for weight, BMI, and waist circumference, respectively).

Table 3.

Association of the LCT −13910 C>T polymorphism with anthropometric variables

| CC | CT+TT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNP (n = 357) | LP (n = 583) | ||||

| Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | P1 | P2 | P3 | |

| Age (years) | 67.5 (6.1) | 66.8 (6.1) | 0.080 | ||

| Height (m) | 1.59 (0.08) | 1.59 (0.08) | 0.392 | 0.314 | 0.333 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.2 (12.3) | 76.8 (11.7) | 0.044 | 0.032 | 0.021 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.7 (4.2) | 30.6 (4.2) | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.1 (11.8) | 103.5 (11.5) | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Obesity prevalence (%) | 45.4 | 53.7 | 0.014 | ||

| OR for obesity and (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.39 (1.07–1.82) | 0.014 | ||

| 1.39 (1.06–1.81) | 0.017 | ||||

| 1.37 (1.03–1.81) | 0.029 |

CI, confidence interval; LP, lactase persistence; LPN, lactase nonpersistence; OR, odds ratio; P1, unadjusted P value; P2, model adjusted for sex and age; P3, model adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, total energy intake, and physical activity.

Next, we analyzed the association of the −13910C>T SNP with obesity (Table 3). Considering CC individuals as the reference category, we observed that T-allele carriers have a greater risk (OR) of obesity, both unadjusted (OR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.07–1.82; P = 0.014) and after adjustment for gender, age, diabetes, physical activity, and total energy intake (OR: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.03–1.81; P = 0.029). Homogeneity by gender was also observed between men and women in this association (P for interaction LCT × gender = 0.826). Subsequent adjustments for dairy product intake do not modify the statistical significance of the associations of the −13910 C>T SNP with the anthropometric variables (data not shown).

Modulation of the association between the −13910C>T SNP with anthropometric variables by lactose intake

