Abstract

Objective

We hypothesized that deficiency in 25-hydroxy vitamin D at critical care initiation would be associated with all cause mortality.

Design

Two-center observational study.

Setting

Two teaching hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts

Patients

1,325 patients, age ≥ 18 years, in whom 25-hydroxy vitamin D was measured 7 days prior to or after critical care initiation between 1998 and 2009.

Measurements

25-hydroxy vitamin D was categorized as deficiency in 25-hydroxy vitamin D (≤15 ng/mL), insufficiency (16–29 ng/mL) and sufficiency (≥30 ng/mL). Logistic regression examined death by days 30, 90 and 365 post-critical care initiation and in hospital mortality. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated by multivariable logistic regression models.

Interventions

None

Key Results

25-hydroxy vitamin D deficiency is predictive for short term and long term mortality. 30 days following critical care initiation, patients with 25-hydroxy vitamin D deficiency have an OR for mortality of 1.85 (95% CI, 1.15–2.98;P=0.01) relative to patients with 25-hydroxy vitamin D sufficiency. 25-hydroxy vitamin D deficiency remains a significant predictor of mortality at 30 days following critical care initiation following multivariable adjustment for age, gender, race, Deyo-Charlson index, sepsis, season, and surgical versus medical patient type (adjusted OR 1.94; 95% CI, 1.18–3.20;P=0.01). Results were similarly significant at 90 and 365 days following critical care initiation and for in hospital mortality. The association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by sepsis, race, or Neighborhood poverty rate, a proxy for socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

Deficiency of 25-hydroxy vitamin D at the time of critical care initiation is a significant predictor of all cause patient mortality in a critically ill patient population.

Introduction

Vitamin D is a fat soluble vitamin that is mainly produced in the skin by UV-B light conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol, or ingested in the diet from fatty fish, cod-liver oil, eggs, fortified milk products, or dietary supplements. Active vitamin D increases the intestinal absorption of calcium, and decreases renal calcium and phosphate excretion.(1) Vitamin D deficiency has been implicated in chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, autoimmune disorders, and increased overall mortality(2–5), but its role in morbidity and mortality of the critically ill is not well described.

Data on the exact prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the critically ill is limited. 17% of critically ill patients in a small prospective study had levels of vitamin D below assay limits.(6) Very low serum concentrations of 25 hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) and of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D) are documented in critically ill patients who have prolonged stays, likely related to decreased ultraviolet-B sunlight exposure and immobility.(7–11)

In the outpatient population, serum 25(OH)D is demonstrated to be stable three years between blood draws following adjustments for age, race, and season.(12) Using this observation, our group previously studied 2,399 critically ill patients demonstrating that 25(OH)D <30 ng/ml up to 365 days prior to hospital admission was a strong predictor of all cause mortality.(13)

The half-life of 25(OH)D is 15 days.(14) It is not known if vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency at the time of critical care affects survival or if critical illness alters vitamin D levels. Vitamin D has broad effects on immunity, inflammation, glucose and calcium metabolism, and endothelial and mucosal functions. The observed effects of vitamin D may be related to the presence of vitamin D receptor in a multiple cell types and organs and the production of 1,25(OH)2D in the kidney and in extrarenal organs.(15)

To explore the role of vitamin D deficiency at the time of critical care initiation in the outcome of critically ill patients, we performed an 11 year two-center observational study of patients among whom 25(OH)D was measured within 7 days before or 7 days after critical care initiation. The aim of this study is to determine the relationship between 25(OH)D deficiency at critical care initiation and subsequent mortality. Subanalyses will determine the effect of albumin, socioeconomic status and race on the relationship between 25(OH)D and mortality in our cohort.

Materials and Methods

Source Population

We extracted administrative and laboratory data from individuals admitted to 2 academic teaching hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts. Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) is a 777-bed teaching hospital with 100 critical care beds. Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) is a 902-bed teaching hospital with 109 critical care beds. The two hospitals provide primary as well as tertiary care to an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population within eastern Massachusetts and the surrounding region.

Data Sources

Data on all patients admitted to BWH or MGH between November 2, 1997 and April 1, 2009 were obtained through a computerized registry which serves as a central clinical data warehouse for all inpatients and outpatients seen at these hospitals. The administrative database used in this cohort study is called the Research Patient Data Registry, a registry maintained by the administrative body that oversees operations at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital.(16) The database contains information on demographics, medications, laboratory values, microbiology data, procedures and the records of inpatient and outpatients. This administrative database has been used for other clinical studies. (13, 17–19) Approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of BWH. The Institutional Review Board waived the need for informed consent.

The following data were retrieved: Demographics, Vital status for up to 11 years following critical care initiation, 25(OH)D measured between 7 days prior and 7 days after critical care initiation, year and season 25(OH)D was measured, microbiology data, latitude of patient address, hospital admission and discharge date, Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) assigned at discharge, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9CM) codes, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for in-hospital procedures.

Study Population

During the 11-year period of study there were 56,604 unique patients, age ≥ 18 years, who were assigned the CPT code 99291 (critical care, first 30–74 minutes). 2,212 patients with multiple admissions to the hospital involving critical care (CPT code 99291 assignment) were identified and excluded. 205 foreign patients without Social Security Numbers were identified and excluded as vital status in this study is determined by the Social Security Administration Master Death File. We excluded 2,372 patients assigned CPT code 99291 who received care only in the Emergency Room, were not admitted and were not assigned a DRG. 51,815 patients constituted the Total Critical Care population. This Total Critical Care population has been previously described by our group.(13)

A total of 1,327 patients in the Total Critical Care population had blood for 25(OH)D measurement drawn within 7 days before or 7 days after the first day of CPT code 99291 assignment. 85 of the 1,327 patients also had 25(OH)D levels measured up to a year prior to the hospital admission related to critical care initiation. These 85 patients were identified but not excluded. 2 of the 1,327 patients who received high dose vitamin D supplementation during the hospitalization following the 25(OH)D level draw date were identified and excluded. 1,325 patients constituted the study cohort. This 1,327 patient study cohort did not share any patients with our prior vitamin D study.(13)

Exposure of Interest and Comorbidities

The exposure of interest was 25(OH)D measured in inpatients once during the time range from 7 days prior to critical care initiation to 7 days after critical care initiation. 25(OH)D was categorized a priori as deficiency (25(OH)D ≤15 ng/mL), insufficiency (25(OH)D 16–29 ng/mL) and sufficiency (25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL).(12)

We utilized the Deyo-Charlson index to assess the burden of chronic illness.(20) The Deyo-Charlson index consists of 17 co-morbidities, which are weighted and summed to produce a score each with an associated weight based on the adjusted risk of one-year mortality. This score ranges from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating a higher burden. The score does not measure type or severity of acute illness.(20–21) We employed the ICD-9 coding algorithms developed by Quan et al(22) to derive a co-morbidity score for each patient. The validity of the algorithms by Quan et al for ICD-9 coding from administrative data is reported.(22) For the Deyo-Charlson index, ICD-9 codes were obtained prior to and during hospitalization. Due to scant representation, Deyo-Charlson index scores ≥ 6 were combined.

