Abstract

Purpose

To describe a patient complaining of ‘ghosting’ and ‘shadowing’ after bilateral, sequential cataract extraction with toric intraocular lens (IOL) implantation who was found to have significant eyelid ptosis.

Methods

The following is a case report.

Results

The patient's complaints arose a few weeks after surgery. By the second postoperative month, the patient's keratometry had changed compared to preoperative measurements. Because of significant ptosis, the patient underwent upper eyelid surgery. Four months later, he was found to have less corneal astigmatism than had been measured prior to cataract surgery. Following 2 stable examinations, a Prevue lens based on Hartmann-Shack wavefront aberrometry was made for each eye, which the patient said significantly improved his quality of vision. Wavefront-guided photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) was performed 6 months after cataract surgery. One year after PRK, the patient's symptoms had disappeared, his uncorrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/15 in the left, and he was satisfied with his quality of vision.

Conclusions

Bilateral toric IOLs were implanted in this patient based on measurements of corneal astigmatism that changed after cataract surgery and changed further after ptosis repair. This case demonstrates the importance of evaluating eyelid position in cataract surgical planning as ptosis can contribute significantly to corneal astigmatism. Patient education is important in the setting of higher expectations from purchase of premium lens implants.

Key Words: Ptosis, Corneal astigmatism, Toric lens implant, Wavefront aberrometry, Cataract surgery

Introduction

It is appreciated that eyelid lesions and malposition, such as congenital ptosis, can exert exogenous corneal deformation, resulting in significant astigmatic refractive error [1, 2, 3, 4], and similarly, that upper eyelid surgery can induce corneal topographic changes [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. We describe a patient who underwent cataract extraction with toric lens implants but whose worsening upper eyelid ptosis altered corneal astigmatism and may have precipitated visual complaints of monocular ‘ghosting’ and blurred vision.

Case Report

In March 2013, a 68-year-old Caucasian male sought consultation for bilateral, monocular ‘ghosting’ and ‘shadowing,’ worse in the right eye and adversely affecting his hobby, which is photography. He had undergone toric lens implantation elsewhere in January 2013. Prior to surgery, manual keratometry was 43.75/46.25 diopters × 24 degrees in the right eye and 44/45.37 × 168 in the left eye, both similar to keratometry using optical biometry; bilateral eyelid dermatochalasis was noted in the preoperative assessment. An Acrysof 16.5 diopter SN6AT5 (Alcon Laboratories, Ft. Worth, Tex., USA) lens was implanted in the right eye, and a 17.0 D SN6AT3 lens was implanted in the left eye. A month later and because of complaints of ‘ghosting’ and ‘shadowing,’ his surgeon obtained CustomVue Wavescans (Abbott Medical Optics, Santa Ana, Calif., USA), which showed a wavefront refraction of +0.34 + 0.70 × 163 in the right eye and +0.11 + 0.34 × 107 in the left.

At the time of consultation, he complained of a poor quality of vision that impaired his work and recreation, in addition to worsening upper eyelid ‘droop.’ UCVA was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left; manifest refraction (MR) of plano +1.00 × 165 in the right eye and +0.25 + 0.50 × 013 in the left eye yielded no improvement in Snellen acuity or in his complaint of monocular ‘ghosting’ at near and distance, which was worse in the right than in the left eye. The toric lens implants were positioned at the intended axes. Bilateral upper eyelid ptosis was present, preventing the ability to obtain topography. Keratometry using an optical biometer (Lenstar, Haag-Streit, Koeniz, Switzerland) was 44.20/46.31 × 023 in the right eye and 44.46/44.94 × 157 in the left, without lifting the eyelids.

He was sent to an oculoplastic surgeon who measured the upper eyelid margin to reflex distance of zero and 2–3+ dermatochalasis (fig. 1). Ptosis repair was performed in March 2013, but the patient still complained of a ‘doubling’ of vision, more in the right than in the left eye.

Fig. 1.

The patient prior to ptosis repair.

In July 2013, keratometry was 44.4/45.5 × 030 in the right eye and 44.6/45.7 × 132 in the left; very little posterior corneal astigmatism (–6.4 diopters and symmetric in both eyes) was detected on Pentacam (Oculus Inc., Arlington, Wash., USA). In August 2013, repeat keratometry and MR were stable at −0.25 + 1.00 × 112 in the right eye and −0.50 + 1.00 × 115 in the left, yielding 20/20 in each eye, but with the same complaints of ‘ghosting.’ Selecting the median wavefront refraction of −0.24 + 0.98 × 112 in the right eye and −0.52 + 1.01 × 105 in the left (fig. 2), a Prevue lens (AMO), based on Hartmann-Shack wavefront aberrometry, was cut. He stated that the Prevue lens greatly improved his symptoms. Therefore, the decision was made to proceed with wavefront-guided photorefractive keratectomy (PRK; VISX S4, AMO) rather than lens exchange. The surgery was uncomplicated. He was placed on antibiotic drops until the contact lens was removed and topical prednisolone acetate 1% four times a day, tapering over the next 6 months.

