Abstract

Migration of leukocytes into a site of inflammation involves several steps mediated by various families of adhesion molecules. CD99 play a significant role in transendothelial migration (TEM) of leukocytes. Inhibition of TEM by specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) can provide a potent therapeutic approach to treating inflammatory conditions. However, the therapeutic utilization of whole IgG can lead to an inappropriate activation of Fc receptor-expressing cells inducing serious adverse side effects due to cytokine release. In this regard, specific recombinant antibody in single chain variable fragments (scFvs) originated by phage library may offer a solution by affecting TEM function in a safe clinical context. However, this consideration requires large scale production of functional scFv antibodies under GMP conditions and hence, the absence of toxic reagents utilized for the solubilization and refolding steps of inclusion bodies that may discourage industrial application of these antibody fragments. In order to apply the scFv anti-CD99 named C7A in a clinical setting we herein describe an efficient and large scale production of the antibody fragments expressed in E.coli as insoluble protein avoiding gel filtration chromatography approach, and laborious refolding step pre- and post-purification. Using differential salt elution which is a simple, reproducible and effective procedure we are able to separate scFv in monomer format from aggregates. The purified scFv antibody C7A exhibits inhibitory activity comparable to an antagonistic conventional mAb, thus providing an excellent agent for blocking CD99 signalling. Thanks to the original purification protocol that can be extended to other scFvs that are expressed as inclusion bodies in bacterial systems, the scFv anti-CD99 C7A herein described represents the first step towards the construction of new antibody therapeutic.

Keywords: Single chain variable fragment (scFv), Purification, Aggregates, inclusion body, blocking monocyte transmigration

1. Introduction

CD99 is a relatively unique molecule unrelated to any other molecule in the human genome except the closely-related paralog CD99-like 2 (CD99L2), which may have arisen from a common ancestral gene (Suh et al., 2003). The gene encoding CD99 is in the pseudo autosomal region of the human X chromosome (Smith et al., 1993). In mice, the region of the genome syntenic to the pseudoautosomal region of the human X chromosome is on chromosome 4 (Park et al., 2005) where the gene encoding for mouse CD99 determinant is located. CD99 is a type 1 transmembrane exclusively O-linked glycoprotein that in humans has an apparent molecular weight of 32 kDa on SDS-PAGE. Almost half the apparent molecular weight is due to carbohydrate modification (Schenkel et al., 2002). CD99 is expressed along the cell borders between endothelial cells. It is also expressed diffusely on the surfaces of most circulating blood cells, although the degree of expression varies considerably between subtypes of leukocytes and expression is lower than on endothelial cells. CD99 is also expressed on various tumors including Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor (Schenkel et al., 2002). CD99 can act as an adhesion molecule, and L cells transfected with CD99 aggregate in a homophilic manner, with CD99 on once cell binding to CD99 on the adherent cell (Schenkel et al., 2002). Homophilic interaction between CD99 on adjacent endothelial cells may help stabilize endothelial borders, but CD99 is not a part of the adherent junction complex. CD99 does, however, play a significant role in TEM of leukocytes. Similar to regulation of TEM by platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1), homophilic interaction between CD99 at the endothelial cell border and CD99 on monocytes (Schenkel et al., 2002) and neutrophils (Lou et al., 2007) is required for transmigration. However, CD99 regulates a later step in transmigration than PECAM1. Leukocytes in which PECAM1 has been blocked by mAb can still be prevented from transmigrating if anti- CD99 mAb (hec2) is added after the anti-PECAM-1 block has been removed. Conversely, if CD99 interaction is first blocked, leukocytes can no longer be inhibited from transmigrating by anti-PECAM-1 antibody when the anti-CD99 block is removed (Schenkel et al., 2002). In support of this, confocal images of leukocytes blocked in the act of transmigration by anti-CD99 show their leading edge under the endothelial cytoplasm, their cell body lodged at the border between endothelial cells, and the trailing uropod on the apical surface (Schenkel et al., 2002; Lou et al., 2007). As long as the block continues, they migrate along the junctions over the surface of the endothelium in this manner, unable to finish transmigration. Blocking antibodies against mouse CD99 inhibit inflammation in several animal models. Migration of T lymphocytes into skin (Bixel et al., 2007) and neutrophils and monocytes into the peritoneal cavity (Dufour et al., 2008) are blocked by interfering with CD99 function. Hence, the inhibition of TEM mediated by specific human mAb represents a potent and safe immunotherapeutic approach to treating inflammatory condition. Monoclonal antibody therapy is the fastest growing sector of pharmaceutical biotechnology and a number of antibody-based biopharmaceuticals have been approved for different human pathologies including several inflammatory and immune diseases (Kotsovilis and Andreakos 2014).Several factors determine the efficacy of these products, including target specificity, effector functions and xenogeneic origin of monoclonal immunoglobulin that alter the pharmacokinetic profile of the antibody, leading to severe toxicity and preventing repeat dosing (Mirick et al., 2004) responses to monoclonal antibodies. Today, with the advances of recombinant genetic strategies rodent antibodies have been genetically modified in chimeric and humanized versions, significantly reducing their immunogenicity (Presta 2005). However, the main pitfalls of the use of conventional mAbs (usually IgG) is not only related to their immunogenicity but also to other biochemical and biological aspects such as slow rates of clearance that may affect the physiology of normal tissues and inappropriate activation of Fc receptor expressing cells that can lead to massive cytokine release which could be associated to severe side effects. In this context, the ability to produce fully human antibody fragments has represented a significant breakthrough in the field of antibody engineering. Antibody fragments in particular in scFv format with their small size (27-32 kDa), display better tissue penetration compared to full length monoclonal antibodies without any significant toxicity. ScFvs represent the smallest stable antibody fragments still capable of specifically binding an antigen. They are structured as a single polypeptide chain incorporating a heavy chain variable (VH) and a light chain variable (VL) region of an antibody, linked by a flexible linker. The extremely versatile format of scFvs can be tailored by genetic engineering to improve affinity and stability. They can be modified in their size, pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, specificity, valency and effectors functions (Hudson and Souriau 2003). Moreover, scFvs can be easily expressed and produced in E. coli in large quantity (Kipriyanov and Little 1999) However, the expression of heterologous proteins in E. coli often encounters the formation of inclusion bodies, which are insoluble and nonfunctional protein aggregates. For the successful production of antibody fragments from inclusion bodies, a refolding step is required for solubilization and functional recovery of the protein (Gautam et al., 2012). However, these procedures represent complex biochemical approaches, thus discouraging industrial production. Therefore a simple and effective method is required for biological and medical utilization of scFv antibodies. In this context, herein we describe an efficient and simple procedure for large scale production of scFvs in E. coli system from inclusion bodies. Furthermore, related methodologies to obtain monomeric soluble biologically active scFv are in detail described. ScFvs were purified with a His6-tag using immobilized metal affinity and anion chromatography avoiding gel filtration chromatography approach, and laborious refolding step pre and post purification phase. Biological assays show that the anti-CD99 scFv C7A subjected to this procedure is fully active for specific binding and blocking activity of TEM.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Cloning

