Abstract

CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are required to maintain immunological tolerance; however, defects in specific organ-protective Treg cell functions have not been demonstrated in organ-specific autoimmunity. Non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice spontaneously develop lacrimal and salivary gland autoimmunity and are a well-characterized model of Sjögren syndrome. Lacrimal gland disease in NOD mice is male-specific, but the role of Treg cells in this sex-specificity is not known. This study aimed to determine if male-specific autoimmune dacryoadenitis in the NOD mouse model of Sjögren syndrome is the result of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell dysfunction. An adoptive transfer model of Sjögren syndrome was developed by transferring cells from the lacrimal gland-draining cervical lymph nodes of NOD mice to lymphocyte-deficient NOD-SCID mice. Transfer of bulk cervical lymph node cells modelled the male-specific dacryoadenitis that spontaneously develops in NOD mice. Female to female transfers resulted in dacryoadenitis if the CD4+ CD25+ Treg-enriched population was depleted before transfer; however, male to male transfers resulted in comparable dacryoadenitis regardless of the presence or absence of Treg cells within the donor cell population. Hormone manipulation studies suggested that this Treg cell dysfunction was mediated at least in part by androgens. Surprisingly, male Treg cells were capable of preventing the transfer of dacryoadenitis to female recipients. These data suggest that male-specific factors promote reversible dysfunction of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells and, to our knowledge, form the first evidence for reversible organ-protective Treg cell dysfunction in organ-specific autoimmunity.

Keywords: dacryoadenitis, non-obese diabetic mouse, regulatory T cells, Sjögren syndrome

Introduction

Sjögren syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands followed by exocrine gland dysfunction. Despite being one of the most common autoimmune rheumatic diseases, the pathogenesis of Sjögren syndrome is largely unknown. The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse spontaneously develops lacrimal and salivary gland autoimmunity and is a well-characterized animal model for Sjögren syndrome.1 In this model, only male NOD mice develop spontaneous autoimmune dacryoadenitis, whereas females develop autoimmune sialadenitis.2–5 Androgens have been implicated as the male factor promoting lacrimal gland autoimmunity,5,6 though the mechanisms of immune dysregulation responsible for male-specific autoimmune dacryoadenitis are unknown.

CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are key mediators of peripheral immunological tolerance, and their absence results in profound multisystem autoimmunity in both mice and humans.7 Treg cells are compartmentalized anatomically based on T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire studies such that cells bearing distinct TCRs are concentrated within different groups of organ-draining lymph nodes (LNs).8 The functional consequence of this is believed to be the enrichment of organ-protective Treg cells within organ-draining LNs. In a day 3 thymectomy-induced mouse model of autoimmunity, 15-fold fewer lacrimal gland-draining cervical LN Treg cells were required to prevent dacryoadenitis compared with Treg cells from non-organ-draining LNs.9 Development of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in the day 3 thymectomy model and other Treg-deficient mouse models suggests a role for lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells in preventing lacrimal gland autoimmunity;9,10 however, no defects in organ-protective Treg cells have been identified in spontaneous organ-specific autoimmunity models. In this study, we developed an adoptive transfer model of Sjögren syndrome to determine if lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell dysfunction accounts for the male-specific occurrence of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in NOD mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

NOD, NOD-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), castrated and sham-castrated NOD-SCID mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). NOD mice expressing the bicistronic Foxp3-green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter knocked-in to the endogenous Foxp3 locus were developed by backcrossing Foxp3-GFP knock-in C57BL/6 mice11 for at least nine generations onto the NOD background. Mice were monitored for the presence of glucosuria using Diastix urine dipsticks (Bayer, Whippany, NJ). Mice were maintained and used in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines of the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Iowa.

Antibodies, flow cytometry and cell sorting

Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies used for flow cytometry and/or cell sorting included anti-CD3, CD4, CD25, B220 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and Foxp3 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Intracellular staining for Foxp3 was performed with a Foxp3 staining kit following the manufacturer's protocol (eBioscience). Cells from cervical LNs were analysed by flow cytometry using a BD FACSCanto or BD LSR II for acquisition and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, OR) for analysis. Cells were gated on lymphocytes based on forward scatter and side scatter parameters then on singlets based on forward scatter-area and forward scatter-width before subsequent gates as noted in the figure legends. For FACS, cells were labelled with appropriate combinations of fluorophore-conjugated anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 monoclonal antibodies and the non-Treg population was purified by collecting all non-CD4+ CD25+ cells using a BD FACSAria. For experiments using Foxp3-GFP reporter NOD mice, anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 were used to isolate the Treg-enriched CD4+ CD25+ population and the CD4+ CD25+ cell-depleted non-Treg population, and Foxp3+ Treg cells were further purified from the CD4+ CD25+ population based on GFP expression, with a resulting purity of > 96% CD4+ Foxp3+ cells. For all sorts, purified non-Treg populations contained < 1% CD4+ CD25+ cells and < 2% CD4+ Foxp3+ cells.

Adoptive transfer model of Sjögren syndrome

Donor cells were isolated from cervical LNs pooled from several sex-matched NOD mice and adoptively transferred intravenously to NOD-SCID recipient mice at 5 × 106 bulk cervical LN cells or sorted non-Treg cells per recipient. Some recipients also received CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells co-transferred with the non-Treg cells at physiological ratios based on a pre-sort donor non-Treg : Treg ratio. Donors and recipients were 6–12 weeks old. All donors and recipients tested negative for glucosuria at time of killing for tissue harvesting.