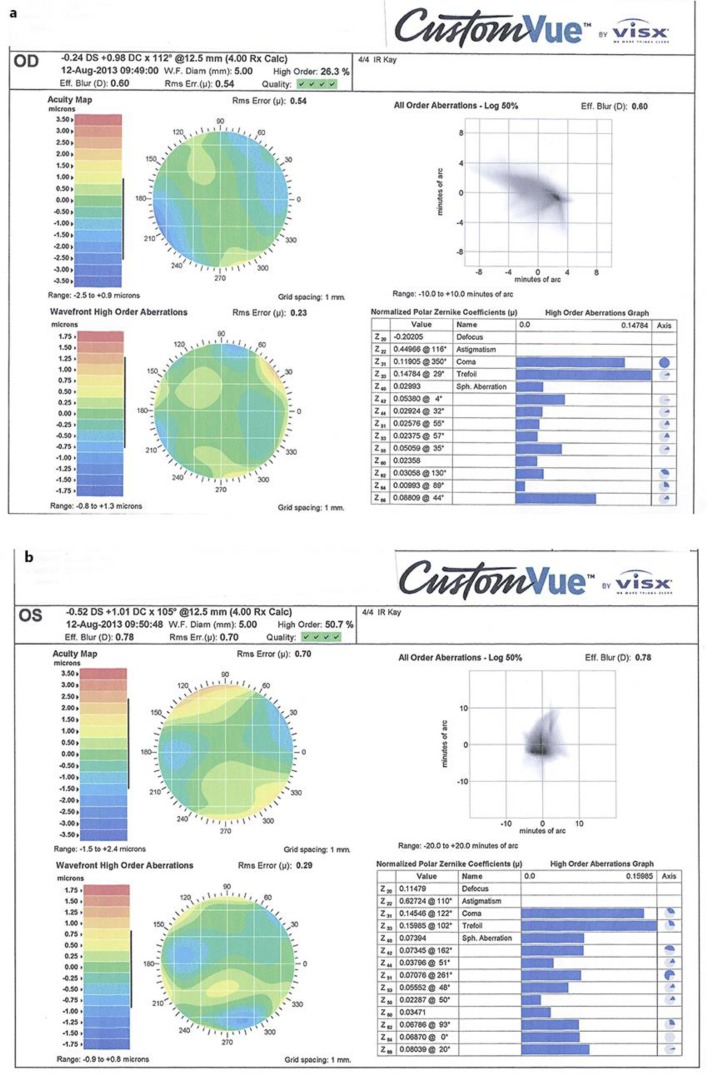

Fig. 2.

a, b Right and left eye Wavescans (VISX, Abbott Medical Optics) of the patient after ptosis repair and prior to PRK. In each eye, wavescan refraction was similar to manifest refraction in magnitude and axis of (with-the-rule) astigmatism, despite the fact that keratometry demonstrated against-the-rule and oblique steepening in the right and left eyes, respectively.

Six months after bilateral photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), his uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 20/40 in the right eye, improving to 20/15 with −0.75 + 0.75 × 032, and 20/30 in the left, improving to 20/15 with −0.50 + 0.25 × 180. One year after PRK, he was happy with his visual quality, UCVA was 20/20 in the right eye, improving to 20/15 with −0.75 + 0.50 × 010, and 20/15 in the left eye with plano correction.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the importance of evaluating a patient's eyelid position when planning cataract surgery as ptosis can contribute significantly to corneal astigmatism. Patient dissatisfaction with residual refractive error may be heightened by increased expectations borne from paying extra fees for premium lenses, such as toric lens implants. In this case, bilateral toric intraocular lenses (IOLs) were implanted based on measurements of corneal astigmatism done when the patient had documented dermatochalasis, and which changed after cataract surgery and further changed after ptosis repair. Five months after repair, this patient was able to undergo wavefront-guided PRK with good results. Importantly, PRK was done after establishing that keratometry, wavefront refraction and MR were stable over 2 sequential visits and after a successful Prevue lens trial.