scFv anti-CD99 isolated from the ETH-2 human scFv displayed phage library (Viti et al., 2000) by bio-panning approach and affinity maturing as previously described (Neri et al., 1996). scFv anti-CD99 was cloned into a pET22b (+) vector (Novagen, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) by amplifying the sequence from pDN332 including the D3SD3-FLAG-His6 tag at the C-terminus. For cloning in pET22b (+) the scFv sequence was amplified using the primers NcoI Fw 5’- CCAGCCGGCCATGGCCGAGGTG–3’and EcoRI Rev:5’- ACAACTTTCAACAGTCTAATGGTGATGGTG-3’. Amplicons were digested together with pET22b (+) vector, with NcoI and EcoRI enzymes (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) at 37°C for 3 hours. The digested products were purified and ligated together with T4 DNA ligase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 4°C overnight. The ligation mix was transformed into E.coli strain BL21(DE3) ((F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3)) for protein expression. Positive clones were screened for correct insertion by colony polymerase chain reaction and sequencing.

2.2 Expression

E. coli BL21 (DE3) starter culture grown to an O.D.600 of 2.0 in a shaking incubator set at 37°C and 200 rpm was inoculated for large scale production into 20L Bioreactor (Biostat C, Sartorius). The fermentation phase was carried out according to Moricoli et al. (2014). After three hours induction, the cell culture was harvested by centrifugation (Beckman Coulter) at 5000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C.

2.3 Cell lysis and solubilization of inclusion bodies

Collected cells were suspended in 7L lysis buffer containing: 20mM Imidazole, 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, disrupted using a homogenizer (GEA Niro Soavi) at 680 bar and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 60 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 7L of solubilization buffer containing: 8M Urea, 20mM Imidazole, 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 and incubated for 16 hours under agitation at 21°C and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 60 minutes at 4°C. Finally the supernatant was filtered using 0.45μm sterilizing filter (Merck Millipore).

