Abstract

Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) has found significant use in evaluating long-term cancer therapy in small animals. We have now tested the feasibility of using BLI to assess acute effects of the vascular disrupting agent Combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P) on luciferase expressing MDA-MB-231 human breast tumor cells growing as xenografts in mice. Following administration of luciferin substrate, there is a rapid increase in light emission reaching a maximum after about six minutes, which gradually decreases over the following 20 min. The kinetics of light emission are highly reproducible, however, following IP administration of CA4P (120 mg/kg), the detected light emission was decreased between 50 and 90 percent and time to maximum was significantly delayed. Twenty-four hours later, there was some recovery of light emission following further administration of luciferin substrate. Comparison with dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI based on the paramagnetic contrast agent Omniscan showed comparable changes in the tumors consistent with the previous literature. Histology also confirmed shutdown of tumor vascular perfusion. We believe this provides an important novel application for BLI, which could have widespread application in screening novel therapeutics expected to cause acute vascular changes in tumors.

Keywords: breast tumor, imaging, vascular targeting agent, vascular disrupting agent, pharmacodynamics

Introduction

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) has found a major role in small animal research (1–3). For tumor cells transfected to constitutively express luciferase, there are numerous reports examining tumor growth and metastatic spread (4, 5). Bioluminescence imaging has also found widespread use in examining changes in tumor growth over a period of many weeks with diverse therapies (6–10). Bioluminescent imaging requires administration of luciferin substrate, which may be achieved by multiple routes including intravenous (IV), intra peritoneal (IP) or subcutaneous (SC) (11, 12). Luciferin is then carried throughout the vasculature and has been shown to readily permeate every region of the body (9, 13, 14). Given the importance of vascular transport, it occurred to us that the measurement of the light-emitting dynamics would be related to vascular delivery of the substrate. Thus, any agent causing major acute affects on tumor vasculature could influence the light emission kinetics. In particular, it appeared that vascular targeting agents (VTAs) (also referred to as vascular disrupting agents) such as Combretastatin, could be assessed based on the dynamics of light emission detected by BLI.

Tumor growth, survival, and metastasis depend critically on the development of new blood vessels (15). Therefore, extensive research has focused on developing strategies to attack tumor vasculature (16–19). Tubulin binding agents, e.g., Combretastatin A-4-phosphate (CA4P) and ZD6126 represent one kind of vascular targeting agent (VTA) (17). Promising preclinical studies have shown that such agents selectively cause tumor vascular shutdown and subsequently trigger a cascade of tumor cell death in experimental tumors (20). Although massive necrosis can be induced, tumors usually regrow from a thin viable rim. To better understand the mode of action, and hence, facilitate optimized therapeutic combinations, in vivo imaging approaches have been applied to monitor physiological changes resulting from VTA administration (21–23). Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI based on the transport properties of the small paramagnetic contrast agent gadolinium-DTPA (Gd-DTPA) is the most commonly used imaging approach to study tumor vascular perfusion and permeability. DCE MRI was included as part of the Phase I clinical trials of CA4P (24, 25). Results of preclinical and clinical DCE MRI studies have shown a reversible change in vascular perfusion in the tumor periphery following a single dose of VTA (26–29).

The vascular targeting agent, Combretastatin A-4-phosphate (CA4P) causes tumor vascular shutdown inducing massive cell death. We recently showed acute hypoxiation within 90 mins following CA4P administration to rats bearing syngeneic breast 13762NF tumors using MRI (30). Rapid vascular shut-down in tumors after administration of CA4P to animals and patients has also been observed by many other imaging modalities including positron emission tomography (PET) based on the distribution of 15O water (31), DCE MRI (24, 32, 33), DCE computed tomography (CT) (34), 19F MRI of tumor oxygenation (30), Laser Doppler flowmetry (35), radiolabeled iodoantipyrine (IAP) uptake (27), near infrared spectroscopy (36), interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) (35) and intra vital microscopy (37). By comparison bioluminescence imaging is particularly inexpensive and easy to apply in animal models and we believe it could be an effective screening tool for evaluation and comparison of vascular targeting agents as well as long-term tumor growth. Bioluminescence imaging is exceedingly sensitive with the capability of detecting sub-palpable tumor volumes.

