Abstract

AIM: To study the criteria for self-reported dietary fructose intolerance (DFI) and to evaluate subjective global assessment (SGA) as outcome measure.

METHODS: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients were randomized in an open study design with a 2 wk run-in on a habitual IBS diet, followed by 12 wk with/without additional fructose-reduced diet (FRD). Daily registrations of stool frequency and consistency, and symptoms on a visual analog scale (VAS) were performed during the first 4 wk. SGA was used for weekly registrations during the whole study period. Provocation with high-fructose diet was done at the end of the registration period. Fructose breath tests (FBTs) were performed. A total of 182 subjects performed the study according to the protocol (88 FRD, 94 controls).

RESULTS: We propose a new clinically feasible diagnostic standard for self-reported fructose intolerance. The instrument is based on VAS registrations of symptom relief on FRD combined with symptom aggravation upon provocation with fructose-rich diet. Using these criteria 43 of 77 patients (56%) in the present cohort of IBS patients had self-reported DFI. To improve the concept for clinical evaluation, we translated the SGA scale instrument to Norwegian and validated it in the context of the IBS diet regimen. The validation procedures showed a sensitivity, specificity and κ value for SGA detecting the self-reported DFI group by FRD response within the IBS patients of 0.79, 0.75 and 0.53, respectively. Addition of the provocation test yielded values of 0.84, 0.76 and 0.61, respectively. The corresponding validation results for FBT were 0.57, 0.34 and -0.13, respectively.

CONCLUSION: FRD improves symptoms in a subgroup of IBS patients. A diet trial followed by a provocation test evaluated by SGA can identify most responders to FRD.

Keywords: Breath test, Dietary restriction, Fructose malabsorption, Functional bowel disease, Sugar intolerance

Core tip: In this second report from the FINN study, new diagnostic criteria for self-reported fructose intolerance, based on fructose-reduced diet (FRD), were developed. Subjective global assessment of abdominal relief seems to be a valid outcome measure, which may be used as a feasible alternative to daily visual analog scale registrations both in daily routine handling of these patients and in future studies of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). More than half of IBS patients in this study seemed to benefit from using FRD to control their IBS symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

The self-reported intolerance to fructose intake has been described as fructose malabsorption (FM) due to small intestinal dysfunction. This was first reported in four patients with chronic diarrhea and colic in 1978[1], in healthy subjects in 1983[2], and in populations with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in 1986[3]. Fructose is absorbed from the intestinal lumen by facilitated diffusion through the GLUT5 transporter protein in the mucosa, which is a type of glucose-dependent transport[4]. The exact mechanisms leading to incomplete fructose absorption are unknown, and in the literature, they are described as ranging from a true condition to a variance of normality[5]. Moreover, it is well established that factors such as dietary sorbitol[6,7] and dietary non-hydrolysable fructans[8] aggravate IBS symptoms[9]. The amount of sorbitol needed to provoke IBS symptoms appears to be ≥ 10 g[10].

The current diagnostic test for FM, the fructose breath test (FBT), is suboptimal due to the many variations in the normal capacity of fructose absorption[5]. There are numerous factors that give false-negative and false-positive results, as reviewed by Kyaw and Mayberry[5]. These include factors such as colonization by non-hydrogen-producing bacteria and gastrointestinal dysmotility[5]. In a recently published report we have described a discrepancy between the FBT and the effects of a fructose-reduced diet (FRD)[11].

Due to the lack of an accurate and valid test for diagnosing FM, there is an increasing interest to use self-reported responses to FRD as a diagnostic tool for FM. Goldstein et al[6] reported that in patients with IBS or functional abdominal complaints, 56%-60% improved their symptoms when on a low-fructose diet; a finding also reported in some observational studies[12-14]. Therefore, as advocated by Fernández-Bañares et al[14], the use of FRD is a simple and feasible test that should be utilized more in clinical practice. So far, there is no standardized procedure for performing FRD tests. This includes no standardized level for the upper load of fructose to be used per meal, as well as a lack of a clinical tool to assess the effects of FRD in IBS patients.