2.4 Purification

Purification was performed on an AKTA explorer 100 (GE-Healthcare) and BPG 100/500 column (GE-Healthcare). All packed chromatography columns were cleaned and depyrogenated by flowing 1M NaOH through the column at 40ml/min for 2 hours and washed with water for injection (WFI) until the pH of the column effluent was < pH 8. The first step consisted of an IMAC Chelating Sepharose fast flow (GE Healthcare) a Ni-chelating column charged with 0.1M NiSO4. The column was equilibrated with a buffer containing 8M Urea, 20mM Imidazole, 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 (buffer A). After sample loading and a washing step with equilibration buffer, a linear gradient from 8M to 0M of Urea equivalent to three column volumes (CV) was used to eliminate Urea. The gradient was applied by using buffer A and buffer A without urea. The column was washed with 70mM Imidazole in 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. scFv anti-CD99 was eluted in a single peak with 250mM Imidazole in 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. A further DEAE Sepharose fast flow (GE Healthcare) column using differential salt elution was used to separate monomer scFv from scFv anti-CD99 aggregates. The column was equilibrated with 50mM NaCl in 1.5mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. The IMAC eluate pool was diluted tenfold with 1.5mM EDTA 10% (v/v) glycerol, 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, and applied to the column. After washing with equilibration buffer, bound scFv was eluted with 0.25M NaCl in 1.5mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 and collected in a single peak based on 280nm absorbance. scFv aggregates were eluted with 0.5M NaCl in 1.5mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, then collected in a single peak based on 280nm absorbance. Finally the monomer scFv anti-CD99 eluted with 0.25M NaCl was filtered using a Chromasorb 50ml device (Merck Millipore) for endotoxin reduction and then filtered using a 0.22μm sterilizing filter (Merck Millipore).

2.5 Protein concentration

Total protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay, a method based on the Bradford assay (Zor and Selinger 1996), using BSA as a standard. Colour development and absorbance values were measured using a Spectophotometer Shimadzu UV-1601 and compared to standard curvers.

2.6 SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting analysis

Sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under reduced conditions was carried out according to (Laemmli 1970) The samples were run on 12% gels at 100V for 90 min using BioRad mini protein system (BioRad Laboratories). The resolved protein samples were visualized by staining with Comassie brilliant blue. Western Blotting (WB) analysis samples were separated by SDS-PAGE at 12% (w/v) and transferred overnight at +4 °C on nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare) (Towbin et al., 1979) Membranes were saturated with Tris buffer saline (TBS) containing 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated for three hours at + 4°C with an anti-polyhystidine monoclonal antibody (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) 1:1,000 diluted in TBS containing Tween 0.05% (w/v) (TTBS) with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk. After incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugated (BioRad) for one hour at room temperature the immuno reactive bands were revealed by the ECL detection system (GE Healthcare). Images derive from SDS-PAGE and WB collected and analyzed by a Chemi Doc XRS (BioRad).

2.7 Gel Filtration chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was used to evaluate the structure of the scFvs. SEC was performed with AKTA Explorer 100 using a Hi-load Superdex 75 16/60 (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated with PBS (phosphate buffer saline) pH 7.5, at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. 2 ml of purified recombinant antibodies was applied to the column. scFvs were detected by its absorbance at 280nm. The molecular weights were estimated based on standard curve calibrating the system with proteins of known molecular weight: Albumin 67,000 Da, Ovalbumin 45,000 Da, Carbonic Anhydrase 30,000 Da, Trypsin Inhibitor 20,100 Da and Thiamine 3337,27 Da. The void volume (Vo) was determined using Blue Dextran 2000. The log molecular mass of each standard was plotted against the fraction of the stationary gel volume available for diffusion (Kav) to generate a calibration curve. The proportion of monomer to the total was determined by Unicorn software (GE Healthcare) by integration of the relative area under the chromatographic profile corresponding to each peak.

2.8 Endotoxin content

Bacterial endotoxin levels were determined with the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) kit (PBI International) in the purified scFv anti-CD99 preparation following the instruction manual.

2.9 Production of the recombinant human CD99 antigen fragment (rCD99) for Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA)

E. Coli TG1 cells transformed with recombinant plasmids pQE30a-CD99/His (Gellini et al. 2012) were grown in a fermentation process at 37°C in 5L of vegetable peptone broth (VPB): vegetable peptone 18g/L, yeast extract 3g/L, potassium phosphate dibasic 2.5g/L, sodium chloride 5g/L, dextrose 2.5g/L, containing 100μg/mL ampicillin, until the optical density (OD) at 600nm was 0.6. Induction of the rCD99 fragment was obtained by adding 1mM IPTG. Induced cultures were then incubated for a further 3 hours at 37°C. Finally, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. For protein purification, the pellets were resuspended in 50 ml/L of a buffer containing 20 mM phosphate buffer, 1.5mM EDTA, pH 7.5, and homogenized at 680 Bar. The cell lysis solutions were centrifuged at 8000 trpm for 60 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant filtered through 0.45μm filter (Merck Millipore). Purification was performed by using AKTA explorer chromatography system (GE Helthcare). The first step consisted of an IMAC Chelating Sepharose fast flow (GE Healthcare) a Ni-chelating column charged with 0.1M NiSO4. The column was equilibrated with a buffer containing 20mM Imidazole, 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. After sample loading and a washing step with equilibration buffer, the column was washed with 50mM Imidazole in 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. rCD99 fragment was eluted in a single peak with 250mM Imidazole in 500mM NaCl and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. The IMAC eluate pool was diluted tenfold with 1.5mM EDTA 10% (v/v) glycerol, 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, and applied to the anionic exchange DEAE column. After washing with equilibration buffer, bound rCD99 was eluted with 0.2M NaCl in 1.5mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 20mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 and collected in a single peak based on 280nm absorbance. The purified protein was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter (Merck Millipore) and collected at –80°C.