We used 1990 decennial US Census to obtain the percentage of residents living in poverty per census tract(23) and merged these data with our data set following geocoding. The percentage of the population living below the federal poverty level has been used previously to describe social inequities in health.(24–26) Neighborhood Poverty was defined by residence in a census tract with at least 20% of persons below the federal poverty level according to the 1990 decennial US Census.(24, 27–31) In our data, the Census tract level corresponded to a small neighborhood with an average of 1,512 (SD 800) residents. Census tracts are common to area-based socioeconomic studies of neighborhood effects on health(32–34) and provide more precise estimates than ZIP or post codes.(24, 35) In this study, Neighborhood Poverty rate was stratified a priori into <20% and ≥20%, categories based on previous literature.(36–38)

Sepsis was adapted from Martin et al(36) and defined by the presence of any of the following ICD-9-CM codes during hospitalization: 038.0–038.9, 790.7, 117.9, 112.5, 112.81, 995.92, 785.52. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined as ICD-9-CM 584.5, 584.6, 584.7, 584.8, or 584.9 seven days prior to three days after critical care initiation.(19) Procedures recorded included CABG surgery performed on the day prior or after critical care initiation (CPT codes 33510 to 33536). Number of organs with failure was adapted from Martin et al(39) and defined by a combination of ICD-9-CM and CPT codes relating to acute organ dysfunction assigned from 3 days prior to critical care initiation to 30 days after critical care initiation, as outlined in the Supplemental Digital Content. Patient Type is defined as Medical or Surgical and incorporates the Diagnostic Related Grouping (DRG) methodology, devised by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).(40) Trauma status also incorporates the Diagnostic Related Grouping (DRG) methodology. Laboratory data was obtained closest to the first hour of the first day of CPT code 99291 assignment.

Assessment of Mortality

Information on vital status for the study cohort was obtained from the Social Security Administration Death Master File. Data from the Social Security Administration Death Master File has a reported sensitivity for mortality up to 92.1% with a specificity of 99.9%, in comparison to >95% with National Death Index as the gold standard.(41–44) The administrative database from which our study cohort is derived is updated monthly using Social Security Administration Death Master File, which itself is updated weekly.(43) Utilization of the Death Master File allows for long term follow-up of patients following hospital discharge. The censoring date was April 2, 2010.

End Points

The primary end point was 30-day mortality following critical care initiation. Pre-specified secondary end points included 90-day, 365-day and in-hospital mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical covariates were described by frequency distribution, and compared across vitamin D groups using contingency tables and chi-square testing. Continuous covariates were examined graphically (e.g., histogram, box plot) and in terms of summary statistics (mean, SD, median, inter-quartile range), and compared across exposure groups using one-way ANOVA. The outcomes considered were death by days 30, 90 and 365 post-critical care initiation and in hospital mortality.

Unadjusted associations between vitamin D groups and outcomes were estimated by contingency tables, chi square testing, and by bivariable logistic regression analysis. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated by multivariable logistic regression models with inclusion of covariate terms thought to plausibly interact with both vitamin D levels and mortality. For the primary model (30-day mortality), specification of each continuous covariate (as a linear versus categorical term) was adjudicated by the empiric association with the primary outcome using Akaike’s Information Criterion; overall model fit was assessed using the Hosmer Lemeshow test. Models for secondary analyses (90-day, 365-day and in-hospital mortality) were specified identically to the primary model in order to bear greatest analogy. For the time to mortality we estimated the survival curves according to group with the use of the Kaplan-Meier method(45) and compared the results by means of the log-rank test.

To minimize tertiary referral patterns we conducted a sensitivity analysis considering in-hospital, 30-day, 90-day, and 365-day mortality in patients who live within 50 miles to the hospital where they received critical care. Analyses were analogous to the above. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were performed for patients with regard to race (white relative to non-white, white relative to black and also white relative to Hispanic patients). Hypothesizing that Neighborhood Poverty rate might bear differential association to survival among vitamin D deficient patients, we conducted a sensitivity analysis considering 30-day mortality in patients with high Neighborhood Poverty rate. In a subset of patients with albumin measured at critical care initiation, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of hypoalbuminemia. We assessed possible effect modification of sepsis on the risk of mortality and tested the significance of the interaction using the likelihood-ratio test. All p-values presented are two-tailed; values below 0.05 were considered nominally significant. All analyses are performed using STATA 10.0MP (College Station, TX).

Results

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of the study population. The majority of patients were male (52.1%), white (79.3%) and had medical related DRGs (53.8%). The mean age at critical care initiation was 63.0 (SD 17.2) years. The mean Latitude was 42.2 (SD 1.5) degrees North. The mean 25(OH)D was 18.2 (SD 13.7) ng/mL. In the cohort, 668 (50.4%) were vitamin D deficient, 472 (35.6%) insufficient and 185 (14.0%) sufficient. The majority of vitamin D measurements occurred on the day of or on the days after critical care initiation (<3 to 7 days prior 7.8%, <0 to 3 days prior 9.8%, ≥0 days to 3 days after 41.5%, ≥3 to 7 days after 40.9%). In the 85 patients with previous 25(OH)D level measured within the prior year and at the time of critical care initiation, 25(OH)D declined in 59 patients with a mean decrease in 25(OH)D of 12.5 (SD 10.0) ng/mL whereas in 26 patients the 25(OH)D increased by a mean of 9.94 (SD 8.15).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of the Study Population

| Study Cohort | Total Critical Care Population | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1,325 | 51,815 | |

| Gender-no.(%) | <.0001 | ||

| Female | 635 (47.9) | 21,671 (41.8) | |

| Male | 690 (52.1) | 30,144 (58.2) | |

| Race-no.(%) | 0.8 | ||

| White | 1,051 (79.3) | 41,235 (79.6) | |

| Non-white | 274 (20.7) | 10,580 (20.4) | |

| Age at critical care initiation mean (SD) | 63.0 (17.2) | 61.69 (18.4) | 0.01 |