The aims of the present study were: (1) to define criteria for self-reported dietary fructose intolerance (DFI) in a cohort of patients with IBS defined by Rome II criteria; and (2) to evaluate subjective global assessment (SGA) registration as an alternative to a diary-based symptom registration (VAS scale) as an outcome measure. This is a follow-up report of the open multicenter randomized controlled trial, Fructose Malabsorption in Northern Norway[11].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enrolment and patient flow

The study outline has been published earlier[11]. In brief, during the period July 2008 and July 2011, patients who met the Rome II criteria for diagnosis were recruited. The IBS patients were registered according to their subtypes: constipation or diarrhea. An individual diagnostic workup was performed including, but not mandatory, blood tests, stool samples, breath tests, endoscopy and histological examination, and X-ray or ultrasound investigations to ensure the exclusion of organic disease or other malabsorption diseases such as lactose intolerance or celiac disease. Exclusion criteria were patients with severe chronic disease, severe chronic constipation (defined as laxative users), patients taking antibiotics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and patients whom had previously had performed an FBT or used an FRD.

Study design

As previously described[11], the study was designed with a pre-registration period of 2 wk in which the patients followed their individual habitual IBS diet (HID). The patients were then randomized without stratification to continue HID with or without additional FRD (< 2 g fructose per meal) for 12 wk.

The randomization was assisted by The Scientific Department, University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø.

Individual instructions for the FRD were given both verbally and through written information that included a table in Norwegian showing the fructose content in 91 common food ingredients (a similar table can be found at web site given in reference 15). For a short version of the table of instructions see Table 1.

Table 1.

Fructose-reduced diet (according to definition < 2 g fructose/meal)

| Food item | In moderation | Use sparingly | Avoid |

| Fruit/berries | Lemon, raspberries, blueberries | All other types of fruit and berries | |

| Vegetables | Most vegetables, avocado | Tomato purée | Carrots, legumes, boiled potatoes |

| Meat/fish/eggs | 100% ground beef and fish with no additives | Caviar, mackerel in tomato sauce | |

| Anchovies and herring | |||

| Milk products | White/brown cheeses/cream and sour cream | Cheeses with fruit added | Fruit yoghurt, ice cream and puddings |

| Grain products | Bread, pasta, rice and white flour | Sweet bakery and cereals | |

| Miscellaneous | Margarine, oils, mayonnaise, nuts | Dressings, ketchup | Sweets, chocolates |

| Drinks | Water, milk, tea, coffee, light soda and light fructose drinks | Light orange juice | Juice, nectar, sodas and fructose drinks, milk with sugar or fructose added |

In addition to daily VAS registrations of abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, stool frequency and consistency for 4 wk, an SGA registration was completed once weekly for 12 wk. Early dropouts (defined as patients who registered for < 3 wk of the main 12-wk period) were replaced but late dropouts were not replaced. Data from patients that registered for > 3 of the 4 wk were included in the total registration. The main reason for choosing a 4-wk VAS registration was concern about compliance because the subject would have to perform daily registrations throughout the study. After the main registration period, the patients delivered their diaries, underwent FBT, and were instructed in the fructose-rich provocation test for a maximum of 7 d, or for a shorter time if the test provoked IBS symptoms. For the provocation test, patients were told to choose sucrose-rich food and to include ≥ 200 mL of fruit juice with only small amounts of sorbitol in each daily meal[15,16] (e.g., 200 mL orange juice, 8-9 g fructose with no sorbitol content/200 mL apple juice, 15 g fructose and 1 g sorbitol). Study patients were instructed to use the same information table as a guide for both reducing fructose load and ensuring a sufficient intake of fructose (30 g) during the provocation test[15]. The VAS and SGA scores (as compared to the last week of main registration)[11] were logged in a separate provocation diary.