We have now explored the ability of planar BLI, a widely available modality, to investigate the acute effects of CA4P on human breast MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors and provide correlates with the more traditional magnetic resonance (MRI) approach and histology.

Materials and Methods

Tumor model

Human mammary MDA-MB-231 cells were infected with a lentivirus containing a firefly luciferase reporter and highly expressing stable clones were isolated. Tumors were induced by injecting 106 cells subcutaneously in the flank of 13 athymic nude mice (BALB/c nu/nu; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Tumors were allowed to grow to about 6 mm diameter (~ 100 mm3) and then selected for BLI or MRI.

In vivo BLI

Tumor-bearing mice were anesthetized (O2, isoflurane (Baxter International Inc., Deerfield, IL)/O2 in an induction chamber) and a solution of D-luciferin (Biosynthesis, Naperville, IL; 450 mg/kg in PBS in a total volume of 250 μl) was administered SC in the neck region. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (1%) in oxygen (1 dm3/min) and a series of light images (30 s each) was acquired using a single reference camera of our multi-camera Light Emission Tomography System (mLET) over a period of 20 – 30 mins and the light intensity–time curves evaluated.

The imaging system uses CCD (charge-coupled device) cameras selected for their high and nearly constant sensitivity over the full range of wavelengths commonly used in optical imaging, from blue to near infrared. The CCD is a non-color, back-illuminated, full frame image sensor with 512×512 pixels, (Scientific Imaging Technologies Inc., Tigard, OR, (SITe) SI-032AB CCD). The quantum efficiency of the CCD is greater than 85% from 400 nm to 750 nm, and remains above 50% up to 900 nm. The CCD has a pixel size of 24×24 μm providing a large well capacity of 350,000 e−, with a sensitivity of 2.6 μV/e−, low dark current (20 pA/cm2 at 20 °C), and low readout noise (5 e− RMS) providing a dynamic range of 75,000. The CCD is cooled to −40° C reducing the dark current signal to less than 0.1 e−/pixel/s. The large dynamic range of the detector is coupled with a 16 bit analog to digital (A/D) converter, allowing quantitative detection of both high and very low signals, simultaneously. The CCD is incorporated in a self-contained, cooled camera, equipped with electronic circuitry and fast optics (25 mm focal length, f/0.95). Each camera is calibrated using a low-intensity, diffuse, flat field source that gives a known radiance (adjusted typically at 3.0 × 10−7 W/cm2/sr). The light source is periodically checked for uniformity using a NIST-traceable research radiometer (model IL 1700, International Light, Inc. Newburyport, MA). By imaging this source the digital units provided by the camera digitizer can be converted directly into absolute physical units (W/cm2/sr or photons/s/cm2/sr).

Saline control or Combretastatin A4P (CA4P; 120 mg/kg; OXiGENE, Inc. Waltham, MA) in saline (120 μl) was injected IP immediately after baseline BLI and the mouse allowed to wake up. Two hours and 24 h later the BLI time course was repeated based on new injections of luciferin. In some cases mice were examined again 24 h after CA4P administration.

In vivo MRI

A second cohort of nude mice (n= 3) with size-matched tumors was studied by MRI using a 4.7 T horizontal bore magnet with a Varian INOVA Unity system (Palo Alto, CA). Each mouse was maintained under general anesthesia (air and 1% isoflurane). A 27 G butterfly (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) was placed in a tail vein for contrast agent administration. Pertinent image slice positions were based on fast scout images. T1- (TR = 200 ms; TE = 15 ms; slice thickness = 1.5 mm; FOV = 50 × 50; in plane resolution 390 μm) and corresponding T2-weighted (TR = 1500 ms; TE = 80 ms) spin-echo multi-slice (SEMS) axial images were acquired. For dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI, a series of three contiguous T1-weighted images (TR = 70 ms; TE = 12 ms; total acquisition time 10 s with same voxels dimensions as above) was acquired before and after IV bolus injection of the contrast agent Gd-DTPA-BMA (0.1 mmol/kg body weight; Omniscan™, Amersham Health Inc., Princeton, NJ) through a tail vein catheter. DCE MRI was performed before and 2 h after CA4P infusion (120 mg/kg, IP).