2.10 ELISA assay

2HB 96-well plates (M-Medical) were coated with 100 μl/well of rCD99 antigen 1μg/ml diluted in PBS (100μl/well) and kept at 37°C for 16-18 hours. After five washes in PBS containing Tween-20 0.05% v/v (TPBS), the plate was blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA) 1% (w/v) in PBS (PBSB) (150μl/well) and kept for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing in TPBS scFvs were diluted in PBS and 2% (w/v) not fat dry milk (PBSM). They were tested (100μl/well) at different concentrations and the plate was incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C. Thereafter the plate was incubated with a freshly prepared mixture containing an anti-His6 monoclonal antibody (Serotec) pre-diluted 1:400 (v/v) in PBSM (100μl/well) and kept for 1 hour at 37°C. The immuno-reactive signals were highlighted after further addition of a goat anti mouse HRP-conjugated antibody (BioRad) 1:1,000 (v/v) diluted in PBSM (100μl/well) with ABTS (Roche Diagnostic) as substrate. The absorbance values were obtained reading at 405nm with microplate reader 45 minutes after the addition of the staining solution (BioRad).

2.11 Cell Culture

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected and isolated from blood of healthy human volunteers, diluted to 4 × 106 PBMC/ml in Medium 199 plus 0.1% human serum albumin as described by Muller and Weigl (1992). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were cultured from umbilical cords obtained from healthy women after normal delivery. Cells at passage two were plated onto hydrated collagen gels made in 96-well culture dishes as described by Muller and Weigl (1992)

2.12 Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, NJ All USA). PBMC staining and washing steps were conducted in PBS without divalent cations plus 1% heat-inactivated FBS, Cells were lifted with trypsin-EDTA and stained with mouse anti-His6 monoclonal antibody (Serotec) pre-diluted 1:400 (v/v). Finally cells was incubated with a goat anti-mouse FITC conjugated antibody (Sigma Aldrich) diluted 1:250 (v/v)

2.13 Transendothelial Migration (TEM) assay

Monolayers of human umbilical vein endothelial cells grown on hydrated collagen gels made in 96-well culture dishes were used within three days of achieving confluence. As soon as the PBMC were isolated, aliquots were mixed with an equal volume of control antibody(mAb hec1, recognizes VE-cadherin but does not block TEM), anti-CD99 mAb hec2 (Schenkel et al., 2002; Lou et al., 2007), or CD99 scFv C7A also in Medium 199 plus 0.1% human serum albumin so that the final concentration of PBMC was 2 × 106/ml. The endothelial monolayers were washed twice with warm Medium 199 and then 100 μl of PBMC suspension was added to each well of replicate monolayers of endothelial cells. The co-cultures were returned to the CO2 incubator for 60 minutes. Then the monolayers were washed sequentially with 100 μM EGTA in PBS then warm PBS with calcium and magnesium. They were then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight then stained and evaluated for transmigration as described by Muller et al. (1993) Briefly, after staining the fixed monolayers with modified Wright-Giemsa stain, co-cultures were removed from the individual wells, mounted on slides and examined by Nomarski optics at 600X. Monocytes in focus above the level of the endothelial cell were counted as adherent but not transmigrated. Monocytes in focus below the level of the endothelial cell (i.e. in the collagen gel) were counted as transmigrated. The percent transmigration was calculated as the number of transmigrated cells divided by the sum of the transmigrated plus adherent cells.