Symptom score of IBS

The subjects filled in a symptom registration diary. Each day they marked on a VAS form (0-100 mm) the degree of pain and bloating experienced (0 mm for no symptoms, and 100 mm for maximal symptom score). In addition, they counted the number of stools and gave a description of the stool quality on a scale of 1-7 (Bristol scale)[13].

Self reported fructose intolerance: Diagnostic criteria

Based on the experiences from our first study[11], a diagnostic test based on a self-reported (subjective) intolerance to fructose in IBS was constructed. We defined fructose-related food intolerance as a combination of symptom relief associated with dietary fructose restriction and symptom exacerbation following a fructose provocation test. In our previous study[11] the Bland-Altman analysis showed that the technical detection limits (corresponding to 1.96 SD of mean bias) were 18 mm (18% on VAS scale of 100 mm) for pain/discomfort and 17 mm for bloating. Based on these boundaries a response to FRD was defined as > 25 mm relief, whereas > 25 mm worsening of the VAS score during provocation was considered a positive test[11].

SGA score of IBS

Patients determined the SGA of abdominal relief once during every weekend of the study period by entering their assessment in their personal diary. The assessment was completed by answering the following question: Please consider how you have felt the past week with regards to your IBS, in particular your overall wellbeing, symptoms of abdominal discomfort, pain and altered bowel habit compared to how you felt before entering the study). How do you rate your relief (or worsening) of symptoms during the past week? The scale contained five possible answers: (1) completely relieved; (2) considerably relieved; (3) somewhat relieved; (4) unchanged; or (5) worse[17]. Using the SGA score, patients who were somewhat relieved in week 3 and 4, or completely/considerably relieved in at least 1 wk were considered to have responded to the FRD.

Breath tests

Hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) were measured by a Microlyzer (Quintron Instrument Co. Inc., Milwaukee, WI, United States) in end-expiratory breath samples. After an overnight fast, H2 and CH4 levels were measured before drinking 15 mL solution corresponding to 50 g fructose). Measurements were performed every 30 min until a gas peak was reached, or up to 4 h. A high load of fructose was used to minimize false-negative results as indicated by Choi et al[12]. Incomplete absorption was defined as an increase of H2 > 20 ppm or CH4 > 12 ppm, or a sum of combined peak increase > 15 ppm. Symptoms during and after the test were recorded.

Statistical analysis and validation

The statistical analysis included all randomized patients (intention to treat). Patients where split into the two predefined groups according to the study protocol; either a normal IBS diet alone or combined with FRD. A test-retest analysis of SGA was performed by comparing scores at pre-registration with those at 1, 4 and 12 wk in the control group; ∆ values were run using a Wilcoxon signed rank test vs 0. Internal consistency was explored by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Spearman’s correlation on ∆VAS (week 0 vs week 4) vs SGA score at 4 wk in all included patients. The former analysis also yielded information regarding scale linearity and precision of the SGA measure. Finally, the face validity denoting whether the questions made sense was performed in all of the patients and 10 healthy volunteers.

RESULTS

Enrollment of patients

Patient inclusion in this multicenter study is described in detail in a previous publication[11]. In brief, 310 patients admitted to hospital with IBS symptoms were screened, and 108 did not meet the inclusion criteria. The 202 patients included were randomized, and 182 completed the main registration period of 12 wk. All early dropouts were replaced. All patients reported a combination of constipation and diarrhea. A total of 88 patients were randomized to FRD. Among these, we experienced missing data from 11 patients; nine due to a missing provocation diary and two that missed markings for SGA change in week 4 of the main diary. The remaining 77 patients reported complete VAS and SGA data both during the pre- and main registration periods, as well as a complete registration during the provocation test. We found no significant differences in age, sex ratio, abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, stool frequency or Bristol scale stool consistency between the FRD + HID and HID groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and baseline variables for patients included

| All (77) | SRFI neg. (34) | SRFI pos. (43) | P value | |

| Age, yr (median range) | 43 (18-73) | 46 (19-73) | 43 (18-73) | NS1 |

| Female/male ratio (%) | 61/16 | 25/9 | 36/7 | NS2 |

| Abdominal pain/discomfort (mm) | 53(3-89) | 58 (3 89) | 50 (16-76) | NS1 |

| Bloating (mm) | 55 (20-84) | 58 (22-83) | 54 (20-84) | NS1 |

| Stool frequency [median (range)] | 1.5 (0-4) | 1.6 (1-4) | 1.5 (0-4) | NS3 |

| Boston scale stool consistency | 4.4 (1.9-6.0) | 4.6 (1.9-6.0) | 4.3 (2.6-5.9) | NS1 |