Data were processed on a voxel-by-voxel basis using software written by us using IDL 5.3/5.4 (Research Systems, Boulder, CO). For each slice, the tumor was separated into regions of center and periphery, respectively. The tumor periphery was taken to be a 1–2 mm thick rim aligned around the whole tumor. Signal intensity versus time curves were plotted and relative signal intensity changes (ΔSI) of each tumor voxel were analyzed using the equation: (ΔSI) = (SIE − SIb)/SIb, where SIE refers to enhanced signal intensity in the voxel and SIb is defined as the average of the baseline images. The area under the normalized signal intensity-time curve (IAUC) was integrated for the first 60 s after Gd-DTPA-BMA injection.

Immunohistochemistry

Two hours after saline or CA4P injection, the blue fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 (10 mg/kg, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was injected into the tail vein of anesthetized mice and the tumors were excised 1 min later. Tumor specimens were immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C. A series of 6 μm frozen sections from several regions of each tumor was immunostained for luciferase (Serotec Inc. Raleigh, NC). Slices were imaged for Hoechst 33342 under UV wavelength (330–380 nm). Perfused vessels were determined by counting the total number of structures stained by Hoechst 33342 in four fields per section selected to show high perfusion and calculating the mean number of vessels per mm2. On the following day, the same slices, as well as the adjacent ones, were immunostained for the endothelial marker, CD31. A primary rat anti mouse CD31 monoclonal antibody (1:20 dilution; Serotec, Raleigh, NC) was added and incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humid box. Slides were incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat anti rat secondary antibody (1:100 dilution; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at 37 °C. After mounting with Vectorshield® medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), the slides were observed under red fluorescence (530–550 nm excitation) to detect anti-CD-31 and then the corresponding Hoechst 33342 again under UV light. Image analysis was performed using Metaview software (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, PA). For luciferase staining monoclonal mouse anti-luciferase mAb (1:150, Serotec) and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson Labs) were used.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was assessed using an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the basis of Fisher’s Protected Least Significant Difference (PLSD; Statview, SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC) or Student’s t-tests.

Results

Histology of MDA-MB-231-luc cells showed extensive expression of luciferase detected by anti-luc mAb in all tumor cells (Figure 1). Bioluminescent imaging showed intense light emission from tumors following SC administration of luciferin reaching a maximum intensity about 6 mins post administration followed by a gradual decline over the next 20 mins. Repeat measurements following administration of a second dose of luciferin 2 h after injecting saline IP showed highly reproducible results (Figure 1, Table 1), in terms of light distribution, maximum light intensity and time to maximum light emission. Five tumors were examined again after 24 h and light emission remained highly consistent with mean maximum intensity = 97±6% (range 49 to 130 %). By contrast repeat BLI 2 h after treatment with CA4P showed a significantly lower light emission (peak intensity 2 to 10 times lower) and delayed peak emission (Figure 2, Table 1). Three mice were examined again 24 h post CA4P and signal was again significantly lower than baseline (mean 41±5, range 21–66%), though with some recovery compared with 2 h. Histology showed a well developed well perfused vasculature in these tumors, but perfusion was essentially eliminated 2 h after administration of CA4P IP (Figure 3).

