Abstract

As part of the innate immune response, neutrophils are at the forefront of defence against infection, resolution of inflammation and wound healing. They are the most abundant leucocytes in the peripheral blood, have a short lifespan and an estimated turnover of 1010 to 1011 cells per day. Neutrophils efficiently clear microbial infections by phagocytosis and by oxygen-dependent and oxygen-independent mechanisms. In 2004, a new neutrophil anti-microbial mechanism was described, the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) composed of DNA, histones and anti-microbial peptides. Several microorganisms, bacterial products, as well as pharmacological stimuli such as PMA, were shown to induce NETs. Neutrophils contain relatively few mitochondria, and derive most of their energy from glycolysis. In this scenario we aimed to analyse some of the metabolic requirements for NET formation. Here it is shown that NETs formation is strictly dependent on glucose and to a lesser extent on glutamine, that Glut-1, glucose uptake, and glycolysis rate increase upon PMA stimulation, and that NET formation is inhibited by the glycolysis inhibitor, 2-deoxy-glucose, and to a lesser extent by the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin. Moreover, when neutrophils were exposed to PMA in glucose-free medium for 3 hr, they lost their characteristic polymorphic nuclei but did not release NETs. However, if glucose (but not pyruvate) was added at this time, NET release took place within minutes, suggesting that NET formation could be metabolically divided into two phases; the first, independent from exogenous glucose (chromatin decondensation) and, the second (NET release), strictly dependent on exogenous glucose and glycolysis.

Keywords: ATP synthase, cell metabolism, glycolysis, neutrophil extracellular traps, neutrophils

Introduction

Neutrophils are short-lived cells of the innate immune system that mature in the bone marrow, acquiring the ability to phagocytose and kill microorganisms.1–3 Recently, neutrophils have also been implicated in immune regulation.4–6 Mature neutrophils are released from the bone marrow into the bloodstream where they are thought to last for up to 24 hr. However, if they migrate into tissues, they may remain functional for at least two additional days, after which they undergo apoptosis and are cleared by macrophages or dendritic cells, or they return to the bone marrow as senescent cells.1,7,8 New data show that the half-life of neutrophils in circulation is about 5 days.6,9 In any event, such a short lifespan is compensated by a high turnover rate estimated to be in the order of 1010 to 1011 neutrophils being replaced every day.10,11

Neutrophils are the first cells to be attracted to infected or sterile wounded tissues where, in addition to providing immune protection, they may also contribute to healing and recovery.12,13 Neutrophils kill bacteria by engulfment and formation of phagosomes, which fuse with lysosomes to create phagolysosomes where microbes are killed by oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms, such as enzymes that catalyse the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and the release of proteases, iron-binding proteins and defensins.13,14

In 2004, a new functional capacity of neutrophils was identified, the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), composed of DNA, histones and microbicidal peptides, with the ability to kill some bacterial species.15 Several studies have addressed the possible mechanisms that account for NETs formation. It has been shown that PKC-mediated activation of the Raf-Mek-Erk signalling pathway,16 hyper-citrullination of histones,3,17–20 and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)21 are required for this process to take place.

Over the last decade, there has been a renewed interest in the analysis of the metabolic basis of immune function, and new physiological links and potential immunoregulatory pathways have been uncovered.22–25 In the present work, we sought to investigate some of the metabolic requirements for NET formation.

From the metabolic point of view, it is known that neutrophils contain fewer and less active mitochondria than other immune cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages,26,27 and that they derive their energy mainly from glycolysis.28,29

Our results, obtained by using conditioned culture media and metabolic inhibitors, suggest that NET formation can be divided into two distinguishable metabolic phases, the latest (NET release) being strictly dependent on exogenous glucose and glycolysis, so opening the possibility for metabolism-based regulation of neutrophil function.

Materials and methods

Neutrophil isolation

Neutrophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors (female and male between 20 and 28 years old) using heparin as anti-coagulant and gradient centrifugation on Polymorphprep™ (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) (volume/volume, 300 g for 50 min at 25°). The polymorphonuclear cell-containing interface was recovered and washed twice with PBS pH 7·2 (300 g for 5 min at 4°). Neutrophils were counted, suspended in the indicated culture medium and used immediately. This protocol was reviewed by the Institutional (ENCB-IPN) Bioethics Committee. The purity of neutrophil preparations was assessed on the basis of size, granularity and CD16 expression, whereby cells (1 × 106) were labelled with 1 μg/ml rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-human CD16 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) for 30 min at 4° followed by a washing step with PBS and further labelling with 1 μg/ml polyclonal FITC-donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) for 30 min at 4°. After the last washing with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and analysed by flow cytometry (FACScalibur; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Results are expressed as the percentage of CD16+ cells.

NET formation (fluorescence microscopy)

Neutrophils (3 × 105) were seeded on 16-well Lab-Tek tissue culture chambers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Walthman, MA), in RPMI-1640 culture media (In Vitro SA, Mexico City, Mexico) specifically formulated with either glucose and glutamine, glutamine and no glucose, glucose and no glutamine, or no glucose and no glutamine (conditioned media). Neutrophils were stimulated with either 10, 50 or 100 nm PMA (Sigma, St Louis, MO) or with 1 μm N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenyl alanine (fMLP) (Sigma) for 3 hr. In another set of experiments, cells were stimulated with 100 nm PMA, and incubated at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1 to 5 hr and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed twice with PBS and stained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) or with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against H3 histone (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The cell preparations were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Labs, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and analysed in an Eclipse E800 fluorescent microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY).

In additional experiments, neutrophils were cultured in glucose-free and glutamine-free RPMI-1640 media, stimulated with PMA (100 nm) for 3 hr and then supplemented with glucose (4 mm) or pyruvate (2 mm), fixed at 2 and 10 min after glucose or pyruvate addition and then prepared for fluorescent- or electron-microscopy, as indicated.