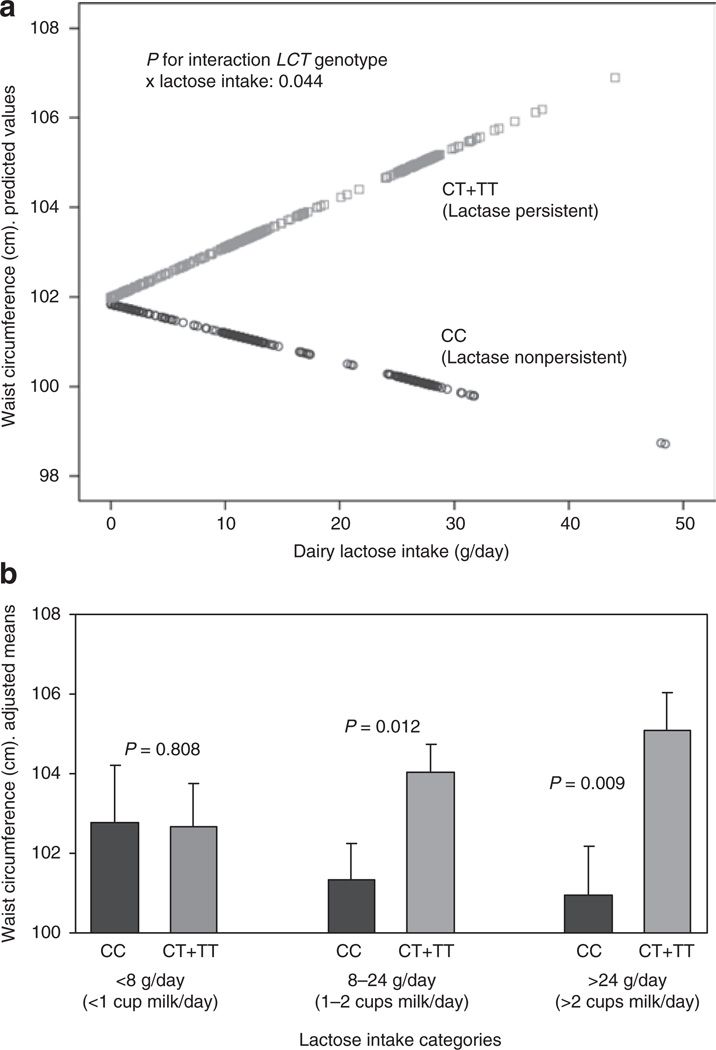

Considering that CC subjects may tolerate low amounts of lactose intake without gastrointestinal symptoms, we hypothesized that dairy lactose intake may modulate the effects of the −13910 C>T SNP on anthropometric variables. We first tested the interaction effect between the −13910 C>T SNP and dairy lactose intake as continuous. Taking into account that dairy lactose intake was not normally distributed, eight identified outliers (corresponding to 8 TC+TT subjects with lactose intake higher that 50 g/day) were removed to improve normality for this linear regression analysis. We found a statistically significant interaction term between lactose intake and the −13910 C>T SNP in determining waist circumference (P = 0.044 after adjustment for sex, age, diabetes, total energy intake, and physical activity). According to this interaction, a higher dairy lactose intake increased the differences in waist circumference between CC and CT+TT individuals (Figure 1a). We also tested this modulation by lactose intake as a categorical variable. Three categories of lactose intake based on habitual milk consumption equivalence were considered (Figure 1b). No differences in the −13910 C>T genotype distribution among categories (low, intermediate, and high) of lactose intake (P = 0.518) were observed. When lactose intake was low (less than 1 small cup per day (≤8 g lactose/day); 20% of the population), we did not find significant differences in waist-circumference between CC and T-allele carriers (P = 0.808). When lactose intake was intermediate (between 1 and 2 small or large cups of milk per day (8–24 g lactose/day); 50% of the population), significant differences in waist circumference between LCT genotypes were detected (P = 0.012). These differences increased in magnitude (P = 0.009) when higher intakes of lactose were observed (>2 large cups of milk per day (>24 g lactose/day); 30% of the population).

Figure 1.

Modulation by dairy lactose intake of the association between the LCT −13910C>T polymorphism and waist circumference (cm) in the elderly Mediterranean population. (a) Predicted values of waist circumference by the LCT −13910C>T (n = 357 CC individuals and n = 576 T-allele carriers (eight outliers with lactose intake >50 g/day were removed to improve normality for the statistical analysis) depending on the lactose consumed (as continuous) are depicted. Predicted values were calculated from the regression models containing lactose intake, the LCT polymorphism, their interaction term, and the potential confounders (sex, age (as continuous), diabetes (as categorical), total energy intake (as continuous), and physical activity (as continuous)). Predicted values for this model were obtained for each individual. The P value for the interaction term was obtained in the multivariate interaction model. (b) Adjusted means of waist circumference (cm) in the study subjects (n = 940) depending on the LCT −13910C>T polymorphism according to three strata of lactose intake: low (≤8 g lactose/day; 20% of the population (n = 68 CC, 122 CT+TT)), intermediate (8–24 g lactose/day; 50% of the population (n = 188 CC, 284 CT+TT)), and high (>24 g lactose/day; 30% of the population (n = 101 CC, 177 CT+TT)). Estimated means were adjusted for sex, age (as continuous), diabetes (as categorical), total energy intake (as continuous), and physical activity (as continuous). P values for genotype comparisons in each strata were estimated after multivariate adjustment for the covariates indicated above. Bars indicate s.e. of means.

In terms of obesity risk, in subjects with a low lactose intake (≤8 g/day) we did not find significant association between the −13910 C>T SNP and obesity in the crude model (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.55–1.91; P = 0.910) or in the model adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, physical activity, and total energy intake (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.54–2.01; P = 0.891). However, when lactose intake was higher (>8 g/day), we did observe a significant association of the CT+TT genotype with higher obesity risk (OR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.10–2.03; P = 0.012 in the crude model and OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.05–1.96; P = 0.022 in the model adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, physical activity, and total energy intake).