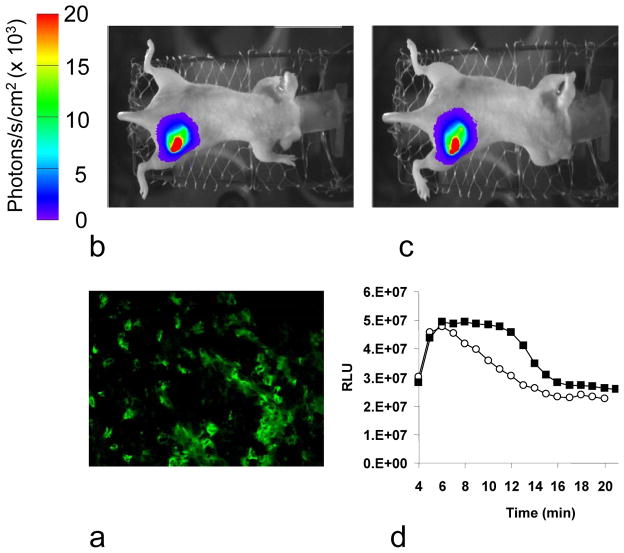

Figure 1. Control BLI dynamic measurement.

a) Staining for luciferase in an MDA-MB-231-luc tumor tissue section showed extensive fluorescent mAb signal predominantly located in cytoplasm of many tumor cells.

b) Bioluminescent image from a representative MDA-MB-231-luc tumor (140 mm3) acquired in 1 min, 4 mins after luciferin injection (450 mg/kg SC).

c) Bioluminescent image from the same tumor following repeat SC luciferin injection two hours after saline injection (0.15 ml IP).

d) The BLI intensity was integrated over the whole tumor and the time course was essentially identical for the two investigations conducted 2 h apart with respect to saline administration, as a control. Maximum signal intensity was observed at 6 min after SC luciferin administration.

Table 1. MDA-MB-231-luc mammary carcinoma response to CA4P observed by BLI.

Comparison of light emission at baseline and 2 h after administer of saline (control) or 120 mg/kg CA4P.

| Groups | # animal | Max RLU change (%) + | Time delay (min) # | AUC change (%) + | Signal change at 7 min (%) + | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± sd | range | mean ± sd | range | mean ± sd | range | mean ± sd | range | ||

| Saline | n = 6 | −16 ± 19 | −48 ~ 3 | 0.1 ± 1.2 | −0.1 ± 1.7 | 11 ± 20 | −20 ~ 31 | −18 ± 25 | −55 ~ 8 |

|

| |||||||||

|

CA4P 120 mg/kg |

n = 10 | −70 ± 15* | −53 ~ −92 | +7.1 ± 5.9 * | −2.2 ± 1.5 | −72 ± 16 ** | −42 ~ −93 | −76 ± 17 * | −97 ~ −53 |

AUC: Area under curve for 20 min;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

% change compared with baseline

Delay compared with baseline

Figure 2. Tumor response to CA4P monitored by planar BLI.

A second MDA-MB-231-luc tumor (130 mm3) was monitored sequentially following saline or CA4P (120 mg/kg) IP infusion. Each image was acquired in 1 min, 4 min after SC luciferin injection. In contrast to saline, CA4P treatment caused a significant decrease in BLI signal intensity 2 h after treatment, which remained lower 24 h later. a) Baseline control, b) 2 h after CA4P, c) 24 h after CA4P, d) BLI intensity curves showing intense signal pre treatment (solid squares) with 99% less signal two hours after CA4P (open circles).

Figure 3. Immunohistochemical study of tumor vascular response to CA4P.

Perfusion marker Hoechst 33342 staining pre- and 2 h post-CA4P (120 mg/kg). Vascular endothelium of the same field was immunostained by anti-CD31 (red). A good match between Hoechst and anti-CD31 stained vascular endothelium was found in the pretreated tumor (overlay). Two hours after treatment, significant reduction in perfused vessels was detected. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

Signal enhancement observed by DCE MRI was significantly less in all three tumors with a mean decrease of about 70% in perfusion/permeability 2 h after CA4P (p < 0.001, Table, Figure 4). Little change was observed in perfusion of the femoral artery (data not shown). Muscle in one mouse indicated a significant reduction in IAUC, but others showed no significant change (Table 2).

Figure 4. DCE MRI monitoring of tumor response to CA4P.

Top row: Conventional MR images of a nude mouse with an MDA-MB-231-luc mammary tumor (#2 in Table 2). a) T1- weighted, b) T2-weighted, and c) T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (Gd-DTPA-BMA).