NET formation (scanning electron microscopy)

Neutrophils (5 × 104) were seeded on glass coverslips (13 mm diameter) in 24-well culture plates, in each of the several conditioned media previously mentioned, or in the presence or absence of the metabolic inhibitors, as indicated. Neutrophils were then left untreated or stimulated with PMA (100 nm), and cultured for 3 hr at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, after which they were fixed with 2·5% glutaraldehyde for 1 hr and then washed three times with Sorensen PBS. Cells were post-fixed with 1% OsO4 for 1 hr and then further washed (three times) with Sorensen PBS. Samples were dehydrated, by using graded ethanol concentrations, from 30% to absolute ethanol, for 10 min each, plus two additional immersions in absolute ethanol, for 10 min each. The glass coverslips were dried to the critical point and covered with gold. The samples were analysed in a JEOL JEM5800LUV scanning electron microscope (JEOL Inc., Peabody, MA).

Pharmacological inhibition of glycolysis and ATP synthase

Neutrophils (3 × 105) were seeded on 16-well Lab-Tek tissue culture chambers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), in RPMI-1640 culture media formulated with glucose (4 mm) and glutamine (2 mm) and then supplemented with either 2 mm 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) or 10 μg/ml oligomycin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.,) to inhibit glycolysis or ATP synthase, respectively. After 15 min at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, PMA was added (100 nm), and the cells were further incubated for 3 hr and then treated, as previously indicated, for fluorescent microscopy or electron microscopy analyses.

Glut-1 expression

After the indicated treatments, neutrophils were incubated with DyLight 650-labelled rabbit anti-Glut-1 polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) for 30 min at 4°. After washing, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Expression of Glut-1 on the neutrophil cell membrane was assessed by flow cytometry (FACS Aria III; BD Biosciences). Raw data were analysed by FlowJo 8·7 software (facs software; Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Mean fluorescence intensity numerical values were normalized to express results as PMA-induced fold-change of Glut-1 expression over basal levels (non-stimulated cells) at each time-point.

Glucose uptake assay

Neutrophils (1 × 106) cultured in serum-free RPMI in siliconized glass tubes were supplemented with the fluorescent glucose analogue 2-(N-(7-nitrobenzen-2-oxa-1, 3-diazol-4-yl) amino)-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), at a final concentration of 250 μm. Then neutrophils were left untreated or activated with PMA, and then incubated at 37° for 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, or 120 min; next, they were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS before flow cytometry analysis. Raw data were analysed with FlowJo 8·7 software (facs software, Tree Star, Inc.). The level of emitted fluorescence is indicative of glucose uptake.

Glycolysis assay (lactate production)

Cell-free supernatants from non-stimulated or PMA-stimulated neutrophils cultured in serum-free RPMI-1640, were harvested at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 hr, and analysed for lactate content using a lactate assay kit (Abcam). Briefly, 10 μl of each supernatant sample or lactate concentration standards was incubated with 100 μl of lactate reagent solution for 10 min, after which the absorbance was measured at 540 nm in an ELISA plate reader (Labsystems Diagnostics, Vantaa, Finland). The resulting optical density (OD) data were transformed into lactate concentration by means of a standard lactate curve. The glycolytic rate was calculated by dividing the lactate concentration at a time-point by the lactate concentration in the previous time-point, and expressed as the fold-change of lactate production. Finally, the slope of lactate accumulation was compared between non-stimulated and PMA-activated neutrophils.

Reactive oxygen species production

The production of intracellular ROS by non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils was measured using the ROS-specific probe 5- (and-6)-chloromethyl-2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and flow cytometry. Neutrophils (1 × 106) were suspended in 500 μl of PBS and then labelled with 20 μm CM-H2DCFDA for 20 min at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Neutrophils were washed with PBS and suspended in the indicated culture media and incubated at 37°. At the indicated times, samples were analysed by flow cytometry (FACScalibur; BD Bioscience) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 525 nm. Raw data were analysed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Quantification of NETs

Non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils were stained with DAPI, and fluorescent microscopy images of the cells were analysed with ImageJ software, (NIH, Bethesda, MD) as described by Papayannopoulos et al.30 Briefly, DAPI signal (cell DNA) area was delineated for each individual cell (200 cells per condition). The mean DNA area was obtained from three independent experiments and compared between the different experimental conditions. DNA area is indicative of the formation of NETs. Results are represented as cell area (arbitrary units).

Assessment of chromatin decondensation

In addition to DAPI staining, chromatin decondensation was further assessed by two different approaches. First, by using the Nuclear-ID™ Green chromatin condensation detection kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), whereby 1 × 106 neutrophils per condition (complete medium, glucose-free and glutamine-free medium, with or without PMA for 3 hr) were stained following the manufacturer′s instructions. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min, the cell pellet was then re-suspended in 200 μl of freshly prepared assay buffer (provided in the kit) containing the Nuclear-ID™ Green detection reagent at a final concentration of 2 μm, cells were incubated for 30 min at 4° and then fixed by adding 200 μl of 4% paraformaldehyde for analysis by flow cytometry (FACScan; BD Biosciences) and CellQuest software (FACScan; BD Biosciences). Results are expressed as the percentage of cells with low mean fluorescence intensity, as indicative of cells that have undergone chromatin decondensation.

Second, neutrophils treated as previously indicated, were prepared for transmission electron microscopy as follows: cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 2·5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) in PBS, washed three times with PBS, and post-fixed with 1% OsO4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 2 hr at 4°. Samples were dehydrated with absolute ethanol (J.T. Baker, Xalostoc, Mexico), embedded in EPON 812 resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and subjected to 60° for 24 hr. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were obtained with a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), contrasted with uranyl acetate (Sigma) and Reynold's lead citrate, and observed with a Jeol JEM1010 electron transmission microscope (JEOL, Akishima-SHI, Japan), operated at 60 kV.