Independent samples t-test;

The χ2 test;

Mann-Whitney U. IBS: Measures are mean preregistration values (95%CI) unless otherwise stated. Treatment group differences were tested. SRFI: Self reported fructose intolerance; NS: Not significant.

Validation analysis of SGA

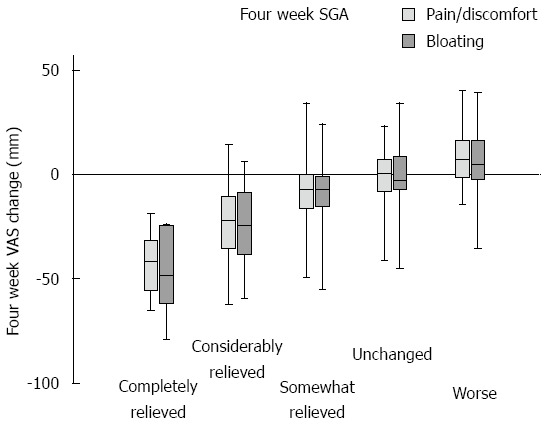

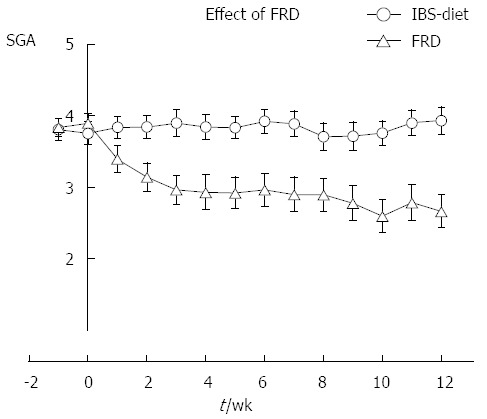

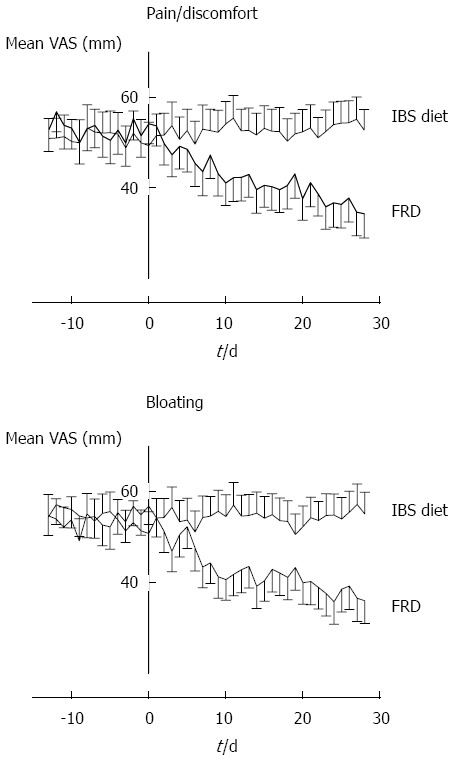

Internal consistency was tested by calculating the VAS change for each of the 182 patients by comparing status at 4 wk with pre-registration. These ∆ values were compared to SGA scores at week 4 using the Spearman Rank correlation test. The analysis yielded ρ values of 0.59 (SGA vs pain/discomfort, P < 0.0005); 0.58 (SGA vs bloating, P < 0.0005); and 0.84 (bloating vs pain/discomfort, P < 0.0005). The graph for the control group illustrated in Figure 1 shows that SGA is a stable measure throughout the 3-mo study period. A test-retest analysis was performed by analyzing the control group SGA values in pairs. For each record, the differences between pre-registration week 0 and weeks 1, 4 and 12 were calculated. These delta values were analyzed with a Wilcoxon signed rank test using zero as the median for the null-hypothesis. The three ∆ values were not significantly different from zero (P = 0.41, 0.13, and 0.42 for pre-registration vs week 1, 4, and 12, respectively). Figure 1 shows the raw data distribution of VAS change registrations in the five SGA categories at 4 wk for all 182 study participants. The SGA scale is not linear; it discriminates best between the span of somewhat relieved and towards completely relieved. Two-way ANOVA of this dataset (VAS by SGA × Diet group) was performed and pairwise comparison is presented in Table 3. The traces for the control group in Figures 2 and 3 show that the VAS measure and the SGA rating were stable over time when used in an IBS setting.

Figure 1.

Scale and precision of the subjective global assessment measure. At 4 wk, the change in VAS registration (compared to pre-registration values) was calculated. Box and whiskers plot of VAS change in the different subcategories of SGA at 4 wk. It is noted that the scale is not entirely linear, with best discrimination in the left part of the plot, while the right part shows smaller VAS differences between groups. SGA: Subjective global assessment; VAS: Visual analog scale.

Table 3.

Pairwise comparisons of visual analog scale readings by ANOVA

| SGA week 4 | Model: F = 30.5; P < 0.0005 | VAS difference, mean ± SE | P value | SGA week 4 | Model: F = 32.6; P < 0.0005 | VAS difference, mean ± SE | P value |