Association between the −13910C>T SNP with the metabolic syndrome related variables

Finally, we studied the association of the −13910C>T SNP with biochemical parameters (fasting glucose and plasma lipids) and blood pressure (Table 4) and observed that, after adjustment for BMI and other potential confounders, there were no statistically significant differences in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose concentrations, or blood pressure between CC subjects and T-allele carriers. When we analyzed the association of the −13910C>T SNP with the metabolic syndrome, taking CC individuals as the reference category, although the magnitude of the OR in T-allele carriers was >1, it did not reach statistical significance, either adjusted for gender and age (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 0.95–1.68; P = 0.114) or after additional adjustment for physical activity and total energy intake (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.92–1.67; P = 0.164). When we tested the potential modulation by lactose intake, we found that in subjects with a low lactose intake (≤8 g/day), the LCT SNP was not associated with the metabolic syndrome (OR adjusted for sex, age, physical activity, and energy intake: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.49–1.96; P = 0.955), this association being statistically significant in subjects with lactose intake higher than 8 g/day (OR adjusted for sex, age, physical activity, and energy intake: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.02–1.90; P = 0.040). However, this association was mainly mediated by abdominal obesity. It was the only component of the metabolic syndrome that was significantly associated with the −13910C>T polymorphism.

Table 4.

Association of the LCT −13910 C>T polymorphism with plasma lipids, glucose, and blood pressure

| CC | CT+TT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNP (n = 357) | LP (n = 583) | |||

| Mean (s.e.) | Mean (s.e.) | P1 | P2 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 206.6 (2.2) | 204.4 (1.8) | 0.418 | 0.531 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 129.67 (2.09) | 127.10 (1.64) | 0.324 | 0.367 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 51.3 (0.7) | 52.1 (0.6) | 0.349 | 0.311 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 136.7 (4.6) | 129.3 (3.6) | 0.198 | 0.305 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl)a | 121.3 (1.8) | 121.7 (1.4) | 0.868 | 0.731 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 146.3 (1.2) | 147.4 (0.9) | 0.422 | 0.359 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 81.7 (0.7) | 82.6 (0.5) | 0.309 | 0.154 |

Means were adjusted for sex, age, and BMI.

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LP, lactase persistence; LPN, lactase nonpersistence; P1, P value for the LCT genotype obtained in the model adjusted for sex, age, BMI (and diabetes for fasting glucose); P2, P value for the LCT genotype obtained in the models additionally adjusted for medications (lipid lowering drugs, antihypertensives and diabetes medication).

Means were additionally adjusted for diabetes.

DISCUSSION

Although in this Mediterranean population, the effect of the −13910C>T polymorphism on milk and dairy product consumption was not very high, we have found a relevant association with anthropometric measurements. CC individuals had significantly lower BMI, lesser waist circumference and lower risk of obesity than T-allele carriers even after adjustment for sex, age, diabetes, physical activity, and total energy intake. Moreover, we reported for the first time that the association between the LCT −13910C>T SNP and anthropometric variables is modulated by dairy lactose intake. These observations are in line with the results obtained in a recent meta-analysis (23) in which the LCT −13910C>T polymorphism was associated with BMI in 31,720 European individuals (including five cohorts of Finnish origin (with a high milk intake), and three from Holland and England). In this study, the CC genotype was associated with decreased BMI compared to CT/TT genotypes and discarded population stratification as being responsible for these effects. In our study, the probability of the influence of population stratification is very low, as we carried it out on ethnically homogenous subjects recruited in a single region of Spain. A study undertaken on postmenopausal Spanish women (28) found a significant association between this SNP and weight, however, the authors did not analyze differences in waist circumference or obesity risk. Our results also replicate the observations of the CHARGE Consortium, where strong associations were found between SNPs in the LCT gene and waist-circumference (22).

In line with those observations, a study in the general population of the Canary Islands (29) found a greater risk of metabolic syndrome in CT+TT than in CC subjects (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.06–2.31). We observed a similar tendency, but our results did not reach statistical significance in the whole population given that we detected associations mainly with anthropometric measurements and not with biochemical variables. Since a high number of subjects are being treated with medications, there is a possibility that the lack of association with plasma lipids, glucose, or blood pressure can be due to the influence of the medications. However, in subgroup analysis we observed a significant association between the metabolic syndrome and the LCT SNP in subjects with lactose intake >8 g/day.