Statistical analyses

The fold change of Glut-1 expression and glucose uptake was analysed by a two-way analysis of variance with the normalized data from the mean fluorescence intensity. Glycolysis rate was analysed by means of linear regression and slope assessment, and quantification of NETs, chromatin decondensation, and ROS production were analysed by one-way analysis of variance. Analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism Software (La Jolla, CA). Statistical differences were set at P < 0·05.

Results

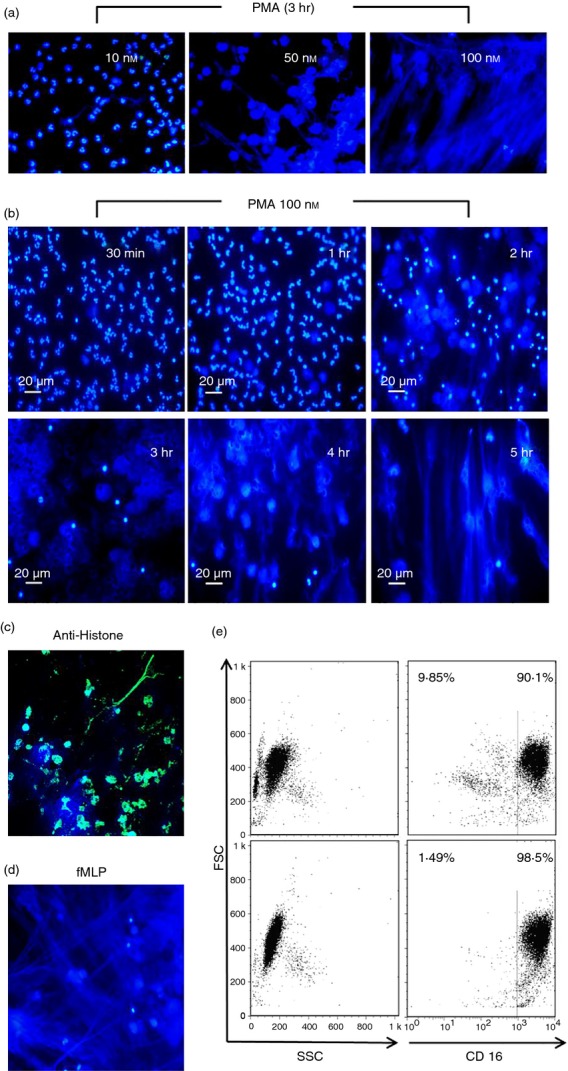

PMA induces NETs formation

Several microorganisms have been shown to induce NETs formation3,31 and PMA has been described as one of the best pharmacological inducers of NETs.32 PMA dose–response assays were carried out with 10, 50 and 100 nm. On the basis of our results, PMA at a final concentration of 100 nm was used as an in vitro model of NET formation to be used in all further metabolic studies (Fig.1a). Figure1(b) shows representative kinetics of NET formation up to 5 hr post-PMA stimulation in DAPI-stained neutrophils. In addition to DNA, NETs also contain elastase, and histones, among several other proteins.33 So, PMA-stimulated neutrophils were also labelled with anti-H3 histone antibody to corroborate the formation of NETs. Figure1(c) shows that the structures released by neutrophils in addition to DNA also contain histones and therefore are NETs. As an additional control we used another well-characterized inducer of NETs (fMLP) at 1 μm (Fig.1d). Figure1(e) shows a representative flow cytometry analysis of total peripheral blood cells (upper panels) versus polymorphprep-enriched neutrophils (lower panels), as assessed by forward scatter, side scatter and CD16+ cells.

Figure 1.

Dose–response and kinetics of PMA-induced neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. (a) Polymorphprep-enriched neutrophils were stimulated with PMA (10, 50 and 100 nm) fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, washed with PBS, treated with DAPI for DNA staining, and then analysed by fluorescence microscopy (formation of NETs). (b) Neutrophils were activated with 100 nm PMA and then at the indicated times post-PMA (30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 hr) analysed for the formation of NETs, Bar = 20 μm. (c) Neutrophils stimulated with PMA (100 nm) for 3 hr were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained for histones. (d) Neutrophils were stimulated with 1 μm fMLP, as an additional control of NET formation. (e) Flow cytometry-based assessment of neutrophil enrichment by polymorphprep on the basis of forward and side scatter and CD16+ cells. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