| VAS bloating | Adj R2 = 0.47 | VAS pain/discomfort | Adj R2 = 0.46 | ||||

| Unchanged vs | Completely relieved | 46.1 ± 6.1 | < 0.0005 | Unchanged vs | Completely relieved | 41.1 ± 5.5 | < 0.0005 |

| Considerably relieved | 23.5 ± 3.0 | < 0.0005 | Considerably relieved | 20.8 ± 2.7 | < 0.0005 | ||

| Somewhat relieved | 7.6 ± 2.8 | 0.066 | Somewhat relieved | 5.9 ± 2.5 | 0.202 | ||

| Worse | -7.4 ± 3.3 | 0.275 | Worse | -9.4 ± 3.0 | 0.024 |

Results for two-way ANOVA: VAS by SGA × Diet. Mean differences in VAS change of SGA categories compared to unchanged, adjusted for diet type. P values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction. SGA: Subjective global assessment; VAS: Visual analog scale.

Figure 2.

Subjective global assessment of irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms during the whole study. Mean registration (95%CI) for study groups. The control group showed stable mean value during the 2 + 12 wk registration. The mean effect of FRD was marked, showing stable improvement of symptom rating during the whole study. The SGA ratings were: 1: Completely relieved; 2: Considerably relived; 3: Somewhat relieved; 4: Unchanged; 5: Worse. FRD: Fructose-reduced diet; SGA: Subjective global assessment; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome.

Figure 3.

Visual analog scale registrations of irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms during the first 2 + 4 wk. Mean registration (95%CI) for the study groups. FRD: Fructose-reduced diet; VAS: Visual analog scale; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome.

As shown in Table 4, for SGA, there was good sensitivity and specificity of 0.84 and 0.74, respectively, for identifying self-reported DFI. The inclusion of a provocation test in the diagnostic criteria improved the quality of the test criteria; especially the negative predictive value (Table 4). The sensitivity and specificity parameters for the FBT were low (Table 4).

Table 4.

Testing new diagnostic criteria of self-reported fructose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome (for definition, see text) against fructose breath test and response of subjective global assessment test

| Predictive | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Kappa |

| FBT | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.29 | -0.13 |

| SGA weeks 3-41 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.53 |

| SGA week 3-42 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.61 |

Without result provocation;

With result provocation. SGA: Subjective global assessment; FBT: Fructose breath test.