3. Results

3.1 Expression of scFv C7A

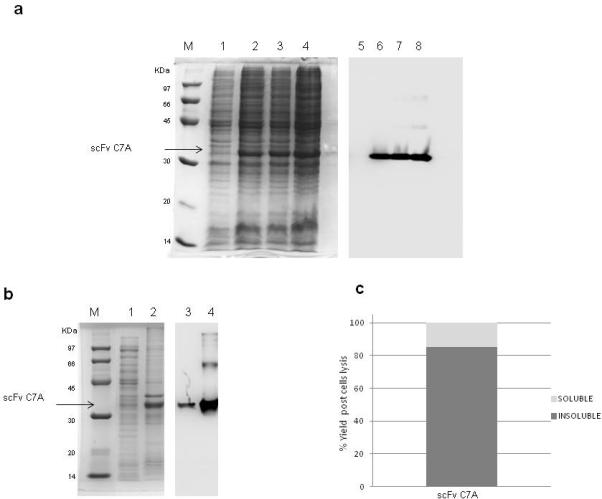

Sequencing of the expression construct revealed that the scFv anti-CD99 C7A is in VH-linker-VL format with the 15 amino acid (Gly4Ser) 3 linker residues. Protein expression was induced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain transformed with pET22b-scFv C7A construct. It was induced at 10 O.D by adding 1mM IPTG for 3h at 37°C. In this condition the yield of scFv was approximately 35mg/L. The SDS-PAGE analysis showed a major band corresponding to the expected molecular mass (33kDa) of scFv C7A (Fig.1a) the target protein was further subjected to western blotting (WB) to confirm the expression of recombinant scFv (Fig.1a). The Fig. 1b shows SDS-PAGE and WB of the soluble and insoluble quantity of scFv obtained after cell lysis and solubilisation of inclusion bodies. The Fig.1c showed that the highest percentage of scFv (75%) is included in the insoluble fraction. Therefore was decided to purify scFv starting from inclusion bodies.

Fig.1.

Panel (a) shows SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting (WB) analysis of scFv C7A expression with 1mM IPTG added at 37°C. Low molecular weight marker (lane M), non induced culture (10μg) (lane 1) and induced culture after one, two and three hours are shown in lane 2 through 4 (10μg for each lane). The expression of scFv C7A was confirmed by an anti Histag antibody in WB analysis (lane 5-8) (10μg for each lane). Panel (b) shows SDS-PAGE analysis of the soluble (lane 1) (10μl) and insoluble quantity (lane 2) (10μl) of scFv C7A obtained after cell lysis and solubilisation of inclusion bodies confirmed by an anti His-tag antibody in WB analysis (lane 3 and lane 4) (10μl for each lane); low molecular weight marker (lane M). Panel (c): Histogram of scFv relative quantity present in the soluble and insoluble fraction analysed by Chemi Doc XRS (BioRad) and calculated by Quantity one software (BioRad).

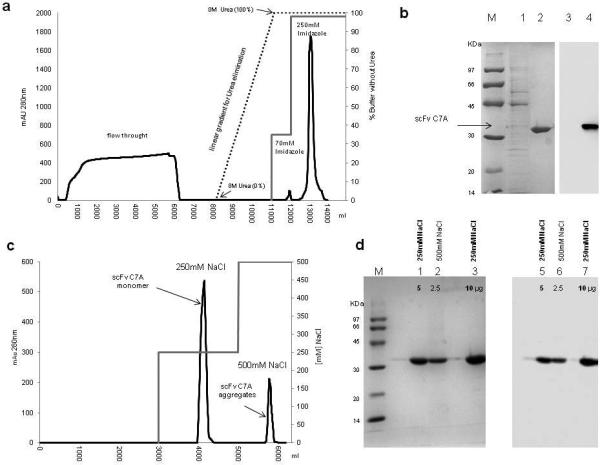

3.2 Purification and biophysical analysis of scFv C7A

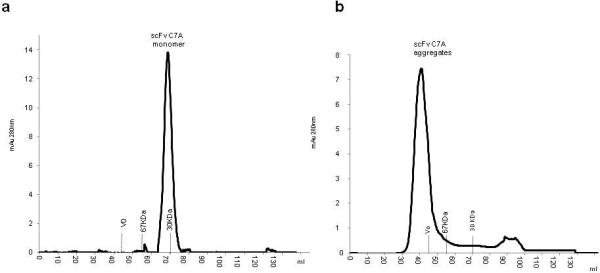

After the solubilisation of the inclusion bodies by 8M Urea buffer, the supernatant was loaded onto an IMAC nickel column, which binds scFv C7A via the histidine tag. In this step the column was equilibrated in the presence of 8M Urea. Subsequently a linear gradient (3CV) for in column Urea elimination was used (from 8M Urea to 0M). A washing step by 70mM Imidazole was used for removing the residual high and low molecular weight contaminant host protein in the scFv sample. Elution by 250mM Imidazole was revealed scFv 95% purity as estimated by SDS-PAGE analysis loading 5μg/lane (Fig. 2a-b). The IMAC-eluate was diluted 1:10 and loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose column; this step allowed to separation of aggregates scFv C7A from monomer. The scFv monomer was eluted at 0.25M NaCl while aggregates were eluted at 0.5M NaCl (Fig.2c). SDS-PAGE analysis of the 0.25M NaCl eluate showed the presence of highly pure band of 33kDa which to corresponded to scFv C7A confirmed by WB analysis with 99% purity estimated on loading 10μg/lane. Peak eluted at 0.5M NaCl also showed the presence of pure band scFv anti-CD99 (Fig.2d) but gel filtration analysis clearly showed that scFv anti-C7A eluted at 0.25M NaCl consisted of a monomer forms (Fig.3a) while the scFv eluted at 0.5M NaCl consisted of aggregates forms (Fig.3b). Table 1 summarize the yield, the percentage of purity and the percentage of total scFv C7A monomer in the purification steps. The monomeric scFv at 0.25M NaCl was tested for endotoxin contamination before and after Chromasorb device endotoxin removal. The endotoxin derived from bacterial cell wall has a number of biological effects on mammalian cells it would interfere with bioactivity assays or to be inappropriate for therapeutically conditions for human use. The LAL assay indicated a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) concentration of about 1000EU/ml (1EU/μg) after anionic chromatography step. The chromasorb device reduced endotoxin content on the scFv to 1EU/ml (0,001EU/μg), which is well within a range that can be used for clinical use and for cell migration assays.