On the other hand, we found no significant differences in the amount of total milk consumed depending on the −13910C>T SNP. Possibly, on dealing with an elderly population, medical advice recommending higher milk consumption to minimize osteoporosis may have a greater influence, that recommendation offsetting the genetic influence. Other studies that have analyzed the influence of the −13910C>T SNP on milk and dairy product consumption have also found differing associations depending on the age and gender of the population analyzed (16–21,29–33). It seems that the influence of this polymorphism on dairy consumption is higher in women than in men. One possible explanation could be that females and males differ in their sensitivity to gastrointestinal symptoms caused by lactose, being stronger in women (34). Another possible explanation could be that as men consume less milk than women in this population, the amount of lactose does not pose a problem even for the LNP, as it has been reported that gastrointestinal symptoms are not important until consuming amounts >12 g of lactose/day (35). Other authors indicate that lactose maldigesters may be able to tolerate foods containing 6 g lactose or less, such as small servings (120 ml or less) of milk (36). In our study, we did not find differences in the prevalence of the LP or LNP genotypes among the three categories of lactose intake considered. In addition to differences in abdominal pain, bloating, or diarrhea that may be related to less weight (10), some studies have shown differences in the microbial composition of fecal samples of the LP and LNP individuals (37,38) that may relate to obesity even in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms. Szilagyi et al. (38), observed that LNP had differences in bifidobacteria and lactobacilli counts compared with lactose digesters. Bearing in mind that recent studies have shown differences between the gut microbiota in obese and nonobese individuals (39–41), changes in the gut microbiota in LNP compared with LP subjects may be involved in differences in caloric extraction of ingested food and the lower risk of obesity observed in CC individuals, due to differing lactose fermentation capacity and the subsequent multiple effects.

Overall, our hypothesis, as well as the identification of additional mechanisms to explain the association of the LCT SNP with obesity-related variables, requires further studies in order to substantiate it. Supporting this hypothesis is our observation of a possible greater effect of the LCT −13910C>T SNP on anthropometric measurements when the amounts of lactose consumed are greater. When dairy lactose intake was very low, we did not find significant differences in waist circumference or obesity risk between CC and T-allele carriers. However, significant differences in were found with higher lactose intake. This is the first time that a modulation by the amount of lactose intake of the effects of the LCT −13910C>T SNP on obesity is reported and requires replication in other populations. One of the limitations of our study is that it has been carried out on an elderly high cardiovascular risk population and therefore cannot be generalized to healthy or younger populations. In addition, the use of current dietary data may not reflect longer-term dietary patterns that have contributed to current anthropometric or metabolic measures. Likewise, some recommendations to lose weight in obese patients (for example, consumption of skimmed milk) may have influenced milk consumption patterns in this population.

