An 11-year-old healthy female presented to the emergency department with three days of worsening suprapubic pain, urinary retention, and constipation. She was afebrile with normal vital signs. Her physical examination was notable for suprapubic distention and bulging pink vaginal tissue at the introitus. Bedside ultrasound suggested a distended bladder. Placement of a Foley catheter returned 550mL of urine with improvement of the patient’s discomfort, but repeat ultrasound visualized a persistent hypoechoic mass adjacent to the newly decompressed bladder (Figure). The obstructive cause of her abdominal pain and urinary retention was revealed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis, which confirmed distal vaginal agenesis with uterine distention from hematometrocolpos (Figure). A Foley catheter was temporarily left in place, and after pediatric and gynecological consultation and operative intervention, she was later free of obstructive symptoms after surgical correction of her vaginal agenesis and hematometrocolpos.

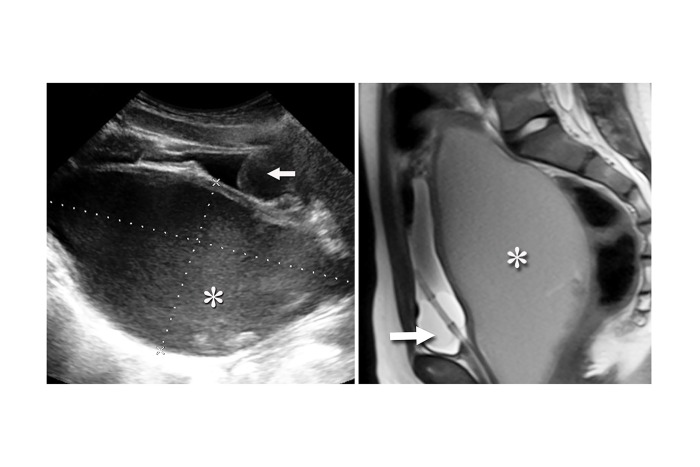

Figure.

Long axis transabdominal sonographic view (left) of the patient’s abdomen revealing intrauterine low-level echogenic material (asterisk) communicating with the vaginal vault and a Foley catheter within a decompressed bladder (arrow). Sagittal magnetic resonance image (right) demonstrating fluid-filled distention (asterisk) of the patient’s uterus and vagina to the level of the introitus and a Foley catheter within the decompressed bladder (arrow).

Müllerian duct abnormalities, such as imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and vaginal agenesis, may be associated with abdominal pain or other symptoms of pelvic outlet obstruction, hematocolpos, and amenorrhea in the early adolescent years.1–4 While the prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies is estimated at 6.7%, Müllerian agenesis with lack of vaginal or uterine development is thought to only occur in one out of every 4,000–10,000 females.1,2 These errors in development are strongly associated with a number of other congenital anomalies including urinary tract abnormalities such as renal agenesis in an estimated 18–40% of patients, particularly when a hymen is absent.3–5 Visualization of vaginal-appearing tissue on physical examination instead of bulging bluish tissue more indicative of an imperforate hymen may suggest vaginal agenesis, but both ultrasound and MRI are recommended to adequately characterize pelvic and neighboring anatomy.6

Footnotes

Section Editor: Sean O. Henderson, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saravelos SH, Cocksedge KA, Li T-C. Prevalence and diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies in women with reproductive failure: a critical appraisal. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14(5):415–29. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Committee opinion: no. 562: müllerian agenesis: diagnosis, management, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):1134–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000429659.93470.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Qayyum A, Coakley FV, et al. Association of renal agenesis and mullerian duct anomalies. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24(6):829–34. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvatore CA, Lodovicci O. Vaginal agenesis: an analysis of ninety cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1978;57(1):89–94. doi: 10.3109/00016347809154205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimberley N, Hutson JM, Southwell BR, et al. Vaginal agenesis, the hymen, and associated anomalies. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25(1):54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dursun I, Gunduz Z, Kucukaydin M, et al. Distal vaginal atresia resulting in obstructive uropathy accompanied by acute renal failure. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11(3):244–46. doi: 10.1007/s10157-007-0488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]