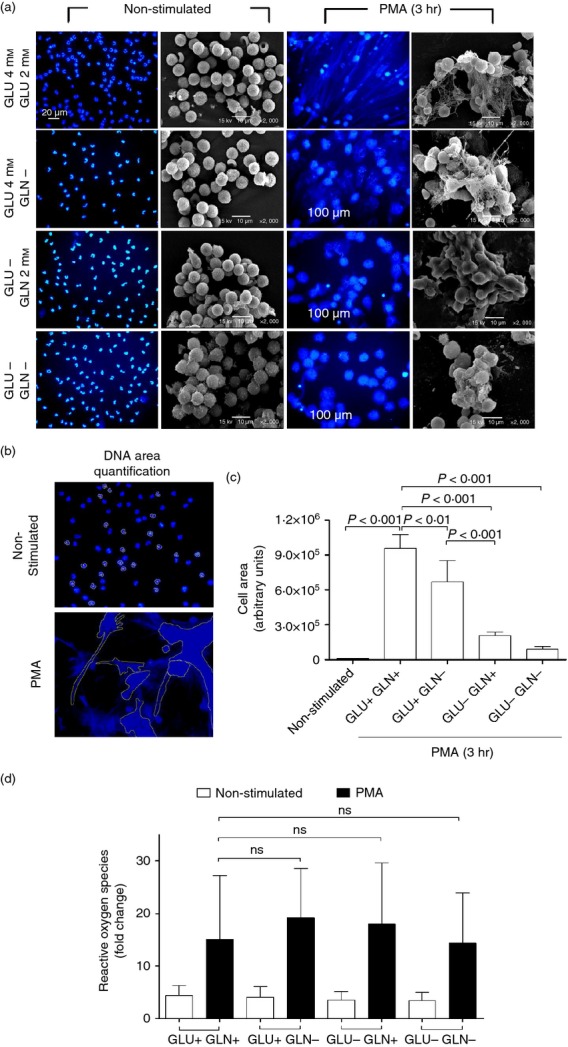

NET formation is dependent on glucose and, to a lesser extent, on glutamine

As a first approach to analyse the metabolic requirements for NET formation, several conditioned culture media were used, i.e. glutamine-free, glucose-free, and glucose- and glutamine-free RPMI-1640, along with complete media (glucose and glutamine), as positive control. As NETs formation was evident 3 hr after PMA stimulation in most cells, as shown in Fig.1, the rest of the experiments were carried out at this time-point of the process. Figure2(a) shows fluorescent images and scanning electron microscopy images of non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils at 3 hr post-PMA addition in each conditioned culture medium. As shown, NET formation was dependent on glucose. On the other hand, the absence of glutamine diminished but did not completely inhibit the formation of NETs. As a way to quantify the extent of inhibition in the formation of NETs under the different culture conditions, fluorescence microscopy images were analysed to determine the DNA area, using ImageJ software, as described elsewhere.30 Figure2(b) shows a representative picture of how images were analysed and Fig.2(c) shows the calculated DNA area (arbitrary units) ± SD for each condition. A larger area means the formation of more NETs.

Figure 2.

Dose–response and kinetics the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. (a) Isolated neutrophils were cultured in specific formulated media (conditioned media), containing: glucose and glutamine, glucose but no glutamine, glutamine but no glucose, or no glucose and no glutamine. Cells were left untreated or stimulated with PMA (100 nm) for 3 hr; thereafter, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, washed with PBS, and stained for DNA with DAPI. (b and c) DNA area quantification was performed from fluorescence microscopy images using ImageJ software, to quantify the formation of NETs, as described in the Materials and methods. (d) ROS production was determined by CM-H2DCFDA in non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils, cultured in the different conditioned media as shown. Results are from three independent experiments. Raw data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance.

As the formation of NETs is ROS-dependent,21 the production of ROS was assessed in non-stimulated and PMA-simulated neutrophils cultured for 1 hr in the different conditioned media, as described (Fig.1d). For comparison, base level of ROS (non-stimulated neutrophils at time 0) was given a value of 1, and the fold change of ROS production for all other conditions was then calculated.

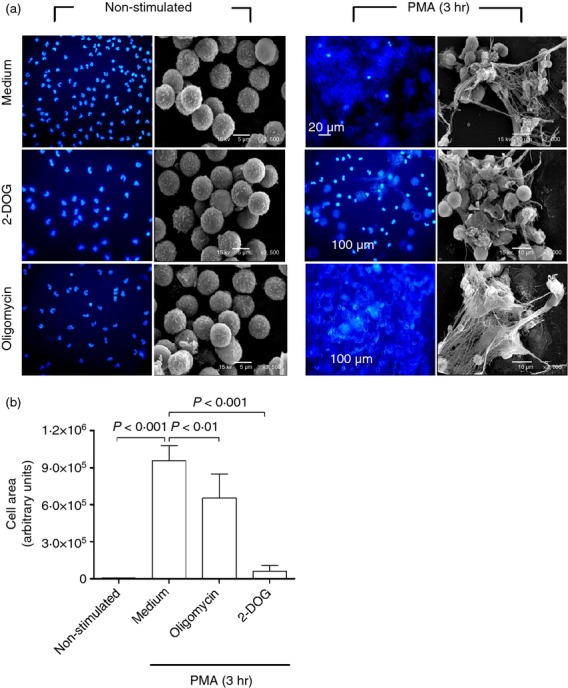

The formation of NETs is dependent on glycolysis and to a lesser extent on ATP synthase

After showing that the formation of NETs is dependent on the presence of glucose in the culture media, we questioned how this additional glucose is metabolized. To answer this question, neutrophils were stimulated with PMA for 3 hr in the presence of 2-DOG (a glycolysis inhibitor) or oligomycin (an ATP synthase inhibitor). Figure3(a) shows that oligomycin had little to no effect, whereas 2-DOG inhibited the formation of NETs almost completely, suggesting that this is a glycolysis-dependent process in which mitochondrially generated ATP (oxidative phosphorylation) is not required. However, when the formation of NETs was quantified by ImageJ analysis (Fig.3b), the results showed that oligomycin, although to a lesser extent than 2-DOG, also inhibited the formation of NETs.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological inhibition of glycolysis and to a lesser extent of ATP synthase inhibits the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). (a) Isolated neutrophils were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium, incubated with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG; a glycolysis inhibitor), with oligomycin (an ATP synthase inhibitor), or medium alone for 15 min at 37°. Thereafter, a set of cells was left untreated (non-stimulated) and another set of cells was stimulated with 100 nm PMA. After 3 hr at 37°, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, washed with PBS and stained for DNA with DAPI for fluorescence microscopy, or fixed with 2·5% glutaraldehyde and treated for scanning electron microscopy. Images are representative of multiple microscopic fields from three independent experiments. (b) Quantification of NET formation (DNA area) using ImageJ software. Data obtained from ImageJ were analysed by one-way analysis of variance.