Although classically it is taught that with-the-rule corneal astigmatism is induced by upper eyelid ptosis [10] (as occurred in this patient), a case series of 82 eyes of 43 patients with various degrees of dermatochalasis or ptosis showed that, after eyelid surgery, axis rotation was not systematic or predictable [9]. In another paper, most eyes after ptosis repair demonstrated an increased keratometric with-the-rule corneal astigmatism at 6 weeks (average: 1.11 D; range 0.62–1.93 D) that decreased by 12 months [8]. By altering the anterior corneal astigmatism, both ptosis and subsequent repair likely altered the intended effect of the toric implants in this patient. In addition, although magnitudes and axes of astigmatism (with-the-rule in both eyes) on both manifest and wavefront refractions were similar after ptosis repair and prior to PRK, they did not match the keratometric axes (against-the-rule in the right eye, oblique in the left). The posterior corneal astigmatism was minimal and symmetric. More likely, the keratometric axes did not match the manifest or wavefront cylindrical axes because the presence of the toric lens implants altered the manifest and wavefront refractions.

Toric lenses are intended for ‘visual correction of pre-existing corneal astigmatism’ (safety information, Acrysof IQ Toric IOL, Alcon). It is, however, important to distinguish ‘pre-existing’ from simply ‘preoperative’ and to recognize situations when keratometry may be affected by eyelid position. The eyelid position (and hence, corneal astigmatism) may even be in a state of flux, as in this patient, leading to patient dissatisfaction after cataract surgery.

The decision to perform PRK was made following stable refractive evaluations between month 4 and month 5 after ptosis repair. Yet another evaluation could have been performed, but given the stable nature of the findings at month 5, the patient's satisfaction with the Prevue lens at that point, and the patient's complaints about the inability to pursue his hobby since toric lens implantation 7 months earlier, PRK was performed 5 months after ptosis repair. PRK was chosen over laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis because of the small amount of refractive error and the possibility that creating a LASIK flap might induce more aberrations, [10, 11, 12] and because of the history of dry eye and blepharitis. Seven months after ptosis repair, he showed signs of recurrent dermatochalasis in the left eye (fig. 3); however, his refraction was stable. More aggressive repair might have prevented a recurrence.

Fig. 3.

The patient 7 months after ptosis repair.

Although cataract surgery can induce further levator detachment, leading to the recommendation that ptosis surgery be performed at least 3 months after cataract surgery [13], situations may arise where the sequence should be reversed to obtain optimal refractive outcomes. Alternatively, surgeons may counsel patients to consider a monofocal lens implant followed by eyelid surgery and possible laser refractive surgery. Given the increasing expectations of cataract surgery patients, especially those paying out-of-pocket fees for premium lens implants, a thorough preoperative discussion of treatment options is paramount.

Disclosure Statement

We received an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, N.Y., USA.

References

- 1.Merriam WW, Ellis FA, Helveston EM. Congenital blepharoptosis, anisometropia and amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson RL, Baumgartner SA. Amblyopia in ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:1068–1069. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020031058009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beniesh R, Williams F, Polomeno RC, Little JM, Ramsey B. Unilateral congenital ptosis and amblyopia. Can J Ophthalmol. 1983;18:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robb RM. Refractive errors associated with hemangiomas of the eyelids and orbit in infancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83:52–58. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown MS, Siegel IM, Lisman RD. Prospective analysis of changes in corneal topography after upper eyelid surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;15:378–383. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gingold MP, Ehlers WH, Rodgers RJ, Hornblass A. Changes in refraction and keratometry after surgery for acquired ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;10:241–246. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199412000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadera W, Orton RB, Hakim O. Changes in astigmatism after surgery for congenital ptosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1992;29:85–88. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19920301-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holck DE, Dutton JJ, Wehrly SR. Changes in astigmatism after ptosis surgery measured by corneal topography. Ophthal Plast Recontr Surg. 1998;14:151–158. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zinkernagel MS, Ebneter A, Ammann-Rauch D. Effect of upper eyelid surgery on corneal topography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.12.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo IC, Myrowitz E, Chuck RS, Schein OD. Wavefront-guided photorefractive keratectomy to correct ametropia following aspheric ReSTOR implantation. J Refract Surg. 2009:1111–1115. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090728-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mrochen M, Kaemmerer M, Seiler T. Clinical results of wavefront-guided laser in situ keratomileusis 3 months after surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pallikaris IG, Kymionis GD, Panagopoulou SI, Siganos CS, Theodorakis MA, Pallikaris AL. Induced optical aberrations following formation of a laser in situ keratomileusis flap. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:1737–1741. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gullstrand A. New York: Dover Publications Inc.; The cornea; in Southall JPC (ed): Helmholtz's Treatise Physiological Optics; pp. 320–321. [Google Scholar]