Fig.2.

Panel (a) shows the first purification step using IMAC Sepharose. The chromatogram shows the washing step with buffer containing 70mM Imidazole and scFv elution in a single peak with buffer containing 250mM Imidazole. Panel (b) the peaks were analyzed in SDS-PAGE. Low molecular weight marker (lane M); eluate 70mM imidazole (5μg) (lane 1) eluate 250mM imidazole (5μg) (lane 2). WB analysis with anti His-tag antibody confirms the efficient washing step devoid of the scFv (5μg). (lane 3) and the presence of scFv C7A eluate 250mM Imidazole (5μg) (lane 4). In panel (c) shows the final purification step using DEAE Sepharose. Chromatogram shows elution in two peaks at 0.25M and 0.5M NaCl. Panel (d) the protein profile of the two peaks was analyzed by SDS-PAGE: low molecular weight marker (lane M); eluate 0.25M NaCl (5μg) (lane 1); eluate 0.5M NaCl (2.5μg) (lane 2) eluate 0.25M NaCl (10μg) (lane 3).This is confirmed by WB analysis with anti His-tag antibody: eluate 0.25M NaCl (5μg) (lane 4); eluate 0.5M NaCl (2.5μg) (lane 5) eluate 0.25M NaCl (10μg) (lane 6).

Fig.3.

Panel (a) shows gel filtration of scFv C7A monomer eluted with 0.25M NaCl, the presence of aggregates is <1%. The peak integration was calculated with Unicorn software (GE Healthcare). Panel (b) shows gel filtration of scFv anti-C7A aggregates eluted with 0.5M NaCl that were eluted in proximity of the void volume (Vo).

Table 1.

Summary of scFv C7A purification

| Purification step | Yield (mg) | % purity by SDS-PAGE | % monomer by SEC | % overall yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant urea 8 M | 1200 | 68 | 45 | 100 |

| IMAC | 590 | 95 | 70 | 49 |

| DEAE | 500 | 99 | 99 | 42 |

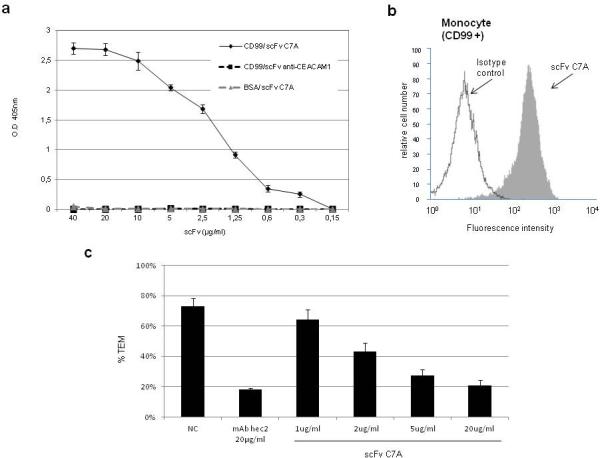

3.3 Biological characterization of scFv C7A

The binding properties of the purified antibody were tested in ELISA assays, where it manifested a very strong binding to purified extracellular fragment rCD99 (Fig.4a). In contrast no binding to rCD99 was observed with an irrelevant scFv subjected to the same procedure. No binding was detected either when the plates were coated with an unrelated protein e.g. BSA. The binding occurred in an ELISA plate as well as in the Western blotting denaturating gel system indicating that the scFv recognized its target site in rCD99 both as a folded sequence and as a linear epitope. Flow cytometry studies showed that scFv C7A binds the external domain of CD99 cell adhesion molecule expressed on human monocyte cell lines (Fig.4b). Staining of CD99 by mAb hec2 on freshly isolated monocyte resulted in similar staining profiles (data not shown). To further evaluate the biological activity of the scFv C7A, we performed a transendothelial migration monocyte blocking assay, utilized for previous antibody anti-CD99 blocking studies. (Schenkel et al., 2002; Lou et al., 2007) The results show that scFv C7A blocked monocyte transmigration in a concentration-dependent manner. A concentration of 20 μg/ml ScFv blocked transmigration by >70% . (Fig.4c) Interestingly, the monovalent scFv had about the same ability to block transmigration as bivalent mAb hec2 at the same concentration.

Fig.4.