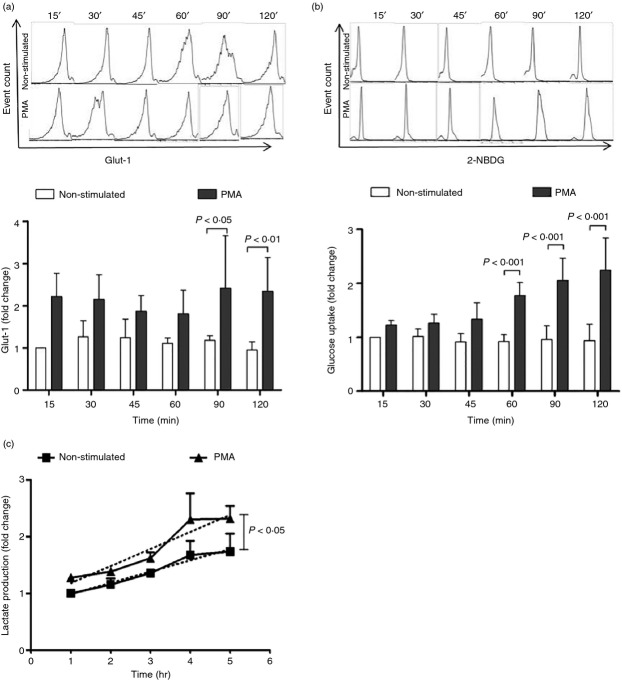

PMA stimulation increases the amount of Glut-1 on the cell membrane of neutrophils

The formation of NETs requires glucose in the culture medium, which is then metabolized mainly by glycolysis but also by oxidative phosphorylation (as shown by the use of 2-DOG and oligomycin). Transporters are essential to enable glucose to enter the cell. Short-lived Glut-1 is one of the glucose transporters that have been found in neutrophils,34 hence the relative amount of Glut-1 on the neutrophil cell membrane was assessed by flow cytometry, in both non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils at different time-points. Figure4(a) shows a representative set of flow cytometry raw data, and the normalized values of Glut-1 content. The amount of Glut-1 seemed to be higher in PMA-stimulated than in non-stimulated neutrophils at all time-points tested after the addition of PMA. However, this trait was statistically significant (P < 0·01) only at 90 and 120 min after PMA stimulation.

Figure 4.

PMA stimulation of neutrophils increases Glut-1 cell membrane expression, glucose uptake and glycolysis rate. (a) Glut-1 expression was analysed by staining neutrophils with an anti-Glut-1 fluorochrome-labelled monoclonal antibody and flow cytometry, the upper panels depict a representative set of flow cytometry data and the lower panel depicts the normalized data of Glut-1 cell membrane expression from three independent experiments. (b) Glucose uptake was assessed by the uptake of the fluorescent glucose analogue 2-NBDG and flow cytometry. The upper panels depict a representative set of flow cytometry data, and the lower panel depicts the fold change of glucose uptake, from 15 to 120 min by non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils, as compared with the glucose uptake by non-stimulated neutrophils at 15 min (with a given value of 1). (c) Glycolytic rate was assessed by measuring the lactate production in the supernatant of cultured neutrophils and dividing the amount of lactate at one time-point by that in the previous time-point. Glycolytic rate is expressed as the fold change in lactate production. Depicted is the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Discontinued lines represent linear regression and the slope for each line. Differences in slopes and, therefore, in glycolytic rate were statistically significant (P < 0·05).

PMA stimulation increases neutrophils glucose uptake

Glucose uptake was evaluated by means of a fluorescent glucose analogue (2-NBDG) and flow cytometry. Figure4(b) shows a representative experiment of 2-NBDG uptake by both non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils at different time-points, up to 120 min, and the normalized data, expressed as the fold change. 2-NBDG uptake significantly increased from the first hour after PMA addition. In contrast, 2-NBDG was not taken up by non-stimulated neutrophils.

PMA stimulation increases the glycolytic rate in neutrophils

Neutrophils (2 × 106) were cultured in medium alone or stimulated with PMA in 12-well culture plates. Supernatants from both cell culture conditions were harvested at the indicated time-points. The amount of lactate in those supernatants was measured by means of a colorimetric lactate kit (Abcam). Optical density data were transformed into amount of lactate (ng/ml) using a lactate standard curve. The glycolytic rate was calculated by dividing the amount of lactate at a given time by the amount of lactate in the previous time-point. Figure4(c) shows the glycolytic rate for non-stimulated and for PMA-stimulated neutrophils. The slope of both lines shows a statistically significant (P < 0·05) increase in the glycolytic rate of PMA-stimulated neutrophils, as compared with non-stimulated neutrophils.

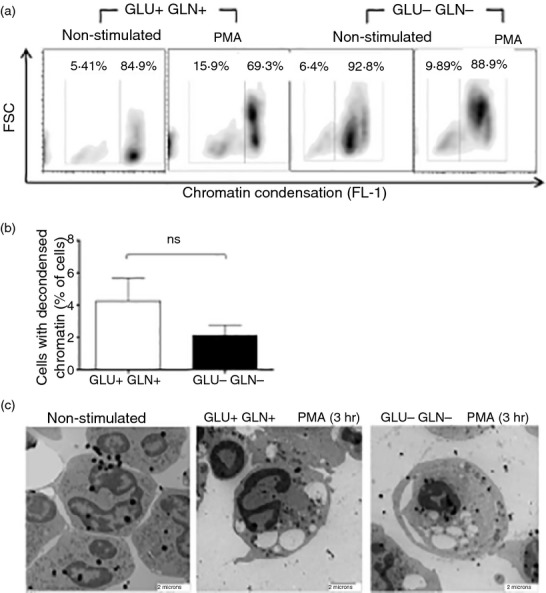

Identification of two metabolically distinguishable phases in the formation of NETs