Testosterone treatment

Testosterone-containing pellets (45 mg/pellet, 90-day release) or placebo pellets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) were implanted subcutaneously in the subscapular region of female NOD-SCID mice 1 week before adoptive transfer of donor cells.

Histology and focus scores

Exorbital lacrimal glands were harvested 5–7 weeks after adoptive transfer, fixed in buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Five-micrometre sections of paired glands were stained with haematoxylin & eosin and analysed by standard light microscopy. Inflammation was quantified using standard focus scoring.12 Focus scores (no. of inflammatory foci per 4 mm2) were calculated by a blinded pathologist by counting the total number of foci (composed of ≥ 50 mononuclear cells) by standard light microscopy using a 10 × objective and measuring surface area of sections using Nikon NIS-Elements BR 3.1 software. In some samples, foci were so numerous that they coalesced, preventing accurate enumeration. These samples were designated as diffuse inflammation, and for statistical analyses were assigned focus score values greater than the highest calculable value for that set of comparisons.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism software version 6.02 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Mann–Whitney U-test was used for two-group comparisons of non-parametric data (focus scores). Unpaired Student's t-test was used for two-group comparisons of parametric data (flow cytometry data). P-values < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

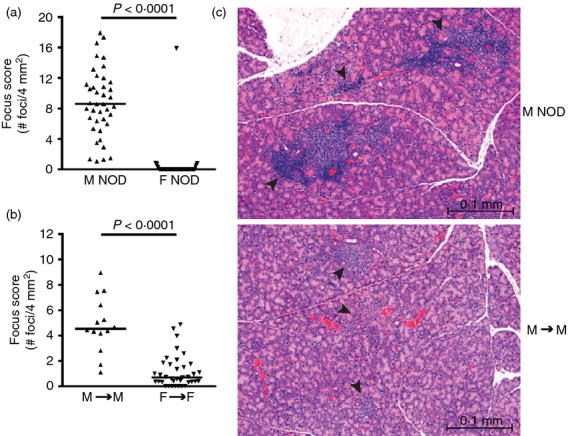

Transfer of bulk cervical LN cells models male-specific autoimmune dacryoadenitis

To study the role of Treg cells in autoimmune dacryoadenitis, we first established an adoptive transfer system that would model the sex-specific autoimmune dacryoadenitis that occurs spontaneously in NOD mice. In this model, bulk cervical LN cells from NOD mice were transferred to lymphocyte-deficient NOD-SCID mice. The use of cervical LNs as the source of donor cells was based on the following: (i) cervical LNs are the organ-draining LNs of lacrimal glands, (ii) organ-protective Treg cells are enriched within the organ-draining LNs,9 (iii) cervical LN Treg cells localize back to the cervical LNs over time following adoptive transfer.13 Similar to spontaneous disease in NOD mice (Fig.1a), development of dacryoadenitis was male-specific with greater inflammation (higher focus scores) in male to male transfers of bulk lacrimal gland-draining cervical LN cells compared with female to female transfers (Fig.1b). We noted the development of increased dacryoadenitis in the female to female transfers (Fig.1b) compared with the non-manipulated female NOD mice (Fig.1a). This may be a result of the transfer into lymphocyte-deficient NOD-SCID hosts, as lymphopenia-induced activation of autoreactive T cells has been described previously.14,15 In males, although the degree of inflammation was greater in non-manipulated NOD males, the inflammatory infiltrates in the recipients of bulk cervical LN cells demonstrated the focal periductal and perivascular mononuclear cell infiltration pattern typical of spontaneous autoimmune dacryoadenitis in both NOD mice (Fig.1c) and human Sjögren syndrome.

Figure 1.

Transfer of non-obese diabetic (NOD) cervical lymph node (LN) cells to NOD-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) recipients models male-specific autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Quantification of inflammation of lacrimal glands from (a) male (n = 40) and female (n = 56) NOD mice; (b) male (n = 14) and female (n = 37) NOD-SCID recipients of sex-matched NOD bulk cervical LN cells, pooled from four or seven transfers, respectively. In (a) and (b), symbols represent individual mice, lines are medians. (c) Representative haematoxylin & eosin-stained lacrimal gland sections from a male NOD mouse (top) and a male NOD-SCID recipient of male bulk cervical LN cells (bottom). Arrowheads indicate mononuclear cell foci in the typical periductal and perivascular distribution. Bars are 0·1 mm. F, female; M, male.