| Latitude mean (SD) | 42.2 (1.5) | 42.2 (1.6) | 1.0 |

| Deyo-Charlson Index mean (SD) | 3.8 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.1) | <.0001 |

| 25(OH)D mean (SD) | 18.2 (13.7) | -- -- | |

| Patient Type-no.(%) | 0.02 | ||

| Medical | 713 (53.8) | 26,221 (50.6) | |

| Surgical | 612 (46.2) | 25,596 (49.4) | |

| Events-no.(%) | |||

| Acute Myocardial Infarct | 200 (15.1) | 7,981 (15.4) | 0.8 |

| Sepsis | 426 (32.0) | 8,059 (15.6) | <.0001 |

| CABG | 44 (3.3) | 2,822 (5.4) | <.0001 |

| Mortality Rates % | |||

| 30-day | 17.2 | 14.2 | 0.002 |

| 90-day | 24.2 | 18.7 | <.0001 |

| 365-day | 34.7 | 26.3 | <.0001 |

| In-hospital | 16.5 | 13.0 | <.0001 |

| No. of organs with failure- no.(%) | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | 224 (16.9) | 20,067 (38.7) | |

| 1 | 412 (31.1) | 17,731 (34.2) | |

| 2 | 345 (26.0) | 8,654 (16.7) | |

| ≥3 | 344 (26.0) | 5,363 (10.4) | |

| Creatinine- no.(%) | <.0001 | ||

| ≤0.8 mg/dl | 230 (17.4) | 14,834 (28.6) | |

| 0.8–1.5 mg/dl | 554 (41.8) | 26,748 (51.6) | |

| 1.5–3.0 mg/dl | 265 (20.0) | 7,156 (13.8) | |

| >3.0 mg/dl | 276 (20.8) | 3,077 (5.9) |

Based on DRG criteria no trauma patients were identified. Based upon ICD-9-CM code criteria, 364 patients were identified with sepsis, 410 patients had acute kidney injury. In the study cohort, procedures included CABG surgery in 44. Due to scant representation CABG surgery was not further analyzed in the cohort.

The study cohort differs from the Total Critical Care population in the period studied. In general, the study cohort is an older group with, higher comorbidity (Deyo-Charlson Index), more women, more sepsis, higher number of organs with failure, fewer surgical patients, fewer CABG and higher mortality than the Total Critical Care population. (Table 1).

Table 2 indicates that 25(OH)D, age, gender, patient type, sepsis and number of organs with failure are significant predictors of mortality at 30 days following critical care initiation. Non-significant predictors of 30 day mortality include race, season of 25(OH)D blood draw, and the Deyo-Charlson Index.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for 30-day mortality

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25(OH)D | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.83 | 1.10–3.05 | 0.02 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.32 | 0.78–2.26 | 0.3 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| Age^^ | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | <.0001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.56 | 0.41–0.76 | <.0001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1.00 | ||

| Non-white | 0.95 | 0.64–1.42 | 0.8 |

| Patient Type-no.(%) | |||

| Medicine | 1.00 | ||

| Surgery | 0.53 | 0.39–0.73 | <.0001 |

| Season 25(OH)D drawn-no.(%) | |||

| Winter | 1.00 | ||

| Spring | 0.72 | 0.47–1.11 | 0.1 |

| Summer | 0.93 | 0.61–1.43 | 0.7 |

| Fall | 0.92 | 0.60–1.41 | 0.7 |

| Deyo-Charlson Index | |||

| 1 | 0.35 | 0.16–0.76 | 0.008 |

| 2^ | 1.00 | ||

| 3 | 1.02 | 0.60–1.71 | 0.9 |

| 4 | 1.13 | 0.68–1.88 | 0.6 |

| 5 | 1.16 | 0.67–1.99 | 0.6 |

| ≥ 6 | 1.35 | 0.82–2.22 | 0.2 |

| Sepsis | |||

| Sepsis absent | 1.00 | ||

| Sepsis present | 1.80 | 1.29–2.50 | <.0001 |

| No. of organs with failure | |||

| 0 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 2.17 | 1.17–4.02 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 3.53 | 1.90–6.53 | <.0001 |

| 3 | 4.77 | 2.48–9.15 | <.0001 |

| ≥4 | 6.51 | 3.19–13.30 | <.0001 |

| Creatinine | |||

| ≤0.8 mg/dl | 1.25 | 0.78 –1.98 | 0.4 |

| 0.8–1.5 mg/dl | 1.00 | ||

| 1.5–3.0 mg/dl | 0.76 | 0.50–1.14 | 0.2 |

| >3.0 mg/dl | 0.60 | 0.39–0.93 | 0.02 |

Note: Estimates for each variable are adjusted for all other variables in the table.

comorbidity score of 2 was chosen as the referent category due to convergence issues as no patients with a comorbidity score of 0 died by day 30.

Age is per year increment.

Seasons are defined as Winter (December, January, February), Spring (March, April, May), Summer (June, July, August), Fall (September, October, November).

Patient characteristics of the study cohort were stratified according to 25(OH)D levels (Table 3). Factors that significantly differed between stratified groups included age, race, and sepsis. Factors that did not significantly differ between stratified groups included gender, Deyo-Charlson Index, season of 25(OH)D draw, creatinine at critical care initiation date and patient type. We did not adjust for the number of organs with failure variable in the primary outcome due to overlap of ICD-9 codes with the Deyo-Charlson Index.

Table 3.

Stratified Patient Characteristics of the 25(OH)D Cohort

| 25(OH)D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 15 ng/mL | 15–30 ng/mL | ≥ 30 ng/mL | P-value | |