Self-reported DFI: Agreement with breath tests

Using our new criteria for the diagnosis of self-reported DFI, we established a diagnostic tool for fructose intolerance based on the results from the agreement testing (frequency analysis) (Table 4). As described in our earlier report[11], a discrepancy was found between the self-reported fructose intolerance and FBT. This was confirmed in the frequency analysis that gave a κ value of -0.13. There was a good agreement between the diagnosis of self-reported DFI and the SGA responses to FRD according to the criteria used (see methods) with a κ value of 0.61 (Table 4). When results from the provocation test were excluded from the diagnostic criteria, the κ value was less precise (κ = 0.53).

Prevalence of self-reported fructose intolerance

The prevalence of self-reported fructose intolerance, defined as a combination of response to FRD and a positive provocation test, was 56% (43 of 77 patients).

DISCUSSION

In this open label, unstratified, randomized multicenter study of FRD in patients with IBS, we proposed new diagnostic criteria for FM based on the combination of effects from FRD and a positive provocation test. This is based on symptom registration (using a VAS scale) as the outcome measure. The FBT shows poor characteristics for identifying these patients. An alternative SGA registration, as an outcome measure for FRD, showed a good agreement with the new diagnostic criteria. Our study opens a new approach in the management of DFI in IBS patients. A fructose-restricted diet of < 2 g fructose per meal, together with a standardized method for SGA registration, can be used as the first step in the management of IBS patients in clinical practice. Using these new diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of self-reported fructose intolerance in the IBS cohort admitted to a gastroenterology unit was as high as 56%.

In this study, the criteria for the diagnosis of fructose intolerance are based on self-reported symptoms of relief, whilst on FRD, and symptom aggravation following a fructose provocation test.

This was chosen due to the lack of a more precise or accurate objective test, including breath tests[5]. The international consensus of nomenclature for food-related disorders from 2001[18] defines self-reported fructose intolerance as a nonallergic hypersensitive reaction to fructose-rich food items. Moreover, the concept of self reporting is a descriptive term based on patient registration of symptoms[19]. In other reports of food-related disorders in which objective diagnostic tests were lacking, the patient’s symptoms were referred to as subjective[20] or perceived[21].

In this study, we used SGA as a clinical tool to assess the effects of FRD. A translated modification of a 5-degree scoring system of a validated questionnaire for IBS, described by Müller-Lissner et al[17], was performed. The validation of the Norwegian translation of SGA, used in IBS patients on an FRD, showed good agreement with VAS measures - and in particular, the categories completely relieved and considerably relieved indicated a substantial change in VAS recordings. The scale is not linear, and the VAS recordings do not as clearly differentiate between the category transitions somewhat relieved-unchanged and unchanged-worse.

Considering our earlier study on VAS recordings for this patient group, these transitions represent VAS differences that are lower than the technical discrimination limits of 17 and 18 mm for bloating and pain/discomfort, respectively[11]. In contrast, the categories completely relieved and considerably relieved both represent a mean VAS change above the technical discrimination limit. Thus, a single SGA rating should reliably identify an improvement in symptoms when rated as completely relieved or considerably relieved. The test-retest analysis showed no significant time-related bias, which was also demonstrated in the graph for the control group in Figure 3. Face validity was evaluated in healthy volunteers, and revealed no problems in the interpretation of the questions. Finally, good sensitivity and specificity for identifying self-reported DFI was found for SGA.

According to the proposed diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of self-reported fructose intolerance in a cohort of IBS patients admitted to a gastrointestinal unit was 56%. Among the few studies reporting the prevalence of FM, defined according to FBT, Goldstein et al[6] reported that 44% of patients with IBS or functional abdominal complaints had the condition.

This was based on a consumption of 50 g fructose and 56%-60% improved on a low-fructose diet[6], whereas Barrett et al[22] found FM as high as 34% in healthy volunteers. Finally, in the recently published FODMAP diet studies, representing a diet reduced in fructose and other carbohydrate types, about 50% of the IBS patients improved their symptoms and VAS scores[23]. Our prevalence data must be interpreted with some caution. Including only those who reported complete relief of their symptoms by FRD, the prevalence was reduced to about 20%. Moreover, based on the individual normal variation for the capacity of fructose absorption[5], the prevalence of self-reported fructose intolerance in IBS has to be compared with the reference population, including potential factors such as genetics and the fructose content in daily food intake.