Bottom row: Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI was performed in the mouse before (d, left) and 2 h after (e, right) CA4P IP injection. Color scale map representing normalized contrast enhancement 30 s after a bolus injection of Gd-DTPA-BMA is overlaid on the T1-weighted images. Significantly decreased signal enhancement, compared to pretreatment, was observed 2 h after IP injection of CA4P. f) Ratio of tumor to muscle signal enhancement following infusion of Gd-DTPA-BMA in the single image slice shown in d and e. Solid symbols: baseline; open symbols 2 hr after CA4P.

Table 2. Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI data.

IAUC was assessed across regions of interest corresponding to tumor and contralateral thigh muscle over three contiguous MR image slices.

| Tumor no. | IAUC60 (mean ± SE)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | Normal muscle | |||||

| pre | CA4P 2 h | % reduction | pre | CA4P 2 h | % reduction | |

| 1 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.49 ± 0.08* | 34 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 12 |

| 2 | 1.65 ± 0.09 | 0.48 ± 0.09* | 71 | 1.17 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.04* | 41 |

| 3 | 1.42 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.07* | 79 | 1.07 ± 0.03 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 28 |

|

| ||||||

| mean | 1.27 ± 0.27 | 0.42 ± 0.06** | 67 ± 14 | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 27 ± 8 |

IAUC60: Initial area under signal-time curve of first 60 s;

p < 0.05,

p< 0.001 from pretreatment.

Discussion

Following administration of the vascular targeting agent CA4P, BLI showed significantly decreased and delayed signal in the human mammary MDA-MB-231 carcinoma. We interpret this finding as due to induced vascular shutdown. Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI confirmed decreased tumor perfusion, which was further confirmed by histology. Both BLI and MRI are non-invasive and depict the same physiological effects, but BLI is much cheaper and offers a high throughput method for evaluating novel drugs and drug combinations and scheduling.

Bioluminescent imaging is a very sensitive technique revealing transfected cells at even sub-palpable volumes. Signal is attenuated at depth, but the technique can be applied routinely in both SC models and for monitoring orthotopic tumor development (3–8, 12). Several groups have shown robust correlations between detected light and tumor volume assessed by calipers or MRI (5, 12, 38, 39). In our early work we found strong correlations (r>0.8) between peak light signal, initial area under the curve, or signal intensity at 10 minutes post luciferin infusion and tumor volume following IP administration of 150 mg/kg D-luciferin (12). However individual measurements showed discrepancies and consecutive observations could vary by as much as 60%. Overall estimates at 95% confidence intervals suggested error < 20%. We later established better reproducibility based on 450 mg/kg luciferin administered SC. It is important to note that light-emission kinetics depend on tumor location: thus, for HeLa-luc cells growing subcutaneously we found maximum light-emission around 10 (median) and 12.7 (mean) minutes following IP administration, whereas in the current study using subcutaneous mammary tumors and subcutaneous administration of luciferin maximum light-emission occurred after about 7.5 minutes. In the current study BLI repeated two hours after saline injection showed light-emission kinetics highly consistent with baseline in terms of maximum light-emission, time to maximum light-emission, integrated light, and signal observed at seven minutes (Table 1, Figure 1). In five mice BLI measurements were again repeated 24 hours later and light-emission remained highly consistent (not significantly different from baseline or two hour time points). Two hours after CA4P administration light-emission kinetics were significantly altered with both delayed emission and reduced light intensity (Table 1). Light-emission kinetics remained low 24 hours later, when luciferin was readministered to a subgroup of mice.