The experiments with glucose-free medium showed that upon PMA stimulation, neutrophils lost their characteristic nuclei structure (multiple lobules), becoming more diffuse and occupying most of the cytoplasm but did not release NETs (Fig.2), suggesting that chromatin decondensation had taken place. To further explore this finding, treated neutrophils (medium alone versus PMA; and glucose- and glutamine-containing versus glucose- and glutamine-free medium) were stained with the Nuclear-ID™ Green chromatin detection kit (Enzo Life Sciences). Figure5(a) shows a representative density plot of cell size (forward scatter) versus chromatin condensation, and Fig.5(b) shows the integrated results from five independent experiments. The percentage of neutrophils with decondensed chromatin increases upon PMA stimulation regardless of the culture medium used, and no significant difference was observed. In addition, neutrophils under the same culture conditions, as described, were analysed by transmission electron microscopy. Figure5(c) shows condensed chromatin in the non-stimulated neutrophils and diffuse nuclei and decondensed chromatin in the PMA-stimulated neutrophils, regardless of the presence or absence of glucose and glutamine in the culture medium. Together, these findings corroborate that in the absence of glucose and glutamine, chromatin decondensation can take place in neutrophils upon PMA activation.

Figure 5.

PMA activation of neutrophils, even in the absence of glucose and glutamine, induces chromatin decondensation. Neutrophils (1 × 106) in glucose- and glutamine-containing medium or in glucose- and glutamine-free medium were cultured for 3 hr with or without 100 nm PMA, after which, (a) chromatin condensation was assessed using the Nuclear-ID™ Green chromatin condensation detection kit and flow cytometry, results are expressed as the percentage of neutrophils with decondensed chromatin, and (b) as the fold change (non-stimulated versus PMA) in the percentage of neutrophils with decondensed chromatin for the two culture conditions. Results are from five independent experiments. Data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance. (c) Neutrophils were prepared for transmission electron microscopy as described in the Materials and methods, images are representative from multiple microscopic fields from two independent experiments.

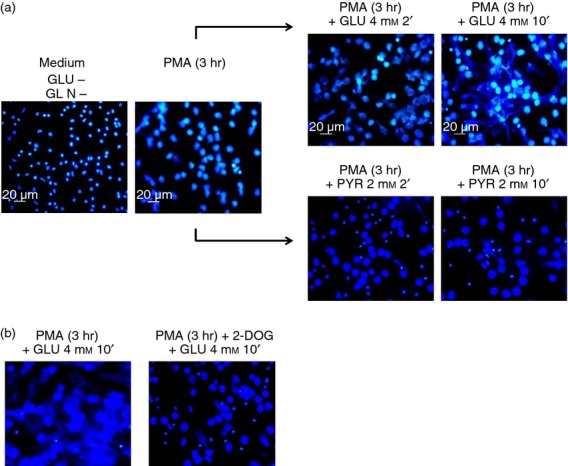

We then wondered what would happen if neutrophils were stimulated with PMA in glucose- and glutamine-free medium for 3 hr, and then glucose was added. Would neutrophils be able to release NETs under these conditions? Such experiments were performed and, in another set of experiments, pyruvate instead of glucose was added.

Figure6(a) shows that the addition of glucose to neutrophils previously activated with PMA in glucose-free medium, for 3 hr, allows for the release of NETs as rapidly as 10 min thereafter. In contrast, when pyruvate instead of glucose was added, no release of NETs was observed, suggesting that an early phase of PMA-induced NET formation, lasting 2–3 hr, can take place in the absence of exogenous glucose (chromatin decondensation), whereas a second phase (NETs release), lasting only a few minutes, is dependent on exogenous glucose and glycolysis. Additional experiments were performed in which neutrophils were stimulated with PMA in glucose- and glutamine-free medium for 3 hr and then, cell cultures were supplemented with 2 mm of 2-DOG 10 min before the addition of 4 mm glucose. Figure6(b) shows that the addition of exogenous glucose to neutrophils at the later stages of PMA activation does not induce the release of NETs if glycolysis has previously been inhibited. These findings demonstrate that the last stage for the release of NETs requires both exogenous glucose and a functional glycolytic pathway.

Figure 6.

Addition of glucose and to a lesser extent of pyruvate to PMA-stimulated neutrophils in glucose-free medium induces a rapid release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). (a) Neutrophils were suspended in glucose- and glutamine-free medium and then stimulated with PMA (100 nm) for 3 hr at 37°. After this time, when no evident release of NETs was observed, 4 mm glucose or 2 mm pyruvate was added. A set of cells was fixed after 2 min, and another set of cells was fixed after 10 min of glucose or pyruvate addition, with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, washed with PBS and then treated with DAPI for DNA staining. Cell preparations were analysed by fluorescence microscopy. Images are representative of multiple microscopic fields from three independent experiments. (b) To test if the release of NETs upon glucose addition to pre-activated neutrophils in glucose-free medium is due to glycolysis, the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG) was added before glucose.

Discussion

Neutrophil extracellular traps have been proposed to play a protective15,35 as well as a pathogenic16,36 role. Obtaining insight into the mechanisms that secure the release of NETs would help to better understand the physiological conditions under which neutrophils exert those opposite roles. In this regard, it is known that some reactive oxygen species,21 the Raf-Mek-Erk signalling pathway,37 and the hyper-citrullination of histones,3,17–19,38 are required for the formation of NETs. In this work, we sought to investigate some of the metabolic requirements for this process to take place.