| N(%) | 668 (50.4) | 472 (35.6) | 185 (14.0) | |

| Age-mean(SD) | 61.0 (17.0) | 64.8 (17.1) | 66.1 (17.1) | <.0001 |

| Gender-no.(%) | 0.2 | |||

| Female | 320 (47.9) | 237 (50.2) | 78 (42.2) | |

| Male | 348 (52.1) | 235 (49.8) | 107 (57.8) | |

| Race-no.(%) | <.0001 | |||

| White | 501 (75.0) | 389 (82.4) | 161 (87.0) | |

| Non-White | 167 (25.0) | 83 (17.6) | 24 (13.0) | |

| Patient Type-no.(%) | 0.2 | |||

| Medical | 348 (52.1) | 255 (54.0) | 110 (59.5) | |

| Surgical | 320 (47.9) | 217 (46.0) | 75 (40.5) | |

| Season 25(OH)D drawn-no.(%) | 0.7 | |||

| Winter | 175 (26.2) | 105 (22.3) | 44 (23.8) | |

| Spring | 175 (26.2) | 119 (25.2) | 44 (23.8) | |

| Summer | 160 (24.0) | 131 (27.8) | 49 (26.5) | |

| Fall | 158 (23.7) | 117 (24.8) | 48 (26.0) | |

| Deyo-Charlson Index-no.(%) | 0.4 | |||

| 0 | 16 (2.4) | 15 (3.2) | 8 (4.3) | |

| 1 | 70 (10.5) | 48 (10.2) | 25 (13.5) | |

| 2 | 113 (16.9) | 79 (16.7) | 32 (17.3) | |

| 3 | 119 (17.8) | 93 (19.7) | 26 (14.1) | |

| 4 | 120 (18.0) | 89 (18.9) | 22 (11.9) | |

| 5 | 93 (13.9) | 56 (11.9) | 28 (15.1) | |

| ≥ 6 | 137 (20.5) | 92 (19.5) | 44 (23.8) | |

| Sepsis-no.(%) | 249 (37.3) | 135 (28.6) | 42 (22.1) | <.0001 |

| No. of organs with failure-no.(%) | 0.009 | |||

| 0 | 93 (13.9) | 93 (19.7) | 37 (20.0) | |

| 1 | 199 (29.8) | 144 (30.5) | 69 (37.3) | |

| 2 | 179 (26.8) | 122 (25.8) | 43 (23.2) | |

| ≥ 3 | 197 (29.4) | 113 (23.9) | 36 (19.5) | |

| Creatinine-no.(%) | 0.005 | |||

| ≤ 0.8 mg/dl | 133 (19.9) | 70 (14.8) | 27(14.6) | |

| 0.8–1.5 mg/dl | 255 (38.2) | 228 (48.3) | 71 (38.4) | |

| 1.5–3.0 mg/dl | 138 (20.7) | 79 (16.7) | 48 (26.0) | |

| > 3.0 mg/dl | 142 (21.3) | 95 (20.1) | 39 (21.1) | |

Primary Outcome

25(OH)D was a strong predictor of all-cause mortality with a significant risk gradient across 25(OH)D groups (Table 4). The risk of mortality 30 days following critical care initiation in patients with 25(OH)D values in the deficient group was 1.9-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. 25(OH)D in the cohort remains a significant predictor of risk of mortality following adjustment for age, sex, race, Deyo-Charlson index, season, type (surgical versus medical) and sepsis. The adjusted risk of mortality in the deficient group was 1.9-fold that of the vitamin D sufficiency group. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations between 25(OH)D level and outcomes

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||

| 30-day mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.85 | 1.15–2.98 | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.31 | 0.79–2.16 | 0.3 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| 90-day mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.69 | 1.12–2.54 | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.22 | 0.79–1.88 | 0.4 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| 365-day mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.55 | 1.08–2.22 | 0.02 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.36 | 0.94–1.98 | 0.1 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.92 | 1.16–3.17 | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.49 | 0.88–2.52 | 0.1 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| Adjusted | |||

| 30-day mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.94 | 1.17–3.21 | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.35 | 0.80–2.27 | 0.3 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| 90-day mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.78 | 1.14–2.76 | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.28 | 0.81–2.02 | 0.3 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| 365-day mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.65 | 1.12–2.43 | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.41 | 0.94–2.10 | 0.09 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 | ||

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/mL | 1.77 | 1.04–3.01 | 0.03 |

| 25(OH)D 15–30 ng/mL | 1.47 | 0.85–2.55 | 0.2 |

| 25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL | 1.00 |

Note: Estimates adjusted for age, gender, race (white, non-white), Deyo-Charlson index, season, type (surgical versus medical), creatinine and sepsis.

Secondary Outcomes

The risk of mortality 90 days following critical care initiation in patients in the 25(OH)D deficient group was 1.7-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. The multivariable adjusted risk of mortality in the 25(OH)D deficient group was 1.8-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. (Table 4)

The risk of mortality 365 days following critical care initiation in patients in the 25(OH)D deficient group was 1.6-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. The multivariable adjusted risk of mortality in the 25(OH)D deficient group was 1.7-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. (Table 4)

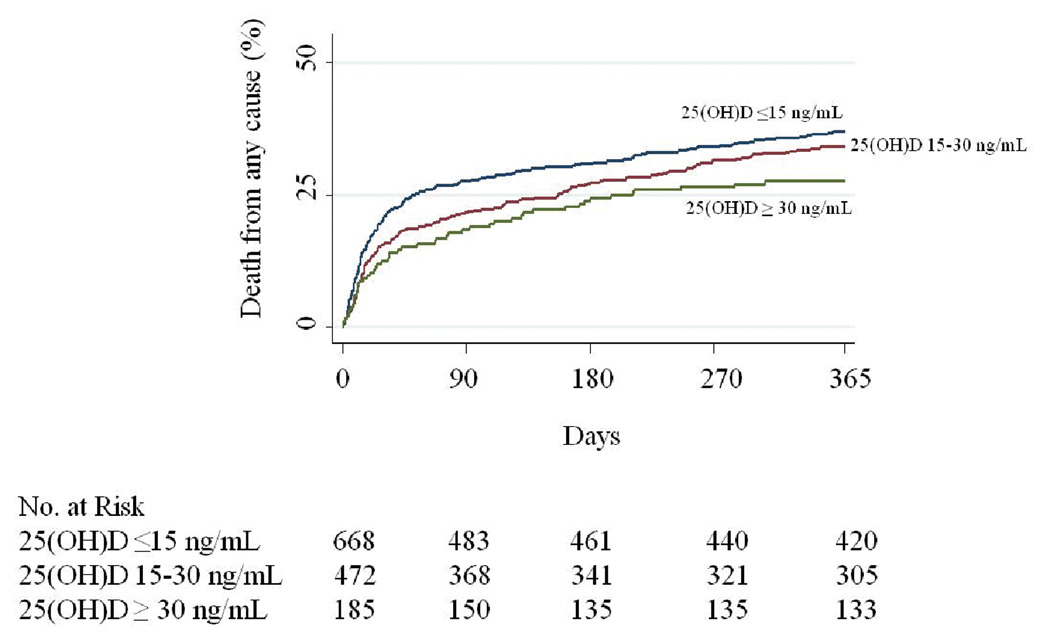

The risk of in-hospital mortality following critical care initiation in patients in the 25(OH)D deficient group was 1.9-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. The multivariable adjusted risk of mortality in the 25(OH)D deficient group was 1.8-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency. (Table 4) Figure 1 shows the unadjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates for the time to death where the difference between the 25(OH)D groups was significant (P=0.04 by the log-rank test) and appears strongest prior to 45 days. The association between 25(OH)D and 30 day mortality was not materially modified with additional covariate adjustment for number of organs with failure variable (data not shown).