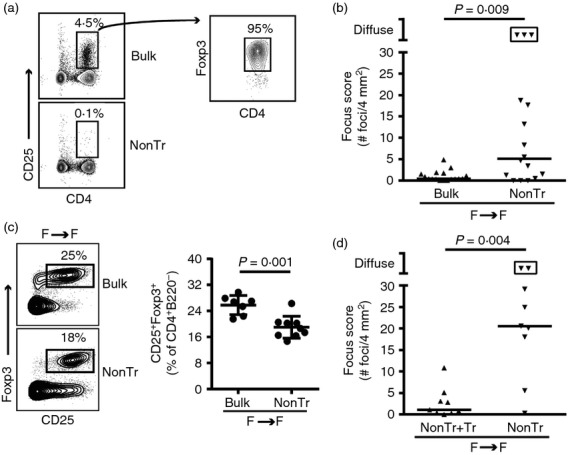

Lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells prevent autoimmune dacryoadenitis in female NOD mice

Having established a transfer system that models spontaneous autoimmune dacryoadenitis in NOD male mice, we considered which cellular populations might be regulating disease. Previous splenocyte-based transfer studies demonstrating the ability of female NOD splenocytes to induce dacryoadenitis in male recipients suggested that female NOD mice have effector cells capable of inducing dacryoadenitis.6 However, the lack of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in non-manipulated female NOD mice (Fig.1a) suggested that these lacrimal gland-specific effector cells were prevented from infiltrating lacrimal glands by some female-specific regulatory mechanism. The development of dacryoadenitis in Treg-deficient mouse models of autoimmunity9,10 suggested that lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells may be required to prevent autoimmune dacryoadenitis. We therefore hypothesized that female NOD mice contain lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells that prevent the spontaneous development of autoimmune dacryoadenitis. To test this hypothesis we compared the transfer of bulk cervical LN cells to the transfer of cervical LN non-Treg cells (i.e. cervical LN cells depleted of the CD4+ CD25+ Treg-enriched population) (Fig.2a) from female NOD donors to female NOD-SCID recipients. Indeed, female recipients of non-Treg cells developed significantly more dacryoadenitis compared with female recipients of bulk cervical LN cells (Fig.2b). Some non-Treg cell recipients developed extensive inflammation in which individual foci coalesced and could not be accurately enumerated.

Figure 2.

Female non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice have lacrimal gland-protective regulatory T (Treg) cells. (a) Representative flow cytometry plots of female bulk cervical lymph node (LN) and non-Treg (nonTr) donor cell populations. Plot on right is gated on CD4+ CD25+ cells. Numbers indicate % of cells within the gate. (b) Quantification of inflammation of lacrimal glands from female NOD-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) recipients of female bulk cervical LN cells (n = 17) or non-Treg cells (nonTr; n = 16), pooled from four transfers. Symbols represent individual mice, lines are medians, boxed symbols represent individual samples with diffuse inflammation such that foci were so numerous they coalesced and could not be accurately enumerated. (c) Representative flow cytometry plots gated on CD4+ B220− singlets from cervical LNs of female NOD-SCID recipients of female bulk cervical LN cells (n = 7) or nonTr (n = 9). Numbers indicate % cells within the gate. Graph depicts cumulative data from recipients pooled from two transfers with symbols representing individual mice, lines representing means, and error bars the SD. (d) Quantification of inflammation of lacrimal glands from female NOD-SCID recipients of female Foxp3-GFP reporter NOD non-Treg cells (nonTr; n = 9) or non-Treg cells plus CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells (nonTr+Tr; n = 9), pooled from two transfers. Symbols, lines and boxed symbols as in (b).

Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ T-cell populations in cervical LNs of recipients at take down 5–7 weeks after transfer (i.e. when lacrimal glands were procured) confirmed decreased CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells within cervical LNs of recipients of non-Treg cells (Fig.2c). CD4+ CD25− Foxp3+ Treg cells were also decreased in recipients of non-Treg cells (not shown). Notably, recipients of non-Treg cells were not completely devoid of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, which may reflect outgrowth of the few (< 1%) CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ cells within the initial donor cell population, proliferation and up-regulation of CD25 by the small proportion of CD4+ CD25− Foxp3+ Treg cells within the initial donor population (approximately 1–2% of donor cells), or conversion of CD4+ Foxp3− non-Treg cells to Foxp3-expressing Treg cells.

To ensure that the increased dacryoadenitis in recipients of non-Treg cells was due to the depletion of the CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cell population, we back-crossed the Foxp3-internal ribosome entry site-GFP reporter construct11 onto the NOD background to generate female mice with heterozygous expression of the reporter knocked-in to the endogenous Foxp3 locus on the X chromosome. We then performed transfers similar to the above in which the CD4+ CD25+ Treg-enriched population was depleted by FACS. We transferred either these non-Treg cells alone or along with the Foxp3+ cells further purified from the depleted CD4+ CD25+ population. Importantly, co-transfer of the Foxp3-expressing CD4+ CD25+ cells along with non-Treg cells from female donors significantly decreased the degree of non-Treg-induced autoimmune dacryoadenitis in female recipients (Fig.2d). Hence, lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells were present within cervical LNs and may prevent the spontaneous development of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in female NOD mice.