Panel (a) Specific binding of scFv C7A to rCD99 analyzed by ELISA , no reactivity was determined to BSA. As negative control was used a scFv anti CEACAM1 to rCD99. Panel (b) shows the binding profile by flow cytometry of one representative experiment of three performed of scFv anti-CD99 samples to monocyte cells. Panel (c) shows TEM analysis: Negative control (NC) monocyte migration (70%) in the presence of non-blocking anti-VE-cadherin mAb; positive control with 20μg/ml of hec2 mAb confirms the ability of anti-CD99 to block transmigration. The different concentrations of scFv C7A (from 1 to 20μg/ml) shows the antibody fragment ability to blocking monocyte transmigration. At a concentration of 20μg/ml scFv C7A monovalent, TEM was 21% . Values are mean ± SEM of three experiments performed with six replicates in each experiment..P values vs. control for hec2 = 0.0003, for scFv 2 μg/ml = 0.008, for scFv 5 μg/ml = 0.0011, for scFv 20 μg/ml = 0.0006..

4. Discussion

Migration of monocytes from the bloodstream across vascular endothelium is required for entry into sites of inflammation. Transendothelial migration of monocytes (TEM) initially involves tethering of cells to the endothelium, followed by loose rolling along the vascular surface, firm adhesion to the endothelium and diapedesis between the tightly apposing endothelial cells. (Sullivan and Muller 2013) Diapedesis by monocytes occurs through interaction between PECAM-1 on both the monocyte and the endothelial cells, followed by similar homophilic adhesion via CD99. After penetration of the endothelial basement membrane, monocytes migrate through the extracellular matrix of the tissues where they may migrate to sites of inflammation. (Muller 2013). Several publications show clearly that the blocking antibodies against CD99 inhibit inflammation in in vitro and in vivo models. (Bixel et al., 2010; Dufour et al., 2008;) These findings indicate that the transmembrane CD99 protein represents a valid pharmacological target for the treatment of inflammatory process. mAbs are an increasingly important class of therapeutic agents. Intact antibodies are bivalent specific target reagent with antigen binding site located on the two Fab tips and recruitment of effector functions mediated by the stem Fc domain. This last domain recruits cytotoxic effector functions through complement as well as by direct binding to Fc receptors on leukocytes. However there is a range of therapeutic applications in which the Fc-mediated effects are not required and are even detrimental. For example, with antibodies that work by reducing the ability of inflammatory cells to pass into inflamed tissue, an inappropriate activation of Fc receptor-expressing cells can lead to massive cytokine release and associated toxic effects. (Holliger and Hudson 2005). Recombinant DNA technologies have made possible the modification of an antibody into smaller binding fragments such as scFv, in which the antigen binding sites can be retained. scFvs are usually expressed as inclusion bodies in E.coli. Highly efficient purification and refolding methods are required to provide enough active proteins for therapeutic or diagnostic use. Several refolding systems from insoluble scFv have been reported i.e Gel Filtration chromatography, elaborate dialysis, or use reagent as ionic detergents. (Bu et al., 2013; Ong, et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2006). Unfortunately these biochemical processes are not suitable as a source of therapeutic antibodies. Hence there is an urgent need for an innovative process for large scale production of scFvs for preclinical and clinical use. In the present study, the a human anti-CD99 scFv C7A was constructed and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) star as inclusion bodies. A convenient procedure of two steps on-column purification and refolding was provided. Large scale production at 15L scale of scFv C7A with a total yield of 500mg (~35mg/L) render the process optimal for a high production yield of drug substances. For antibody purification and refolding procedure neither use of dialysis step or additives inappropriate for human use were required. The denaturated inclusion body samples were loaded directly on column. In the first chromatographic step an affinity His-tag allows the elimination on-column of Urea by the application a linear gradient step. At the same time a washing step by 70mM Imidazole buffer was able to eliminate most bacterial contaminants and to obtain a scFv at 95% purity. The second chromatographic step, anion exchange chromatography, separated the aggregates from monomeric active form and avoids the use of gel filtration chromatography in the final step. The principle is simple but very effective. The use of differential salt elution has allowed us to discriminate the monomeric forms of the scFv that have less negative charge compared to aggregated forms of scFvs with more negative charges and therefore a higher binding capacity towards of the positively charged DEAE resin. The eluted monomeric scFv C7A shows a 99% purity by SDS-PAGE and Gel filtration analysis. The endotoxin content was 1EU/ml (0,001EU/μg) by using the chromasorb salt tolerant device before final sterilization step, making the antibody suitable for cellular assays and for clinical application. The refolded scFv showed correct structure by analytical gel filtration and high binding affinity towards its cognate antigen CD99 in ELISA and flow-cytometry studies. Activity assay showed that the scFv C7A is able to block monocyte transendothelial migration with an activity level comparable to anti-CD99 mAb hec2 which was obtained from the eukaryotic expression system. In conclusion, by using the purification procedure herein reported and described, biologically active scFvs C7A were obtained. The materials and methods utilized allow a large scale production of a safet antibody which is appropriate for industrial requirements and clinical application. Furthermore, the simple and flexible structure of the scFvs makes it possible to design scFv C7A biochemical variants with an optimum balance between diffusion and retention in tissues, so indicating that the scFv C7A human antibody is a potential platform for developing a completely human anti-inflammatory biological agent. It may also be applicable to other scFvs or other recombinant proteins.