Figure 1. Time-to-Event curves for the Primary End Point.

Note: Unadjusted event rates were calculated with the use of the Kaplan-Meier methods and compared with the use of the log-rank test. Observations are censored at 1-year. Categorization of 25(OH)D is per the primary analyses. The global comparison log rank p value is 0.04.

Effect modification and Subanalyses

In a subanalysis we further categorized 25(OH)D as severe deficiency (25(OH)D ≤10 ng/mL), deficiency (25(OH)D 10–15 ng/mL), insufficiency (25(OH)D 16–29 ng/mL) and sufficiency (25(OH)D ≥ 30 ng/mL). The risk of mortality 30 days following critical care initiation in patients with 25(OH)D values in the severe deficiency group was 1.9-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency (OR 1.87; 95%CI, 1.11–3.13; P=0.02). 25(OH)D in the cohort remains a significant predictor of risk of mortality following multivariable adjustment. The adjusted risk of 30 day mortality in patients with 25(OH)D values in the severe deficiency group range (≤10 ng/mL)was 2.0-fold that of those with vitamin D sufficiency(OR 1.95; 95%CI, 1.13–3.39; P=0.02), data not shown.

The association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by the presence or absence of sepsis (P-interaction: 30 day = 0.52, 90 day = 0.82, 365 day = 0.58, in-hospital = 0.93). The association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by the presence of creatinine > 1.5mg/dl (P-interaction: 30 day = 0.44, 90 day = 0.80, 365 day = 0.54, in-hospital = 0.66). The association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by season (winter /spring versus summer/fall P-interaction: 30 day = 0.98, 90 day = 0.65, 365 day = 0.80, in-hospital = 0.68). The association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by race (white versus non-white P-interaction: 30 day = 0.52, 90 day = 0.21, 365 day = 0.35, in-hospital = 0.55; white versus black P-interaction: 30 day = 0.57, 90 day = 0.37, 365 day = 0.63, in-hospital = 0.61). There were too few Hispanic cohort patients to provide meaningful analysis regarding effect modification. In a subanalysis of 856 cohort patients with albumin levels present at critical care initiation, the association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by the presence of albumin ≤ 2.5 g/dl (P-interaction: 30 day = 0.15, 90 day = 0.79, 365 day = 0.70, in-hospital = 0.71). In a subanalysis of 1,038 cohort patients whose address geocoded and matched the 1990 US Census file, the association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by the presence or absence of high (>20%) Neighborhood poverty rate (P-interaction: 30 day = 0.90, 90 day = 0.91, 365 day = 0.58, in-hospital = 0.17).

Finally, 25(OH)D was expressed as a continuous variable adjusted for age, gender, race, Deyo-Charlson index, season, patient type, creatinine and sepsis. The odds for 30-day mortality was 0.98 (95%CI, 0.96–0.99; P=0.001). Importantly, this result is multiplicative, so a 1 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D would have an OR of 0.975 effect on the risk of mortality (a reduction of 2.5%), a 5 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D would have an OR of 0.975^5 effect on the risk (=0.88 or a mortality reduction of 12%) and a 10 ng/mL increase would have an OR of 0.975^10 effect (=0.78 or a mortality reduction of 22%). Effect modification was then determined with 25(OH)D expressed as a continuous variable and albumin ≤ 2.5 g/dl (the effect modifier) also expressed as a continuous variable. In patients with albumin levels present, the association between vitamin D and mortality was not modified by the presence of albumin ≤ 2.5 g/dl (P-interaction: 30 day = 0.87, 90 day = 0.40, 365 day = 0.65, in-hospital = 0.73).

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to determine if 25(OH)D levels at the time of critical care initiation were associated with all-cause mortality. Our 11-year two-center observational study demonstrates the increased mortality risk related to 25(OH)D deficiency at the time of critical care initiation. 25(OH)D deficiency was a significant predictor of 30, 90, 365 day all-cause mortality as well as in-hospital mortality, and it remained a significant predictor of mortality following multivariable adjustments for relevant comorbidities.

It is not known if critical illness alters vitamin D levels. Nutritional biomarkers altered by the systemic response to inflammation include albumin, serum iron, vitamins A, C, E and other negative acute phase reactants.(46–50) In our cohort, 85 patients had 25(OH)D measured at critical care initiation and also within a year prior. While a majority of patients had a decrease in 25(OH)D at the time of critical care, a third saw an increase in 25(OH)D. We postulate that in those whose 25(OH)D increased, supplementation as an outpatient was administered. In those whose 25(OH)D decreased, the days to weeks leading up to an ICU admission may have been a factor due to inflammation, immobility or reduced sun exposure. Alternatively, the critical illness itself may create a vitamin D deficiency state by an unclear mechanism. Importantly, a deficiency state defined by a nutritional biomarker when not acutely ill often does not increase the susceptibility to illness, but this same marker taken at the time of the critical illness in many instances reflects the criticality of the illness and not the nutritional state.

Patients with sepsis as defined in our study had an increased 30-day mortality following critical care.(Table 2) Sepsis significantly differed between 25(OH)D groups with the highest in the 25(OH)D deficient group.(Table 3). The observed vitamin D and mortality association is not modified by the presence of sepsis. The interaction tests suggest that the association between 25(OH)D level and mortality is the same in septic patients as in non-septic patients.

In our study we evaluate Neighborhood Poverty rate as a proxy of socioeconomic status to describe social inequities in health(24–26) as it relates to vitamin D sufficiency. Groups with higher SES have consistently higher intakes of most vitamins relative to lower SES groups.(51) The effect of vitamin D on mortality does not appear to differ by Neighborhood Poverty rate ≥ 20%. Outcomes research has shown that race and SES are separate variables that merit investigation.(52) We find that the effect of vitamin D on mortality does not appear to differ in our cohort non-white patients relative to whites or African American patients relative to whites.