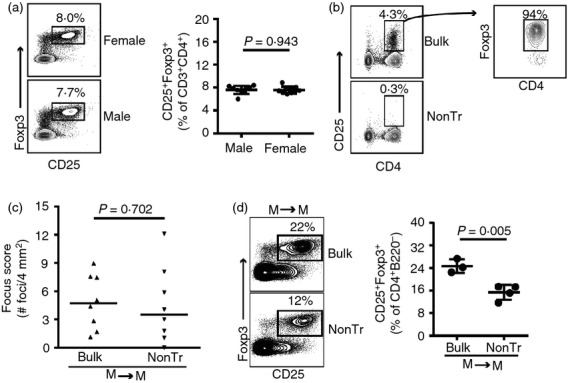

Male NOD mice have defective lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells

Male NOD mice spontaneously develop autoimmune dacryoadenitis (Fig.1a), suggesting that they may have a defect in lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells. However, we found no difference in the proportion of Treg cells within cervical LNs of male and female mice to suggest a sex-specific quantitative Treg cell defect (Fig.3a). To evaluate the functionality of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells within male cervical LNs, we compared the transfer of non-Treg cells to that of bulk cervical LN cells from male donors to male recipients (Fig.3b). These recipients developed comparable dacryoadenitis regardless of the presence or absence of Treg cells in the donor cell populations (Fig.3c). This was not the result of a complete repopulation of Treg cells over time following transfer, as recipients of non-Treg cells had a significantly decreased proportion of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells compared with recipients of bulk cervical LN cells (Fig.3d). This difference was comparable to that of the female to female transfers (Fig.2c). Similarly, decreased CD4+ CD25− Foxp3+ Treg cells were present in cervical LNs of recipients of non-Treg cells (not shown). These data suggest that the spontaneous autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male NOD mice may be the result of defective lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells within cervical LNs.

Figure 3.

Male non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice have defective lacrimal gland-protective regulatory T (Treg) cells. (a) Flow cytometry plots of cervical lymph node (LN) cells from female and male Foxp3-GFP reporter NOD mice, gated on CD3+ CD4+ T cells. Numbers indicate % of cells within the gate. Graph depicts cumulative data from nine males and ten females. (b) Representative flow cytometry plots of male bulk cervical LN and non-Treg (nonTr) donor populations. Plot on right is gated on CD4+ CD25+ cells. Numbers indicate % of cells within the gate. (c) Quantification of inflammation of lacrimal glands from male NOD-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells (n = 8) or non-Treg cells (nonTr; n = 8), pooled from two transfers. (d) Representative flow cytometry plots gated on CD4+ B220− singlets from cervical LNs of male NOD-SCID recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells (n = 3) or non-Treg cells (n = 4). Numbers indicate % cells within the gate. Graph depicts cumulative data from one transfer with symbols representing individual mice, lines representing means, and error bars the SD.

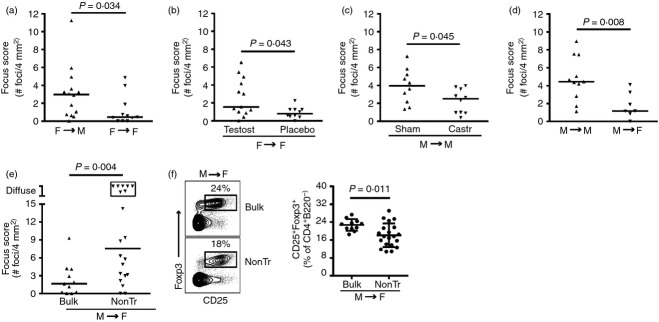

Androgens promote reversible lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell dysfunction

This male-specific, lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell defect may be the result of the absence of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells or to the inability of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells to function in the male host. To evaluate the latter, we next tested whether the lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells within female bulk cervical LNs were capable of preventing autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male recipients. To do this we compared the transfer of bulk cervical LN cells from female NOD donors to male and female NOD-SCID recipients. Male recipients developed significantly more dacryoadenitis than female recipients despite receiving cells from the same donor pool (Fig.4a). This was due at least in part to androgens, as testosterone-treated female NOD-SCID recipients of female bulk cervical LN cells developed significantly more dacryoadenitis than placebo-treated female recipients of cells from the same donor pool (Fig.4b). These data suggest that lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells may not be able to adequately prevent dacryoadenitis in the presence of testosterone.

Figure 4.

Androgens promote reversible lacrimal gland-protective regulatory T (Treg) cell dysfunction. Quantification of inflammation of lacrimal glands from (a) male (n = 14) and female (n = 11) non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD-SCID) recipients of female bulk cervical lymph node (LN) cells, pooled from three or two transfers, respectively; (b) testosterone (testost; n = 13) or placebo (n = 10) -treated female NOD-SCID recipients of female bulk cervical LN cells, pooled from two transfers; (c) sham-castrated (sham; n = 10) or castrated (castr; n = 10) male NOD-SCID recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells, pooled from two transfers; (d) male (n = 11) and female (n = 7) NOD-SCID recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells, pooled from three transfers; (e) female NOD-SCID recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells (n = 11) or non-Treg cells (nonTr; n = 20), pooled from three transfers. Symbols in (a) to (e) represent individual mice, lines are medians. Boxed symbols as defined in Fig.2(b). (f) Representative flow cytometry plots gated on CD4+ B220− singlets from cervical LNs of female NOD-SCID recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells (n = 11) or non-Treg cells (n = 20). Numbers indicate % cells within the gate. Graph depicts cumulative data from three transfers with symbols representing individual mice, lines representing means, and error bars the SD.