Changes in vascular perfusion were confirmed by histology. These tumors show extensive vasculature as revealed by anti-CD 31 staining, which is also extensively perfused (Figure 3). Two hours after CA4P administration vasculature was detectable, but now there was no evidence of perfusion.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI has been applied previously both in animal models and the clinic to many tumor types with respect to Combretastatin administration (24, 30, 32). The changes observed here (Figure 4, Table 2) are consistent with previous observations (23, 30). Initial area under the curve reflects tumor blood flow, vascular permeability and the involved fraction of interstitial space. For the initial control study the signal enhancement was generally considerably greater in tumor than contra lateral thigh muscle (Table 2, Figure 4f). Following Combretastatin administration the IAUC decreased significantly in each tumor with a mean of about 70% in tumors (Table 2), but was not significantly changed in two of three muscles. One mouse did show decreased perfusion of normal muscle after Combretastatin, as also reported previously by Tozer et al. in rats (23).

Bioluminescent imaging is more traditionally used to assess tumor growth and metastatic spread rather than physiological effects. BLI enables detection of sub-palpable volumes and deep seated tumors in mice although this capability has not been exploited in the current study. Bioluminescent imaging is noninvasive, but does require administration of luciferin substrate. Thus, sampling tumor vasculature is only achieved at discrete time points following administration of the substrate. The requirement for a reporter substrate is common to other methods of interrogation also such as DCE MRI or DCE CT, which require administration of paramagnetic or radio opaque contrast agents (24, 30, 32, 34). Radionuclide approaches can be applied similarly (31), although they are more often used with autoradiography post mortem. Measurements based on Laser Doppler flowmetry (35), pressure probes (35) and NIR (36) may allow continuous sampling. Oximetry based on 19F MRI of hexafluorobenzene allowed essentially continuous mapping of pO2 changes with a 6½ minute time resolution (30).

One disadvantage of the BLI approach to assessing tumor vasculature is the need for luciferase expressing cells. However, numerous cell lines are now widely available and effective stable transfection is readily achievable though clonal selection could lead to differences between luciferase-expressing and parental tumor lines.

While Combretastatin (or Zybrestat) is now in Phase II/III clinical trials for anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) studies will continue to be required in preclinical settings to optimize combinations with other chemotherapeutic drugs or radiation in diverse tumor types. We believe BLI provides an optimal approach for examining acute pharmacodynamics together with the potential for long term chronic assessment of tumor control or growth. This approach could be equally applicable to other VTAs, which cause significant acute changes in blood flow, e.g., ZD6126, or 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) (19).

There is increasing realization that drugs may behave differently with various tumor types and sites of implantation. The observations here are consistent with a previous report in the same tumor type, which showed extensive central necrosis 24 hours after Combretastatin administration, while leaving a viable peripheral rim (20). BLI will facilitate effective screening of many tumor types implanted subcutaneously or orthotopically and with respect to monotherapy all combinations. We believe this is the first report of the use of BLI to monitor acute effects of a drug on tumor vasculature and represents an additional application of this new technology.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by DOD Breast Cancer Initiative IDEA Awards (DAMD-170310363 (DZ) and W81XWH-04-1-0551 (PPA)), the NCI Cancer Imaging Program pre-ICMIC CA86354 and U24 CA126608, and Simmons Cancer Center. NMR experiments were performed at the AIRC, an NIH BTRP # P41-RR02584. Combretastatin A4 phosphate was a gift of OxiGene.

We are grateful to Dr. Jerry Shay for providing luciferase expressing tumor cells and Drs. Li Liu and Ya Ren for generating the tumors. Allen Harper and Angelina Contero performed the bioluminescent imaging.