The findings of the current study extend and complement and extend our previous report, (13) where we showed that low circulating 25(OH)D levels up to one year prior to hospital admission were associated with worse outcomes in 2,399 adults following critical care initiation. In comparison to the current study cohort, our previously reported study cohort(13) was predominantly female (57.0% versus 47.9%), had higher Deyo-Charlson Index (mean 5.6 versus 3.8), higher 25(OH)D (mean 26.4 versus 18.2), fewer patients with sepsis (24.1% versus 27.5%), fewer patients with failure of ≥3 organs (12.0% versus 26.0%) and lower 30-day mortality (16.7% versus 17.2%). A significant limitation of our previous report was the investigation of vitamin D levels up to one year prior to critical care initiation.(13) The current report now investigates vitamin D levels at critical care initiation, evaluates the effect of race, socioeconomic status on our observed association between hypovitaminosis D and mortality.

The potential benefit of vitamin D sufficiency appears to occur in the first 45 days following critical care initiation.(Figure 1) This observation and the high odds ratio for death at 30 days improves the biological plausibility or at least relevancy of vitamin D sufficiency to the early acute critical illness period. A biologically plausible mechanism for why vitamin D deficiency is associated with mortality after a critical illness may be found in the numerous and diverse functions of vitamin D. Vitamin D inhibits vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation,(53) protects normal endothelial function,(54) and modulates inflammatory processes.(55–56) Vitamin D deficiency is found worldwide in young adults, the middle-aged and the elderly.(57–58) Severe vitamin D deficiency is reported to be related to susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections(59), tuberculosis(60) and infection in general.(61–62) A meta-analysis of 18 trials involving 57,311 subjects, demonstrated a 7% reduction of all-cause mortality in those supplemented with vitamin D.(5) These observations and others suggest that vitamin D deficiency is likely to play a key role in infection, and cardiac and metabolic dysfunctions in critically ill patients.

1,25(OH) 2D primarily inhibits adaptive immunity but also has stimulatory effects on innate immunity.(63) Vitamin D deficiency leads to defects in macrophage function related to phagocytosis, chemotaxis and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.(64) Vitamin D plays a key role linking Toll Like Receptor (TLR) activation and antibacterial responses in innate immunity.(65) TLR stimulation of human macrophages induces the conversion of 25(OH)D to active 1,25(OH)2D; the expression of the vitamin D receptor; and the production of cathelicidin a downstream target of the vitamin D receptor capable of promoting innate immunity.(66–68) Cathelicidin is active against a broad spectrum of infectious agents including gram negative and positive bacteria and fungi.(69) Cathelicidin deactivates lipopolysaccharide and also acts as a chemo-attractant for T cells, neutrophils and monocytes.(70) Vitamin D also regulates the expression of β-defensin, an antimicrobial peptide with epithelial surface defense function.(71)

Vitamin D promotes the induction of T-Regulatory cells(72–74) which appear to play a major role in the suppression of immune reactivity in injury(75–76) and infection (77). Patients with sepsis have increased numbers of T-Regulatory cells in circulation.(78) Septic patients have decreases in immune responsiveness predisposing to nosocomial infections.(79) Immune suppression is also observed with surgical procedures, trauma, burn injury, or hemorrhage which can predispose patients to nosocomial infections.(80–81) In such inflammatory or injury states, a decrease in the counter-regulatory process from T-Regulatory cells via deficient vitamin D may result in dysfunctional responses to sepsis, inflammation and injury which may result in the increased mortality observed in our study.

The present study has limitations. The study was performed in a tertiary referral center and thus is limited in its generalizability. The patient population is entirely composed of patients seen at an academic medical center which may not be reflective of practices at non-academic institutions. Selection bias may exist as vitamin D levels may be obtained for a particular reason that is absent in other critically ill patients. A comparison of the Total Critical Care population with the study cohort illustrates the differences between the groups.(Table 1) Due to database limitations, information on outpatient vitamin D supplementation following critical care is not present. Patients who are treated with vitamin D supplementation as outpatients following critical care may have a long term survival advantage which is a limitation of our study. It is not known if critical illness is associated with decreasing 25(OH)D levels. Thus, reverse causation may be present as critical illness may lower 25(OH)D levels. However, in the light of our previous findings where we showed that more remote 25(OH)D levels are also related to mortality following critical care(13), reverse causation is less likely an explanation of our current findings.

In our study, sepsis and comorbidity is defined based on administrative ICD-9-CM coding. Administrative coding has been studied in particular diseases(82–86) and comorbidities.(87–88) ICD-9-CM coding accuracy for the identification of medical conditions is controversial.(39) Algorithms developed to recode ICD-9-CM coded data into a Deyo-Charlson index are well studied, validated and well suited for use in administrative datasets.(89–90) Although the ICD-9-CM code 038.x has a high positive predictive value(39) and high negative predictive value(39) for true cases of sepsis, our reliance only on ICD-9-CM codes to define sepsis is a limitation with regard to the accuracy of our definition of sepsis in our administrative dataset. The lack of effect modification by sepsis on the vitamin D-mortality association may be related to the definition of sepsis by ICD-9-CM codes rather than the 2001 SCCM/ESICM, ACCP, ATS, SIS international sepsis definitions conference guidelines.(91)

Due to data limitations, we are unable to adjust for physiologic data in our cohort. In the administrative database used in this study, APACHE II scores are not present, as data on temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and Glasgow Coma scale are not recorded. The absence of scoring systems inclusive of physiological data is a limitation as such scores are strong predictors of mortality in critically ill patients.(92) In the absence of physiologic data, the addition of age and gender data to the Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index is considered an alternative method of risk adjustment.(93) Furthermore, addition of an acute organ dysfunction score (number of failed organs variable) to the risk adjustment did not materially change the association between 25(OH)D and 30 day mortality. Lack of scoring systems inclusive of physiological data or an acute organ dysfunction score in our study limits the interpretability of the results by ICU clinicians.

Other variables that are not measureable may influence mortality independently of vitamin D, which may have biased estimates. Residual confounding variables may exist despite adjusting for potential confounders contributing to our observed data. Covariate factors that can alter 25(OH)D such as body mass index, immobilization, lack of sun exposure and cigarette smoking status were not available for our study. Finally due to limitations of the dataset and ICD9 coding accuracy issues, we are unable to determine End Stage Renal Disease or Chronic Kidney Disease status with confidence for the majority of the cohort. (94–99) Although stratification of creatinine at critical care initiation cannot distinguish between patients with chronic kidney disease alone, acute kidney injury alone or acute kidney injury in combination with chronic kidney disease, it does reflect the creatinine at critical care initiation which we have previously shown is associated with mortality in the “Total Critical Care Population” shown in Table 1. (100)

The present study has several strengths. All-cause mortality is considered a clinically relevant and unbiased outcome in long-term observational studies.(101–102) The Social Security Administration Death Master File allows for long term follow up of all patients in the study cohort. With a large number of patients and a mortality rate of 16.5%, we can have confidence in the reliability of our mortality estimates. Our use of prior records to define the Deyo-Charlson Index increases the prevalence of the conditions of interest and improves risk adjustment.(84, 103) We have previously validated the accuracy of CPT code 99291 assignment for ICU admission and the accuracy of the Social Security Administration Death Master File for in-hospital and out of hospital mortality in our administrative database.(100) Finally, we are measuring 25(OH)D at the etiologically relevant time point.