Previous studies demonstrated decreased dacryoadenitis in castrated male NOD mice,5,6 though the mechanism of this lacrimal gland protection in the absence of male levels of androgens is not known. We hypothesized that removal of androgens would allow lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells to function. To evaluate this, we first demonstrated that transfer of male bulk cervical LN cells resulted in decreased dacryoadenitis in castrated versus sham-castrated male NOD-SCID mice (Fig.4c). Decreased dacryoadenitis was even more pronounced in female recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells compared with male recipients of the same male donor population (Fig.4d). Hence, in a decreased androgen environment, male bulk cervical LN cells were less effective at inducing dacryoadenitis. To determine if this was indeed due to the presence of functional lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells, we compared the transfer of CD4+ CD25+-depleted non-Treg cells to the transfer of bulk cervical LN cells from male NOD donors to female NOD-SCID recipients. Female recipients of male non-Treg cells developed significantly more dacryoadenitis than recipients of male bulk cervical LN cells, with several recipients of non-Treg cells developing diffuse lacrimal gland inflammation (Fig.4e). Decreased Treg cells (CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ and CD4+ CD25− Foxp3+) within cervical LNs of recipients of non-Treg cells at take down was similar to that of sex-matched non-Treg cell versus bulk cervical LN cell transfers (Fig.4f compared with Figs2c and 3d; and data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate the presence of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells within both male and female cervical LNs that are capable of modulating lacrimal gland autoimmunity in female, but not male, recipients. This suggests that spontaneous lacrimal gland autoimmunity in male NOD mice results from a reversible, lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell defect that may be, at least in part, due to an effect of androgens.

Discussion

Foxp3-expressing Treg cells play a vital role in the maintenance of peripheral immunological self-tolerance. Scurfy mice and children with immune dysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome are Treg deficient as the result of mutations in Foxp3 and develop fatal multi-organ autoimmunity.7,16 Several sets of data suggest that Treg cells function in an organ-specific manner. Studies before the identification of Foxp3 as the key Treg cell transcription factor demonstrated that populations of CD4+ T cells were only capable of preventing experimentally induced autoimmunity in a particular organ if the CD4+ T cells developed in an animal in which the organ of interest was present.17,18 For example, T cells from rats in which thyroid ablation was performed in utero were capable of preventing experimentally induced autoimmune diabetes but did not prevent experimentally induced autoimmune thyroiditis, whereas T cells from rats with intact thyroids were able to prevent both.17 Similarly, CD4+ T cells from male mice, but not female mice or prostate-deficient male mice, were able to prevent experimentally induced autoimmune prostatitis.18 Subsequent studies in experimentally induced autoimmunity models demonstrated that organ-protective Treg cells are enriched within organ-draining LNs.9,19,20 This was demonstrated specifically for experimental autoimmune diabetes,19 autoimmune ovarian disease, experimental autoimmune prostatitis, and experimental autoimmune dacryoadenitis,9,20 the latter three models relying on Treg cell deficiency following day 3 thymectomy for autoimmunity induction. Further evidence for differences in Treg cell specificities within different anatomical compartments came from TCR studies of non-autoimmune-prone mice, which demonstrated that Treg TCR repertoires vary based on the regional LNs from which Treg cells were isolated.8 Together, these studies support a model in which Treg cells are compartmentalized into subsets that protect individual organs, probably because of recognition of organ-specific antigens by the Treg TCR.

If Treg cells function organ/antigen-specifically and are required for the maintenance of immunological self-tolerance, and hence to prevent autoimmunity, then it seems reasonable to expect that organ-specific autoimmunity may be a result of the dysfunction of specific organ-protective Treg cells. However, no previous study has demonstrated such a defect in a spontaneous autoimmunity model or in human autoimmune disease. Studies in humans have been limited to evaluation of peripheral blood Treg cells for global quantitative or in vitro functional defects, and results have been variable.21 Due to the lack of specific markers, such as Treg cell antigen specificity, studies of specific organ-protective Treg subsets in human autoimmunity are not possible. Similarly, lack of identification of Treg cell antigen specificities in animal models also precludes direct evaluation of quantitative defects in specific organ-protective Treg cells in autoimmune disease models. Using an adoptive transfer model based on the transfer of cells isolated from organ-draining LNs, we were able to demonstrate lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells within cervical LNs of both female and male NOD mice; however, these Treg cells were only capable of protecting lacrimal glands (i.e. preventing autoimmune dacryoadenitis) within female recipients (Table1). These data suggest that spontaneous autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male NOD mice is the result of a male-specific, lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell defect driven by a Treg-extrinsic factor. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a specific organ-protective Treg cell defect in a spontaneous autoimmunity model.

Table 1.

Summary of dacryoadenitis in non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD-SCID) recipient mice following transfer of cervical lymph node cells from NOD donor mice

| Donor sex | Recipient | Donor cells | Degree of dacryoadenitis1 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Male | Bulk | ++ | |

| Male | Male | non-Treg cells | ++ | ns2 |

| Male | Sham Male | Bulk | ++ | |

| Male | Castrated Male | Bulk | + | < 0·053 |

| Male | Female | Bulk | + | < 0·012 |

| Male | Female | non-Treg cells | +++ | < 0·0054 |

| Female | Female | Bulk | − | |

| Female | Female | non-Treg cells | +++ | < 0·015, < 0·0056 |

| Female | Female | non-Treg cells + Treg cells | − | |

| Female | Female + Placebo | Bulk | − | |

| Female | Female + Testosterone | Bulk | + | < 0·057 |

| Female | Male | Bulk | + | < 0·055 |

ns, not significant.