Neutrophils are regarded as the first line of defence against infection; they are the most abundant leucocytes in the human blood, are short lived, have a high turnover rate, are able to function in an inflammatory environment, where oxygen tension is usually low, and have potent anti-microbial properties, including NETs release.15,28,39,40 Taking all this into account, PMA-induced NET formation (Fig.1) was used as a model system to analyse some of the metabolic traits of activated neutrophils.

Results showed that the formation of NETs is dependent on glucose and, to a lesser extent, on glutamine (Fig.2). This would be expected because glucose is one of the main metabolic substrates and the principal energy source of neutrophils,41 whereas glutamine accounts for > 20% of the free amino acid pool in plasma,42,43 and both have metabolically overlapping functions such as NADPH production and redox homeostasis.44 In addition, glutamine supports glutathione biosynthesis, whose absence favours oxidative damage in some cell types.44–46 The production of ROS, as a requirement for the formation of NETs21 was confirmed (Fig.2d).

To analyse how glucose is used, an inhibitor of glycolysis (2-DOG) and an inhibitor of ATP synthase (oligomycin) were used; 2-DOG almost completely inhibited the formation of NETs whereas oligomycin did so but to a lesser extent, suggesting that glycolysis was more relevant than mitochondrially generated ATP for this process (Fig.3). The relative amount of Glut-1 on the cell membrane of neutrophils, glucose uptake and the glycolytic rate (lactate production) were assessed in non-stimulated, as well as in PMA-stimulated neutrophils, at different time-points up to 5 hr. Figure4 shows that all three parameters were higher in PMA-stimulated than in non-stimulated neutrophils. Glut-1 expression in neutrophils was variable among individuals, and although there was an apparent increase in Glut-1 expression at early time-points following PMA activation, this increase was only statistically significant at the latest times tested (90 and 120 min) (Fig.4a). Glucose (2-NBDG) uptake was accumulative and differences between non-stimulated and PMA-stimulated neutrophils were also more evident at later time-points (Fig.4b). The glycolysis rate was also higher in PMA-stimulated neutrophils than in non-stimulated neutrophils (Fig.4c), a result that is in keeping with the observed inhibition of NET formation when the glycolysis inhibitor 2-DOG was present in the culture medium (Fig.3).

Non-stimulated neutrophils maintained for up to 3 hr in glucose-free or glucose-free and glutamine-free culture media did not show any morphological alterations indicative of cell damage or cell death (Fig.2). Cell viability (> 95%) was confirmed by trypan blue exclusion (data not shown). This is relevant because it has been shown that glucose but not glutamine protects neutrophils against spontaneous apoptosis when cultured for 24 hr or more.40

Fluorescent microscopy analyses showed that in the absence of glucose or in the presence of a glycolysis inhibitor (2-DOG), PMA-stimulated neutrophils were unable to release NETs. However, it was also observed that these cells lost their characteristic nuclear morphology, resembling cells at earlier stages of NET formation or, chromatin decondensation (Figs2 and 3). In this regard, chromatin decondensation was corroborated by two additional methods, as shown in Fig.5. Thereafter, neutrophils cultured in glucose- and glutamine-free medium were stimulated with PMA for 3 hr and, then, glucose (4 mm final concentration) or pyruvate (2 mm final concentration) was added. Figure6 shows that under these conditions the release of NETs takes place within 10 min of glucose addition, confirming the dependence on exogenous glucose in this process, as previously shown (Fig.2). In contrast, the addition of pyruvate had no visible effect. In other cell types, such as activated lymphocytes, pyruvate enters the cell and is incorporated into the tricarboxylic acid cycle, via its conversion to oxaloacetate (by pyruvate carboxylase) or to acetyl coenzyme A (by pyruvate dehydrogenase), so contributing to mitochondrial ATP synthesis.47 This last finding explains in part, why inhibition of ATP synthase had a smaller effect on NET formation than inhibition of glycolysis, and shows that neutrophils do not rely on mitochondrial function for the release of NETs, even under experimental conditions in which glycolysis is bypassed.

Taken together, the results here presented provide evidence on the strict dependence on glucose and glycolysis for NETs formation. In addition, results show that the formation of NETs can be divided into two distinguishable metabolic phases; an early one, not strictly dependent on exogenous glucose that takes place within a few hours (chromatin decondensation), and a later one, strictly dependent on exogenous glucose that takes place within minutes (NETs release).

There is growing evidence of cross-talk between metabolism and immune response both at the cellular and at the systemic levels,22–25 raising the possibility for metabolism-based immune regulation.23,47,48