References

- Suh YH, Shin YK, Kook MC, Oh KI, Park WS, Kim SH, Lee IS, Park HJ, Huh TL, Park SH. Cloning, genomic organization, alternative transcripts and expression analysis of CD99L2, a novel paralog of human CD99, and identification of evolutionary conserved motifs. Gene. 2003;307:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Goodfellow PJ, Goodfellow PN. The genomic organisation of the human pseudoautosomal gene MIC2 and the detection of a related locus. Hum. Molec. Genet. 1993;2:417–22. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Shin YK, Suh YH, Park WS, Ban YL, Choi HS, Park HJ, Jung KC. Rapid divergency of rodent CD99 orthologs: implications for the evolution of the pseudoautosomal region. Gene. 2005;353:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel AR, Mamdouh Z, Chen X, Liebman RM, Muller WA. CD99 plays a major role in the migration of monocytes through endothelial junctions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:143–50. doi: 10.1038/ni749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou O, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Muller WA. CD99 is a key mediator of the transendothelial migration of neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2007;178:1136–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixel G, Kloep S, Butz S, Petri B, Engelhardt B, Vestweber D. Mouse CD99 participates in T cell recruitment into inflamed skin. Blood. 2004;104:3205–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour EM, Deroche A, Bae Y, Muller WA. CD99 Is Essential for Leukocyte Diapedesis In Vivo. Cell Commun Adhes. 2008;15:351–363. doi: 10.1080/15419060802442191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Weigl J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:819–828. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller WA, Weigl SA, Deng X, Phillips DM. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178:449–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert JM. Marketed therapeutic antibodies compendium. MAbs. 2012;4:413–415. doi: 10.4161/mabs.19931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo TT, Aveson VG. MAbs. 2011;3(5):422–430. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.5.16983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontermann RE. Review Alternative antibody formats. Curr Opin Mol Ther. Apr. 2010;12(2):176–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S, Dubey P, Rather GM, Gupta MN. Recent Pat Biotechnol. Non-chromatographic strategies for protein refolding. 2012 Apr;6(1):57–68. doi: 10.2174/187220812799789172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viti F, Nilsson F, Demartis S, Huber A, Neri D. Design and use of phage display libraries for the selection of antibodies and enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 2000;326:480–505. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)26071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri D, Petrul H, Winter G, Light Y, Marais R, Britton KE, Creighton AM. Radioactive labeling of recombinant antibody fragments by phosphorylation using human casein kinase II and [gamma-32P] -ATP. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996 Apr;14(4):485–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0496-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zor T, Selinger Z. Linearization of the Bradford protein assay increases its sensitivity: theoretical and experimental studies. Anal. Biochem. 1996;236:302–308. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of a structural protein during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1979;76(9):4350–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellini M, Ascione A, Flego M, Mallano A, Dupuis ML, Zamboni S, Terrinoni M, D'Alessio V, Manara MC, Scotlandi K, Picci P, Cianfriglia M. Generation of Human single-chain Antibody to the CD99 Cell Surface Determinant Specifically Recognizing Ewing's Sarcoma Tumor Cells. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012 Feb 15; doi: 10.2174/1389201011314040011. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou O, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Muller WA. CD99 is a key mediator of the transendothelial migration of neutrophils. J Immunol. 2007 Jan 15;178(2):1136–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixel MG, Li H, Petri B, Khandoga AG, Khandoga A, Zarbock A, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Wolburg H, Sorokin L, Zeuschner D, Maerz S, Butz S, Krombach F, Vestweber D. CD99 and CD99L2 act at the same site as, but independently of, PECAM-1 during leukocyte diapedesis. Blood. 2010 Aug 19;116(7):1172–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-256388. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-256388. Epub 2010 May 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Wang X, Yin C, Zhang Z, Lin Q, Zhen Y, Huang H. One-step on-column purification and refolding of a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibody against tumour necrosis factor alpha. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2006 Mar;43(Pt 3):137–45. doi: 10.1042/BA20050194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsovilis S, Andreakos E. Therapeutic human monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1060:37–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-586-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirick GR, Bradt BM, Denardo SJ, Denardo GL. A review of human anti-globulin antibody (HAGA, HAMA, HACA, HAHA) responses to monoclonal antibodies. Not four letter words. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2004;48(4):251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta LG. Selection, design, and engineering of therapeutic antibodies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;116(4):731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipriyanov SM, Little M. Generation of recombinantantibodies. Mol. Biotechnol. 1999;12(2):173–201. doi: 10.1385/MB:12:2:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson PJ, Souriau C. Engineered antibodies. Nat. Med. 2003;9(1):129–134. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]