Based on median focus scores (no. of foci per 4 mm2) as follows: −, ≤ 1; +, > 1 but < 3; ++ = ≥ 3; +++ = ≥ 3 plus some samples with diffuse inflammation. As a reference, spontaneous dacryoadenitis in NOD mice is ++ for males and − for females.

Compared with Male to Male bulk.

Compared with Male to sham Male bulk.

Compared with Male to Female bulk.

Compared with Female to Female bulk.

Compared with Female to Female non-Treg + Treg cells.

Compared with Female to Female + Placebo bulk.

Previous studies have demonstrated defects in NOD Treg cell numbers and function,22–25 though these have not been universally noted.26,27 Resistance of NOD effector T cells to Treg-cell-mediated suppression has been reported using in vitro studies of polyclonal Treg cell function.24,28,29 How such global defects would result in organ-specific autoimmunity is not entirely clear and would require an additional organ-specific modifying factor. Defects in NOD Treg cell thymic development have also been reported, including decreased diversity of the Treg TCR repertoire,25,30,31 which may lead to holes in antigen-specific Treg populations and subsequent increased susceptibility to organ-specific autoimmunity. Our results do not support a complete lack of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells in male NOD mice given that male cervical LN-derived Treg cells are capable of preventing the transfer of dacryoadenitis to female recipients. Rather, our data demonstrate the presence of both lacrimal gland-specific effector T cells and regulators (i.e. Treg cells) within male and female NOD mouse cervical LNs. Within females, the Treg cells maintain control over the effector T cells, so preventing autoimmune dacryoadenitis (but not other autoimmune manifestations such as autoimmune sialadenitis or diabetes). In males, effector T cells overcome Treg-cell-mediated lacrimal gland protection, resulting in autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Data from this study (Table1) and others5,6 suggest that androgens may play a key role in this male-specific effector/regulator imbalance, though whether androgens disarm functional lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells directly or indirectly through effects on effector T cells, antigen-presenting cells, or target organ epithelial cells remains to be determined.

Treg cells function to suppress autoreactive effector T cells using several mechanisms depending on the context.32 This includes the use of both cell surface proteins and secreted factors to suppress effector T-cell activation and differentiation within secondary lymphoid organs as well as to modulate activated T-cell trafficking to and effector function within non-lymphoid tissues.32–35 The specific mechanisms responsible for Treg-cell-mediated prevention of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in NOD mice and how androgens may alter the Treg cell suppressive programme are not known. Treg cells express androgen receptor (our unpublished observation), and hence studies to define androgen-specific changes in the Treg cell transcriptional programme are warranted. Defining the key molecular mechanisms of Treg-cell-mediated prevention of lacrimal gland autoimmunity in our model may provide insight into the organ selectivity of Treg cell function.

In addition to effects on Treg cells directly, androgens may promote autoimmune dacryoadenitis in NOD mice through effects on effector T cells, which also express androgen receptors.36 Studies in humans and non-autoimmune-prone mice have generally demonstrated immune suppressive effects of androgens including inhibition of CD4+ T-cell differentiation into T helper type 1 or type 17 cells.37,38 Whether an opposite effect promoting an inflammatory immune response occurs in autoimmune prone strains is possible; however, recent studies of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice suggest against a global pro-inflammatory effect of androgens.39–41 On the contrary, these studies demonstrate a protective effect of androgens on the development of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice and suggest a role for gut microbiota in driving this sex specificity. Mechanisms of the hormone–microbe association are complex, including gut microbes promoting increased androgen production39,41 and androgen-mediated alterations in the gut microbiota.40 In both cases, manipulation of the microbiota resulted in modulation of autoimmunity. The specific mechanisms preventing autoimmune diabetes are not entirely clear but may result from microbiota-driven alterations in host metabolism39,41 and/or promotion of tolerogenic macrophages in organ-draining LNs.40 Another NOD mouse study demonstrated the effects of the gut microbiota on host metabolism and autoimmune diabetes development in a sex-independent manner.42 Together these studies highlight a potential key role for gut microbiota, androgens and metabolomics in islet cell autoimmunity in NOD mice. Whether similar or opposite effects occur in lacrimal glands is not known. As androgens promote autoimmune dacryoadenitis (Table1), it will be interesting to determine if manipulation of the gut microbiota results in prevention of autoimmune dacryoadenitis despite resulting in increased androgens.