Whether NETs formation could be metabolically turned on and off within specific clinical settings remains to be analysed, the findings presented here open such a possibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers who kindly contributed to improve this work. This work was financed in part by SIP-IPN (20140282) and CONACYT (CB-2010-01-158340) grants. O. Rodríguez-Espinosa was the recipient of CONACYT scholarships. O. Rojas-Espinosa, MMBMA, EOLV and FJSG are COFAA/EDI/SNI fellows.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Bainton DF, Ullyot JL, Far-quhar MG. The development of neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes in human bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1971;134:907–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser L, Fiederlein RL. Functional differentiation of normal human neutrophils. Blood. 1987;69:937–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Kobayashi SD, Quinn MT, DeLeo FR. A NET outcome. Front Immunol. 2012;3:365. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay J, Kamp VM, van Hoffen E, et al. A subset of neutrophils in human systemic inflammation inhibits T cell responses through Mac-1. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:327–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI57990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puga I, Cols M, Barra CM, et al. B cell-helper neutrophils stimulate the diversification and production of immunoglobulin in the marginal zone of the spleen. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:170–80. doi: 10.1038/ni.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak T, Tesselaar K, Pillay J, Borghans JA, Koenderman L. What's your age again? Determination of human neutrophil half-lives revisited. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:595–601. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill JS, Henson PM, Haslett C. Phagocytosis of aged human neutrophils by macrophages is mediated by a novel “charge-sensitive” recognition mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1518–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI114328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Burdon PC, Bridger G, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Williams TJ, Rankin SM. Chemokines acting via CXCR2 and CXCR4 control the release of neutrophils from the bone marrow and their return following senescence. Immunity. 2003;19:583–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay J, Den Braber I, Vrisekoop N, Kwast LM, De Boer RJ, Borghans JA, Tesselaar K, Koenderman L. In vivo labelling with 2H2O reveals a human neutrophil lifespan of 5.4 days. Blood. 2010;116:625–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-259028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancey JT, Deubelbeiss KA, Harker LA, Finch CA. Neutrophil kinetics in man. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:705–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI108517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin SM. The bone marrow: a site of neutrophil clearance. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:241–51. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0210112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:159–75. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabady RL, McCormick BA. Control of neutrophil inflammation at mucosal surfaces by secreted epithelial products. Front Immunol. 2013;4:220. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–82. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkim A, Fürnrohr BG, Amann K, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9813–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeli I, Dwivedi N, Khan S, Radic M. Regulation of extracellular chromatin release from neutrophils. J Innate Immun. 2009;1:194–201. doi: 10.1159/000206974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Li M, Lindberg M, Kennett M, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1853–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner M, Wang S, Lewis C, Zheng H, Chen XA, Santy L, Wang Y. PAD4 mediated histone hypercitrullination induces heterochromatin decondensation and chromatin unfolding to form neutrophil extracellular trap-like structures. Front Immunol. 2012;3:307. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:205–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner T, Moller S, Klinger M, Solbach W, Laskay T, Behnen M. The impact of various reactive oxygen species on the formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Mediators Inflamm. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/849136. ; Article ID 849136, doi: 10.1155/2012/849136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox CJ, Hammerman PS, Thompson CB. Fuel feeds function: energy metabolism and the T-cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:844–52. doi: 10.1038/nri1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordbar A, Mo ML, Nakayasu ES, et al. Model-driven multi-omic data analysis elucidates metabolic immunomodulators of macrophage activation. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:558. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O′Neill LA, Hardie DG. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudostarvation. Nature. 2013;493:346–55. doi: 10.1038/nature11862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity. 2013;38:633–43. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, Moots RJ, White MR, Edwards SW. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;17:1964–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maianski NA, Geissler J, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Roos D, Kuijpers TW. Functional characterization of mitochondria in neutrophils: a role restricted to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:143–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borregaard N, Herlin T. Energy metabolism of human neutrophils during phagocytosis. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:550–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI110647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raam BJ, Sluiter W, de Wit E, Roos D, Verhoeven AJ, Kuijpers TW. Mitochondrial membrane potential in human neutrophils is maintained by complex III activity in the absence of Supercomplex Organisation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;91:677–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Kichik V, Mondragón-Flores R, Mondragón-Castelán M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2009;89:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V, Goosmann C, Kühn L, Zychlinsky A. Automatic quantification of in vitro NET formation. Front Immunol. 2013;3:413. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban CF, Ermert D, Schmid M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defence against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A, Ahmed N, Berridge M. Acute regulation of glucose transport after activation of human peripheral blood neutrophils by phorbol myristate acetate, fMLP, and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1998;91:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenne CN, Wong CH, Zemp FJ, McDonald B, Rahman MM, Forsyth PA, McFadden G, Kubes P. Neutrophils recruited to sites of infection protect from virus challenge by releasing neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:169–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossaint J, Herter JM, Van Aken H, Napirei M, Döring Y, Weber C, Soehnlein O, Zarbock A. Synchronized integrin engagement and chemokine activation is crucial in neutrophil extracellular trap mediated sterile inflammation. Blood. 2014;123:2573–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-516484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, Waldmann H. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:75–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmers S, Teijaro JR, Arandjelovic S, Mowen KA. PAD4- mediated neutrophil extracellular trap formation is not required for immunity against influenza infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley SR, Print C, Farahi N, et al. Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1α-dependent NF-κB activity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:105–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyssonaux C, Johnson RS. An unexpected role for hypoxic response: oxygenation and inflammation. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy DA, Watson RWG, Newsholme P. Glucose, but not glutamine, protects against spontaneous and anti-FAS antibody-induced apoptosis in human neutrophils. Clin Sci. 2002;103:179–89. doi: 10.1042/cs1030179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom J, Furst P, Noree LO, Vinnars E. Intracellular free amino acid concentration in human muscle tissue. J Appl Physiol. 1974;36:693–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn KS, Schuhmann K, Stehle P, Darmaun D, Furst P. Determination of glutamine in muscle protein facilitates accurate assessment of proteolysis and de novo synthesis-derived endogenous glutamine production. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:484–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q's next: the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:313–24. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin PJ, Furtak T, Eng K, Gauthier ER. Oxidative stress is not required for the induction of apoptosis upon glutamine starvation of Sp2/0-Ag14 hybridoma cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:355–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuneva M, Zamboni N, Oefner P, Sachidanandam R, Lazebnik Y. Deficiency in glutamine but not glucose induces MYC-dependent apoptosis in human cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:93–105. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeva-Andany M, López-Ojén M, Funcasta-Calderón R, Ameneiros-Rodríguez E, Donapetry-García C, Vila-Altesor M, Rodríguez-Seijas J. Comprehensive review on lactate metabolism in human health. Mitochondrion. 2014;17:76–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts B, Pearce EJ. Metabolic control of dendritic cell activation and function: recent advances and clinical implications. Front Immunol. 2014;5:203. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]