In conclusion, we have replicated the association between the LCT −13910C>T SNP and BMI in a Mediterranean population and reported for the first time a modulation of the effects by lactose intake. Our findings also suggest that some of the controversial results obtained in previous studies investigating the association of dairy products on obesity-related variables may be explained by the potential heterogeneous effects of these products on LNP and LP individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain (CIBER CB06/03/0035, RD07/0067/0006, PI6-1326, PI07-0954, PI08-90002, and SAF-09-12304), the Generalitat Valenciana, Spain (GVACOMP2010-181, BEST2010-211, BEST2010-032) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL-54776, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grant number DK075030 and by contracts 53-K06-5-10 and 58–1950-9-001 from the US Department of Agriculture Research.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Jr, Van Horn L, et al. Dairy consumption, obesity, and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: the CARDIA Study. JAMA. 2002;287:2081–2089. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dairy consumption and body mass index: an inverse relationship. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:115–121. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dairy consumption is inversely associated with the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:523–530. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elwood PC, Pickering JE, Fehily AM. Milk and dairy consumption, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: the Caerphilly prospective study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:695–698. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snijder MB, van Dam RM, Stehouwer CD, et al. A prospective study of dairy consumption in relation to changes in metabolic risk factors: the Hoorn Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:706–709. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wennersberg MH, Smedman A, Turpeinen AM, et al. Dairy products and metabolic effects in overweight men and women: results from a 6-mo intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:960–968. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamarche B. Review of the effect of dairy products on non-lipid risk factors for cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:741S–746S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.German JB, Gibson RA, Krauss RM, et al. A reappraisal of the impact of dairy foods and milk fat on cardiovascular disease risk. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warensjo E, Nolan D, Tapsell L. Dairy food consumption and obesity-related chronic disease. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2010;59:1–41. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(10)59001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suchy FJ, Brannon PM, Carpenter TO, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference: lactose intolerance and health. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:792–796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enattah NS, Sahi T, Savilahti E, et al. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat Genet. 2002;30:233–237. doi: 10.1038/ng826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olds LC, Sibley E. Lactase persistence DNA variant enhances lactase promoter activity in vitro: functional role as a cis regulatory element. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2333–2340. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewinsky RH, Jensen TG, Møller J, et al. T-13910 DNA variant associated with lactase persistence interacts with Oct-1 and stimulates lactase promoter activity in vitro. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3945–3953. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohl D, Savarino E, Hersberger M, et al. Excellent agreement between genetic and hydrogen breath tests for lactase deficiency and the role of extended symptom assessment. Br J Nutr. 2010;19:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swallow DM. Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annu Rev Genet. 2003;37:197–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehtimäki T, Hemminki J, Rontu R, et al. The effects of adult-type hypolactasia on body height growth and dietary calcium intake from childhood into young adulthood: a 21-year follow-up study–the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1553–1559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laaksonen MM, Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, et al. Genetic lactase non-persistence, consumption of milk products and intakes of milk nutrients in Finns from childhood to young adulthood. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:8–17. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508184677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torniainen S, Hedelin M, Autio V, et al. Lactase persistence, dietary intake of milk, and the risk for prostate cancer in Sweden and Finland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:956–961. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gugatschka M, Hoeller A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, et al. Calcium supply, bone mineral density and genetically defined lactose maldigestion in a cohort of elderly men. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30:46–51. doi: 10.1007/BF03347395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gugatschka M, Dobnig H, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, et al. Molecularly-defined lactose malabsorption, milk consumption and anthropometric differences in adult males. QJM. 2005;98:857–863. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith GD, Lawlor DA, Timpson NJ, et al. Lactase persistence-related genetic variant: population substructure and health outcomes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:357–367. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heard-Costa NL, Zillikens MC, Monda KL, et al. NRXN3 is a novel locus for waist circumference: a genome-wide association study from the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kettunen J, Silander K, Saarela O, et al. European lactase persistence genotype shows evidence of association with increase in body mass index. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, et al. PREDIMED Study Investigators. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1808–1816. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mataix J. Tablas de Composición de Alimentos (Spanish Food Composition Tables) 4th edn. Granada (in Spanish): Universidad de Granada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agueda L, Urreizti R, Bustamante M, et al. Analysis of three functional polymorphisms in relation to osteoporosis phenotypes: replication in a Spanish cohort. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;87:14–24. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almon R, Alvarez-Leon EE, Engfeldt P, et al. Associations between lactase persistence and the metabolic syndrome in a cross-sectional study in the Canary Islands. Eur J Nutr. 2010;49:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehtimäki T, Hutri-Kähönen N, Kähönen M, et al. Adult-type hypolactasia is not a predisposing factor for the early functional and structural changes of atherosclerosis: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Clin Sci. 2008;115:265–271. doi: 10.1042/CS20070360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sacerdote C, Guarrera S, Smith GD, et al. Lactase persistence and bitter taste response: instrumental variables and mendelian randomization in epidemiologic studies of dietary factors and cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:576–581. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almon R, Patterson E, Nilsson TK, Engfeldt P, Sjöström M. Body fat and dairy product intake in lactase persistent and non-persistent children and adolescents. Food Nutr Res. 2010;54 doi: 10.3402/fnr.v54i0.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laaksonen MM, Impivaara O, Sievänen H, et al. Associations of genetic lactase non-persistence and sex with bone loss in young adulthood. Bone. 2009;44:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vesa TH, Seppo LM, Marteau PR, Sahi T, Korpela R. Role of irritable bowel syndrome in subjective lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:710–715. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilt TJ, Shaukat A, Shamliyan T, et al. Lactose intolerance and health. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2010:1–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hertzler SR, Huynh BC, Savaiano DA. How much lactose is low lactose? J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:243–246. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong Y, Priebe MG, Vonk RJ, et al. The role of colonic microbiota in lactose intolerance. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:78–83. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000011606.96795.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szilagyi A, Shrier I, Heilpern D, et al. Differential impact of lactose/lactase phenotype on colonic microflora. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:373–379. doi: 10.1155/2010/649312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armougom F, Henry M, Vialettes B, Raccah D, Raoult D. Monitoring bacterial community of human gut microbiota reveals an increase in Lactobacillus in obese patients and Methanogens in anorexic patients. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanz Y, Santacruz A, Gauffin P. Gut microbiota in obesity and metabolic disorders. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:434–441. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110001813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]