Ultimately, for any of these mechanisms that exert a global change in immune cell behaviours to result in organ-specific autoimmunity one of the following must be true: (i) mechanisms of Treg-cell-mediated protection differ between organs and are differentially affected by androgens, (ii) androgens alter homing molecule expression (either on T cells or within target organs), or (iii) androgens alter target organ epithelial cells resulting in altered organ-specific antigen expression or otherwise impacting the microenvironment for immune responses, so rendering Treg cells dysfunctional. With regard to (ii) and (iii), the influence of androgens on lacrimal gland gene expression in non-autoimmune-prone mice is well documented,43,44 though whether this differs in autoimmunity-prone NOD mice is not known. Similarly, whether this affects Treg cell homeostasis or function is not known. Intriguingly, a recent study demonstrated that TCR signalling is required for Treg cells to exert suppressive function.45 Using a model in which TCR expression was inducibly ablated in a proportion of Treg cells, the investigators showed that Treg-specific Foxp3 expression and epigenetic changes were largely maintained but that their activated phenotype and ability to prevent autoimmunity in both colitis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis models were severely altered. Survival of the TCR ablated Treg cells decayed slowly over time. Hence, it may be the case that androgens alter the expression of key self-antigens within NOD lacrimal glands, resulting in lack of antigen-specific TCR stimulation of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells within male cervical LNs, rendering them dysfunctional. However, upon transfer to female mice, these lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells would encounter their cognate antigens and become functional. Further understanding the mechanisms of the reversible, male-specific, lacrimal gland-protective Treg cell defect in NOD mice and whether similar defects are responsible for organ-specific autoimmunity in other models may provide for novel therapeutic interventions aimed at re-arming defective organ-protective Treg cells within affected individuals.

In conclusion, we have developed an adoptive transfer model of Sjögren syndrome that results in similar sex specificity of organ involvement that occurs spontaneously in NOD mice. Using this model we identified the presence of lacrimal gland-protective Treg cells in both male and female cervical LNs, which prevent autoimmune dacryoadenitis only in female mice. Although androgens remain a key player in promoting the male-specific autoimmune dacryoadenitis in NOD mice, further characterization of the complex interplay of target tissues and antigen-presenting cells with Treg cells and effector cells is required to fully elucidate the mechanisms of sex-specific immune dysregulation in autoimmune disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Drs Stanley Perlman, Edward Behrens, Martha Jordan and Taku Kambayashi for their critical review of this manuscript; the AFCRI Cell Morphology Core, University of Iowa Histology Research Laboratory, Xiaofang Wang, and Dr David Sullivan for technical assistance; Dr Bonnie Lieberman for helpful suggestions; and Paul Casella for editorial assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- LN