The strength of this study was that we performed a prospective randomized study with validation of the SGA as a tool for assessing IBS-related symptoms during dietary treatment. The FBT was performed after 12 wk observation, which prevented potential bias during registration of symptoms.

There were some limitations to the study. First, the intervention could not be blinded for obvious reasons. Second, a more exact diary registration of the amount of fructose, glucose, and sorbitol intake in each meal during the FRD[7], could have given valuable information. Finally, based on our knowledge of normal variations with regards to fructose absorption capacity[5], a more detailed background registration of the fructose/sucrose content in the daily food intake of the IBS patients and in the reference population would have given more comprehensive data.

A substantial increase in the prevalence of IBS has been observed in the past 20 years. During the same period, consumption of fructose as well as processed food and additives has increased in the general population[24]. It is tempting to speculate that the increased fructose ingestion may explain the observed increase in IBS. If so, an FRD could be an appropriate option for diagnosis and treatment of patients with IBS. If this diet induces symptom relief, according to SGA registrations, a subsequent simple provocation test, two glasses of fruit juice with low sorbitol content at each meal, in combination with an augmented intake of fructose-rich food, could be performed.

New diagnostic criteria for self-reported fructose intolerance, based on FRD are proposed. SGA appears to be a valid outcome measure, which is a feasible alternative to daily VAS registrations; both in daily routine management of these patients and for future studies of IBS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the research nurses Odd Sverre Moen Gastro lab, UNN for technical assistance, dietician Marit Marthinussen Hospital of Helgeland helped with the planning of the FRD, and our colleagues at the gastroenterology departments for help with recruiting patients.

COMMENTS

Background

A substantial increase in the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has been observed in the past 20 years. The main symptoms of IBS include abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea or constipation. During the same period, an increase in the consumption of fructose, as well as processed food and additives has been seen in the general population. Fructose intolerance is regarded as a subgroup of IBS, and it has been proposed that the increase in IBS actually represents fructose intolerance as a result of the increased intake of this sugar. In the recently published FODMAP diet studies, which consist of a diet reduced in fructose and other carbohydrate types, about 50% of the IBS patients are reported to improve their symptoms and visual analog scale (VAS) score.

Research frontier

The self-reported intolerance to fructose intake has been described as fructose malabsorption (FM) due to small intestinal dysfunction. This was first reported in four patients with chronic diarrhea and colic in 1978. Despite later extensive studies the mechanisms behind this disease or medical condition are still unknown. One of the main unresolved problems is whether fructose intolerance is due to an overload of fructose intake and/or a defect in fructose absorption from the intestinal lumen.

Innovation and breakthroughs

Last year the authors published a report from the study Fructose malabsorption in Northern Norway (FINN study) in which the fructose breath test - the only objective test of FM - correlated poorly with self-reported fructose intolerance among IBS patients. In this second report from the FINN study, Subjective Global assessment of abdominal relief (subjective global assessment) was shown to be a valid end-point measure. This report also shows that a high dietary fructose load is the main explanation for this disease.

Applications

Validated end-point measures are necessary tools for future studies of self-reported fructose intolerance.

Terminology

Fructose intolerance is defined as a self-reported intolerance to a normal load of fructose intake. FM is a similar concept, but mainly based on the abnormal intestinal absorption of fructose measured by FBT. The two concepts are used interchangeably in the literature and most likely describe the same medical condition.

Peer-review

Although the findings of this study replicate commonsense practice, this is a useful addition to literature in these days of evidence-based medicine. The sequence the authors followed is historically what happened with the lactose-intolerance studies, where the focus shifted from mucosal lactase measurements to lactose tolerance curves to symptom analysis

Footnotes

Supported by Northern Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Nord RHF); Gastro Fund, University Hospital North Norway; and Helgeland Hospitals Research Committee.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed and approved by Helse Nord RHF Institutional Review Board and approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of Northern Norway.