Our data demonstrate that 25(OH)D deficiency at critical care initiation is present and is strongly associated with a significantly increased risk of death, and that this risk is independent of other comorbidities. We believe that our results provide a link between vitamin D at the time of critical care initiation and outcomes in the critically ill. Interpreted together with our prior study of 25(OH)D measured within a year prior to hospital admission,(13) the current study of 25(OH)D measured at critical care initiation strongly supports the importance of vitamin D sufficiency in critical illness. The administration of high doses of oral 25(OH)D can correct vitamin D deficiency in critically ill patients,(104) but further studies are needed to determine if vitamin D supplementation can improve morbidity or mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of our dear friend and colleague Nathan Edward Hellman, MD, PhD. We express deep appreciation to Steven M. Brunelli, MD, MSCE for statistical expertise.

Financial Support: Dr. Christopher is supported by NIH K08AI060881.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Andrea B. Braun, Renal Division, Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Fiona K. Gibbons, Pulmonary Division, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Augusto A. Litonjua, Pulmonary and Critical Care Division, Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Edward Giovannucci, Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health.

Kenneth B. Christopher, The Nathan E. Hellman Memorial Laboratory, Renal Division, Brigham and Women's Hospital.

References

- 1.Fraser DR. Regulation of the metabolism of vitamin D. Physiol Rev. 1980;60:551–613. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1980.60.2.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raiten DJ, Picciano MF. Vitamin D and health in the 21st century: bone and beyond. Executive summary. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1673S–1677S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1673S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick MF. Vitamin D: importance in the prevention of cancers, type 1 diabetes, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:362–371. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teegarden D, Donkin SS. Vitamin D: emerging new roles in insulin sensitivity. Nutr Res Rev. 2009;22:82–92. doi: 10.1017/S0954422409389301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee P, Eisman JA, Center JR. Vitamin D deficiency in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1912–1914. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0809996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van den Berghe G, Weekers F, Baxter RC, et al. Five-day pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone administration unveils combined hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal defects underlying profound hypoandrogenism in men with prolonged critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3217–3226. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Reactivation of pituitary hormone release and metabolic improvement by infusion of growth hormone-releasing peptide and thyrotropin-releasing hormone in patients with protracted critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1311–1323. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.4.5636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van den Berghe G, Baxter RC, Weekers F, et al. The combined administration of GH-releasing peptide-2 (GHRP-2), TRH and GnRH to men with prolonged critical illness evokes superior endocrine and metabolic effects compared to treatment with GHRP-2 alone. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;56:655–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nierman DM, Mechanick JI. Biochemical response to treatment of bone hyperresorption in chronically critically ill patients. Chest. 2000;118:761–766. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeng L, Yamshchikov AV, Judd SE, et al. Alterations in vitamin D status and anti-microbial peptide levels in patients in the intensive care unit with sepsis. J Transl Med. 2009;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun A, Chang D, Mahadevappa K, et al. Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and mortality in the critically ill*. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:671–677. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206ccdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:582S–586S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.582S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman AW. From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:491S–499S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.491S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nalichowski R, Keogh D, Chueh HC, et al. Calculating the benefits of a Research Patient Data Repository. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:1044. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beier K, Eppanapally S, Bazick HS, et al. Elevation of blood urea nitrogen is predictive of long-term mortality in critically ill patients independent of "normal" creatinine. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:305–313. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ffe22a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waikar SS, Mount DB, Curhan GC. Mortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2009;122:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes for Acute Renal Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1688–1694. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bureau of the Census. Census summary tape, file 3A (STF 3A) Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:471–482. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:312–323. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.032482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nandi A, Glass TA, Cole SR, et al. Neighborhood poverty and injection cessation in a sample of injection drug users. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:391–398. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, et al. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polednak AP. Stage at diagnosis of prostate cancer in Connecticut by poverty and race. Ethn Dis. 1997;7:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ensminger ME, Lamkin RP, Jacobson N. School leaving: a longitudinal perspective including neighborhood effects. Child Dev. 1996;67:2400–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McWhorter WP, Schatzkin AG, Horm JW, et al. Contribution of socioeconomic status to black/white differences in cancer incidence. Cancer. 1989;63:982–987. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890301)63:5<982::aid-cncr2820630533>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breen N, Figueroa JB. Stage of breast and cervical cancer diagnosis in disadvantaged neighborhoods: a prevention policy perspective. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, et al. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures--the public health disparities geocoding project (US) Public Health Rep. 2003;118:240–260. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian SV, Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, et al. Racial disparities in context: a multilevel analysis of neighborhood variations in poverty and excess mortality among black populations in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:260–265. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.034132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Choosing area based socioeconomic measures to monitor social inequalities in low birth weight and childhood lead poisoning: The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:186–199. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieger N, Zierler S, Hogan J, et al. Geocoding and Measurement of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Position: A US Perspective. In: Kawachi I, Berkman L, editors. Neighborhoods and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson W. The truly disadvantaged. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saunders MR, Cagney KA, Ross LF, et al. Neighborhood poverty, racial composition and renal transplant waitlist. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1912–1917. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Massey D, Denton N. American Apartheid: Segregation and making of the underclass. Cambridge: MA Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapoport J, Gehlbach S, Lemeshow S, et al. Resource utilization among intensive care patients. Managed care vs traditional insurance. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, et al. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:462–468. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, et al. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schisterman EF, Whitcomb BW. Use of the Social Security Administration Death Master File for ascertainment of mortality status. Popul Health Metr. 2004;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman TB, Brown AN. Use of commercial record linkage software and vital statistics to identify patient deaths. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:233–237. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J AM Stat Assn. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss G, Bogdan C, Hentze MW. Pathways for the regulation of macrophage iron metabolism by the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol. 1997;158:420–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai K, Hsu T, Kong C, et al. Is the endogenous peroxyl-radical scavenging capacity of plasma protective in systemic inflammatory disorders in humans? Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:926–933. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeiro Nogueira C, Ramalho A, Lameu E, et al. Serum concentrations of vitamin A and oxidative stress in critically ill patients with sepsis. Nutr Hosp. 2009;24:312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goode HF, Cowley HC, Walker BE, et al. Decreased antioxidant status and increased lipid peroxidation in patients with septic shock and secondary organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:646–651. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199504000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horner RD, Lawler FH, Hainer BL. Relationship between patient race and survival following admission to intensive care among patients of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 1991;26:531–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carthy EP, Yamashita W, Hsu A, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and rat vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Hypertension. 1989;13:954–959. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levin A, Li YC. Vitamin D and its analogues: do they protect against cardiovascular disease in patients with kidney disease? Kidney Int. 2005;68:1973–1981. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deluca HF, Cantorna MT. Vitamin: D its role and uses in immunology. FASEB J. 2001;15:2579–2585. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0433rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gysemans CA, Cardozo AK, Callewaert H, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates expression of chemokines and cytokines in pancreatic islets: implications for prevention of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1956–1964. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holick MF. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:353–373. doi: 10.4065/81.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nesby-O'Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:187–192. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:384–390. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan TY. Vitamin D deficiency and susceptibility to tuberculosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66:476–478. doi: 10.1007/s002230010095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yener E, Coker C, Cura A, et al. Lymphocyte subpopulations in children with vitamin D deficient rickets. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1995;37:500–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1995.tb03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Etten E, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moro JR, Iwata M, von Andriano UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–698. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kankova M, Luini W, Pedrazzoni M, et al. Impairment of cytokine production in mice fed a vitamin D3-deficient diet. Immunology. 1991;73:466–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu PT, Stenger S, Tang DH, et al. Cutting edge: vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is dependent on the induction of cathelicidin. J Immunol. 2007;179:2060–2063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhalla AK, Amento EP, Krane SM. Differential effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human lymphocytes and monocyte/macrophages: inhibition of interleukin-2 and augmentation of interleukin-1 production. Cell Immunol. 1986;98:311–322. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Durr UH, Sudheendra US, Ramamoorthy A. LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1408–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zanetti M. Cathelicidins, multifunctional peptides of the innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:39–48. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meehan MA, Kerman RH, Lemire JM. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances the generation of nonspecific suppressor cells while inhibiting the induction of cytotoxic cells in a human MLR. Cell Immunol. 1992;140:400–409. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gregori S, Giarratana N, Smiroldo S, et al. A 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) analog enhances regulatory T-cells and arrests autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2002;51:1367–1374. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gregori S, Casorati M, Amuchastegui S, et al. Regulatory T cells induced by 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and mycophenolate mofetil treatment mediate transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;167:1945–1953. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kinsey GR, Sharma R, Huang L, et al. Regulatory T cells suppress innate immunity in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1744–1753. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murphy TJ, Ni Choileain N, Zang Y, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control innate immune reactivity after injury. J Immunol. 2005;174:2957–2963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McHugh RS, Shevach EM. The role of suppressor T cells in regulation of immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:693–702. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.129339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Monneret G, Debard AL, Venet F, et al. Marked elevation of human circulating CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in sepsis-induced immunoparalysis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2068–2071. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069345.78884.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mannick JA, Rodrick ML, Lederer JA. The immunologic response to injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moore FA, Sauaia A, Moore EE, et al. Postinjury multiple organ failure: a bimodal phenomenon. J Trauma. 1996;40:501–510. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00001. discussion 510-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goldstein LB. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke: effect of modifier codes. Stroke. 1998;29:1602–1604. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.8.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Iezzoni LI, Burnside S, Sickles L, et al. Coding of acute myocardial infarction. Clinical and policy implications. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:745–751. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee DS, Donovan L, Austin PC, et al. Comparison of coding of heart failure and comorbidities in administrative and clinical data for use in outcomes research. Med Care. 2005;43:182–188. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levy AR, Tamblyn RM, Fitchett D, et al. Coding accuracy of hospital discharge data for elderly survivors of myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:1277–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Winkelmayer WC, Schneeweiss S, Mogun H, et al. Identification of individuals with CKD from Medicare claims data: a validation study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:225–232. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Humphries KH, Rankin JM, Carere RG, et al. Co-morbidity data in outcomes research: are clinical data derived from administrative databases a reliable alternative to chart review? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kieszak SM, Flanders WD, Kosinski AS, et al. A comparison of the Charlson comorbidity index derived from medical record data and administrative billing data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moreno RP, Metnitz PG, Almeida E, et al. SAPS 3--From evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: Development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1345–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sibbald W. Evaluating Critical Care-Using Health Services Research to Improve Quality. In: Vincent J-L, editor. Update in Intensive Care Medicine. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Quach S, Hennessy DA, Faris P, et al. A comparison between the APACHE II and Charlson Index Score for predicting hospital mortality in critically ill patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:129. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Akbari A, Swedko PJ, Clark HD, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease with laboratory reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate and an educational program. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1788–1792. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guessous I, McClellan W, Vupputuri S, et al. Low documentation of chronic kidney disease among high-risk patients in a managed care population: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2009;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hoste EA, Damen J, Vanholder RC, et al. Assessment of renal function in recently admitted critically ill patients with normal serum creatinine. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:747–753. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kern EF, Maney M, Miller DR, et al. Failure of ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:564–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stevens LA, Fares G, Fleming J, et al. Low rates of testing and diagnostic codes usage in a commercial clinical laboratory: evidence for lack of physician awareness of chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2439–2448. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gentile G, Postorino M, Mooring RD, et al. Estimated GFR reporting is not sufficient to allow detection of chronic kidney disease in an Italian regional hospital. BMC Nephrol. 2009;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zager S, Mendu ML, Chang D, et al. Neighborhood Poverty Rate and Mortality in Patients Receiving Critical Care in the Academic Medical Center Setting. Chest. 2011 doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2594. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gottlieb SS. Dead is dead--artificial definitions are no substitute. Lancet. 1997;349:662–663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)22010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, et al. Cause of death in clinical research: time for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:618–620. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Preen DB, Holman CD, Spilsbury K, et al. Length of comorbidity lookback period affected regression model performance of administrative health data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:940–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mata-Granados JM, Vargas-Vasserot J, Ferreiro-Vera C, et al. Evaluation of vitamin D endocrine system (VDES) status and response to treatment of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) using an on-line SPE-LC-MS/MS method. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.