lymph node

- NOD

non-obese diabetic

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Treg

regulatory T

Author contributions

SML performed the experiments and analysed data, PAK analysed histopathology data, SML and GAK designed the study and wrote the paper. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K08 EY022344 to SML, K12 HD043245 which supported SML, and 1S10 RR027219 to the Flow Core facility at the University of Iowa) and by the Arthritis Foundation and the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases, Inc., through an Arthritis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship to SML. Some data presented herein were obtained at the Flow Cytometry Facility, which is a Carver College of Medicine/Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center core research facility at the University of Iowa funded through user fees and the generous financial support of the Carver College of Medicine, Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Iowa City Veteran's Administration Medical Center.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial or commercial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Nguyen CQ, Peck AB. Unraveling the pathophysiology of Sjögren syndrome-associated dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2009;7:11–27. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70289-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda I, Sullivan BD, Rocha EM, Da Silveira LA, Wickham LA, Sullivan DA. Impact of gender on exocrine gland inflammation in mouse models of Sjögren's syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:355–66. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulowska-Mennis A, Xu B, Berberian JM, Michie SA. Lymphocyte migration to inflamed lacrimal glands is mediated by vascular cell adhesion molecule-1/α4β1 integrin, peripheral node addressin/l-selectin, and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 adhesion pathways. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:671–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61738-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunger RE, Muller S, Laissue JA, Hess MW, Carnaud C, Garcia I, Mueller C. Inhibition of submandibular and lacrimal gland infiltration in nonobese diabetic mice by transgenic expression of soluble TNF-receptor p55. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:954–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI118879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Ishimaru N, Yanagi K, Haneji N, Saito I, Hayashi Y. High incidence of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice depending on sex steroid. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:555–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4691368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunger RE, Carnaud C, Vogt I, Mueller C. Male gonadal environment paradoxically promotes dacryoadenitis in nonobese diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1300–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop SK, Santacruz NA, Pham D, Luo J, Hsieh CS. Antigen-specific peripheral shaping of the natural regulatory T cell population. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3105–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler KM, Samy ET, Tung KS. Cutting edge: normal regional lymph node enrichment of antigen-specific regulatory T cells with autoimmune disease-suppressive capacity. J Immunol. 2009;183:7635–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Zheng L, Guo X, Fu SM, Ju ST, Jarjour WN. Novel animal models for Sjögren's syndrome: expression and transfer of salivary gland dysfunction from regulatory T cell-deficient mice. J Autoimmun. 2006;27:289–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarstein K, Wahren M, Zaura E, Hattori M, Jonsson R. Characterization of T cell receptor repertoire and anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies in relation to sialadenitis of NOD mice. Autoimmunity. 1995;22:9–16. doi: 10.3109/08916939508995294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman SM, Kim JS, Corbo-Rodgers E, Kambayashi T, Maltzman JS, Behrens EM, Turka LA. Site-specific accumulation of recently activated CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells following adoptive transfer. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1429–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoruts A, Fraser JM. A causal link between lymphopenia and autoimmunity. Immunol Lett. 2005;98:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Ilic A, Koelsch K, Sarvetnick N. Homeostatic expansion of T cells during immune insufficiency generates autoimmunity. Cell. 2004;117:265–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdell F, Ziegler SF. FOXP3 and scurfy: how it all began. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:343–9. doi: 10.1038/nri3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon B, Mason D. Peripheral autoantigen induces regulatory T cells that prevent autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;189:877–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi O, Kontani K, Ikeda H, Kezuka T, Takeuchi M, Takahashi T, Takahashi T. Tissue-specific suppressor T cells involved in self-tolerance are activated extrathymically by self-antigens. Immunology. 1994;82:365–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EA, Choi Y, Flavell RA. Pancreatic lymph node-derived CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells: highly potent regulators of diabetes that require TRANCE-RANK signals. Immunity. 2002;16:183–91. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samy ET, Parker LA, Sharp CP, Tung KS. Continuous control of autoimmune disease by antigen-dependent polyclonal CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in the regional lymph node. J Exp Med. 2005;202:771–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyara M, Gorochov G, Ehrenstein M, Musset L, Sakaguchi S, Amoura Z. Human FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in systemic autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:744–55. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritt M, Sgouroudis E, d'Hennezel E, Albanese A, Piccirillo CA. Functional waning of naturally occurring CD4+ regulatory T-cells contributes to the onset of autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:113–23. doi: 10.2337/db06-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop SM, Wong CP, Culton DA, Clarke SH, Tisch R. Single cell analysis shows decreasing FoxP3 and TGFβ1 coexpressing CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells during autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1333–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregori S, Giarratana N, Smiroldo S, Adorini L. Dynamics of pathogenic and suppressor T cells in autoimmune diabetes development. J Immunol. 2003;171:4040–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AJ, Hua H, Munson SH, McDevitt HO. Tumor necrosis factor-α regulation of CD4+ CD25+ T cell levels in NOD mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172382999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellanby RJ, Thomas D, Phillips JM, Cooke A. Diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice is not associated with quantitative changes in CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunology. 2007;121:15–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC, Mellanby RJ, Cooke A. Comment on: Tritt et al. (2007) Functional waning of naturally occurring CD4+ regulatory T-cells contributes to the onset of autoimmune diabetes: diabetes 57:113–123, 2007. Diabetes. 2008;57:e6. doi: 10.2337/db06-1700. ; author reply e7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You S, Belghith M, Cobbold S, et al. Autoimmune diabetes onset results from qualitative rather than quantitative age-dependent changes in pathogenic T-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:1415–22. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alise AM, Auyeung V, Feuerer M, Nishio J, Fontenot J, Benoist C, Mathis D. The defect in T-cell regulation in NOD mice is an effect on the T-cell effectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19857–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810713105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira C, Singh Y, Furmanski AL, Wong FS, Garden OA, Dyson J. Non-obese diabetic mice select a low-diversity repertoire of natural regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8320–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808493106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira C, Palmer D, Blake K, Garden OA, Dyson J. Reduced regulatory T cell diversity in NOD mice is linked to early events in the thymus. J Immunol. 2014;192:4145–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz IK, Campbell DJ. Organ-specific and memory treg cells: specificity, development, function, and maintenance. Front Immunol. 2014;5:333. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Kishore M, Gittens B, et al. Self-recognition of the endothelium enables regulatory T-cell trafficking and defines the kinetics of immune regulation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3436. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarween N, Chodos A, Raykundalia C, Khan M, Abbas AK, Walker LS. CD4+ CD25+ cells controlling a pathogenic CD4 response inhibit cytokine differentiation, CXCR-3 expression, and tissue invasion. J Immunol. 2004;173:2942–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoye IS, Coomes SM, Pelly VS, Czieso S, Papayannopoulos V, Tolmachova T, Seabra MC, Wilson MS. MicroRNA-containing T-regulatory-cell-derived exosomes suppress pathogenic T helper 1 cells. Immunity. 2014;41:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten WP, Lieberherr M, Giese G, Wrehlke C, Stamm O, Sekeris CE, Mossmann H, Wunderlich F. Functional testosterone receptors in plasma membranes of T cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:123–33. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissick HT, Sanda MG, Dunn LK, Pellegrini KL, On ST, Noel JK, Arredouani MS. Androgens alter T-cell immunity by inhibiting T-helper 1 differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:9887–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402468111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JJ, Lai KP, Zeng W, Chuang KH, Altuwaijri S, Chang C. Androgen receptor influences on body defense system via modulation of innate and adaptive immune systems: lessons from conditional AR knockout mice. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1504–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science. 2013;339:1084–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1233521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurkovetskiy L, Burrows M, Khan AA, et al. Gender bias in autoimmunity is influenced by microbiota. Immunity. 2013;39:400–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markle JG, Frank DN, Adeli K, von Bergen M, Danska JS. Microbiome manipulation modifies sex-specific risk for autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:485–93. doi: 10.4161/gmic.29795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner TU, Hyotylainen T, Knip M, Backhed F, Oresic M. The gut microbiota modulates glycaemic control and serum metabolite profiles in non-obese diabetic mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e110359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SM, Liu M, Jensen RV, et al. Androgen regulation of gene expression in the mouse lacrimal gland. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;96:401–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DA, Jensen RV, Suzuki T, Richards SM. Do sex steroids exert sex-specific and/or opposite effects on gene expression in lacrimal and meibomian glands? Mol Vis. 2009;15:1553–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahl JC, Drees C, Heger K, et al. Continuous T cell receptor signals maintain a functional regulatory T cell pool. Immunity. 2014;41:722–36. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]