Clinical trial registration: The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00555191).

Informed consent: All study participants provided written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data sharing: The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Rasmus Goll from University Hospital of Northern Norway and University of Tromsø. Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from corresponding author at leif.kyrre.berg@online.no.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: October 31, 2014

First decision: November 26, 2014

Article in press: January 30, 2015

P- Reviewer: Abraham P S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Andersson DE, Nygren A. Four cases of long-standing diarrhoea and colic pains cured by fructose-free diet--a pathogenetic discussion. Acta Med Scand. 1978;203:87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1978.tb14836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravich WJ, Bayless TM, Thomas M. Fructose: incomplete intestinal absorption in humans. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Høyer E. Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults. Comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides. Gut. 1986;27:1161–1168. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.10.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones HF, Butler RN, Brooks DA. Intestinal fructose transport and malabsorption in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G202–G206. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00457.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyaw MH, Mayberry JF. Fructose malabsorption: true condition or a variance from normality. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:16–21. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181eed6bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein R, Braverman D, Stankiewicz H. Carbohydrate malabsorption and the effect of dietary restriction on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and functional bowel complaints. Isr Med Assoc J. 2000;2:583–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symons P, Jones MP, Kellow JE. Symptom provocation in irritable bowel syndrome. Effects of differing doses of fructose-sorbitol. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:940–944. doi: 10.3109/00365529209000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson PR, Newnham E, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG. Review article: fructose malabsorption and the bigger picture. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:349–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedewa A, Rao SS. Dietary fructose intolerance, fructan intolerance and FODMAPs. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16:370. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyams JS. Sorbitol intolerance: an unappreciated cause of functional gastrointestinal complaints. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg LK, Fagerli E, Martinussen M, Myhre AO, Florholmen J, Goll R. Effect of fructose-reduced diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, and its correlation to a standard fructose breath test. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:936–943. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.812139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi YK, Kraft N, Zimmerman B, Jackson M, Rao SS. Fructose intolerance in IBS and utility of fructose-restricted diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:233–238. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802cbc2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johlin FC, Panther M, Kraft N. Dietary fructose intolerance: diet modification can impact self-rated health and symptom control. Nutr Clin Care. 2004;7:92–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández-Bañares F. Reliability of symptom analysis during carbohydrate hydrogen-breath tests. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:494–498. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328356689a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Bañares F NUTTAB. NUTTAB 2010 Online Searchable Database. Available from: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/nutrientables/nuttab/Pages/default.aspx.

- 16.Fernández-Bañares F Nutritiondata. SELFNutritionData. Available from: http://nutritiondata.self.com/foods.

- 17.Müller-Lissner S, Koch G, Talley NJ, Drossman D, Rueegg P, Dunger-Baldauf C, Lefkowitz M. Subject’s Global Assessment of Relief: an appropriate method to assess the impact of treatment on irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms in clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:310–316. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Dreborg S, Haahtela T, Kowalski ML, Mygind N, Ring J, van Cauwenberge P, et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy. An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001;56:813–824. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.t01-1-00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lind R, Berstad A, Hatlebakk J, Valeur J. Chronic fatigue in patients with unexplained self-reported food hypersensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome: validation of a Norwegian translation of the Fatigue Impact Scale. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:101–107. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S45760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morken MH, Lind RA, Valeur J, Wilhelmsen I, Berstad A. Subjective health complaints and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome following Giardia lamblia infection: a case control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:308–313. doi: 10.1080/00365520802588091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lied GA. Indication of immune activation in patients with perceived food hypersensitivity. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett JS, Irving PM, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Comparison of the prevalence of fructose and lactose malabsorption across chronic intestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantor LS. A dietary assessment of the US food supply. Washington, DC: Agricultural Economic Report. No. 772. US Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]