References

- 1.Li JZ, Holman D, Li HW, Liu AH, Beres B, Hankins GR, Helm GA. Long-term tracing of adenoviral expression in rat and rabbit using luciferase imaging. J Gene Med. 2005;7:792–802. doi: 10.1002/jgm.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice BW, Cable MD, Nelson MB. In vivo imaging of light-emitting probes. J Biomed Optics. 2001;6:432–440. doi: 10.1117/1.1413210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorne SH, Contag CH. Using in vivo bioluminescence imaging to shed light on cancer biology. Proc IEEE. 2005;93:750–762. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins DE, Yu SF, Hornig YS, Purchio T, Contag PR. In vivo monitoring of tumor relapse and metastasis using bioluminescent PC-3M-luc-C6 cells in murine models of human prostate cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:745–756. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006817.25962.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szentirmai O, Baker CH, Lin N, Szucs S, Takahashi M, Kiryu S, Kung AL, Mulligan RC, Carter BS. Noninvasive bioluminescence imaging of luciferase expressing intracranial U87 xenografts: correlation with magnetic resonance imaging determined tumor volume and longitudinal use in assessing tumor growth and antiangiogenic treatment effect. Neurosurg. 2006;58:365–372. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000195114.24819.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dikmen ZG, Gellert GC, Jackson S, Gryaznov S, Tressler R, Dogan P, Wright WE, Shay JW. In vivo Inhibition of Lung Cancer by GRN163L: A Novel Human Telomerase Inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7866–7873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu AR, Cai WB, Veeravagu A, Mohamedali KA, Chen K, Kim S, Vogel H, Hou LC, Tse V, Rosenblum MG, Chen XY. Multimodality molecular imaging of glioblastoma growth inhibition with vasculature-targeting fusion toxin VEGF(121)/rGel. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:445–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mi J, Sarraf-Yazdi S, Zhang X, Cao Y, Dewhirst MW, Kontos CD, Li C-Y, Clary BM. A Comparison of Antiangiogenic Therapies for the Prevention of Liver Metastases. J Surg Res. 2006;131:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehemtulla A, Stegman LD, Cardozo SJ, Gupta S, Hall DE, Contag CH, Ross BD. Rapid and quantitative assessment of cancer treatment response using in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Neoplasia. 2000;2:491–495. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verneris MR, Arshi A, Edinger M, Kornacker M, Natkunam Y, Karami M, Cao YA, Marina N, Contag CH, Negrin RS. Low levels of Her2/neu expressed by Ewing’s family tumor cell lines can redirect cytokine-induced killer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4561–4570. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bollinger RA. Vol PhD. UT Southwestern; Dallas: 2006. Evaluation of the Light Emission Kinetics in Luciferin/Luciferase-Based In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging for Guidance in the Development of Small Animal Imaging Study Design. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paroo Z, Bollinger RA, Braasch DA, Richer E, Corey DR, Antich PP, Mason RP. Validating bioluminescence imaging as a high-throughput, quantitative modality for assessing tumor burden. Molecular Imaging. 2004;3:117–124. doi: 10.1162/15353500200403172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contag CH, Ross BD. It’s not just about anatomy: In vivo bioluminescence imaging as an eyepiece into biology. JMRI. 2002;16:378–387. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipshutz GS, Gruber CA, Cao Y, Hardy J, Contag CH, Gaensler KM. In utero delivery of adeno-associated viral vectors: intraperitoneal gene transfer produces long-term expression. Mol Ther. 2001;3:284–292. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folkman J. Angiogenesis and apoptosis. Sem Cancer Biol. 2003;13:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denekamp J. Vascular attack as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990;9:267–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00046365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horsman MR, Siemann DW. Pathophysiologic effects of vascular-targeting agents and the implications for combination with conventional therapies. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11520–11539. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siemann DW, Bibby MC, Dark GG, Dicker AP, Eskens FA, Horsman MR, Marme D, Lorusso PM. Differentiation and definition of vascular-targeted therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorpe PE. Vascular Targeting Agents as Cancer Therapeutics. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10:415–427. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0642-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dark GG, Hill SA, Prise VE, Tozer GM, Pettit GR, Chaplin DJ. Combretastatin A-4, an agent that displays potent and selective toxicity toward tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1829–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kragh M, Quistorff B, Horsman MR, Kristjansen PE. Acute effects of vascular modifying agents in solid tumors assessed by noninvasive laser Doppler flowmetry and near infrared spectroscopy. Neoplasia (New York) 2002;4:263–267. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goertz DE, Yu JL, Kerbel RS, Burns PN, Foster FS. High-frequency Doppler ultrasound monitors the effects of antivascular therapy on tumor blood flow. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6371–6375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tozer GM, Prise VE, Wilson J, Locke RJ, Vojnovic B, Stratford MR, Dennis MF, Chaplin DJ. Combretastatin A-4 phosphate as a tumor vascular-targeting agent: early effects in tumors and normal tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1626–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galbraith SM, Maxwell RJ, Lodge MA, Tozer GM, Wilson J, Taylor NJ, Stirling JJ, Sena L, Padhani AR, Rustin GJS. Combretastatin A4 phosphate has tumor antivascular activity in rat and man as demonstrated by dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2831–2842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rustin GJ, Galbraith SM, Anderson H, Stratford M, Folkes LK, Sena L, Gumbrell L, Price PM. Phase I clinical trial of weekly combretastatin A4 phosphate: clinical and pharmacokinetic results. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2815–2822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson SP, McIntyre DJ, Checkley D, Tessier JJ, Howe FA, Griffiths JR, Ashton SE, Ryan AJ, Blakey DC, Waterton JC. Tumour dose response to the antivascular agent ZD6126 assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1592–1597. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prise VE, Honess DJ, Stratford MRL, Wilson J, Tozer GM. The vascular response of tumor and normal tissues in the rat to the vascular targeting agent, combretastatin A-4-phosphate, at clinically relevant doses. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:717–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padhani AR. MRI for assessing antivascular cancer treatments. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:S60–S80. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15334380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIntyre DJO, Robinson SP, Howe FA, Griffiths JR, Ryan AJ, Blakey DC, Peers IS, Waterton JC. Single dose of the antivascular agent, ZD6126 (N-acetylcoichinol-O-phosphate), reduces perfusion for at least 96 hours in the GH3 prolactinoma rat tumor model. Neoplasia. 2004;6:150–157. doi: 10.1593/neo.03247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao D, Jiang L, Hahn EW, Mason RP. Tumor physiological response to combretastatin A4 phosphate assessed by MRI. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:872–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson HL, Yap JT, Miller MP, Robbins A, Jones T, Price PM. Assessment of pharmacodynamic vascular response in a phase I trial of combretastatin A4 phosphate. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2823–2830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maxwell RJ, Wilson J, Prise VE, Vojnovic B, Rustin GJ, Lodge MA, Tozer GM. Evaluation of the anti-vascular effects of combretastatin in rodent tumours by dynamic contrast enhanced MRI. NMR in Biomed. 2002;15:89–98. doi: 10.1002/nbm.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beauregard DA, Pedley RB, Hill SA, Brindle KM. Differential sensitivity of two adenocarcinoma xenografts to the anti-vascular drugs combretastatin A4 phosphate and 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid, assessed using MRI and MRS. NMR in Biomed. 2002;15:99–105. doi: 10.1002/nbm.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng Q-S, Goh V, Carnell D, Meer K, Padhani AR, Saunders MI, Hoskin PJ. Tumor Antivascular Effects of Radiotherapy Combined with Combretastatin A4 Phosphate in Human Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:1375–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ley CD, Horsman MR, Kristjansen PEG. Early effects of combretastatin-A4 disodium phosphate on tumor perfusion and interstitial fluid pressure. Neoplasia. 2007;9:108–112. doi: 10.1593/neo.06733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JG, Liu H, Zhao D, Mason RP. Acute effects of combretastatin A4 phosphate on breast tumor hemodynamics monitored by near infrared spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Topical Meeting; Fort Lauderdale, Fl. 2006. pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tozer GM, Prise VE, Wilson J, Cemazar M, Shan SQ, Dewhirst MW, Barber PR, Vojnovic B, Chaplin DJ. Mechanisms associated with tumor vascular shut-down induced by combretastatin A-4 phosphate: Intravital microscopy and measurement of vascular permeability. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6413–6422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Sun ZD, Peng JC, Zhan LS. Bioluminescent imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma in live mice. Biotechnol Letters. 2007;29:1665–1670. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen CC, Hwang JJ, Ting G, Tseng YL, Wang SJ, Whang-Peng J. Monitoring and quantitative assessment of tumor burden using in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 2007;571:437–441. [Google Scholar]